SUMMARY

A joint model for a longitudinal biomarker and recurrent events is proposed. This general model accommodates the effects of covariates on the biomarker and event processes, the effects of accumulating event occurrences, and effects caused by interventions after each event occurrence. Association between the biomarker and recurrent event processes is captured through a latent class structure, which also serves to handle an underlying heterogeneous population. We use the EM algorithm for maximum likelihood estimation of the model parameters and a penalized likelihood measure to determine the number of latent classes. This joint model is validated by simulation and illustrated with a data set from epileptic seizure study.

Keywords: latent class model, recurrent events, joint model, longitudinal biomarker, heterogeneous population

1. INTRODUCTION

In many biomedical studies both a longitudinal biomarker and recurrent event times are collected on each subject. Instances include reoccurrence of prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a longitudinal biomarker, reoccurrence of heart attacks with the longitudinal biomarker being cholesterol level or blood pressure level, and repeated hospitalizations due to a chronic disease such as hepatitis with liver enzyme (transaminase) blood level as a biomarker.

A biomarker is a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention [1]. Biomarkers can strengthen the analysis of event occurrences by providing additional information relevant to event occurrence times for subjects having censored values [2].

As discussed in [3, Section 6.3.2], a biomarker is an internal covariate that can only be observed while the individual survives and consequently may provide information on the event-time outcome. A biomarker indicates the progress or status in some sense toward failure [4]. It is evident that biomarker variables should not be treated in the same fashion as time-dependent explanatory covariates in failure time data analysis, owing to the fact that the biomarkers are correlates of survival time or residual lifetime [3, Section 6.3.2]. A reviewer has also noted the similarity between this marker process and a degradation process that is commonly monitored in reliability and engineering studies (see for instance, [5, 6]).

In modeling the recurrent event process, apart from considerations of the biomarker, it is important to accommodate the effects of interventions that are performed after each event occurrence, the weakening or strengthening impact on the subject of accumulating event occurrences, the effect on the rate of event occurrence of possibly time-dependent covariates, and the potential correlation among event occurrences within each subject. Furthermore, by virtue of the data accrual scheme, the number of events observed over the study period is random and is informative about the stochastic mechanism governing the event occurrence. In addition, the censoring mechanism associated with the inter-event time encompassing the end of the study period or censoring time is also informative about the event occurrence process [7]. Peña and Hollander [8] and Peña et al. [9] proposed and studied a general class of models that addresses these important aspects inherent with recurrent events, but did not additionally incorporate a longitudinal biomarker.

In Lin et al. [10], a latent class approach for the joint modeling of a longitudinal biomarker and a survival outcome was proposed and studied. Latent class models simplify the association of biomarker and event outcomes through a conditional independence (CI) assumption by which the longitudinal biomarker and the occurrence of event are stochastically independent given a subject falling in one particular class. Latent class models accommodate a heterogeneous population and capture subpopulation structure [11] as well as protect against model misspecification in other approaches.

As a result of the appealing advantages of the latent class model framework in Lin et al. [10], and the generality of the recurrent event model of Peña and Hollander [8], we propose a combination of these two models to attain a latent class joint model that connects a longitudinal biomarker to recurrent event occurrences. This joint model generalizes the single event latent class model of Lin et al. [10] to the situation of recurrent events, and includes the latent pattern mixture models for informative intermittent missing data [12] as a special case, under a parametric setting. Such a model will find applications in the statistical modeling and analysis of survival data from biomedical studies, lifetime data from reliability and engineering studies, and data from economic and financial settings. An excellent overview of the rationale and development of joint models can be found in [13].

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the latent class joint model. Section 3 presents the parameter estimation methods and Section 4 reports our simulation study investigating the properties of these estimators. In Section 5, we use the joint model to analyze recurrent epileptic seizures. We conclude with a discussion in Section 6.

2. THE LATENT CLASS JOINT MODEL

The latent class joint model is a finite mixture model with covariates, where each observation can be viewed as arising from a population which is a mixture of a finite number of subpopulations or classes. Each class corresponds to a subpopulation that has its own pattern of longitudinal and recurrent event responses. The longitudinal biomarker and recurrent event are connected only through the unknown latent class, and they are assumed to be independent given the latent class to which the unit belongs.

In this latent class joint model, the probability that a subject belongs to a latent class is modeled by a multinomial logit model with subject-specific covariates. The longitudinal biomarker is modeled by a linear mixed model with a common fixed effect, a subject-specific random effect, a class-specific fixed effect, and a common background random noise. The recurrent event hazard is modeled by a class-specific intensity and related covariates.

2.1. The class membership submodel

Let n be the total number of subjects, K the total number of latent classes, and l the number of covariates. Assume that ci = (ci1, …, ciK) has a multinomial distribution with cik the indicator variable for subject i in class k. The latent class vector is modeled through a multinomial logit regression in which the probability P(cik = 1) that subject i falls into class k is given by

| (1) |

where vi = (vi1, …, vil)T is the covariate vector, ηk is the class-specific coefficient vector with η1 =0, and ci = (ci1, …, ciK)T ~ Multinomial(πi1, …, πiK), .

2.2. The longitudinal biomarker submodel

Let ni be the number of biomarker observations for subject i, p be the number of common fixed effect covariates, q1 be the number of subject-specific random covariates, and q2 be the number of class-specific fixed covariates. The longitudinal biomarker yi for subject i is postulated to follow a heterogeneous random effects model given by

| (2) |

where (yi)ni×1 = (yi1, …, yini)T is the vector of biomarker readings for subject i, (Xi)ni × p is the matrix of fixed effect covariates, (β)p×1 is the vector of fixed effects, (Zi)ni×q1 is the matrix of random effect covariates, (bi)q1×1 ~ N(0, D) is the vector of random effects, (Wi)ni×q2 is the matrix of class-specific effect covariates, often Wi = Zi, (M)q2×K = (μ1, …, μK) is the matrix of K class effects, with Mci = μk if cik = 1, and (εi)ni×1 ~ N(0, σ2Ini) is the vector of residuals uncorrelated with bi.

Note that Xiβ captures the common fixed effects for the whole population, Wi(Mci) captures the class fixed effect, Zibi captures the random effects or variability among subjects within class, and εi captures the common random effect or variability for the whole population. The class effects covariate W shares no common variable with the fixed effects covariate X, so that no restriction on M is needed to ensure model identifiability. This heterogeneous random effects model is studied by Verbeke and Lesaffre [14] and Lin et al. [10].

2.3. The recurrent event-time submodel

The general recurrent event model of Peña and Hollander 8 is described in this section. Before describing the model, we first introduce a representation of [the] recurrent event data. The data from monitoring the occurrence of the recurrent event can be represented in two equivalent domains: time domain and frequency domain, which is similar to the representation of data in time series analysis.

In survival analysis, the classical or time domain representation of the data is

| (3) |

where Ki = max{j = 1, 2, 3, …: Sij≤τi} is the number of event occurrences over the period of observation for subject i, τi is the censoring or monitoring time for the ith subject, Tij and Sij are the inter-event and calendar time of the occurrence of event, τi − SiKi is the right censored value associated with Ti,Ki+1, and xi(s) is a possibly time-dependent covariate with some components possibly coinciding with some of the covariates associated with the longitudinal biomarker.

It is more convenient to describe the data and make inference for the recurrent event model in the frequency domain than in the time domain. That is, to represent the data in a counting process framework. The frequency domain representation of the data is

| (4) |

where is the number of event occurrences observed over [0, s], is the at-risk (or under-observation) indicator at time s, xi(s) is the possibly time-dependent covariate, is the natural filtration generated by the data, with respect to which the process , xi(·) and are predictable processes, where the process is defined and discussed below.

The differential form of the recurrent event model is given by

| (5) |

where is the class-specific baseline hazard function, is the effective age of the subject i at calendar time s, is the effective number of accumulated events just before time s, ρ(j, α) with ρ(0, α) = 1 is the event accumulation effect function of known form, ψ(·) is a nonnegative link function known form, and ωi is the unobservable frailty variable which is assumed to be gamma distributed.

The frailty random variable ωi is assumed to have mean 1 in order for the model to be identifiable, that is, ωi ~ Gam(θ−1, θ) in (α, β) notation, or ωi ~ Gam(1, θ) in (μ, σ2) notation. The effective age is an observable, predictable, nonnegative piecewise differentiable, and piecewise nondecreasing process. It reflects the effect of interventions such as treatments in biomedical and health settings, and repairs in the engineering and reliability contexts after each event occurrence. The effective age process could be a piecewise linear or nonlinear function of calendar time. The linear effective age process 15 is given by a piecewise linear function , where Aij is the intercept at the repair time and Bij is the aging rate, which presumably can be determined by the experts performing the interventions. One special case of a linear effective age process is minimal repair, , where the performed intervention is minimal and leads to just restarting the unit at an age equal to the age just before the failure. Another special case of linear effective age process is perfect repair, , in which after an event occurrence, a perfect intervention or repair is performed in such a way that the effective age of the unit governing the baseline hazard restarts at zero. Other forms of associate this notion of an effective age process with varied proposals in the literature and demonstrate the generality of this class of models, as described by Peña and Hollander [8].

The effective number of accumulation events just before time s is defined such that it is reset to 0 if a perfect intervention is performed just before time s and equal to otherwise. The function ρ(·; α) represents the effect of accumulating event occurrences on the unit. If an increasing number of event occurrences leads to a weakening of the subject, such as an increasing number of nonfatal heart attacks, then this function will be increasing; whereas if more event occurrences lead to improvement on the subject, such as the discovery of bugs in a computer software, then this function will be decreasing. A simple form for this function is taken to be the exponential function with unknown parameter, ρ(j; α) = αj, j, = 1, 2, 3, …. The underlying baseline hazards , are assumed to come from one parametric family, though the more general case where they come from different parametric families is also possible. This event model is a mixture of survival models that generalizes the model in Lin et al. [10] to the case of recurrent events with intervention but with a parametric specification for the baseline hazards.

2.4. Conditional independence

A reasonable assumption, as argued in [10], made about the relationship between the longitudinal biomarker and recurrent events is CI. Let f be a generic symbol for a probability element of a random process and let be the combined covariates for subject i in the joint model. The CI assumption postulates that

| (6) |

Although the longitudinal biomarker and recurrent event time are correlated, they are independent of each other given the latent class being identified. DeGruttola and Tu [16], Henderson et al. [17] and Lin et al. [10] all assume CI.

3. PARAMETER ESTIMATION

3.1. Likelihood function

Given the baseline hazard governing the counting process model for the recurrent event is parametrically specified, we use a parametric maximum likelihood method to estimate the parameters in the joint model. Let MVNni denote the multivariate normal density of ni dimension, and g(ω, θ) be the density of frailty ω with parameter θ. With f a generic symbol for a probability element for a random process, the log-likelihood of the observed data {}, or simply {}, can be written as

| (7) |

where

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

The multinomial logit probability element (8) can be found, for instance, in Long [18]. The longitudinal biomarker probability element (9) can be found in Verbeke and Molenberghs [19]. The recurrent event probability element (10) can be found, for instance, in Andersen et al. [20].

3.2. The estimation algorithm

We use the EM algorithm [21] to perform maximum likelihood estimation for the latent class joint model. The latent class membership ci, random effect bi in the longitudinal marker submodel, and the frailty ωi in the recurrent event submodel are regarded as missing data. If the number K of latent classes is known, the complete-data log-likelihood for the complete data () is given by

| (11) |

(1) The E-step

Let denote the conditional (posterior) expectation of a random variable x given the observed data. The posterior expectation can be computed as follows:

| (12) |

where and are given in (9) and (10).

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

(2) The M-step

The closed-form updates are given by the following:

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

The updates for frailty variance θ, class-specific baseline hazard parameters ξ, class-specific accumulation effect parameter α, event covariate coefficient γ, which are not in closed form, can be obtained by an optimization procedure such as Newton–Raphson.

(3) Standard errors

Once we get the point estimates of the parameters in the joint model, we adopt the bootstrap method [22] to find the standard errors of the parameter estimates with the bootstrap sample size at least 1000. The bootstrap method is recommended for obtaining standard errors in the latent class mixture model, especially for small data sets.

3.3. Model selection

One of the major considerations with fitting finite mixture models concerns the choice of the number of components or classes K in the mixture model where K has to be inferred from the data. There are two main ways to estimate the order of a finite mixture model based on the likelihood [23]. One way uses the bootstrapped likelihood ratio statistic (LRTS); the other way is through penalized log-likelihood or information criteria. Though the bootstrapped LRTS method can provide an approximate confidence like p-value, it is computationally intensive and challenging in our latent class joint model setting. Therefore, we will adopt the less computationally demanding penalized likelihood criteria approach.

Numerous works in the literature such as Celeux and Soromenho [24], and Leroux [25], Biernacki et al [26, 27] study and compare the penalized information criteria such as Akaike information criterion (AIC) [28], classification likelihood criterion (CLC) [29], Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [30], and integrated classification likelihood criterion with BIC approximation (ICL-BIC) [27] in the mixture model setting. It is observed that AIC is order inconsistent and tends to overestimate the number of components; BIC underestimates the number of components when the model for the component densities is valid and the sample size is not very large and overestimates the number of components when the model for the component densities is not valid; CLC tends to overestimate the number of components when no restriction is placed on the mixing proportions. ICL-BIC inherits the advantages of BIC and CLC, and overcomes the shortcomings of each of them by combining these two criteria together, so we adopt the ICL-BIC criterion here. In the setting of our latent class joint model, let ψ be the true parameters, d be the number of unknown parameters in the joint model, the ICL-BIC criterion is given by

| (24) |

where is the estimated log-likelihood, is the estimated entropy of the fuzzy classification matrix C = (τij), and is the estimated posterior probability of the ith class membership for subject j. From equation (24), we can see that ICL-BIC is the sum of BIC and twice the estimated entropy.

4. SIMULATION STUDY

To validate the estimation procedure, we generated simulated data with sample size n = 200 and the number of latent classes K = 3. The sample size and the number of classes are chosen such that there are enough observations in each class for easier classification and accurate estimation of parameters. The choice of K = 3 also provides an interesting mixture and opportunity for both overestimation and underestimation of the number of components. The baseline hazards for recurrent events are assumed to belong to the most commonly used two parameter Weibull family in survival analysis. The shape and scale parameters of Weibull distribution are denoted by ξ. For instance, ξ11, ξ21 are the shape and scale parameters for class one. The censoring mechanism for the end of study time is the uniform distribution. A linear transformation of ordinary age serves as an effective age function, which includes minimal repair: , and perfect repair: , with a perfect repair probability of 0.6. The perfect repair probability of 0.6 is chosen so that there are about half of minimal repairs and about another half of perfect repairs. The longitudinal markers are generated by three classes of quadratic polynomials in terms of time. The three sub-models share two fixed effect covariates: a continuous variable called measurement and a discrete variable called treatment so that there are both quantitative and qualitative explanatory variables in three submodels.

We consider the joint model with number of classes from K = 1 to 5. Table I summarizes the results of the model selection statistics. We observed that both BIC and ICL-BIC chose the right model of K = 3 for this data set.

Table I.

Information criteria for the simulated data of size n = 200.

| K | Dimension | Log-likelihood | 2Entropy | BIC | ICL-BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | −3715.919 | 0.000 | 7527.207 | 7527.207 |

| 2 | 27 | −3364.964 | 2.650 | 6872.982 | 6875.632 |

| 3 | 36 | −3263.858 | 9.654 | 6718.456 | 6728.110 |

| 4 | 45 | −3257.093 | 9.861 | 6752.610 | 6762.471 |

| 5 | 54 | −3256.014 | 10.967 | 6798.138 | 6809.105 |

Note: K is the number of latent classes, Dimension is the number of parameters to estimate, 2Entropy is twice the entropy with 2 * entropy + BIC = ICL-BIC.

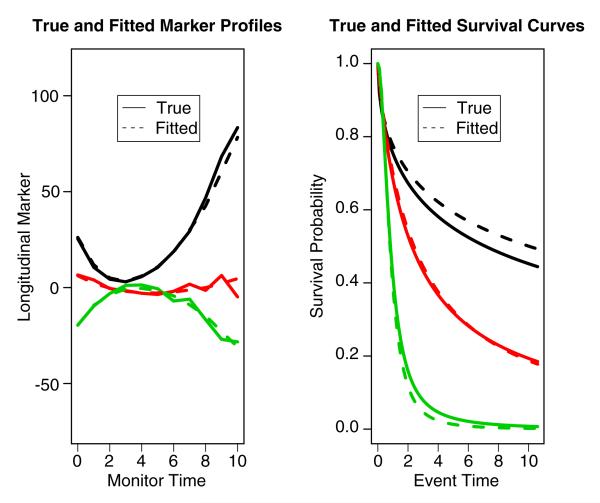

We present the class, biomarker and recurrent event model estimates of the parameters in Table II. The closeness of the true values and the estimated values shows that the estimation procedure works very well. Based on the underlying data and the parameter estimates, we plot the true biomarker profiles and estimated biomarker profiles, the true survival curve and the estimated survival curve in Figure 1. The true biomarker profiles are plotted as the average trend based on the subject membership, while the fitted biomarker profiles are plotted by using the formula with average covariate values in X and W. The survival curves are plotted based on the class-specific baseline hazard and average covariate values. It can be seen that the fits are quite satisfactory.

Table II.

Parameter estimates for the simulated data of size n = 200.

| Para | True | Esti | Std | PL | PU | NL | NU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η 12 | −0.50 | −0.52 | 0.29 | −1.10 | 0.01 | −1.09 | 0.05 |

| η 22 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.25 | 0.20 | 1.18 |

| η 32 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 1.76 | 0.23 | 1.73 |

| η 13 | −0.80 | −0.79 | 0.33 | −1.48 | −0.22 | −1.43 | −0.14 |

| η 23 | 2.00 | 2.14 | 0.34 | 1.65 | 3.00 | 1.46 | 2.81 |

| η 33 | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.45 | −0.17 | 1.55 | −0.22 | 1.55 |

| β 1 | 2.00 | 1.96 | 0.09 | 1.79 | 2.13 | 1.79 | 2.14 |

| β 2 | −1.00 | −1.31 | 0.15 | −1.62 | −1.02 | −1.61 | −1.01 |

| M 11 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 1.40 | 0.80 | 1.39 |

| M 21 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 0.09 | 1.78 | 2.13 | 1.79 | 2.15 |

| M 31 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 0.13 | 2.56 | 3.09 | 2.57 | 3.09 |

| M 12 | −2.00 | −1.94 | 0.17 | −2.28 | −1.59 | −2.28 | −1.60 |

| M 22 | −1.00 | −1.02 | 0.10 | −1.23 | −0.84 | −1.22 | −0.82 |

| M 32 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.79 |

| M 13 | 2.00 | 2.11 | 0.19 | 1.75 | 2.49 | 1.74 | 2.48 |

| M 23 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 1.20 |

| M 33 | −1.50 | −1.56 | 0.14 | −1.83 | −1.29 | −1.84 | −1.29 |

| D 11 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 1.15 | 0.64 | 1.17 |

| D 21 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| D 31 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.76 |

| D 22 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.62 |

| D 32 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.31 |

| D 33 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 0.13 | 0.94 | 1.43 | 0.94 | 1.43 |

| σ 2 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.04 |

| θ | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.02 |

| ξ 11 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.62 |

| ξ 21 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 1.57 | 0.30 | 1.40 |

| ξ 12 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 1.10 |

| ξ 22 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.19 | 0.71 | 1.46 | 0.63 | 1.38 |

| ξ 13 | 2.00 | 2.13 | 0.07 | 2.00 | 2.27 | 1.99 | 2.26 |

| ξ 23 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 1.17 | 0.82 | 1.15 |

| α 1 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.90 |

| α 2 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 1.12 | 0.78 | 1.11 |

| α 3 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 1.26 | 1.05 | 1.26 |

| γ 1 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 1.34 | 0.92 | 1.34 |

| γ 2 | −1.00 | −1.12 | 0.17 | −1.44 | −0.80 | −1.45 | −0.79 |

Note: The columns correspond to true parameters, estimated parameters, and the bootstrap standard errors, percentile confidence lower bound, percentile confidence upper bound, normal approximation confidence lower bound, normal approximation confidence upper bound. The confidence intervals are all 95 per cent confidence intervals. The identifiability constraint (η11, η21, η31) = (0, 0, 0) is not shown in the table. The bootstrap sample size is B = 1000.

Figure 1.

The true and fitted marker profiles and survival functions for the simulated data of size n = 200. The true marker profiles are plotted based on generated marker data. The fitted marker profiles are plotted based on the fitted mean where X and W are the average values of X’s and W’s, respectively. The true and fitted survival curves are plotted by using the true and fitted Weibull parameters and average covariate values.

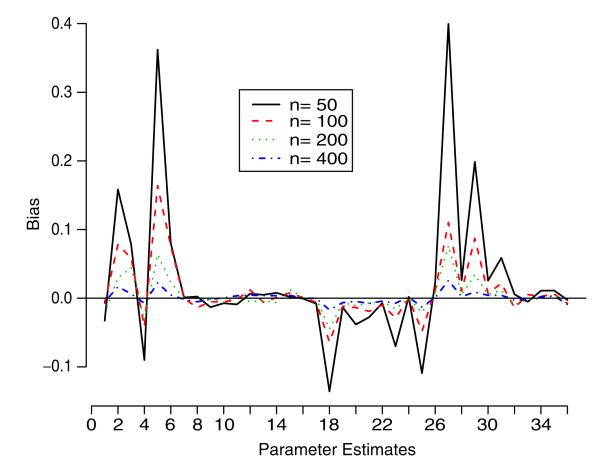

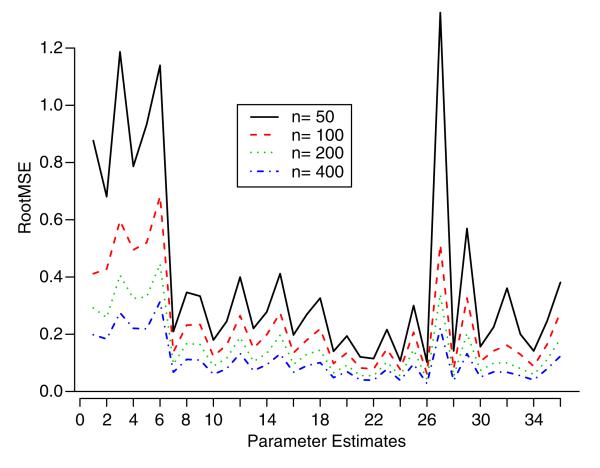

Simulation studies were also performed to numerically examine the properties of the parameter estimators. In particular, we studied the bias, variance, and root-mean-square error (rmse) of the estimators. Using the same model parameter values as in the previous simulation, four different sample sizes {50, 100, 200, 400} were chosen to perform the studies. Graphical summaries of bias and rmse of parameter estimates are given in Figures 2 and 3. It can be seen that as the sample size increases, both the bias and rmse approach zero.

Figure 2.

The bias plot of parameter estimates for the simulation study. The horizontal axis denotes the 36 parameter estimates in the same order as in the first column of Table II.

Figure 3.

The root-mean-square error plot of parameter estimates for the simulation study. The horizontal axis denotes the 36 parameter estimates in the same order as in the first column of Table II.

5. APPLICATION TO EPILEPTIC SEIZURE DATA

5.1. The data and variable description

For illustrative purposes, we apply the joint modeling procedure to a convulsive seizure data set described in Tables I and II of [31]. This study recorded serial blood samples taken at approximately regular intervals during the course of a single day for eight comparatively severe epileptics. All subjects were kept in bed without food during the period of study. Some subjects had seizures during the morning, while others had convulsions during the afternoon or had none throughout the observation period. The serial blood samples were analyzed to determine the concentrations of three lipids in plasma: total fatty acid, lecithin, and cholesterol.

McQuarrie et al. [31] found that there was no consistent relationship between the absolute level of any single lipid fraction and the recurrence of convulsions in those patients who did experience seizures. But they observed that the average lecithin–cholesterol ratio was higher during that part of the day when seizures occurred than during periods when they did not occur. This association of seizures with the higher lecithin–cholesterol ratio motivates us to use lecithin-cholesterol ratio as a longitudinal marker with the seizures as the recurrent event. Because of discrepancies among the lecithin, cholesterol and lecithin-cholesterol ratio levels as reported in Tables I and II of [31], we use the lecithin and cholesterol levels recorded there and compute the ratio directly. Additionally, patient 5 was noted to experience petit mal seizures, but because no occurrence times are provided, we record no events for this patient.

The plasma lipid levels are observed at five to seven time points during the day. The first sample times vary from 9:30 AM to 10:20 AM among the subjects. We treat these first samples as baseline readings, and hence express the subsequent sample and seizure times in hours since the baseline sample time. All seizures occurring before the baseline sample times are excluded. We summarize this time transformed data in Tables III and IV.

Table III.

Plasma lipids and seizure times for patients 1–4.

| ID | Sample time (h) |

Seizure time (h) |

Fatty acid (mgm per cc) |

Lecithin (mgm per cc) |

Cholesterol (mgm per cc) |

LC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.00 | 1.78 | 2.93 | 1.97 | 1.69 | 1.17 |

| 1 | 1.92 | 4.00 | 3.11 | 1.97 | 1.78 | 1.11 |

| 1 | 3.92 | 3.02 | 1.86 | 1.82 | 1.02 | |

| 1 | 4.08 | 3.34 | 1.97 | 1.67 | 1.18 | |

| 1 | 6.00 | 2.80 | 0.75 | 1.46 | 0.51 | |

| 1 | 8.00 | 3.40 | 1.53 | 1.83 | 0.84 | |

| 1 | 10.00 | 3.85 | 2.00 | 1.89 | 1.06 | |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 3.74 | 1.97 | 1.76 | 1.12 |

| 2 | 0.47 | 1.80 | 3.19 | 1.82 | 1.73 | 1.05 |

| 2 | 1.83 | 3.21 | 1.78 | 1.65 | 1.08 | |

| 2 | 3.83 | 3.39 | 1.53 | 1.69 | 0.91 | |

| 2 | 5.92 | 3.19 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 0.88 | |

| 2 | 8.00 | 3.28 | 1.31 | 1.80 | 0.73 | |

| 2 | 9.83 | 3.18 | 1.30 | 1.73 | 0.75 | |

| 3 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 2.62 | 1.64 | 1.33 | 1.23 |

| 3 | 2.00 | 2.75 | 2.88 | 1.84 | 1.44 | 1.28 |

| 3 | 4.00 | 2.64 | 1.45 | 1.36 | 1.07 | |

| 3 | 4.83 | 2.56 | 1.60 | 1.42 | 1.13 | |

| 3 | 6.83 | 2.67 | 1.47 | 1.42 | 1.04 | |

| 3 | 8.83 | 2.59 | 1.35 | 1.41 | 0.96 | |

| 3 | 10.83 | 2.57 | 1.11 | 1.47 | 0.76 | |

| 4 | 0.00 | 3.09 | 1.75 | 1.55 | 1.13 | |

| 4 | 2.00 | 3.03 | 1.64 | 1.46 | 1.12 | |

| 4 | 4.00 | 2.54 | 0.82 | 1.20 | 0.68 | |

| 4 | 6.05 | 2.80 | 0.97 | 1.32 | 0.73 | |

| 4 | 8.05 | 2.67 | 0.71 | 1.29 | 0.55 | |

| 4 | 10.05 | 2.71 | 1.06 | 1.33 | 0.80 |

Note: LC ratio is lecithin–cholesterol ratio.

Table IV.

Plasma lipids and seizure times for patients 5–8.

| ID | Sample time (h) |

Seizure time (h) |

Fatty acid (mgm per cc) |

Lecithin (mgm per cc) |

Cholesterol (mgm per cc) |

LC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.00 | 3.19 | 1.60 | 1.59 | 1.01 | |

| 5 | 1.02 | 3.28 | 1.60 | 1.51 | 1.06 | |

| 5 | 3.18 | 2.69 | 1.57 | 1.63 | 0.96 | |

| 5 | 5.18 | 3.13 | 1.71 | 1.65 | 1.04 | |

| 5 | 7.18 | 2.88 | 0.95 | 1.53 | 0.62 | |

| 5 | 9.18 | 2.85 | 1.34 | 1.63 | 0.82 | |

| 5 | 11.18 | 2.83 | 1.45 | 1.58 | 0.92 | |

| 6 | 0.00 | 3.61 | 1.92 | 1.98 | 0.97 | |

| 6 | 1.98 | 3.76 | 2.06 | 2.31 | 0.89 | |

| 6 | 4.00 | 2.97 | 1.73 | 1.95 | 0.89 | |

| 6 | 6.02 | 3.60 | 1.55 | 1.92 | 0.81 | |

| 6 | 8.93 | 3.30 | 2.01 | 2.13 | 0.94 | |

| 7 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 3.10 | 1.37 | 1.11 | 1.23 |

| 7 | 0.62 | 4.43 | 5.51 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.04 |

| 7 | 1.47 | 5.27 | 1.42 | 1.17 | 1.21 | |

| 7 | 3.47 | 2.84 | 1.45 | 1.21 | 1.20 | |

| 7 | 5.47 | 2.91 | 1.53 | 1.15 | 1.33 | |

| 7 | 7.80 | 2.49 | 1.45 | 1.32 | 1.10 | |

| 7 | 9.80 | 2.58 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.85 | |

| 8 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 3.11 | 1.47 | 1.30 | 1.13 |

| 8 | 3.73 | 3.65 | 3.71 | 1.67 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| 8 | 5.40 | 5.37 | 3.27 | 1.53 | 1.41 | 1.09 |

| 8 | 5.98 | 7.15 | 2.87 | 1.64 | 1.36 | 1.21 |

| 8 | 7.98 | 2.94 | 1.26 | 1.29 | 0.98 | |

| 8 | 9.98 | 3.14 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.20 |

Note: LC ratio is the lecithin–cholesterol ratio.

The baseline fatty acid is used as fixed covariates X in the marker model. The baseline fatty acid and lecithin-cholesterol ratio are included as covariates v in the logit model and as x in the recurrent event model. The intercept, linear and quadratic terms of time t are included in the class effect matrix W. We include only the individual random intercept in Z of the marker model, since the individual time trend is not significant compared with random intercept terms and class effect time trend terms. We first assume a minimal intervention and then assume a perfect intervention for the intervention effect after each occurrence of the seizure.

5.2. Estimation of epilepsy data

Under assumption of minimal intervention following each seizure, with effective age given by , we fit the joint model with K = 1–5 classes to the epilepsy data. The information criteria are given in Table V. The estimated entropy for each model is close to its minimum value of zero, so the components of the mixture are well separated for all five models. ICL-BIC chooses the two-class model. When, instead, perfect intervention is assumed following each seizure, ICL-BIC chooses the one-class model. The parameter estimates and bootstrap standard errors under the two intervention modes are given in Table VI.

Table V.

Information criteria for the epilepsy data under minimal intervention.

| K | d | d log n | 2Entropy | −2l | BIC | ICL-BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 24.95 | 0.00E+00 | 12.15 | 37.10 | 37.10 |

| 2 | 21 | 43.67 | 9.33E−04 | −36.16 | 7.51 | 7.51 |

| 3 | 30 | 62.38 | 4.78E−04 | −38.38 | 24.01 | 24.01 |

| 4 | 39 | 81.10 | 9.94E−04 | −40.12 | 40.97 | 40.97 |

| 5 | 48 | 99.81 | 3.82E−05 | −70.59 | 29.23 | 29.23 |

Note: K is the number of latent classes, d is the number of parameters to estimate, 2Entropy is twice the estimated entropy, −2l is negative twice of the estimated log-likelihood.

Table VI.

Parameter estimates for the epilepsy data under minimal intervention and perfect intervention.

| Minimal intervention |

Perfect intervention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Term | Para | Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Standard error |

| Class | Intercept (2) | η 12 | 3287.008 | 13.532 | ||

| Fatty acid (2) | η 22 | −349.308 | 33.913 | |||

| LC ratio (2) | η 32 | −1950.578 | 19.749 | |||

| Marker | Fatty acid | β 1 | −0.071 | 0.076 | −0.136 | 0.103 |

| Intercept (1) | M 11 | 1.286 | 0.416 | 1.407 | 0.330 | |

| Linear time (1) | M 21 | −0.029 | 0.010 | −0.028 | 0.005 | |

| Quadratic time (1) | M 31 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Intercept (2) | M 12 | 1.042 | 0.268 | |||

| Linear time (2) | M 22 | −0.027 | 0.009 | |||

| Quadratic time (2) | M 32 | 0.006 | 0.003 | |||

| Event | Shape (1) | ξ 11 | 1.251 | 0.714 | 0.758 | 0.473 |

| Scale (1) | ξ 21 | 0.014 | 0.081 | 157.527 | 2471.980 | |

| Shape (2) | ξ 12 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Scale (2) | ξ 22 | 1.510 | 0.000 | |||

| Accumulation (1) | α 1 | 0.273 | 0.170 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Accumulation (2) | α 2 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Fatty acid | γ 1 | 0.214 | 1.047 | −0.320 | 1.032 | |

| LC ratio | γ 2 | −5.371 | 6.182 | 2.923 | 3.213 | |

Note: LC ratio is the lecithin–cholesterol ratio. Standard errors are bootstrap estimates with bootstrap sample sizes of 1000.

Under minimal intervention, subjects 4–6 are classified into class 2 while other subjects are classified into class 1. This classification is scientifically meaningful since subjects 4–6 have no seizures during the observational period and have average lecithin-cholesterol ratio relatively low, while the other subjects all have multiple seizures and relatively high average lecithin–cholesterol ratio.

Under perfect intervention, that is, if we assume the seizure event itself renews the patient perfectly, then only one class is identified by ICL-BIC. It seems that the intervention mode assumption has some impact on the classification of the subjects. Recalling that no intervention is performed following seizures and that patients are kept in bed with no food, the minimal intervention effective age formulation is more reasonable. In further comparing the fits, we note the accumulation effect coefficient (α) defaults to one for lack of accumulating events in both the nonevent class of the two-class minimal intervention model fit and the one-class perfect intervention model fit.

Based on 95 per cent bootstrap confidence intervals, the baseline fatty acid in the marker model and the recurrent event model are not significant under both intervention modes while the baseline lecithin–cholesterol ratio in the recurrent event model is significant under minimal intervention and insignificant under perfect intervention. This result confirms the observation made in McQuarrie et al. [31]. The bootstrap standard errors for some coefficients in the recurrent event model are large compared with their point estimates. The major reason for this is that there are only a total of eight subjects where three subjects have no events while the other five subjects have two events on average. We have nine event model parameters to estimate in the two-class model and six event model parameters to estimate in the one-class model. This is not true for longitudinal marker model parameters. In the marker model, there are about seven marker values observed for each of the eight subjects to estimate about the same number of parameters as in the event model. So we are not expected to attach high confidence to the precision of point estimates in the event model relative to point estimates in the marker model for this small data set. However, this data set illustrates how the latent class joint model for marker and recurrent events can be used to classify patients and capture potential subpopulation structure that may be induced by unobserved factors such as genotype, personal behavior and dietary habits.

In practice, we recommend there be at least three observed marker values per subject and the total number of events be at least 4 times of the number of parameters in the recurrent event model. The variations of recurrent event model parameter estimates are related to the number of events per subject, point estimates of baseline hazard, censoring mechanism, bootstrapping, and convergence of EM algorithm. Generally speaking, even for small data set this model can provide decent classification of subjects since both the marker data and recurrent event data are used for the purpose of categorization. But for estimation of parameters in marker and recurrent event models, there should be enough marker observations and events to ensure precise estimates of parameters in each model, especially for recurrent event model.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper provides a new joint model for a longitudinal biomarker and recurrent event that incorporates many of the unique features inherent in such data. In particular, the model accommodates the effects of interventions that are performed after each event occurrence, the weakening or strengthening impact on the subject of accumulating event occurrences, the effect on the rate of event occurrence of possibly time-dependent covariates, and correlation among and between biomarker readings and event occurrences within each subject. The association between the biomarker and recurrent event outcome processes is induced through the latent class structure, which, secondarily, also serves to handle an underlying heterogeneous population.

We used penalized information criteria to select the number of latent classes and performed inference by maximum likelihood using the EM algorithm and bootstrap method. The results of the simulation studies pertaining to the bias and variance appear to be in agreement with the consistency and asymptotic normality properties of maximum likelihood estimators, which we do not discuss here.

Our model utilizes the full information from the biomarker and recurrent event data, in contrast to a number of alternatives. In this setting, for example, pattern mixture models [32, 33] would represent the biomarker conditional upon the event occurrence pattern, and selection models [34, 35] and related joint models [36, 37] typically consider the event hazard conditional upon the current, possibly imputed, biomarker value.

An important aspect of modeling the effect of interventions is recording the data necessary to determine the intervention mode or the effective age process, , in (5) after the intervention. This information may generally be available in reliability settings, where perfect and imperfect repairs are objectively evaluated, but often lacking except in very subjective forms in the biomedical context. Gonzalez et al. [38] provide some guidance concerning for the setting of cancer relapses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jun Han acknowledges the research support provided by FY07 Research Initiation Grant of Georgia State University, NSF Grant DMS 0102870, NIH Grant GM056182, and the USC/MUSC Collaborative Research Program. Elizabeth Slate acknowledges the research support provided by NSF Grant DMS 0604666, NIH Grant CA077789, NIH COBRE Grant RR17696, DAMD Grant 17-02-1-0138 and the USC/MUSC Collaborative Research Program. Edsel Peña acknowledges the research support provided by NSF Grant DMS 0102870, NIH Grant GM056182, NIH COBRE Grant RR17698, and the USC/MUSC Collaborative Research Program. We also thank two reviewers and the editor for carefully reading the manuscript and for providing us with invaluable comments and suggestions which led to substantial improvements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biomarkers Definitions Working Group Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2001;69:89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming TR, Prentice RL, Pepe MS, Glidden D. Surrogate, auxiliary endpoints in clinical trials, with potential applications in cancer, AIDS research. Statistics in Medicine. 1994;13:955–968. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780130906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalbfleisch JS, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2nd edn Wiley; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewell NP, Nielsen JP. A framework for consistent prediction rules based on markers. Biometrika. 1993;80(1):153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu CJ, Meeker WQ. Using degradation measures to estimate a time-to-failure distribution. Technometrics. 1993;35:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitmore GA. Estimating degradation by a Wiener diffusion process subject to measurement error. Lifetime Data Analysis. 1995;1:307–319. doi: 10.1007/BF00985762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peña EA, Strawderman RL, Hollander M. Nonparametric estimation with recurrent event data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96(456):1299–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peña EA, Hollander M. Models for recurrent events in reliability and survival analysis. In: Soyer R, Mazzuchi T, Singpurwalla N, editors. Mathematical Reliability An Expository Perspective. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 2004. pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peña EA, Slate EH, Gonzalez J. Semiparametric inference for a general class of models for recurrent events. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2007;137:1727–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.jspi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin H, Turnbull BW, McCulloch CE, Slate EH, Clark LC. Latent class models for joint analysis of longitudinal biomarker and event process data: application to longitudinal prostate-specific antigen readings and prostate cancer. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97(457):53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson GL, Fleming TT. Model misspecification in proportional hazard regression. Biometrika. 1995;82:527–541. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H, McCulloch CE, Rosenheck RA. Latent pattern mixture models for informative intermittent missing data in longitudinal studies. Biometrics. 2004;60:295–305. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsiatis AA, Davidian M. Joint modeling of longitudinal and time-to-event data: an overview. Statistica Sinica. 2004;14:793–818. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbeke G, Lesaffre E. A linear mixed-effects model with heterogeneity in the random-effects population. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorado C, Hollander M, Sethuraman J. Nonparametric estimation for a general repair model. The Annals of Statistics. 1997;25:1140–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeGruttola V, Tu XM. Modeling progression of CD4+ lymphocyte count and its relationship to survival time. Biometrics. 1994;50:1003–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson R, Diggle P, Dobson A. Joint modeling of longitudinal measurements and event time data. Biostatistics. 2000;1:465–480. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long JS. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen PK, Borgan Ø , Gill RD, Keiding N. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes. Springer; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Annals of Statistics. 1979;7:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLachlan GJ, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Classification Journal. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leroux BG. Consistent estimation of a mixing distribution. Annals of Statistics. 1992;20:1350–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biernacki C, Celeux G, Govaert G. An improvement of the NEC criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Pattern Recognition Letters. 1999;20:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biernacki C, Celeux G, Govaert G. Assessing a mixture model for clustering with the integrated completed likelihood. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 2000;22(7):719–725. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biernacki C, Govaert G. Using the classification likelihood to choose the number of clusters. Computing Science and Statistics. 1997;29:451–457. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McQuarrie I, Husted C, Bloor WR. The lipids of the blood plasma in epilepsy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1933;12(2):255–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI100500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little RJA. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1993;88:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little RJA, Wang Y. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data with covariates. Biometrics. 1996;52:98–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diggle PJ, Kenward MG. Informative drop-out in longitudinal data analysis. Applied Statistics. 1994;43(1):49–93. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Zahner GEP. Multivariate logistic models for incomplete binary responses. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faucett CL, Thomas DC. Simultaneously modeling censored survival data and repeatly measured covariates: a Gibbs sampling approach. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;16:1663–1668. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960815)15:15<1663::AID-SIM294>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wulfsohn MS, Tsiatis AA. A joint model for survival and longitudinal data measured with error. Biometrics. 1997;53:330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez JR, Peña EA, Slate EH. Modelling intervention effects after cancer relapses. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:3959–3975. doi: 10.1002/sim.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]