Abstract

Vaccination has been the most widely used strategy to protect against viral infections for centuries. However, the molecular mechanisms governing the long-term persistence of immunological memory in response to vaccines remain unclear. Here we show that autophagy plays a critical role in the maintenance of memory B cells against influenza virus infection. Memory B cells displayed elevated levels of basal autophagy with increased expression of genes that regulate autophagy initiation or autophagosome maturation. Mice with B cell-specific deletion of Atg7 (B/Atg7−/−) showed normal primary antibody responses after immunization against influenza, but failed to generate protective secondary antibody responses when challenged with influenza viruses, resulting in high viral loads, widespread lung destruction and increased fatality. Our results suggest that autophagy is essential for the survival of virus-specific memory B cells and the maintenance of protective antibody responses required to combat infections.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccination confers the most effective protection against infections. The ability for the immune system to maintain long-term memory against pathogens is critical for rapid induction of immunity upon later infections1. Initial exposure to antigens leads to the activation and significant expansion of antigen-specific lymphocytes, most of which are removed by programmed cell death after the immune response subsides2–4. However, a small number of these antigen-specific lymphocytes survive and develop into memory cells5,6. The selective retention of antigen-specific memory lymphocytes after an immune response is crucial for the maintenance of long-term immunological memory5–9.

Memory B cells represent a heterogeneous population of quiescent antigen-experienced long-lived B cells7,8,10. Memory B cells can be generated in response to both T cell-dependent and T-cell-independent antigens. Following T-cell-dependent antigen stimulation, the interaction of B cells with T cells leads to the formation of germinal centers (GC), where B cells undergo isotype switching and somatic hypermutations in the immunoglobulin gene7. These antigen-specific GC B cells can give rise to memory B cells or plasma cells7,11,12. After re-encountering the antigens, memory B cells rapidly proliferate and differentiate into antibody secreting plasma cells (ASC) to produce high-affinity antibodies that neutralize antigens8,12,13. Antibody-dependent immune responses are important for the protection against viral infections14. Influenza viruses cause annual epidemic and sometimes pandemic infections that pose major health threats to the human population in the world15,16. Influenza vaccines that offer effective protections typically contain the major viral surface proteins hemaglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase. Induction of memory B cells and neutralizing antibodies against these antigens effectively protects humans from subsequent infection by influenza17–19.

Long-term survival of memory B cells occurs independently of the persistence of the original antigens20. Bcl-2 family members that govern mitochondrion-dependent cell death pathways may regulate memory B cell survival21–23. However, the full mechanisms for the protection of memory B cells from cell death remain unclear. Autophagy is important for maintaining cell survival and plays a critical role in immune regulation24–27. Autophagy may be especially important for sustaining the survival of long-lived cell types, such as neurons28,29. Antibody secreting plasma cells also depend on autophagy for survival through inhibiting ER stress arisen from vigorous immunoglobulin secretion30. The long-lived memory B cells are capable of proliferating and generating high titers of secondary antibody responses after re-encountering the antigens. However, whether autophagy promotes the long-term survival of memory B cells is unknown. Here we present data to show that autophagy is essential for the maintenance of memory B cells against influenza infection. Enhancing autophagy may provide a new means to protect memory B cells and improve the efficacy of vaccination.

RESULTS

Decreased spontaneous cell death and constitutive autophagy in memory B cells

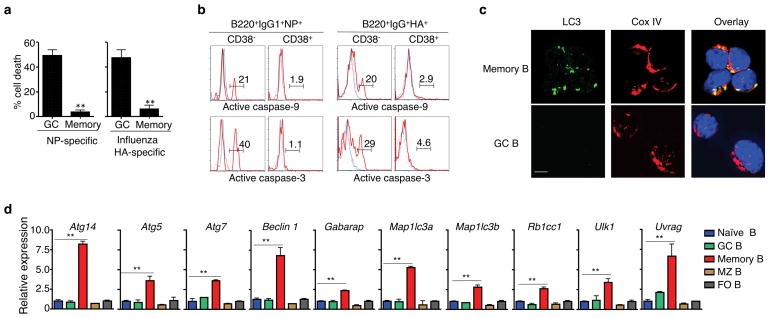

We compared apoptosis signaling in antigen-specific GC and memory B cells from mice immunized with 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (NP-KLH). IgM−IgD−CD11b−Gr-1−CD138− (DUMP−) B220+IgG1+NP+CD38− GC B cells, but not DUMP−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells, showed rapid cell death after in vitro culture (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Accordingly, NP-specific GC B cells displayed the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 by intracellular staining, while NP-specific memory B cells lacked significant caspase activation (Fig. 1b). Similar results were observed in influenza HA-specific memory B cells (Fig. 1a, b). These data suggest that the development of memory B cells from GC B cells is accompanied by increased resistance to cell death.

Figure 1. Decreased spontaneous cell death and caspase signaling but constitutive autophagy in memory B cells.

(a) Percentages of cell loss of NP- or HA-specific memory or GC B cells after in vitro culture. Experiments were performed four times in triplicates using cells from a pool of 15 mice. **P<0.01. (b) Intracellular staining of active caspase-3 or caspase-9 in NP- or HA-specific memory or GC B cells with (red line) or without (blue line) in vitro culture. Data are representative of three experiments. (c) Immunocytochemistry for LC3 and CoxIV staining in NP-specific memory and GC B cells. Data are representative of three experiments. Scale bar: 5 μm. (d) Real-time RT-PCR analyses of autophagy-related genes in naïve mature, germinal center (GC), memory, marginal zone (MZ) and follicular (FO) B cells. Experiments were performed three times in triplicates using cells from a pool of 15 mice. Data in this figure are presented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01 (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

To investigate whether autophagy might protect the long-lived memory B cells, we first measured autophagy in memory B cells by examining the processed form of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) that is characteristic of autophagosome formation31. We detected LC3 punctates in memory B cells, but not GC B cells (Fig. 1c). Compared to naïve B cells and other B cell subsets, real-time RT-PCR showed that memory B cells expressed increased mRNAs of Ulk1 (Atg1), Beclin 1 (Atg6), Rb1cc1, Atg14 and Uvrag that are critical for autophagy initiation32–36, as well as Atg5, Atg7, Map1lc3a, Map1lc3b and Gabarap that are required for autophagosome maturation37 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). These results suggest that memory B cells display constitutively active autophagy.

Requirement for autophagy in memory B cell survival

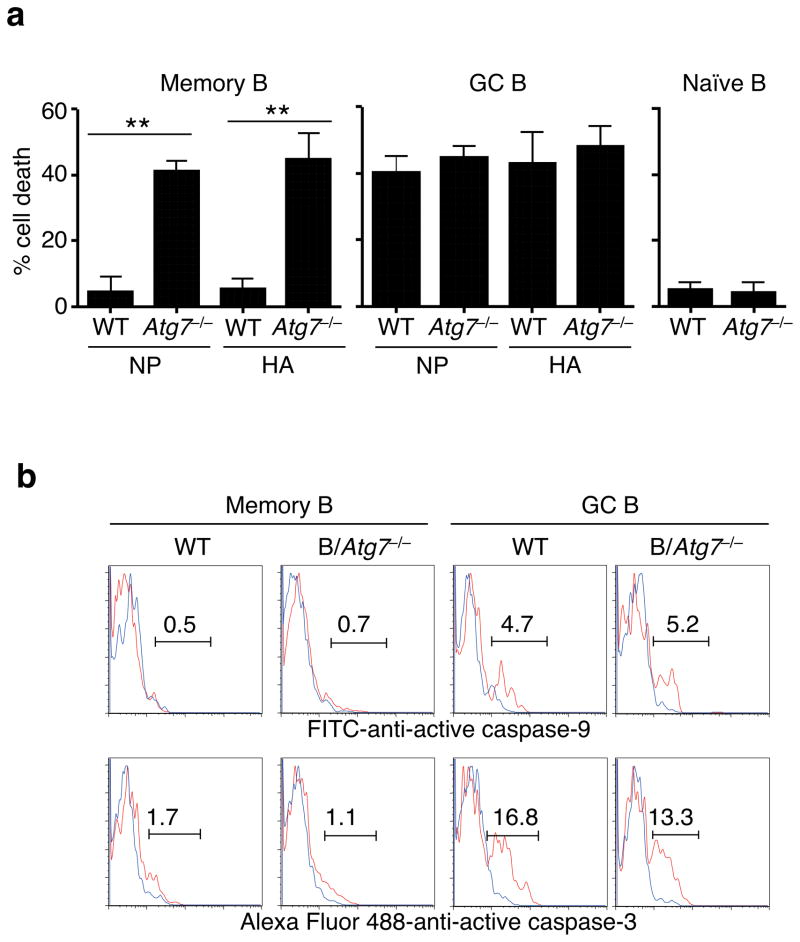

An autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine38, accelerated cell death in memory B cells active in autophagy (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e). To determine whether autophagy protects memory B cells in vivo, we generated B/Atg7−/− mice by crossing CD19-cre mice with Atg7flox mice39 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Although the peritoneal CD5+ B-1a cells were reduced due to autophagy deficiency as observed before in Atg5-deficient mice40, the development of conventional B cells was not affected in B/Atg7−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). Atg7 deficiency increased the turnover rates of B1-a cells but not conventional B cells in vitro or in vivo (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). We found that both NP- and influenza HA-specific Atg7−/− memory B cells underwent significantly increased spontaneous cell death, while cell death in GC B cells was not affected by autophagy deficiency (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3e), suggesting that autophagy protects memory B cells from undergoing cell death.

Figure 2. Increased cell death in autophagy-deficient memory B cells.

(a) Cell death of NP- or HA-specific memory B cells, GC B cells or naïve B cells from B/Atg7−/− mice or CD19-cre mice as wild type (WT) controls after in vitro culture. Experiments were performed three times in triplicates using cells from a pool of 20 mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparison to WT control: **P<0.01 (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test). (b) Intracellular staining of active caspase-3 or caspase-9 in NP-specific memory or GC B cells with (red line) or without (blue line) in vitro culture. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

We found no significant activation of caspase-9 or caspase-3 in Atg7−/− memory B cells undergoing spontaneous cell death (Fig. 2b), suggesting that autophagy deficiency triggers caspase-independent cell death in memory B cells. Although antigen-specific memory B cells and GC B cells showed similar levels of Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 by intracellular staining, memory B cells expressed much more Bcl-2, while deletion of Atg7 did not change the expression of these Bcl-2 family molecules (Supplementary Fig. 4). Higher expression of Bcl-2 mRNA in memory B cells than in GC B cells has been observed previously in mice41. GC B cells in humans express low levels of Bcl-2 and display a propensity for apoptosis42, while Bcl-2 over-expression leads to the accumulation of memory B cells, especially those expressing low-affinity immunoglobulin21. Increased Bcl-2 likely contributes to the resistance of memory B cells to mitochondrion-dependent activation of caspases even in the absence of autophagy.

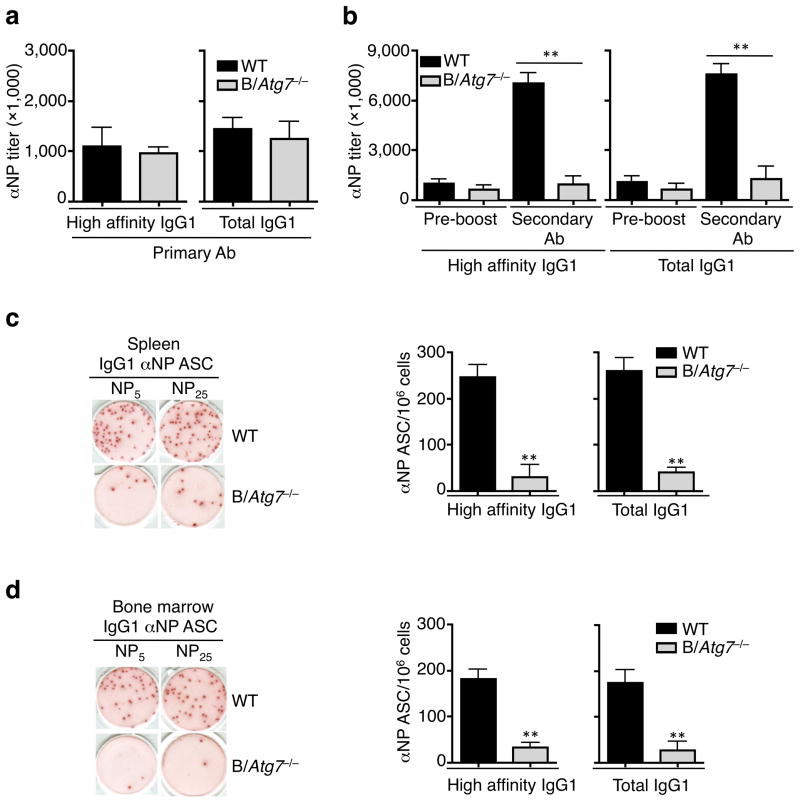

Normal primary but defective secondary antibody responses in the absence of autophagy

We next examined whether autophagy deficiency might affect primary and memory B cell responses. Primary antibody responses at day 14 after immunization with NP-KLH, including the production of high affinity and total (including high- and low-affinity) anti-NP IgG subclasses and anti-NP IgM, were comparable in B/Atg7−/− mice and controls (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). The numbers of NP-specific IgM or IgG1 ASC were similar in the spleen or bone marrow of B/Atg7−/− mice and controls two weeks after primary immunization (Supplementary Figs. 5c and 6a). The induction of B220+GL-7+Fas+ or FITC-anti-GL7-labeled GC B cells were comparable in immunized B/Atg7−/− mice and controls (Supplementary Fig. 6b–d). These results suggest that early primary antibody responses, including germinal center formation, affinity maturation and class switching, are largely normal in B/Atg7−/− mice. A moderate reduction in anti-NP IgG1 antibody in B/Atg7−/− mice six weeks after immunization (Supplementary Fig. 6e) is possibly due to the loss of antibody secreting plasma cells deficient in autophagy30.

Figure 3. Normal primary but defective secondary antibody responses in B/Atg7−/− mice.

(a) Titers of IgG1 anti-NP antibodies detected with NP5 (high-affinity) or NP25 (total) two weeks after immunization (n=10 mice per group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM representative of three independent experiments. Differences between WT and B/Atg7−/− mice are statistically insignificant. (b) Titers of high-affinity and total IgG1 anti-NP antibodies in the sera of immunized mice before boosting or 5 days after antigen boosting. **P<0.01 (n=10 per group in each experiment). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. **P<0.01 (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test). (c, d) ELISPOT for NP-specific IgG1 ASC in the spleen (c) and bone marrow (d) of mice immunized as in (a). A representative image is also shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=10 per group in each experiment) that are representative of three independent experiments. **P<0.01 (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

In contrast to normal early primary antibody responses, we found a severe reduction in secondary anti-NP IgG1 antibody production in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 3b). The number of ASC secreting anti-NP IgG1 was also severely reduced by approximately ten-fold in the spleens and bone marrows of B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 3c, d). This indicates that autophagy is required for secondary antibody responses to T cell-dependent antigens.

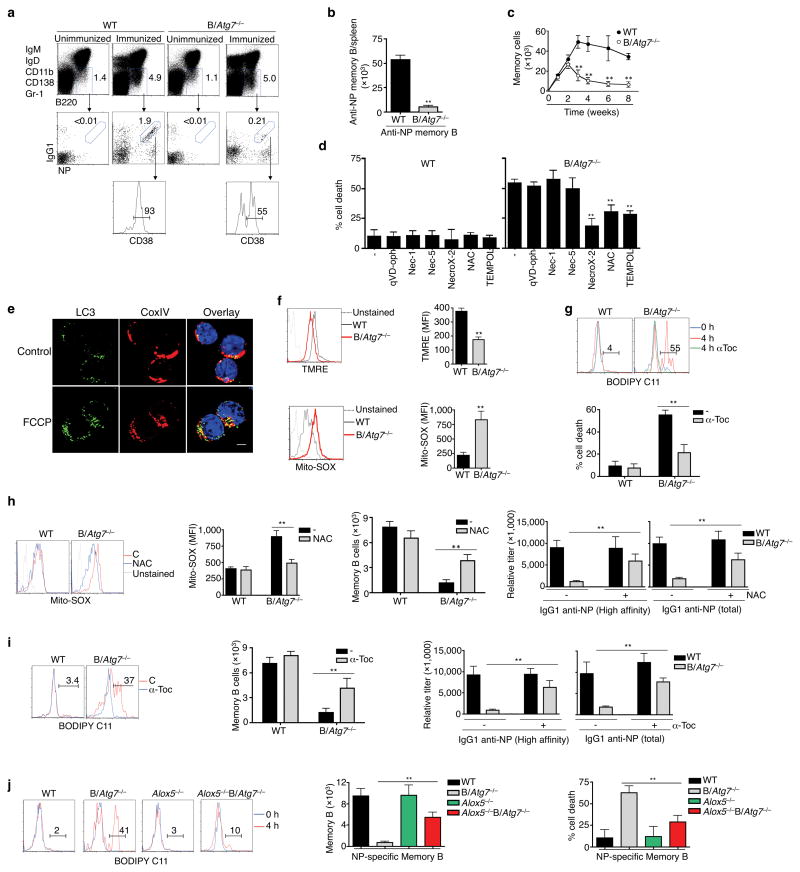

Autophagy deficiency leads to elevated oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and loss of memory B cells

Because of defective secondary antibody responses in B/Atg7−/− mice, we determined whether the generation or maintenance of memory B cells might be defective in these mice. B/Atg7−/− mice showed a severe reduction of NP-specific memory B cells eight weeks after immunization (Fig. 4a, b). The generation of NP-specific memory B cells was normal at weeks 1 and 2 after primary immunization in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4c). However, we detected a rapid decline of memory B cells thereafter in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4c). B/Atg7−/− mice also showed reduced memory B cells in responses to a protein antigen, ovalbumin (Supplementary Fig. 7). These data indicate that memory B cells could be generated initially, but were unable to persist in B/Atg7−/− mice, thereby providing an explanation for the defective secondary antibody responses observed in these mice.

Figure 4. Loss of memory B cells in the absence of Atg7.

(a, b) DUMP−B220+IgG1+CD38+NP+ memory B cells in the spleen of B/Atg7−/− mice or WT controls eight weeks after immunization. Unimmunized mice were used as negative controls (a). Total NP-specific memory B cells in the spleen are presented in (b). **P<0.01 (n=10 mice/group). Data are representative of five independent experiments. (c) The total numbers of NP-specific memory B cells in the spleen of B/Atg7−/− mice or WT controls at indicated days after NP-KLH immunization. Data are representative of two independent experiments. **P<0.01 (n=5 mice/group at each time point). (d) Cell death of NP-specific memory B cells in the presence of different inhibitors after in vitro culture. **P<0.01 (n=3). Data are representative of three experiments. (e) Immunocytochemistry staining for LC3 and CoxIV in NP-specific memory B cells with or without treatment with FCCP. Data are representative of two independent experiments. LC3 punctates/cell: untreated, 10.8 ± 2.4; FCCP, 28.4 ± 4.3. **P<0.01 (n=10). Scale bar: 5 μm. (f) Staining of NP-specific memory B cells with TMRE or Mito-SOX. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is also presented. Data are representative of three independent experiments. **P<0.01 (n=3). (g) Staining with BODIPY in memory B cells after culture for 4 h in the presence or absence of α-Toc. Percentages of positive staining without α-Toc treatment (red line) are shown. Percentages of memory B cell death were also quantified. **P<0.01 (n=6). (h) Mito-SOX staining and total counts of memory B cells from the spleen of NP-KLH-immunized mice injected with NAC or PBS. Induction of NP-specific secondary antibodies was also measured in parallel experiments. **P<0.01 (n=6 mice/group). (i) BODIPY staining and total counts of memory B cells from the spleen of NP-KLH-immunized mice treated with α-Toc. Induction of NP-specific secondary antibodies was also measured in parallel experiments. **P<0.01 (n=6 mice/group). (j) BODIPY staining of NP-specific memory B cells after in vitro culture for 0 or 4 h. Total numbers of memory B cells in the spleen of Alox5−/−B/Atg7−/− and control mice two months after NP-KLH immunization were quantitated. Memory B cell death was measured as in (d). **P<0.01 (n=6). Data in this figure are presented as mean ± SEM (P value are determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

Consistent with a lack of caspase activation in Atg7−/− memory B cells (Fig. 2b), a pan-caspase inhibitor, quinolyl-valyl-O-methylaspartyl-[2,6-difluorophenoxy]-methyl ketone (qVD-oph)43, did not protect the survival of these cells (Fig. 4d). Inhibitors of Rip1-dependent necrosis, including necrostatin-1 and necrostatin-544, also showed no effects (Fig. 4d). In contrast, a necrosis inhibitor targeting oxidative stress, NecroX-245, showed significant inhibition of cell death in Atg7−/− memory B cells (Fig. 4d). Moreover, ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and Tempol46,47, also protected Atg7−/− memory B cells from cell death (Fig. 4d). This indicates that oxidative stress mediates cell death in autophagy-deficient memory B cells.

Autophagy is known to promote the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria48, while dysfunctional mitochondria can produce excessive ROS to induce cell death49. Immunocytochemistry showed that disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential with an uncoupling agent, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP)49, increased the number of autophagosomes that co-localized with mitochondria in memory B cells (Fig. 4e). This supports the possibility that autophagy is involved in the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria in memory B cells. A decrease in mitochondrial membrane potentials in Atg7−/− memory B cells was detected by tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) staining (Fig. 4f), indicating that Atg7−/− memory B cells harbor dysfunctional mitochondria. Increased production of ROS measured by Mito-SOX staining was also detected in Atg7−/− memory B cells (Fig. 4f), suggesting that defective autophagy leads to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and the increased generation of ROS. Lipid peroxidation may induce cell death during oxidative stress50. Significant lipid peroxidation was detected with BODIPY 581/591 C1151 in Atg7−/− memory B cells after in vitro culture (Fig. 4g). Such increases in BODIPY staining were inhibited by α-tocopherol (α-Toc), an anti-oxidant that is efficient in suppressing lipid peroxidation52 (Fig. 4g). Interestingly, α-Toc also inhibited cell death in Atg7−/− memory B cells (Fig. 4g). These results indicate that oxidative stress-induced cell death of autophagy-deficient memory B cells involves lipid peroxidation.

Rescue of Atg7−/− memory B cells by inhibition of ROS and Alox5-dependent lipid peroxidation in vivo

To further determine whether increased ROS contributes to the loss of Atg7−/− memory B cells in vivo, we injected anti-oxidant NAC into B/Atg7−/− and control mice following immunization. We observed that continuous administration of NAC decreased ROS levels in memory B cells from immunized B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4h). NAC also partially rescued memory B cells and secondary antibody responses in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4h), supporting the role for the suppression of ROS production by autophagy in the protection of memory B cell survival. Treatment with α-Toc was effective in suppressing lipid peroxidation in memory B cells in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4i). Injection of α-Toc also partially restored memory B cells and secondary antibody responses in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4i), indicating that elevated lipid peroxidation contributes to the loss of memory B cells in B/Atg7−/− mice.

Alox5 is a major lipoxygenase that catalyzes membrane lipid peroxidation and has been implicated in promoting cell death53–55. We therefore crossed B/Atg7−/− with Alox5−/− mice. We found that additional deletion of Alox5 suppressed the induction of membrane lipid peroxidation in Atg7−/− memory B cells during in vitro culture (Fig. 4j). Deletion of Alox5 also partially rescued memory B cells and secondary antibody responses in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results suggest that Alox5-dependent membrane lipid peroxidation is involved in the accelerated cell death of autophagy-deficient memory B cells.

Impaired memory B cell responses to influenza viruses in B/Atg7−/− mice

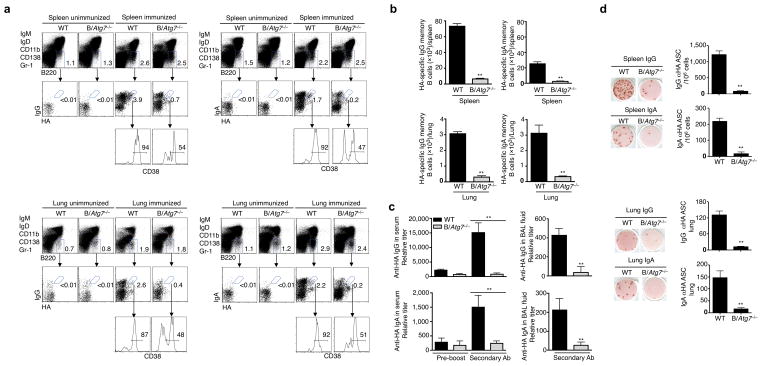

We determined whether the memory immune response against influenza A viruses was dependent on autophagy. Infection with influenza A induced influenza HA-specific IgG or IgA memory B cells in the spleen and lung of wild type mice (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 9). However, these memory B cells were significantly lower in B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 5a, b). The production of secondary anti-HA IgG or IgA antibodies were also severely impaired in B/Atg7−/− mice after re-challenging with the influenza virus (Fig. 5c). Moreover, B/Atg7−/− mice showed significantly decreased IgG or IgA ASC after re-challenging with influenza A (Fig. 5d). In contrast, T cell activation in response to primary or secondary influenza virus infection was not defective in B/Atg7−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 10). Together, these data suggest that autophagy in B cells is essential for the maintenance of protective memory B cell responses against influenza infections.

Figure 5. Defective memory B cell responses to influenza infection in B/Atg7−/− mice.

(a, b) HA-specific memory B cells in the spleen and lung of B/Atg7−/− mice or wild type controls two months after intranasal immunization with influenza virus at a sublethal dose of 7.5 TCID50. Unimmunized mice were used as negative controls (a). The total numbers of NP-specific memory B cells in the spleen and lung are presented (b). Data are representative of three independent experiments. Quantitative analyses are presented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01 (6 mice/group). (c) Mice immunized as in (a) and re-challenged with influenza virus 2 months later. Anti-HA IgG or IgA in the sera or BAL fluids was quantitated 6 days after viral challenge. Antibody titers in the sera before the virus re-challenge are also shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Quantitative analyses are presented as mean ± SEM. **P<0.01 (n=10/group). (d) Anti-HA antibody secreting cells (ASC) in the spleen and lung of mice in (c) were quantitated by ELISPOT. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. **P<0.01 (n=10/group).

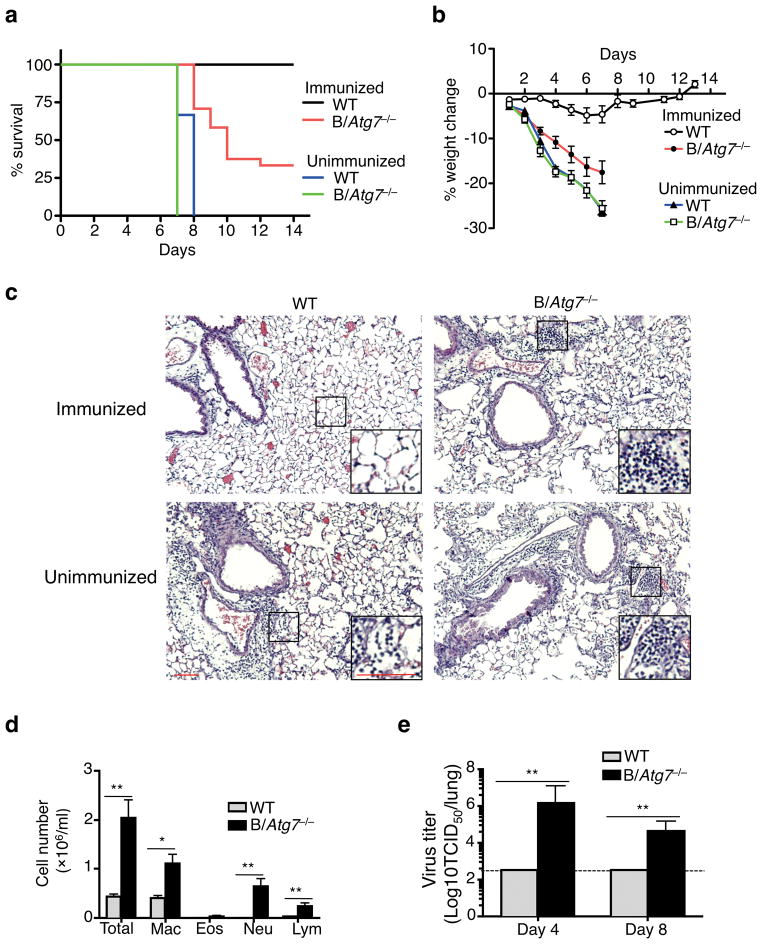

After immunization with a sub-lethal dose of influenza A virus, wild type mice were completely protected from a lethal re-challenge with the virus two months later (Fig. 6a). Wild type immunized mice were also protected from the loss of body weight (Fig. 6b). In contrast, 70% of the immunized B/Atg7−/− mice died by 2 weeks after re-challenging with a lethal dose of influenza A (Fig. 6a). All the immunized B/Atg7−/− mice also showed significant loss of body weight after influenza re-challenge (Fig. 6b). Histological analyses demonstrated extensive lung destruction and leukocyte infiltration in the lungs of the re-challenged B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 6c). Consistently, significant numbers of macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes were found in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of the lethally re-challenged B/Atg7−/− mice (Fig. 6d). Immunized B/Atg7−/− mice displayed 10,000-fold higher viral titers in the lung 4 days after reinfection than wild type controls (Fig. 6e), indicating that B/Atg7−/− mice were unable to efficiently clear the influenza virus. Together, these data suggest that immunization of B/Atg7−/− mice failed to induce protective humoral immunity to control influenza virus re-infection. Despite an important role for antibodies in the protection against influenza infections, T cell responses may also confer certain degrees of protection56–58. B/Atg7−/− mice surviving the reinfection still showed defective anti-HA antibody responses but displayed increased T cell expansion (Supplementary Fig. 10c, e). The increased T cell expansion in these surviving B/Atg7−/− mice could be due to compensatory T cell responses to higher influenza virus loads (Fig. 6e), and may contribute to the survival of a portion of B/Atg7−/− mice after virus reinfection.

Figure 6. B/Atg7−/− mice are defective in mounting protective immunity against influenza virus.

(a, b) B/Atg7−/− mice and WT controls with or without prior influenza immunization were challenged with a lethal dose of influenza virus two months later. The percentage of survival or loss of body weight was quantitated (WT immunized, n=15; B/Atg7−/− immunized, n=21; WT unimmunized, n=10; B/Atg7−/− unimmunized, n=10). B/Atg7−/− versus WT immunized group, P<0.0001 (determined by log-rank test). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Mice with or without influenza virus immunization were infected as in (a) and used for histochemistry analyses of the lung 6 days after virus re-challenge (n=3 per group). Scale bar: 100 μm. The area indicated by the small square was amplified and shown on the lower right corner. Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Quantitation of BAL fluid cells in the lung from mice with prior immunization and re-challenged as in (a). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (n=6 per group) (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test). Data are representative of two independent experiments. (e) Quantitation of virus load in the lung from mice immunized and re-challenged as in (a). Data are representative of two independent experiments. **P<0.01 (day 4: n=5 per group; day 8: n=11 for B/Atg7−/−, n=5 for WT) (determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test).

We next determined whether it is possible to improve memory B cell responses by promoting autophagy. Rapamycin can induce autophagy by inhibiting mTOR59. Indeed, we found that rapamycin increased autophagosome formation and improved the survival of wild type memory B cells (Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). Rapamycin also enhanced the ability of adoptively transferred wild type memory B cells to protect B/Atg7−/− mice against influenza infection (Supplementary Fig. 11d), suggesting that inducing autophagy can promote memory B cell functions. Autophagy is likely to be important for the maintenance of memory B cells with different antigen specificities, such as those specific for influenza neuraminidase (Supplementary Fig. 12a). We also detected autophagosomes in human influenza HA-specific memory B cells (Supplementary Fig. 12b). It may be possible to promote autophagy in human memory B cells and improve protections against influenza viruses after vaccination.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found that autophagy played an essential role in the maintenance of memory B cells. Deletion of Atg7 in B cells led to severe loss of memory B cells and decreased secondary antibody responses against influenza infection. B/Atg7−/− mice immunized with influenza virus remained susceptible to infection, and showed a striking inability to clear the virus that was accompanied by severe lung destruction, loss of body weight and high mortality. Our data therefore demonstrate that autophagy is critical for the maintenance of memory B cells against influenza and potentially other infections.

Memory B cells expressed more Bcl-2 than GC B cells that contributes to the lower susceptibility of memory B cells to apoptosis. Interestingly, overexpression of Bcl-2 favors the accumulation of memory B cells expressing low-affinity IgG21, suggesting that the Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis pathway may affect Ig affinity maturation. In contrast, B/Atg7−/− mice showed loss of memory B cells and defects in the production of both high- and low-affinity IgGs to similar extents, indicating that autophagy may primarily regulate the survival of B cells after GC reactions. Therefore, our study suggests that autophagy inhibits cell death that is distinct from the intrinsic cell death pathway controlled by Bcl-2 family members.

We found no significant caspase activation in memory B cells. Moreover, autophagy deficiency did not induce caspase activation in memory B cells, indicating that the increased cell death in autophagy-deficient memory B cells is different from classic apoptosis that involves caspase activation. We detected decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential and increased ROS in autophagy-deficient memory B cells. Autophagy may be critical for mitochondria quality control to prevent ROS production. The in vivo rescue of memory B cells by α-Toc or deletion of Alox5 in B/Atg7−/− mice suggests that oxidative stress and membrane lipid peroxidation promote cell death in autophagy-deficient memory B cells. Lipid peroxidation may induce organelle stress with the disruption of organelle membranes, such as those of the nucleus, mitochondria and lysosomes50. Disruption of membrane integrity may cause rapid cell death due to organelle malfunctions.

Our data suggest a critical role for autophagy in the maintenance of immunological memory against influenza infection. B cell subsets involved in short-term immune responses do not critically depend on autophagy to maintain their survival. The quiescent antigen-experienced long-lived memory B cells can rapidly proliferate and differentiate into antibody secreting cells upon re-encountering antigens, leading to the production of high-affinity antibodies at high titers that can effectively neutralize pathogens. These long-lived memory B cells would have increased possibilities for accumulating dysfunctional organelles. Our study indicates that autophagy provides a molecular mechanism for the protection of long-lived memory B cells through quality controls of cellular organelles. Promoting autophagy and inhibiting oxidative stress are potentially effective means of improving vaccination against influenza and other viral infections by prolonging the survival of memory B cells.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

CD19-cre knockout-in mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with Atg7flox mice39 to obtain B/Atg7−/− mice. Alox5−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with B/Atg7−/− mice to generate Alox5−/−B/Atg7−/− mice. Sex and age-matched mice on the C57BL/6 background at the age of 6–12 weeks were used at the start of all experiments. For immunization and influenza infection experiments, healthy sex and age-matched mice (6–8 weeks old) were randomly separated into groups for immunization or as unimmunized controls. Mice were identified with tag numbers throughout the experiment. Genotypes corresponding to the different tag numbers were revealed after experiments or when mice need to be sacrificed earlier. At least 5 mice per group were used for each experiment. At least 10 mice per group were used for the infection survival experiments. All mice used for the experiments are included for analyses. The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at Baylor College of Medicine, and experiments were performed according to federal and institutional guidelines and with the approval of the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies

The following antibodies from BD Biosciences were used for flow cytometry: biotinylated antibodies to BP-1 (553159), CD4 (553728), CD8 (553029), IgM (553436), CD11b (553309), CD138 (553713) and GR-1 (553125); PE-conjugated antibodies to B220 (553090), CD5 (553023), CD11b (557397), CD24 (553262), IgD (558597), GR1 (553128), CD138 (553714), IL-17A (559502) and Fas (554258); APC-conjugated antibodies to CD21 (558658), IgM (550676), IgD (560868), CD11b (553312), CD138 (558626) and GR-1 (553129); FITC-conjugated antibodies to GL7 (553666), CD43 (553270), IgA (559354), IgD (553439); PE-Cy7 conjugated anti-CD11b (552820); APC-anti-IFN-γ (554413); Pacific Blue-anti-CD3e (558214); PE-Cy5-anti-CD4 (553050) and APC-Cy7-anti-CD8a (557654); PE-anti-human CD27 (555441); APC-anti-human IgG (550931). From Biolegend: APC-anti-mouse IgG1 (406610), PerCPCy5.5-anti-mouse IgG1(406612), Pacific Blue-anti-CD38 (102720), FITC-anti-mouse IgG (405305), APC-anti-mouse IgG (405308), APC-Cy7-anti-mouse IgG (405316), FITC-anti-Bcl-2 (633504), PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-human CD19 (302230). From eBioscience: PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220 (45-0452-82), PE-anti-IgM (12-5890-83), PE-anti-CD23 (12-0232-82), Biotin-anti-mouse-IgD (13-5993-85), FITC-anti-γδ TCR (11-5711-82), Streptavidin-PE (12-4317-87), PE-Cy7-streptavidin (25-4317-82). From Cell Signaling: anti-active caspase-9 (9509), Alexa fluor 488-anti-Bcl-xL (2767), Alexa fluor 488-anti-active caspase-3 (9665), and Alexa fluor 488-rabbit IgG (4340). From the Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories: normal rabbit IgG (015-000-002) or mouse IgG (011-000-002). From Fitzgerald Industries: anti-Mcl-1 (20R-MR001). From Abgent: anti-LC3 (AP1802a) for immunocytochemistry and anti-Atg7 (AP1813c) for intracellular staining. From Invitrogen: Anti-CoxIV (459600) for immunocytochemistry. From Medical and Biological Laboratories, anti-LC3 (PM036) for intracellular staining.

Immunization with influenza virus or NP-KLH

Sex and age-matched 6 to 8-week old mice were randomly separated into groups for immunization or as unimmunized controls. Mice were administered intranasally with 50 μl influenza A/Hong Kong/8/68 (H3N2)58 (A/HK/68) at a sub-lethal dose of 7.5 TCID50. For intranasal challenge, aliquots of influenza virus were diluted in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) to achieve the indicated number of influenza virus per 50 μl volume. Mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and droplets containing DMEM, and influenza A/HK in DMEM were applied to the nares until a total of 50 μl was inhaled. After two months, mice were re-infected intranasally with influenza A/HK at a dose of 2,500 TCID50 to study immunity to the influenza virus.

Sex and age-matched 6 to 10-week old mice were immunized with 100 μg NP-KLH (Biosearch Technologies) precipitated with 100 μl Imject Alum (Thermo Scientific) intraperitoneally. Two months later, the mice were boosted with 50 μg soluble NP-KLH intraperitoneally. Mouse sera were collected at day 5 following the antigen boost for ELISA. Mouse spleen and bone marrow were harvested for flow cytometry and ELISPOT. For primary antibody responses, antibody production in the sera and ASC in the spleen and bone marrow were measured two weeks after immunization of mice with alum-precipitated NP-KLH. Mice were also immunized with 100 μg OVA (Sigma) precipitated with 100 μl Imject Alum intraperitoneally to examine OVA-specific memory B cells.

In some experiments, mice immunized with NP-KLH were injected intraperitoneally with NAC (100 mg kg−1 body weight) or α-Toc (1,000 mg kg−1) once every two days for 8 weeks. B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells in the spleen were quantitated. In parallel experiments, mice were then boosted with 50 μg soluble NP-KLH intraperitoneally. Sera were collected 5 days later and used to determine the titers of secondary antibodies by ELISA.

Real-time RT-PCR

B220+CD23low/−CD21high Marginal zone (MZ) B cells, B220+CD23+CD21− follicular (FO) B cells and B220+IgMlowIgD+CD23+IgG− naïve mature B cells were sorted from unimmunized mouse spleen by flow cytometry. B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells and B220+IgG1+NP+CD38− GC B cells were sorted from mouse spleen 2 months after immunization with NP-KLH. Propidium iodide (PI; 2 μg ml−1) was included in all the sorting to exclude dead cells using the UV laser. B220+/lowCD23−CD11b+CD5+ B1-a cells and B220+CD23+CD5− B-2 cells from the peritoneum were also sorted. RNA extracted from the cells was used to prepare cDNA with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed using Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix with specific primers for autophagy genes or 18S rRNA from the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Kit (AB Applied Biosystem) in the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System. The assay IDs for the primers of the analyzed genes are: Mm00504340_m1 (Atg5), Mm00512209_m1 (Atg7), Mm01265461_m1 (Beclin 1), Mm00437238_m1 (Ulk1), Mm00456545_m1 (Rb1cc1), Mm00458725_g1 (Maplc3a), Mm00782868_sH (Maplc3b), Mm00490680_m1 (Gabarap), Mm00553733_m1 (Atg14) and Mm00724370_m1 (Uvrag). Relative gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA. The expression of autophagy-related genes in B cell subsets relative to resting mature B cells was calculated.

In vivo 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling and adoptive transfer of B cells

B/Atg7−/− and control mice (10–12 weeks old) were fed with 1 mg ml−1 BrdU (Sigma) in drinking water as described60. Fresh BrdU were replaced every 2 days. At the indicated time points, splenocytes and peritoneal cavity cells were harvested and stained for B220+CD23+IgMlowIgD+ naïve B cells and B220+/lowCD5+CD11b+ B-1a cells, respectively. The cells were then permeabilized and used for intracellular BrdU staining using the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacture’s instructions. Samples were then analyzed on a LSRII flow cytometer.

To measure the survival of naïve B cells in vivo, B220+CD23+IgMlowIgD+ naïve cells from CD45.2 B/Atg7−/− mice and controls were sorted on a BD FACS Aria cell sorter and adoptively transferred into CD45.1 mice intravenously (2×106 cells/mice). The number of transferred CD45.2+B220+IgMlowIgD+ naïve cells in the spleens of CD45.1 recipients was measured by flow cytometry at indicated time points.

Adoptive transfer of memory B cells

Wild type or B/Atg7−/− mice infected with 50 TCID50 of the influenza virus were used as donors of WT or Atg7−/− memory B cells two months after infection. B/Atg7−/− mice that received 7.5 TCID50 of the influenza virus three months ago were used as recipients of the memory B cells. HA-specific WT or Atg7−/− memory B cells were sorted from pooled spleens and lungs from influenza infected donor mice and adoptively transferred intravenously (104/mice) into B/Atg7−/− recipient mice. Sorted B220+CD23+IgMlowIgD+ naïve B cells (2×105/mouse) from unimmunized B/Atg7−/− mice were co-injected as filler cells to minimize cell loss during injection. One day after the transfer, B/Atg7−/− recipients were re-infected with a lethal dose (2,500 TCID50) of influenza virus. Some groups were treated intraperitoneally with rapamycin61 (LC Laboratories; 75 μg kg−1) daily from day −1 to day 13 during infection (10 mice/group). Weight loss and survival of the recipient mice were monitored for 14 days.

Determination of lung viral titers

On days 4 and 8 after infection with influenza A, mouse lungs were collected and rinsed in sterile water to lyse excess red blood cells. Lungs were resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and homogenized using a glass bead beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Samples were diluted in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles’ medium containing 0.05 % trypsin (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), centrifuged for 10 min at 9,000 rpm, and supernatants were serially diluted in 96-well round-bottom plates (Fisher Scientific, Atlanta, GA). Samples were then transferred to 96-well round-bottom plates containing MDCK (Madin Darby canine kidney) cell monolayers. Lung dilutions and MDCK cells were allowed to incubate for 4 days, and then visualized for characteristic adherence of turkey red blood cells (Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, MA).

Counting the Number of Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid Cells

BAL fluid collection and quantitation of airway cells were carried out as previously described62. BAL cells were collected by serially instilling and withdrawing 0.8 ml aliquots of PBS (pH 7.2) twice from the tracheal cannula. Aliquots of 105 cells were centrifuged onto glass slides, stained using modified Giemsa, and used to determine the absolute numbers of BAL fluid cells.

Cell death analyses

Mice were immunized with NP-KLH or influenza A viruses as above. Splenocytes were collected 5–8 weeks later and incubated with biotinylated antibodies to CD4, CD8, IgM, IgD, CD11b, CD138 and Gr-1 (DUMP), followed by incubation with streptavidin-MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec) to deplete non-B cells, B cells without Ig class switching and plasma cells. NP-specific memory cells were then stained with APC-anti-mouse IgG1, PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220, Streptavidin-PE, Pacific Blue-anti-CD38 and FITC-NP-BSA (Biosearch Technologies). HA-specific memory cells from influenza-infected mice were then stained with FITC-anti-IgG, PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220, Streptavidin-PE, Pacific Blue-anti-CD38 and PE Cy7-conjugated HA. PI was also added to exclude dead cells using the UV laser in a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). PI−DUMP−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells, PI−DUMP− B220+IgG1+NP+CD38− GC B cells, PI−B220+IgG+HA+CD38+ memory B cells and PI−B220+IgG+HA+CD38− GC B cells were sorted on a BD FACS Aria or MoFlo cell sorter. The purity of sorted cells was between 96% and 99%. Sorted cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 complete medium for 0 or 6 h in 96-well plates (104 cells/well). Live cells with exclusion of PI staining was determined by flow cytometry63. Percentage of cell loss of live cells was calculated as follows: (Bcontrol − Bcultured)/Bcontrol × 100%, with Bcontrol and Bcultured represent B cells without or with culture in vitro. Alternatively, PI−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells were sorted from 20 to 40 mice immunized with NP-KLH as above. The cells (104 cells/well) were cultured in the absence or presence of 5 μM NecroX-2, 10 μM Necrostatin-1, 10 μM Necrostatin-5 (Enzo Life Sciences), 5 μM N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), 5 μM TEMPOL, 100 μM α-tocopherol (α-Toc), 10 mM 3-MA or 200 μM qVD-oph (Sigma) at 37 °C for 6 h. PI was added to the cells and PI− live cells were quantitated by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Influenza A H3N2 HA, H3N2 NA and H1N1 HA (Sino Biological) were conjugated to PE-Cy7 using the Easylink PE/Cy7 conjugation kit (Abcam). To detect HA-specific memory B cells, spleen cells or lung homogenate cells were stained with PE-conjugated antibodies to CD11b, IgM, IgD, GR1 and CD138 (DUMP), APC-anti-mouse IgG, FITC-anti-mouse IgA, PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220, Pacific blue-anti-CD38 and PE-Cy7-HA or PE-Cy7-NA. PI was added at the end to exclude dead cells. PI−DUMP−B220+IgG+HA+CD38+ or PI−DUMP−B220+IgG+NA+CD38+ memory B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. A total of 4×106 live cells were collected in the flow cytometer for analyses. To detect NP-specific memory B cells, spleen cells were stained with PE-conjugated antibodies to CD11b, IgM, IgD, Gr1 and CD138 (DUMP), APC-anti-mouse IgG1, PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220, Pacific blue-anti-CD38 and biotinylated NP-BSA (Biosearch Technologies) followed with PE-Cy7-streptavidin. PI was added to exclude PI+ dead cells. A total of 4×106 live cells were collected in the flow cytometer for analyses. Typically, between 500 and 4,000 wild type memory B cells or 250 and 2,200 Atg7−/− memory B cells were gated for further analysis at different time points. OVA-specific memory B cells were detected by staining with PE-conjugated antibodies to CD11b, IgM, IgD, Gr1 and CD138, PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-B220, APC-Cy7-anti-mouse IgG, Pacific blue-anti-CD38 and Alexa fluor 647-OVA (Invitrogen). PI−DUMP−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ or PI−DUMP− B220+IgG+OVA+CD38+ memory B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. A total of 4×106 live cells were collected in the flow cytometer for analyses.

Anti-active caspase-9, anti-Mcl-1, and normal rabbit or mouse IgG were labeled with FITC using the Easylink FITC conjugation kit (Abcam). B220+ B cells were purified from the spleen with anti-B220 MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured in RPMI medium with 0.5% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C for 0 or 9 h. Cells were stained with surface markers as above and incubated in Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences), followed by intracellular staining with Alexa fluor 488-anti-active caspase-3, FITC-anti-active caspase-9 or isotype controls. Freshly isolated cells were also stained with FITC-anti-Bcl-2, Alexa fluor 488-conjugated anti-Bcl-xL or FITC-anti-Mcl-1. The cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry with a total of 4×106 cells collected. Between 2×103 and 4×103 of gated memory B cells or GC B cells were acquired for FACS analysis.

To measure mitochondrial membrane potential or ROS, B220+ cells from the spleen of different mice immunized with NP-KLH were isolated by MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were incubated with 25 nM TMRE or 5 μM Mito-SOX (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were then stained with PerCPCy5.5-anti-IgG1, Pacific blue-anti-CD38, biotinylated NP-BSA and PE-Cy7-streptavidin, and APC-conjugated antibodies to IgM, IgD, CD11b, CD138 and Gr-1 (DUMP), and analyzed by flow cytometry. TMRE or Mito-SOX staining (FL2) of DUMP−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells was plotted.

To detect lipid peroxidation, B220+ cells from pooled mouse spleens were isolated as above and stained with PerCPCy5.5-anti-IgG1, Pacific blue-anti-CD38, biotinylated NP-BSA and PE-Cy7-streptavidin, and APC-conjugated antibodies to IgM, IgD, CD11b, CD138 and Gr-1 (DUMP). PI was added to exclude dead cells. PI−DUMP−B220+IgG1+NP+CD38+ memory B cells were sorted. Cells (104/treatment) were treated with or without α-Toc for 4 hours, and cultured at 37 °C for 1 h with 2 μM BODIPY 581/581 C11 (Life Technologies), which integrates into the membranes and generate green (FL1) fluorescence after oxidation51.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Sera with serial dilutions were added to 96-well plates coated with 5 μg ml−1 NP5-BSA (for detecting high-affinity anti-NP) or NP25-BSA (for detecting both high- and low-affinity anti-NP) obtained from Biosearch Technologies and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (Southern Biotechnology). The plates were developed with TMB peroxidase substrate kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and optical densities at 450 nm were measured. A mixture of sera from wild type mice immunized with NP-KLH was used to establish standard curves in each plate and antibody levels were shown as relative titers. Influenza A H3N2 specific antibodies in the sera or BAL fluid were measured similarly as above except that 96-well plates were coated with 2 μg ml−1 H3N2 HA or H3N2 NA (Sino Biological) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies against mouse IgG and IgA (Southern Biotechnology) were used.

ELISPOT

MultiScreen 96-well Filtration plates (Millipore) were coated with 20 μg ml−1 NP5-BSA or NP25-BSA. Splenocytes or bone marrow cells (1–5×105/well) were then added to the plates and incubated at 37 °C for 5 h. The cells were lysed with H2O and the wells were probed with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 or anti-mouse IgM (Southern Biotechnology), followed by development with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbzole (Sigma). To detect HA-specific antibody forming cells, the MultiScreen Filtration plates were coated with 10 μg ml−1 H3N2 HA (Sino Biological). Splenocytes or lung cells (1–5×105/well) were then added to the plates and incubated at 37 °C for 5 h. The cells were lysed with H2O and the wells were probed with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-mouse IgA (Southern Biotechnology) and developed as above.

Human B cell isolation and analyses

Human lung single cell suspension was prepared from donors undergoing lung resection at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center as described64. Briefly, fresh lung tissue was cut into 0.1 cm pieces in Petri dishes and treated with 2 mg ml−1 collagenase D (Roche Pharmaceuticals) in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C. Single cells were extracted by pressing digested lung tissue through 40 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon) followed by lysis of red blood cells in ACK lysis buffer (Sigma). Lung cells were then stained with PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-CD19, PE-anti-CD27, APC-anti-IgG, and HA3-PE-Cy7. PI−CD19+CD27+IgG+ HA+ memory B cells and PI−CD19+CD27−IgG− naïve cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) with over 95% pure cell populations. The sorted cells were used for immunocytochemistry staining. The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine and informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Frozen spleen sections (5 μM) were stained with PE-anti-B220 and FITC-anti-GL7. The sections were examined with a BX-51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus). Sorted B220+IgG1+CD38+NP+ memory B cells with or without cultured in the absence or presence of 10 μM FCCP for 1 h were added to slides by cytospin. The cells were fixed, incubated with mouse anti-COX IV and a rabbit antibody to processed LC3 (Abgent), followed by staining with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). The nucleus was counter-stained with DAPI. The cells were then analyzed using a SoftWorx Image deconvolution microscope (Applied Precision).

Statistic analyses

Data were presented as the mean ± SEM, and P values were determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism software and are included in Figure legends. Significant statistic differences (P<0.05 or P<0.01) are indicated. Survival times of virally infected mice were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival estimate using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for curve comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Komatsu of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science for providing Atg7-flox mice. We thank M. Schaefer and L.-Z. Song for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health to J.W. (R01 GM087710), M.C. (R01DK083164), D.B.C and F.K. (R01HL117181), and a VA merit award (to D.B.C and F.K.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

M.C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; M.J.H. performed viral infection, determined lung pathology and analyzed data; H.S. and L.W. performed experiments; X.S assisted with experiments; B.E.G provided the virus and advised on viral titration; D.B.C. and F.K. advised on influenza experiments and provided human samples; J.W. designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccination. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:509–517. doi: 10.1038/ni.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenardo M, et al. Mature T lymphocyte apoptosis--immune regulation in a dynamic and unpredictable antigenic environment. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:221–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krammer PH, Arnold R, Lavrik IN. Life and death in peripheral T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:532–542. doi: 10.1038/nri2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gourley TS, Rouse BT, Ahmed R. Differentiation of memory B and T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Progressive differentiation and selection of the fittest in the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:982–987. doi: 10.1038/nri959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHeyzer-Williams M, Okitsu S, Wang N, McHeyzer-Williams L. Molecular programming of B cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:24–34. doi: 10.1038/nri3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurosaki T, Aiba Y, Kometani K, Moriyama S, Takahashi Y. Unique properties of memory B cells of different isotypes. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:104–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasturi SP, et al. Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature. 2011;470:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridderstad A, Tarlinton DM. Kinetics of establishing the memory B cell population as revealed by CD38 expression. J Immunol. 1998;160:4688–4695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shlomchik MJ, Weisel F. Germinal center selection and the development of memory B and plasma cells. Immunol Rev. 2012;247:52–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton DR. Antibodies, viruses and vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:706–713. doi: 10.1038/nri891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakaya HI, et al. Systems biology of vaccination for seasonal influenza in humans. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:786–795. doi: 10.1038/ni.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu X, et al. Neutralizing antibodies derived from the B cells of 1918 influenza pandemic survivors. Nature. 2008;455:532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature07231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Riet E, Ainai A, Suzuki T, Hasegawa H. Mucosal IgA responses in influenza virus infections; thoughts for vaccine design. Vaccine. 2012;30:5893–5900. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez Lorenzo MM, Fenton MJ. Immunobiology of influenza vaccines. Chest. 2013;143:502–510. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruyama M, Lam KP, Rajewsky K. Memory B-cell persistence is independent of persisting immunizing antigen. Nature. 2000;407:636–642. doi: 10.1038/35036600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith KG, et al. bcl-2 transgene expression inhibits apoptosis in the germinal center and reveals differences in the selection of memory B cells and bone marrow antibody-forming cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:475–484. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer SF, et al. Proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim is essential for developmentally programmed death of germinal center-derived memory B cells and antibody-forming cells. Blood. 2007;110:3978–3984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clybouw C, et al. Regulation of memory B-cell survival by the BH3-only protein Puma. Blood. 2011;118:4120–4128. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deretic V. Autophagy in infection. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lum JJ, et al. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell. 2005;120:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pengo N, et al. Plasma cells require autophagy for sustainable immunoglobulin production. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:298–305. doi: 10.1038/ni.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabeya Y, et al. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2805–2812. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell RC, et al. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ncb2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang XH, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hara T, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang C, et al. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–699. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. 3-Methyladenine: specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:1889–1892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller BC, et al. The autophagy gene ATG5 plays an essential role in B lymphocyte development. Autophagy. 2008;4:309–314. doi: 10.4161/auto.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi Y, Ohta H, Takemori T. Fas is required for clonal selection in germinal centers and the subsequent establishment of the memory B cell repertoire. Immunity. 2001;14:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebecque S, de Bouteiller O, Arpin C, Banchereau J, Liu YJ. Germinal center founder cells display propensity for apoptosis before onset of somatic mutation. J Exp Med. 1997;185:563–571. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caserta TM, Smith AN, Gultice AD, Reedy MA, Brown TL. Q-VD-OPh, a broad spectrum caspase inhibitor with potent antiapoptotic properties. Apoptosis. 2003;8:345–352. doi: 10.1023/a:1024116916932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Degterev A, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HJ, et al. NecroX as a novel class of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and ONOO scavenger. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1813–1823. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell J, Jiang H, Berry L, Meyrick B. Effect of antioxidants on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated induction of mangano superoxide dismutase mRNA in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1996;169:333–340. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199611)169:2<333::AID-JCP12>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddan JR, et al. The superoxide dismutase mimic TEMPOL protects cultured rabbit lens epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide insult. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:543–554. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Mitochondria and the autophagy-inflammation-cell death axis in organismal aging. Science. 2011;333:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1201940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gottlieb E, Vander Heiden MG, Thompson CB. Bcl-x(L) prevents the initial decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent reactive oxygen species production during tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5680–5689. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5680-5689.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gueraud F, et al. Chemistry and biochemistry of lipid peroxidation products. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:1098–1124. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.498477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drummen GP, van Liebergen LC, Op den Kamp JA, Post JA. C11-BODIPY(581/591), an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent lipid peroxidation probe: (micro)spectroscopic characterization and validation of methodology. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:473–490. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Catala A. Lipid peroxidation modifies the picture of membranes from the “Fluid Mosaic Model” to the “Lipid Whisker Model”. Biochimie. 2012;94:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maccarrone M, Catani MV, Agro AF, Melino G. Involvement of 5-lipoxygenase in programmed cell death of cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:396–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Costa-Junior HM, et al. ATP-induced apoptosis involves a Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 and 5-lipoxygenase in macrophages. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;88:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ezekwudo DE, Wang RC, Elegbede JA. Methyl jasmonate induced apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma cells via 5-lipoxygenase dependent pathway. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2007;6:267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamouda T, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and stability of a novel intranasal nanoemulsion-adjuvanted influenza vaccine in a murine model. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:585–594. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.7.11818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKinstry KK, et al. IL-10 deficiency unleashes an influenza-specific Th17 response and enhances survival against high-dose challenge. J Immunol. 2009;182:7353–7363. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tai W, et al. Multistrain influenza protection induced by a nanoparticulate mucosal immunotherapeutic. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:197–207. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ. Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:304–312. doi: 10.1038/nrd2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forster I, Rajewsky K. The bulk of the peripheral B-cell pool in mice is stable and not rapidly renewed from the bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4781–4784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Araki K, et al. mTOR regulates memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature08155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kheradmand F, et al. A protease-activated pathway underlying Th cell type 2 activation and allergic lung disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:5904–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hornung F, Zheng L, Lenardo MJ. Maintenance of clonotype specificity in CD95/Apo-1/Fas-mediated apoptosis of mature T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:3816–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grumelli S, et al. An immune basis for lung parenchymal destruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.