Abstract

AIM: To comparatively evaluate the long term efficacy of Rifaximin and dietary fibers in reducing symptoms and/or complication frequency in symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease.

METHODS: 307 patients (118 males, 189 females, age range: 40-80 years) were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to: Rifaximin (400 mg bid for 7 d every month) plus dietary fiber supplementation (at least 20 gr/d) or dietary fiber supplementation alone. The study duration was 24 mo; both clinical examination and symptoms’ questionnaire were performed every two months.

RESULTS: Both treatments reduced symptom frequency, but Rifaximin at a greater extent, when compared to basal values. Symptomatic score declined during both treatments, but a greater reduction was evident in the Rifaximin group (6.4 ± 2.8 and 6.2 ± 2.6 at enrollment, p = NS, 1.0 ± 0.7 and 2.4 ± 1.7 after 24 mo, p < 0.001, respectively). Probability of symptom reduction was higher and complication frequency lower (Kaplan-Meyer method) in the Rifaximin group (p < 0.0001 and 0.028, respectively).

CONCLUSION: In patients with symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease, cyclic administration of Rifaximin plus dietary fiber supplementation is more effective in reducing both symptom and complication frequency than simple dietary fiber supplementation. Long term administration of the poorly absorbed antibiotic Rifaximin is safe and well tolerated by the patients, confirming the usefulness of this therapeutic strategy in the overall management of diverticular disease.

Keywords: Dietary fiber, Antibiotics, Abdominal symptoms, Diverticulitis

INTRODUCTION

Diverticular disease of the colon represents the most common disease affecting the large bowel in the Western world[1]; the disease is more frequent in USA than in Europe and it represents a rare clinical condition in Africa[2]. Prevalence of diverticular disease is largely age-dependent and is uncommon, with a rate less than 5%, in subjects under 40 years of age, increasing up to 65% in those aged 65 years or more[3]. Diverticular disease and its clinical consequences have recently become increasingly prevalent, paralleling western patterns of living and eating, the ageing population, and economic and industrial development[4]. Although a large majority of patients with diverticular disease will remain entirely asymptomatic for their entire life, 20% of them may manifest clinical illness[4,5] and a worse quality of life[6]. Furthermore, since available data[2,3] suggest that the incidence of diverticular disease is increasing and that its prevalence increases with age, the identification of a management strategy for the disease represents an healthy priority. Several guidelines are actually available to manage diverticular disease[7,8]; there is a consensus that conservative treatment is indicated in patients with a first attack of uncomplicated diverticulitis, since about 70% of patients treated for a first episode recover and have no further problems[9]. However, a 60% risk of developing complications has been reported in patients with recurrent attacks[2]. Conservative treatment is aimed at the relief of symptoms and at preventing major complications[8,9]. Available evidence[10] suggests that antibiotics, and namely topical antibiotics, and dietary fibers represent useful treatments for uncomplicated diverticular disease and for preventing disease complications. Different antibiotics have been tested, but the possibility of side effect development due to their long-term use have discouraged their employment[10].

Rifaximin is a rifamycin analogue with a broad spectrum of activity similar to that of rifampicin and it is poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract[11], thus conferring to this drug a high safety profile. Due to these properties, Rifaximin has been tested in different gastrointestinal diseases, and in diverticular disease too[12,13]. Two randomized clinical trials[14,15] performed in patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease showed that Rifaximin plus dietary fiber supplementation was more effective in improving symptoms than dietary fibre supplementation alone after 12 mo of treatment.

Since the uncertainties regarding the natural history of the disease, and in particular the predictors for the progression from uncomplicated to complicated disease, and the lack of a definite indication for long term management of uncomplicated disease, data on long-term treatment with topical antibiotics and dietary fibers would be necessary.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the long-term efficacy of cyclic administration of Rifaximin plus fiber supplementation versus fiber supplementation alone on symptoms and clinical manifestations in patients with symptomatic, but uncomplicted, diverticular disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a multicenter, open, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Patients were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment regimens: one group received Rifaximin (400 mg bid for 7 d every month) plus dietary fiber supplementation (at least 20 gr/d) (Rifaximin group) and the other group simple dietary fiber supplementation (at least 20 gr/d) (fiber group). The study duration was 24 mo.

Patients were consecutively assigned to one group or to the other by a computer-generated randomization scheme. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the study protocol was approved by the local Ethis Committee.

Patients

Consecutive patients with symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease were enrolled. Inclusion criteria for the study were: age between 40 and 80 years, endoscopic or radiological evidence of diverticular disease of the sigmoid and/or descending colon, presence of symptoms attributable to the diverticular disease of the colon such as lower abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, tenesmus, diarrhea and abdominal tenderness. Patients who referred the continuous presence of three, or more, of these symptoms for at least 1 mo before the enrolment entered in the study.

Exclusion criteria were represented by the presence of a solitary diverticulum of the right colon, signs of complicated diverticular disease, previous colonic surgery, neoplastic or haematological diseases, immunodeficiency, pregnancy and questionable ability to cooperate. Patients who assumed antibiotics in the previous 4 wk were also excluded.

Clinical evaluation

At enrolment and every 2 mo until the 24 mo patients underwent clinical examination; a questionnaire inquiring about the presence and severity of abdominal symptoms was also performed. Five clinical variables (lower abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, tenesmus, diarrhea and abdominal tenderness) were graded according to the following scale: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = mild symptoms, easily tolerated; 2 = moderate symptoms, sufficient to cause interference with normal daily activities; 3 = severe, incapacitating symptoms, with inability to perform normal daily activities. Consequently the global score could range from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 15 (presence of all symptoms with the higher degree of severity).

Biochemical tests were performed at enrolment, and after 12 and 24 mo of treatment .

Statistical methods

On the presumption of a 40% reduction at 24 mo in the frequency of symptoms with dietary fiber and a 65% reduction with Rifaximin plus fiber treatment, and considering the delta between the frequencies to be either equal to or at least 25%, a two-tail significance test, a significance level of α = 0.05, a 99% power and a 3:2 allocation ratio (in order to better satisfy the secondary end-point), the number of patients to be enrolled was 177 patients for the Rifaximin group and 110 for the fibers group. Presuming a 10% of drop-out, it was necessary to enrol 307 patients (185 for the active group and 122 for the control group)[16].

χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the distribution of categorical or absolute variables within the studied groups. Parametric tests (Levene’s test, t test, one-and two-way analysis of variance and repeated-measure ANOVA) were used to analyze continuous parameters. Non-parametric tests, one-way analysis of variance (Friedman’s test) and Wilcoxon test were applied to analyze the same parameters in subgroups of patients in whom a distribution normality of character being studied could not be presumed[17].

Kaplan Meier curves were used to estimate the probability of a reduction in symptom score and of complication development in the two groups of patients; differences between the two branches were evaluated by means of Log-rank test. Results were expressed as mean ± SD and a P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 13.0.

RESULTS

Patients

Three-hundred and seven (307) patients were enrolled, 118 males and 189 females.

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients: no difference was found between the two groups of patients in terms of gender, age and colonic distribution of the disease as well as frequency of abdominal symptoms and global symptom score. Diagnosis of diverticular disease was performed by colonoscopy in 46.2% of patients treated with Rifaximin and in 53.7% of patients treated with fibers, and by barium enema in 60.9% and 48.8% of patients, respectively (P = NS). Again, no difference was present at baseline between the two groups of treatment as far as biochemical parameters are concerned (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients

|

Rifaximin plus fibers |

Fibers |

P | |

| (n =184) | (n =123) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Males | 68 (37.0%) | 50 (40.7%) | 1NS |

| Females | 116 (63.0%) | 73 (59.3%) | |

| Age (yr) | 63.6 ± 11.7 | 60.7 ± 12.5 | 2NS |

| Site of diverticula | |||

| Left colon | 47 (25.5%) | 26 (21.1%) | |

| Colon-sigma | 59 (32.1%) | 38 (30.9%) | 3NS |

| Sigma | 73 (39.7%) | 56 (45.5%) | |

| Sigma-rectum | 5 (2.7%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| Symptoms (%) | |||

| Lower abdominal pain | 87.5% | 90.2% | 1NS |

| Bloating | 85.9% | 78.0% | 1NS |

| Tenesmus | 35.3% | 29.3% | 1NS |

| Diarrhoea | 35.9% | 32.5% | 1NS |

| Abdominal tenderness | 71.2% | 69.1% | 1NS |

| Symptoms score | 6.4 ± 2.8 | 6.2 ± 2.6 | 1NS |

χ2 test with continuity correction;

t test;

χ2 test.

Table 2.

Mean baseline values of biochemical parameters

| Rifaximin plus fibers | Fibers | P | |

| ESR (mm/h) | 24.9 ± 17.7 | 22.8 ± 17.8 | NS |

| Leukocytes (mm3) | 8128.1 ± 2377.7 | 7836.9 ± 2019.6 | NS |

| Neutrophils (mm3) | 68.3 ± 12.1 | 68.7 ± 9.6 | NS |

| Ht (%) | 41.9 ± 5.3 | 42.2 ± 4.0 | NS |

| Creatininemia (mg/dL) | 0.97 ± 0.25 | 0.98 ± 0.19 | NS |

| Blood nitrogen (mg/dL) | 38.3 ± 12.7 | 36.5 ± 11.2 | NS |

| Blood sodium (nmol/L) | 138.8 ± 4.9 | 139.4 ± 17.8 | NS |

| Potassemia (nmol/L) | 4.23 ± 0.46 | 4.15 ± 0.35 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 23.9 ± 17.2 | 21.8 ± 10.8 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 25.0 ± 23.1 | 22.1 ± 14.1 | NS |

| AP (IU/L) | 151.7 ± 65.4 | 142.4 ± 65.6 | NS |

| γGT (IU/L) | 34.8 ± 33.4 | 33.7 ± 26.1 | NS |

| Total proteins (g/dL) | 6.85 ± 0.58 | 6.90 ± 0.42 | NS |

t-test for corrected for multiple comparison.

Fourty-eight (48) patients did not complete the study, 25 patients of the Rifaximin group and 23 patients of the fibers group; 28 patients (17 of the Rifaximin group and 11 of the fibers group, P = NS, Fisher’s exact test) were drop-outs: in the Rifaximin group 14 patients refused to continue the study, 2 patients died for cardiovascular disease and 1 patient for causes unrelated to diverticular disease, while in the fibers group 10 patients refused to continue the study and 1 patient underwent surgery for gallstone disease. Side effects (mainly represented by nausea, headache and weakness) occurred in 4 patients of the Rifaximin group and in 3 patients of the fibers group (P = NS). Frequency of complications was significantly different (P = 0.041) between the two groups: in fact complications occurred in 4 patients of the Rifaximin group (2 cases of rectal bleeding, and 2 of diverticulitis) and in 9 of the fiber group (4 cases of intestinal infections, 1 of rectal bleeding and 4 of diverticulitis).

The effect of treatments on clinical signs and symptoms is illustrated in Table 3: both treatments induced a significant reduction in symptom frequency in all patients after 12 mo. After 24 mo of treatment, Rifaximin was able to further reduce symptoms as lower abdominal pain, bloating, tenesmus and abdominal tenderness while no difference was observed in patients treated with fibers alone between the results observed at the 12th and the 24th mo.

Table 3.

Symptom frequency (%) at baseline, after 12 and 24 mo of treatment

| Mo |

Rifaximin plus fibers |

Fibers |

P at 24th | ||||

| 0 | 12th | 24th | 0 | 12th | 24th | ||

| Lower abdominal pain | 87.5 | 17.2 | 12.9 | 90.2 | 28.8 | 19.2 | 0.051 |

| Bloating | 85.9 | 35.0 | 21.9 | 78.0 | 43.3 | 40.3 | < 0.0021 |

| Tenesmus | 35.3 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 29.3 | 2.9 | 9.6 | = 0.051 |

| Diarrhoea | 35.9 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 32.5 | 1.0 | 2.9 | NS2 |

| Abdominal tenderness | 71.2 | 19.0 | 6.5 | 69.1 | 35.6 | 21.2 | < 0.0011 |

χ2 test;

Fisher’s Exact test.

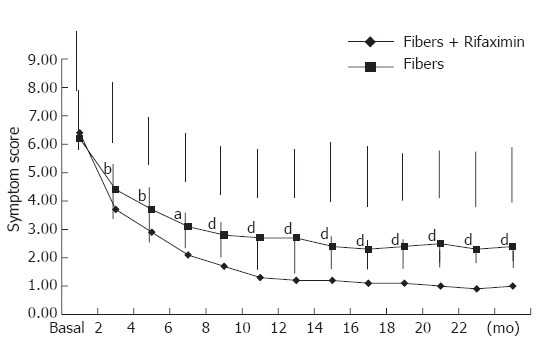

The effect of treatments on the symptomatic score is shown in Figure 1: although both treatments were able to significantly reduce the symptom score, this result was differently reached: at baseline the symptom score was similar, while at the end of the study period a significant difference (P < 0.01) was present between the Rifaximin treated group and the fiber group (1.0 ± 0.7 and 2.4 ± 1.7, respectively).

Figure 1.

Changes in symptoms score after Rifaximin plus fiber supplementation and fiber supplementation alone (mean ± SD). t test for independent samples corrected for multiple comparison: aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; dP < 0.001.

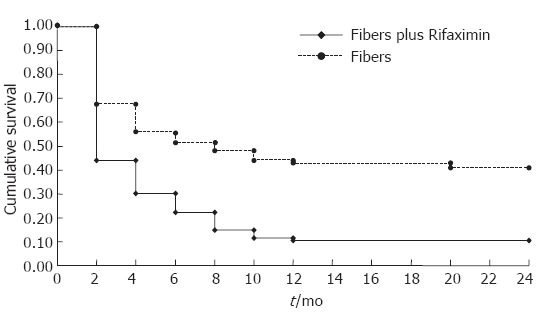

The clinical effect of the two treatments evaluated according to the Kaplan-Meier method is shown in Figure 2: the probability of symptom remission in symptomatic patients was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) in the Rifaximin group than in the control group. Although the overall clinical efficacy of the two regimens is different, a similar behaviour can be observed: the cumulative survival progressively declined during the first 12 mo of treatment, remaining constant during the following 12 mo. Rifaximin treatment was also able to induce a lower frequency of recurrence of symptoms: six (3.2%) Rifaximin treated patients had a further episode of abdominal symptoms, while in the fibers group the corresponding figure was three (9.6%) patients (P < 0.03).

Figure 2.

Probability of symptom reduction in patients treated with Rifaximin plus fibers or with fiber supplementation alone. Kaplan-Meier method: Test Log Rank: P < 0.0001.

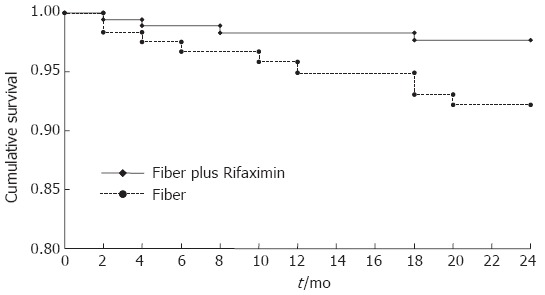

No significant alterations in biochemical tests were observed in the two groups of patients (Table 4). The probability of developing complications during the study in the two groups of patients evaluated according to the Kaplan-Meier method is illustrated in Figure 3: as observed for symptoms, Rifaximin administration documented a more favourable effect, being significantly lower (P < 0.028) the probability of developing complications with respect to fiber supplementation. Although with a different rate of probability, both treatments induced a progressively reduced frequency of complications during the whole study period.

Table 4.

Mean value of biochemical parameters before and at the end of treatment period

|

Rifaximin plus fibers |

P |

Fibers |

P | |||

| Baseline | at 24 mo | Baseline | at 24 mo | |||

| ESR (mm/h) | 24.8 ± 18.2 | 15.2 ± 14.4 | < 0.001 | 23.2 ± 18.6 | 17.8 ± 15.3 | < 0.05 |

| Leukocytes (mm3) | 8330.3 ± 2554.4 | 6515.8 ± 1393.9 | < 0.001 | 7944.9 ± 2091.4 | 6918.5 ± 1719.8 | < 0.01 |

| Neutrophils (mm3) | 67.8 ± 12.3 | 62.0 ± 10.9 | < 0.005 | 68.9 ± 9.9 | 65.5 ± 8.7 | < 0.03 |

| Creatininemia (mg/dL) | 0.98 ± 0.25 | 0.96 ± 0.21 | NS | 0.98 ± 0.19 | 0.94 ± 0.17 | NS |

| Blood nitrogen (mg/dL) | 39.4 ± 13.0 | 37.7 ± 10.6 | NS | 37.1 ± 11.3 | 33.7 ± 9.9 | < 0.05 |

| Blood sodium (nmol/L) | 138.8 ± 5.0 | 140.0 ± 5.1 | < 0.05 | 139.2 ± 5.2 | 139.1 ± 6.5 | NS |

| Potassemia (nmol/L) | 4.22 ± 0.45 | 4.21 ± 0.46 | NS | 4.20 ± 0.37 | 4.18 ± 0.30 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 23.2 ± 15.1 | 21.3 ± 12.7 | NS | 22.5 ± 11.1 | 20.8 ± 10.5 | NS |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.9 ± 14.6 | 21.8 ± 11.6 | NS | 22.7 ± 14.4 | 19.1 ± 8.8 | < 0.05 |

| AP (U/L) | 147.3 ± 63.2 | 164.3 ± 65.6 | < 0.05 | 140.6 ± 69.3 | 149.1 ± 62.4 | NS |

| γGT (U/L) | 33.0 ± 24.1 | 36.6 ± 24.3 | NS | 35.4 ± 27.3 | 30.2 ± 18.4 | NS |

| Total proteins (g/dL) | 6.85 ± 0.57 | 6.89 ± 0.58 | NS | 6.90 ± 0.44 | 6.78 ± 0.89 | NS |

t test for paired data, corrected for multiple comparison.

Figure 3.

Probability of complication development in patients treated with Rifaximin plus fibers or with fibers supplementation alone. Kaplan-Meier method. Test Log Rank: P = 0.028.

DISCUSSION

The present study suggest that the cyclic, long term administration of the non-absorbable antibiotic Rifaximin associated with dietary fiber supplementation is more effective than dietary fiber supplementation alone in reducing the clinical manifestations of patients with symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease. Furthermore, Rifaximin treatment is more effective than fiber administration influencing the clinical course of the disease, since both probability of symptom recurrence and development of disease complications are significantly reduced.

Diverticular disease of the colon is common in developed countries and its prevalence is correlated with advancing age[1-4]. Studies on the natural history of the disease[3,5,9] have indicated that most patients with colonic diverticula remain entirely asymptomatic for their lifetime. Actually there are no definitive data to support any therapeutic recommendation, or routine follow-up regimen, for asymptomatic subjects, although it is reasonable to recommend a life-style characterized by regular physical activity and a diet high in fruit and vegetable fibers[18]. According to available guidelines[7,8] in symptomatic, but uncomplicated, diverticular disease treatment is aimed at symptom-relief and at prevention of complications (diverticulitis, hemorrage). Different agents have been proposed, such as bulking agents, antispasmodics, topical antibiotics, on the basis of different potential pathophysiological mechanism/s, i.e. abnormal colonic motility, inadequate intake of dietary fibers, intestinal bacterial overgrowth and mucosal inflammation[10,19-23].

The efficacy of fiber supplementation in the treatment of symptomatic diverticular disease remains controversial, although it is considered a mainstay for treatment[10]. The efficacy of dietary fibers in reducing symptoms and in improving intestinal function is probably related to its ability to hold water, to increase luminal intestinal mass, to relax the intestinal wall and to lower the intraluminal pressure[24,25].

Antibiotics are routinely used in the treatment of inflammatory complications of diverticular disease. In symptomatic, but uncomplicated diverticular disease, the use of antibiotics seems without a rationale. However, recent studies have suggested the presence, at least in a sub-group of patients, of an intestinal bacterial overgrowth[21], a condition that may allow an excessive production of bowel gas with secondary development of abdominal pain, bloating and tenderness. Furthermore, intestinal bacterial overgrowth may contribute to maintain a chronic, low-grade mucosal inflammation, as suggested in irritable bowel syndrome[26], which could be responsible for symptom development[19].

Rifaximin has been tested in both uncontrolled[12,13] and controlled[14,15] clinical studies to treat symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease, with encouraging results.

The mechanism by which Rifaximin improves symptoms in uncomplicated diverticular disease is unclear. It has been suggested a synergistic effect of Rifaximin and high fiber diet in reducing proliferation of gut microflora, with a consequent decrease in bacterial hydrogen and methane production and/or in expanding faecal mass, due to a decrease in bacterial degradation of fibers[15,27].

Furthermore, Rifaximin may improve symptoms and lower the frequency of disease complications reducing intestinal bacterial overgrowth[19,21]. Rifaximin may also enhance faecal bulking and faecal weight, as shown for other antibiotics[28], and decrease the intraluminal colonic pressure, one of the pathogenetic mechanisms for diverticula development[20]. Due to the therapeutic uncertainties of both Rifaximin and fiber supplementation, in the present study we decided to comparatively evaluate these two agents. The results we obtained confirm and extend to a longer period previous observations by Papi et al[14] and Latella et al[15], who found that administration for 12 mo of Rifaximin plus dietary fiber supplementation was more effective in improving symptoms than dietary fibre supplementation alone. The present study documents that the efficacy of Rifaximin plus fiber supplementation is not only maintained, but it is more evident after 24 mo of treatment than fibers alone. According to the probability curves, the beneficial clinical effect of Rifaximin treatment is more pronounced during the first 12 mo, but it may last up to 24 mo. This observation is important, since it suggests a positive effect of Rifaximin treatment on the natural history of diverticular disease. Up to now, no definitive data are available regarding the way to prevent the development/maintenance of disease symptoms and complications. As far as the last point is concerned, the present study indicates that Rifaximin treatment significantly reduces the probability of complication development and that this effect is constant during the whole study period.

In conclusion the present study documents that in patients with symptomatic, uncomplicated diverticular disease, cyclic administration of Rifaximin plus fiber supplementation is more effective in reducing symptom persistence/recurrence and complication development than dietary fiber alone. Cyclic, long term administration of this non-absorbable antibiotic is safe and well tolerated by the patients, confirming the clinical usefulness of this therapeutic strategy in the overall management of diverticular disease. Further studies are needed to better identify the mechanism/s of action of both Rifaximin and of its association with dietary fibers.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Bi L

References

- 1.Stollman N, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. Lancet. 2004;363:631–639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delvaux M. Diverticular disease of the colon in Europe: epidemiology, impact on citizen health and prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18 Suppl 3:71–74. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-0673.2003.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks TG. Natural history of diverticular disease of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975;4:53–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang JY, Melville D, Maxwell JD. Epidemiology and management of diverticular disease of the colon. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:211–228. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmakis N, Tudor RG, Keighley MR. The 5-year natural history of complicated diverticular disease. Br J Surg. 1994;81:733–735. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolster LT, Papagrigoriadis S. Diverticular disease has an impact on quality of life -- results of a preliminary study. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:320–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köhler L, Sauerland S, Neugebauer E. Diagnosis and treatment of diverticular disease: results of a consensus development conference. The Scientific Committee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:430–436. doi: 10.1007/s004649901007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diagnosis and management of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad Hoc Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3110–3121. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuki A, Nagata H, Tatemichi M, Kaneda S, Tsukada N, Ishii H, Hibi T. The out-patient management of patients with acute mild-to-moderate colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:889–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson J, Spiller R. Colonic diverticular disease. Clin Evid. 2004;(12):599–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillis JC, Brogden RN. Rifaximin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in conditions mediated by gastrointestinal bacteria. Drugs. 1995;49:467–484. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199549030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papi C, Ciaco A, Koch M, Capurso L. Efficacy of rifaximin on symptoms of uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. A pilot multicentre open trial. Diverticular Disease Study Group. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1992;24:452–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventrucci M, Ferrieri A, Bergami R, Roda E. Evaluation of the effect of rifaximin in colon diverticular disease by means of lactulose hydrogen breath test. Curr Med Res Opin. 1994;13:202–206. doi: 10.1185/03007999409110484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papi C, Ciaco A, Koch M, Capurso L. Efficacy of rifaximin in the treatment of symptomatic diverticular disease of the colon. A multicentre double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latella G, Pimpo MT, Sottili S, Zippi M, Viscido A, Chiaramonte M, Frieri G. Rifaximin improves symptoms of acquired uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casagrande JT, Pike MC. An improved approximate formula for calculating sample sizes for comparing two binomial distributions. Biometrics. 1978;34:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical methods in medical research. UK: Black-Well Scientific Publication Limited, Oxford; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A prospective study of diet and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:757–764. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colecchia A, Sandri L, Capodicasa S, Vestito A, Mazzella G, Staniscia T, Roda E, Festi D. Diverticular disease of the colon: new perspectives in symptom development and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1385–1389. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassotti G, Battaglia E, De Roberto G, Morelli A, Tonini M, Villanacci V. Alterations in colonic motility and relationship to pain in colonic diverticulosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Elisei W. Assessment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in uncomplicated acute diverticulitis of the colon. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2773–2776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson JK, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis and disorders of mast cell proliferation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002;22:175–188. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:22:2:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petruzziello L, Iacopini F, Bulajic M, Shah S, Costamagna G. Review article: uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1379–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lupton JR, Turner ND. Potential protective mechanisms of wheat bran fiber. Am J Med. 1999;106:24S–27S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodribb AJ. Treatment of symptomatic diverticular disease with a high-fibre diet. Lancet. 1977;1:664–666. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, Corinaldesi R. A role for inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i41–i44. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papi C, Koch M, Capurso L. Management of diverticular disease: is there room for rifaximin? Chemotherapy. 2005;51 Suppl 1:110–114. doi: 10.1159/000081997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurpad AV, Shetty PS. Effects of antimicrobial therapy on faecal bulking. Gut. 1986;27:55–58. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]