Abstract

Purpose

To compare macular morphology of pediatric versus adult eyes with epiretinal membrane (ERM) using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT) and identify characteristics associated with postoperative visual acuity (VA).

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed SDOCT from pediatric subjects and a randomly-selected cohort of adult subjects with ERM. Morphologic retinal and ERM features were graded by two masked SDOCT readers and compared with postoperative change in VA.

Results

Pediatric ERMs (ages 0.3-16.5 years) were more confluently attached to the retina than adult ERMs (ages 40-88 years, p=0.009) and had less fibrillary appearance of the inner retina when separation was present (p=0.044). Pediatric ERMs were associated with more vessel dragging (p=0.019) and less external limiting membrane (ELM, p=0.001) and inner segment (IS) band visibility (p=0.010), with a trend towards foveal sparing by ERM (p=0.051) and “taco” retinal folds (p=0.052) compared to adult eyes. VA improvement was associated with intact (p=0.048) and smooth (p=0.055, trend) IS band in children and with smooth IS band (p=0.083, trend) and visible ELM (p=0.098, trend) in adults.

Conclusion

We identified morphologic differences between pediatric and adult ERM on SDOCT. Similar to adults, photoreceptor integrity with pediatric ERM appears to predict better VA changes after surgical ERM removal.

Keywords: Children, Cellophane, Epiretinal membrane, Macular Pucker, Macular Surgery, Membrane Peel, Optical coherence tomography, Pediatric, Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography, Vitrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Epiretinal membrane (ERM) is a layer of cellular proliferation on the inner retinal surface that may cause metamorphopsia, decreased visual acuity (VA), and induction of retinal folds. If visual impairment due to ERM is deemed significant, surgery is often performed to remove the ERM. Previous studies in adult populations have demonstrated that optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging is useful for the perioperative management of ERM removal.1-3 OCT is a viable modality to preoperatively evaluate morphologic features as prognostic factors for postoperative changes in visual acuity after ERM peel as well as identify other configurations at the vitreoretinal interface such as the extent of possible vitreomacular traction, incomplete posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and macular edema.1,4-8 Handheld OCT devices can also be utilized intraoperatively by vitreoretinal surgeons to guide ERM peel, as well as after ERM peel to confirm completeness of the procedure.9,10 In addition, investigations have demonstrated the efficacy of a microscope-mounted OCT device to facilitate hands-free intraoperative imaging.10,11

Little information exists about ERMs in children and how they differ from idiopathic and secondary ERM in adults. Joshi et al pointed to the development of cellular infiltration into the attached posterior hyaloid and associated hyaloid contracture in children with vitreoretinal traction, in contrast to adults in whom proliferation occurs on the inner retinal surface commonly after vitreous separation.12 In children, therefore, the term “contracted premacular proliferation” is also used in light of the common integral interaction with the adherent posterior hyaloid. A limited number of studies have demonstrated statistically significant improvement in VA for pediatric patients with poor preoperative VA who undergo ERM peel, with greater improvements in secondary ERM than idiopathic ERM.13-15 Several case studies have reported preoperative and postoperative OCT images of pediatric ERM peels; however, it remains unknown if the retinal anatomy observed in preoperative OCT images in children may correlate with post-operative changes in visual acuity for children who undergo ERM peel.15,16 Hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT) provides an unmatched ability to visualize retinal layers and the vitreoretinal interface in infants and children.17-19 Subsequently, SDOCT imaging may help provide a better understanding of the differences in macular morphology of children versus adults with ERM. We believe that analysis of OCT images may help provide a better understanding of the differences in macular morphology of children versus adults with ERM as well as possible predictors of visual outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing ERM peel. We hypothesize that photoreceptor integrity will be a prognostic indicator of postoperative visual acuity in children as it is in adults.5,7

METHODS

Data Collection

This retrospective study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided informed consent for imaging as well as analysis of medical records. All OCT images were obtained from an existing research database of adult and pediatric subjects imaged in the Duke University Eye Center operating room with an 840-nm wavelength SDOCT system. All SDOCT images were obtained with the portable handheld SDOCT system (Bioptigen Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC). Subjects with linear scan patterns had their OCTs summed using ImageJ v 1.46 (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland). The volume scan with the best image quality (top priority) and greatest retinal area covered (secondary) was selected for each subject. Funduscopic photographs in children were obtained using the RetCam II Wide-Field Digital Imaging System (Clarity Medical Systems Inc., Pleasanton, CA) and in adults, infrared fundus images were obtained from preoperative Spectralis confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc., Carlsbad, CA).

Eligible subjects were identified by reviewing a medical and surgical records database for diagnoses associated with macular pucker and surgery involving membrane removal. Records were reviewed for two groups: subjects ages 0-17 years old (pediatric group) and subjects 18 years and older (adult group). To be eligible for the pediatric group, subjects were required to have intraoperative SDOCT imaging but ERM removal was not required. To be eligible for the adult group, subjects were required to have intraoperative SDOCT imaging and undergone ERM peel; adult subjects with a macular hole were excluded.

Demographics as well as VAs were recorded from the subjects’ medical records. The best corrected VA available immediately prior to surgery as well as the most recent post-operative best corrected VA were collected from patient charts. As the pediatric visual acuities were often described qualitatively (winces to light, fixes and follows, etc.), the post-operative changes in VAs were classified as either “Better”, “Same”, or “Worse”. When Snellen chart visual acuities were available, an improvement of two or more Snellen lines was classified as “Better,” a VA within one Snellen line of the pre-operative BCVA was classified as “Same,” and a post-operative VA two or more lines worse than the pre-operative BCVA was classified as “Worse”.5 Adult VAs were also classified in this manner to allow for equal comparison between groups.

Image Analysis

Two trained graders masked to age, visual acuity and ocular and systemic health information independently analyzed the images for qualitative OCT variables and quantitative measurements of anatomic features. When the two graders disagreed, a senior masked investigator provided arbitration. The images were evaluated for type of ERM, separation of the ERM from the retinal surface and a characterization of the separation, the presence of ERM on the fovea, partial posterior vitreous detachment, vessel dragging, macular thickness, foveal deformation, retinal folds, external limiting membrane (ELM) visibility and disruption, as well as photoreceptor inner segment (IS, previously known as the inner segment/outer segment junction and also known as the ellipsoid zone) visibility, description and disruption.

The ERMs were classified as either cellophane macular reflex (CMR) or premacular fibrosis (PMF) based on a color fundus photograph, or an infrared en face fundus image if a photograph was not available. An ERM was considered CMR if it was a thin, reflective membrane without macular folds or traction lines on its fundus image while an ERM was classified as PMF if it was a thick, opaque membrane or macular folds or traction lines were noted on its fundus image (Figure 1) .20,21

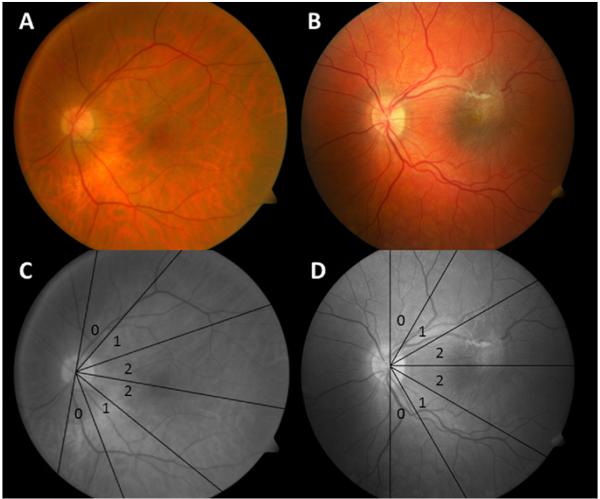

Figure 1. Vessel Traction Score for Cellophane Macular Reflex and Premacular Fibrosis Epiretinal Membranes.

Fundus photographs demonstrate both types of epiretinal membrane (ERM) and vessel traction scoring. Superior and inferior temporal veins are measured at a distance of two optic nerve heads from the center of the optic disc. A displays a 68 year old subject with idiopathic cellophane macular reflex ERM (note the lack of retinal folds). B displays an 11 year old subject with a premacular fibrosis-type ERM (with associated retinal folds) secondary to a combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. C Both temporal veins fall within sector 0 for the adult. D For the child, the superior temporal vein falls within sector 2 and the inferior temporal vein within sector 1.

Vessel dragging was subjectively assessed while the severity of vessel traction was graded independently using the color fundus photograph, infrared en face fundus image, or the summed voxel projection (SVP) from the SDOCT image, based on image availability. A template divided into 30° sectors with the sector between 60° and 90° from the horizontal meridian labeled 0, the sector between 30° and 60° from the horizontal meridian labeled 1, and the sector between 0° and 30° from the horizontal meridian labeled 2 was placed over the fundus image to determine the degree of vessel dragging (Figure 1). The template was centered on the optic nerve with the horizontal median connecting the center of the optic disc to the center of the macula. If the macula was not discernible, the horizontal median was placed halfway between the superior and inferior temporal veins. The sectors that contained the superior and inferior temporal veins at two optic disc lengths from the center of the optic nerve were recorded separately and whichever vessel traction score was higher was the score for that eye.22

The remaining image analysis was based on the SDOCT images.

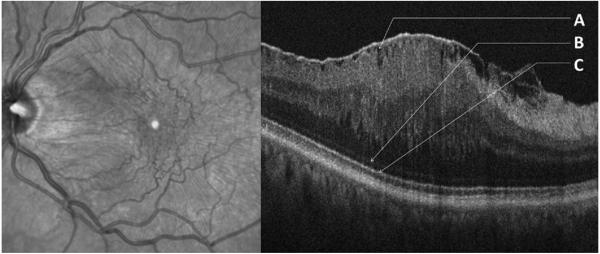

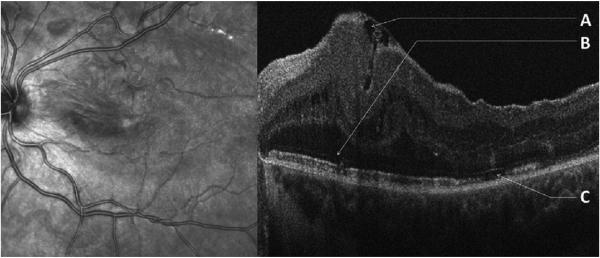

If any hyporeflective, empty space was visible between the ERM and inner retina on either the volume scan or summed linear scan, separation was considered present. Separation at the foveal center was also noted. The surface of the inner retina underneath the lifted ERM was classified as “Fibrillary” if the retinal surface was jagged with hyperreflective signal stretching towards the ERM or “Smooth” if the normal contour is maintained (Figure 2, Figure 3).23 Incidences of ERM sparing the fovea were noted.

Figure 2. Fibrillary Separation of Epiretinal Membrane in an Adult with “Ripple Folds” and Intact, Smooth Outer Bands.

Infrared fundus image (left) and SDOCT image (right) of a 65 year old subject with idiopathic epiretinal membrane (ERM) with “ripple” folds on SDOCT. Traction lines on fundus image classify ERM as premacular fibrosis. A Separation of the ERM from the inner retinal surface with fibrillary changes on the inner retinal contour. B Undisrupted external limiting membrane. C Smooth, undisrupted inner segment band.

Figure 3. Epiretinal Membrane With Minimal Separation and a Smooth Retinal Contour in a Child with a “Taco” Fold and Disrupted Outer Bands.

Infrared fundus image (left) and SDOCT image (right) of a 16 year old subject with an epiretinal membrane (ERM) with “taco” fold secondary to previous retinal detachment. Retinal folds on fundus image classify ERM as premacular fibrosis. A Separation of the ERM from the inner retinal surface with no fibrillary changes on the inner retinal contour with an underlying single, deep “taco” fold. B Disrupted external limiting membrane. C Disrupted inner segment band with ragged inner segment band to the left.

Complete PVD could not be confirmed on most SDOCT scans; therefore, partial PVD was noted and then classified based on whether vitreous attachment was visible at the fovea, optic nerve, or both locations. Foveal deformation was defined as loss of the foveal pit. Retinal folds were characterized as “ripple” folds, defined as mild undulations of the inner surface (Figure 2), and “taco” folds, defined as large undulations with apposition of the inner retinal layers with possible invagination into the outer layers (Figure 3).24 ELM and IS bands were each characterized as visible if graders could identify them on either the SDOCT volume or summed linear scan. IS bands were described as either “smooth” or “ragged” with IS band disruption noted; ELM disruption was identified as well (Figure 2, Figure 3).

The macular thickness was measured using the caliper feature of InVivoVueClinic v 1.3.4 software (Bioptigen Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) from Bruch’s membrane to the inner limiting membrane at the best estimated site of the foveal center. The mean macular thickness measurement from the two graders was recorded if the two measurements were within 50 μm and adjudicated if the difference was greater than 50 μm.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using JMP Pro software v 10.0 (SAS, Cary, NC). Two-tailed Fisher exact tests were performed to determine if the incidence of the various morphologic parameters differed in the pediatric and adult groups as well as if there was a correlation between any of the parameters and the changes in postoperative visual acuity in the pediatric and adult groups as well as all subjects combined. A multivariable ordinal logistic model could not be fit due to sample size. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was run to determine if there was a difference in macular thickness between the two groups or if there was a correlation between macular thickness and postoperative changes in visual acuities.

RESULTS

Demographics

Forty-two pediatric eyes were identified in the existing imaging database with ERM; however, 10 eyes were not imaged until after ERM peel while 6 eyes had imaging sessions that were not gradable due to image quality, including one subject with bilateral ERM. One eye per patient in a total of 26 children and 26 adults were included in this analysis (Table 1). Gender and race distributions did not differ significantly between the two groups. The pediatric subject ages ranged from 0.3 to 16.5 years with a mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 6.1 ± 5.3 years. The adult subject ages ranged from 40 to 88 years with a mean age ± SD of 69.9 ± 10.0 years. Mean ± SD for duration of follow-up to determine VA after ERM removal was 9.7 ± 10.7 months (range of 1 to 39 months) for pediatric subjects and 7.0 ± 7.4 months (range of 1 to 35 months) for adult subjects. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean follow-up time for final VA between the pediatric and adult groups (p=0.942).

Table 1. Demographics of Study Subjects.

| Pediatric | Adult | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. Subjects | 26 | 26 | |

|

| |||

| Gender No. (%) | 0.165 | ||

| Female | 10 (38) | 16(62) | |

|

| |||

| Race No. (%) | 0.465 | ||

| Caucasian | 17 (65) | 21 (81) | |

| African-American | 6 (23) | 4 (15) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | |

|

| |||

| Age (Years) | <0.001 | ||

| Range | 0.3-16.5 | 40.0-88.0 | |

| Median | 4.8 | 70.5 | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (5.3) | 69.9 (10.0) | |

|

| |||

| Eye No. (%) | 0.089 | ||

| OD | 14 (54) | 7 (27) | |

|

| |||

| Etiology (%) | <0.001 | ||

| ROP | 7 (27) | 0 | |

| Retinal Detachment | 4 (15) | 7 (27) | |

| Retinoschisis | 3 (12) | 0 | |

| Congenital Defect* | 3 (12) | 0 | |

| Trauma | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | |

| FEVR | 2 (8) | 0 | |

| Combined Hamartoma | 2 (8) | 0 | |

| Idiopathic | 1 (4) | 14 (54) | |

| Toxocariasis | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Hemorrhage† | 0 | 2 (8) | |

|

| |||

| Preoperative Lens Status (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Phakic | 22 (84) | 13 (50) | |

| Pseudophakic | 2 (8) | 13 (50) | |

| Aphakic | 2 (8) | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Previous Vitrectomy (%) | 9 (35) | 3 (12) | 0.098 |

SD, standard deviation; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity

Congenital defects present in children were persistent fetal vasculature, retinitis pigmentosa, and ring chromosome 22 syndrome.

Hemorrhage in the adult group were associated with sickle cell retinopathy and a macro-arteriolar aneurysm.

The two groups had different etiologies of ERM as 54% of the adult group had idiopathic ERM while 96% of the pediatric ERMs were associated with other pathology (Table 1). All 26 adult eyes underwent surgical treatment of ERM. Four of the 26 pediatric eyes that had the examination under anesthesia did not have ERM removal after assessment of retinal disease and comorbidities, age, visual significance, and prognosis for visual improvement. The remaining 22 pediatric subjects underwent surgical treatment in a manner similar to adult subjects.

At baseline, the pediatric group had 22 phakic, 2 pseudophakic, and 2 aphakic subjects, and 9 (35%) of the pediatric eyes had previous vitrectomy surgery including anterior vitrectomy performed with the cataract surgeries. At the time of postoperative VA measurement for the 22 pediatric subjects who underwent ERM removal, there were 16 phakic, 3 pseudophakic, and 3 aphakic subjects. In addition, three phakic subjects developed new cataracts. In the adult cohort, there were 13 phakic and 13 pseudophakic subjects at baseline and three adult eyes that had prior vitrectomy. There were 10 cataracts noted on preoperative exam. At the time of final VA measurement, one subject had his or her cataract removed, resulting in 14 pseudophakic and 12 phakic subjects. No cataract progression was observed in the remaining 12 phakic adults during their follow-up; therefore, the two groups had no significant difference in visually significant cataract at the time of final VA measurement.

Graded Macular Morphology of Participating Subjects

The incidences of all morphologic features analyzed with SDOCT in both the pediatric and adult groups are listed in Table 2. The greatest difference noted between the groups was children were significantly less likely to have any ERM separation from the macula (p=0.009) or ERM separation specifically at the fovea (p=0.009) compared to the adult group. If there was ERM separation from the retina, the inner retinal contour of pediatric subjects was more likely to remain smooth rather than develop a fibrillary appearance compared to the adult group (p=0.044). Children were more likely to have subjectively graded vessel dragging (p=0.019) and 5 of 23 children (22%) had a vessel traction score of 2 while no adults had this severe vessel dragging (p=0.111). The ELM (p=0.010) and IS band (p=0.010) were also significantly more visible in the adult group compared to the pediatric group.

Table 2. Incidences of Morphologic Features in Children and Adults with Epiretinal Membranes.

| Pediatric Incidence | Adult Incidence | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=26 | N=26 | ||

| Present/Total (%) | Present/Total (%) | ||

| ERM Type | 0.657 | ||

| Cellophane Macular Reflex | 4/20 (20) | 3/10 (30) | |

| Premacular Fibrosis | 16/20 (80) | 7/10 (70) | |

| Any ERM Separation From Retina | 15/26 (58) | 24/26 (92) | 0.009* |

| ERM Separation at Fovea | 2/22 (9) | 12/26 (46) | 0.009* |

| Appearance of Separation | 0.044* | ||

| Fibrillary | 6/15 (40) | 18/24 (75) | |

| Smooth | 9/15 (60) | 6/24 (25) | |

| Fovea Spared by ERM | 5/26 (19) | 0/26 (0) | 0.051 |

|

| |||

| Partial PVD† | 8/14 (57) | 6/23 (26) | 0.085 |

| Vitreous Attachment | 1.000 | ||

| Optic Nerve | 1/8 (12) | 1/6 (17) | |

| Fovea | 1/8 (12) | 0/6 (0) | |

| Both | 6/8 (75) | 5/6 (83) | |

|

| |||

| Vessel Dragging | 15/23 (65) | 7/25 (28) | 0.019* |

| Vessel Traction Score | 0.111 | ||

| 0 | 4/23 (17) | 5/19 (26) | |

| 1 | 14/23 (61) | 14/19 (74) | |

| 2 | 5/23 (22) | 0/19 (0) | |

|

| |||

| Foveal Deformation | 18/20 (90) | 26/26 (100) | 0.184 |

| Taco Folds | 10/26 (38) | 3/26 (12) | 0.052 |

| Ripple Folds | 21/26 (81) | 25/26 (96) | 0.191 |

|

| |||

| ELM Visible | 9/25 (36) | 19/25 (76) | 0.001* |

| ELM Disruption | 5/8 (63) | 3/15 (20) | 0.071 |

| IS Band Visible | 19/26 (73) | 26/26 (100) | 0.010* |

| IS Band Description | 1.000 | ||

| Smooth | 15/18 (83) | 20/25 (80) | |

| Ragged | 3/18 (17) | 5/25 (20) | |

| IS Band Disruption | 3/12 (25) | 8/20 (40) | 0.465 |

ERM, epiretinal membrane; PVD, posterior vitreous detachment; ELM, external limiting membrane; IS, inner segment.

Indicates statistical significance

Excludes subjects who underwent previous vitrectomy (17 pediatric subjects and 23 adult subjects)

While not statistically significant, several other trends were observed in the two groups (Table 2). The ERM involved the fovea in every adult subject but the ERM spared the fovea in 5 of 26 children (p=0.051). Ten of 26 children had “taco” retinal folds but only 3 of the 26 adults had this type of fold (p=0.052). “Ripple” retina folds were common in both groups and thus both groups’ ERMs were predominantly described as PMF versus CMR. While the ELM was less visible in the pediatric group, when it was observed, it was more likely to be disrupted than in the adult group (p=0.071). Of the 14 pediatric subjects and 23 adult subjects with no prior vitrectomy and adequate SDOCT imaging for grading of partial PVD, 8 (57%) and 6 (26%), respectively, had partial PVD on SDOCT images with both groups demonstrating vitreous attachment predominantly at both the optic nerve and fovea. However, from eye examination and surgical records, the remaining 6 (43%) pediatric eyes had attached posterior vitreous while 11 (48%) adult eyes had a complete PVD. Thus, only 26% of the adult eyes had any attached posterior vitreous whereas all of the pediatric eyes had some or all of the posterior vitreous attached. Mean macular thickness ± SD was 547 ± 245 μm in children and 481 ± 166 μm in adults (p=0.421). Macular thickness was measurable in 21 of 26 children and 25 of 26 adults. One adult macula could not be measured as the lower limit of the retina was not captured on the screen. Five pediatric macular thicknesses were not measurable as one subject had a complete detachment of the macula, two did not contain the lower limit of the macula on the screen, and two images did not contain a recognizable macula.

On examining the OCT images and fundus examination of pediatric and adult eyes with ERM that had prior vitrectomy, there were no unique features that were identified in the small number of post-vitrectomy membranes. An comparison of macular morphology between the 17 pediatric and 23 adult eyes with no previous vitreous surgery did not change current analysis other than the difference between pediatric and adult features went from significant (Table 2) to a trend for the following: any ERM separation (pediatric 11 (64.7%), adult 21 (91.3%), p=0.053), “Fibrillary” versus “Smooth” retinal interface (pediatric 7/11, adult 5/21, p=0.053), and IS band visible (pediatric 14/17, adult 23/23, p=0.069).

Postoperative Changes in Visual Acuity

The morphologic parameters analyzed with SDOCT associated with better functional outcomes after surgical ERM removal are displayed in Table 3. Preoperative and postoperative VA data were available for 20 pediatric subjects and 21 adult subjects; preoperative and postoperative Snellen chart VAs were available for 10 pediatric subjects and 16 adult subjects. Overall, the pediatric and adult groups had nearly identical distributions of postoperative visual acuity outcomes. The pediatric group had a significantly better functional outcome if the preoperative SDOCT demonstrated an undisrupted IS band (p=0.048) while the adult group did not (p=1.000). There was also a trend towards improved postoperative VA in the pediatric group if the IS band on preoperative SDOCT was smooth as opposed to ragged (p=0.055) and this same relationship existed as a trend in the adult group (p=0.083). Exclusion of pediatric subjects who had undergone prior vitrectomy did not significantly change these findings. In adults there was a trend towards better postoperative functional outcomes if the ELM was visible (p=0.098) whereas in children there was no trend (p=0.538). Of note, exclusion of the three adult subjects who had undergone prior vitrectomy, all of whom had postoperative improvements in VA, strengthened the trend of ELM visibility (p=0.040) while weakening the trend of “Smooth” IS band (0.161) with postoperative improvements in VA. When the pediatric and adult groups were combined and all 41 subjects were analyzed in aggregate, a preoperative SDOCT demonstrating a smooth IS band was significantly correlated to better postoperative changes in VA (p=0.008). Analysis of the combined cohorts excluding subjects with prior vitrectomy exhibited the same changes as noted for the adult cohort.

Table 3. Photoreceptor Morphologic Parameters Versus Visual Acuity Changes after Epiretinal Membrane Peel in Pediatric and Adult Subjects.

| Pre-Operative SDOCT Finding | Subject Group (No. Eyes/Total) |

Changes in Visual Acuity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better | Same | Worse | P-value | |||

| Pediatric (N=20) | 9 | 9 | 2 | |||

| Adult (N=26) | 11 | 12 | 3 | |||

| IS Band Disruption | Pediatric | Y | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.048 |

| Within 500 μm of the Fovea | 9/20 | N | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

|

|

||||||

| Adult | Y | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1.000 | |

| 20/26 | N | 4 | 6 | 2 | ||

|

|

||||||

| All Subjects | Y | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0.430 | |

| 29/46 | N | 9 | 7 | 2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IS Band Description | Pediatric | Smooth | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0.055 |

| 14/20 | Ragged | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Adult | Smooth | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0.083 | |

| 25/26 | Ragged | 0 | 4 | 1 | ||

|

|

||||||

| All Subjects | Smooth | 18 | 11 | 2 | 0.008 | |

| 39/46 | Ragged | 0 | 7 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||||

| ELM Band Visible | Pediatric | Y | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0.538 |

| 20/20 | N | 4 | 6 | 2 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Adult | Y | 10 | 6 | 3 | 0.098 | |

| 25/26 | N | 1 | 5 | 0 | ||

|

|

||||||

| All Subjects | Y | 15 | 9 | 3 | 0.170 | |

| 45/46 | N | 5 | 11 | 2 | ||

SDOCT, spectral domain optical coherence tomography; IS, inner segment; ELM, external limiting membrane.

DISCUSSION

SDOCT allows us to better identify and characterize the differences in macular morphology of children versus adults with ERM and use these structural findings identified by SDOCT as prognostic indicators of functional outcomes after surgical removal of ERM. This study found that children have an increased incidence of ERM confluent attachment to the retina and fovea, vessel dragging, foveal sparing by the ERM, and “taco” retinal folds as well as less fibrillary changes on the inner retina compared to adults. In addition, a smooth, undisrupted IS band on preoperative SDOCT imaging was associated with a better post-operative change in visual acuity for children who underwent ERM removal.

While ERMs in adults have been widely described and studied, little information exists regarding ERMs in children. In 1975, Wise25 theorized the “opaque gray fibrosis” he observed in two patients aged 35 and 36 occurred as a result of a defect during embryonic development. He believed this form of ERM differed from the idiopathic form acquired later in life by “its congenital onset, absence of the characteristic retinal glint, and deep retinal edema”.25 The first victrectomy with epiretinal membrane peel for a young patient with ERM was reported by Michels26 in 1984 on a 9 year old patient. It is now accepted that there is a much lower incidence of ERM in children than in adults as pediatric ERMs typically develop secondary to another pathology such as trauma or inflammation rather than the idiopathic form associated with PVD common in adults.27 The opaque PMF form of ERM is more prevalent in children while the translucent CMR ERM is observed more frequently in adults.20,21,27 Ultrastructural studies via electron microscopy demonstrate increased myofibroblast and collagen with a lower incidence of retinal pigment epithelial cells in membranes obtained from children compared to adults. This difference in histological features may explain the increased frequency of thicker, opaque fibrosis in children.28 Clinical evaluation also suggests a higher incidence of ERM adherence to vessels, and infiltration into the posterior vitreous with traction and subsequent vessel distortion in the pediatric population.12,14

The epidemiology of the ERMs in this study differs from previous reports. More than half the adult subjects had an idiopathic ERM while only one pediatric subject had an idiopathic ERM. The incidence of pediatric ERM with a secondary etiology was much greater in this study with a different distribution than previously published reports (Table 4, note that “All Subjects” lists the etiologies of all children with epiretinal membranes who were identified in the existing subject database while “Study Subjects” lists the etiologies of only the subjects with graded OCT images who were included for the current analysis.). This may be due to the tertiary nature of the participating institution and our selection criteria for inclusion in the study. All subjects imaged were referred from an outside facility and idiopathic ERMs in young children that did not cause significant visual impairment may not have been sent to the participating physician or examined under anesthesia. This may also explain the high rate of ERMs developing secondary to another etiology in adults as well.

Table 4. A Comparison of Etiologies of Epiretinal Membrane in Children in Published Studies With More Than One Etiology*.

| Rothman 2013 | Ferrone 201115 | Khaja 200827 | Benhamou 200214 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects | OCT Study Subjects | ||||

| N=42 | N=26 | N=14 | N=44 | N=20 | |

| Age | |||||

| Range (Years) | 0.1-18.0 | 0.3-16.5 | 0.5-11.0 | 0.3-18.0 | 7-26.0 |

| Mean (Years) | 5.S | 6.1 | 8.0 | 12.4 | 16.6 |

| Etiology | |||||

| ROP (%) | 13 (31) | 7 (27) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retinal Detachment (%) | 6 (14) | 4 (15) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Retinoschisis (%) | 5 (12) | 3 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Congenital Defect (%) | 5 (12) | 3 (12) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Trauma (%) | 4 (10) | 3 (12) | 1 (7) | 17 (39) | 0 |

| FEVR (%) | 4 (10) | 2 (8) | 5 (35) | 0 | 0 |

| Combined Hamartoma (%) | 3 (7) | 2 (8) | 4 (29) | 2 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Toxocariasis (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (5) |

| Toxoplasmosis (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3(15) |

| Idiopathic (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 4 (29) | 12 (27) | 13 (65) |

| Uveitis (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (21) | 2 (10) |

| Unspecified (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| ERM Type | |||||

| CMR (%) | ----- | 4/20 (20) | N/A | 7/28 (25) | 7/20 (35) |

| PMF (%) | ----- | 16/20 (80) | N/A | 21/28 (75) | 13/20 (65) |

| PVD | ----- | 9/23 (39)† | 0 | N/A | 13/20 (35) |

OCT, optical coherence tomography; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; FEVR, familiar exudative vitreoretinopathy; CMR, cellophane macular reflex; PMF, premacular fibrosis; PVD, posterior vitreous detachment;

Previous studies that only included one etiology for pediatric epiretinal membranes were excluded from Table 4.13,28

Based on intraoperative findings.

The classification of ERM in the current study as CMR or PMF agreed with previous findings in the pediatric population but not the adult population. Eighty percent of pediatric ERMs were classified as PMF which is consistent with previous findings (Table 4). Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a lower rate of PMF in adults ranging between 28% and 44% but the rate of PMF type ERM in adults in this study was 70%.20,21,29 The high rate of PMF in adults may be explained by the unusually high rate of non-idiopathic adult ERM in his study; the secondary etiology of ERM may cause greater activation of myofibroblasts which synthesize collagen types I and II, which are associated with PMF, as part of the healing response to the primary insult.30 Most adult cases were classified as PMF primarily due to the high incidence of retinal folds on the infrared fundus image, which has been reported to detect more folds than are observed clinically.31 The finding of folds was later supported by the nearly unanimous presence of “ripple” retinal folds on the adult SDOCT scans. These cases may not have been referred to the participating institution until the ERM was severe enough to be classified as PMF. Last, only ten adult ERMs had adequate accessible preoperative en face imaging and could be classified by fundus image.

SDOCT provided a useful modality to compare the vitreoretinal interface in children and adults with ERM. On SDOCT images, there was a greater incidence of confluent attachment both globally across the retina and focally at the fovea for pediatrics ERMs than adult ERMs. Multiple studies describe pediatric ERM as strongly adherent based on clinical descriptions.28,32 Kim et al22 found that the extent of ERM adherence to the retina correlates with surgical difficulty in adults; thus, increased adherence in children may cause ERM removal in children to be technically difficult. In the pediatric cases in the current study, however, the surgeon did not find any additional difficulty in removing the pediatric membranes from the macula when compared to the adult eyes. Kim et al22 also postulate that the fibrillary change often seen along the retinal surface when the ERM is separated from the retina is likely due to glial cells.23 As Smiddy27 found a relative increase in RPE cells in adult ERMs versus pediatric ERMs, perhaps this hyperreflective stranding may be due to the adherent nature of RPE cells, which rely on various adhesion molecules to form the blood-retinal barrier.33

Previous reports of PVD in the pediatric population range from none of Ferrone and Chaudhary’s14 subjects to all 11 pediatric subjects described by Smiddy et al27 (Table 4). The difference in incidence in prior studies may have been affected in part by the inability to precisely assess the vitreoretinal interface with the more recently available OCT imaging. Smiddy may also have had PVD in every subject because he only included idiopathic ERM while only 29% of Ferrone and Chaudhary’s cases were idiopathic ERMs. The current study found no complete PVD in pediatric eyes but an incidence of 57% partial PVDs in those subjects with no prior vitrectomy, which is somewhat consistent with the rate of 35% found by Benhamou et al13. The wide range in PVD incidences may be explained by the equally diverse causes of ERM in various studies. It should be noted that age did not play a role in incidence of PVD in the pediatric group in the current study (p=0.958), and when a partial PVD did occur in the pediatric group, the site of vitreous separation followed the classic pattern described in adults with vitreous adherence remaining mostly at both the optic nerve and fovea.34 Our findings with the assistance of SDOCT examination, support the conventional evidence that complete posterior vitreous separation is uncommon in pediatric ERM (not seen in the pediatric cohort) and common in the adult eyes with ERM (48% with complete PVD, 26% with partial PVD).

Subjective vessel dragging was identified more frequently in children than adults and the vessel traction score also distinguished five pediatric cases of severe vessel dragging that fell into sector 2 compared to zero cases in the adult population. The etiologies of these ERMs were two children with ROP, one child with FEVR, one child with a combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE, and one child with a history of Toxocariasis. Benhamou et al13 describe strong adherence of pediatric ERM to the temporal retinal vessels in multiple cases, which may increase the traction pulling the arcades temporally.14 However, it is notable that only children exhibited vessel dragging into the more severe sector 2. There may not have been a statistically significant difference in the highest vessel template score achieved between children and adults because sample sizes in both groups were too small and because normal temporal retinal veins may fall within sector 1 without dragging.

Other notable analyses from this study involve retinal folds, foveal sparing by ERM, and macular thickness. While “ripple” retinal folds were seen in nearly all eyes with ERM, a “taco” retinal fold, where the traction is severe enough to cause the inner retinal layers to invaginate into the outer layers, was seen more frequently in children versus adults. Previous literature reports that both of these folds are elastic and may resolve with observation; in the setting of an ERM peel, these folds do not appear to influence postoperative changes in visual acuity.32 Although there was a trend towards foveal sparing by ERM in children, it should be noted that some pediatric subjects had other pathologies that may have been the initial indication for surgery. Huang et al35 found that eccentric ERMs display preserved foveal function as measured by multifocal electroretinography and surgical removal of ERM should not affect vision.

Previous studies in adults have demonstrated that photoreceptor integrity of the outer bands identified on preoperative SDOCT is the most useful prognostic indicator of postoperative changes in visual acuity after ERM peel. For example, Suh et al5 found a statistically significant correlation between disruption of the inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction and poor visual outcome, regardless of whether this disruption developed preoperatively, intraoperatively, or postoperatively in their prospective, randomized controlled trial. Other predictors of post-operative functional improvements include cone outer segment tip line disruption and photoreceptor outer segment length.7,8 It is believed that the tractional force from the ERM may cause irreversible damage to the rods and cones that can be diagnosed preoperatively on SDOCT.

The current study supports these previous findings and suggests that photoreceptor integrity is also important in the pediatric population. In children, intact photoreceptor integrity was best identified by an undisrupted IS band described as smooth versus ragged. In adults, a smooth IS band and ELM visibility were the best representations of photoreceptor integrity and correlated with better functional outcomes after ERM surgical removal. When both groups were combined, the description of the preoperative IS band as smooth became even more strongly correlated with a postoperative beneficial change in visual acuity, while ELM visibility still had a notable trend of better postoperative functional outcomes. Thus, assessment of photoreceptor integrity in children with ERM on preoperative SDOCT can provide additional information as a prognostic tool when deciding whether to surgically remove the ERM in children.

Many of the limitations of this study are due to its retrospective design and to the fact that preoperative assessment of pediatric and adult cases is quite different due to the difference in age and limited potential cooperation of many pediatric patients. Our sample size was limited by the rare incidence of pediatric ERM evaluated by vitreoretinal specialists. For example, Ferrone et al. conducted a 12-year retrospective review and only included 14 pediatric patients that had ERM surgery. In order to include the full spectrum of pediatric ERM examined under anesthesia in this series, 4 pediatric patients were included who did not undergo ERM peel while all of the adults proceeded to membrane removal. The severity of the pathology in these 4 pediatric cases was comparable to the 22 children who underwent ERM peel, although their potential for vision recovery was likely more limited, and their etiologies included two retinal detachment cases, one juvenile X-linked retinoschisis, and one persistent fetal vasculature. The retrospective nature of this analysis also resulted in no standardized method of documenting VA in children as medical records from different pediatric ophthalmologists had to be interpreted. There was also no standardized follow-up time for recording postoperative VA, which ranged from 1 to 39 months. However, there was no statistical difference in mean follow-up at the time of VA measurement in the adult and pediatric groups.

The image quality for some pediatric subjects was suboptimal which may explain the increased incidence of visible ELM and IS band in adults. Acquiring high quality SDOCT images in infants and young children is difficult because the optics used are based on assumptions about the dynamic axial length, refractive error, corneal curvature, and astigmatism of this age group.18 Because of the image quality, the graders were conservative and not all morphologic parameters could be evaluated in all subjects. The image quality also led to a qualitative evaluation of the photoreceptor layers by noting layer visibility, description, and disruption, rather than more quantitative methods such as measuring the photoreceptor outer segment length.8 There were 18 linear scans available for adults and only 13 linear scans available for pediatric subjects; in addition, en face imaging analysis to determine if an ERM was CMR versus PMF relied primarily on infrared imaging in adults but primarily RetCam imaging in the pediatric group.

Finally, each subject group had ERMs with many different etiologies. While the etiology of the ERM was not consistent between the adult and pediatric groups, the current pediatric subject group reflects the wide range of presentations for pediatric ERMs; limiting the study to idiopathic pediatric ERMs would not accurately portray ERMs in children and severely limit the study size. As this is the first study to demonstrate a correlation between preoperative SDOCT morphology and postoperative changes in VA for pediatric subjects who undergo ERM peel, and the numbers of patients was small, further work is warranted to incorporate these findings into clinical practice. A prospective study of pediatric subjects with ERM would likely be useful.

In summary, we have found that SDOCT allows for more accurate evaluation of the vitreoretinal interface and macula in children with ERM and, as in adults, provides useful preoperative information. Pediatric ERMs tend to be more confluently attached to the retina than adult ERMs with less fibrillary appearance of the inner retinal contour when separation is present; pediatric ERMs may also cause more severe vessel dragging, foveal sparing by ERM, “taco” retinal folds and less ELM and IS band visibility. Based on our findings, we suggest that preoperative SDOCT imaging of the macula in children with ERM is useful to determine location of folds and if the IS band is smooth and intact. This information could be incorporated into surgical planning, recognizing that there are many social and anatomic factors to consider before performing pediatric vitreoretinal surgery including unique aspects of amblyopia and complex pathology other than the ERM.

Summary Statement.

On spectral domain optical coherence tomography, we defined differences in macular morphology between pediatric and adult subjects with epiretinal membranes and found that preoperative photoreceptor integrity was a prognostic indicator of visual acuity improvement after victrectomy in both groups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Du Tran-Viet and Neeru Sarin for complex imaging and research assistance, Dr. Sandra Stinnett for assistance with statistics, and Dr. Grace Prakalapakorn for guidance regarding the analysis of VA changes in children.

Funding: This study was funded in part by The Hartwell Foundation, The Andrew Family Foundation, Research to Prevent Blindness, the National Center for Research Resources Grant 1UL1RR024128-01 and the National Eye Institute Grant 1R01EY023039-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Toth receives royalties through her university from Alcon and research support from Bioptigen, Genentech, and Physical Sciences Inc. She also has patents pending in OCT imaging and analysis. No other authors have financial disclosures. No authors have a propriety interest in the current study.

Meeting Presentation: This study was presented in part at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, Seattle, WA, May 7, 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.Do DV, Cho M, Nguyen QD, et al. Impact of optical coherence tomography on surgical decision making for epiretinal membranes and vitreomacular traction. Retina. 2007;27:552–556. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31802c518b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano Y, Yasukawa T, Ogura Y. Optical coherence tomography guided peeling of macular epiretinal membrane. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;5:27–29. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH, Kim YM, Chung EJ, et al. Structural and functional predictors of visual outcome of epiretinal membrane surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koizumi H, Spaide RF, Fisher YL, et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of vitreomacular traction and epiretinal membrane using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh MH, Seo JM, Park KH, Yu HG. Associations between macular findings by optical coherence tomography and visual outcomes after epiretinal membrane removal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ophir A, Martinez MR. Epiretinal membranes and incomplete posterior vitreous detachment in diabetic macular edema, detected by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:6414–6420. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimozono M, Oishi A, Hata M, et al. The significance of cone outer segment tips as a prognostic factor in epiretinal membrane surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiono A, Kogo J, Klose G, et al. Photoreceptor outer segment length: a prognostic factor for idiopathic epiretinal membrane surgery. Ophthalmol. 2013;120:788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayani PN, Maldonado R, Farsiu S, Toth CA. Intraoperative use of handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging in macular surgery. Retina. 2009;29:1457–1468. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181b266bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray R, Baranano DE, Fortun JA, et al. Intraoperative microscope-mounted spectral domain optical coherence tomography for evaluation of retinal anatomy during macular surgery. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2212–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehlers JP, Tao YK, Farsiu S, et al. Integration of a spectral domain optical coherence tomography system into a surgical microscope for intraoperative imaging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3153–3159. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi MM, Ciaccia S, Trese MT, Capone A., Jr. Posterior hyaloid contracture in pediatric vitreoretinopathies. Retina. 2006;26:38–41. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000244287.63757.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banach MJ, Hassan TS, Cox MS, et al. Clinical course and surgical treatment of macular epiretinal membranes in young subjects. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benhamou N, Massin P, Spolaore R, et al. Surgical management of epiretinal membrane in young patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:358–364. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrone PJ, Chaudhary KM. Macular epiretinal membrane peeling treatment outcomes in young children. Retina. 2012;32:530–536. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0B013E318233AD26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott AW, Farsiu S, Enyedi LB, et al. Imaging the infant retina with a hand-held spectral-domain optical coherence tomography device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavala SH, Farsiu S, Maldonado R, et al. Insights into advanced retinopathy of prematurity using handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2448–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2678–2685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee AC, Maldonado RS, Sarin N, et al. Macular features from spectral-domain optical coherence tomography as an adjunct to indirect ophthalmoscopy in retinopathy of prematurity. Retina. 2011;31:1470–1482. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821dfa6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, et al. Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes. The Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser-Bell S, Ying-Lai M, Klein R, Varma R. Prevalence and associations of epiretinal membranes in latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1732–1736. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watzke RC, Robertson JE, Jr., Palmer EA, et al. Photographic grading in the retinopathy of prematurity cryotherapy trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:950–955. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070090052038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Chhablani J, Chan CK, et al. Retinal adherence and fibrillary surface changes correlate with surgical difficulty of epiretinal membrane removal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong R. Longitudinal study of macular folds by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wise GN. Congenital preretinal macular fibrosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:363–365. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michels RG. Vitrectomy for macular pucker. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1384–1388. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khaja HA, McCannel CA, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Incidence and clinical characteristics of epiretinal membranes in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:632–636. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smiddy WE, Michels RG, Gilbert HD, Green WR. Clinicopathologic study of idiopathic macular pucker in children and young adults. Retina. 1992;12:232–236. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aung KZ, Makeyeva G, Adams MK, et al. THE PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS OF EPIRETINAL MEMBRANES: The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Retina. 2013;33:1026–1034. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182733f25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kritzenberger M, Junglas B, Framme C, et al. Different collagen types define two types of idiopathic epiretinal membranes. Histopathology. 2011;58:953–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remky A, Beausencourt E, Hartnett ME, et al. Infrared imaging of cystoid macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1999;237:897–901. doi: 10.1007/s004170050383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang X, Chen Z, Weng Y, et al. Surgical outcome after removal of idiopathic macular epiretinal membrane in young patients. Eye. 2008;22:1430–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thumann G, Hoffan S, Hinton DR. Cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Hinton DR. Retina. Elsevier, Inc.; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. pp. 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchino E, Uemura A, Ohba N. Initial stages of posterior vitreous detachment in healthy eyes of older persons evaluated by optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1475–1479. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang JU, Sohn J, Moon BG, et al. Assessment of macular function for idiopathic epiretinal membranes classified by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3562–3569. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]