Abstract

Objective

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with conflicted parent–child relationships. The underlying mechanisms of this association are not yet fully understood. We investigated the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between externalizing psychopathology in children with ADHD, and expressed emotion (EE; warmth and criticism) and psychopathology in mothers.

Method

In this 6-year follow-up study 385 children with an ADHD combined subtype were included at baseline (mean=11.5 years, 83.4% male), of which 285 children (74%) were available at follow-up (mean=17.5 years, 83.5% male). At both time points, measures of child psychopathology (i.e., ADHD severity, oppositional, and conduct problems), maternal EE, and maternal psychopathology (i.e., ADHD and affective problems) were obtained.

Results

EE was not significantly correlated over time. At baseline, we found a nominally negative association (p≤.05) between maternal warmth and child ADHD severity. At follow-up, maternal criticism was significantly associated with child oppositional problems, and nominally with child conduct problems. Maternal warmth was nominally associated with child oppositional and conduct problems. These associations were independent of maternal psychopathology. No longitudinal associations were found between EE at baseline and child psychopathology at follow-up, or child psychopathology at baseline and EE at follow-up.

Conclusions

The results support previous findings of cross-sectional associations between parental EE and child psychopathology. This, together with the finding that EE was not stable over six years, suggests that EE is a momentary state measure varying with contextual and developmental factors. EE does not appear to be a risk factor for later externalizing behavior in children with ADHD.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct problems, follow-up study, maternal expressed emotion, oppositional problems

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with greater family stress, parental psychopathology, and conflicted parent–child relationships1. The underlying mechanisms of these associations are not yet fully understood. A frequently applied measure of family relationships is parental expressed emotion (EE)2. EE quantifies the attitudes and emotions expressed towards family members2. We know from community studies that negative parental EE is related to higher levels of ADHD symptoms in children3,4. Likewise, parents express more negative emotions towards their child with an ADHD diagnosis compared with controls5,6 or unaffected siblings7. Moreover, family functioning is more problematic in children with ADHD who have comorbid oppositional and conduct problems1. Consistent with this, negative EE has been associated with comorbid behavior problems in children with ADHD7–10. However, it is unclear whether negative EE is driven by comorbid externalizing behaviors or by ADHD per se3,11,12.

So far, most research has focused on a parent effect model as an explanation for the association between EE and child psychopathology13–15. That is, it is assumed that negative EE aggravates the course of child psychopathology (symptoms) over time. However, the reverse has also been considered7,16, i.e., high levels of parental critical EE could be a consequence rather than a determinant of behavior problems of a child. Raising a child with ADHD is associated with increased parenting stress and could easily lead to feelings of frustration and irritability in the parents who, in turn, negatively express these feelings towards their child1. In line with this, it has been argued that negative parenting starts as a reaction to the ADHD behavior of children. Subsequently, negative parenting increases the possibility of developing oppositional behaviors in children with ADHD17,18. This in turn may enhance negative parenting, causing a negative spiral of child behavior affecting parenting and parenting affecting child behavior.

Parental psychopathology could play an important role in the negative emotions parents express towards their children. Parents of children with ADHD have higher rates of psychopathology19,20 and parental ADHD and depression have been found to be associated with negative EE4,7,21–23. For parental ADHD the relation might be more complex as one study found parental response to children with high ADHD symptoms was more positive when mothers also had high ADHD symptoms17. Hence ADHD could even be a ‘protective’ factor for parental EE, when parental ADHD is considered in the relationship.

To shed light on the direction of effect between parental EE and child externalizing psychopathology one needs family studies that use a multilevel approach thereby teasing apart family and child effects, or longitudinal designs. Few studies have done so, with mixed results regarding the direction of effects. One study reported both child and family effects on parental EE, depending on the statistical approach used7,23. As for longitudinal studies, some revealed EE was predictive of later psychopathology over and beyond the predictive effect of baseline child psychopathology11,18,24. However these studies did not measure EE at follow-up; therefore, a bidirectional relationship between EE and child psychopathology cannot be ruled out. Of the studies that did involve follow-up measures of EE, one found preschool EE predicted ADHD diagnosis 4 years later12, a second did not reveal longitudinal associations between EE and externalizing behavior over a period of 2 years25, and a third showed child externalizing behavior predicted maternal EE in the subsequent year16. Longitudinal studies also reveal mixed results concerning the stability of EE12,16,25,26. Studies that have assessed the psychometric properties of EE measures like the Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) and Camberwell Family Interview (CFI) have suggested a low stability of EE over periods of 6 months or longer in parents of young children2. Moreover, none of the longitudinal studies used a clinical ADHD sample, leaving the association and direction of the relationship underinvestigated in children with ADHD.

In this 6-year follow-up study on children with an ADHD combined subtype diagnosis, we set out to investigate (a) the relationship between maternal EE and child psychopathology above the possible role of maternal psychopathology; (b) whether maternal EE is a risk factor for later externalizing behavior problems or vice versa, child externalizing behavior a risk factor for negative maternal EE; and (c) whether maternal EE remains stable over time.

Method

Participants

From 2003 to 2006 participants were recruited through child psychiatric clinics in the Netherlands as part of the International Multicenter ADHD Genetics (IMAGE) study27,28. Families were included in IMAGE if they had at least 1 child with an ADHD combined diagnosis (proband) and at least one additional sibling (regardless of gender or ADHD diagnosis). All children were Caucasians of European descent, between 5–19 years, had an IQ≥70, and no diagnosis of autism, epilepsy, general learning difficulties, brain disorders, or known genetic disorders (such as fragile X or Down syndrome). For the follow-up measurement, all family members were re-invited, with a mean follow-up period of 5.9 years (SD=.72) (see www.neuroimage.nl, for a description of the study). In this study 385 participants (from 270 families with one affected child and 54 families with 2 or more affected children) with an ADHD combined subtype diagnosis and a measurement of EE were included at baseline, of which data on 285 participants (from 212 families with one affected child and 33 families with two or more affected children) were available at follow-up. At follow-up 83.9% of the participants still had a diagnosis of ADHD (50.2% Combined, 41.0% Inattentive, and 8.8% Hyperactive/Impulsive subtype). Informed consent was signed by all participants at both time points (parents signed informed consent for participants under 12 years of age), and the study was approved by the ethical committee (Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek).

Diagnostic Assessment

At baseline screening questionnaires filled in by parents and teachers (long versions of the Conner’s rating scales; [CPRS-R:L] and [CTRS-R:L]29, and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ]30) and a semistructured, standardized, investigator-based interview (Parental Account of Children’s Symptoms [PACS]31,32) were used in a standardized algorithm to identify children with ADHD symptoms33. A clinical diagnosis was present for probands before inclusion. When probands and siblings screened positive, diagnostic interviews were conducted. A more detailed description of the screening procedure and ADHD phenotyping is provided by Brookes et al.32

At follow-up a standardized algorithm was applied again to a combination of a parent-rated questionnaire (CPRS-R:L34) and either a teacher-rating (CTRS-R:L35; applied for participants <18 years) or a self-report (Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating scales–Self Report: Long Version [CAARS-S:L]36 applied for participants ≥18 years), and the Dutch translation of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version37, carried out by trained professionals. For an in-depth description of the diagnostic algorithm, see www.neuroimage.nl.

Measures

Child Psychopathology

Dimensional ratings of child psychopathology were obtained at each time point. At both baseline and follow-up the Dutch CPRS-R:L was used to assess ADHD severity and oppositional problems in children (i.e., T-scores of scale N and scale A of the CPRS-R:L respectively34). Conduct problems were assessed at both time points by means of the conduct problems scale of the Dutch SDQ completed by parents38.

Parental Expressed Emotion

At both time points parental expressed criticism and warmth were assessed during the structured clinical interviews (i.e., PACS at baseline; K-SADS at follow-up), using codings derived from the Camberwell Family Interview39. As the data of fathers were far less complete, we only used the ratings of mothers in this study. Warmth was assessed by the tone of voice, spontaneity, sympathy, and/or empathy toward the child. Scores ranged from 0 (little warmth) to 3 (a great deal of expressed warmth)9. Criticism was assessed by statements which criticized or found fault with the child based on tone of voice and critical phrases. Scores on criticism ranged from 0 (no expressed criticism) to 4 (a lot of expressed criticism)9. The inter-rater reliability has been found to be adequate using similar codings for warmth and criticism (ranging from .78–.91 and .79–.86 respectively)40. At baseline an average agreement percentage of 96.6% (range 78.6–100) and a mean Kappa coefficient of .88 (range .71–1.00) were obtained across all sites for the total PACS, including the EE ratings41.

Parental Psychopathology

At baseline maternal ADHD problems were assessed by the Dutch ADHD self-report questionnaire42. At follow-up ADHD problems were measured by the Dutch version of Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale–Self-Report: Short Version [CAARS-S:S]43. For both questionnaires all item scores were summarized into a total score and then transformed into a z-score. To assess maternal affective problems (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety), the 12 and 28 item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)44 were used at baseline. A subsample of 105 mothers completed the GHQ-12 and 99 mothers completed the GHQ-28. A 4-point likert scoring was used on the items to generate total scores which were subsequently transformed into z-scores. At follow-up, maternal affective problems were measured by the Dutch version of the Kessler-10 (K10)45. Standardized total scores were calculated after applying a 5-point likert scoring to the items.

Missing Data

At baseline less than 5% of the data were missing for the child conduct problems, maternal criticism and maternal ADHD measures. Maternal affective problems were assessed in a subsample of 236 participants (38.7% missing). At follow-up, data were missing for less than 5% for the child ADHD, oppositional, and maternal ADHD measures. For the maternal affective problems measure 6.7% of the data were missing, for the maternal EE measure 18.3% were missing and for the child conduct problems measure 23.9% were missing. All missing data were replaced using multiple imputations (see data analyses section). Of the 385 children that were included at baseline, 74.0% (n =285) participated at follow-up. These children did not differ significantly from the children who did not participate at follow-up on maternal EE, age, ADHD, oppositional, or conduct problems (p>.141). This suggests that the sample in the follow-up study was representative of the initial study sample.

Data Analyses

Pearson correlation analyses were calculated to investigate the stability of maternal EE over time. Generalized estimated equations (GEE) with a linear regression model and robust estimators were used to test for an association between maternal EE and child psychopathology. Family number was used as repeated measure and the structure for working correlation matrices was set to exchangeable, to correct for the familial dependency within the sample.

First, for both time points, cross-sectional analyses were carried out separately for ADHD, oppositional, and conduct problems. The following potential predictors of child psychopathology were assessed: age, gender, ADHD medication use of the child, EE, maternal affective problems, and maternal ADHD problems. Because maternal warmth and criticism were correlated (but not strong enough to create one variable; r=−.49 at baseline and r=−.50 at follow-up), they were investigated separately in each analysis. Second, longitudinal analyses were performed with the baseline measures as potential predictors (i.e., age, gender, ADHD medication use, and psychopathology of children; and affective problems, ADHD problems, and EE of mothers) of child psychopathology at follow-up. Third, longitudinal analyses were carried out with the baseline child and follow-up maternal measures as potential predictors of maternal EE at follow-up.

P values are reported based on the pooled results of 10 imputations. A False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was employed to correct for multiple comparisons using a q-value of 0.0546. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Science, version 20.0.

Results

Child and Maternal Psychopathology

Table 1 shows the participant characteristics at baseline and follow-up. Child ADHD, oppositional, and conduct problems scores were significantly lower at follow-up than at baseline (p <.001). At each time point, measures of child psychopathology were significantly correlated with each other (table 2). In addition, child psychopathology scores were positively correlated over time (table 3). Likewise, maternal ADHD and affective problems were significantly correlated with each other at both time points and over time. Maternal ADHD problems had the highest stability (r=.67; table 3).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline (T1) and Follow-Up (T2)

| T1 | T2 | Pairwise

time comparison (p ≤.001) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n =385 | n = 285 | ||||||

| M | SE | Range | M | SE | Range | ||

| Child characteristics | |||||||

| Male, % | 83.40 | 83.50 | |||||

| ADHD diagnosis, % | 100.00 | 83.86 | |||||

| ADHD Medication use, % | 87.00 | 91.23 | |||||

| Age | 11.51 | .14 | 5.4–18.0 | 17.50 | .16 | 10.9–24.5 | |

| Child psychopathology | |||||||

| ADHD severity | 76.31 | .47 | 45–90 | 69.08 | .81 | 40–90 | T1 > T2 |

| Oppositional problems | 67.28 | .61 | 40–90 | 60.00 | .74 | 40–90 | T1 > T2 |

| Conduct problems | 4.03 | .12 | 0–10 | 2.94 | .15 | 0–10 | T1 > T2 |

| Parental Expressed Emotion | |||||||

| MEE warmth | 1.46 | .05 | 0–3 | 1.52 | .06 | 0–3 | T1 = T2 |

| MEE criticism | 1.81 | .05 | 0–4 | 1.77 | .06 | 0–4 | T1 = T2 |

| Parental psychopathology | |||||||

| Maternal ADHD problems | .00 | .05 | −1.3 to 3.1 | .00 | .06 | −1.3 to 3.7 | |

| Maternal affective problems | .01 | .06 | −2.3 to 3.4 | .00 | .06 | −1.3 to 4.5 | |

Note: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis of children at follow-up included Combined, Inattentive, and Hyperactive/ Impulsive subtype. Z-scores are displayed for maternal ADHD and affective problems. MEE = maternal expressed emotion.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Maternal Expressed Emotion (MEE), Child Psychopathology, and Maternal Psychopathology Separate for Baseline and Follow-Up

| Measure | MEE warmth |

MEE criticism |

ADHD severity |

Oppositional problems |

Conduct problems |

Maternal ADHD problems |

Maternal Affective problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEE warmth | × | −.51** | −.06 | −.12 | −.14 | .02 | .04 |

| MEE criticism | −.51** | × | .14 | .25** | .17* | .04 | .03 |

| ADHD severity | −.15** | .09 | × | .64** | .49** | .34** | .26** |

| Oppositional problems | −.03 | .04 | .44** | × | .70** | .31** | .25** |

| Conduct problems | −.05 | .07 | .28** | .66** | × | .15** | .19* |

| Maternal ADHD problems | −.05 | .06 | .20** | .24** | .16** | × | .67** |

| Maternal affective problems | −.02 | .07 | .12* | .11 | .07 | .22** | × |

Note: Correlations with MEE and child psychopathology were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient, correlations with maternal psychopathology using Spearman correlation coefficient. Numbers under the diagonal represent correlations at baseline; numbers above the diagonal represent the correlations at follow-up. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Significant at p≤.05

Significant at p≤.01

Table 3.

Correlations of Maternal Expressed Emotion (MEE), Child Psychopathology, and Maternal Psychopathology Between Baseline and Follow-Up

| T1 | T2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | MEE warmth |

MEE criticism |

ADHD severity |

Oppositional problems |

Conduct problems |

Maternal ADHD problems |

Maternal Affective problems |

| MEE warmth | .08 | −.14* | .00 | −.07 | .05 | −.00 | .03 |

| MEE criticism | −.04 | .06 | −.05 | .05 | −.04 | .05 | −.02 |

| ADHD severity | −.09 | .13* | .26** | .09 | .03 | .14* | .07 |

| Oppositional problems | −.09 | .15** | .26** | .46** | .32** | .27** | .25** |

| Conduct problems | −.13* | .13* | .20** | .40** | .43** | .14* | .21** |

| Maternal ADHD problems | −.03 | .05 | .27** | .17** | .08 | .67** | .51** |

| Maternal affective problems | −.03 | −.06 | .05 | .06 | .05 | .20** | .21** |

Note: Correlations with MEE and child psychopathology were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient, correlations with maternal psychopathology using Spearman correlation coefficient. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Significant at p≤.05

Significant at p≤.01

Stability of Maternal EE

Dependent T-tests revealed that, on average, the levels of maternal warmth and criticism did not differ significantly over time (Table 1). Maternal warmth and criticism were negatively correlated with each other, at both baseline and follow-up (Table 2). However, neither maternal warmth nor criticism proved to be stable over time, as was reflected by the absence of significant correlations between baseline and follow-up (Table 3). A small negative association was found between maternal warmth at baseline and criticism at follow-up.

Maternal EE and Child Psychopathology

Examining the cross-sectional correlations between EE, maternal psychopathology and child psychopathology (Table 2), maternal psychopathology and EE were found to be uncorrelated at both time points. All maternal and child psychopathology measures were associated with each other at both time points (p ≤.05), with exception of maternal affective problems and child oppositional and conduct problems at baseline. Furthermore, at baseline maternal warmth was negatively correlated with child ADHD severity (p ≤.01). At follow-up maternal criticism was significantly and positively related to child oppositional and conduct problems (p ≤.05). When looking at the longitudinal associations (Table 3), we found child psychopathology at baseline was slightly, but significantly, correlated with maternal criticism and maternal ADHD problems at follow-up (p ≤.05). Also, child oppositional and conduct problems at baseline were related to maternal affective problems at follow-up (p ≤.05). Only maternal ADHD at baseline was associated with child ADHD severity and oppositional problems at follow-up (p ≤.01).

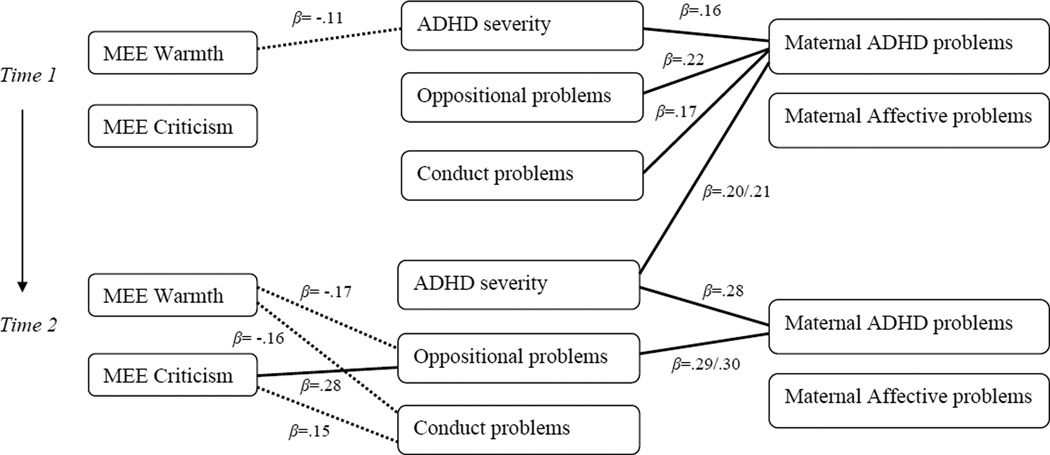

GEE linear regression analyses confirmed the cross-sectional correlations at baseline between maternal warmth and child ADHD severity (p ≤.05), and at follow-up between maternal criticism and child oppositional (p ≤.01) and conduct problems (p ≤.05; Figure 1 and Table S1, available online). In addition, nominally negative associations were found between maternal warmth and child oppositional and conduct problems at follow-up (p ≤.05). As for the longitudinal analyses, again only maternal ADHD problems at baseline predicted child ADHD severity at follow-up, when corrected for baseline child ADHD severity (p ≤.01; Figure 1 and Table S2, available online). Finally, child psychopathology at baseline did not significantly predict maternal warmth or criticism at follow-up (Table S3, available online).

Figure 1.

Overview of the significant and nominally significant associations (expressed as Beta-values) between maternal expressed emotion, child psychopathology and maternal psychopathology at baseline and follow-up. Note: The undotted lines represent significant associations after correction for multiple testing (p≤.01); the dotted lines nominally significant associations (p≤.05). ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; MEE = maternal expressed emotion.

Discussion

We investigated the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between maternal EE and the severity of ADHD, oppositional and conduct problems in children with an ADHD combined subtype diagnosis. The possible influencing role of maternal psychopathology was considered in these analyses. Measuring EE at two time points allowed us to not only examine the effects of maternal EE on child behavior, but also of child behavior on maternal EE. Finally, the design allowed us to study the stability of EE across time.

The results showed that, over a period of 6 years, maternal EE is not stable. The instability of EE over this period of time, which is longer than in previous studies, appears nonetheless congruent with the literature2. Next, we found different cross-sectional associations between EE and child psychopathology at each time point. At baseline, higher maternal warmth was linked with less severe ADHD of the child, whereas at follow-up, more maternal criticism was associated with more child oppositional and conduct problems and more maternal warmth with less child oppositional and conduct problems. However, our analyses did not reveal any longitudinal predictions for child psychopathology at follow-up from EE at baseline, or vice versa, for EE at follow-up from child psychopathology at baseline. Our findings are in line with a study on children with Intellectual Disability, in which cross-sectional, but no longitudinal associations between parental EE and child externalizing behavior were found25. Two studies that did find longitudinal predictions between EE and child externalizing psychopathology point in different directions; one supporting a child effect model16 and the other a parent effect model12. However, these studies both used community samples rather than an ADHD sample, making the results difficult to compare. Finally, maternal psychopathology did not play a significant role in the associations between EE and child psychopathology in the present study. This indicates that maternal EE is associated with child psychopathology above maternal psychopathology, which is in line with previous literature4.

An explanation for our different findings being significant cross-sectionally, but not longitudinally, can be provided by a developmental psychopathology perspective. This perspective emphasizes that next to continuous stressors with stable effects, each developmental stage comes with different vulnerabilities to specific influences and also provides new challenges for parents of children with ADHD1. When children are younger, parents might be able to handle or accept more negative behavior, but when children reach adolescence and beyond, parents expect better behavior and therefore are more critical. This could explain why at baseline maternal warmth was associated with child ADHD severity, while at follow-up maternal criticism was related to child oppositional and conduct problems. In this way our findings reflect the ability of parents to cope with and react to their children’s behavior at different developmental stages in different ways. This also fits with the fact that EE appears not to be a stable factor over time.

A related theory is that at first negative parenting is a reaction to children’s ADHD behavior. Subsequently, negative parenting increases the possibility of developing oppositional problems17,18. This, however, does not fit with the fact that we did not find any predictions of child oppositional or conduct problems at follow-up from EE at baseline. It is still possible that this negative spiral of child behavior affecting parenting, and parenting affecting child behavior is a relevant mechanism over shorter time intervals but not over a longer period of 6 years.

To further complicate the matter, some children might be more genetically susceptible to parental EE than others. The differential susceptibility theory is a quite new perspective on GxE interactions, which states that children carrying risk variants of so called plasticity genes, will be more at disadvantage in negative, but conversely, more at advantage in positive environments47,48. In fact, associations of maternal EE and comorbid conduct problems in children with ADHD have been found to be moderated by variants of plasticity genes9. Including the genetic vulnerability of children could shed new light on the results presented in this paper.

This study had a number of strengths and possible limitations. Strengths of this study were the well characterized clinical sample and use of longitudinal follow-up measurements with structured instruments. A possible limitation was the use of different questionnaires to assess maternal psychopathology; ideally the same measurements should be used over time as was done with the children’s measurements. Next, our analyses were based on maternal EE. Future studies might include measures of paternal EE and examine the separate and combined effects of both paternal and maternal EE. Furthermore, while teacher and/or self ratings were obtained in the study, we included only parent ratings of child psychopathology in the analyses, because these parental data were more complete. Though past research has shown similar associations between parental EE and child psychopathology over multiple informants9, future work might also include teacher and child self-report on ADHD and problem behavior to address potential rater bias. Finally, in this study we focused on children with an ADHD combined subtype diagnosis. It would be interesting to examine if the same associations are found in children with other ADHD subtypes.

With respect to the clinical implications, the results of our study do not support targeting family-based interventions on modifying levels of parental EE in order to reduce externalizing behavior problems in children with an ADHD diagnosis. However it would be premature to conclude that parenting and family-based interventions lack an evidence-base overall. For these interventions focus on a range of factors, including the structure and rule-setting of families, rather than EE alone. Studies investigating the effects of parent training on child externalizing behavior have found evidence for its success49–51.

To conclude, our results support previous findings of cross-sectional associations between parental EE and child psychopathology, though these associations were not stable over time. These results, together with the finding that EE was not stable over 6 years, suggest that EE is a momentary state measure varying with contextual factors including the child’s psychiatric problems and developmental phase rather than a stable trait or attitude. EE does not appear to be a risk factor for later severity of externalizing behavior in children with ADHD. As 6 years is quite a long period in child development, it could be further investigated if EE does remain stable for shorter periods of time in children with ADHD by including more frequent measurements of EE (e.g., every couple of months). In addition, future research may use multiple instruments as questionnaires and interviews to assess parental EE and examine whether genetic vulnerability or plasticity genes in the child moderate the influences of EE on the severity (and course) of child psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01MH62873, the Netherlands Science Foundation (NWO) Large Investment grant 1750102007010 (J.K.B.), and grants from Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen, University Medical Center Groningen and Accare, and VU University Amsterdam.

The authors thank all the families who participated in this study and also the researchers who collected the data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Dr. Oosterlaan has received an unrestricted investigator initiated research from Shire. In the past 2 years, Dr. Buitelaar has been a consultant to / member of advisory board of / and/or speaker for Janssen Cilag BV, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Shering Plough, UCB, Shire, Novartis and Servier. He is not an employee of any of these companies, and not a stock shareholder of any of these companies. He has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents, and royalties. Dr. Hoekstra has been a member of the advisory board of and has received research funding from Shire in the past two years. Ms. Richards, and Drs. Arias Vásquez, Rommelse, Franke and Hartman report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jennifer S. Richards, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Alejandro Arias Vásquez, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Nanda N.J. Rommelse, Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Jaap Oosterlaan, Vrije Universiteit (VU) Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Pieter J. Hoekstra, University Medical Centre Groningen, University of Groningen, the Netherlands

Barbara Franke, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Catharina A. Hartman, University Medical Centre Groningen, University of Groningen, the Netherlands

Jan K. Buitelaar, Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

References

- 1.Deault LC. A systematic review of parenting in relation to the development of comorbidities and functional impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Child psychiatry and human development. 2010;41(2):168–192. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley D, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Thompson M. Assessing expressed emotion in mothers of preschool AD/HD children: psychometric properties of a modified speech sample. The British journal of clinical psychology / the British Psychological Society. 2003;42(Pt 1):53–67. doi: 10.1348/014466503762842011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psychogiou L, Daley DM, Thompson MJ, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Mothers’ expressed emotion toward their school-aged sons. Associations with child and maternal symptoms of psychopathology. European child and adolescent psychiatry. 2007;16(7):458–464. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0619-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peris TS, Hinshaw SP. Family dynamics and preadolescent girls with ADHD: the relationship between expressed emotion, ADHD symptomatology, and comorbid disruptive behavior. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2003;44(8):1177–1190. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cussen A, Sciberras E, Ukoumunne OC, Efron D. Relationship between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and family functioning: a community-based study. European journal of pediatrics. 2012;171(2):271–280. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keown L. Fathering and mothering of preschool boys with hyperactivity. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;35(2):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartwright KL, Bitsakou P, Daley D, et al. Disentangling child and family influences on maternal expressed emotion toward children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):1042–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ, Judice S. Family correlates of oppositional and conduct disorders in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2005;33(5):551–563. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Oades RD, Psychogiou L, et al. Dopamine and serotonin transporter genotypes moderate sensitivity to maternal expressed emotion: the case of conduct and emotional problems in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2009;50(9):1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Lasky-Su J, Neale BM, et al. Does parental expressed emotion moderate genetic effects in ADHD? An exploration using a genome wide association scan. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B(8):1359–1368. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keown LJ. Predictors of boys’ ADHD symptoms from early to middle childhood: the role of father-child and mother-child interactions. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2012;40(4):569–581. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peris TS, Baker BL. Applications of the expressed emotion construct to young children with externalizing behavior: stability and prediction over time. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2000;41(4):457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asarnow JR, Tompson M, Hamilton EB, Goldstein MJ, Guthrie D. Family-expressed emotion, childhood-onset depression, and childhood-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders: is expressed emotion a nonspecific correlate of child psychopathology or a specific risk factor for depression? Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1994;22(2):129–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02167896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirshfeld DR, Biederman J, Brody L, Faraone SV, Rosenbaum JF. Associations between expressed emotion and child behavioral inhibition and psychopathology: a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199702000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz CE, Dorer DJ, Beardslee WR, Lavori PW, Keller MB. Maternal expressed emotion and parental affective disorder: risk for childhood depressive disorder, substance abuse, or conduct disorder. Journal of psychiatric research. 1990;24(3):231–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90013-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale WW, Keijsers L, Klimstra TA, et al. How does longitudinally measured maternal expressed emotion affect internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents from the general community? Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2011;52(11):1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psychogiou L, Daley DM, Thompson MJ, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Do maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms exacerbate or ameliorate the negative effect of child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms on parenting? Development and psychopathology. 2008;20(1):121–137. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor E, Chadwick O, Heptinstall E, Danckaerts M. Hyperactivity and conduct problems as risk factors for adolescent development. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(9):1213–1226. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margari F, Craig F, Petruzzelli MG, Lamanna A, Matera E, Margari L. Parents psychopathology of children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Research in developmental disabilities. 2013;34(3):1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biederman J. Family-Environment Risk Factors for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Test of Rutter’s Indicators of Adversity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(6):464. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovejoy MC, Graczyk Pa, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a metaanalytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster CJE, Garber J, Durlak JA. Current and past maternal depression, maternal interaction behaviors, and children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2008;36(4):527–537. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonuga-Barke EJS, Cartwright KL, Thompson MJ, et al. Family characteristics, expressed emotion, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(5):547–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loeber R, Hipwell A, Battista D, Sembower M, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Intergenerational transmission of multiple problem behaviors: prospective relationships between mothers and daughters. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2009;37(8):1035–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9337-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C, Beck A. Maternal distress and expressed emotion: cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American journal of mental retardation. 2006;111(1):48–61. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[48:MDAEEC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bird HR, Shrout PE, Duarte CS, Shen S, Bauermeister JJ, Canino G. Longitudinal mental health service and medication use for ADHD among Puerto Rican youth in two contexts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):879–889. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179963c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller UC, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, et al. The impact of study design and diagnostic approach in a large multi-centre ADHD study: Part 2: Dimensional measures of psychopathology and intelligence. BMC psychiatry. 2011;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller UC, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, et al. The impact of study design and diagnostic approach in a large multi-centre ADHD study. Part 1: ADHD symptom patterns. BMC psychiatry. 2011;11(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conners CK. Rating scales in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: use in assessment and treatment monitoring. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor E. Childhood hyperactivity. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149(5):562–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Molecular psychiatry. 2006;11(10):934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rommelse NNJ, Oosterlaan J, Buitelaar J, Faraone SV, Sergeant JA. Time reproduction in children with ADHD and their nonaffected siblings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(5):582–590. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3180335af7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1998;26(4):257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. Revision and restandardization of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1998;26(4):279–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1022606501530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conners CK, Erhardt D, Sparrow EP. Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales: CAARS. North Tonowanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, Treffers PDa, Goodman R. Dutch version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) European child and adolescent psychiatry. 2003;12(6):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown GW. The Measurement of Family Activities and Relationships: A Methodological Study. Human Relations. 1966;19(3):241–263. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schachar R, Taylor E, Wieselberg M, Thorley G, Rutter M. Changes in family function and relationships in children who respond to methylphenidate. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26(5):728–732. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen W, Taylor E. PACS interview and genetic research in ADHD. In: Oades R, editor. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder HKS: Current ideas and ways forward. 1st ed. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2006. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kooij JJS, Buitelaar JK, van den Oord EJ, Furer JW, Rijnders CA, Hodiamont PPG. Internal and external validity of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(6):817–827. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400337x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conners CK, Erhardt D, Epstein JN, Parker JDa, Sitarenios G, Sparrow E. Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults I: Factor structure and normative data. Journal of Attention Disorders. 1999;3(3):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koeter MWJ, Ormel J. General Health Questionnaire, Nederlandse bewerking: handleiding. Lisse: Swets, Test Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donker T, Comijs H, Cuijpers P, et al. The validity of the Dutch K10 and extended K10 screening scales for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry research. 2010;176(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis B, Boyce W. Differential susceptibility to the environment: Toward an understanding of sensitivity to developmental experiences and context. Development and psychopathology. 2011;23(1):1–5. doi: 10.1017/S095457941000060X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, Hutchings J, Smith SM, Donnelly M. Cochrane Review: Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years (Review) The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2. CD008225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwi M, Jones H, Thorgaard C, York A, Dennis JA. Parent training interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;(12) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003018.pub3. CD003018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton SS, Armando J. Oppositional defiant disorder. American family physician. 2008;78(7):861–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.