Abstract

Alopecia is a persistent problem in captive macaque populations and despite recent interest, no factors have been identified that can unequivocally explain the presence of alopecia in a majority of cases. Seasonal, demographic and environmental factors have been identified as affecting alopecia presentation in rhesus macaques, the most widely studied macaque species. However, few studies have investigated alopecia rates in other macaque species. We report alopecia scores over a period of 12 months for three macaque species (Macaca nemestrina, M. mulatta, and M. fascicularis) housed at three indoor facilities within the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC) in Seattle. Clear species differences emerged with cynomolgus (M. fascicularis) showing the lowest alopecia rates and pigtails (M. nemestrina) the highest rates. Further analysis of pigtail and rhesus (M. mulatta) macaques revealed that sex effects were apparent for rhesus but not pigtails. Age and seasonal effects were evident for both species. In contrast to previous reports, we found that older animals (over 10 years of age) had improved alopecia scores in comparison to younger adults. This is the first report on alopecia rates in pigtail macaques and the first comparison of alopecia scores in pigtail, cynomolgus, and rhesus macaques housed under similar conditions.

Keywords: alopecia, pigtail macaques, rhesus macaques, cynomolgus macaques, age differences

Introduction

Although alopecia is rarely reported in wild populations of non-human primates, it has been a persistent concern in captive populations. The problem has received attention from regulatory agencies in recent years since it appears, at least subjectively, to be related to an animal's health and well being. Several studies report prevalence rates in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), either for individually-housed animals or for captive social groups. Rates vary widely (between 20 and 86%) and generally appear lower in colonies that have access to the outdoors and a more naturalistic substrate allowing increased opportunity for foraging [Beisner & Isbell, 2008; Kramer et al., 2010; Lutz et al., 2013; Steinmetz et al., 2006]. Several other factors have been implicated in increasing the risk of alopecia in rhesus macaques, including being female [Kramer et al., 2010], greater age [Kramer et al., 2010; Steinmetz et al., 2006], pregnancy [Beisner & Isbell, 2009] and living in crowded environments [Steinmetz et al., 2006].

Hair pulling is another factor which has been implicated in increased levels of alopecia in rhesus macaques. A large study comparing alopecia rates for rhesus macaques housed at four national primate research centers documented a significant relationship between animals that pulled hair and animals with alopecia [Lutz et al., 2013]. However, despite this strong relationship, hair pulling explained only 4 to 7 percent of the variance in alopecia presentation in the study. Thus, not all animals with alopecia engage in hair pulling and not all animals that pull hair have alopecia. Steinmetz and colleagues [2005] also concluded hair pulling was unlikely to be responsible for most alopecia observed in rhesus macaques, partly based on negative histologic findings that would indicate hair pulling. Despite its inability to explain the majority of alopecia cases, Kramer and others [2011] have more recently argued that hair pulling may explain most of a specific subset of alopecia cases.

Differences in social housing situations (e.g., single vs. pair or group housed) might also affect alopecia ratings. Direct, comparative data regarding the effects of single vs. social housing on alopecia in laboratory animals is currently lacking. To date, most studies report on animals that are either exclusively socially housed [Beisner & Isbell, 2008; Steinmetz, et al., 2006] or exclusively singly-housed [Kramer et al., 2010; Lutz et al., 2013]. Possible benefits of social housing, including potentially reducing alopecia, are likely to receive added attention in the near future as laboratories implement new guidelines for social housing of animals. Despite the lack of direct evidence at this point, an effect of social housing on alopecia, moderated by stress, can be hypothesized. Social housing has been shown to reduce the effects of stress [Baker et al., 2012; Gilbert & Baker, 2011] and to the extent that alopecia is partially caused or exacerbated by stress, social housing might be expected to reduce alopecia. One study examining potential treatments for alopecia in cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) found that social manipulations (apparently moving from single housing to pair or gang housing, or changing from one social group to another) was the most effective intervention for reducing alopecia [Harding, 2013].

Although, as described above, there is a small body of research regarding alopecia in rhesus macaques, there is little information regarding alopecia in other macaque species. One study of captive Japanese macaques, (Macaca fuscata) reports alopecia rates of 15-25% [Zhang, 2011]. These rates are somewhat lower than those observed in rhesus, but the effects of sex, age and outdoor access were similar. Kramer and colleagues [2010] report a prevalence rate of 6% for a small group of individually-housed cynomolgus monkeys. To date, little has been reported regarding alopecia in pigtail macaques (Macaca nemestrina).

In this paper we present prevalence rates of alopecia for a colony of laboratory-housed non-human primates at the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC). The WaNPRC houses three macaque species (Macaca mulatta, M. nemestrina, and M. fascicularis) under similar conditions. The goals of this study were to 1) provide normative data on alopecia in laboratory-housed macaques, and to document changes related to sex, species, age and season; 2) to validate the alopecia scoring system utilized at the WaNPRC; 3) to determine whether documented hair pulling was related to an increase in alopecia, and 4) to investigate any effects of housing on alopecia (single-housed vs. pair-housed animals).

We hypothesized that animals who are known hair pullers will be more likely to exhibit alopecia, and that singly-housed animals will have increased alopecia in comparison to pair-housed animals.

Methods

Animals were maintained in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [National Research Council, 2011], participated in the WaNPRC Environmental Enhancement plan and were fed a nutritionally balanced diet, supplemented at least three times per week with additional fruit and produce. The WaNPRC is also accredited by AAALAC (American Association for Assessment of Laboratory Care) International and all research was conducted under protocols approved by the University of Washington institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC). The research adhered to the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Nonhuman Primates.

Subjects

The sample included all rhesus (M. mulatta), pigtail (M. nemestrina), and cynomolgus (M. fascicularis) animals housed singly, in pairs, or in small indoor caged groups of up to four animals at the WaNPRC who were observed in at least one quarterly observation between September 2011 and August 2012 as part of our standard laboratory procedure. All observations for each quarterly period were completed within 36 days. The WaNPRC houses animals at three separate facilities: the Health Sciences Building (HSB), the Infant Primate Research Laboratory (IPRL), and the Western facility (W). Animals from all three facilities were included in the sample. The final sample included 874 animals (Cynomolgus = 75, 26 males; rhesus = 321, 153 males; pigtails = 478, 273 males)

Most animals were observed multiple times. However, some animals were observed fewer times if they entered or were transferred out of the center, or were born or died during the study period. Table I presents the total number of animals of each species observed at each facility during each quarter.

Table I. Animals observed at each period, by species and housing location.

| Sep-Oct1 | Nov-Dec | Mar-Apr | Jul-Aug | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| HSB2 | W | IPRL | HBS | W | IPRL | HSB | W | IPRL | HSB | W | IPRL | |

| Cynomolgus | 20 | 17 | 4 | 51 | 2 | 4 | 25 | 16 | 4 | 24 | 0 | 4 |

| Rhesus | 69 | 101 | 38 | 45 | 93 | 36 | 87 | 125 | 24 | 77 | 146 | 15 |

| Pigtails | 169 | 97 | 70 | 150 | 150 | 54 | 190 | 136 | 47 | 182 | 127 | 48 |

| Total observations at each location | 258 | 215 | 112 | 246 | 245 | 94 | 302 | 277 | 75 | 283 | 273 | 67 |

| Total observations at each period | 585 | 585 | 654 | 623 | ||||||||

Sep-Oct observation dates = 9/12/11 to 10/10/11; Nov-Dec observation dates = 11/21/11- 12/21/11; Mar-Apr observation dates = 3/26/12 – 4/30/12, Jul-Aug observation dates = 7/2/12 – 8/13/12

HSB = Health Sciences Building, W = Western, IPRL = Infant Primate Research Laboratory

Alopecia scoring

Alopecia scores were conducted in conjunction with quarterly observations which is part of our standard laboratory procedure. This monitoring consists of 10-minute observations of animals in their home cages to assess the prevalence of abnormal behaviors including self injury, stereotypy or hair pulling. At the end of the 10-minute observation, the observed animals were rated on an alopecia scale described below. To determine the extent of alopecia we used a scoring system developed by WaNPRC behavioral management and veterinary staff (Rita Bellanca and colleagues, unpublished manuscript). The percentage of the body exhibiting alopecia is estimated based on the “rule of nines,” which is commonly used to assess the extent of injury from burns [Hussain & Ferguson, 2009]. The “rule of nines” splits the body into 11 areas (head, left arm, right arm, chest, abdomen, upper back, lower back, left upper leg, left lower leg, right upper leg, right lower leg) each comprising 9% of the body surface. The tail makes up the final 1%. A body part is counted as affected if any amount of alopecia is present. The number of affected body parts is then added to determine a proportion of body parts affected and an overall alopecia score (0 = 0 affected body parts; 1 = 1-2 affected body parts; 2 = 3-5 affected body parts; 3 = 6-8 affected body parts; and 4 = 9 or more affect body parts). Personnel involved in scoring the animals used for this study had inter-observer reliability scores ranging from .88 to .96 (determined by Cohen's kappa).

Other methods for scoring alopecia in non-human primates have previously been reported for use in field studies or laboratory settings [Berg et al., 2009; Isbell, 1995; Honess et al., 2005; & Zhang, 2011]. With the exception of Isbell [1995] who rated alopecia as either present or absent, the methods use an ordinal scale to quantify coat condition, either for the entire animal [Berg et al., 2009] or for selected body parts [Honess et al., 2005; Zhang, 2011]. Animals can exhibit a wide range of variation in coat condition from one part of the body to another, making rating of the coat condition for the entire animal potentially unwieldy for our purposes, given the large volume of animals that must be assessed. Rating coat condition in only selected locations might be unrepresentative of the animal's true condition. Because of these concerns, we chose to use a method that would quantify the extent of alopecia over the entire body. This scoring system does sacrifice some information regarding the specific quality and total extent of alopecia at each body location. However, the time commitment required to train new observers and to maintain high levels of reliability has been minimal. It also provides an objective score on which to base clinical decisions.

Identification of hair pulling (overgrooming)

Data regarding hair pulling were gathered from quarterly observations and referrals from WaNPRC personnel including veterinary, animal care, behavioral, and research staff. All WaNPRC personnel are trained in the recognition of abnormal behaviors, which includes hair pulling, and to refer animals with behavioral concerns to the behavior case manager (BCM) for further assessment. The behavior is defined as hair pulling or plucking with the hands, feet or mouth and may include ingestion of the hair. The BCM conducts further assessment, implements therapies in conjunction with the veterinary team, and maintains a database of animals referred for behavioral concerns. A list of animals that had been referred in the last two years and had at least one documented observation of hair pulling during that time was obtained from the BCM.

Data analyses

All analyses were performed using SYSTAT® 13 (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). We used chi-square analyses to compare alopecia rates among the three macaque species housed at the WaNPRC (rhesus, pigtail and cynomolgus). Further linear regression analyses investigating factors contributing to alopecia were conducted for rhesus and pigtail macaques. For all analyses, P values that were less than or equal to 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Cynomolgus macaques were not included in the regression analyses due to their small sample size and their much lower levels of alopecia compared to the other two species. For rhesus and pigtails, preliminary analyses using linear regression were conducted separately for each of the four time periods. We chose to conduct the analysis in two stages due to the large number of potential variables and interactions we wished to explore and the non-independence of our data across the observation periods. The animal's alopecia score was the dependent variable. Predictor variables were sex, species, age, and housing location (Western, HSB, IPRL). Age was divided into four age blocks: infants (under 1 year old); juveniles (1-3 years old); adults (4-10 years old); and older adults (over 10 years old). All two-way interactions between sex, species, and age group were included in the model for a total of 14 terms. All terms were initially entered into the model and each term's contribution to the model was assessed by the change in the model fit when that term was removed. Terms were retained if the significance of the change in the model fit was less than or equal to 0.05.

Terms which were significant in at least 3 of the 4 preliminary analyses were then included in the secondary comprehensive analysis presented here. This regression included all observations for rhesus and pigtail animals across all four periods. In addition to the terms retained from the preliminary analyses, time periods 2, 3 and 4 (with period 1 used as the reference group), the interactions of time periods with sex, and the interactions of time periods with species were included in the secondary analysis (Table II). All terms were initially entered into the model and the significance of each term's contribution to the model was assessed in the same manner described for the preliminary analyses. After the best-fitting model was identified, hair pulling status and housing status (pair-housed, single-housed, or other) were entered in the regression to assess their possible contribution to explaining any remaining variance in alopecia score. Finally, two-tailed t-tests were conducted to explore differences in alopecia scores between different age groups of animals assigned to the same research projects.

Table II. Results for comprehensive analysis.

| Predictor (reference category in parenthesis) | B | Effect size (d) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (males) | 0.2541 | 0.25 |

| Species (rhesus) | 0.154 | 0.15 |

| Infants (adult) | -0.868 | -0.88 |

| Juveniles (adult) | -0.296 | -0.30 |

| Older adults (adult) | -0.419 | -0.42 |

| Nov-Dec (Sep-Oct) | 0.207 | 0.21 |

| Mar-Apr (Sep-Oct) | 0.349 | 0.35 |

| Jul-Aug (Sep-Oct) | 0.293 | 0.29 |

| Sex X species | -0.235 | -0.23 |

| Infant X species | -0.361 | -0.36 |

| N | 2276 | |

| R2 | 0.16 | |

| Hair | 0.431 | 0.44 |

| R2 with hair-pulling status | 0.19 | |

| Pair housing | -0.300 | 0.30 |

| R2 with pair housing | .20 |

All beta values were significant at P < 0.001 except for species (P < 0.05) and pair housing (P = 0.001).

Results

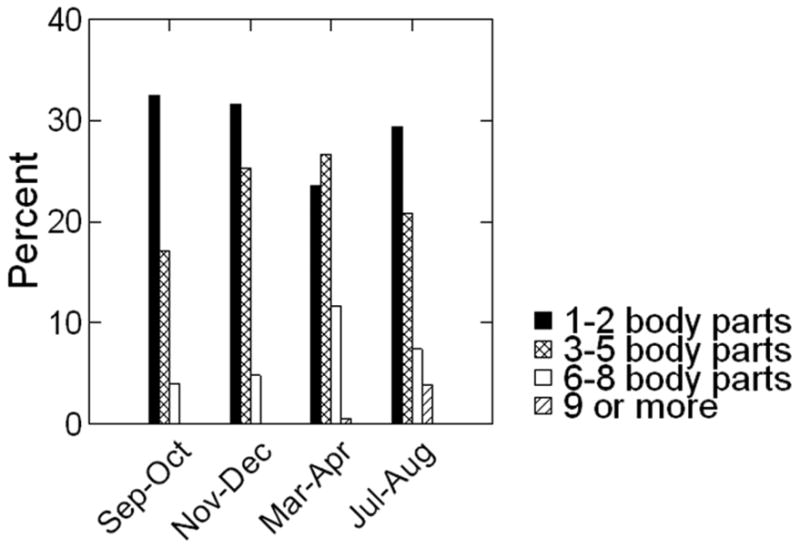

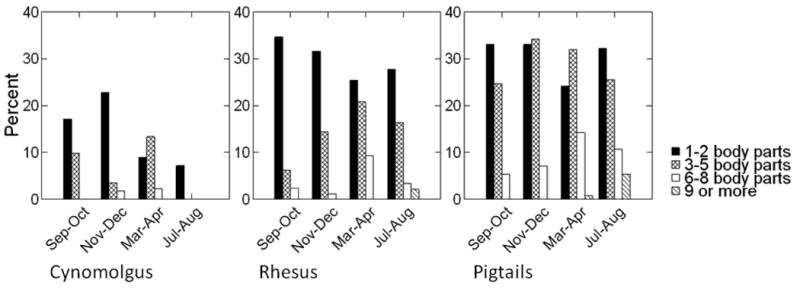

Percentages of animals with each alopecia score across the 4 observation periods are shown for the entire colony in Figure 1, and separately for each species in Figure 2. For the entire colony, percentages of animals with any alopecia (scores of 1 or higher) ranged from 53% to 62% across the 4 periods. Pigtails (63-74%) had higher rates than rhesus (43-55%) while cynomolgus had the lowest rates (7 - 28%). Species differences for alopecia rates were significant at every observation period (Period 1 χ2 = 32.9, df=2, P < 0.001; Period 2: χ2 = 66.7, df = 2, P < 0.001; Period3 χ2 = 44.2, df = 2, P < 0.001; Period 4 χ2 = 71.5, df = 2, P < 0.001; see Fig. 2). For rhesus and pigtails, fewer animals presented with alopecia in the Sep-Oct period, although the difference across periods did not reach significance for rhesus (pigtails χ2 = 13.1, df = 3, P = 0.004; rhesus: χ2= 7.0, df = 3, P = 0.07). For cynomolgus, more animals presented with alopecia in the fall and winter although rate changes were not significant (χ2 = 5.1, df = 3, P = 0.16). Pigtails not only had the highest percentages of animals with any alopecia, at every time period they also had the highest percentages of animals with the most severe alopecia scores (scores 0-1 vs. 2-4; Period 1 χ2 = 38.8, df = 2, P < 0.001; Period 2 χ2 = 55.2, df = 2, P < 0.001; Period 3 χ2 = 28.2, df = 2, P < 0.001; Period 4 χ2 = 39.1, df = 2, P < 0.001).

Figure 1. Percentage of animals with each alopecia score across observation periods.

Figure 2. Percentage of animals receiving each alopecia score at each observation period, by species.

Identified hair pullers comprised 19% of our sample (N = 172). These animals were more likely to be pigtails (χ2 = 13.26, df = 2, P = 0.001), more likely to be female (χ2 = 27.9, df = 1, P < 0.001), and more likely to be housed at our Health Sciences facility (χ2 = 43.4, df = 2, P < 0.001). Hair pullers were less likely to be infants or juveniles (χ2 = 59.0, df = 3, P < 0.001).

Results of preliminary analyses

Six terms from the preliminary analyses were significant in at least 3 of the 4 periods. These included the main effect for sex (Nov-Dec F = 7.0, df = 1,515, P < 0.01; Mar-Apr F = 13.2, df = 1,599, P < 0.001; Jul-Aug F = 11.2, df = 1,586, P = 0.001) and the main effect for all three age blocks (infants: Sep-Oct F = 12.0, df = 1,532, P < 0.005; Nov-Dec F = 8.0, df = 1,515, P = .005; Mar-Apr F = 45.7, df = 1,599, P < 0.001; Jul-Aug F = 12.6, df = 1,586, P < 0.001; juveniles: Nov-Dec F = 4.0, df = 1,515, P < 0.05; Mar-Apr F = 9.8, df = 1,599, P < 0.005; Jul-Aug F = 12.7, df = 1,586, P < 0.001; older adults: Sep-Oct F = 11.5, df = 1,532, P = 0.001; Nov-Dec F = 19.8, df = 1,515, P < 0.001; Mar-Apr F = 31.2, df = 1,599, P < 0.001; Jul-Aug F = 12.9, df = 1,586, P < 0.001) in comparison with the adult (4-10 year old) reference group. Females had significantly higher alopecia scores in comparison to males, and infants, juveniles, and older adults all had significantly lower alopecia scores in comparison with the adult age block. The interactions of sex X species (Sep-Oct F = 10.2, df = 1,532, P = 0.001; Nov-Dec F = 9.4, df = 1,515, P < 0.005; Mar-Apr F = 16.2, df = 1,599, P < 0.001) and infant X species (Sep-Oct F = 8.1, df = 1,532, P = 0.005; Nov-Dec F = 20.9, df = 1,515, P < 0.001; Jul-Aug F = 6.7, df = 1,586, P = 0.01) were also significant. The sex X species interaction was the result of a relatively large sex difference for rhesus animals (with females having more severe alopecia) while pigtails showed minimal differences between the sexes. The infant X species interaction was due to the fact that infants of both species displayed almost no alopecia and species differences only became apparent at older ages.

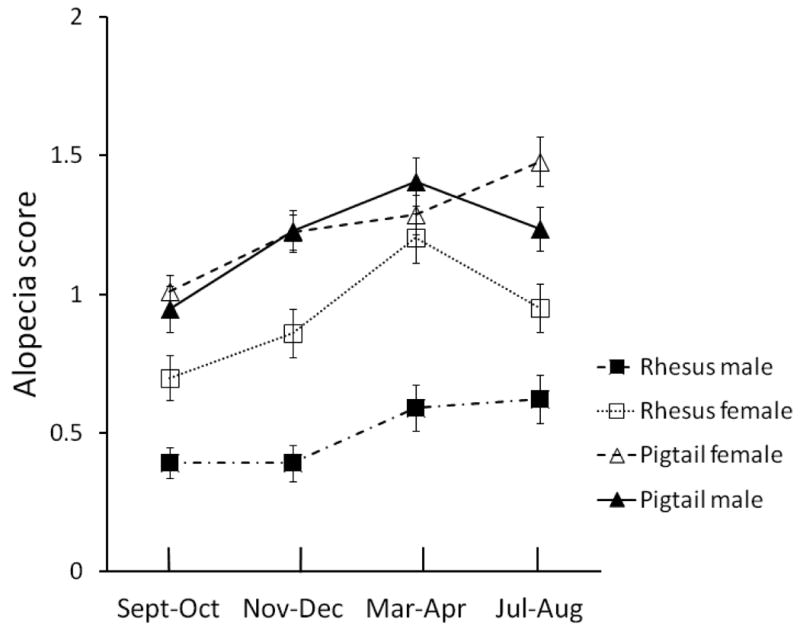

Results of comprehensive analysis

Beta values and effect sizes for terms with significant effects are shown in Table II. Even though the main effect for species was significant in only two preliminary analyses, it was maintained in the comprehensive analysis because it contributed to two significant interactions (sex X species and infant X species) in the preliminary analyses. Females had significantly higher alopecia scores compared to males (F = 30.19, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001), and pigtails had significantly higher alopecia scores in comparison to rhesus (F = 3.92, df = 1,2265, P < 0.05). The sex by species interaction was significant (F = 30.37, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001), indicating that the sex difference was more pronounced in rhesus than in pigtail animals (Fig. 3). Infants, juveniles, and older animals all displayed significantly lower alopecia scores in comparison to the adult reference group (Infants F = 114.43, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001; Juveniles F = 28.98, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001; Older Adults: F = 72.42, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001). In comparison to the Sep-Oct observation period, alopecia became more severe at each of the three subsequent periods (Nov-Dec F = 13.46, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001; Mar-Apr F = 40.94, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001; Jul-Aug F = 28.42, df = 1,2265, P < 0.001). There were no significant interactions of any time period with sex or species.

Figure 3.

Mean Alopecia ratings shown by sex and species. Error bars are standard errors.

Current project assignments of adult and older animals

The finding of decreased alopecia in older animals was unexpected. To determine whether differences in alopecia between our ‘adult’ and ‘older’ animals might be due to different project assignments, we compared animals of both age groups within the same projects. If observed age differences were in fact due to differing project assignments then, when project assignment is held constant, we would expect either that animals of the different age groups would show equivalent levels of alopecia, or that older animals would have increased alopecia in comparison to adults. For the Sep-Oct time period, we identified all projects which enrolled sufficient numbers of animals from both age groups to enable comparison. These were 5 projects involving 136 pigtails (61% of all adult and older pigtails) and 5 projects involving 114 rhesus (64% of all adult and older rhesus). For pigtails, adults had higher alopecia scores in 4 of the 5 projects although none of the differences were significant by t-test (Project 1 t = 0.19, df = 8.9, P = 0.85; Project 2 t = 0.89, df = 8.7, P = 0.40; Project 3 t = 1.37, df = 4.9, P = 0.23; Project 4 t = 1.30, df = 18.0, P = 0.21, Project 5 t = -0.53, df = 24.2, P = 0.60, all tests two-tailed). Results are reported for tests with separate variances. For rhesus, adults had higher alopecia scores than older animals in 4 of the 5 projects and three of these differences were significant by t-test (Project 1 t = 2.59, df = 6.0, P < 0.05, Project 2 t = 2.59, df = 6.0, P < 0.05; Project 3 t = 3.07, df = 9.7, P < 0.05; Project 4 t = 1.10, df = .87, P = 0.3). A t-test was not possible in the 5th project because all ‘adult’ animals in the group (N=3) had alopecia scores of ‘0’. Of the older animals in this project (N=9), six had alopecia scores of ‘0’ and three had alopecia scores of ‘1’.

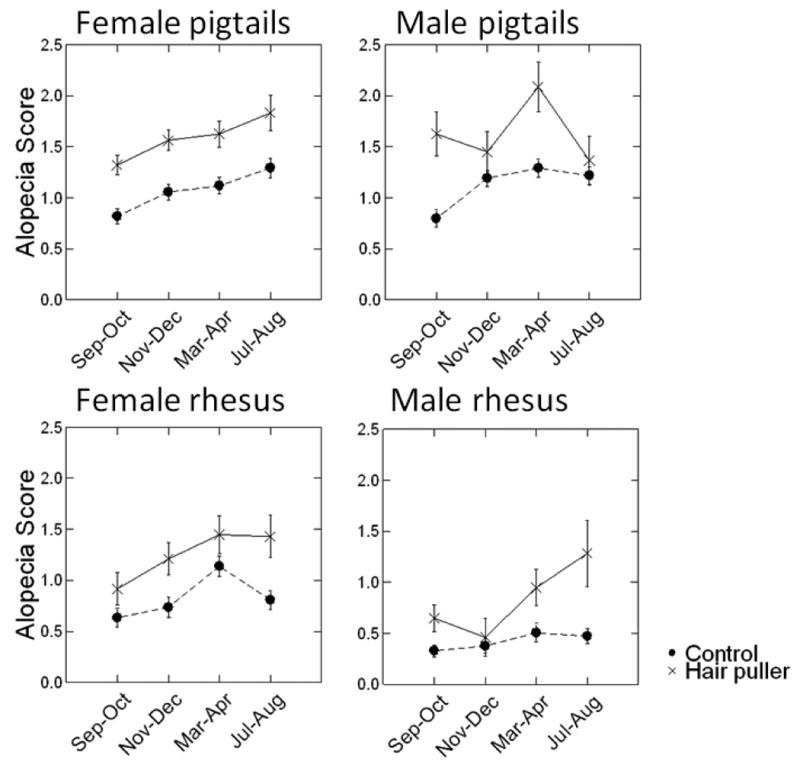

Results for hair pulling and pair-housing on alopecia score

Hair pulling was significantly related to more severe alopecia scores (F = 87,03, df = 1,2263, P < 0.001; Table II and Fig. 4). Being pair housed was significantly related to decreased alopecia (F = 12.14, df = 1,2263, P = 0.001; Table II).

Figure 4. Alopecia scores by hair-pulling status.

Discussion

In this study we compared alopecia rates among three macaque species housed similarly. There were clear differences among the species. Cynomolgus had the lowest rates of alopecia and pigtails had the highest. Due to smaller numbers of cynomolgus in our sample we were not able to investigate species differences in conjunction with effects of sex or housing for this group. Species, sex, time period, and age accounted for 16% of the total variance in alopecia. Hair pulling and housing status, though highly significant, accounted for only small amounts of additional variance (3% and 1% respectively).

Possible causes of species differences

Although multiple causes of alopecia have been identified (see [Novak & Meyer, 2009] for a review), the phenomenon of alopecia in a large percentage of laboratory animals is not well-understood. Documenting and understanding differences in expression of alopecia among closely related species might provide some clues toward an increased understanding of this larger phenomenon. Species differences in alopecia must necessarily be due to differential rates of underlying etiologies between the species, or differential effects on alopecia of underlying etiologies. Of the potential causes of alopecia reviewed by Novak and Meyer [2009], several were statistically (age, seasonal effects, hair pulling) or environmentally (nutritional deficiencies) controlled in our study. Other conditions, such as genetic mutations, are noted to be quite rare and thus could not be the drivers of species differences seen in a large sample. Because clinical symptoms would accompany alopecia of other specific etiologies (bacterial or parasitic infections) and these symptoms were not widely documented in our sample, we are confident that these conditions did not account for a majority of cases in our sample. Remaining potential etiologies that may differentially influence alopecia among species are hormonal differences, autoimmune disorders and stress.

Hormonal differences

Hormone level changes are a major determinant in androgenic alopecia in humans (Inui & Itami, 2011). Because the stump-tailed macaque (Macaca arctoides) shows thinning of scalp hair in post-adolescence (Sundberg et al, 2001), it has been used as an animal model for androgenic alopecia. However, hair loss in the stump-tailed macaque would not appear to be mediated by hormonal changes, as macaques of both sexes show similar degrees of hair loss despite differences in androgen levels. Known hormonal disturbances that are known to cause alopecia in primates are hypothyroidism and hyperadrenocorticism, both of which are rare [Novak & Meyer, 2009]. A third hormonal factor concerns changes during pregnancy and lactation. Only a small percentage of our observations were on pregnant or postpartum animals of either species (8.4% of female pigtail and 4.4% of female rhesus observations). Removing these observations from the data set did not affect any significance decisions in our analysis. Thus, hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and lactation cannot explain species differences found in our sample. It is possible that there are other, as yet unknown, hormonal influences on alopecia in macaques and that these causes differentially affect the species.

Autoimmune disorders

Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disorder described by Novak and Meyer [2009] most typically involving “the development of only a few patches [of alopecia] that disappear very slowly”. This description would appear to fit a large percentage of animals in our study group. Kramer and others [2010] hypothesize that autoimmune disorders are magnified for animals with no early exposure to the outdoors. In their study they found differences in alopecia between a small group of cynomolgus and a larger group of rhesus macaques. However they note that the cynomolgus were born outdoors and this environmental difference might explain lower levels of alopecia, rather than intrinsic differences between the two species. In our study, even though current housing conditions were similar it is possible that past housing conditions varied systematically among the species and influenced alopecia ratings. Since the majority of animals at the WaNPRC are born elsewhere, we do not have information on outdoor exposure for cynomolgus or for most rhesus animals in our sample. We could verify outdoor exposure for a smaller group of our pigtail macaques. A comparison of alopecia for animals known to have been raised continuously indoors, versus animals known to have been born outside did not reveal an overall effect for outdoor exposure. Thus, it would appear that the higher alopecia rates for pigtails are not simply a function of differing early rearing experiences. It is unknown whether this is also true for cynomolgus. It is still possible that even given similar outdoor exposure, species may differ in their susceptibility to autoimmune disorders and this may drive some of the observed differences in alopecia.

Stress

Since animals were housed similarly, the stressors to which animals were exposed related to husbandry procedures should be roughly equivalent. However, stresses related to research project assignment may in fact differ as the species are primarily assigned to separate projects. The relation of project assignment to alopecia is mostly beyond the scope of this paper and awaits further research with a more targeted sample. However, even if one assumes equivalency between stressors experienced by different species, it is probable that species subjectively experience the events in different ways.

Sex differences

In our regression analysis we found that females had more severe alopecia in comparison to males. Although the sex effect was significant in the group overall, pigtails by themselves showed a minimal and inconsistent sex effect across the observation periods. Sex differences in alopecia have been repeatedly documented in rhesus animals but they appear to be absent in pigtails [Runeson et al., 2011]. A common explanation for increased alopecia in rhesus females is hormonal changes associated with pregnancy [Kramer et al., 2010; Zhang, 2011]. Several studies have shown increases in alopecia during pregnancy and lactation [Beisner & Isbell, 2009]. We attempted to look at the effects of pregnancy and lactation in our sample, but due the small numbers of pregnant animals and to the makeup of our sample (pregnant rhesus were imported from other facilities to give birth at WaNPRC) we cannot draw firm conclusions regarding pregnancy and alopecia in our animals. As discussed above, only a small percentage of observations were on pregnant or postpartum animals, and the presence of these animals in our sample did not influence any significance decisions in our study. It is unknown what may be driving sex difference in alopecia in our sample. It is possible that animals of different sexes may be differentially susceptible to autoimmune disorders or to the effects of stress.

Seasonality

Despite the fact that all our animals were housed indoors and most had no access to outdoor light, there were systematic changes in alopecia scores across the observation periods that closely mimic those reported for outdoor housed rhesus [Beisner & Isbell, 2009] and Japanese macaques [Zhang, 2011]. The seasonal pattern also corresponds to descriptions of molt described in free-ranging rhesus macaques by Vessey and Morriosn [1970], although the description of molt in this report involves only the replacement of hair and does not mention alopecia. Steinmetz and others [2006] found similar changes in alopecia across season for animals housed either indoors or outdoors. Overall, scores were lowest in the Sep-Oct period and then rose over the next two observation periods before slightly moderating at the last period (Jul-Aug). There were no significant interactions of either sex or species with observation period.

Two proposed mechanisms for seasonal variation in alopecia have been photoperiod and breeding [Beisner & Isbell, 2009]. Neither of these mechanisms would seem to explain the variation seen in our animals. Photoperiod has been found to vary with alopecia [Steinmetz et al., 2006]. However, photoperiod cannot account for the variation in our sample since animals were housed indoors, most with no access to outdoor light. Hormonal changes associated with breeding have also been proposed. Rhesus are seasonal breeders, and the months of most severe alopecia correspond to months with the highest birth rates. Vessey and Morrison [1970] found that the timing of molt was related (in females) to whether or not the animals gave birth that year, with non-pregnant animals molting earlier. They suggest that the onset of molt may result from a decrease in sex hormones. However, pigtails, who are not seasonal breeders, and males of both species also showed seasonal variation in alopecia.

Changes in alopecia scores over time may also be due to varying environmental conditions. One possibility is humidity level which is known to vary in our housing facilities throughout the year. Partial data from our Western facility shows drier conditions present in the Nov-Dec and Mar-Apr periods. It is possible that our alopecia scores are affected by humidity rather than representing a true seasonal change. Steinmetz and colleagues [2006] reported lower monthly mean humidity was related to more severe alopecia. It is unclear if this may have been an explanatory factor in the seasonal alopecia changes seen in their indoor-housed animals. Aside from this study, potential effects of humidity on alopecia have not been reported in the nonhuman primate research literature.

Age effects

In our study, infant, juvenile, and older adult animals all had significantly lower alopecia scores in comparison with the adult (4-10 year) reference group. There was also a significant interaction between the infant group and species. Infants of both species displayed almost no alopecia and thus, species differences which are not apparent for infants become evident at older ages. Our results are consistent with those reported by other authors documenting higher rates of alopecia in adult animals when compared with juveniles [Kramer et al., 2010; Steinmetz et al., 2006; Zhang, 2011]. Zhang [2011], however, reported alopecia levels in Japanese macaque infants that were similar to those of adult animals. The discrepancy between Zhang's study and our current report may be due to species differences or methodological differences, as Zhang reported on only head and back alopecia. It is worthwhile to note that some mothers in our laboratory have been noted to overgroom their infants, particularly their heads, and this may explain some increased alopecia seen in infants who are housed with their mothers as they were in Zhang's study. Only 14% of the infants in our study were housed with their mothers.

We are not aware of any other reports which document a possible improvement in alopecia in older adult animals. Our findings directly contrast with those of Huneke and colleagues [1996] who found significant dermatologic changes, including hair thinning, in a group of geriatric rhesus monkeys (mean age 25 years). In most studies of alopecia, older animals have not been considered as a separate group. Steinmetz and others [2006] includes elderly animals (up to 26 years old) but they are grouped with younger adults for analysis. Although Steinmetz and colleagues [2006] do not specifically discuss older animals, examination of their scatterplot of age and mean coat condition may corroborate our findings; the oldest animals in their study tend to have better coat condition scores than younger adults. Possible explanations for moderation of alopecia with advanced age might be the diminished contribution of breeding stresses on older animals of both sexes, or diminished overall activity level (including grooming and hair pulling). Animals who reach older ages are probably not a representative subset of younger animals. Therefore it is always possible that older animals differ in substantial ways from the adult group and that it is these differences, not the ages of the animals, that are influencing alopecia ratings. Although all possibilities cannot be ruled out, a most obvious potential difference between ‘adult’ and ‘older’ animals concerns research project assignments. It seems possible that younger animals are assigned to more invasive projects that might have a greater probability of affecting alopecia. We explored this possibility in a subset of animals by examining assignment to current projects with both adult and older animals. Projects were explored separately for rhesus and pigtailed animals. When animals of the two age groups were compared within the same project, older animals still had lower rates of alopecia in 8 of the 10 projects. Thus, lowered alopecia rates in older animals cannot be simply explained by current project assignment differences. Of course, it is still possible that alopecia rates were influenced by other factors such as prior project assignment or colony practices that cull weaker animals at younger ages. Even though we cannot definitively rule out all possible alternate explanations, we believe this result deserves closer scrutiny in other studies of alopecia. It cannot simply be taken for granted that alopecia increases as animals age.

Hair pulling

Confirming our hypothesis, we found that animals identified as hair pullers were more likely to have more severe alopecia. Being a hair puller raised an animal's alopecia score by just under half a standard deviation. These results are somewhat surprising, given that animals needed only one documented instance of hair pulling to be included in our hair pulling group. Despite the strong results, hair pulling does not explain the alopecia of most animals in our group (57 to 69% of animals with alopecia scores of 2 or higher at any given observation were not hair pullers). This conclusion is in line with that from other studies [Luchins et al., 2011; Steinmetz et al., 2005]. These data replicate our collaborative findings on rhesus macaques [Lutz et al., 2013] and extend the conclusions to a second species, pigtail macaques. As Novak and Meyer [2009] outline in their review of alopecia in non-human primates, alopecia has multiple and disparate causes. Hair pulling did not explain alopecia in a majority of animals in our study and these results, along with those of other studies would seem to complicate any attempt to draw a simple association between most alopecia cases and increased stress in laboratory animals. However, we cannot rule out other mechanisms associated with increased stress that may contribute to this condition.

Housing condition

After controlling for the effects of age, sex, species, period and hair pulling, animals that were pair-housed showed significant reductions in alopecia compared to singly-housed animals. This result confirms our hypothesis that pair-housed animals would show a reduction in alopecia in comparison to single-housed animals. As discussed above, pair housing might be expected to decrease alopecia through stress reduction. This result is in line with intervention effects for alopecia of social manipulations reported by Harding [2013]. In our study the effect of pair-housing was highly significant but accounted for only an additional 1 percentage point of variance in the alopecia score. It is perhaps not surprising that the overall effect of social housing is small, since the benefits an animal derives from social housing would be expected to be highly individual, dependent on that animal's characteristics as well as the characteristics of the partner. The translation of that benefit to alopecia improvement is also subject to variability, in part based on the etiology of the alopecia. It would be expected that animals with stress alopecia would show the most benefit. If a typology for stress related alopecia can be reliably identified [e.g., Kramer et al., 2011] it might be worthwhile in future research to examine effects of social manipulations on alopecia of different etiologies.

In conclusion, our study reports alopecia scores across a 12-month period for three macaque species housed under similar conditions. Rates for the three species are markedly different. In addition, a closer analysis of pigtail and rhesus macaques shows that some factors (e.g., sex) are important predictors of alopecia in one species but not another. Both rhesus and pigtails showed variation in alopecia across the seasons although all animals were housed indoors. In contrast to most other published literature, we found that alopecia was not more severe in our older adult animals, and in fact was significantly lower compared with younger adults.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant P51 OD010425 (Thomas Baillie, PI) and by NIH grant R24OD01180-15 to Melinda Novak at the University of Massachusetts through Harvard Medical School, with a subcontract to the University of Washington, Seattle (Julie Worlein, PI). No authors on this study have conflicts of interest related to this research.

References

- Baker K, Bloomsmith M, Oettinger B, Neu K, Griffis C, Schoof V, Maloney M. Benefits of pair housing are consistent across a diverse population of rhesus macaques. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2012;137:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisner B, Isbell L. Ground substrate affects activity budgets and hair loss in outdoor captive groups of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:1160–1168. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisner B, Isbell L. Factors influencing hair loss among female captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2009;119:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Berg W, Jolly A, Rambeloarivony H, Andrianome V, Rasamimanana H. A Scoring System for Coat and Tail Condition in Ringtailed Lemurs, Lemur catta. American Journal of Primatology. 2009;71:183–190. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MH, Baker KC. Social buffering in adult male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta): Effects of stressful events in single versus pair housing. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2011;40:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding K. Behavior treatment of alopecia in Macaca fascicularis: Comparison of outcomes. American Journal of Primatology. 2013;75(Supplement 1):51. [Google Scholar]

- Honess PE, Gimpel JL, Wolfensohn SE, Mason GJ. Alopecia scoring: The quantitative assessment of hair loss in captive macaques. Atla-Alternatives to Laboratory Animals. 2005;33:193–206. doi: 10.1177/026119290503300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huneke RB, Foltz CJ, VandeWoude S, Mandrell TD, Garman RH. Characterization of dermatologic changes in geriatric rhesus macaques. Journal of Medical Primatology. 1996;25:404–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Ferguson C. Assessing the size of burns: Which method works best? Emergency Medicine Journal. 2009;26:664–666. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.081380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui S, Itami S. Molecular basis of androgenetic alopecia: From androgen to paracrine mediators through dermal papilla. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2011;61:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbell L. Seasonal and social correlates of changes in hair, skin, and scrotal condition in Vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) of Amboseli National Park, Kenya. American Journal of Primatology. 1995;36:61–70. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350360105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JA, Mansfield KG, Simmons JH, Bernstein JA. Psychogenic alopecia in rhesus macaques presenting as focally extensive alopecia of the distal limb. Comparative Medicine. 2011;61:263–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Fahey M, Santos R, Carville A, Wachtman L, Mansfield K. Alopecia in Rhesus macaques correlates with immunophenotypic alterations in dermal inflammatory infiltrates consistent with hypersensitivity etiology. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2010;39:112–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchins KR, Baker KC, Gilbert MH, Blanchard JL, Liu DX, Myers L, Bohm RP. Application of the diagnostic evaluation for alopecia in traditional veterinary species to laboratory rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2011;50:926–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz CK, Coleman K, Worlein J, Novak MA. Hair loss and hair pulling in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2013;52:454–457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Eighth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MA, Meyer JS. Alopecia: Causes and treatments, particularly in captive nonhuman primates. Comparative Medicine. 2009;59:18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runeson EP, Lee GH, Crockett CM, Bellanca RU. Evaluating Paint Rollers as an Intervention for Alopecia in Monkeys in the Laboratory (Macaca nemestrina) Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 2011;14:138–149. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2011.551626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Neimeier KA, Kaup FJ. Dermatologic investigation of alopecia in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2005;36:229–238. doi: 10.1638/04-054.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz HW, Kaumanns W, Dix I, Heistermann M, Fox M, Kaup FJ. Coat condition, housing condition and measurement of faecal cortisol metabolites--a non-invasive study about alopecia in captive rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of Medical Primatology. 2006;35:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg JP, King LE, Bascom C. Animal models for male pattern (androgenetic) alopecia. European Journal of Dermatology. 2001;11:321–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey SH, Morrison JA. Molt in free ranging rhesus monkeys, Macaca mulatta. Journal of Mammalogy. 1970;51:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. A non-invasive study of alopecia in Japanese macaques Macaca fuscata. Current Zoology. 2011;57:26–35. [Google Scholar]