Abstract

INTRODUCTION

AML is the most common form of leukemia in adults. In rare circumstances AML may present in the form of extra-medullary disease. Gallbladder infiltration with myeloblasts is rare and only a few cases exist in the literature describing this entity.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We present a rare case of AML relapse in the form of extramedullary infiltration of the gallbladder in a 50-year-old male patient. The leukemic infiltration presented as symptomatic cholecystitis and sepsis. A laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed and the gallbladder was pathologically examined. Histopathologic examination demonstrated multiple scattered, highly atypical single cells admixed with some plasma cells, small lymphocytes and macrophages consistent with leukemic infiltration. The abnormal cells demonstrated immunohistochemical staining for CD68, CD33 and CD117. The patient did well post-operatively but the relapse precluded him from bone marrow transplantation.

DISCUSSION

Although AML is relatively common, 3 cases per 100,000 population, extramedullary disease in the form of gallbladder infiltration is exceedingly rare. An extensive review of the literature revealed only four cases of myeloid infiltration of the gallbladder. To our knowledge this is the only case of relapsing disease in the form of gallbladder infiltration presenting as symptomatic cholecystitis in a pre-bone marrow transplantation patient.

CONCLUSION

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion of atypical manifestations of AML when managing refractory sepsis. Extramedullary manifestations of AML in the form of gallbladder infiltration must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with a history of myeloid malignancies and for patients whom fail conventional non-operative management.

Keywords: Cholecystitis, Acute myeloid leukemia, Gallbladder, Cholecystectomy

1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia is a hematological malignancy characterized by a variable clinical course. Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia may present with myeloid sarcoma, leukemic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract or mediastinum, and in rare circumstances, infiltration of the biliary system with myeloid cells. We report a case of a patient who presented with acute cholecystitis as a manifestation of his acute myeloid leukemia through infiltration of the gallbladder wall with immature myeloid lineage cells.

2. Case

A 50-year-old male receiving care at our institution for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in his second morphological free state, presented to the Emergency Department with worsening diarrhea, intermittent nausea and vomiting, fever, right upper quadrant pain, and decreased oral intake in the setting of a 2-month history of chronic cholecystitis. Initial laboratory investigations revealed pancytopenia (hemoglobin 98 g/L [120–160 g/L], platelets 17 × 109/L [150–400 × 109/L], WBC 1.1 × 109/L [4.0–11.0 × 109/L] with 0% blasts), and an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 218 U/L [40–150 U/L] with a total bilirubin of 28 μmol/L [≤22 μmol/L].

He was initially diagnosed with AML in May 2012, which had transformed from chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with normal cytogenetics. As a result, he was started on induction therapy with standard-dose Cytarabine and Idarubicin and achieved a morphological free state by June 2012. Unfortunately, in November 2012, he was found to have a relapse of his AML that was confirmed by bone marrow biopsy (10–12% blasts), peripheral blood smear (5–6% blasts), flow cytometry and an elevated LDH of 638 U/L [125–220 U/L]. As a result, he underwent re-induction therapy with NOVE-HiDAC (Mitoxantrone, Etoposide and high-dose Cytarabine) in December 2012, and once again achieved a morphological free state without count recovery. He was subsequently accepted for allogenic bone-marrow transplant, with a tentative date of June 2013.

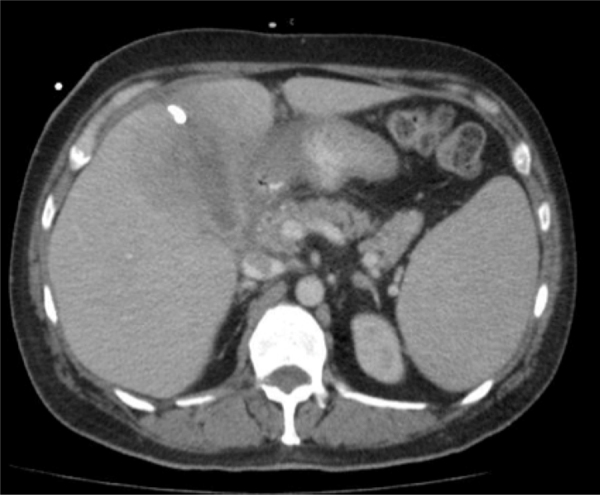

While awaiting a matched donor for bone-marrow transplantation, he was admitted for cholecystitis and febrile neutropenia, the former of which was managed conservatively with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (Piperacillin-Tazobactam) given his thrombocytopenia and perioperative risk profile. Six days following discharge, he was readmitted with increasing nausea, vomiting, fever, and RUQ pain. In addition to a second course of antibiotics (Vancomycin, Colistin, Flagyl and Voriconazole), a percutaneous cholecystostomy tube was also placed for source control. Computerized axial tomography (CAT) of the abdomen was performed and demonstrated gallbladder distension and thickening consistent with cholecystitis. However, there was no evidence of peri-cholecystic fluid or associated inflammatory changes around the gallbladder. Dilation of intrahepatic ducts and common bile duct were not seen (Fig. 1). He was discharged home with improvements in his abdominal pain and oral intake; however, soon after discharge, he had a relapse of his cholecystitis-related symptoms and was once again managed conservatively and re-admitted to hospital. A percutaneous contrast study evaluating drain placement was performed and demonstrated persistent obstruction of the cystic duct. For these reasons, the cholecystostomy tube was left in situ.

Fig. 1.

Computed axial tomography (CAT) demonstrating thickening of the gallbladder with surrounding edema and inflammation.

Approximately 7 weeks after his initial presentation, surgical consultation was sought in order to determine his eligibility to undergo an elective cholecystectomy for definitive source control, a prerequisite for bone-marrow transplantation. Although definitive surgical management was ultimately delayed secondary to subsequent hospital admissions for febrile neutropenia and cholecystitis, he eventually underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy approximately 3 months following his initial presentation.

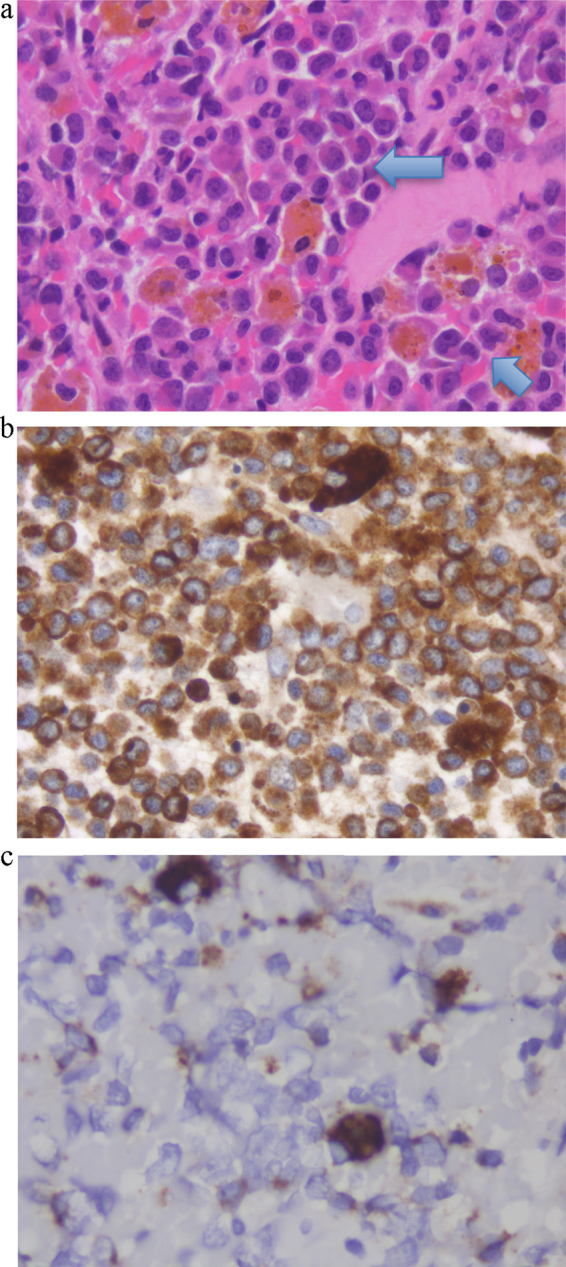

Intra-operatively, there were extensive adhesions in the right upper quadrant. During the dissection, the gallbladder was entered with subsequent extrusion of purulent and necrotic debris. Overall, the patient tolerated the procedure well and there were no intraoperative complications. Macroscopically the resected gallbladder showed a tan colored fibrinous exudate and a completely necrotic back wall. Histopathologic examination of the specimen demonstrated multiple scattered, highly atypical single cells admixed with some plasma cells, small lymphocytes and macrophages consistent with leukemic infiltration (Fig. 2a). The abnormal cells demonstrated immunohistochemical staining for CD68 (KP1), CD33 and CD117, however, CD34 was not increased (Fig. 2b and c). These findings were consistent with the manifestation of his previously known myelomonocytic leukemia, and the second relapse of his disease. A peripheral blood smear and bone-marrow aspirate and biopsy were conducted. While the peripheral blood film demonstrated pancytopenia and polychromasia, the bone marrow biopsy was consistent with hypercellularity and granulocytic hyperplasia. Flow cytometry analysis showed 15% of cells in the lymphocyte region, 5% in the monocyte region, and 30% in the region for granulopoiesis. CD34+ cells comprised approximately 2.5% of bone marrow cells and were positive for CD117, CD13 and variably for CD33. Furthermore, the CD34+ cells showed aberrant phenotype with decreased CD45 expression and positivity for CD7 suggesting presence of the residual disease in the bone marrow.

Fig. 2.

(a) Hematoxylin–Eosin stained section from gallbladder wall showing diffuse infiltrates of mononuclear cells with irregular nuclei and some with prominent nucleoli. Scattered lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages are also present. (b) The majority of cells stain positive for CD68 KP-1 epitope, which is positive not only in macrophages but also in myeloid and monocytic precursors.8 (c) Only rare cells stained positive for CD68-R PGM-1 epitope, which is more macrophage specific.9

Collectively, these findings suggested extramedullary relapse of the patient's known AML despite two cycles of induction therapy. The presence of disease activity precluded him from receiving bone-marrow transplantation due to the risk associated with additional systemic chemotherapy. The patient agreed that he would likely not be able to tolerate further chemotherapy and the goal of care was shifted to best supportive care. At the time of last clinic visit (5 months following surgery) the patient had no further cholecystitis-like symptoms but continues to be seen weekly at our institution's transfusion clinic for management of his pancytopenia.

3. Discussion

In adults, AML is the most common form of acute leukemia, with an incidence of approximately 3 cases per 100,000 population.1 AML is characterized by clonal proliferation of immature myeloid cells that aggressively take over the bone marrow and suppress normal hematopoiesis. As a result, patients present clinically with symptoms related to pancytopenia (fatigue, fever, petechiae, etc.), organomegaly (secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis) and/or bone pain. In rare circumstances (<1% of cases), AML may present as extramedullary disease in the form of a myeloid sarcoma involving the skull, skin, lymph nodes, or axial skeleton or it may involve the gastrointestinal tract, orbit, and/or mediastinum.2,3 Gallbladder infiltration with myeloblasts, however, is exceptionally rare and only a few case reports exist in the literature describing this clinical entity.4–7

This case illustrates the relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in the form of gallbladder wall infiltration, causing symptomatic cholecystitis, and the first case to our knowledge of AML relapse in the form of symptomatic gallbladder infiltration in a patient awaiting bone marrow transplant.

A comprehensive search strategy was devised with experienced information specialists at the University Health Network Library. A combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and relevant text words related to leukemia and gallbladder pathology were utilized. Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid Embase were searched for relevant citations between 1946 and 2013. No language restriction was applied. The title and abstract of the total yield of citations were screened for potential eligibility. The abstract and/or full texts of the potentially eligible citations were obtained for further review, and those that did not meet the selection criteria were excluded. Ultimately, the search yielded only four relevant case reports of myeloid cell leukemic involvement in the gallbladder (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature review summary of myeloid infiltration of gallbladder.

| Age/sex | Malignancy status prior to presentation | Presentation | Surgical approach | BMBa or PBSb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimizu et al. (2006) | 59, M | MDS | Cholecystitis | Open cholecystectomy | AML |

| Bartley et al. (2006) | 63, F | None | Back pain | Open cholecystectomy | Negative |

| Ojima et al. (2005) | 33, M | None | Jaundice | Hepatopancreato-duodenectomy | Negative |

| Bloom et al. (2002) | 49, M | None | Cholecystitis | Open cholecystectomy | AML |

| Current case | 50, M | AML in remission | Cholecystitis | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | AML relapse |

BMB – bone marrow biopsy.

PBS – peripheral blood smear.

Three cases corresponded to myeloid infiltration of the gallbladder as the primary manifestation of disease without involvement of the bone marrow,4–6 whereas one occurred in the setting of myelodysplastic syndrome with progression to acute leukemia.7 Although cholecystitis was diagnosed in each of these patients, the underlying etiology and clinical presentation differed quite significantly. In one case, the patient presented with widespread extra-medullary myeloid sarcoma and incidental gallbladder involvement,4 while in another case, the patient presented with jaundice and was found to have a gallbladder mass.5

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion of atypical manifestations of AML when managing refractory sepsis. In this particular example, the persistent symptoms associated with acute cholecystitis continued in spite of parenteral antibiotics and biliary decompression. Failure of conventional non-operative management was an indication that the etiology of this disease was related to gallbladder leukemic infiltration rather than gallstones alone. Early recognition of the patient's AML may have resulted in a change in management with aggressive, early surgical intervention. While the patient's candidacy for bone marrow transplantation may not have changed, early diagnosis may have improved patient counseling and streamlined the patient care journey.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Authors contributions

AA, JR, MJ, and SS participated in the acquisition and analysis of data, literature review, and writing of the manuscript. TJ, AO, FQ, AP were involved in the medical care of the patient, drafting of the manuscript, and acquisition and analysis of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marina Englesakis from the University Health Network Library for supporting the review of the literature.

Key learning points

-

•

Extramedullary relapse of AML in the form of gallbladder infiltration is rare.

-

•

Gallbladder infiltration with myeloblasts should be considered in the differential for cholecystitis.

-

•

Clinicians must maintain a high-index of suspicion of atypical manifestations of AML when managing refractory sepsis.

-

•

Patients with a known history of AML whom present with cholecystitis refractory to medical management may benefit from earlier surgical intervention.

Contributor Information

Arash Azin, Email: Arash.Azin@mail.utoronto.ca.

Jennifer M. Racz, Email: Jennifer.Racz@gmail.com.

M. Carolina Jimenez, Email: MCarolina.Jimenez@uhn.ca.

Supreet Sunil, Email: Supreet.Sunil@mail.utoronto.ca.

Anna Porwit, Email: Anna.Porwit@uhn.ca.

Timothy Jackson, Email: Timothy.Jackson@uhn.ca.

Allan Okrainec, Email: Allan.Okrainec@uhn.ca.

Fayez Quereshy, Email: Fayez.Quereshy@uhn.ca.

References

- 1.Sant M., Allemani C., Tereanu C., De Angelis R., Capocaccia R., Visser O. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood. 2010;116(November (19)):3724–3734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dores G.M., Devesa S.S., Curtis R.E., Linet M.S., Morton L.M. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001–2007. Blood. 2012;119(January (1)):34–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neiman R.S., Barcos M., Berard C., Bonner H., Mann R., Rydell R.E. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer. 1981;48(September (6)):1426–1437. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810915)48:6<1426::aid-cncr2820480626>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartley A.N., Nelson C.L., Nelson D.H., Fuchs D.A. Disseminated extramedullary myeloid tumor of the gallbladder without involvement of the bone marrow. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(January (1)):65–68. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ojima H., Hasegawa T., Matsuno Y., Sakamoto M. Extramedullary myeloid tumour (EMMT) of the gallbladder. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(February (2)):211–213. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom S.H., Coad J.E., Greeno E.W., Ashrani A.A., Hammerschmidt D.E. Cholecystitis as the presenting manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia: report of a case. Am J Hematol. 2002;70(July (3)):254–256. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu T., Tajiri T., Akimaru K., Arima Y., Yokomuro S., Yoshida H. Cholecystitis caused by infiltration of immature myeloid cells: a case report. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73(April (2)):97–100. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warnke R.A., Pulford K.A., Pallesen G., Ralfkiaer E., Brown D.C., Gatter K.C. Diagnosis of myelomonocytic and macrophage neoplasms in routinely processed tissue biopsies with monoclonal antibody KP1. Am J Pathol. 1989;135(December (6)):1089–1095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falini B., Flenghi L., Pileri S., Gambacorta M., Bigerna B., Durkop H. PG-M1: a new monoclonal antibody directed against a fixative-resistant epitope on the macrophage-restricted form of the CD68 molecule. Am J Pathol. 1993;142(May (5)):1359–1372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]