Abstract

Reciprocal interactions between tumor and stromal cells propel cancer progression and metastasis. An understanding of the complex contributions of the tumor stroma to cancer progression necessitates a careful examination of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is largely synthesized and modulated by Cancer Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs). This structurally supportive meshwork serves as a signaling scaffold for a myriad of biological processes and responses favoring tumor progression. The ECM is a repository for growth factors and cytokines that promote tumor growth, proliferation, and metastasis through diverse interactions with soluble and insoluble ECM components. Growth factors activated by proteases are involved in the initiation of cell signaling pathways essential to invasion and survival. Various transmembrane proteins produced by the cancer stroma bind the collagen and fibronectin-rich matrix to induce proliferation, adhesion and migration of cancer cells, as well as protease activation. Integrins are critical liaisons between tumor cells and the surrounding stroma, and with their mechano-sensing ability induce cell signaling pathways associated with contractility and migration. Proteoglycans also bind and interact with various matrix proteins in the tumor microenvironment to promote cancer progression. Together, these components function to mediate crosstalk between tumor cells and fibroblasts ultimately to promote tumor survival and metastasis. These stromal factors, which may be expressed differentially according to cancer stage, have prognostic utility and potential. In this review, we examine changes in the ECM of cancer associated fibroblasts induced through carcinogenesis, and the implications of these changes on cancer progression.

Introduction

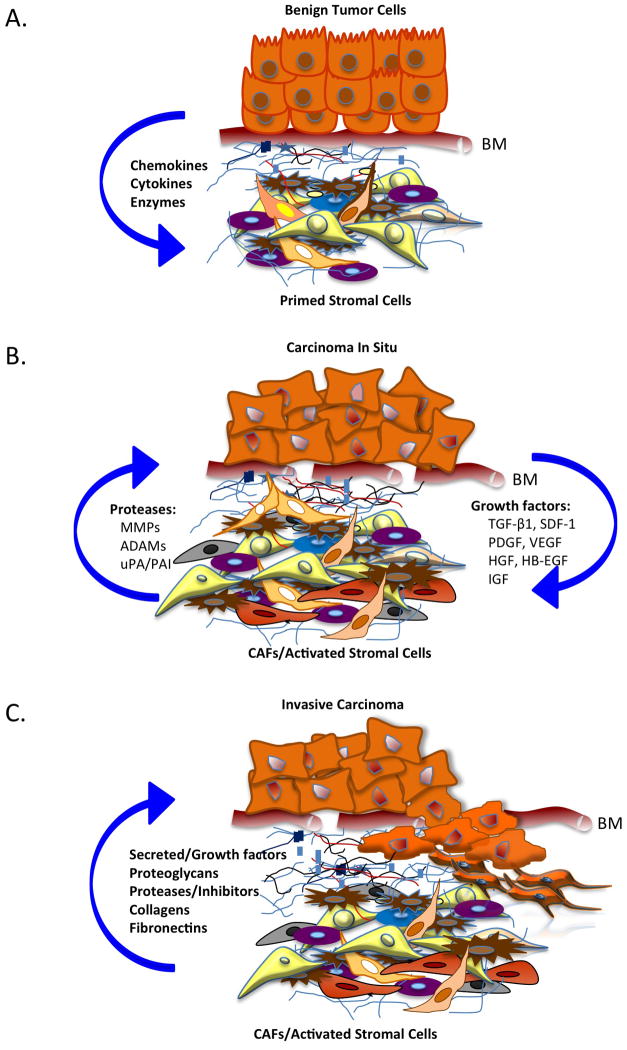

The extracellular matrix (ECM) has a major role in tumor development and progression. Over the last decade, it has become much clearer that reciprocal interactions between tumor and stromal cells determine the course of cancer progression. Although much remains to be understood about the chronology of events dictating tumor initiation and the context for reciprocal regulatory signals, it is clear that continuous bidirectional paracrine signaling establishes a microenvironment conducive for the survival of the tumor. Hence, in the study of the tumor stromal microenvironment, there are two sides to be examined: 1) the effects of tumor cell signaling on the surrounding stroma, and 2) the influence of paracrine stromal signals on tumor cells. In general, the reciprocal relationship supporting tumor progression might be viewed as follows: Tumor cells secrete cytokines, chemokines and enzymes that activate stromal cells and fibroblasts. Among a diverse group of molecules, these stromal cells secrete proteases that break down the tumor cell basement membrane. Consequently, growth factors are released from the underlying matrix, which not only initiate signaling pathways in tumor cells, but also activate fibroblasts further, inducing fibroblast secretion of a host of ECM factors responsible for regulating numerous, interrelated events. Tumor cells thrive in this convoluted but nourishing milieu, which ultimately promotes their survival, proliferation, and metastasis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reciprocal tumor:stromal cell signaling in the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor progression and stromal cell activation. A. Paracrine signals (soluble factors) from the tumor induce alterations that prime the stroma. B. Subsequent release of stromal proteases triggers breakdown of the tumor basement membrane (BM) and release of additional growth factors from tumor cells, further activating the stroma. C. Consequently, stromal cells secrete a myriad of factors such as growth factors, proteoglycans, proteases, and insoluble proteins to promote tumor growth, migration, and metastasis. During the process, cancer associate fibroblasts (CAFs) may be transformed.

Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have a profound role on ECM composition and dynamics. The ECM is composed of fibrillar and structural proteins, proteoglycans, integrins and proteases, all of which may be manufactured by CAFs. Hence, CAFs potentially can modulate levels and activities of all these factors. Indeed, various CAF-secreted soluble factors and proteolytic enzymes modulate the tumor microenvironment, altering composition of the connective tissue through remodeling. Because the ECM controls the availability and activation of growth factors and serves as a platform for integrin and growth factor receptors to regulate cell signaling pathways, fibroblasts modulate a multiplicity of growth factor-mediated pathways through changes in synthesis and changes in matrix components.

Growth Factors

Paracrine growth factors secreted by CAFs are central to the establishment of a microenvironment conducive to tumor growth and progression. Growth factors function at various stages through tumor progression, including proliferation, metastasis and dissemination. Such factors, particularly heparin-binding molecules, have the ability to induce a number of physiological events leading to tumor progression because of their diverse interactions with the ECM. In the ECM they may be sequestered or co-presented by other molecules, such as proteoglycans and various cell surface receptors, accounting for their biological diversity.

The prolific contributions of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) to cancer progression in the tumor microenvironment are linked largely to its role in recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells and myofibroblasts to the tumor, as SDF-1 is integral to CAF activation and the desmoplastic reaction. In addition to cancer cells, SDF-1 is largely secreted by CAFs and mesenchymal cells [1, 2] where it stimulates growth, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis and colonization in a number of cancers. It is noteworthy that bone marrow-derived CAFs secrete higher levels of SDF-1 than wild-type myofibroblasts [3], highlighting the particular importance of bone marrow-niche cells in cancer progression. SDF-1 is an important mediator of crosstalk between tumor cells and fibroblasts. Paracrine stromal SDF-1 signaling is stimulated in the presence of TGF-β1, which increases expression of epithelial CXCR4, resulting in SDF-1-mediated Akt activation and subsequent tumor progression and survival [4]. Additionally, SDF-1 promotes cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions by regulating integrin expression [5, 6].

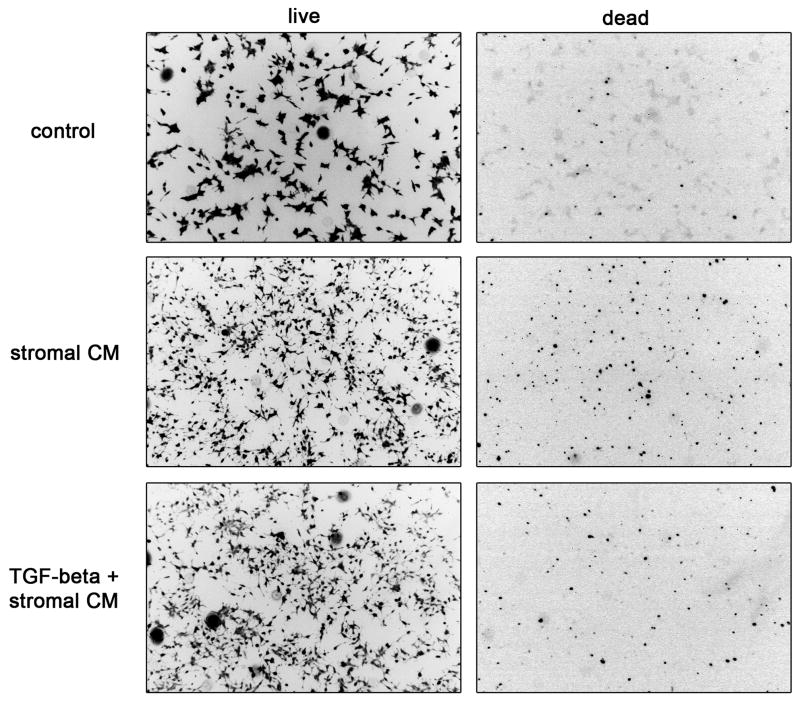

Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) plays a major role in activation of fibroblasts by promoting fibroblast to myofibroblast transdifferentiation. Further, TGF-β1 is actively secreted by CAFs and stromal cells. TGF-β1 is notoriously a complex, pleiotropic factor because of multiple binding partners and associated noncanonical signaling pathways. Consequently, it plays a role in both tumor suppression and tumor promotion. Although loss of TGF-β signaling through abrogation of TβRII in stroma has been shown to correlate with increased proliferation and progression of cancer cells [7–9], paracrine TGF-β1 signaling frequently induces metastasis and epithelial to mesenchymal transformation (EMT) of cancer cells. Such diverse actions of TGF-β appear to be dependent on contextual differences that include the tissue localization, cell source, extracellular mediators and the cell signaling context. We have found that while direct stimulation of prostate cancer cells with TGF-β1 suppresses growth and invasion [10], stimulation of bone marrow stromal cells with TGF-β1 suppresses paracrine apoptotic signals to promote prostate cancer cell survival (Figure 2). Similarly, overexpression of TGF-β1 in normal prostate fibroblasts induces invasive tumor growth [11]. Stromal TGF-beta is associated with tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer, and high stromal expression is correlated with increased mortality [12]. Additionally, orthotopic mammary carcinoma models have demonstrated a role for TGF-β in regulating tumor perfusion, as abrogation of TGF-β signaling in the stroma increases recruitment of perivascular cells, thus improving chemotherapeutic efficacy [13].

Figure 2.

TGF-beta pre-treatment of bone marrow stromal cells reverses stromal cell conditioned media (CM)-induced death of prostate cancer cells. HS-5 bone marrow stromal cells were pre-treated with or without TGF-β1 for 4 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Following PBS washes, fresh serum free medium was replaced and conditioned medium (CM) was collected after 48 hours incubation. C4-2 prostate cancer cells were treated with DMEM, HS-5 CM with vehicle, or HS-5 CM with exogenously added TGF-β1. A live/dead assay was performed using calcein AM and ethidium homodimer at a concentration of 125nM and 2μM, respectively to differentially label live cells from dead C4-2 cells. Representative images are shown from 5 fields per experiment run three times minimum. Color images, Green (calcein AM) and Red (Ethidium homodimer) were converted to grayscale and inverted in photoshop to produce black and white images. Images were captured using a Nikon 2000TE. Final magnification 25X.

TGF-β, among other factors, is an important regulator of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and the IGF axis, another very important signaling system in prostate cancer progression. In prostate stromal cells, TGF-β1 increases the expression of IGF-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) [14, 15], as well as the ratio of IGF-I bound to IGFBP-3, thereby decreasing growth of prostate cancer cells in co-culture [14]. Such regulation of IGF and binding protein levels provides one explanation for the divergent responses of TGF-β in prostate cancer. Prospective and case-control studies have found that elevated plasma IGF-1 predicts an increased prostate cancer risk several fold [16, 17], and elevated sera levels correlate with an increased risk for breast and colorectal cancer, although not statistically significant [18–20]. However, increased IGFBP-1 appears to be significantly associated with decreased risk for colorectal cancer (odds ratio, 0.48; 95% confidence interval, 0.23–1.00, p-value, 0.02) [21]. IGF-2 may also play a role in prostate and breast cancer, where it is expressed at higher levels by mammary stromal cells [22, 23], and in particularly large quantities by stromal cells in benign prostatic hyperplasia [24]. Although the prognostic significance of total stromal IGF-2 levels in breast cancer is inconclusive, patients with lower serum levels of free IGF-2 have larger malignant tumors [25]. Interestingly, the presence of integrin α11 on fibroblasts is associated with increased stromal IGF-2 levels in vivo in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), concomitant with an enhanced rate of tumor growth [26].

Similar to other heparin-binding growth factors, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), expressed by leukocytes and tumor cells, promotes angiogenesis likely through upregulating stromal production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [27], and may also have a more direct effect through stimulation of endothelial cells [28]. Although CAFs do not commonly express PDGF, they readily express PDGFR to promote angiogenesis and proliferation, which involves upregulation of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 and FGF-7 in cervical cancer [29, 30]. Inhibition of PDGF decreased stromal heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF)-mediated tumor cell growth in co-cultures of cervical cancer cells and CAFs from patient tumor tissues, highlighting the significance of PDGF in HB-EGF signaling, and cancer progression [31]. In addition to cervical CAFs, HB-EGF has been found to be expressed at high levels on prostate stromal cells [32, 33], where paracrine signals mediate prostate cancer survival and androgen independent tumor growth as well as neuroendocrine differentiation [34]. The effects of PDGF on cancer cell proliferation and progression occur largely through EGFR/ErbB signaling leading to activation of MAP kinase and PI3K/Akt. Similarly, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) activates RAS/MAPK and PI3K pathways in addition to many others, by binding c-MET, another receptor tyrosine kinase with a highly complex signaling profile [35]. CAF-secreted HGF promotes invasiveness of several cancers, including breast, colon, and oral squamous cell carcinoma [36–38]. Curiously, all HGF signaling in cancer cells may not be mediated through c-MET. Tate et al. clearly demonstrate a prostate cancer cell response to HGF in a c-MET-null background, thereby opening up the possibility of signaling through cell surface nucleolin [39]. Thus, heparin-binding growth factor-activated tyrosine kinases engage the extracellular matrix through focal adhesion complexes and associated downstream signaling cascades, ultimately inducing a variety of responses to promote tumorigenesis and cancer progression.

Collagen, Fibronectin, and Tenascin

CAFs secrete higher levels of collagens than those of normal tissue. It is well known that deposition of a dense collagen matrix is a major feature of the desmoplastic reaction. This generates a stiff collagen matrix, which is associated with increased activity of the matrix cross-linking enzyme lysyl-oxidase (LOX) [40]. Increased collagen density has been shown to promote proliferation of epithelial cells in three-dimensional matrices, and tumor formation of breast cancer cells, demonstrating the role of a collagen-dense environment in tumor initiation and progression. The consequence of enhanced collagen deposition is increased cell signaling pathways that promote cancer cell invasion, migration, and collagen reorganization. Isoform-specific expression of collagen may be dependent on tumor type and stage. Collagen I and III are upregulated commonly by CAFs or stromal cells in several cancers [41–45]. In gene expression studies, collagens X and XIα1 were increased in the reactive cancer stroma of invasive breast tumors, forming a prognostic signature [46, 47], although protein levels of collagen XIα1 were shown to be downregulated in malignant breast cancer in a separate analysis [48]. Upregulation of collagens IV, VI, XI, and XV, and downregulation of collagen XIV also has been observed in CAFs during the CAF-epithelial interaction in various cancers, in some cases forming a prognostic gene signature [49–52].

Carcinomas may be characterized by several variants of fibronectin or oncofetal fibronectin, which are present in the tumor stroma and expressed by myofibroblasts. Oncofetal isoforms including ED-A and ED-B fibronectin are derived by alternative splicing. Because of the varied specialized protein-binding domains, fibronectin isoforms may be unique in their affinity and specificity for ECM binding partners, which include fibrin, collagen, heparin, tenascin, syndecan and integrins. Oncofetal fibronectin is associated with an invasive phenotype, poor prognosis or poor differentiation in many cancers, as demonstrated in CAF:tumor spheroids as well as human tissues [53–56]. ED-B fibronectin is an angiogenic marker that is involved in neovascularization in advanced and remodeling tumors, and thus has a role in dissemination of cancer cells [57]. Migration stimulating factor (MSF), a truncated isoform of oncofetal fibronectin containing the gelatin-binding domain, also is secreted by both CAFs and oncofetal fibroblasts and induces migration [58]. The migratory response of fibroblasts to MSF is based on their ability to adhere to native collagen type I. Because of this MSF-induced migratory response, a microenvironment is established for the manifestation of an invasive phenotype in cancer cells [58]. Overexpression of MSF is correlated with poor survival of cancer patients [56].

The dynamic role of tenascin-C in the tumor microenvironment stems from its ability to interact with a diverse group of ECM molecules and surface receptors that initiate cell signaling pathways. Tenascin-C is resident in the stroma of many poorly differentiated tumors, expressed highly by fibroblasts [37, 59–61], and induced by a variety of signaling pathways. In earlier studies, It was proposed to be a stromal marker for mammary tumors because it was not detected in normal tissue [60], and also was found to be elevated in the sera of cancer patients [62]. Now, it is quite evident that tenascin-C has a prominent role in cancer – promoting angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation and metastasis, and increasing with tumor aggressiveness [61]. Recently it was identified as one among 11 analytes capable of differentiating between benign and malignant ovarian cancer [63]. In a mouse model of breast cancer, it was shown that secretion of tenascin-C by stromal cells expressing s100AF, a marker associated with metastasis and poor prognosis, promotes metastatic colonization of breast cancer [64]. Tenascin-C interacts with several integrins expressed on the surface of tumor cells and fibroblasts [65, 66]. It also binds fibronectin, and interferes with fibronectin-mediated adhesion, competing with the syndecan-4 binding site [67, 68]. Its anti-adhesive properties affect proliferation [68], and stimulate cancer cell migration by promoting disassembly of focal adhesions, thus interfering with integrin-mediated adhesions. Tenascin-C also was shown to inhibit activation of RhoA and associated stress fiber formation, and to induce filopodial extensions [69]. In particular, alternatively spliced fibronectin type III repeats are associated with increased motility and invasion [70]. Tenascin-W, although not as common as tenascin-C, has been shown to be a marker for activated tumor stroma, and is associated with increased migration of breast cancer cells [71]. Recently, it was found localized around the vasculature of tumor cells, and was shown to stimulate angiogenic activity in vitro [72]. Hence, Tenascin-W may have further utility as a marker for tumor angiogenesis.

Proteases

Proteolysis regulates and induces release of latent growth factors stored in the matrix, unveils protein domains, and generates bioactive fragments. Cleavage of the ECM by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and other proteases leads to activation of growth factors, as well as cytoskeletal reorganization and modification of downstream signaling pathways. Accordingly, VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) may be released and activated to promote angiogenesis [73, 74]. EGFR ligands, such as HB-EGF, also can be processed by MMPs [75], along with IGF-binding proteins [76, 77], which regulate the activity and bioavailability of IGF [78], along with ligand independent effects of IGF-BP fragments [79].

Numerous MMPs are expressed and secreted by CAFs, and enable cancer cells to evade tissue boundaries, escape the primary site, and metastasize. The significance of fibroblasts in synthesis of MMPs has become appreciated only recently, as MMP expression was assessed previously within the confines of the tumor. However, it is clearer now that stromal cells are the major source of MMPs, which become active at the invasive front [80]. Several co-culture models of tumor cells and fibroblasts have demonstrated enhanced activation of MMP-2 or expression of MT1-MMP, an activator of proMMP-2 (gelatinase) [81–83]. In vivo models also have shown the role of stromal MT1-MMP or MMP-2 in tumor cell growth [84, 85]. Notably, introduction of MMP-2-null fibroblasts reduced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) tumor volume in SCID mice by 90%, and abrogated invasion of collagen gels in co-culture. MMP-2 expression in CAFs has been highlighted as an indicator of poor prognosis for NSCLC [86]; and, in the prostate, MMP-2 is associated with an invasive phenotype [87, 88]. In the prostate, stromal MMP-2 levels are upregulated by TGF-β1 [89]. The significance of this may reside in the clinical observation that high serum TGF-β levels are associated with poor patient survival and increased bone metastasis [90, 91]. It has been suggested that proMMP2 is activated in CAFs as a consequence of collagen I binding of integrin β1. Interestingly, β1 integrin is activated by MT1-MMP-induced cleavage of the alpha V integrin precursor, promoting collagen binding and motility of cancer cells, thus providing a potential mechanism for MT1-MMP activation of MMP-2 [81, 92].

The unique set of MMPs expressed in the tumor stroma varies with tumor type and stage, and consequently, is context-dependent. Accordingly, in a squamous cell carcinoma model of benign and malignant HaCaT clones transplanted onto nude mice, expression of stromal-derived MMPs and their correlation with malignancy was examined, and stage-specific differences identified. mRNA of MMP-2, -9, -13, and -14 was upregulated in the stroma of malignant and invasive tumors, and MMP-3 was expressed exclusively in stroma representing very late stage disease [93]. During progression of breast cancer, MMP-9, -13, and -11 (stromelysin-3) are upregulated in reactive stroma, and have implications in invasion and osteolysis, with MMP-11 also being implicated in mammary tumor development [47, 94–97]. MMP-11 and -13 are associated with tumor progression, invasion, and poor prognosis in several other cancers [98–102], where they may be expressed by both stromal and tumor cells.

Other stromal-relevant MMPs are ADAM proteins, of which ADAM-17, -9, and -12 are expressed by myofibroblasts or stromal cells in colon cancer, liver metastases, and prostate cancer, respectively [103–105]. These ADAM proteins have a role in cancer development, progression, or invasion although the mechanisms have not been elucidated thoroughly. Production of ADAMTS-1 by fibroblasts is characteristic of many carcinomas and correlates with enhanced secretion of TGF-β1 and IL-1 β [106]. It was shown recently that fibroblasts in co-culture with breast cancer cells upregulate ADAMTS to promote invasion in an epigenetic mechanism, likely through decreased promoter-associated histone methylation[107]. Matrix metalloendopeptidase (CD10), is also expressed by CAFs, elevated in tumor stroma, and has prognostic value in NSCLC and breast cancer, although its precise role in cancer is still being examined [51, 108–111]. Among the MMP inhibitors, TIMP2 was shown to interfere with fibroblast-induced growth of cancer cells in a mouse model [112]. Interestingly, however, TIMP along with plasmin, may help to activate proMMP, and is released with MMP-2 [81, 113, 114]. TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 activity may be suppressed by Cathepsin B, which is localized to fibroblasts and correlated with invasion and shorter patient survival [115, 116].

Serine-proteases and their associated inhibitors are very significant in the continuous loop of proteolytic activities that ultimately promote tumor cell invasiveness. uPA system components pro-uPA, PAI-1 and PAI-2 are produced by fibroblasts and other stromal cells, and have an important role in tumor growth and metastasis. Whereas high levels of PAI-1 are associated with tumor progression, and poor prognosis - particularly for breast cancer [117, 118], increased PAI-2 has been correlated with better patient prognosis [119]. Although both PAI-1 and -2 inhibit uPA, an activator of plasmin, and hence prevent ECM degradation, PAI-1 and PAI-2 interact differently with members of the LDL receptor family. PAI-2 binds LDL receptors with lower affinity and consequently does not induce downstream signaling leading to cell proliferation, potentially explaining the observation of decreased metastasis associated with high PAI-2 levels in cancer [120].

Microarray studies have shown downregulation of the protease inhibitor and growth suppressor, WAP-type four-disulfide core (WFDC1), in CAFs [121–123]. Overexpression of WFDC1 inhibits proliferation of cancer cells, and WFDC1 expression was shown to decrease with progression of prostate cancer to metastatic disease [121]. The observation of downregulated WFDC1 in a diverse group of cancers highlights the potential prognostic significance of this molecule.

Proteoglycans

Like other ECM components in the convoluted tumor milieu, proteoglycans are implicated in many cell signaling pathways. This is due largely to their associated glycosaminoglycans, which bind and interact with a myriad of ECM proteins, macromolecules, cell adhesion molecules and growth factors. An important aspect of proteoglycan bioactivity is proteolytic cleavage or shedding. Ectodomain shedding affects the biological function of proteoglycans, altering proliferation, adhesion and migration responses. Additionally, proteolytic cleavage can yield anti-angiogenic peptide fragments to facilitate dissemination [124–126].

Syndecan-1 is expressed in the desmoplastic stroma or cancer fibroblasts of breast, ovarian, head and neck, and other carcinomas [127–131]. Its growth promoting ability has been demonstrated in 2D and 3D co-cultures, as well as knockout studies, particularly in breast cancer models. This growth-promoting function may be attributed to the cleaved, soluble form of syndecan-1 in some cancers [132], whereas the soluble ectodomain may be associated with decreased proliferation and increased invasiveness in breast and other cancers [133]. Of note, immunohistochemical examination showed that syndecan-1, which was redistributed from the epithelium to the stroma, was over 10-fold higher in aggressive breast tissue compared to normal tissue [134]. Similarly, fibroblast-secreted versican, promotes tumor growth, migration, and metastasis in breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer [135–139], and is a product of paracrine TGF-β1 signaling in the latter. Stromal versican is associated with relapse and poorer outcome in cancer patients [140–142]. Glypican-1 and -3 are additional proteoglycans that may have roles in tumor promotion, as they are overexpressed in a variety of carcinomas or associated stromal fibroblasts [128, 143–145].

On the other hand, decorin, expressed primarily by myofibroblasts, has a tumor-suppressive role, reducing tumor growth and metastasis in murine xenograft models, downregulating EGFR [146]. The decorin protein core, specifically, is tumor suppressive in triple negative breast cancer, inducing expression of stromal genes involved in cell adhesion and tumor suppression and suppressing genes involved in inflammation [147]. Decreased expression of decorin is a biomarker for aggressive soft tissue tumors [148]. Likewise, lumican, which is increased in the reactive stroma of primary tumors, was shown to inhibit invasion of metastatic prostate cancer cells in vitro [149].

Among the proteoglycans, perlecan is the most diverse in its bioactivities as a consequence of the multifunctional nature of its large protein core and heparan sulfate chains. Hence, it is not unexpected for the roles of perlecan to extend beyond development and normal biological processes into the tumor microenvironment [150]. Perlecan is present at high levels in the ECM and vascularized stroma of breast, colon, prostate and other cancers [151]. In metastatic melanomas, perlecan is increased up to 15-fold [152]. It contributes significantly to cancer cell proliferation, in part through cooperation with other growth factor pathways, such as FGF [153–155] and has additional domains that modulate angiogenic activity [156]. Its ability to activate FAK highlights potential involvement in other tumorigenic and pro-metastatic signaling pathways [157].

The highly prevalent pericellular glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan provides a hydration shelf to facilitate cell signaling and cancer progression. In addition to its receptor CD44, it interacts with proteoglycans and growth factor complexes to facilitate cell migration and metastasis. It has an important role in regulating inflammation, and can recruit tumor associated macrophages, which are necessary for extravasation [158]. Increased stromal hyaluronan expression is associated with poor prognosis and metastasis in breast, colon, prostate, ovarian, and lung cancer. It is clearly a vital player in the stromal tumor microenvironment [159–162].

Transmembrane proteins

Integrins, probably the most vital group of transmembrane proteins implicated in cancer progression, are integral components of the ECM, serving as liaisons for transmitting extracellular signals. Integrins bind RGD and other specificity sequences on fibronectin and tenascin, as well as proteoglycans, and growth factors. Integrin adhesions are regulated by proteases, and integrins reciprocally activate and regulate MMPs. Because integrins form attachments with the matrix and vasculature, they are imperative to tumor cell dissemination and extravasation from the primary site [163]. Integrin α11 is localized to mesenchymal cells, and was found overexpressed in NSCLC, where it was shown to have a role in tumorigenicity and increased expression of IGF-2 [26, 164]. This was demonstrated after implantation of integrin α11-deficient fibroblasts and NSCLC cells in SCID mice caused reduction of tumor volume, which was restored upon re-expression of α11 in knock-out mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Similarly, a population of CAFs from hepatocellular carcinoma liver tissue demonstrated significantly higher surface expression of integrin α4 and lower expression of α2 when compared to nonneoplastic tissue [165]. CAFs express several alpha subunits, including αV and α5, which interact with multiple beta subunits, and are capable of binding collagen, fibronectin, and soluble factors such as TGF-β1 [166–168]. Integrin ligands, ICAM and VCAM, have been shown to be upregulated and form a prognostic gene signature in CAFs [51, 52]. These molecules are significant largely because of their fundamental roles in connecting the ECM and cytoskeleton, initiating intracellular signaling pathways necessary for adhesion and motility (see discussion below on mechanical modeling).

Central to transmembrane proteins implicated in the fibroblastic tumor microenvironment is fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a serine protease with gelatinase activity expressed by stromal cells in various cancers [169]. It increases proliferation, adhesion and migration of ovarian cancer cells [170]. When expressed in breast cancer cells, it promoted tumor growth, increasing both the size and number of tumors [171, 172]. However, it is downregulated during the transformation of melanocytes, and may have a tumor suppressive role in melanoma [173, 174]. It is also elevated in kidney, gastric, basal cell, colon, and lung carcinoma [175–179]. Depletion of FAP expressing cells in the latter induced necrosis, and highlighted FAP as an immune-suppressor [178]. FAP interaction with integrin α3β1 may facilitate tumor cell adhesion and invasion [180].

Endosialin/TEM1 is a highly glycosylated integral membrane receptor expressed predominantly by CAFs, although initially characterized as a tumor endothelial marker [181, 182]. It has been demonstrated to bind ECM proteins such as fibronectin and collagen, and enhances cell adhesion and migration on these matrices. Additionally, it was shown to promote activation of MMP-9 [183]. In vivo experiments showed that deficiency of TEM1 decreased growth of lung carcinoma and fibrosarcoma [184]. Endosialin may be expressed by a subset of pericytes, and play a role in tumor angiogenesis, but this has not been elucidated fully [182].

Podoplanin is another integral transmembrane glycoprotein, involved in cell adhesion and the lymphatic vascular system. A receptor for selectins, it is recognized by the D2-40 monoclonal antibody, which has allowed for detection of this protein in lymph nodes. Podoplanin has been shown to be a very specific indicator for the detection of lymphatic invasion in primary tumors [185]. Podoplanin is expressed at higher levels in human vascular adventitial fibroblasts than lung-derived fibroblasts. Podoplanin-positive vascular fibroblasts demonstrated increased tumor formation, lymph node infiltration, and metastasis relative to podoplanin-negative vascular fibroblasts, underscoring the significance of podoplanin in metastasis [186]. Podoplanin has prognostic utility for several cancers. In breast cancer, podoplanin expression in CAFs correlated negatively with estrogen receptor status, and was associated with poor prognosis [187, 188]. Podoplanin expression in CAFs also is associated with poor prognosis in lung [189] and esophageal cancer [190], but interestingly, is a favorable prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer [191].

Protease-activated receptors (PARs) have an important role in tumor progression and metastasis of prostate cancer. PAR-1 is expressed mainly by myofibroblasts in the reactive stroma of primary prostate cancer tissues, while PAR-2 is expressed predominantly by prostate cancer cells. PAR-1 was found to be increased, particularly, in the stroma of high grade prostate cancers, and also was found in the endothelium and fibroblasts of the bone reactive stroma [192]. In the prostate, stromal PAR-1 may be upregulated by human glandular kallikrein-4 produced by prostate cancer cells, triggering secretion of interleukin-6 from stroma, in turn promoting cell proliferation, and upregulation of kallikreins in prostate cancer cells [193]. The activation and subsequent tumor-promoting effects of PAR-1 in the prostate tumor microenvironment provides a nice illustration of the significance of reciprocal tumor:stromal signals during cancer progression.

Secreted proteins

The secreted ECM glycoprotein osteonectin (ON) or Secreted Protein and Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC) is overexpressed in stromal or tumor cells of many cancers [194–197]. It was shown to increase microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinoma, and therefore may promote angiogenesis. It is highly prevalent in bone, and is a chemoattractant for bone-metastasizing cancers such as breast and prostate cancer [195]. Although it was anti-metastatic when overexpressed in breast cancer cells [198], stromal expression of ON along with CD10 was shown to be a prognostic indicator of recurrence for ductal carcinoma in situ [199]. Interestingly, stromal and tumor-derived ON was shown to suppress metastasis of bladder cancer in a murine syngeneic model. Co-cultures of bladder cancer and stromal cells demonstrated that ON suppressed the inflammatory phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages and CAFs by inhibiting reactive oxygen species formation via p38-JNK-AP1 and NFκB. Furthermore, absence of ON correlated with decreased expression of IL-6, SDF-1, VEGF, and TGF-β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in fibroblasts [200]. Consistent with a beneficial role for ON, overexpression of ON has been shown to increase susceptibility of ovarian and colon cancer to chemo- and radiation therapy [201, 202].

The related protein, osteopontin, is overexpressed in many cancers [203]. It is particularly abundant in the stroma of breast cancer, where it is associated with poor outcome, and skin fibroblasts, where it promotes preneoplastic and malignant tumor progression [204–206]. Similar to ON, osteopontin promotes prostate cancer growth and progression. The finding of higher osteopontin and ON expression in bone-metastasizing human prostate cancer tissue highlights the potential prognostic value of osteopontin and other bone-resident proteins in cancer [207, 208]. Osteopontin levels are also higher in triple-negative breast cancers [209]. Periostin is another secreted stromal protein overexpressed in many cancers including prostate, breast, colon, ovarian, pancreatic, and melanoma stroma. It is particularly important in the stromal reaction of cancer and functions at the tumor stromal interface [47, 210–213]. In the prostate, it correlates with poor prognosis, and is reportedly elevated 9-fold compared to BPH [47, 214]. Collectively, these proteins can bind collagen, fibronectin, tenascin, and many integrins, and therefore play a potentially significant role in matrix remodeling in the tumor microenvironment.

Biophysical and mechanical modeling of the ECM

The study of tumor-stromal interactions requires appropriate model systems. Much progress has been made with in vitro models, as the shift from two- to three-dimensional models have allowed for more physiologically relevant interactions –phenotypically and morphologically approximating the in vivo microenvironment. Spheroids have been used to examine these interactions [215], as well as other three-dimensional co-cultures using hydrogels and biologically relevant matrices [216–218], which are also useful in examining the mechanical aspects of the ECM and related tumor responses. Cells display distinct responses on matrix proteins and fibers, as a reflection of their physiological environment, emphasizing the importance of matrix selection in the study of the fibroblastic tumor microenvironment.

ECM tension and rigidity, which can be recapitulated in vitro with mechanical loading and occurs in vivo with enhanced matrix deposition and remodeling, influences stromagenesis [219], and tumor and fibroblast responses [220, 221]. In vitro studies have demonstrated that fibroblasts in three-dimensional or loaded collagen gels are stressed, and this is reflected in fibroblast phenotype and signaling events [222–224]. Mechanical force triggers transcription of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen to promote differentiation of myofibroblasts, with the latter requiring cooperation of TGF-β [225, 226]. These events are necessary for the invasion and proliferation of tumor cells [227, 228]. In a mechanical invasion assay utilizing paramagnetic micro beads within a collagen/fibronectin matrix and a rotating rare earth magnet, Menon et al. demonstrated that mechanical force applied to the matrix induced tumor cell invasion in a mechanism involving cofilin, and that fibronectin was required for this mechanosensory response [229]. Stretching of fibronectin induces mechanical stress resulting in initiation of various signaling pathways [220, 230]. The activation state of integrins is determined by mechanical influences, among other factors, and different integrin conformations bind to different surfaces of fibronectin. In the case of α5β1, this generates complexes of differential binding strengths, which ultimately will affect integrin-mediated signaling cascades [230–232], thus impacting tumor cell responses.

Mechanosensing integrins also respond to matrix rigidity or stiffness with enhanced signaling, activating FAK, ERK and RhoGTPase pathways [40, 233–235]. This is associated with increased contractility and migration in tumor cells, along with reorganization and stretching of the matrix. Examination of this response using breast cancer cells in a three-dimensional collagen gel demonstrated radial realignment of collagen fibers [236], a characteristic effect of migrating cells.

Additional studies examining the mechano-signaling pathways mediated by integrins will help elucidate mechanisms of tumor cell progression. Mechanical force also is associated with activity of tenascin-C, which can lead to enhanced invasiveness of tumor cells [237], as well as TGF-β, which has mechanoregulatory ability, stimulates matrix contraction, and is itself activated in response to stress [238–240]. Thus, it is the interconnected and dynamic network of external (mechanical) and intracellular signals that promotes cancer progression in the stromal tumor microenvironment.

Targeted Approaches

Experimental studies have generated quantitative information about ECM molecules relevant to the fibroblastic tumor microenvironment that ultimately must be translated into therapeutic targets or clinically useful prognostic indicators [241]. Mass screening has limitations, as it elucidates only transcribed genes, and may not be as sensitive as is necessary for accurate identification of therapeutic targets. Assessment of mRNA expression and protein levels frequently generates different results, and therefore, protein analysis should parallel gene expression studies when seeking therapeutic targets. Targeted inhibition of CAF-derived ECM proteins has proven difficult. For example, FAP was initially a very exciting target for reactive tumor stroma, but later studies with inhibitory antibodies reported no significant results [242]. However, other transmembrane proteins may prove to be useful biomarkers. Podoplanin in particular, shows promise as a marker of lymph node metastasis. This has obvious implications in cancer treatment and management, as there is an overwhelming need to distinguish metastatic cancers from organ-confined or locally invasive tumors. PAR-1, as well as α11β1 and endosialin have shown potential as therapeutic targets for prostate and lung cancer, respectively. Importantly, CAF-downregulated proteins, such as WFDC1 may be equally significant in the development of therapeutic modalities, and their utility should not be overlooked (Table 1). Inhibition of proteases has been challenging most likely because of their unique expression at different stages of progression, and varying regulatory functions in tumor and stromal cells. This elucidates the necessity of highly specific and strategic targeting of MMPs. Nonetheless, PAI-1 and -2 show encouraging prognostic utility particularly for breast cancer, which is supported by many studies.

Table 1.

Stromal Extracellular Matrix Factors and their Clinical Relevance/Prognostic Value in Cancer

| Factor | Expression | Clinical Significance | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncofetal fibronectin | stroma | malignancy, poor prognosis | oral (53), ovarian (54), colorectal (55), breast (56) |

| TGF-beta | stroma | mortality, tumor growth | prostate (11), breast (12) |

| SDF-1 | CAFs | tumor progression, angiogenesis | breast (1,2) |

| HB-EGF | stroma, CAFs | tumor growth | cervical (31), prostate (32) |

| Tenascin-C, -W | stroma | malignancy, metastasis | breast (60,64,71) |

| MMP-2 | stroma, sera | poor prognosis, metastasis invasion | NSCLC (86), prostate (88), skin SCC (93) |

| MMP-13 | myofibroblasts, stroma | poor prognosis, invasion | skin (93), HNSCC (99), colorectal (100), breast (102) |

| MMP-11 | fibroblasts, stroma | local invasiveness | breast (47), HNSCC (101) |

| Adam-9 | myofibroblasts | metastasis | colorectal (104) |

| Adam-12 | stroma | tumor progression | prostate (105) |

| PAI-1, uPA | tumor and stroma | poor prognosis | breast (117, 118) |

| PAI-2 | tumor and stroma | favorable prognosis | breast (117, 119) |

| WFDC-1 | CAFs (decreased) | metastasis | prostate (121) |

| Syndecan-1 | stroma | progression, poor survival | ovarian (128), endometrial (130), breast (134) |

| Versican | stroma | malignancy, progression | ovarian (141), prostate (142) |

| Decorin protein core | myofibroblasts | tumor suppression | triple-negative breast (147) |

| Hyaluronan | stroma | poor survival, metastasis | ovarian (159), breast (160), prostate (161), NSCLC (162) |

| ICAM | CAFs | progression | NSCLC (51) |

| VCAM | CAFs | metastasis | colorectal (52) |

| α11β1 | fibroblasts | tumorigenicity | NSCLC (26) |

| CD10 (MME) | CAFs, stroma | progression, poor prognosis, recurrence | NSCLC (51), melanoma (108), breast (109) |

| Podoplanin | CAFs |

|

breast (187,188), lung (189), esoph. (190), colorectal (191) |

| PAR-1 | stroma | progression | prostate (192) |

| Osteonectin (SPARC) | stroma |

|

breast (199), pancreatic (194) bladder (200) |

| Osteopontin | stroma | tumor progression | breast (204) |

| Periostin | stroma |

|

breast (47) prostate (47,214) |

Matrix proteins expressed at the target site may have prognostic significance when detected in the primary tumor tissue, as in the case of osteopontin and osteonectin. Because of their metastasis-promoting and chemoattractant properties, these proteins could be targeted specifically using competitive peptides to prevent colonization of tumor cells in bone. Bone stromal cells also display increased expression of the ECM proteins versican and tenascin, which promote tumor growth in three-dimensional coculture with advanced prostate cancer cells [243]. This provides further rationale for targeting tumor-promoting ECM proteins at the metastatic or secondary site, as it is presumable that cancer cells induce expression of ECM proteins in target tissue that contribute to their growth. Perlecan, with its diverse biological activities and contributions to tumor growth, is abundant in bone marrow, and may be another desired target for bone-metastasizing cancers [150, 244, 245]. Finally, given the role of proteases in tumor metastasis, fragments of many of these ECM molecules will likely prove to have significant biological effects quite varied from the native molecule. As such, these fragments may be either therapeutic targets or easily detected prognostic markers.

Summary

The reactive stroma is characterized by a diverse milieu of soluble and membrane-bound proteins mediating multiple deregulated biological processes. Reciprocal communication between tumor and stromal cells relies on signaling platforms regulated by the diverse components of the ECM, ultimately promoting tumor growth, survival and eventual colonization of the metastatic site. Thus, the ECM deserves special attention in the study of tumor development and progression and quest for therapeutic targets.

Expression of ECM components, and associated signaling events dictating cancer cell responses are determined by tumor stage and grade, as well as cancer type [47]. Therefore, these factors must be considered when attempting to understand the tumor stromal microenvironment. In the context of the continuous and intricate string of reciprocal signals in the tumor microenvironment, elucidation of relevant stromal components should parallel the discovery of tumor-secreted molecules induced by paracrine signaling.

Our knowledge of the functional significance of the ECM is based predominantly on standard two-dimensional bioassays and murine models, but it will take more innovative models carefully designed to recapitulate tumor-stromal interactions in three-dimensions in order to ascertain the clinicopathological relevance of specific matrix molecules. Hence, prospective studies of sufficient sample size – necessary first steps to uncover the true prognostic value of ECM proteins – must be proceeded by comprehensive studies in appropriate model systems to analyze and confirm the roles of these prospective targets. As the dynamics of tumor-stromal interactions at different tumor stages becomes clearer, targeted approaches to prevent and predict cancer progression can be introduced.

Implications

Tumor expansion and metastasis depend not only on the biology and signaling from or within the epithelial compartment of the cancer, but to a large degree on the paracrine factors and matrix composition of the cancer associated stroma. Future cancer therapy should target highly relevant stromal cell-derived matrix factors, consequently attenuating stromal-mediated paracrine signals associated with cancer progression.

Implications.

Cancer progression, even in epithelial cancers, may be based in large part in changes in signaling from cancer associated stromal cells. These changes may provide early prognostic indicators to further stratify patients during treatment or alter the timing of their follow up visits and observations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Translational Cancer Research, the Delaware INBRE program, NIH NIGMS (8 P20 GM103446-13) and NIH P01-CA98912 on Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis: Biology and Targeting.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121(3):335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tait LR, et al. Dynamic stromal-epithelial interactions during progression of MCF10DCIS. com xenografts. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(10):2127–34. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quante M, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ao M, et al. Cross-talk between paracrine-acting cytokine and chemokine pathways promotes malignancy in benign human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4244–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger M, et al. Functional expression of CXCR4 (CD184) on small-cell lung cancer cells mediates migration, integrin activation, and adhesion to stromal cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(50):8093–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann TN, et al. CXCR4 chemokine receptor and integrin signaling co-operate in mediating adhesion and chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells. Oncogene. 2005;24(27):4462–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhowmick NA, et al. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303(5659):848–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng N, et al. Loss of TGF-beta type II receptor in fibroblasts promotes mammary carcinoma growth and invasion through upregulation of TGF-alpha-, MSP- and HGF-mediated signaling networks. Oncogene. 2005;24(32):5053–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achyut BR, et al. Inflammation-mediated genetic and epigenetic alterations drive cancer development in the neighboring epithelium upon stromal abrogation of TGF-beta signaling. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles FL, et al. Increased TGF-beta1-mediated suppression of growth and motility in castrate-resistant prostate cancer cells is consistent with Smad2/3 signaling. Prostate. 2012;72(12):1339–50. doi: 10.1002/pros.22482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco OE, et al. Altered TGF-beta signaling in a subpopulation of human stromal cells promotes prostatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 71(4):1272–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardsen E, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of epithelial and stromal immunomodulatory signalling molecules is a prognostic indicator in breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:110. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, et al. TGF-beta blockade improves the distribution and efficacy of therapeutics in breast carcinoma by normalizing the tumor stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(41):16618–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117610109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawada M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 modulates tumor-stromal cell interactions of prostate cancer through insulin-like growth factor-I. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(2A):721–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massoner P, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) in the prostate and in prostate cancer: local production, distribution and secretion pattern indicate a role in stromal-epithelial interaction. Prostate. 2008;68(11):1165–78. doi: 10.1002/pros.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan JM, et al. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I and prostate cancer risk: a prospective study. Science. 1998;279(5350):563–6. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolk A, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and prostate cancer risk: a population-based, case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(12):911–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannucci E, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), IGF-binding protein-3 and the risk of colorectal adenoma and cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2000;10(Suppl A):S30–1. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(00)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarty MF. Androgenic progestins amplify the breast cancer risk associated with hormone replacement therapy by boosting IGF-I activity. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56(2):213–6. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinaldi S, et al. IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk in women: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(2):593–605. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaaks R, et al. Serum C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF-binding proteins, and colorectal cancer risk in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(19):1592–600. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giani C, et al. Stromal IGF-II messenger RNA in breast cancer: relationship with progesterone receptor expressed by malignant epithelial cells. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21(3):160–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03347295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen AA, Cullen KJ. Paracrine/autocrine regulation of breast cancer by the insulin-like growth factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;47(3):219–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1005903000777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen P, et al. Insulin-like growth factor axis abnormalities in prostatic stromal cells from patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(5):1410–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7525636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer CF, et al. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-II serum concentrations in patients with benign and malignant breast lesions: free IGF-II is correlated with breast cancer size. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(12 Pt 1):4003–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu CQ, et al. Integrin alpha 11 regulates IGF2 expression in fibroblasts to enhance tumorigenicity of human non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(28):11754–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703040104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y. Direct role of PDGF-BB in lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(2):228–30. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.2.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao R, et al. PDGF-BB induces intratumoral lymphangiogenesis and promotes lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):333–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain RK, Lahdenranta J, Fukumura D. Targeting PDGF signaling in carcinoma-associated fibroblasts controls cervical cancer in mouse model. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietras K, et al. Functions of paracrine PDGF signaling in the proangiogenic tumor stroma revealed by pharmacological targeting. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murata T, et al. HB-EGF and PDGF mediate reciprocal interactions of carcinoma cells with cancer-associated fibroblasts to support progression of uterine cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71(21):6633–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adam RM, et al. Amphiregulin is coordinately expressed with heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in the interstitial smooth muscle of the human prostate. Endocrinology. 1999;140(12):5866–75. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman MR, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in the human prostate: synthesis predominantly by interstitial and vascular smooth muscle cells and action as a carcinoma cell mitogen. J Cell Biochem. 1998;68(3):328–38. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19980301)68:3<328::aid-jcb4>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adam RM, et al. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor stimulates androgen-independent prostate tumor growth and antagonizes androgen receptor function. Endocrinology. 2002;143(12):4599–608. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comoglio PM, Giordano S, Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(6):504–16. doi: 10.1038/nrd2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daly AJ, McIlreavey L, Irwin CR. Regulation of HGF and SDF-1 expression by oral fibroblasts--implications for invasion of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(7):646–51. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Wever O, et al. Tenascin-C and SF/HGF produced by myofibroblasts in vitro provide convergent pro-invasive signals to human colon cancer cells through RhoA and Rac. FASEB J. 2004;18(9):1016–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1110fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jedeszko C, et al. Fibroblast hepatocyte growth factor promotes invasion of human mammary ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):9148–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tate A, et al. Met-Independent Hepatocyte Growth Factor-mediated regulation of cell adhesion in human prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levental KR, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139(5):891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crispino P, et al. Role of desmoplasia in recurrence of stage II colorectal cancer within five years after surgery and therapeutic implication. Cancer Invest. 2008;26(4):419–25. doi: 10.1080/07357900701788155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faouzi S, et al. Myofibroblasts are responsible for collagen synthesis in the stroma of human hepatocellular carcinoma: an in vivo and in vitro study. J Hepatol. 1999;30(2):275–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huijbers IJ, et al. A role for fibrillar collagen deposition and the collagen internalization receptor endo180 in glioma invasion. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kauppila S, et al. Aberrant type I and type III collagen gene expression in human breast cancer in vivo. J Pathol. 1998;186(3):262–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(1998110)186:3<262::AID-PATH191>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuxhorn JA, et al. Reactive stroma in human prostate cancer: induction of myofibroblast phenotype and extracellular matrix remodeling. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(9):2912–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer M, et al. Heterogeneity of gene expression in stromal fibroblasts of human breast carcinomas and normal breast. Oncogene. 2010;29(12):1732–40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Planche A, et al. Identification of prognostic molecular features in the reactive stroma of human breast and prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e18640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halsted KC, et al. Collagen alpha1(XI) in normal and malignant breast tissue. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(10):1246–54. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allinen M, et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukushima N, et al. Characterization of gene expression in mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas using oligonucleotide microarrays. Oncogene. 2004;23(56):9042–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Navab R, et al. Prognostic gene-expression signature of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts in non-small cell lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(17):7160–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014506108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakagawa H, et al. Role of cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts in metastatic colon cancer to the liver and their expression profiles. Oncogene. 2004;23(44):7366–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mandel U, et al. Oncofetal fibronectins in oral carcinomas: correlation of two different types. APMIS. 1994;102(9):695–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menzin AW, et al. Identification of oncofetal fibronectin in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: detection in ascitic fluid and localization to primary sites and metastatic implants. Cancer. 1998;82(1):152–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980101)82:1<152::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inufusa H, et al. Localization of oncofetal and normal fibronectin in colorectal cancer. Correlation with histologic grade, liver metastasis, and prognosis. Cancer. 1995;75(12):2802–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2802::aid-cncr2820751204>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schor AM, Schor SL. Multiple Fibroblast Phenotypes in Cancer Patients:Heterogeneity in Expression of Migration Stimulating Factor. In: Mueller MM, Fusenig F, editors. Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts and Their Matrix: Tumor Stroma. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santimaria M, et al. Immunoscintigraphic detection of the ED-B domain of fibronectin, a marker of angiogenesis, in patients with cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(2):571–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schor SL, et al. Migration-stimulating factor: a genetically truncated onco-fetal fibronectin isoform expressed by carcinoma and tumor-associated stromal cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63(24):8827–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lightner VA, Slemp CA, Erickson HP. Localization and quantitation of hexabrachion (tenascin) in skin, embryonic brain, tumors, and plasma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;580:260–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mackie EJ, et al. Tenascin is a stromal marker for epithelial malignancy in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(13):4621–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brellier F, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. How do tenascins influence the birth and life of a malignant cell? J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schenk S, et al. Tenascin-C in serum: a questionable tumor marker. Int J Cancer. 1995;61(4):443–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amonkar SD, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a multivariate index assay for ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Connell JT, et al. VEGF-A and Tenascin-C produced by S100A4+ stromal cells are important for metastatic colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(38):16002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yokosaki Y, et al. Differential effects of the integrins alpha9beta1, alphavbeta3, and alphavbeta6 on cell proliferative responses to tenascin. Roles of the beta subunit extracellular and cytoplasmic domains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(39):24144–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yokosaki Y, et al. The integrin alpha 9 beta 1 mediates cell attachment to a non-RGD site in the third fibronectin type III repeat of tenascin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(43):26691–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang W, et al. Interference of tenascin-C with syndecan-4 binding to fibronectin blocks cell adhesion and stimulates tumor cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2001;61(23):8586–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orend G, et al. Tenascin-C blocks cell-cycle progression of anchorage-dependent fibroblasts on fibronectin through inhibition of syndecan-4. Oncogene. 2003;22(25):3917–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wenk MB, Midwood KS, Schwarzbauer JE. Tenascin-C suppresses Rho activation. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(4):913–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hancox RA, et al. Tumour-associated tenascin-C isoforms promote breast cancer cell invasion and growth by matrix metalloproteinase-dependent and independent mechanisms. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(2):R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scherberich A, et al. Tenascin-W is found in malignant mammary tumors, promotes alpha8 integrin-dependent motility and requires p38MAPK activity for BMP-2 and TNF-alpha induced expression in vitro. Oncogene. 2005;24(9):1525–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martina E, et al. Tenascin-W is a specific marker of glioma-associated blood vessels and stimulates angiogenesis in vitro. FASEB J. 2010;24(3):778–87. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-140491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lederle W, et al. MMP13 as a stromal mediator in controlling persistent angiogenesis in skin carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(7):1175–84. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whitelock JM, et al. The degradation of human endothelial cell-derived perlecan and release of bound basic fibroblast growth factor by stromelysin, collagenase, plasmin, and heparanases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(17):10079–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suzuki M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 releases active heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor by cleavage at a specific juxtamembrane site. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(50):31730–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fowlkes JL, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases degrade insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in dermal fibroblast cultures. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(41):25742–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thrailkill KM, et al. Characterization of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5-degrading proteases produced throughout murine osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 1995;136(8):3527–33. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7543045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Degraff DJ, Aguiar AA, Sikes RA. Disease evidence for IGFBP-2 as a key player in prostate cancer progression and development of osteosclerotic lesions. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1(2):115–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gregory CW, Degeorges A, Sikes RA. The role of the IGF axis in the development and progression of prostate cancer. In: Pandalai SG, Mukhtar H, Labrie F, editors. Recent Research Developments in Cancer. Transworld Research Network; Kerala, India: 2001. pp. 437–462. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nelson AR, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: biologic activity and clinical implications. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(5):1135–49. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Boyd RS, Balkwill FR. MMP-2 release and activation in ovarian carcinoma: the role of fibroblasts. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(3–4):315–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ko K, et al. Activation of fibroblast-derived matrix metalloproteinase-2 by colon-cancer cells in non-contact Co-cultures. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(2):165–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tokumaru Y, et al. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: studies of clinical samples and in vitro cell lines co-cultured with fibroblasts. Cancer Lett. 2000;150(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taniwaki K, et al. Stroma-derived matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 promotes membrane type 1-MMP-dependent tumor growth in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4311–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang W, et al. Fibroblast-derived MT1-MMP promotes tumor progression in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ishikawa S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 status in stromal fibroblasts, not in tumor cells, is a significant prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(19):6579–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Giannoni E, et al. Reciprocal activation of prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Cancer Res. 2010;70(17):6945–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gohji K, et al. Serum matrix metalloproteinase-2 and its density in men with prostate cancer as a new predictor of disease extension. Int J Cancer. 1998;79(1):96–101. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980220)79:1<96::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu L, et al. Estrogens promote invasion of prostate cancer cells in a paracrine manner through up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in prostatic stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2011;152(3):773–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shariat SF, et al. Preoperative plasma levels of transforming growth factor beta(1) (TGF-beta(1)) strongly predict progression in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2856–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wikstrom P, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 is associated with angiogenesis, metastasis, and poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer. Prostate. 1998;37(1):19–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980915)37:1<19::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Baciu PC, et al. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) processing of pro-alphav integrin regulates cross-talk between alphavbeta3 and alpha2beta1 integrins in breast carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291(1):167–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vosseler S, et al. Distinct progression-associated expression of tumor and stromal MMPs in HaCaT skin SCCs correlates with onset of invasion. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(10):2296–306. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nielsen BS, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 is induced in fibroblasts in polyomavirus middle T antigen-driven mammary carcinoma without influencing tumor progression. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang TN, Albo D, Tuszynski GP. Fibroblasts promote breast cancer cell invasion by upregulating tumor matrix metalloproteinase-9 production. Surgery. 2002;132(2):220–5. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.125353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Masson R, et al. In vivo evidence that the stromelysin-3 metalloproteinase contributes in a paracrine manner to epithelial cell malignancy. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(6):1535–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Andarawewa KL, et al. Dual stromelysin-3 function during natural mouse mammary tumor virus-ras tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5844–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boulay A, et al. High cancer cell death in syngeneic tumors developed in host mice deficient for the stromelysin-3 matrix metalloproteinase. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):2189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Culhaci N, et al. Elevated expression of MMP-13 and TIMP-1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas may reflect increased tumor invasiveness. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leeman MF, McKay JA, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 activity is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(10):758–62. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.10.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Muller D, et al. Increased stromelysin 3 gene expression is associated with increased local invasiveness in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53(1):165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nielsen BS, et al. Collagenase-3 expression in breast myofibroblasts as a molecular marker of transition of ductal carcinoma in situ lesions to invasive ductal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61(19):7091–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Blanchot-Jossic F, et al. Up-regulated expression of ADAM17 in human colon carcinoma: co-expression with EGFR in neoplastic and endothelial cells. J Pathol. 2005;207(2):156–63. doi: 10.1002/path.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mazzocca A, et al. A secreted form of ADAM9 promotes carcinoma invasion through tumor-stromal interactions. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4728–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Peduto L, et al. ADAM12 is highly expressed in carcinoma-associated stroma and is required for mouse prostate tumor progression. Oncogene. 2006;25(39):5462–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rocks N, et al. Emerging roles of ADAM and ADAMTS metalloproteinases in cancer. Biochimie. 2008;90(2):369–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tyan SW, et al. Breast cancer cells induce stromal fibroblasts to secrete ADAMTS1 for cancer invasion through an epigenetic change. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bilalovic N, et al. CD10 protein expression in tumor and stromal cells of malignant melanoma is associated with tumor progression. Mod Pathol. 2004;17(10):1251–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Makretsov NA, et al. Stromal CD10 expression in invasive breast carcinoma correlates with poor prognosis, estrogen receptor negativity, and high grade. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(1):84–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dall’Era MA, et al. Differential expression of CD10 in prostate cancer and its clinical implication. BMC Urol. 2007;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cui L, et al. Prospectively isolated cancer-associated CD10(+) fibroblasts have stronger interactions with CD133(+) colon cancer cells than with CD133(-) cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Noel A, et al. Inhibition of stromal matrix metalloproteases: effects on breast-tumor promotion by fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 1998;76(2):267–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980413)76:2<267::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kitamura H, et al. Basement membrane patterns, gelatinase A and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 expressions, and stromal fibrosis during the development of peripheral lung adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(3):331–8. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ra HJ, Parks WC. Control of matrix metalloproteinase catalytic activity. Matrix Biol. 2007;26(8):587–96. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Graf M, Baici A, Strauli P. Histochemical localization of cathepsin B at the invasion front of the rabbit V2 carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1981;45(6):587–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Campo E, et al. Cathepsin B expression in colorectal carcinomas correlates with tumor progression and shortened patient survival. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(2):301–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Foekens JA, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its inhibitor PAI-1: predictors of poor response to tamoxifen therapy in recurrent breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(10):751–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Look MP, et al. Pooled analysis of prognostic impact of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its inhibitor PAI-1 in 8377 breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(2):116–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Duggan C, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(5):622–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Croucher DR, et al. Revisiting the biological roles of PAI2 (SERPINB2) in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(7):535–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Madar S, et al. Modulated expression of WFDC1 during carcinogenesis and cellular senescence. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(1):20–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sanchez-Carbayo M, et al. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(5):778–89. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wachi S, Yoneda K, Wu R. Interactome-transcriptome analysis reveals the high centrality of genes differentially expressed in lung cancer tissues. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(23):4205–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Endo K, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 stimulates cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(42):40764–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-4 by ADAMTS1 provokes defects in adhesion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(4):800–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Iozzo RV, Zoeller JJ, Nystrom A. Basement membrane proteoglycans: modulators Par Excellence of cancer growth and angiogenesis. Mol Cells. 2009;27(5):503–13. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Maeda T, Alexander CM, Friedl A. Induction of syndecan-1 expression in stromal fibroblasts promotes proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(2):612–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]