Abstract

Granuloma inguinale (GI) is an acquired chronic, slowly progressive, mildly contagious disease of venereal origin, characterized by granulomatous ulceration of the genitalia and neighboring sites, with little or no tendency to spontaneous healing caused by Klebsiella (Calymmatobacterium) granulomatis. A 55-year-old male presented with fissured, foul smelling, fungating growth over prepuce with phimosis mimicking squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) without lymphadenopathy. It started with painless papulonodular showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, infiltration in dermis, acanthosis and vacuolated macrophages suggestive of GI and not showing any histopathological features of SCC. Patient was successfully treated by giving cotrimoxazole twice a day for 21 days. Here, we presented a case of GI mimicking SCC of penis, which was diagnosed on basis of histopathology and treated with excision followed by medical therapy with cotrimoxazole.

Keywords: Granuloma inguinale, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, squamous cell carcinoma of penis

INTRODUCTION

Granuloma inguinale (GI) (donovanosis) is an acquired chronic, slowly progressive, mildly contagious disease of venereal origin, caused by Klebsiella (Calymmatobacterium) granulomatis a Gram-negative encapsulated rod characterized by granulomatous ulceration of the genitalia and neighboring sites, with little or no tendency to spontaneous healing.

The first description of donovanosis is attributed to McLeod, Professor of Surgery at the Medical College of Calcutta, India, in 1882.[1]

The first use of the term GI is not known, but is believed to be derived from the anatomic description as follows: Granuloma indicates a growth of granulation tissue, and inguinale indicates involvement of the groin region. Amongst the numerous nomenclatures suggested for this disease, donovanosis was proposed in 1950 to honor Donovan, who noted the characteristic Donovan bodies in macrophages and epithelial cells of the stratum malpighii.[2,3]

Rajam and Rangiah found carcinoma, either as a complication of or a sequel to long-standing donovanosis, to be a rare occurrence seen in 0.25% of 2000 cases.[2]

Batla et al. in their study have reported cutaneous metastases of rectal mucinous adenocarcinoma mimicking as GI.[4]

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of penis is a malignant growth found on the skin or in the tissues of the penis usually originating in the glans or foreskin. It accounts for <1% of cancers in males. It is more common in 6th and 7th decade.[5]

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old, otherwise healthy male had 5 years history of multiple painless papulo nodular lesions on the penis. The nodular lesions slowly evolved and coalesced to form red ulcerated growth over the last 2 months. Physical examination revealed multiple fungating, nontender, coalesced ulcers (2 cm × 1 cm) over prepuce with granulomatous base, and was associated with foul smelling discharge and phimosis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Multiple fungating, coalesced ulcerative growths with phimosis

There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patient had complaints of burning micturition since last 1 month. There was no h/o significant weight loss, fever or any other complaints. Partner's clinical history and examination was inconsequential.

The rest of the physical examination and routine blood and urine analysis including serotesting for syphilis and HIV were unremarkable.

The above clinical picture was suggestive of SCC of penis.

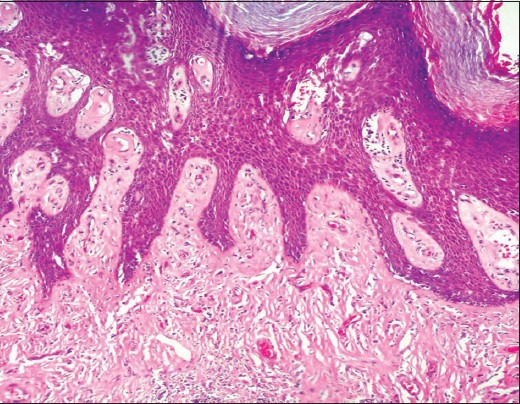

Excisional biopsy was performed and histopathological examination revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and acanthosis along with papillary hyperplasia and downward proliferation of mature squamous cells with smooth contours (pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia). The underlying subepithelial tissue showed dilated lymphatics and congested vessels, deposits of chronic inflammatory cells and vacuolated macrophages [Figure 2]. The above findings and no features of malignancy confirmed the diagnosis of GI.

Figure 2.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and vacuolated macrophages (×100)

Patient was treated with cotrimoxazole (800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim) twice a day for 21 days. Posttreatment clinical picture was very satisfying [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Complete resolution 3 weeks post treatment

DISCUSSION

GI is caused by Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, a Gram-negative rod. Current literature proposes to reclassify this organism as K. granulomati based on more detailed analysis now available.[6] The name has been changed after sequencing the phoE and 165 ribosomal ribonucleic acid genes and demonstrating close homology with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis.[7]

The incubation period for GI is uncertain, ranges between 1–360 days, 3–40 days, 14–28 days, and 17 days.[8] This wide range is probably multi-factorial and may reflect either late presentation and denial or nonsexual transmission.

GI primarily affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the genital and perianal region. The penis, scrotum, and glans are the most commonly affected sites in males; and the labia and perineum are the most commonly affected in females. Vaginal and cervical involvement has also been reported and sometimes mistaken for SCC.[7]

The primary lesion may be noted as a firm papule or subcutaneous nodule. Presentation can be through single or multiple nodules that erode into slow growing ulcerations that easily bleed. The nodules are easily mistaken for lymph nodes, although true lymphadenopathy is rare.

Although GI is generally regarded as an sexually transmitted infections mainly affecting the genital area, the possibility remains that lesions are not always sexually transmitted, but also occur through fecal contamination and autoinoculation.[2,7,9,10]

The differential diagnosis of GI includes primary syphilis; chancroid; condyloma acuminata; leishmaniasis; SCC.

Penile cancer is rare, comprising less than 1% of all male cancer and SCC is the most common variant.[5]

SCC presents as ulcerative, exophytic, papillary or fungating mass with foul smelling discharge. Sometimes phimosis may mask the lesion resulting in delay in seeking medical consultation.[5] Patient may complain of burning or itching over the glans or bleeding from the lesion. Inguinal lymphadenopathy is a common finding in about 60% cases.

In macrophages from patient tissue samples Calymmatobacterium granulomati appears as bipolar-staining intracellular inclusions (Donovan bodies), which give appearance of safety pin due to chromatin condensation at the extremities when stained with Giemsa or Wright stains.[11]

Staining was not done in our case as we did not suspect it as GI because of age of patient, SCC like clinical appearance, chronicity of the lesion and patient's denial of any sexual exposure.

Histopathology of GI shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and the dermis has dense infiltrate of plasma cells and histocytes. In this infiltrate, there are small abscesses comprised of neutrophils. The macrophages have a typical vacuolated appearance.[12] All above mentioned features were seen in our case. Though pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be seen in early stages of SCC of penis, there was no clear cut evidence of malignancy in the form of horn pearls, atypia of individual cells, or mitotic figures.

Available therapeutic options are gentamicin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, azithromycin, and cotrimoxazole.[10] Untreated; GI infection persists and may disseminate or develop abscess formation. SCC may arise from the lesion site. Secondary infectious inoculation may occur, as well as more extensive and deep ulcerations with necrosis, fistula formation, and tissue mutilation. In advanced disease, with vast tissue obliteration and scarring, surgical excision may be required.

In our case, the diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy and patient was successfully treated by giving cotrimoxazole twice a day for 21 days.

In our case, the differential of SCC was overturned by HP examination in favor of GI. Subsequent medical therapy and excision eventually cured the disease and even after 4.5 years of follow-up patient has not developed any recurrence. Once again it proves how efficient a tool histopathology is in dermatologist's armor in diagnosis of uncommon cases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLeod K. Precis of operations performed in the wards of the first surgeon, Medical College Hospital, during the year 1881. Indian Med Gaz. 1882;11:113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier Lmtd; 2008. p. 1271. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan C. Medical cases from Madras general hospital. Indian Med Gaz. 1905;40:411–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balta I, Vahaboglu G, Karabulut AA, Yetisir F, Astarci M, Gungor E, et al. Cutaneous metastases of rectal mucinous adenocarcinoma mimicking granuloma inguinale. Intern Med. 2012;51:2479–81. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guimarães GC, Cunha IW, Soares FA, Lopes A, Torres J, Chaux A, et al. Penile squamous cell carcinoma clinicopathological features, nodal metastasis and outcome in 333 cases. J Urol. 2009;182:528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boye K, Hansen DS. Sequencing of 16S rDNA of Klebsiella: Taxonomic relations within the genus and to other Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Med Microbiol. 2003;292:495–503. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kibbi AG, El-Shareef M. Granuloma inguinale. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Woff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al., editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 1990–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Farrell N. Donovanosis. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:452–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.6.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg J. Studies on granuloma inguinale. V. Isolation of a bacterium resembling Donovania granulomatis from the faeces of a patient with granuloma inguinale. Br J Vener Dis. 1962;38:99–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.38.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganesh R. Donovanosis. In: Sharma VK, editor. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Viva Books Private Limited; 2009. pp. 347–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg J. Studies on granuloma inguinale. IV. Growth requirements of Donovania granulomatis and its relationship to the natural habitat of the organism. Br J Vener Dis. 1959;35:266–8. doi: 10.1136/sti.35.4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas S. Bacterial diseases. In: Elder DE, editor. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 580–1. [Google Scholar]