Abstract

Epigenetic processes play a key role in the central nervous system and altered levels of 5-methylcytosine have been associated with a number of neurological phenotypes, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Recently three additional cytosine modifications have been identified (5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine), which are thought to be intermediate steps in the demethylation of 5-methylcytosine to unmodified cytosine. Little is known about the frequency of these modifications in the human brain during health or disease. In this study we used immunofluorescence to confirm the presence of each modification in human brain and investigate their cross-tissue abundance in Alzheimer’s disease patients and elderly control samples. We identify a significant AD-associated decrease in global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in entorhinal cortex and cerebellum, and differences in 5-formylcytosine levels between brain regions. Our study further implicates a role for epigenetic alterations in AD.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, Brain, 5-methylcytosine, 5-mC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-hmC, 5-formylcytosine, 5-fC, 5-carboxylcytosine, 5-caC, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease affecting >5.4 million adults in the US and contributing significantly to the global burden of disease (Thies and Bleiler, 2011). Given the high heritability estimates for AD (Gatz, et al., 2006), considerable effort has focussed on understanding the role of genetic variation in disease etiology, although it has been recently speculated that epigenetic dysfunction is also likely to be important (Lunnon and Mill, 2013).

Epigenetics refers to the reversible regulation of various genomic functions occurring independently of DNA sequence, with cytosine methylation being the best understood and most stable epigenetic modification modulating the transcription of mammalian genomes. Recent studies have identified global- and site-specific alterations in 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) levels in AD brain (Bakulski, et al., 2012, Mastroeni, et al., 2010, Mastroeni, et al., 2009, Rao, et al., 2012).

A number of additional cytosine modifications have recently been described. 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) has been shown to be enriched in brain (Khare, et al., 2012), suggesting it may play an important role in neurobiological phenotypes and disease. Importantly, current approaches based on sodium bisulfite converted DNA are unable to distinguish between 5-mC and 5-hmC (Nestor, et al., 2010). 5-hmC is believed to be an intermediate step in the demethylation of 5-mC to unmodified cytosine by the oxidation of 5-mC by ten eleven translocation (TET) proteins (Tahiliani, et al., 2009). 5-hmC is thought to play a specific role in transcriptional regulation as it is recognised by key proteins that do not recognise 5-mC (Jin, et al., 2010), has a distinct genomic distribution to 5-mC (being predominantly found in gene promoters and gene bodies and rarely in intergenic regions (Jin, et al., 2011,Stroud, et al., 2011)), is more abundant in constitutive exons than alternatively spliced ones (Khare, et al., 2012) and has a lower affinity to methyl-binding proteins than 5-mC (Hashimoto, et al., 2012). 5-hmC appears to be present in all tissues, although at differing levels, with the highest levels observed in brain (Li and Liu, 2011) with enrichment in genes involved in synapse-related functions (Khare, et al., 2012); in contrast the distribution of 5-mC appears to be relatively uniform across tissues (Globisch, et al., 2010). It has been suggested that while some hydroxymethylated-CpG loci are stable during aging, others are more dynamically altered (Szulwach, et al., 2011).

In 2011, two additional cytosine modifications were described in mouse embryonic stem cells and somatic tissues (Inoue, et al., 2011,Ito, et al., 2011). 5-formylcytosine (5-fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC) were found to result from the further oxidation of 5-hmC by TET proteins (Ito, et al., 2011), suggesting that these modifications represent further steps along the demethylation pathway (Inoue, et al., 2011). Although little is known about their functional role and prevalence in the healthy genome, recent studies have mapped 5-fC to gene regulatory elements, namely poised enhancers and CpG island promoters (Raiber, et al., 2012,Song, et al., 2013).

The aim of the current study was to investigate the relative abundance of the four described cytosine modifications across two distinct anatomical brain regions (entorhinal cortex (EC) and cerebellum (CER)) in tissue obtained from AD cases and elderly controls.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects and Sample Preparation

Formalin-fixed tissue punches from the EC and CER were obtained from AD cases (n=13) and cognitively normal elderly control (CTL) subjects (n=8) from the MRC London Neurodegenerative Diseases Brain Bank (http://www.kcl.ac.uk/iop/depts/cn/research/MRC-London-Neurodegenerative-Diseases-Brain-Bank/MRC-London-Neurodegenerative-Diseases-Brain-Bank.aspx). Sample demographics are shown in Table S1.

2.2 Immunofluorescence

Samples were cryosectioned at 10μm on a freezing Cryostat before immunostaining with antibodies purchased from Active Motif against 5-mC (Cat# 39649), 5-hmC (Cat# 39791), 5-caC (Cat# 61225) and 5-fC (Cat# 61223). Briefly following antigen retrieval (10mM sodium citrate, 0.05% tween, pH6.0, 80°C), quenching of endogenous immunofluorescence (300mM glycine) and membrane permeabilisation (Triton-X), non-specific binding was blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes prior to the addition of primary antibody (1:2000 dilution in 5% NGS for 16 hours at 4°C). Slides were incubated with biotinylated goat secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) at 1:200 dilution for 1 hour, followed by streptavidin-AF596 (Life Technologies) for 1 hour. To minimise auto-fluorescence samples were incubated with 0.3% Sudan Black for 30 minutes then mounted on coverslips with Prolong-Gold with DAPI (Life Technologies).

2.3 Microscopy and Analysis

Appropriate controls to demonstrate the specificity of antibodies were included for every sample, including a primary antibody control (incubation with the relevant nucleoside (Inoue, et al., 2011) prior to staining) and a secondary antibody control (incubation in the absence of primary antibody). Immunofluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Imager II at 40X magnification, with all camera and microscope settings constant for all images taken within each antibody. The two control sections were checked by eye for each slide followed by the capture of 10 images from non-overlapping fields of view taken from each of two stained sections. Images were analysed using an ImageJ script to determine the level of fluorescence per positive cell that applied a threshold pixel value to the red (AF546) channel to create a binary mask image, which was then used as a template for measuring the red fluorescence. A binary mask was used as it allowed the measurement of fluorescence only within the nuclei and removed any non-specific background staining from the analysis. We then calculated the intensity within each nuclei staining positive in a given image and generated an average per cell by dividing the total fluorescence intensity in the binary mask of a given image by the number of nuclei staining positive in that image. This was then averaged across the 10 images. Data was assessed for normality and analyzed first using mixed effects modelling in STATA (StataCorp) to identify differences between AD cases and controls across each brain region, while controlling for age and gender. When an association with disease was observed we employed linear modelling to look for differences associated with Braak score, a measure of disease stage (Braak and Braak, 1991) whilst controlling for age and gender.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Each cytosine modification is present in adult human brain

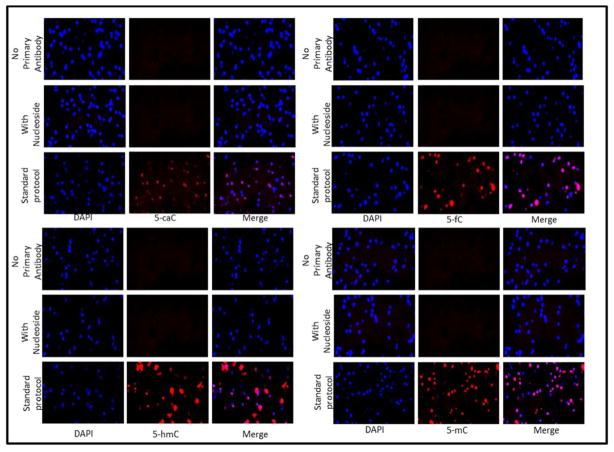

Initially we sought to investigate whether each of the four cytosine modifications could be detected in adult human brain. Because two of the antibodies (5-fC and 5-caC) had yet to be tested in human samples, we first stained sections of human EC with antibodies specific to each modification (Fig 1). Staining of all four antibodies co-localised with DAPI confirming nuclear staining. To test for non-specific staining, each antibody was incubated with its complimentary nucleoside prior to staining to act as a negative control. As expected no staining was observed, demonstrating the specificity of the antibodies. Similarly no staining was observed in the absence of the primary antibody. Once we had established the specificity of the antibodies and the presence of each cytosine modification in human brain we compared their relative abundance in two distinct anatomical brain regions and whether different levels are present in AD cases compared to controls (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Immunofluorescence demonstrating the specificity of the antibodies used in this study. At the concentrations used no staining was observed in either the no primary antibody control, or the nucleoside control. Staining of tissue (in absence of controls) was co-localised with DAPI, demonstrating nuclear staining.

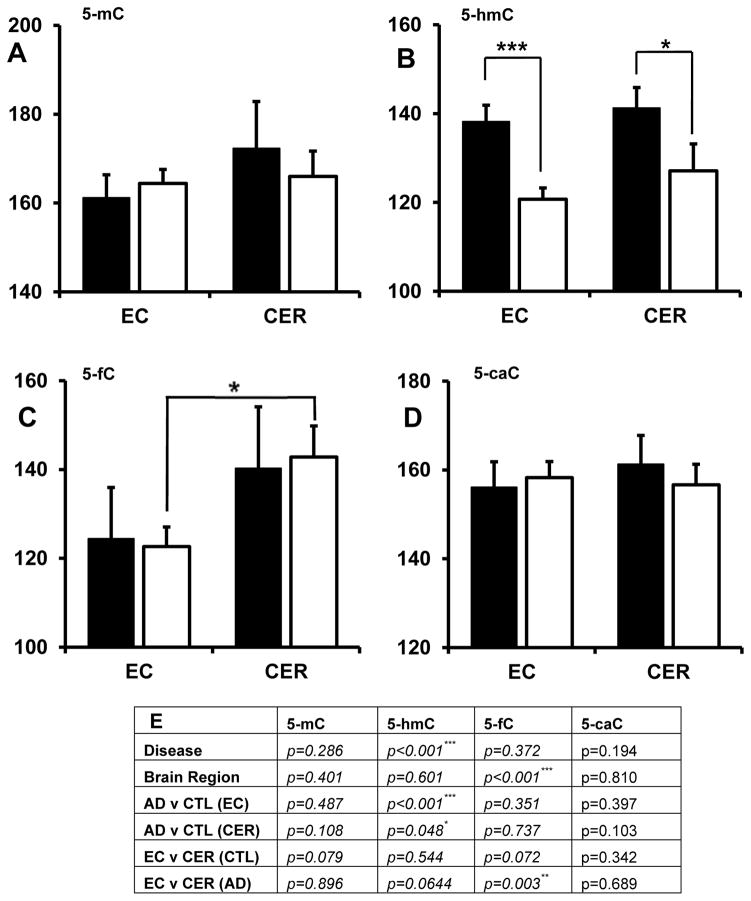

Fig 2.

Differences in nuclear fluorescence intensity for each cytosine modification in tissue from control (black) and AD (white) brains. Data is represented as the mean fluorescence per positive cell across all samples in the group (±SEM). (A) There was no difference in 5-mC levels in AD samples, or across brain regions.(B) There was an overall effect of disease on 5-hmC levels (p<0.001), with a decrease in 5-hmC in AD samples compared to control in both the EC (p<0.001) and CER (p=0.0476) (C) There was a significant effect of brain region on 5-fC levels (p<0.001), with a significant difference in 5-fC in EC compared to CER in AD (p=0.0026) (C). There was no difference in 5-caC in AD samples, or across brain regions (D). Between groups p-values are tabulated (E).

3.2 Cross-tissue differences in 5-mC in AD

Recent studies have demonstrated differential DNA methylation at specific loci between EC and CER (Davies, et al., 2012) and between AD and controls. Here, we found no significant difference in global 5-mC level between brain regions (p=0.286) nor in disease (p=0.401) (Fig 2A). Similarly two previous studies have also demonstrated no difference in 5-mC in CER in AD (Mastroeni, et al., 2010, Mastroeni, et al., 2009), however one of these studies showed decreased 5-mC in AD EC (Mastroeni, et al., 2010). Discrepancies between that study and our own could be due to a number of technical issues, including different reagents, fewer samples within our study, different sample cohorts and perimortem differences such as post-mortem delay (PMD) and brain pH, where their influence on DNA methylation are currently unknown (Pidsley and Mill, 2011).

3.3 Cross-tissue differences in 5-hmC in AD

We found an overall significant effect of disease status (p<0.001) but not brain region (p=0.061) on 5-hmC levels, with a significant decrease in 5-hmC in AD compared to control in both EC (p<0.001) and CER (p=0.0476) (Fig 2B). We also observed a significant negative correlation between global 5-hmC and Braak score, a measure of AD neuropathology and disease stage, in both the EC (r=0.6927, p<0.001) and CER (r=0.2795, p=0.029). Our findings indicate that there is a global reduction in 5-hmC in AD brain that is present in both regions of primary neuropathology (EC) and regions largely devoid of neuropathology (CER), suggesting a potential global response to the disease process. Our results also concur with a recent study by Chouliaras et al that identified AD- and neuropathology-associated reductions in glial 5-hmC in the hippocampus and in the affected sib of a monozygotic twin pair discordant for AD (Chouliaras, et al., 2013).

3.4 Cross-tissue differences in 5-fC and 5-caC in AD

We found an overall significant effect of brain area (p<0.001), but not of disease (p=0.372) on 5-fC abundance, with significantly less 5-fC in EC than CER in AD (p=0.0026), and a near-significant reduction in controls (p=0.072) (Fig 2C). There was no significant effect of brain area (p=0.810), nor disease (p=0.194) on 5-caC levels (Fig 2D). Both 5-fC and 5-caC are reported to be present at 10–1000 fold lower levels than 5-hmC in primordial germ cells (Vincent, et al., 2013), accounting for between 3–20 parts per million cytosines across the genome (Song, et al., 2012).

Conclusions

This study confirmed that four cytosine modifications are present in adult human brain and that there is a significant reduction in 5-hmC in AD, across two different anatomical regions of the brain. These data concur with previous reports of an AD-associated reduction in 5-hmC in the hippocampus (Chouliaras, et al., 2013). Although there was a regional difference in 5-fC levels, no AD-associated changes in 5-mC, 5-fC, or 5-caC were observed, although previous reports have shown decrements in 5-mC in AD EC and hippocampus (Chouliaras, et al., 2013, Mastroeni, et al., 2010). Given the relatively small numbers of samples assessed in this study, further research investigating the specificity of the differences in 5-hmC and 5-fC we report, particularly across different neuron and glia subtypes, will be of particular interest to the field. Our observation has implications for current efforts to map site-specific changes in 5-mC in AD using bisulfite-based approaches that cannot distinguish between 5-mC and 5-hmC and suggests that disease-associated differentially methylated regions (DMRs) should be interrogated using approaches that can specifically target these modifications (e.g. oxidative-bisulfite sequencing (Booth, et al., 2012,Booth, et al., 2013).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant AG036039. We thank the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Dementia in the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Brains for Dementia Research and the donors and families who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in regard to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bakulski KM, Dolinoy DC, Sartor MA, Paulson HL, Konen JR, Lieberman AP, Albin RL, Hu H, Rozek LS. Genome-wide DNA methylation differences between late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal controls in human frontal cortex. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2012;29(3):571–88. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth MJ, Branco MR, Ficz G, Oxley D, Krueger F, Reik W, Balasubramanian S. Quantitative sequencing of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at single-base resolution. Science. 2012;336(6083):934–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1220671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth MJ, Ost TW, Beraldi D, Bell NM, Branco MR, Reik W, Balasubramanian S. Oxidative bisulfite sequencing of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nature protocols. 2013;8(10):1841–51. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaras L, Mastroeni D, Delvaux E, Grover A, Kenis G, Hof PR, Steinbusch HW, Coleman PD, Rutten BP, van den Hove DL. Consistent decrease in global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurobiology of aging. 2013;34(9):2091–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, Lunnon K, Dixit A, Lovestone S, Coarfa C, Harris RA, Milosavljevic A, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Dobson R, Schalkwyk LC, Mill J. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome biology. 2012;13(6):R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, Fiske A, Pedersen NL. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006;63(2):168–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globisch D, Munzel M, Muller M, Michalakis S, Wagner M, Koch S, Bruckl T, Biel M, Carell T. Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PloS one. 2010;5(12):e15367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Liu Y, Upadhyay AK, Chang Y, Howerton SB, Vertino PM, Zhang X, Cheng X. Recognition and potential mechanisms for replication and erasure of cytosine hydroxymethylation. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40(11):4841–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Shen L, Dai Q, He C, Zhang Y. Generation and replication-dependent dilution of 5fC and 5caC during mouse preimplantation development. Cell research. 2011;21(12):1670–6. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C, Zhang Y. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Kadam S, Pfeifer GP. Examination of the specificity of DNA methylation profiling techniques towards 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(11):e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Wu X, Li AX, Pfeifer GP. Genomic mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the human brain. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(12):5015–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare T, Pai S, Koncevicius K, Pal M, Kriukiene E, Liutkeviciute Z, Irimia M, Jia P, Ptak C, Xia M, Tice R, Tochigi M, Morera S, Nazarians A, Belsham D, Wong AH, Blencowe BJ, Wang SC, Kapranov P, Kustra R, Labrie V, Klimasauskas S, Petronis A. 5-hmC in the brain is abundant in synaptic genes and shows differences at the exon-intron boundary. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19(10):1037–43. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu M. Distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in different human tissues. Journal of nucleic acids. 2011;2011:870726. doi: 10.4061/2011/870726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunnon K, Mill J. Epigenetic studies in Alzheimer’s disease: current findings, caveats and considerations for future studies. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32201. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni D, Grover A, Delvaux E, Whiteside C, Coleman PD, Rogers J. Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer’s disease: decrements in DNA methylation. Neurobiology of aging. 2010;31(12):2025–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni D, McKee A, Grover A, Rogers J, Coleman PD. Epigenetic differences in cortical neurons from a pair of monozygotic twins discordant for Alzheimer’s disease. PloS one. 2009;4(8):e6617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor C, Ruzov A, Meehan R, Dunican D. Enzymatic approaches and bisulfite sequencing cannot distinguish between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in DNA. BioTechniques. 2010;48(4):317–9. doi: 10.2144/000113403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidsley R, Mill J. Epigenetic studies of psychosis: current findings, methodological approaches, and implications for postmortem research. Biological psychiatry. 2011;69(2):146–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiber EA, Beraldi D, Ficz G, Burgess H, Branco MR, Murat P, Oxley D, Booth MJ, Reik W, Balasubramanian S. Genome-wide distribution of 5-formylcytosine in ES cells is associated with transcription and depends on thymine DNA glycosylase. Genome biology. 2012;13(8):R69. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-8-r69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JS, Keleshian VL, Klein S, Rapoport SI. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer’s disease and bipolar disorder patients. Translational psychiatry. 2012;2:e132. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CX, Szulwach KE, Dai Q, Fu Y, Mao SQ, Lin L, Street C, Li Y, Poidevin M, Wu H, Gao J, Liu P, Li L, Xu GL, Jin P, He C. Genome-wide profiling of 5-formylcytosine reveals its roles in epigenetic priming. Cell. 2013;153(3):678–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CX, Yi C, He C. Mapping recently identified nucleotide variants in the genome and transcriptome. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30(11):1107–16. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud H, Feng S, Morey Kinney S, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is associated with enhancers and gene bodies in human embryonic stem cells. Genome biology. 2011;12(6):R54. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulwach KE, Li X, Li Y, Song CX, Wu H, Dai Q, Irier H, Upadhyay AK, Gearing M, Levey AI, Vasanthakumar A, Godley LA, Chang Q, Cheng X, He C, Jin P. 5-hmC-mediated epigenetic dynamics during postnatal neurodevelopment and aging. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14(12):1607–16. doi: 10.1038/nn.2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(2):208–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JJ, Huang Y, Chen PY, Feng S, Calvopina JH, Nee K, Lee SA, Le T, Yoon AJ, Faull K, Fan G, Rao A, Jacobsen SE, Pellegrini M, Clark AT. Stage-specific roles for tet1 and tet2 in DNA demethylation in primordial germ cells. Cell stem cell. 2013;12(4):470–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.