Abstract

Despite progress in the treatment of advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer (PC), the outcome of this disease remains dismal for the majority of patients. Given the moderate efficacy of treatment, prognostic factors may help to guide treatment decisions. Several trials identified baseline performance status as an important prognostic factor for survival. Unfit patients with a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) below 70% only have a marginal benefit from chemotherapy with gemcitabine (Gem) and may often benefit more from optimal supportive care. Once, however, the decision is taken to apply chemotherapy, KPS may be used to select either mono- or combination chemotherapy. Patients with a good performance status (KPS = 90%-100%) may have a significant and clinically relevant survival benefit from combination chemotherapy. By contrast, patients with a poor performance status (KPS ≤ 80%) have no advantage from intensified therapy and should rather receive single-agent treatment.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Gemcitabine, Pancreatic cancer, Performance status, Prognostic factor

INTRODUCTION

Advanced pancreatic cancer (PC) is an incurable disease and without appropriate treatment survival is limited to 3-4 mo. Since Burris et al[1] demonstrated the superiority of gemcitabine (Gem) over bolus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), single-agent Gem has evolved as a standard of care. Numerous trials consistently support the notion that Gem alone may induce a median overall survival (OS) of 5-7 mo and a 1-year-survival of 11%-25%[2]. A great effort has been undertaken to improve these results by use of combination chemotherapy. Up to now, only two combinations, Gem plus erlotinib[3] and Gem plus capecitabine[4] have provided a significant prolongation of survival when compared to Gem alone.

Due to the moderate progress derived from chemo-therapy, the question arises if subgroups of patients can be identified who benefit most from specific treatment strategies. Previous studies already tried to identify prognostic factors such as pre-treatment CA 19-9 levels[5,6], inflammatory response markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) or cytokines[7,8], serum-albumin levels[9] or pre-treatment performance status[10-12]. In this overview we analysed Karnofsky performance status (KPS) as a prognostic factor to define a patient group which may benefit from more intensive therapy as opposed to those patients who should rather receive single-agent treatment.

CLINICAL TRIALS

Single-agent therapy

The clinical importance of the KPS for the outcome of PC patients treated with Gem was first elucidated by Storniolo and co-workers[13]. Within an investigational new drug treatment program 3023 patients were evaluated. The analysis of baseline efficacy factors indicated that patients with a KPS ≥ 70% had a median survival of 5.5 mo as compared to only 2.4 mo observed in patients with a KPS < 70%. Also median time to disease progression (TTP) was greater in the good performance group (2.9 vs 1.7 mo, respectively). Interestingly, best tumor response was comparable between the two groups (12% vs 10%) supporting the notion that in PC response to therapy is only a poor surrogate endpoint for survival. In view of this analysis, it appears unlikely that patients with a KPS < 70% actually benefit from therapy and the conclusion may be drawn that chemotherapy with Gem should rather be withheld in patients with a very poor performance status.

Gemcitabine plus Cisplatin

The combination of Gem and cisplatin is based on a synergistic cytotoxic interaction of the two agents, namely the propensity of Gem to inhibit repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage. In a randomized phase III trial Gem plus cisplatin was compared to single-agent Gem[14]. In the combination arm, Gem (1000 mg/m2) and cisplatin (50 mg/m2) were both applied in a biweekly fashion, while in the single-agent arm Gem was given at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 weekly times three in a 4-wk regimen. One hundred ninety-five patients with histologically confirmed advanced PC (KPS > 70%) were randomized and survival was evaluated as the primary end-point.

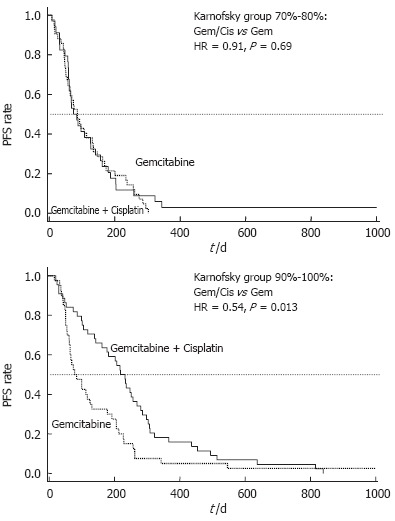

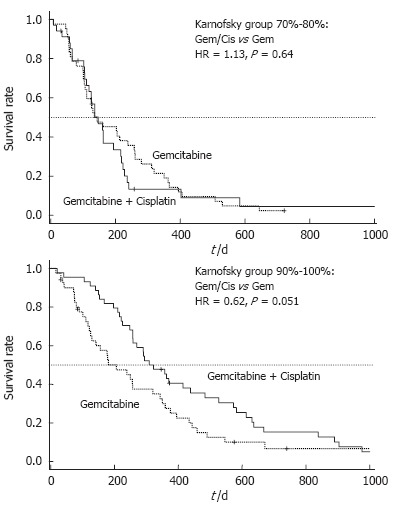

In a post-hoc analysis of this trial, patients were divided into groups with good (KPS = 90%-100%) and poor performance status (KPS = 70%-80%). Patients with a poor performance status at base-line (KPS 70%-80%) had no benefit from combination therapy as compared to Gem alone and comparably disappointing results were obtained for progression free survival (PFS: 2.8 vs 2.9 mo, P = 0.69) and OS (4.9 vs 4.8 mo, P = 0.64) (Table 1). By contrast, patients with a good KPS (90%-100%) who underwent treatment with Gem/cisplatin had a significantly longer PFS compared to patients treated with single-agent Gem (7.7 vs 2.8 mo, P = 0.013) (Figure 1). This prolongation of PFS also translated into a prolonged median OS (10.7 vs 6.9 mo), that reached a borderline level of statistical significance (P = 0.051) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Influence of performance status on median survival in randomized phase III trials

|

Overall Survival (mo) |

Reference | ||

| KPS 60-80 | KPS 90-100 | ||

| Gemcitabine + Cisplatin | 4.91 | 10.7 | Heinemann et al |

| Gemcitabine | 4.81 | 6.9 | |

| Statistical significance | P = 0.64 | P = 0.051 | |

| Gemcitabine + 5-FU/FA | 3.4 | 8.5 | Riess et al |

| Gemcitabine | 4.9 | 6.2 | |

| Statistical significance | P = 0.62 | P = 0.172 | |

| Gemcitabine + Capecitabine | 5.3 | 10.1 | Herrmann et al |

| Gemcitabine | 7.0 | 7.5 | |

| Statistical significance | P = 0.22 | P = 0.024 | |

KPS = Karnofsky performance status,

subgroup with poor performance status defined as KPS 70%-80%.

Figure 1.

Randomized phase III trial comparing gemcitabine (Gem) vs gemcitabine plus cisplatin (Cis): Subgroups KPS 70%-80% and KPS 90%-100%; Progression-free survival (PFS) by treatment arm (HR = hazard ratio).

Figure 2.

Randomized phase III trial comparing gemcitabine (Gem) vs gemcitabine plus cisplatin (Cis): Subgroups KPS 70%-80% and KPS 90%-100%; Overall survival (OS) by treatment arm (HR = hazard ratio).

In the univariate analysis for prognostic factors, KPS (HR = 0.52, P = 0.006) and stage of disease (HR = 1.55, P = 0.0048) had a significant impact on survival, while age, gender, tumor grading and treatment arm did not. These data were confirmed in a multivariate analysis which identified KPS (HR = 0.59, P = 0.0051) and stage of disease (HR = 1.65, P = 0.022) as independent determinants of overall survival[14].

Gemcitabine plus 5-FU

The CONKO-002 trial compared the combination of Gem plus folinic acid (FA) and 5-FU to single-agent Gem[15]. In this randomized phase III trial Gem was given at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 together with FA 200 mg/m2 and 5-FU 750 mg/m2 weekly times four every six weeks. In the comparator arm, single-agent Gem was applied according to the Burris regimen (1000 mg/m2 weekly × 7 followed by two weeks rest and a subsequent application on d 1, 8, and 15 every four weeks[1]). Both treatment arms induced nearly identical results for tumor response rates (Gem/FA/5-FU vs Gem: RR = 4.8% vs 7.2%), median time to tumor progression (TTP = 3.5 vs 3.5 mo), and median survival time (OS = 5.9 vs 6.2 mo). Also in this trial, the subgroup analysis indicated that patients with a poor performance status (KPS = 60%-80%) responded in a different way compared to the good performance group (KPS = 90%-100%). In patients with a poor performance status, combination treatment induced a worse survival than gemcitabine alone (3.4 vs 4.9 mo). By contrast, a strong trend towards an improved survival was observed in the good performance group treated within the combination arm (8.5 vs 6.2 mo, P = 0.172) (Table 1).

Gemcitabine plus Capecitabine

Herrmann and co-workers performed a randomized trial comparing Gem (1000 mg/m2, d 1 + 8, q 3 wk) plus capecitabine (650 mg/m2 po bid d 1-14 q 3 wk) to Gem given according to the Burris-regimen[16]. While the combination induced a higher median PFS than Gem alone (4.8 vs 4.0 mo) and a longer median OS (8.4 mo vs 7.3 mo), these results failed to reach the level of statistical significance. In the unfavorable KPS group (60%-80%), survival with Gem/capecitabine was inferior to Gem alone (5.3 vs 7.0 mo), while in the good performance group the combination induced a significantly superior survival time (10.1 vs 7.5 mo, P = 0.024) (Table 1).

CONCLUSION

Despite recent advances in systemic treatment of patients with advanced PC, the prognosis still remains poor. Thus, pre-treatment patient selection, based on prognostic factors, for different therapeutic options (e.g. supportive care only, single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy) may turn out to gain clinical importance. Additionally, these prognostic factors may also be a useful for the design of future trials in advanced PC.

In the present review, we summarized the clinical importance of performance status as a prognostic factor for OS. In a randomized trial comparing Gem plus cisplatin to Gem alone potential prognostic factors such as stage of disease, KPS, treatment arm, age, sex, and pathological tumor grade were evaluated in a univariate analysis. Only pre-treatment KPS and distant metastasis could be identified as significant prognostic factors for OS. In a multivariate analysis, both could be confirmed as independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS[14]. The importance of performance status has already been observed by Louvet and co-workers who compared the Gem plus oxaliplatin combination to single-agent Gem[12]. He reported that distant metastasis and a poor PS (ECOG 2) at baseline were independent negative prognostic factors. These data were further supported by van Cutsem et al[9] who investigated the efficacy of Gem plus tipifarnib in a large randomized phase III trial. ECOG performance status and stage of disease (locally advanced vs metastatic) were, besides tumor differentiation and albumin levels, highly significant prognostic factors for survival in a univariate analysis.

Once performance status is defined as a clinically relevant prognosticator for patient outcome, the question needs to be asked if performance status can also be used to guide adequate treatment selection. Storniolo et al[13] clearly demonstrated that the benefit from single-agent Gem is very low if patients with a KPS < 70% are treated. More often than not these patients will rather benefit from optimal supportive care.

Once, however, the decision is taken that a patient should receive chemotherapy it needs to be clarified if combination or single-agent chemotherapy is likely to provide an optimal therapeutic result. The relevance of KPS in this particular question was investigated based on a randomized trial comparing the Gem/cisplatin combination to Gem alone. In a retrospective subgroup analysis, patients with a good KPS (90%-100%) had a clear benefit from the Gem/cisplatin combination with regard to PFS (7.7 vs 2.8 mo, P = 0.013) and OS (10.7 vs 6.9 mo, P = 0.051). Outcome of patients with a poor KPS (70%-80%) was, however, not affected by the choice of treatment. Similar observations were also reported in two further phase III trials[15,16]. While none of them demonstrated a significant superiority of combination chemotherapy for the whole study population, both trials could show a clinical relevant benefit for patients with a good performance status.

In conclusion, Gem-based combination regimens have the potential to prolong survival in patients with a good KPS, whereas patients with a poor KPS have no advantage and may as well receive single-agent Gem. Consideration of the performance status may, therefore, help to select adequate treatment strategies and thus may provide a reasonable step towards individualized therapy. Individualization of treatment becomes necessary since the benefit from more intensive combination chemotherapy can only be expected in defined subgroups of PC patients.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Liu WF

References

- 1.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinemann V. Gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer: a comparative analysis of randomized trials. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:9–16. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Finger A, Hecht J, Gallinger S, Au H, Ding K, Christy-Bittel J, Parulekar W. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared to gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinicals trials group [NCIC-CTG] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken D, Davies C, Dunn J, Valle J, Smith D, Steward W, Harper P, Neoptolemos J. Phase III randomised comparison of gemcitabine (GEM) versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine (GEM-CAP) in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2005;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saad ED, Machado MC, Wajsbrot D, Abramoff R, Hoff PM, Tabacof J, Katz A, Simon SD, Gansl RC. Pretreatment CA 19-9 level as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2002;32:35–41. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:32:1:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maisey NR, Norman AR, Hill A, Massey A, Oates J, Cunningham D. CA19-9 as a prognostic factor in inoperable pancreatic cancer: the implication for clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:740–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawaki A, Kanemitsu Y, Mizuno N, Takahashi K, Nakamura T, Ioka T, Tanaka S, Nakaizumi A, Salem AA, Ueda R, et al. Practical prognostic index for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1292–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebrahimi B, Tucker SL, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Kurzrock R. Cytokines in pancreatic carcinoma: correlation with phenotypic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer. 2004;101:2727–2736. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawlowski A, Schoffski P, Post S, Verslype C, Neumann H, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1430–1438. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishii H, Okada S, Nose H, Yoshimori M, Aoki K, Okusaka T. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with systemic chemotherapy. Pancreas. 1996;12:267–271. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno H, Okada S, Okusaka T, Ikeda M. Prognostic factors in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma receiving systemic chemotherapy. Oncology. 2000;59:296–301. doi: 10.1159/000012186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, André T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taïeb J, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storniolo AM, Enas NH, Brown CA, Voi M, Rothenberg ML, Schilsky R. An investigational new drug treatment program for patients with gemcitabine: results for over 3000 patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1261–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekäs H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Clemens M, Heinrich B, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–3952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riess H, Helm A, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Moik M, Hammer C, Zippel K, Weigang-Köhler K, Stauch M, Oettle H. A randomised, prospective, multicenter phase III trial of gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), folinic acid vs gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Saletti P, Bajetta E, Schueller J, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W. Gemcitabine (G) plus Capecitabine (C) versus G alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: A randomized phase III study of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group (CECOG) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4010. [Google Scholar]