Abstract

In this report we present a study of a series of Re(CO)3 pyridineimine complexes with pendant phenol groups. We investigated the effects of the position of the phenol hydroxyl group (para, meta or ortho to the imine) on the steric and electronic characteristics of a series of Re(CO)3X(pyca-C6H4OH) compounds, where X = Cl, Br and pyca = pyridine-2-carbaldehyde imine. These compounds can be generated either via ligand synthesis followed by metal chelation (compound 4) or via a one-pot method (compounds 2, 3, 5 and 6). All six compounds show striking differences in pH-dependent UV-visible absorption based on the position of the phenol hydroxyl group.

Introduction

Recent years has seen a new-found interest in the chemistry of the d6 Re(CO)3 core, notable for the fact that so many of its derivatives are water and air stable. Re(CO)3 complexes have been investigated as models for 99mTc(CO)3 radiopharmacuetical imaging agents as well as for therapeutic agents using the β−-emitting nuclides 186Re and 188Re.1–3 They have also been investigated as components of optical materials, in particular when the Re(CO)3 moiety is bound by a diimine. The Re(diimine)(CO)3 compounds exhibit metal-to- ligand charge transfer transitions, and are of interest due to their novel photophysical properties.4 Accordingly, these compounds have been investigated as electron transfer dyes in proteins5, in nonlinear optical (NLO)6 materials, for solar energy conversion7 and as chemical or biological sensors.5 Compounds containing the photoluminescent Re(CO)3 core have been utilized useful for imaging applications as demonstrated in various studies.8–11

Several years ago, Heinze and coworkers12, 13 have observed that some rhenium, platinum and palladium complexes bearing diimine ligands with an acidic phenol group exhibit pH-sensitive behavior at room temperature. Upon deprotonation, these compounds undergo significant changes to their UV-visible spectra, and in particular Re(CO)3Cl(pyca-C6H4-p-OH) (pyca = pyridine-2-carbaldehyde imine) shows intense absorptions above 550 nm upon loss of the phenol proton. We have been working on similar compounds incorporating the pyca ligand, and have synthesized a variety of related compounds as part of our investigations into the biologically relevant chemistry of M(CO)3, M = 99mTc(I)/Re(I).14, 15 We observed that in many cases these compounds can be produced via a one-pot reaction, with Schiff base formation taking place at the metal ion.16

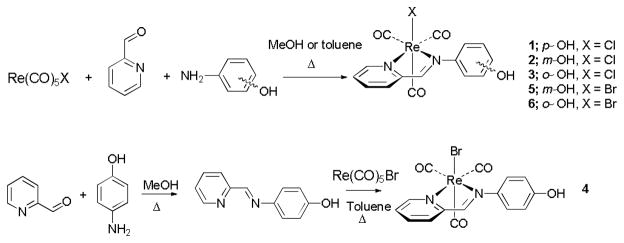

We decided to investigate how the identity of the halide and the position of the phenol group would affect the pH-dependent UV-visible absorption properties of pycaphenol Re(CO)3 compounds. Herein, we describe the reactions of Re(CO)5X (X = Cl or Br) with pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde and ortho-, meta- or para-aminophenol, affording a series of Re(CO)3X(pyca-C6H4OH) compounds (1–6). The syntheses of these compounds are shown in Scheme 1. In addition to using the known method of generating the ligand prior to metal coordination, we were able to apply one-pot methods for the synthesis of most of the desired compounds. We observed that the relative position of the hydroxide does affect the pH-dependent UV-Visible properties of the resultant complexes, but that the halide identity does not have an effect. We have structurally characterized all new compounds, and were able to compare structural parameters with the observed pH-dependent spectroscopic changes.

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of 1–6.

Results and discussion

Syntheses of 1–6

The synthesis of compound 1 by refluxing the premade diimine ligand in the presence of Re(CO)5 Cl has been reported previously, by Liu and Heinze.13 We have prepared compound 1 along with 2, 3, 5 and 6 using one-pot reactions as shown in Scheme 1. Re(CO)5Cl, pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde and the amino phenol were reacted at reflux in methanol or toluene for several hours. Compounds 1–3 were prepared after four hours of reaction in methanol. Compounds 5 and 6 were synthesized via a one-pot reaction in refluxing toluene for 12 hours, upon which the products precipitated from solution. Complex 4 was produced in a stepwise manner by the synthesis of the diimine ligand followed by addition of Re(CO)5Br. All compounds were isolated as pure compounds in good yield.

Spectroscopic characterization

Infrared spectra for each compound showed carbonyl peaks between 2030–1860 cm−1, typical of a pseudo-C3v symmetry resulting from a facial arrangement of carbonyls. A phenolic OH stretches were observed between 3200–3400 cm−1. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra for 1–6 were as expected with diagnostic peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum at ~10.00–10.15 ppm for the phenolic protons, at ~9.2–9.3 ppm for the imine protons, and in the 13C NMR spectrum at 168–172 ppm for the exocyclic imine carbons.

X-ray data collection and structure determination

We were able to structurally characterize compounds 2–6, and compare them to the structure previously reported for 1.13 The structures of compounds 2–6 are shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 lists data collection and structural parameters for compounds 2–6; key bond lengths and angles for these complexes are shown in Table 2. Including the known structure of 1, all six complexes adopt slightly distorted octahedral geometries with the three carbonyls ligands occupying a facial geometry. The diimine ligand binds to the rhenium atom in a bidentate fashion via the two nitrogen atoms, forming a five-member metallocycle. All N1-Re1-N2 bite angles are ~74–75º and are similar to those of previously reported metal complexes with pyridine imine ligands.17 The C-O bonds lengths are normal for Re(CO)3+ species (~1.14–1.16 Å).18 The Re-C bond lengths are in agreement with typical ranges (~1.87–1.95 Å), and the Re-X (Cl or Br) bond lengths are as expected. Re(CO)3-diimine complexes, including those reported in this work, show Re-N bonds ranging from ~2.14–2.26 Å.19

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of 2–6. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths and angles are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement parameters†

| Compound | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emp. form | C15H10ClN2O4Re | C15H10ClN2O4Re | C15H10BrN2O4Re | C15H10BrN2O4Re | C15H10BrN2O4Re |

| Form. weight | 503.90 | 502.89 | 548.36 | 547.35 | 548.36 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P2(1)/c | P2(1)/n | P2(1)/n | P2(1)/n | P2(1)/n |

| a/Å | 21.5722(15) | 13.005(3) | 12.4869(15) | 12.577(3) | 13.186(3) |

| b/Å | 7.9755(5) | 8.8892(18) | 9.2091(11) | 9.011(2) | 8.966(2) |

| c/Å | 18.3057(12) | 13.661(3) | 13.9549(16) | 14.165(3) | 13.615(3) |

| α(°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β(°) | 96.441(2) | 100.583(2) | 100.1460(10) | 99.942(3) | 100.260(3) |

| γ(°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 3129.6(4) | 1552.4(5) | 1579.6(3) | 1581.3(6) | 1583.9(6) |

| Z | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Dc (Mg/m3) | 2.139 | 2.152 | 2.306 | 2.299 | 2.300 |

| μ (mm−1) | 7.957 | 8.020 | 10.242 | 10.231 | 10.215 |

| F(000) | 1904 | 948 | 1024 | 1020 | 1024 |

| reflns collected | 39281 | 9681 | 12874 | 11591 | 11654 |

| Data/Restraints/Parameters | 10044/0/415 | 2393/8/246 | 3492/14/209 | 3075/34/220 | 2998/35/246 |

| GOF on F2 | 0.904 | 0.943 | 0.811 | 0.705 | 0.867 |

| R1 (on Fo2, I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0263 | 0.0286 | 0.0376 | 0.0467 | 0.0437 |

| wR2 (on Fo2, I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0581 | 0.0616 | 0.0975 | 0.1518 | 0.1154 |

| R1 (all data) | 0.0407 | 0.0366 | 0.0443 | 0.0625 | 0.0622 |

| wR2 (all data) | 0.0653 | 0.0661 | 0.1038 | 0.1746 | 0.1321 |

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [deg] for compounds 1–6

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths | ||||||

| Re(1)-Cl(1) | 2.4894(12) | 2.4986(9) | 2.399(12) | - | - | - |

| Re(1)-Br(1) | - | - | - | 2.6177(8) | 2.5671(12) | 2.542(2) |

| Re(1)-N(1) | 2.173(4) | 2.182(3) | 2.174(5) | 2.173(6) | 2.185(7) | 2.161(8) |

| Re(1)-N(2) | 2.183(4) | 2.177(3) | 2.175(5) | 2.179(6) | 2.191(6) | 2.178(8) |

| Re(1)-C(1) | 1.949(5) | 1.924(4) | 1.934(8) | 1.913(7) | 1.912(10) | 1.931(9) |

| Re(1)-C(2) | 1.921(5) | 1.920(4) | 1.907(7) | 1.923(7) | 1.924(9) | 1.901(8) |

| Re(1)-C(3) | 1.916(4) | 1.918(4) | 1.919(17) | 1.937(2) | 1.9203(18) | 1.942(2) |

| Bond angles | ||||||

| N(1)-Re(1)-N(2) | 74.42(14) | 74.28(11) | 74.9(2) | 74.4(2) | 75.4(3) | 74.7(3) |

| C(1)-Re(1)-C(2) | 86.48(19) | 90.31(15) | 88.4(3) | 90.9(3) | 88.7(4) | 89.2(3) |

| C(1)-Re(1)-C(3) | 88.1(2) | 90.33(16) | 86.4(5) | 87.8(3) | 88.1(4) | 86.8(5) |

For each compound the phenyl ring is rotated out of the plane of the diimine ligand. Compounds 1 and 4 have dihedral angles between pyridine-diimine and phenol planes of ~56.8 and ~55.4º, respectively, while the angle in compounds 3 and 6 is ~57.5º. Compound 5, displays a dihedral angle of ~53.7º, similar to those seen in the ortho and para analogues, but the tilts observed for compound 2 are ~42.7 and ~67.2º for the two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The structures of the unmodified phenyl variants exhibit tilt angles of ~34.1º (X = Cl) and ~35.2º (X = Br).16, 20 In the para-chloro and para-iodo compounds (X = Br), the tilt angles are observed to be ~ 44.0 and ~46.2º respectively.21, 22 It is unclear if packing in the crystal is the reason that 2 has different rotation angles than the other compounds. What is clear is that the para- and meta- derivatives should have unhindered rotation of the phenyl ring, while phenyl ring rotation for the ortho-derivative is restricted.

Deprotonation studies

Previously, the effect of phenolic deprotonation of 1 was investigated. UV-visible spectra were recorded following sequential addition of aliquots of the base t-butylimino-tris(dimethylamino)phosphorane. A change to a blue color was observed upon addition of the base. Two isosbestic points were judged to be consistent with the phenoxide anion as the only other absorbing species in the solution.13

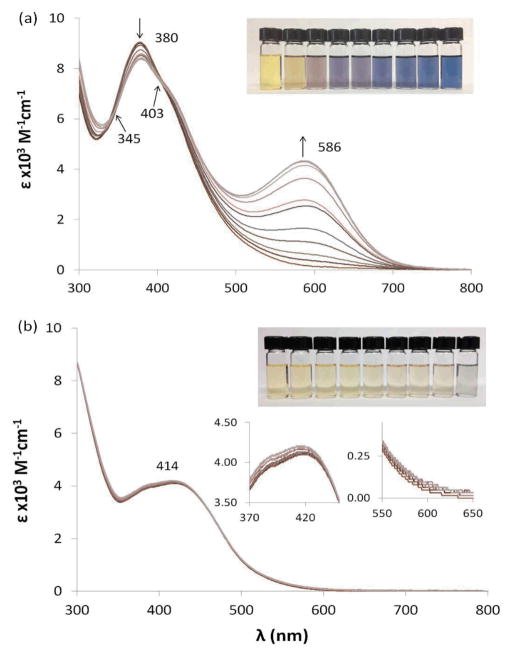

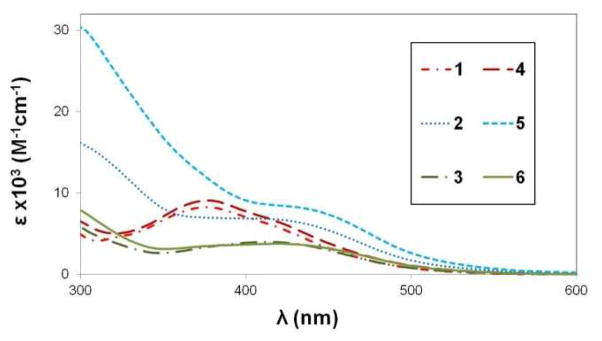

In order to examine the impact of moving the hydroxide group and varying the halide, we treated THF solutions of 1–6 with THF solutions of TMAH (tetramethyl ammonium hydroxide). Absorbance spectra were recorded after allowing reactions to equilibrate. The pairs of ortho-, meta-, and para-hydroxide compounds behaved similarly after treatment with TMAH. Compounds 1 and 4 showed a gradual decrease in intensity of a band near 380 nm and growth of a new band at 586 nm. Overlaid spectra following the titration of 4 with TMAH are shown in Fig. 3. Isosbestic points were observed at 345 and 403 nm. This deprotonation was reversible upon the addition of acid to the blue colored solution.

Fig. 3.

Overlaid UV-visible absorption spectra of 4 (a) and 6 (b) in THF upon addition of 0.0–1.0 equivalent TMAH.

Compounds 3 and 6 showed more modest changes with the increase of absorbance intensity, which corresponded with a slight darkening of the yellow color of these solutions. Notably, compounds 2 and 5, the meta-hydroxide derivatives, showed no color change upon addition of base and no change in the absorbance spectrum.

The dramatic spectral changes for 1 and 4 can be explained as arising from an extended conjugation system formed upon deprotonation. Similar behavior is observed in phenolic azo dyes. Scheme 2 shows how deprotonation leads to an extended π-system that could result in the appearance of intense bands. Compounds 3 and 6 do not show dramatic spectral changes; it is possible that restricted rotation does not permit an extended conjugated system with the halide and the imine hydrogen preventing the phenyl ring from achieving a geometry that is co-planar with the diimine ligand. Alternatively, it is possible that hydrogen bonding of the ortho-phenolic hydrogen with the halide could hinder deprotonation. With the negative charge localized in the meta position, compounds 2 and 5 are not able to extend their π-systems (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed electron flow for the compounds bearing para- (top) and ortho-OH-(bottom).

Conclusions

Diimine rhenium(I) tricarbonyl species exhibit interesting photophysical properties due to their metal-to-ligand charge transfer transitions. By coupling this diimine with a base-sensitive phenol, we can generate compounds that exhibit pH-dependent UV-visible transitions. Changes in colour were observed for compounds 1, 3, 4 and 6 when tetramethylammonium hydroxide was added into a THF solution of each compound, and the degree of color change was dependent on the position of the phenol group. No change was observed for 2 and 5, where the phenol is in the meta position. We can justify these changes based on a combination of resonance arguments and steric restrictions. None of the observed photophysical changes were dependent on the identity of the halide. We are continuing our investigations into rhenium tricarbonyl compounds both as mimics for technetium radiopharmaceuticals and as organometallic chromophores.

Experimental

Materials and methods

Starting materials were obtained commercially and used without further purification. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 MHz spectrometer (for 1 and 3) and a Varian Mercury 300 MHz spectrometer (for 2, 4, 5 and 6). Chemical shifts were reported with respect to residual solvent peaks as internal standard (d6-DMSO, δ = 2.50 ppm; 13C: d6-DMSO, δ = 39.7 ppm). ATR-IR spectra for 1 and 3 were recorded on a Perkin Elmer-Spectrum One spectrometer. FTIR spectra for 2, 4, 5 and 6 were recorded on a Nicolet iS5 spectrometer using NaCl disks. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlab of Norcross, GA 30091. Electrospray MS (ES- 5MS; positive mode) spectra were recorded using a Bruker HCT-ultra ETD II Ion Trap mass spectrometer.

X-ray data collection and structure determination

X-ray crystallographic analysis: Single crystals of 2–6 were coated in Paratone-N (Exxon) oil, mounted on a pin and placed on a goniometer head under a stream of nitrogen cooled to 100 K. The based X-ray diffractometer system equipped with a Mo-target X-ray tube (λ= 0.71073 Å) operated at 2000 W power (compounds 3–6) or a Bruker Kappa APEX II DUO CCD-based diffractometer with Cu/Mo ImuS microfocus optics (compound 2). The frames were integrated with the Bruker SAINT software package using a narrow-frame algorithm. Data were corrected for absorption effects using the multiscan method (SADABS) and the structure was solved and refined using the Bruker SHELXTL Software Package until the final anisotropic full-matrix, least-squares refinement of F2 converged.23

Synthesis of 1

This compound has been previously synthesized via a two-step method. For the current study, a one-pot method was employed. Re(CO)5Cl (50 mg, 0.125 mmol) and one equivalent of 4-aminophenol (13.5 mg, 0.125 mmol) were combined in a round-bottom flask. One equivalent of pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde (0.011 mL, 0.125 mmol) was added after the addition of 5.0 mL of methanol. The clear, colorless solution turned yellow upon the addition of the aldehyde. The 4 h reflux resulted in a dark-red, clear data were collected on either a Bruker SMART APEX I CCD-solution. The solvent was then removed by rotary evaporation. The product was dried under vacuum, and collected as a red solid. Yield: 88%.

Synthesis of 2

Compound 2 was prepared in a similar fashion to 1. The product was dried under vacuum, and collected as a red solid. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation in methanol. FTIR (cm−1): 3423 (br, w), 2022 (s), 1898 (s). Yield: 72%. Anal. Calc. for C15H10N2O4ReCl(C7H8)0.5(H2O)0.5; C, 39.71; H, 2.70; N, 5.01%. Found: C, 39.84; H, 2.98; N, 5.01%. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): δ9.98 (s, 1H, OH), 9.30 (s, 1H, H-C=N), 9.05 (d, 3J = 5.4 Hz 1H, H on py), 8.34 (m, 2H, H on py), δ7.83 (m, 1H, H on py), 7.34 (t, 3J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol), 6.98–6.94 (m, 2H, CH on phenol), 6.88–6.84 (m, 1H, CH on phenol). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO): δ198.2 (CO), 197.4 (CO), 188.1 (CO), 169.9 (C=N), 158.5 (C on py), 155.5 (C on py), 153.5 (C on py), 152.1 (C on py), 140.9 (C on py), 130.8 (C on phenol), 130.7 (C on phenol), 130.2 (C on phenol), 116.5 (C on phenol), 113.0 (C on phenol), 109.8 (C on phenol). ES-MS: m/z = calc. for C15H10N2O4ReNa: 527.00 found 526.80. UV-Vis (nm, εx 104 M−1cm−1): 290 (2.2), 259 (2.8).

Synthesis of 3

Compound 3 was prepared in a similar fashion to 1. Crystals florets, suitable for X-ray diffraction, were obtained by vapor diffusion of hexane into a methylene chloride solution of the complex. Yield: 55%. Anal. Calc. for C15H10N2O4ReCl; C, 36.92; H, 2.07; N, 5.24%. Found: C, 34.83; H, 2.02; N, 5.27%. ATR-IR (cm−1): 3269 (w), 2024 (s), 1903 (s). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): δ10.24 (s, 1H, OH), 9.29 (s, 1H, H-C=N), 9.04 (d, 3J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, H on py), 8.33 (m, 2H, H on py), 7.61 (m, 1H, H on py), 7.30 (m, 1H, CH on phenol), 7.21 (m, 2H, CH on phenol), 7.17 (m, 1H, CH on phenol). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO): δ171.9 (C=N), 155.2 (C on py), 153.6 (C on py), 148.8 (C on py), 141.0 (C on py), 130.6 (C on py), 138.5 (C on phenol), 130.2 (C on phenol), 129.7 (C on phenol), 124.6 (C on phenol), 119.4 (C on phenol), 117.2 (C on phenol). ES-MS: m/z calc. for C15H10N2O4ReNa: 527.00 found 526.80. UV-Vis (nm, εx 103 M−1cm−1): 411 (4.1), 290 (7.6), 240 (15.3).

Synthesis of 4

The diimine, pyca-C6H4-p-OH, was synthesized as described previously.13 The diimine (49 mg, 0.25 mmol) was refluxed with 50 mg, 0.125 mmol, of Re(CO)5Br for 18 h in toluene. The orange solution was evaporated to produce an orange product 4 which was washed with diethyl ether. FTIR (cm−1): 3319 (w), 2021 (s), 1899 (s). Yield: 66%. Anal. Calc. for C15H10N2O4ReBr; C, 32.85; H, 1.84; N, 5.11%. Found: C, 32.96; H, 1.68; N, 5.03%. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): δ10.02 (s, 1H, OH), 9.20 (s, 1H, H-C=N), 9.05 (d, 3J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H on py), 8.31 (m, 2H, H on py), 7.78 (m, 1H, H on py), 7.45 (d, 3J = 8.7 Hz, 2H, CH on phenol), 6.91 (d, 3J = 8.7 Hz, 2H, CH on phenol). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO): δ197.7 (CO), 197.1 (CO), 187.6 (CO), 167.8 (C=N), 159.0 (C on py), 155.8 (C on py), 153.5 (C on py), 143.1 (C on py), 140.8 (C on py), 130.4 (C on phenol), 129.7 (C on phenol), 124.4 (C on phenol), 116.2 (C on phenol). ES-MS: m/z calc. for C15H10N2O4Re+: 467.00 found 467.01, calc. for C15H10N2O4ReNa: 571.00 found 570.91. UV-Visible (nm, ε × 104 M−1cm−1): 348 (3.7).

Synthesis of 5

Re(CO)5Br (50 mg, 0.125 mmol) and pyridine-2- carboxaldehyde (0.023 mL, 0.25 mmol) were mixed using the minimum amount of toluene (15 mL) as a solvent. After five minutes, the mixture turned purple and then 3-aminophenol (27 mg, 0.25 mmol) was added to the solution to the solution. The reaction was refluxed for 12 hours. The solution was evaporated producing a red solid product which was washed with diethyl ether. Yield: 96%. FTIR (cm−1): 3387 (w), 2021 (s), 1894 (s). Anal. Calc. for C15H10N2O4ReBr(C7H8)0.25; C, 35.20; H, 2.12; N, 4.90%. Found: C, 35.12; H, 2.31; N, 4.92%. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): δ9.99 (s, 1H, OH), 9.27 (s, 1H, H-C=N), 9.07 (d, 3J = 5.4, 1H, H on py), 8.35–8.33 (m, 2H, H on py), δ7.84–7.79 (m, 1H, H on py), 7.34 (t, 3J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol), 6.99–6.94 (m, 2H, CH on phenol), 6.87–6.84 (m, 1H, CH on phenol). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO): δ197.8 (CO), 196.9 (CO), 187.5 (CO), 169.9 (C=N), 158.5 (C on py), 155.5 (C on py), 153.7 (C on py), 152.2 (C on py), 140.8 (C on py), 130.9 (C on phenol), 130.7 (C on phenol) 130.1(C on phenol), 116.5 (C on phenol), 113.1 (C on phenol), 109.8 (C on phenol). ES-MS: m/z calc. for C15H10N2O4Re+: 467.00 found 467.01, calc. for C15H10N2O4ReNa: 571.00 found 570.93. UV-Vis (nm, ε × 104 M− 1cm−1): 298 (3.0), 254 (3.9).

Synthesis of 6

Compound 6 was prepared in a similar fashion to 5. Yield: 61%. FTIR (cm−1): 3397 (m), 2023 (s), 1904 (s). Anal. Calc. for C15H10N2O4ReBr(C6H7NO)0.5; C, 35.85; H, 2.26; N, 5.81%. Found: C, 35.97; H, 2.18; N, 5.61%. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO): δ10.28 (s, 1H, OH), 9.30 (s, 1H, H-C=N), 9.10 (d, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H on py), 8.36 (m, 2H, H on py), 7.83 (m, 1H, H on py), 7.37 (d, 3J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol), 7.23 (t, 3J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol), 7.05 (d, 3J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol), 6.94 (t, 3J =8.0 Hz, 1H, CH on phenol). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO): δ198.1 (CO), 197.2 (CO), 187.8 (CO), 171.8 (C=N), 155.3 (C on py), 153.8 (C on py), 148.8 (C on py), 140.8 (C on py), 138.8 (C on py), 130.6 (C on phenol), 130.1 (C on phenol) 129.7(C on phenol), 124.7 (C on phenol), 119.4 (C on phenol), 117.2 (C on phenol). ES-MS: m/z calc. for 5C15H10N2O4Re+: 467.00 found 467.01, calc. for C15H10N2O4ReNa: 571.00 found 570.91. UV-Visible (nm, ε × 104 M−1cm−1): 374 (4.4).

Deprotonation studies

A 1.08 mM solution of TMAH in THF was prepared. Aliquots of this solution were added to a THF solution of compounds 1–6. UV-Visible spectroscopy was used to record changes that occurred upon titration. Upon addition of acid, the original spectra was obtained.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 2.

UV-visible spectra for complexes 1–6 in THF.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Akron for support of this research and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0840446 and CHE-9977144) for funds used to purchase the diffractometers used in this work. C. J. Z. acknowledges the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number R15 GM083322) for funds used in this work. R.S.H. would like to thank the Petroleum Research Fund (grant number 51085-UR3) for financial support of this research.

Footnotes

CCDC- 929875 - 929879 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper for compounds 2–6. This data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Contributor Information

Richard S. Herrick, Email: rherrick@holycross.edu.

Christopher J. Ziegler, Email: ziegler@uakron.edu.

References

- 1.Herrick RS. New Developments in Organometallic Research. Nova Science Publishers, Inc; New York: 2006. pp. 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schibli R, Schubiger PA. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:1529–1542. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schibli R, Schwarzbach R, Alberto R, Ortner K, Schmalle H, Dumas C, Egli A, Schubiger PA. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:750–756. doi: 10.1021/bc015568r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JD, Perutz RN, Moore JN. Chem Commun. 2000:1865–1866. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Bilio AJ, Crane BR, Wehbi WA, Kiser CN, Abu-Omar MM, Carlos RM, Richards JH, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3181–3182. doi: 10.1021/ja0043183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge Q, Corkery TC, Humphrey MG, Samoc M, Hor TSA. Dalton Trans. 2009:6192–6200. doi: 10.1039/b902800e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nazeeruddin MK, Klein C, Liska P, Grätzel M. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:1460–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raszeja L, Maghnouj A, Hahn S, Metzler-Nolte N. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:371–376. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasser G, Pinto A, Neumann S, Sosniak AM, Seitz M, Merz K, Heumann R, Metzler-Nolte N. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:2304–2313. doi: 10.1039/c2dt12114j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaffer P, Gleave JA, Lemon JA, Reid LC, Pacey LKK, Farncombe TH, Boreham DR, Zubieta J, Babich JW, Doering LC, Valliant JF. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephenson KA, Banerjee SR, Besanger T, Sogbein OO, Levadala MK, McFarlane N, Lemon JA, Boreham DR, Maresca KP, Brennan JD, Babich JW, Zubieta J, Valliant JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8598–8599. doi: 10.1021/ja047751b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinze K, Reinhardt S. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:9482–9486. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Heinze K. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:9554–9564. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00393j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrick RS, Wrona I, McMicken N, Jones G, Ziegler CJ, Shaw J. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:4848–4855. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qayyum H, Herrick RS, Ziegler CJ. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:7442–7445. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10665a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Spingler B, Alberto R. Inorg Chim Acta. 2003;355:386–393. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinhardt S, Heinze K. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 2006;632:1465–1470. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa R, Barone N, Gorczycka C, Powers EF, Cupelo W, Lopez J, Herrick RS, Ziegler CJ. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:2163–2170. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberto R, Schibli R, Egli A, Schubiger AP, Abram U, Kaden TA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7987–7988. doi: 10.1021/ic980112f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominey RN, Hauser B, Hubbard J, Dunham J. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:4754–4758. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehghanpour S, Mahmoudi A. Acta Cryst Sect E. 2010;66:m1335. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810037104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalaj M, Dehghanpour S, Aleeshah R, Mahmoudi A. Acta Cryst Sect E. 2010;66:m1647. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810044211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL, Crystallographic Software Package, Version 6.10. Bruker-AXS; Madison, WI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.