Infiltration of inflammatory cells into adipose tissue causes insulin resistance in animal models and is associated with insulin resistance in humans (1,2). Among potential therapeutic approaches, the hormone erythropoietin (EPO) exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a variety of nonerythroid tissues (3), in which the receptor for EPO (EPO-R) is widely expressed (4). Various observations suggest a relationship between EPO and diabetes. There is an increased prevalence of anemia with inadequate EPO response in diabetes (5), and treatment of anemia slows the progression of microvascular and macrovascular complications (6). EPO reduced glucose levels in nondiabetic humans (7) and reduced diet-induced obesity and suppressed gluconeogenesis in rodents (8,9). While EPO increases adipose tissue oxidative metabolism and deletion of EPO in adipocytes results in obesity (10), failure to reproduce this highlights potential genetic and environmental influences (11). EPO has cytoprotective, proliferative, and anti-inflammatory effects in a variety of tissues including pancreatic β-cells, protecting against experimental models of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (12,13).

In this issue, Alnaeeli et al. (14) elegantly demonstrate a pharmacologic role of EPO in attenuating adipose tissue inflammation prior to changes in body weight. The authors show that EPO-R is disproportionately highly expressed in adipocytes and adipose inflammatory cells, and both pharmacologic and endogenous EPO promote the skewing of adipose macrophages to an alternatively activated, predominantly M2 state. Beneficial roles of EPO are not only abolished when EPO is given to mice lacking EPO-R except in erythroid cells, but these EPO-R−deficient mice have an unopposed proinflammatory phenotype with predominance of M1-activated macrophages. Thus, the predominance of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in the lean nondiabetic state may be at least in part restrained by endogenous EPO. As M2 macrophages play an important role in tissue growth and differentiation, beneficial effects of EPO in tissue injury may be achieved through effects on macrophages in addition to a direct cytoprotective role.

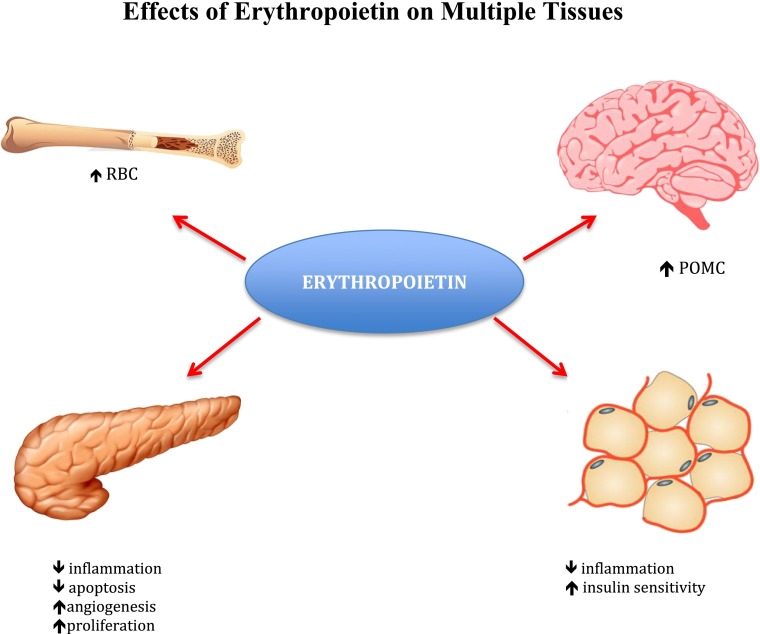

While Alnaeeli et al. attributed EPO’s metabolic benefit to effects on adipose tissue macrophages, their finding that EPO expression is high in stromal vascular fraction cells suggests that EPO might exert its effects via other inflammatory cells, which in turn could impact the inflammatory status of adipose macrophages (15). As EPO’s effects on glucose tolerance and inflammation were more striking than on insulin sensitivity, these effects may represent an association rather than a causal relationship. Indeed, some of the observed metabolic effects may be attributable to EPO’s effects on β-cells (12). Could there be an additional role for the brain in mediating EPO’s effects? EPO-R is abundantly expressed in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons (16), and glucose sensing by POMC neurons contributes to regulation of systemic glucose metabolism (17). Another intriguing question is whether some of the insulin-sensitizing effects might be mediated by EPO-induced decreases in systemic iron stores (18), given the known association between iron overload and insulin resistance (19) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Erythroid and nonerythroid effects of EPO. Under hypoxic conditions, EPO promotes increased production of red blood cells (RBC). In the hypothalamus, EPO-Rs expressed in POMC-producing neurons regulate food intake and energy expenditure. In white adipose tissue, EPO decreases inflammation, normalizing insulin sensitivity and reducing glucose intolerance. In the pancreas, EPO exerts anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, proliferative, and angiogenic effects on β-cells.

The study by Alnaeeli et al. (14) provides novel insights into both pharmacologic and endogenous roles of EPO that improve glucose tolerance and reduce inflammation. Thus, EPO’s extra-erythropoietic actions may offer novel approaches to diabetes prevention and treatment. As increased risk of thrombogenesis and hypertension (4) suggest that EPO be used cautiously in diabetes, selectively harnessing EPO’s favorable metabolic effects may have therapeutic potential (20).

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors wish to acknowledge the intellectual contributions of Drs. Cynthia Luk and Elizabeth Sanchez.

Funding. This work was supported by funding to M.W. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP- 81148) and to M.H. from the National Institutes of Health (DK69861 and DK79974) and the American Diabetes Association. M.W. holds a Canada Research Chair in Signal Transduction in Diabetes Pathogenesis. M.H. is a Beeson Scholar of the American Federation for Aging Research.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

See accompanying article, p. 2415.

References

- 1.Ferrante AW., Jr The immune cells in adipose tissue. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15(Suppl. 3):34–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koppaka S, Kehlenbrink S, Carey M, et al. Reduced adipose tissue macrophage content is associated with improved insulin sensitivity in thiazolidinedione-treated diabetic humans. Diabetes 2013;62:1843–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cravedi P, Manrique J, Hanlon KE, et al. Immunosuppressive effects of erythropoietin on human alloreactive t cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27 March 2014 [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JW. Erythropoietin: physiology and pharmacology update. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Tsalamandris C, MacIsaac R, Jerums G. Anemia with impaired erythropoietin response in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:466–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill JB, Bell DS. Anemia and the role of erythropoietin in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2006;20:262–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. CREATE Investigators Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2071–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz O, Stuible M, Golishevski N, et al. Erythropoietin treatment leads to reduced blood glucose levels and body mass: insights from murine models. J Endocrinol 2010;205:87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng R, Zhu D, Bi Y, Yang D, Wang Y. Erythropoietin inhibits gluconeogenesis and inflammation in the liver and improves glucose intolerance in high-fat diet-fed mice. PLoS One 2013;8:e53557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Teng R, Di L, et al. PPARα and Sirt1 mediate erythropoietin action in increasing metabolic activity and browning of white adipocytes to protect against obesity and metabolic disorders. Diabetes 2013;62:4122–4131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luk CT, Shi SY, Choi D, Cai EP, Schroer SA, Woo M. In vivo knockdown of adipocyte erythropoietin receptor does not alter glucose or energy homeostasis. Endocrinology 2013;154:3652–3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi D, Schroer SA, Lu SY, et al. Erythropoietin protects against diabetes through direct effects on pancreatic beta cells. J Exp Med 2010;207:2831–2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi D, Retnakaran R, Woo M. The extra-hematopoietic role of erythropoietin in diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev 2011;7:284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alnaeeli M, Raaka BM, Gavrilova O, Teng R, Chanturiya T, Noguchi CT. Erythropoietin signaling: a novel regulator of white adipose tissue inflammation during diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 2014;63:2415–2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Har D, Carey M, Hawkins M. Coordinated regulation of adipose tissue macrophages by cellular and nutritional signals. J Investig Med 2013;61:937–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teng R, Gavrilova O, Suzuki N, et al. Disrupted erythropoietin signalling promotes obesity and alters hypothalamus proopiomelanocortin production. Nat Commun 2011;2:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey M, Kehlenbrink S, Hawkins M. Evidence for central regulation of glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem 2013;288:34981–34988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodnough LT, Skikne B, and Brugnara C. Erythropoietin, iron, and erythropoiesis. Blood 2000;96:823−833 [PubMed]

- 19.Fernández-Real JM, Ricart-Engel W, Arroyo E, et al. Serum ferritin as a component of the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes Care 1998;21:62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brines M, Patel NS, Villa P, et al. Nonerythropoietic, tissue-protective peptides derived from the tertiary structure of erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:10925–10930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]