Abstract

AIM: To transplant undifferentiated embryonic stem (ES) cells into the spleens of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-treated mice to determine their ability to differentiate into hepatocytes in the liver.

METHODS: CCl4, 0.5 mL/kg body weight, was injected into the peritoneum of C57BL/6 mice twice a week for 5 wk. In group 1 (n = 12), 1 x 105 undifferentiated ES cells (0.1 mL of 1 x 106/mL solution), genetically labeled with GFP, were transplanted into the spleens 1 d after the second injection. Group 2 mice (n = 12) were injected with 0.2 mL of saline twice a week, instead of CCl4, and the same amount of ES cells was transplanted into the spleens. Group 3 mice (n = 6) were treated with CCl4 and injected with 0.1 mL of saline into the spleen, instead of ES cells. Histochemical analyses of the livers were performed on post-transplantation d (PD) 10, 20, and 30.

RESULTS: Considerable numbers of GFP-immunopositive cells were found in the periportal regions in group 1 mice (CCl4-treated) on PD 10, however, not in those untreated with CCl4 (group 2). The GFP-positive cells were also immunopositive for albumin (ALB), alpha-1 antitrypsin, cytokeratin 18, and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha on PD 20. Interestingly, most of the GFP-positive cells were immunopositive for DLK, a hepatoblast marker, on PD 10. Although very few ES-derived cells were demonstrated immunohistologically in the livers of group 1 mice on PD 30, improvements in liver fibrosis were observed. Unexpectedly, liver tumor formation was not observed in any of the mice that received ES cell transplantation during the experimental period.

CONCLUSION: Undifferentiated ES cells developed into hepatocyte-like cells with appropriate integration into tissue, without uncontrolled cell growth.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cells, Hepatic differentiation, Intrasplenic transplantation, Carbon tetrachloride

INTRODUCTION

Embryonic stem (ES) cells are self-renewing and multipotent cells derived from the inner cell masses of preimplantation blastocysts[1,2], and have many characteristics of an optimal cell source for cell-replacement therapy. Theoretically, ES cells are able to be produced limitlessly, and various kinds of cell-types have been generated in vitro and in vivo. Thus, ES cells are considered to have potential to become an optimal cell source for cell-replacement therapy.

We previously showed that mouse ES cells have an ability to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in vitro using an attached culture of embryoid bodies (EBs)[3] and demonstrated that introduction of transcription factor gene hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 beta, which plays an important role in liver development, led to an efficient induction of ES cells into hepatocyte-like cells[4,5]. The in vitro capability of ES cells to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells has also been proven by other investigators[6-21]. In general, the methods used in those studies can be divided into spontaneous and directed differentiation. For spontaneous differentiation, the formation of embryoid bodies (EBs) has been mostly utilized[6-11]. With directed differentiation, different processes of enrichment of a specific differentiated cell type that use elements to promote the differentiation of ES cells into an endodermal lineage, such as the addition of growth factors (GFs) and hormones[12-20], and the constitutive expression of hepatic transcription factors[21], have been utilized.

In contrast to a number of reports of hepatic differentiation of ES cells in vitro, the behavior of transplanted ES cells in the liver has not been reported, except for the formation of teratomas[9,22]. According to the results of a study that utilized intravenous transplantation of a relatively large number of undifferentiated ES cells (2 × 106/mouse)[9], tumor formation was observed in the livers of all carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-treated mice, but not in mice with normal livers. Although the tumors formed in the livers contained ES-derived mature hepatocytes, few cells seemed to have been integrated into the ordinary structure of the residual normal livers. Recently, bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) were demonstrated to differentiate into hepatocytes and integrate into the liver after intravenous transplantation in CCl4-treated mice, even without in vitro induction directed toward an endoderm or hepatocyte lineage[23]. Those results suggested that the livers in CCl4-mice provide a microenvironment necessary for the lodging of BMSCs or ES cells, and their subsequent differentiation into hepatocytes.

In the present study, we investigated whether ES cells are able to differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. For this purpose, we transplanted a reduced number of undifferentiated ES cells (1 × 105/mouse) into the spleens of CCl4-treated experimental and CCl4-untreated control mice, expecting that tumors would develop in the livers. We found that the native ES cells migrated to the liver and developed into hepatocyte-like cells in CCl4-treated mice, but not in the CCl4-untreated control mice. Further, localization of migrated ES cells in the CCl4-mice livers was found in the periportal regions on post-transplantation day (PD) 10 and the cells were immuno-positive for albumin (ALB), alpha-1 antitrypsin (α1AT), and cytokeratin 18 (CK18) on PD 20. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4α), an important transcription factor for mature hepatocytes, was also detected immunohistochemically. Interestingly, most of the GFP-positive cells showed immuno-positivity to DLK, a hepatoblast marker, on PD 10. Although there were very few ES-derived cells demonstrated immunohistologically in the livers on PD 30, improvements in liver fibrosis were observed. Unexpectedly, formation of liver tumors was not observed in any of the mice that received transplanted cells during the experimental period.

Our results suggest that undifferentiated ES cells can develop into hepatocyte-like cells with appropriate integration into tissue without invariably leading to uncontrolled cell growth. In the future era of cell growth control, undifferentiated ES cells may be directly used for therapeutic transplantation as well as terminally differentiated derivatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Murine ES cell line

We utilized G4-2 cells from a mouse ES cell line (129/SvJ mouse ES cells, a kind gift from Dr. Hitoshi Niwa, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan). The G4-2 cells were derived from EB3 ES cells[24,25] and carried an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene under the control of the CAG expression unit. EB3 ES cells are a subline derived from E14tg2a ES cells[26] and carry the blasticidin S-resistant selection marker gene driven by the Oct-3/4 promoter (active under undifferentiated status). For the present study, undifferentiated G4-2 cells were maintained on gelatin-coated dishes without feeder cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma; St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO/BRL; Grand Island, NY;), 0.1 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 10 mmol/L nonessential amino acids (GIBCO/BRL), 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate (Sigma), and 1400 U/mL of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; GIBCO/BRL). For some of the experiments, G4-2 cells were cultured in medium containing 10 μg/mL of blasticidin S to eliminate differentiated cells.

Preparation of graft cells

Culture dishes (9 cm in diameter), used to maintain the undifferentiated ES colonies, were washed with 8 mL of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) 3 times and then treated with 1.0 mL of 0.025% trypsin/PBS for 2 min at 37°C. Five milliliters of ES maintenance medium containing 10% FBS was added to the culture dish to stop trypsin activity. Single cell solutions were easily obtained by repeated pipetting. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS 3 times and finally prepared for transplantation in a PBS solution at a cell concentration of 1 × 106/mL.

CCl4 treatment

To induce liver damage, CCl4 at 0.5 mL/kg of body weight was injected into the peritoneum twice a week for 5 wk.

Grouping of experimental animals

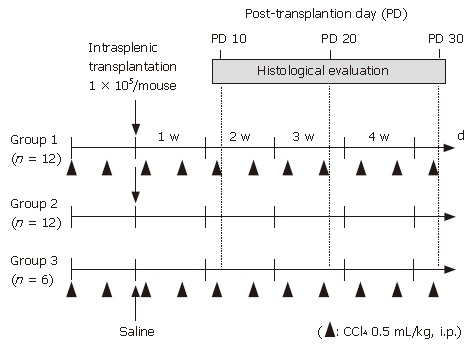

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) at 6 wk of age and used as experimental animals. All procedures including the surgical steps were performed in accordance with the Guidelines of Nara Medical University for experiments involving animals and recombinant DNA. The mice were divided into 3 groups. Group 1 (n = 12) received CCl4 treatment and transplantation of graft cells. One day after the second injection of CCl4, 1 × 105 GFP-positive undifferentiated ES cells (0.1 mL of 1 × 106/mL solution) were transplanted into the spleen. Briefly, a 1-cm incision was made on the left flank and the spleen was extracted through the incision. Then, 0.1 mL of the graft cell solution (1 × 106 cells/mL) was slowly infused into the inferior pole of the spleen using a 31-gauge needle and a Hamilton syringe. Once the infusion was complete, the syringe was left in place for 1 min. Group 2 mice (n = 12) were injected in the same manner with 0.2 mL of saline twice a week, instead of CCl4, and transplanted with the same amount of ES cells into the spleen as Group 1. Group 3 mice (n = 6) were treated with CCl4 and injected with 0.1 ml of saline into the spleen in the same manner, instead of ES cells. Grouping and an outline of the experiments are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Grouping of experimental animals. Female C57BL/6 mice were divided into 3 groups. Intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 at 0.5 mL/kg body weight was performed twice a week in group 1 mice (n = 12) and group 3 mice (n = 6), while 0.2 mL of saline was injected instead of CCl4 in group 2 mice (n = 12). One day after the second intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 or saline, 1 x 105 GFP-positive undifferentiated ES cells (0.1 mL of 1 x 106/mL solution) were transplanted into the spleens in groups 1 and 2, whereas no cell transplantation was performed with group 3.

Tissue preparation

The livers were thoroughly perfused via the heart with 4% paraformaldehyde to wash out contaminating blood cells. For fixation, the perfused livers were incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, then soaked in 30% sucrose for 3 d. Tissues were frozen on dry ice and then sectioned into 5-μm slices using a cryostat in preparation for dyeing.

Immunohistochemistry and double immunofluorescence for GFP

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed in accordance with previously reported methods[27]. Frozen tissue sections were desiccated completely at room temperature using a dryer, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times for 5 min each, and soaked in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) once for 5 min. Sections were incubated overnight with anti-GFP (1:1000, Molecular Prove Inc, OR, USA and Nacalai Tesque Inc, Kyoto, Japan), anti-ALB (1:100, Biogenesis Ltd, England, UK), anti-α1AT (1:100, Zymed Laboratories Inc, CA, USA), anti-CK18 (1:100, Chemicon International Inc, CA, USA), anti-CK19 (1:100, Abcam Ltd, Cambridge, UK), anti-HNF4α (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, CA, USA), and anti-DLK[28] (1:100) antibodies. Tissue sections were then washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min each and incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-rat (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse) IgG (1:200, Vector Laboratories Inc, CA, USA) secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C, then washed 3 times for 5 min each with diluted water. Next, for the purpose of intrinsic peroxidase elimination, the tissue sections were immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 30 min, then washed 3 times for 5 min each with PBS. The sections were incubated with Vectastain ABCR reagent (Vector Laboratories Inc, CA, USA) for 2 h at 37°C, then washed 3 times for 5 min with diluted water and treated with 0.02 mol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 4% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Vector Laboratories Inc, CA, USA) in the presence of 0.0004% H2O2 for 2 min at room temperature. Stained sections were rinsed with diluted water, and immersed in ethanol and xylene for complete dehydration. Finally, the sections were enclosed with Entellan-newR.

For fluorescent immunohistochemistry, tissue sections were incubated with Alexa FluorR 488 and 546 goat anti-rat (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse) IgG (H + L) conjugate (Molecular Prove Inc, OR, USA) secondary antibodies for 1 h, then washed 3 times for 5 min each with PBS. Sections were mounted on glass slides from an Anti-fade Kit (Molecular Prove Inc, OR, USA). Positive cells in the liver were observed using a Provis microscope (Olympus, Tokyo) equipped with a charge coupled device (CCD) camera. A total of 10 different areas in each liver section were analyzed independently for each mouse.

RESULTS

Migration of ES cells into CCl4-treated mouse livers

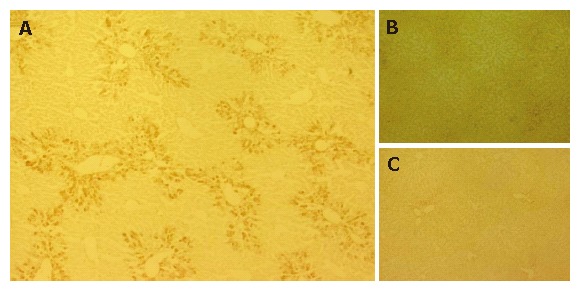

GFP-immuno-positivity was examined in the liver specimens 10 d after intrasplenic transplantation (PD 10 of 1 × 105 GFP-positive ES cells (groups 1 and 2) or intrasplenic injection of saline (group 3) (Figure 2). A distinct distribution of immunoreactivity against GFP was observed in the liver sections of group 1 mice, which were treated with CCl4 and grafted with ES cells (Figure 2A). Further, GFP-positive cells were present in the periportal regions of the hepatic lobules. However, no GFP-positive cells were detected in liver sections from group 2 mice (not treated with CCl4, grafted with ES cells) (Figure 2B), or in those from group 3 mice (treated with CCl4, not grafted with ES cells) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Migration of ES cells into CCl4-treated mouse livers.GFP-immuno-positivity was examined in the liver specimens on PD 10. A: Immunoreactivity against GFP was clearly observed in the liver sections of Group 1 mice and GFP was predominantly distributed in the portal regions; B, C: No GFP-positive cells were detected in liver sections of group 2 (B) and group 3 mice (C).

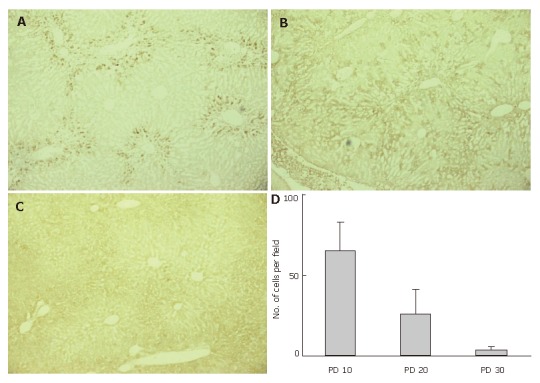

GFP-immuno-positivity was also examined in the liver specimens on PD 20 and 30 (Figure 3). Immunoreactivity to GFP was detected in the liver sections from group 1 mice on PD 20 (Figure 3B), though the intensity was weaker than that on PD 10. On PD 30, scant or no GFP-immuno-positivity was detected in group 1 mice (Figure 3C). We also counted the number of GFP-positive cells in 10 microscopic fields, focusing on the periportal area. The average numbers of GFP-positive cells around the portal vein on PD 10, 20, and 30 were 65 ± 18, 26 ± 15, and 4.0 ± 2.0 respectively, in each microscopic field at 400 × magnification (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Disappearing GFP-immuno-positivity.GFP-immuno-positivity on PD 10, 20, and 30 was examined using liver specimens from group 1 mice. A: GFP-immunoreactivity was clearly observed in the periportal regions on PD 10; B: GFP-immunoreactivity was still detected on PD 20, though the intensity was weaker than on PD 10. Cells presenting GFP-immunoreactivity were more inwardly distributed in the hepatic lobules, as compared to PD 10; C: Scant or no GFP-immuno-positivity was detected on PD 30; D: The average numbers of GFP-positive cells around the portal vein were determined after examining 10 microscopic fields in the periportal area at 400 x magnification.

Expression of hepatocyte-related markers in GFP-positive cells

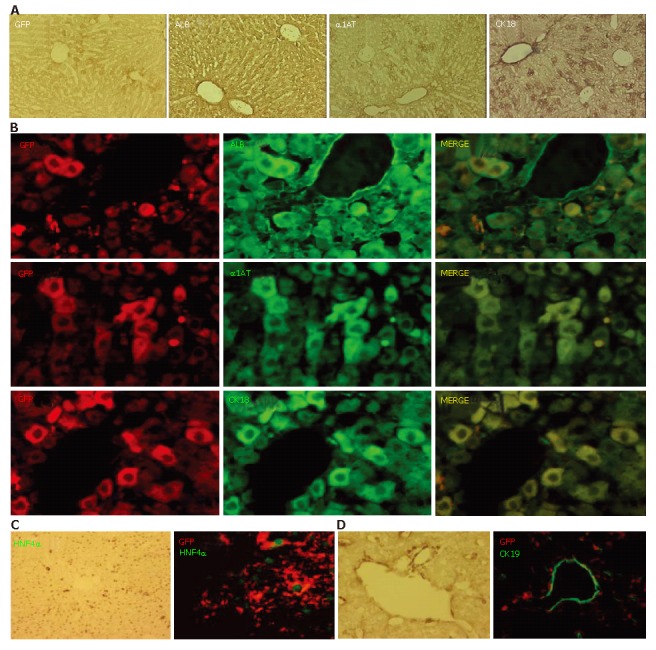

Nearly all of the GFP-positive cells had disappeared from the livers of the transplanted mice by PD 30, however, considerable numbers of GFP-positive cells were present in the hepatic lobules for a limited period in those in group 1. Next, we utilized immunohistochemistry to examine the expressions of ALB, α1AT, and CK18 on PD 20 (Figure 4A). ALB immuno-positivity was observed homogeneously throughout the hepatic lobules without discrimination between the periportal regions and the other parts. Immuno-positivity for α1AT and CK18 was also observed throughout the lobules, though some cells located in the periportal area showed a higher level of intensity. Double immunofluorescent studies on PD 20 demonstrated that most of the GFP-immuno-positive cells expressed ALB, α1AT, and CK18 (Figure 4B). Further, the expression of HNF4α, a transcription factor necessary for complete differentiation of hepatocytes in vivo[29], was confirmed in GFP-immuno-positive cells (Figure 4C). In contrast to the expression of hepatocyte-related markers on GFP-positive cells, there were no CK19-positive ES-derived cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Expression of hepatocyte-related markers on GFP-positive cells. A: Prior to conducting immunofluorescent studies, the expression of GFP, ALB, α1AT, and CK18 on PD 20 was examined using a conventional method; B, C: Double immunofluorescent studies on PD 20 demonstrated that most of the GFP-immuno-positive cells expressed ALB, α1AT, and CK18; C: Expression of HNF4α was confirmed in the GFP-immuno-positive cells; D: There were no CK19-positive ES-derived cells.

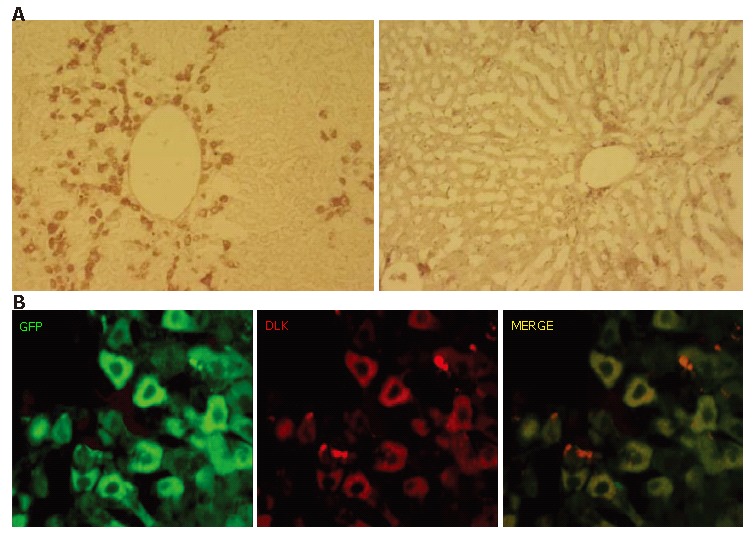

Expression of hepatoblast marker on GFP-positive cells

Next, we used an antibody against DLK for an immunohistochemical examination of the involvement of recapitulating developmental processes. DLK is a molecule identified as a possible hepatoblast marker and known to be strongly expressed on hepatoblasts in mouse embryonic livers until embryonic d 16.5, after which it becomes downregulated and disappears by birth[28]. Immunoreactivity against DLK was clearly observed in the periportal regions on PD 10 (Figure 5A, left), though few DLK-immuno-positive cells were present in the hepatic lobules on PD 20 (Figure 5A, right). A double immunofluorescent study on PD 10 showed that the DLK-immuno-positive cells were also GFP-immuno-positive (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Expression of hepatoblast marker DLK on GFP-positive cells. A: DLK-immuno-positivity was examined on PD 10 (left) and PD 20 (right). A number of cells showed immunoreactivity against DLK on PD 10, whereas there were few on PD 20; B: Most of GFP-immunopositive cells on PD 10 were positive for DLK.S.

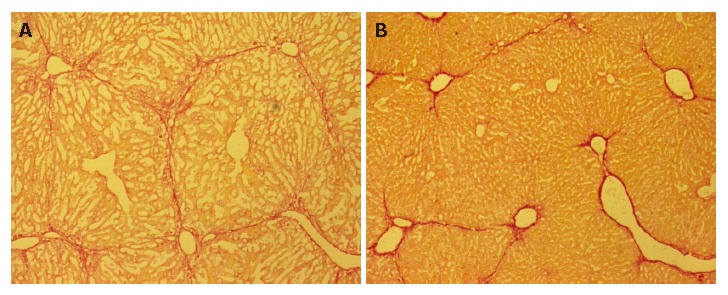

Decreased fibrosis after ES transplantation

Liver fibrosis was histologically evaluated using picro-Sirius red staining. Representative liver sections stained with Sirius red are shown in Figure 6. The five-week treatment with CCl4 induced liver fibrosis in group C mice, whereas decreased fibrosis was observed in group 1, which received ES cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Decreased fibrosis after ES transplantation. Liver fibrosis was histologically evaluated on PD 30 using picro-Sirius red staining. Representative liver histology results for group 3 (A) and group 1 (B) mice. Decreased fibrosis was observed in group 1 mice, as compared to those in group 3.

Tumor formation

All of the livers in the experimental animals were removed and the lobes sliced into 2-mm widths, with specimens from the middle lobes used for microscopic analysis. No tumor formation was observed macroscopically or microscopically in any of the livers. All of the spleens were also examined macroscopically and microscopically, and no tumors were found. Further, no tumor development in any organs other than the liver and spleen was observed for up to 30 d after transplantation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that ES cells migrated to the liver and differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells after intrasplenic transplantation. It is reasonable to speculate that generation of a favorable microenvironment is required in the recipient liver for undifferentiated ES cells to differentiate into hepatocytes. We adopted a method of repeated CCl4 administration to induce undifferentiated ES cells into hepatocyte-like cells. It has been reported that BMSCs intravenously transplanted into mice that received repeated CCl4 treatments migrated to the liver and differentiated into hepatocytes[23], suggesting that a favorable condition was generated in the CCl4-treated livers to trap exogenously administered BMSCs and allow them differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells. Although the mechanisms by which a CCl4-treated liver favors hepatic differentiation of BMSCs remain to be elucidated, we considered that CCl4 treatment provides a suitable condition for ES cells to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in a manner similar to that for BMSCs. In addition to the differentiation of BMSCs into hepatocyte-like cells in vivo, that of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into hepatocyte-like cells has been reported using a coculture with hepatocytes from CCl4-treated livers[30]. Based on those reports, we transplanted ES cells into CCl4-treated livers of mice with the expectation that they would differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells.

We found that ES cells migrated into the livers of the CCl4-treated mice, whereas no such migration was observed in CCl4-untreated mice. The migrated ES cells, shown by GFP-immuno-positivity, were distributed in the periportal regions on PD 10 and 20, and disappeared by PD 30. GFP-immuno-positive ES-derived cells in the livers on PD 20 were also immuno-positive for the hepatocyte-related markers ALB, α1AT, and CK18, suggesting their successful differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells. Further, the expression of HNF4α, an important transcription factor for hepatocyte maturation, was also observed in the ES-derived cells in our immunohistochemical examination. These results suggest that a CCl4-treated liver has the ability to support homing and hepatic differentiation of undifferentiated ES cells.

It is difficult to fully elucidate the mechanisms involved with generation of ES-derived hepatocyte-like cells in the liver. However, we considered that recapitulation of the developmental process in the liver may have a role. In the present study, we tested for immunopositive reactions to DLK, which is a molecule that has been identified as a possible hepatoblast marker and shown to be strongly expressed on hepatoblasts in mouse embryonic livers until embryonic d 16.5, after which it was downregulated and disappeared by birth[28]. DLK-positive cells were detected and found to have a similar distribution as GFP-positive cells in the CCl4-treated livers, as they were markedly present in the periportal regions on PD 10 and few in number on PD 20. Most of the GFP-positive cells were also immuno-positive for DLK on PD 10. These results strongly suggest that mechanisms similar to those related to hepatocyte development are involved in generating ES-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Apart from the involvement of recapitulated liver development, it is known that oval cells are activated to proliferate following extensive and chronic liver damage with inhibited proliferation of hepatocytes[31,32]. Those cells are considered to represent a type of hepatic stem cells derived from the canal of Hering[33-35]. Although we did not examine for the presence of oval cells in the present study, some GFP-positive grafted cells may also express markers for those cells, as shown in the case of BMC transplantation to CCl4-treated mice.

Because of the risk of tumor formation, we transplanted small numbers of undifferentiated ES cells in the present study. Using a rat model of Parkinson’s disease, it was initially reported that transplantation of small numbers of mouse ES cells increases the influence of the host tissue and allows for default differentiation[36]. Therefore, we used 105 cells for intrasplenic transplantation, which was 20-fold fewer than the number of transplanted ES cells in a previous report[9], in which teratoma formation in the liver was documented. Nevertheless, we expected teratoma development, because ES cells in an undifferentiated state were utilized as graft cells. However, no tumors developed in the livers or spleens in the mice that received transplants up to the end of the 30-d experimental period. This observation might be explained by the disappearance of GFP-immuno-positive cells from the liver by PD 30. PCR analysis of liver tissue specimens collected on PD 30 using a GFP-specific primer set failed to reveal PCR products (data not shown), suggesting the absence of transplanted ES cells or ES-derived cells in the liver. A previous study[23] reported that transplanted BMSC cells were retained in the liver under conditions of persistent CCl4 treatment. We consider that one of the reasons for the elimination of grafted ES cells seen in our study was because of the allogeneic transplantation method utilized, as the grafted ES cells were derived from 129SVJ mice and the donor mice were C57BL6, even though 129SVJ and C57BL6 are classified as the same haplotype, H-2b. It is conceivable that an immunological barrier may eliminate non-self-grafted cells, leading to the absence of ES-derived cells and no occurrence of tumor formation.

Interestingly, a reduction of liver fibrosis was observed on PD 30 in CCl4-treated mice that underwent ES-cell transplantation, despite the absence of grafted cells in the liver. It has been reported that transplantation of BMSCs[37] and BM-derived mesenchymal stem cells[38] had a protective effect against fibrosis in livers chronically damaged by administration of CCl4. However, no results of the effects of ES cells on hepatic fibrosis are known to have been reported. Thus, there may be some common mechanisms underlying the improvement of hepatic fibrosis following the transplantation of cells with stem cell characteristics, as has been reported in the case of BMSCs.

Recently, it was reported that mouse undifferentiated ES cells fused with mouse bone marrow cells and neural stem cells in vitro[39,40]. Further, hybrid hepatocytes were produced by cell fusion between embryoid body-derived cynomolgus monkey ES cells and hepatocytes from uPA/SCID mice[41]. In the present study, we did not investigate whether generation of GFP-immuno-positive hepatocyte-like cells in the liver was due simply to the differentiation of the transplanted ES cells, or to cell fusion between ES cells and hepatocytes. In the near future, we intend to perform FISH analyses using a set of mouse chromosome X- and Y-specific probes.

In conclusion, we found that undifferentiated ES cells grafted into the spleen migrated to the liver and developed into hepatocyte-like cells without apparent tumor formation in CCl4-treated mice. Although a prolonged presence of grafted cells in the liver was not observed, a beneficial effect of inhibiting fibrosis was obtained by the present single transplantation method. In the coming era of control of cell growth, undifferentiated ES cells may be directly used for therapeutic transplantation as well as terminally differentiated derivatives.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Lu W

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada T, Yoshikawa M, Kanda S, Kato Y, Nakajima Y, Ishizaka S, Tsunoda Y. In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells identified by cellular uptake of indocyanine green. Stem Cells. 2002;20:146–154. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-2-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanda S, Shiroi A, Ouji Y, Birumachi J, Ueda S, Fukui H, Tatsumi K, Ishizaka S, Takahashi Y, Yoshikawa M. In vitro differentiation of hepatocyte-like cells from embryonic stem cells promoted by gene transfer of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 beta. Hepatol Res. 2003;26:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishizaka S, Shiroi A, Kanda S, Yoshikawa M, Tsujinoue H, Kuriyama S, Hasuma T, Nakatani K, Takahashi K. Development of hepatocytes from ES cells after transfection with the HNF-3beta gene. FASEB J. 2002;16:1444–1446. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0806fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe K, Niwa H, Iwase K, Takiguchi M, Mori M, Abé SI, Abe K, Yamamura KI. Endoderm-specific gene expression in embryonic stem cells differentiated to embryoid bodies. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:27–34. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones EA, Tosh D, Wilson DI, Lindsay S, Forrester LM. Hepatic differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2002;272:15–22. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyashita H, Suzuki A, Fukao K, Nakauchi H, Taniguchi H. Evidence for hepatocyte differentiation from embryonic stem cells in vitro. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinzei R, Tanaka Y, Shimizu-Saito K, Hara Y, Kakinuma S, Watanabe M, Teramoto K, Arii S, Takase K, Sato C, et al. Embryoid-body cells derived from a mouse embryonic stem cell line show differentiation into functional hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36:22–29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumashiro Y, Asahina K, Ozeki R, Shimizu-Saito K, Tanaka Y, Kida Y, Inoue K, Kaneko M, Sato T, Teramoto K, et al. Enrichment of hepatocytes differentiated from mouse embryonic stem cells as a transplantable source. Transplantation. 2005;79:550–557. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153637.44069.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asahina K, Fujimori H, Shimizu-Saito K, Kumashiro Y, Okamura K, Tanaka Y, Teramoto K, Arii S, Teraoka H. Expression of the liver-specific gene Cyp7a1 reveals hepatic differentiation in embryoid bodies derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1297–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamazaki T, Iiboshi Y, Oka M, Papst PJ, Meacham AM, Zon LI, Terada N. Hepatic maturation in differentiating embryonic stem cells in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuai XL, Cong XQ, Li XL, Xiao SD. Generation of hepatocytes from cultured mouse embryonic stem cells. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1094–1099. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu AB, Cai JY, Zheng QC, He XQ, Shan Y, Pan YL, Zeng GC, Hong A, Dai Y, Li LS. High-ratio differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes in vitro. Liver Int. 2004;24:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kania G, Blyszczuk P, Jochheim A, Ott M, Wobus AM. Generation of glycogen- and albumin-producing hepatocyte-like cells from embryonic stem cells. Biol Chem. 2004;385:943–953. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jochheim A, Hillemann T, Kania G, Scharf J, Attaran M, Manns MP, Wobus AM, Ott M. Quantitative gene expression profiling reveals a fetal hepatic phenotype of murine ES-derived hepatocytes. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:23–29. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15005571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirahashi H, Wu J, Yamamoto N, Catana A, Wege H, Wager B, Okita K, Zern MA. Differentiation of human and mouse embryonic stem cells along a hepatocyte lineage. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:197–211. doi: 10.3727/000000004783984016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imamura T, Cui L, Teng R, Johkura K, Okouchi Y, Asanuma K, Ogiwara N, Sasaki K. Embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies in three-dimensional culture system form hepatocyte-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1716–1724. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubo A, Shinozaki K, Shannon JM, Kouskoff V, Kennedy M, Woo S, Fehling HJ, Keller G. Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development. 2004;131:1651–1662. doi: 10.1242/dev.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teratani T, Yamamoto H, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Asari A, Quinn G, Sasaki H, Terada M, Ochiya T. Direct hepatic fate specification from mouse embryonic stem cells. Hepatology. 2005;41:836–846. doi: 10.1002/hep.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson-Dushnik M, Benvenisty N. Involvement of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 in endoderm differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3817–3822. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi D, Oh HJ, Chang UJ, Koo SK, Jiang JX, Hwang SY, Lee JD, Yeoh GC, Shin HS, Lee JS, et al. In vivo differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:359–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terai S, Sakaida I, Yamamoto N, Omori K, Watanabe T, Ohata S, Katada T, Miyamoto K, Shinoda K, Nishina H, et al. An in vivo model for monitoring trans-differentiation of bone marrow cells into functional hepatocytes. J Biochem. 2003;134:551–558. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura F, Yoshikawa M, Kanda S, Nonaka M, Yokota H, Shiroi A, Nakase H, Hirabayashi H, Ouji Y, Birumachi J, et al. Potential use of embryonic stem cells for the treatment of mouse parkinsonian models: improved behavior by transplantation of in vitro differentiated dopaminergic neurons from embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:171–180. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper M, Hardy K, Handyside A, Hunter S, Monk M. HPRT-deficient (Lesch-Nyhan) mouse embryos derived from germline colonization by cultured cells. Nature. 1987;326:292–295. doi: 10.1038/326292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29:577–580. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanimizu N, Nishikawa M, Saito H, Tsujimura T, Miyajima A. Isolation of hepatoblasts based on the expression of Dlk/Pref-1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1775–1786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Ning G, Duncan SA. Mammalian hepatocyte differentiation requires the transcription factor HNF-4alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:464–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang YY, Collector MI, Baylin SB, Diehl AM, Sharkis SJ. Hematopoietic stem cells convert into liver cells within days without fusion. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:532–539. doi: 10.1038/ncb1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen BE, Zajac VF, Michalopoulos GK. Hepatic oval cell activation in response to injury following chemically induced periportal or pericentral damage in rats. Hepatology. 1998;27:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paku S, Schnur J, Nagy P, Thorgeirsson SS. Origin and structural evolution of the early proliferating oval cells in rat liver. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theise ND, Saxena R, Portmann BC, Thung SN, Yee H, Chiriboga L, Kumar A, Crawford JM. The canals of Hering and hepatic stem cells in humans. Hepatology. 1999;30:1425–1433. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saxena R, Theise N. Canals of Hering: recent insights and current knowledge. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:43–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Bai XF, Huang CX. Hepatic stem cells: existence and origin. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:201–204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjorklund LM, Sánchez-Pernaute R, Chung S, Andersson T, Chen IY, McNaught KS, Brownell AL, Jenkins BG, Wahlestedt C, Kim KS, et al. Embryonic stem cells develop into functional dopaminergic neurons after transplantation in a Parkinson rat model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2344–2349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022438099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakaida I, Terai S, Yamamoto N, Aoyama K, Ishikawa T, Nishina H, Okita K. Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1304–1311. doi: 10.1002/hep.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao DC, Lei JX, Chen R, Yu WH, Zhang XM, Li SN, Xiang P. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect against experimental liver fibrosis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3431–3440. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, Hoki M, Mastalerz DM, Nakano Y, Meyer EM, Morel L, Petersen BE, Scott EW. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okamura K, Asahina K, Fujimori H, Ozeki R, Shimizu-Saito K, Tanaka Y, Teramoto K, Arii S, Takase K, Kataoka M, et al. Generation of hybrid hepatocytes by cell fusion from monkey embryoid body cells in the injured mouse liver. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;125:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]