Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the optimal frequency of combined aerobic and resistance training for improving muscular strength (MS), cardiovascular fitness (CF), and functional tasks (FTs) in women older than 60 years. Sixty-three women were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 exercise training groups. Group 1 performed 1 resistance exercise training (RET) and 1 aerobic exercise training (AET) session per week (AET/RET 1 × wk−1); group 2 performed 2 RET and 2 AET sessions per week (AET/RET 2 × wk−1); and group 3 performed 3 RET and 3 AET sessions per week (AET/RET 3 × wk−1). MS, CF, and FT measurements were made pretraining and 16 weeks posttraining. Repeated-measures analysis of variance indicated a significant time effect for changes in MS, CF, and FT, such that all improved after training. However, there were no significant training group or training group 3 time interactions. Sixteen weeks of combined AET/RET (1 × wk−1, 2 × wk−1, or 3 × wk−1) lead to significant improvements in MS, CF, exercise economy, and FT. However, there were no significant differences for MS, CF, or FT outcomes between groups.

Keywords: strength, endurance, elderly, physical activity

Introduction

Disability rates among adults aged 65 years or older showed a steady decline during the 1990s; however, since the beginning of the 21st century, activities of daily living (ADL) disabilities have begun to gradually increase (11). According to the U.S. Center for Health Statistics, an average person spends about 15% of their lifespan in an unhealthy state because of disability, injury, or disease occurring in old age. Routine exercise is perhaps the most effective strategy to increase functional independence and reduce the prevalence of age-associated diseases (5). It is well established that aerobic exercise training (AET) improves cardiovascular fitness (CF), and resistance exercise training (RET) leads to improvement in muscle mass and strength in older adults (5,9,10). In addition to cardiovascular and skeletal muscle physiological improvements, regular exercise has also been shown to reduce the incidence of dementia, falls, osteoporosis, obesity, and delay the onset of age-associated cognitive decline (1,29,31,38). Current exercise recommendations for older adults suggest including both cardiovascular (a minimum of 3 × wk−1) and resistance (a minimum of 2 × wk−1) exercise training to counteract the detrimental effects of inactivity on health and ADL (5). However, to date, no specific guidelines for combined AET and RET in older adults have been established.

A meta-analysis performed by Baker et al. (1) revealed that current multimodal exercise programs had little effect on physical, functional, and quality of life outcomes in older adults, therefore it is important to develop training programs that will optimize fitness, strength, and functional gains in older adults. Although it was previously suggested that combining strength training with endurance training can compromise strength development (8,16,18), recent investigations in older adults have shown that combined resistance and endurance training can lead to similar or greater gains in muscular strength (MS) and CF as compared with RET or AET alone (17,23,39). Izquierdo et al. (24) showed that combined resistance (1 × wk−1) and endurance (1 × wk−1) training lead to similar gains in muscle mass, maximal strength, power, and , as compared with RET or AET alone . A follow-up study from this same group compared combined resistance (2 × wk−1) and endurance (2 × wk−1) with RET (2 × wk−1) or AET (2 × wk−1). They found that AET alone and combined resistance and endurance training resulted in similar increases in , whereas RET alone and combined resistance and endurance training showed similar increases in strength. However, only combined resistance and endurance training improved load carrying walk performance (17). These findings suggest that a training program consisting of a combination of AET and RET may be an effective way to improve overall health, fitness, and ADL in older adults.

Combined AET and RET training may be an effective means of training; however, the potential for inadequate recovery and excessive stress on the body cannot be disregarded. Performing either RET or AET alone at high intensities or volume can impair strength or aerobic fitness gains in older adults (22) and has been shown to reduce free living nontraining physical activity (NEAT) (12). The decrease in NEAT may occur because of training-induced fatigue (12). As previously described by Baker et al. (1), it is reasonable to conclude that one of the reasons initiation of exercise training is associated with high recidivism is that the new exercisers are overstressed and find it difficult to commit to the volume and frequency of training that are currently recommended for older adults. With this in mind, the potential for overstress in older adults may be increased dramatically in combined training programs where time and energy must be spent in training 2 divergent energy systems. Training too frequently may not allow enough time for recovery and may induce chronic fatigue and inhibit optimal training adaptations. However, not training frequently enough may reduce potential for improved fitness. Although a training frequency of at least 2 times per week has generally been considered to be the minimum training stimulation necessary to obtain either aerobic or strength adaptations (5), a recent investigation combining 1 day per week of AET and 1 day per week of RET suggest that this may be just as good for improving strength and aerobic fitness as more frequent training (23). Given the detrained state of many older adults, it is possible that substantial and similar improvements in strength and endurance may be observed with lower volumes of training. Furthermore, if a single session per week is shown to be as effective as multiple sessions per week for eliciting improvements in muscle strength and CF, it is likely that individuals would enhance exercise participation and adherence to training. Therefore, the aim of this study was, while keeping individual training session volumes constant, to compare the effects of different combined training frequencies (and thus total volume) of aerobic and resistance training for improving MS, CF, and ease of ADL in postmenopausal women older than 60 years. We hypothesize that group 2 (2 times per week aerobic and 2 times per week resistance training) will improve more on MS, CF, and ease of ADL after 16 weeks of exercise training than the other 2 groups.

Methods

Experimental Approach to the Problem

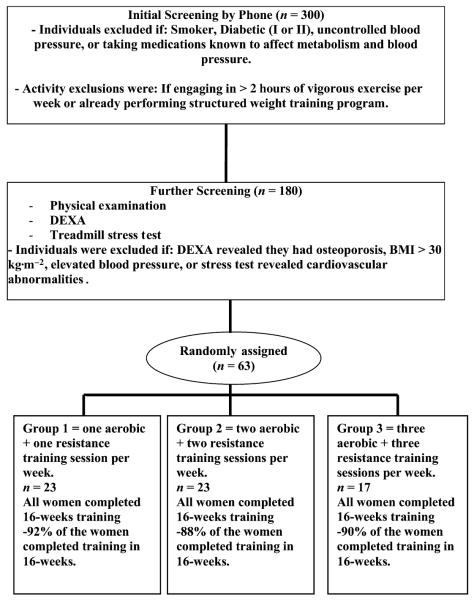

Subjects were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 exercise training groups. Group 1 performed 1 RET and 1 AET session per week; group 2 performed 2 RET and 2 AET sessions per week; and group 3 performed 3 RET and 3 AET sessions per week. Group 1 trained 2 times each week (one aerobic and the other resistance) on nonconsecutive days, group 2 trained 3–4 days each week (2 aerobic and 2 resistance), and group 3 trained between 4 and 6 days each week (3 aerobic and 3 resistance). Because of equivalent recruitment criteria for the proposed study, the 3 groups were comparable in every regard, except for the frequency of training. To improve adherence, subjects in groups 2 and 3 were allowed to have combined aerobic and resistance training sessions on the same day. Subjects in group 2 were allowed 1 combined training session each week, and subjects in group 3 were allowed 2 combined training sessions each week. Both groups 2 and 3 were required to have at least 1 training session each week in which only aerobic and only resistance training are performed. Each group performed their prescribed training of a combination of resistance and aerobic training for 16 weeks. Muscular strength, CF, functional task (FT), and body composition measurements were made pretraining and 16 weeks posttraining. Adherence to 16 weeks of training was 100% for each group. Ninety-two percent of the women in group 1, 88% of the women in group 2, and 90% of the women in group 3 completed 16 weeks of training without missing a session. If a session was missed because of sickness, injury, or personal reasons, the session was made up until 16 weeks of training was achieved, at least 3 consecutive weeks of training was achieved before posttraining measurements. We have illustrated this in the flow diagram in Figure 1. All testing was done in the morning, between 0700 and 0900 hours, after an overnight fast. Verbal encouragement was used for all tests.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants throughout the study.

Subjects

Subjects were 63 postmenopausal women between 60 and 77 years (Table 1) with a body mass index (BMI) <30 kg·m−2 and were physically untrained (self-reporting no exercise training to Program Coordinator at initial screening. Women engaging in structured exercise or already performing weight training exercise or routine walking were excluded from the study. Preliminary screening for study inclusion included a physical examination, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Participants were excluded from the study if they were hypertensive, displayed any abnormal ECG responses at rest or during exercise, or DEXA assessment revealed osteoporosis. Subjects had no history of heart disease or diabetes mellitus. Subjects were nonsmokers and were not taking medications known to affect energy expenditure, insulin level, heart rate (HR), or thyroid function. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all women provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and body composition changes pretraining and 16 weeks posttraining by exercise group.*†

| Group 1 (n = 23) |

Group 2 (n = 23) |

Group 3 (n = 17) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age = 66 ± 4 years |

Age = 65 ± 3 years |

Age = 65 ± 4 years |

G | T | G*T | ||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | P | P | P | |

| Height (cm) | 166.4 ± 6.7a | 166.8 ± 6.5a | 165.6 ± 5.7a | 165.6 ± 5.6a | 164.8 ± 4.1a | 164.8 ± 4.1a | 0.497 | 0.202 | 0.309 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.1 ± 11.4a,b,c | 78.3 ± 11,6a,b,c | 73.2 ± 10.1a,b | 72.7 ± 10.5a,b | 69.3 ± 9.4b,c | 68.8 ± 9.6b,c | 0.022 | 0.225 | 0.394 |

| BMI | 27.8 ± 4.1a | 27.6 ± 4.4b | 27.6 ± 3.3a | 27.4 ± 3.5b | 25.3 ± 3.5a | 25 ± 3.7b | 0.106 | 0.048 | 0.995 |

| % Fat | 44.2 ± 5.7a | 43.4 ± 6.4a | 43.3 ± 4.8a | 41.5 ± 4.5a | 40.7 ± 5.5a | 39.2 ± 6.6a | 0.09 | 0.001 | 0.339 |

| Lean mass (kg) | 42.6 ± 4a | 43.5 ± 4.4b | 41.7 ± 4.6a | 42.8 ± 5.3b | 40.7 ± 4.1a | 41.5 ± 3.7b | 0.454 | 0.042 | 0.317 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 34.4 ± 8.6a | 33.9 ± 9.1a | 31.9 ± 6.9a | 31.9 ± 10.9a | 28.6 ± 6.8a | 27.4 ± 7.5a | 0.059 | 0.461 | 0.792 |

G = intervention group; T = time; G*T = group × time interaction; BMI = body mass index.

All data are presented as means ± SDs. Statistically different within group means are represented by different superscripts.

Strength Testing

Before pretraining strength measurement, 2 exercise sessions within the first week were used to familiarize the subjects with the movement patterns of the exercise. The maximum amount of weight that could be lifted once (1 repetition maximum [RM]) was measured for leg press, knee extension, hamstring curl, bicep curl, chest press, and shoulder press. Measurement of 1 RM was done using previously reported methods (26). Briefly, after a warm-up, subjects lifted progressively heavier weights until 2 consecutive failures occurred. Coefficient of variability for 1 RM testing in our lab is less than 3%. The 1 RM results of leg press, knee extension, and hamstring curl were averaged to provide an overall index of lower-body strength, whereas the bicep curl, chest press, and should press were averaged to provide an overall index of upper-body strength.

Aerobic Capacity Testing

Maximum oxygen uptake () was measured by indirect calorimetry on a treadmill using a modified Bruce Protocol. Subjects warmed up for 4 minutes at a speed of 3 mph on a 2.5% grade; grade was increased 2.5% each minute until volitional exhaustion. Volume of O2 and CO2 was measured continuously by open-circuit spirometry and analyzed using a Sensormedics metabolic measurement cart (model 2900; Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). Heart rate was monitored by a Polar Vantage XL HR monitor (Polar Beat, Port Washington, NY, USA). The highest achieved within the last 2 minutes of exercise was recorded as . Coefficient of variability for in our laboratory is less than 2%.

Functional Tasks

Five FTs were selected to mimic commonly performed activities of older adults in a free-living condition. The FTs were level walking at 0% grade at 3 mph (4.8 km·h−1) for 4 minutes, tandem walk, 25-ft walk test, chair standing test, and a stair climb test. The tasks were performed in the same order for each test condition to avoid potential bias. The best trial for each FT was used in the statistical analyses.

Level Walk Test

Subjects walked on a treadmill at 0% grade at 3 mph for 4 minutes. The submaximal and HR were obtained in the steady state during the third and fourth minute (3).

Tandem Walk

Subjects were instructed to walk forward and backward over a 20-ft course and were timed concurrently (35). Proper technique included walking heel to toe as fast and as safely as possible. One practice trial and 2 test trials for each direction were performed. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.953.

Twenty-five-Foot Walk Test

Each subject was timed with a stopwatch as they walked over a straight 25-ft expanse of floor. To allow for acceleration and deceleration, the course included 15 extra feet, both ahead of and at the end of the 25-ft distance that was marked and measured. Subjects were instructed to walk as fast and as safe as possible through the course (2,20,35). Two test trials were administered. The ICC for this test was 0.910.

Stair Climbing Tests

Subjects performed a modified stair climb test (34). Briefly, subjects were instructed to walk up one flight of 12 steps (7 inches high × 11.5 inches deep) as fast and as safe as possible. Each subject was allowed to maintain contact with the handrail throughout the test if desired or could grab the handrail at any time during the test. The use of the handrail was for safety, but subjects were not allowed to pull themselves forward during the test using the handrail. Two trials were performed and timed. The ICC for this test was 0.781.

Sit-to-Stand Test

Subjects were instructed to sit in the middle of a chair (positioned against a wall) with back straight, feet flat on the floor, and arms crossed at the wrists and held against the chest. On the signal “go,” subjects rose to a full stand, then returned to a fully seated position and repeated this procedure as fast as possible for 30 seconds (20). Before testing, each subject was allowed to practice 1 or 2 stands to ensure proper form.

Resistance and Aerobic Training Program

All exercise sessions were conducted by a master’s degree level exercise physiologist in the Bell Training Facility or in the exercise facility in the Nursing building on the University of Alabama at Birmingham campus. Each supervised training session included 3–5 individuals. The duration of the resistance exercise sessions was approximately 60–90 minutes; this included a brief warm-up and 45- to 60-minute lower- and upper-body resistance training sessions. Each exercise session began with a 3-minute warm-up on either a treadmill or cycle ergometer at low intensity. Subjects performed the following resistance training exercises: squats, leg press, leg extension, hamstring curl, bench press, military press, elbow flexion, and triceps extension. Subjects began the resistance training program with 1 set of 10 repetitions at an intensity of 60% of their 1 RM and progressed to 2 sets of 10 repetitions at 80% of 1 RM by week 6. During week 7, subjects began performing explosive concentric squats both unloaded and loaded at the end of each workout, gradually increasing to 2 sets of both unloaded and loaded explosive concentric squats at 50% of 1 RM for 8 repetitions. Briefly, the loaded explosive concentric squats were performed on a plate-loaded squat machine. The unloaded explosive concentric squats were performed on a flat surface in the Bell Training Facility, with the participants squatting down to 90° (or as close as to 90° as possible) with hands on hips. Once at this position, the explosive vertical jump would ensue.

Subjects performed aerobic exercise on a treadmill or cycle ergometer (95% of aerobic exercise was performed on a treadmill). Subjects trained initially for 20 minutes at 65% of maximum heart rate (MHR) and progressively increased their training until they were able to exercise continuously for 40 minutes at 80% of MHR. Heart rate was monitored throughout each session by a Polar Vantage XL HR monitor (Polar Beat).

Body Composition Measurements

Body composition was measured by DEXA (Prodigy; Lunar Radiation, Madison, WI, USA). The scans were analyzed with the use of ADULT software, version 1.33 (Lunar Radiation).

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed with SPSS (version 18; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The means and SDs for all quantitative data were calculated for each group. Overall comparisons of the change in MS, aerobic capacity, and FTs by group were performed using repeated-measures analysis of variance. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine associations between changes in strength, , and FTassessments. For all analyses, a p value <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Anthropometric and Body Composition

Anthropometric and body composition data of the participants pretraining and 16-weeks posttraining are shown in Table 1. Age, height, %fat, fat mass, lean mass, and BMI were not significantly different between training groups. There was a significant group difference in body mass, such that group 3 had a significantly lower-body mass as compared with group 1 (p = 0.022). A significant time effect was observed for lean mass, %fat, and BMI, such that lean mass increased (p < 0.042), whereas %fat and BMI decreased (p < 0.001 and p = 0.048, respectively) after training in all 3 groups.

Strength Assessments

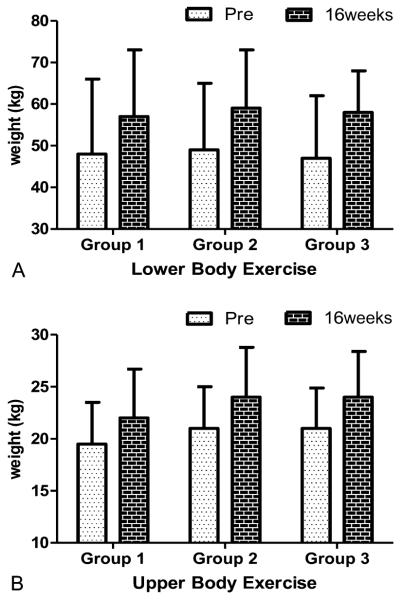

The effects of training group, time, and training group × time interactions for each strength measurement are shown in Table 2. A significant time effect was observed for all strength measurements (p < 0.001). There was no significant effect for training group or training group × time on any of the strength measurements measured. The cumulative results of upper- and lower-body changes in strength are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Aerobic capacity, functional tasks, and strength changes pretraining and 16 weeks posttraining by exercise group.*†

| Group 1 (n = 23) |

Group 2 (n = 23) |

Group 3 (n = 17) |

G | T | G*T | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | P | P | P | |

| (ml·kg−1·min−1) | 21.6 ± 5a | 22 ± 5b | 22.8 ± 4a | 24.4 ± 5b | 23.2 ± 8a | 23.7 ± 7b | 0.372 | 0.035 | 0.344 |

| Tandem walk (s) | 19.5 ± 6a | 15.9 ± 5b | 16.4 ± 5a | 14.9 ± 4b | 18.4 ± 5a | 16.9 ± 4b | 0.224 | 0.001 | 0.123 |

| 25-ft walk test (s) | 3.4 ± 0.5a | 3.3 ± 0.5b | 3.3 ± 0.6a | 3.1 ± 0.6b | 3.4 ± 0.5a | 3.3 ± 0.4b | 0.700 | 0.001 | 0.554 |

| Stair climb (s) | 3.9 ± 0.7a | 3.8 ± 0.5b | 3.7 ± 0.6a | 3.6 ± 0.7b | 3.8 ± 0.5a | 3.7 ± 0.5b | 0.176 | 0.017 | 0.439 |

| Sit-to-stand test (reps) | 13.9 ± 4a | 15.9 ± 4b | 15.6 ± 3a | 17.8 ± 4b | 15 ± 3a | 17 ± 4b | 0.151 | 0.001 | 0.778 |

| Leg press (kg) | 93 ± 26a | 112 ± 32b | 97 ± 20a | 115 ± 29b | 88 ± 18a | 111 ± 22b | 0.652 | 0.001 | 0.545 |

| Knee extension (kg) | 31 ± 9a | 37 ± 10b | 31 ± 8a | 39 ± 9b | 33 ± 6a | 39 ± 6b | 0.658 | 0.001 | 0.620 |

| Hamstring curl (kg) | 19 ± 4a | 22 ± 4b | 20 ± 3a | 23 ± 3b | 20 ± 4a | 24 ± 3b | 0.131 | 0.001 | 0.986 |

| Bicep curl (kg) | 14 ± 2a | 16 ± 2a | 15 ± 4a | 17 ± 3a | 15 ± 2a | 17 ± 2a | 0.221 | 0.001 | 0.099 |

| Chest press (kg) | 22 ± 5a | 25 ± 7b | 23 ± 5a | 28 ± 6b | 24 ± 5a | 29 ± 7b | 0.306 | 0.001 | 0.234 |

| Shoulder press (kg) | 22 ± 5a | 25 ± 5b | 25 ± 4a | 27 ± 6b | 24 ± 5a | 26 ± 8b | 0.099 | 0.001 | 0.507 |

G = intervention group; T = time; G*T = group × time interaction.

All data are presented as means ± SDs. Statistically different within group means are represented by different superscripts.

Figure 2.

A and B) Changes in upper- and lower-body strength after 16 weeks of training. A significant time effect was observed for all strength measurements (p < 0.001).

Aerobic Capacity

Training group, time, and training group × time interactions for are shown in Table 2. There was a significant ime effect for (p = 0.035); however, no significant training group or training group × time interactions were found. Each training group had an increase in after 16 weeks of training.

Functional Tests

The effects of training group, time, and training group × time interactions for each functional test are shown in Table 2. Similar to the strength assessments, a significant time effect was observed for each of the functional tests performed (p < 0.001 for all except the stair climb; p = 0.017). Each of the groups performed significantly better as compared with pretraining assessments. There was no significant effect of training group or training group × time on any of the functional tests.

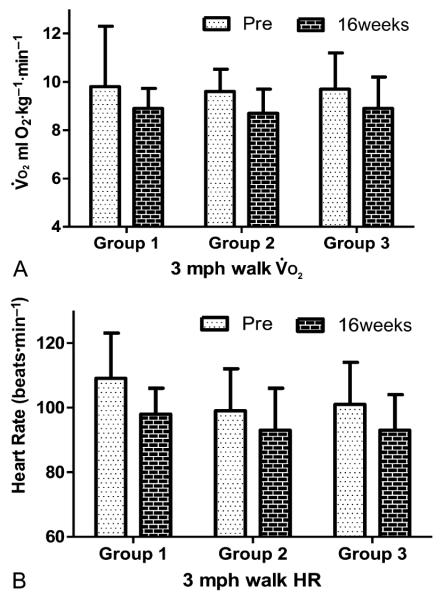

The and HR responses to the 3 mph flat walk test are shown in Figure 3. There was a significant time effect for and HR responses to walking on the flat (p < 0.001). Each group was able to perform the walk test while requiring a lower and HR after 16 weeks of training. No significant effect of training group or training group 3 time interactions was found for either variable.

Figure 3.

Changes in heart rate and to 3 mph flat walk test after 16 weeks of training. A significant time effect was observed for and heart rate (p < 0.001).

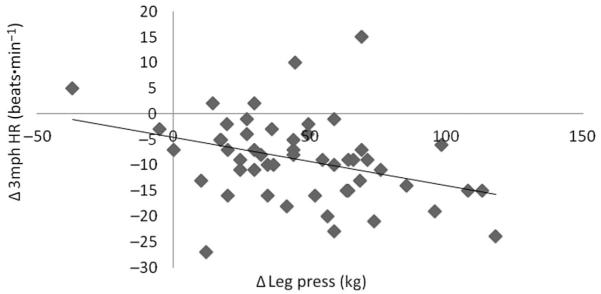

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant correlations between change in leg press strength and 3 mph walk HR (r = 0.295, p = 0.030), such that a greater improvement in leg press strength results in a lower HR response to the 3mph walking test (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in 3 mph heart rate significantly associated with change in leg press following 16-weeks of training (r = 0.295, p = 0.030).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing different frequencies of combined AET/RET on MS, CF, and lower extremity function/mobility in elderly women. The main findings of this study were that 16 weeks of combined AET/RET (1 × wk−1, 2 × wk−1, or 3 × wk−1) lead to significant improvements in MS, CF, exercise economy, and lower extremity FTs. However, there were no significant differences for any of the cardiovascular, MS, or lower extremity FT outcomes between training groups. The present observations suggest that performing combined AET/RET as little as 1 × wk−1 can significantly improve strength and endurance in older women. Perhaps more important, the ability to perform common tasks of daily living (such as sitting, standing, climbing stairs, and walking) also significantly improved with combined AET/RET as little as 1 × wk−1.

A unique finding of this study was that frequency (1 × wk−1, 2 × wk−1, or 3 × wk−1) of combined AET/RET did not differ in improving strength, endurance, or lower extremity FT outcomes in women aged 60 years and older. Several earlier investigations have shown that concurrent endurance training with strength training may blunt the strength-induced changes in strength or muscle mass as compared with strength training alone (15,27,32). However, the majority of studies supporting this hypothesis was performed in men and used high-volume and high-intensity training protocols. We had previously shown that interference in strength occurred in untrained young men and women training 4 times per week but did not occur in men and women who were untrained for resistance training but were aerobically trained for the previous 6 months (18). One interpretation of this study is that the men and women who were untrained for aerobic and resistance training were overstressed, whereas the men and women who were previously aerobically trained and continued to train while adding resistance training to their regimen were able to tolerate the stress of the combined training. More recent studies performed on older adults have shown that combined AET/RET (1 × wk−1 or 2 × wk−1) can induce similar gains in muscle mass, strength, physical fitness, and lean body mass than either strength or endurance training alone (24,33). These findings further support the notion that combined AET/RET can be used as an effective mode of training even when the frequency is × times per week without interfering with fitness or MS development in previously untrained older adults. One caveat that should be made to this interpretation of this study is that the duration of training was only 16 weeks. It is impossible to predict with any degree of certainty what the outcome would be for longer periods of combined training.

There is a paucity of information regarding the frequency of combined AET/RET on CF and strength development in older adults. These data suggest that 1 × wk−1 of combined AET/RET for 16 weeks was just as effective in improving strength, endurance, and lower extremity FTs as 2 and 3 × wk−1. The most profound improvements were found in measures of MS and lower extremity FTs. We observed a 21% increase in lower-body strength (group 1 = 19%, group 2 = 20%, and group 3 = 23%) and a 14% increase in upper-body strength (group 1 = 13%, group 2 = 15%, and group 3 = 15%) from pretraining to 16 weeks posttraining. This study used 2 familiarization strength training sessions before any strength testing to ensure that the subjects had developed the confidence and motor patterns to perform each strength test. We would therefore expect the lower increases in strength than other studies that did not use a familiarization period. In addition, it is difficult to compare our overall upper- and lower-body strength measures with previous investigations because different strength measurements were assessed; however, the 21% increase in knee extension 1 RM found in the present study was similar to changes previously reported in older women (24–29% increase) engaging in 6 months of heavy resistance training (13). However, other studies have shown larger increases in strength in older adults (21,37), and at least one study showed an inverse relationship between training intensity and strength increases in older women (19). However, we cannot rule out that the combined training for the 4 days per week and 6 days per week training did not prohibit larger increases in strength.

Several studies have shown that a significant increase in (10–30%) can occur in older adults if the training stimulus is of adequate intensity (50–85% ), duration (>20 minutes per session), and frequency (3–5 sessions per week) (6,33,36). Magnitude of increase in in this study (3% increase) was much smaller as compared with previous investigations in older women (26% increase) engaging in endurance training alone (6); however, the duration of training for this study was 4 months as opposed to 9–12 months. These differing responses may have been due to the shorter training period used in our study. A previous study using combined AET/RET (2 × wk−1) showed a 16% increase in after 21 weeks of training (33); however, it is difficult to compare results between studies because their participants consisted of women aged 39–65 years as compared with women older than 60 years in the present study. A longer training period of combined AET/RET may be needed to see greater magnitudes of change in in women aged 60 years and older.

In the present study, an 8% decrease in HR and a 9% decrease in for submaximal (3 mph walk test) exercise were observed after 16 weeks of combined AET/RET. This improvement in exercise economy during submaximal activities is perhaps even more important than overall changes in peak CF in this population. With aging, the ability to perform daily FTs becomes increasingly difficult. Sarcopenia impairs the ability to perform FTs and increases the risks of frailty, falls, and fractures. Furthermore, sarcopenia makes it difficult to engage in physical activity, which increases the manifestation of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (25). It is likely that a combination of improving strength and exercise economy will enable older adults to move with less difficulty, thus making physical activity less demanding and increasing the likelihood of becoming physically active.

In addition to assessing changes in strength and endurance, the assessment of lower extremity FTs enabled us to relate these changes to walking and stair climbing. After the 16 weeks of training, the time required to perform the tandem walk, 25-ft walk, and stair climb tests decreased by 13, 4, and 2.7%, respectively, whereas the 30-second sitto-stand test improved by 14%. We have previously shown that the knee extensors were the primary leg muscles activated during the sit-to-stand test, and the activation of the knee extensors was significantly greater in older women as opposed to younger women (28). Although there was a 21% increase in knee extension strength and a 14% improvement in the sit-to-stand test, these variables were not independently associated. Therefore, it is likely that a combination of improvements in strength and endurance that led to improvements in the sit-to-stand test. The age-related decline in the ability to perform FTs is important to consider, given the fact that the average life expectancy has gradually increased. Engaging in exercise training that leads to improvement in both endurance and strength is perhaps the best strategy to combat this age-associated decline in FT performance. Consistent with results from this study, previous work from our group (14) and others (4,7) have shown that small increases in MS can significantly improve performance of upper- and lower-body FTs and overall mobility. However, it is well known that aerobic training increases and stroke volume, which also contribute to reduced HR at rest and during submaximal exercise (30). Therefore, it is probable that increases in both aerobic capacity and strength contributed to the decreases in submaximal HR. Collectively, the present study demonstrates that in previously untrained women aged 60 years and older, a combined AET/RET program performed as little as 1 × wk−1 or as much as 3 × wk−1 can improve CF, MS, and lower extremity function/mobility.

Practical Applications

In summary, the present results suggest that 16 weeks of combined AET/RET (1 × wk−1, 2 × wk−1, or 3 × wk−1) is an effective way to improve MS, CF, exercise economy, and lower-body FTs in healthy postmenopausal women older than 60 years. Furthermore, the improvements observed after 16 weeks of training were not significantly different when performed 1 × wk−1 as compared with either 2 or 3 × wk−1. A low-frequency combined AET/RET program may be an ideal method of training to optimize strength, endurance, and improving quality of life in older adults. Thus, health practitioners should consider incorporating this form of exercise training when an individual is unable to perform vigorous exercise or higher training frequencies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01AG027084-01, P30-DK56336, and T32DK062710-07. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Baker MK, Atlantis E, Fiatarone Singh MA. Multi-modal exercise programs for older adults. Age Ageing. 2007;36:375–381. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohannon RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26:15–19. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brock DW, Chandler-Laney PC, Alvarez JA, Gower BA, Gaesser GA, Hunter GR. Perception of exercise difficulty predicts weight regain in formerly overweight women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:982–986. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler JM, Hadley EC. Exercise to improve physiologic and functional performance in old age. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:761–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chodzko-Zajko W, Proctor D, Fiatarone Singh M, Minson C, Nigg C, Salem G, Skinner J, Medicine ACoS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coggan AR, Spina RJ, King DS, Rogers MA, Brown M, Nemeth PM, Holloszy JO. Skeletal muscle adaptations to endurance training in 60- to 70-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:1780–1786. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis JW, Ross PD, Preston SD, Nevitt MC, Wasnich RD. Strength, physical activity, and body mass index: Relationship to performance-based measures and activities of daily living among older Japanese women in Hawaii. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:274–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley G, Djamil R. Incompatibility of endurance- and strength-training modes of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:1446–1451. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferri A, Scaglioni G, Pousson M, Capodaglio P, Van, Hoecke J, Narici M. Strength and power changes of the human plantar flexors and knee extensors in response to resistance training in old age. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:69–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frontera W, Meredith C, O’Reilly K, Evans W. Strength training and determinants of VO2max in older men. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:329–333. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.1.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller-Thomson E, Yu B, Nuru-Jeter A, Guralnik J, Minkler M. Basic ADL disability and functional limitation rates among older AMERICANS from 2000-2005: The end of the decline? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1333–1336. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goran M, Poehlman E. Endurance training does not enhance total energy expenditure in healthy elderly persons. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:E950–957. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häkkinen K, Pakarinen A, Kraemer WJ, Newton RU, Alen M. Basal concentrations and acute responses of serum hormones and strength development during heavy resistance training in middle-aged and elderly men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:B95–B105. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.b95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman MJ, Fields DA, Byrne NM, Hunter GR. Resistance training improves metabolic economy during functional tasks in older adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21:91–95. doi: 10.1519/00124278-200702000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickson RC. Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1980;45:255–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00421333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickson R, Rosenkoetter M, Brown M. Strength training effects on aerobic power and short-term endurance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12:336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holviala J, Häkkinen A, Karavirta L, Nyman K, Izquierdo M, Gorostiaga E, Avela J, Korhonen J, Knuutila V, Kraemer W, Häkkinen K. Effects of combined strength and endurance training on treadmill load carrying walking performance in aging men. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:1584–1595. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181dba178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter G, Demment R, Miller D. Development of strength and maximum oxygen uptake during simultaneous training for strength and endurance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1987;27:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter GR, Treuth M. Relative training intensity and increases in strength in older females. J Strength Cond Res. 1995;9:188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter GR, Treuth MS, Weinsier RL, Kekes-Szabo T, Kell SH, Roth DL, Nicholson C. The effects of strength conditioning on older women’s ability to perform daily tasks. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:756–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter GR, Wetzstein CJ, Fields DA, Brown A, Bamman MM. Resistance training increases total energy expenditure and free-living physical activity in older adults. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:977–984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter GR, Wetzstein C, McLafferty CJ, Zuckerman P, Landers K, Bamman M. High-resistance versus variable-resistance training in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1759–1764. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izquierdo M, Häkkinen K, Ibáñez J, Kraemer W, Gorostiaga E. Effects of combined resistance and cardiovascular training on strength, power, muscle cross-sectional area, and endurance markers in middle-aged men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;94:70–75. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izquierdo M, Ibañez J, Häkkinen K, Kraemer WJ, Larrión JL, Gorostiaga EM. Once weekly combined resistance and cardiovascular training in healthy older men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:435–443. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000117897.55226.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen I, Ross R. Linking age-related changes in skeletal muscle mass and composition with metabolism and disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:408–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalb JS, Hunter GR. Weight training economy as a function of intensity of the squat and overhead press exercise. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991;31:154–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraemer WJ, Patton JF, Gordon SE, Harman EA, Deschenes MR, Reynolds K, Newton RU, Triplett NT, Dziados JE. Compatibility of high-intensity strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adaptations. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:976–989. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landers KA, Hunter GR, Wetzstein CJ, Bamman MM, Weinsier RL. The interrelationship among muscle mass, strength, and the ability to perform physical tasks of daily living in younger and older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:B443–448. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.b443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Littman AJ, Kristal AR, White E. Effects of physical activity intensity, frequency, and activity type on 10-y weight change in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:524–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McArdle W, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise Physiology. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E, Guralnik J. Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:695–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sillanpää E, Häkkinen A, Nyman K, Mattila M, Cheng S, Karavirta L, Laaksonen DE, Huuhka N, Kraemer WJ, Häkkinen K. Body composition and fitness during strength and/or endurance training in older men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:950–958. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318165c854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sillanpää E, Laaksonen DE, Häkkinen A, Karavirta L, Jensen B, Kraemer WJ, Nyman K, Häkkinen K. Body composition, fitness, and metabolic health during strength and endurance training and their combination in middle-aged and older women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:285–296. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skelton DA, Young A, Greig CA, Malbut KE. Effects of resistance training on strength, power, and selected functional abilities of women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1081–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taaffe DR, Duret C, Wheeler S, Marcus R. Once-weekly resistance exercise improves muscle strength and neuromuscular performance in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1208–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas SG, Cunningham DA, Thompson J, Rechnitzer PA. Exercise training and “ventilation threshold” in elderly. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:1472–1476. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treuth MS, Hunter GR, Weinsier RL, Kell SH. Energy expenditure and substrate utilization in older women after strength training: 24-h calorimeter results. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:2140–2146. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.6.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villareal DT, Binder EF, Yarasheski KE, Williams DB, Brown M, Sinacore DR, Kohrt WM. Effects of exercise training added to ongoing hormone replacement therapy on bone mineral density in frail elderly women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:985–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood R, Reyes R, Welsch M, Favaloro-Sabatier J, Sabatier M, Matthew Lee C, Johnson L, Hooper P. Concurrent cardiovascular and resistance training in healthy older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1751–1758. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]