Abstract

This Letter describes a novel series of GIRK activators identified through an HTS campaign. The HTS lead was a potent and efficacious dual GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 activator. Further chemical optimization through both iterative parallel synthesis and fragment library efforts identified dual GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 activators as well as the first examples of selective GIRK1/4 activators. Importantly, these compounds were inactive on GIRK2 and other non-GIRK1 containing GIRK channels, and SAR proved shallow.

Keywords: GIRK, Kir3.x, Activators, Thallium flux

The G protein regulated Inwardly Rectifying Potassium (K+) (GIRK) channels are a family of inward-rectifying potassium channels also known as the Kir3 family, whose physiological role is to modulate the excitability of the various cell types in which they are expressed.1-4 Four GIRK channel subunits are expressed, as either homo- or heterodimers, in mammals: GIRK1 (Kir3.1), GIRK2 (Kir3.2), GIRK3 (Kir3.3) and GIRK4 (Kir3.4). GIRK1–GIRK3 are the predominant subunits in the CNS, with GIRK4 expressed at low levels.1-7 Multiple lines of evidence support important roles for GIRK in a variety of physiological processes including the control of heart rate and electrical excitability in a variety of neuronal populations, leading to postulates that GIRK channel modulation as potential target for a variety of therapeutic indications including pain, epilepsy, and reward/addiction.1-7 However, a complete lack of selective and effective GIRK activators has prevented further target validation for the many indications where GIRK activation is speculated to be of potential benefit.1-7 Indeed, the only compounds that are known to activate GIRK are alcohols (e.g., ethanol) at concentrations of hundreds of millimolar and, recently, the compound naringin has been identified as a GIRK activator; however, the reported EC50 is in excess of 100 μM.7-9

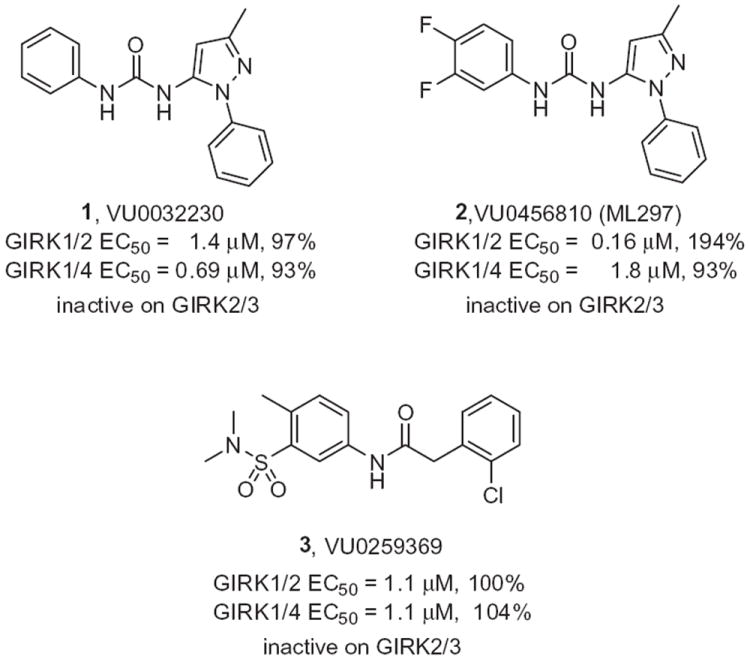

Based on this limitation in the field, we elected to develop a suite of small molecule GIRK probes. Towards this goal, we identified GIRK activator leads by mining HTS hits obtained from an MLSCN10 mGlu8 screening project, where mGlu8 activity was measured via a thallium flux-based readout of GIRK1/GIRK2.11 Once hits for mGlu8 (mGlu8/Gqi9 calcium flux assay) were triaged, multiple hits remained that were putative GIRK activators with potencies ranging from ~1 μM to 10 μM. We recently reported on the one series (Fig. 1) from this effort, represented by HTS hit 1 (VU0032230), that was subsequently optimized to afford the first selective (~10-fold vs GIRK1/4, inactive on GIRK2/3 and inactive on othe K+ channels) GIRK1/2 activator 2 (VU0456810, also known as ML297).12 Importantly, 2 was centrally penetrant and established anti-epileptic properties in mice via GIRK1/2 acitvation. The HTS also identified another attractive, and structurally distinct, dual GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 activator 3 (VU0259369), and in this letter, we detail the synthetic strategy and SAR for this lead.

Figure 1.

Structures and GIRK activities of HTS leads 1 and 3, and the optimized GIRK1/2 activator 2.

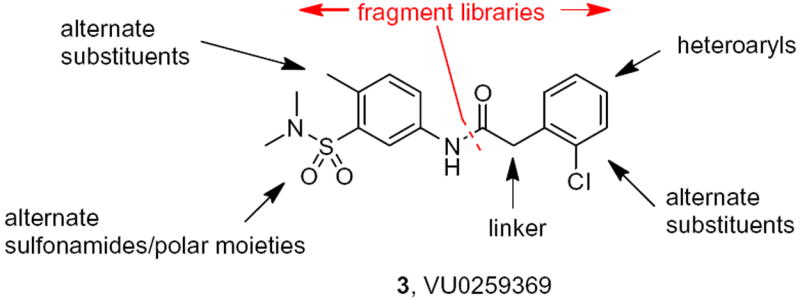

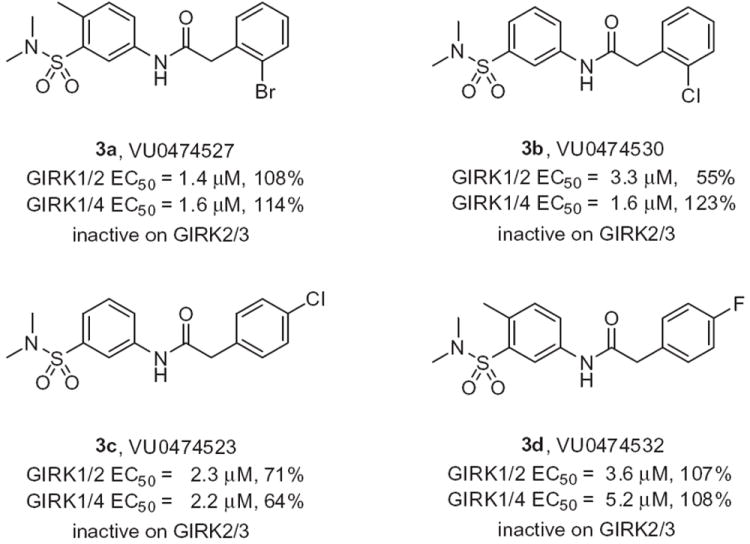

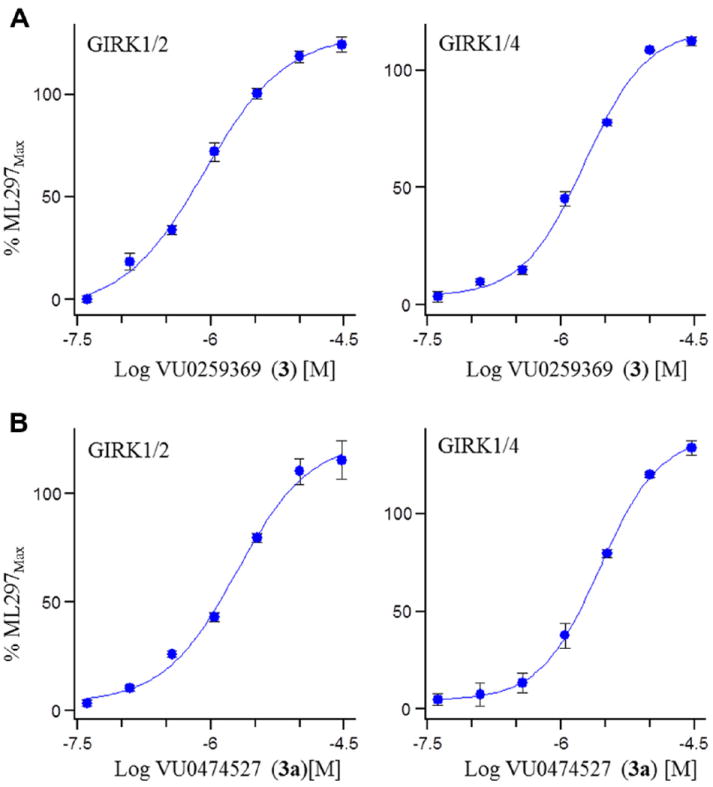

The optimization strategy for 3 is shown in Figure 2. Here, we elected to pursue divergent approaches in parallel, that consisted of iterative parallel library synthesis and a fragment library approach, to enable both the optimization as well as an attempt to identify a minimum pharmacophore.13,14 In short order, over 100 analogs were synthesized (via standard acylation chemistry) and assayed in the GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 thallium flux assays, and SAR proved to be shallow for this series, with >50% of the analogs displaying no GIRK activity. The itertaive parallel synthesis effort, surveying modifications to the parent 3, afforded few actives (Fig. 3). Of the actives, bromine effectively replaced the chlorine atom, as in 3a, in contrast deletion of the methyl group, providing 3b, maintained potency and efficacy at GIRK1/4, but diminished potency and lost efficacy at GIRK1/2. Moving the halogen of 3 from the 2- to the 4-position, as in 3c and 3d, also led to a diminution in potency at both GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4. Figure 4 highlights the GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 concentration response curves for 3 and 3a. All attempts to replace or modify the N,N-dimethyl sulfonamide group, incorporation of heterocycles or modification of the linker moiety led to a complete loss of GIRK activity. Fortunately, the fragment libraries proved more productive.

Figure 2.

Chemical optimization plan for 3, consisting of iterative parallel synthesis and fragment libraries.

Figure 3.

Representative active GIRK activators from iterative parallel synthesis effort around 3.

Figure 4.

GIRK activator concentration response curves (CRC) measuring thallium flux. (A) GIRK1/2 (EC50 = 1.1 μM, 110%) and GIRK1/4 (EC50 = 1.1 μM, 104%) CRCs for the HTS hit 3; (B) GIRK1/2 (EC50 = 1.4 μM, 108%) and GIRK1/4 (EC50 = 1.6 μM, 114%) CRC for related analog 3a.11

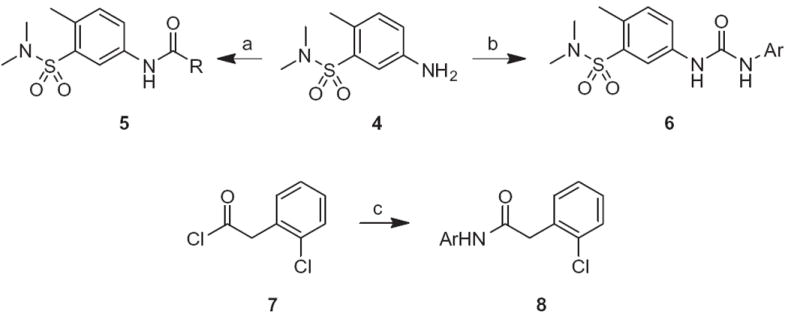

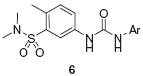

For the fragment libraries (Fig. 2), we held the 5-(N,N-dimethyl-sulfonamide)-4-methylphenyl moeity 4 constant, and prepared libraries of amide 5 and urea congeners 6 (Scheme 1). In parallel, we held the 2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetamide portion constant, and treated the acid chloride 7 with a variety of anilines to provide analogs 8. Yields for these libraries ranged from 22% to 95% based on the coupling partners employed.15

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) RCOCl, TEA, DMF, rt, 16 h, 45–95%; (b) RNCO, DMF, rt, 22–88%; (c) ArNH2, TEA, DMF, rt, 37–92%.

The amide congeners 5 proved to be uniformly inactive, with the exception of a few C4- to C8-aliphatic amide congeners; however, the GIRK1/2 EC50s were in the 4–10 μM range with modest efficacies (23–91%). In contrast, the urea congeners 6 possessed robust SAR, low micromolar potencies, high efficacy (71–120%) and engendered a slight preference for GIRK1/2 (Table 1). This effort provided dual GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 activators such as 6b, 6f and 6j, with a range of full to partial efficacies. This is an important finding, as it is not yet clear if a full or partial GIRK activator will be more ideal in terms of in vivo efficacy, safety and tolerability, and having a range of chemical tools will enable these issues to be addressed. Analogs such as 6h, with a 4-CF3 moiety, proved to be selective for GIRK1/2 (EC50 = 1.5 μM) over GIRK1/4 (EC50 >10 μM), but with low efficacy (26%). Electron rich congeners, such as 6i, were uniformly inactive at both GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4.

Table 1.

Structures and GIRK activities of analogs 6

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | Ar | GIRK1/2

|

GIRK1/4

|

||

| EC50a (μM) | Efficacya (%) | EC50a (μM) | Efficacya (%) | ||

| 6a | Ph | 1.4 | 94 | 3.9 | 100 |

| 6b | 4-ClPh | 3.3 | 92 | 2.8 | 72 |

| 6c | 3-Cl,4-MePh | 2.9 | 91 | 6.2 | 115 |

| 6d | 4-OMePh | 1.7 | 101 | 5.6 | 104 |

| 6e | 2-FPh | 3.9 | 111 | 7.8 | 72 |

| 6f | 3-FPh | 1.1 | 89 | 1.8 | 55 |

| 6g | 2-ClPh | 2.7 | 94 | 6.8 | 106 |

| 6h | 4-CF3Ph | 1.5 | 26 | >10 | ND |

| 6i | 2,5-diOMePh | >10 | ND | >10 | ND |

| 6j | 3-CNPh | 3.9 | 83 | 3.3 | 29 |

Potency values were obtained from triplicate determinations and the reported efficacy values shown are standardized to the efficacy of 2, arbitrarily designated to 100%.

ND = not determined.

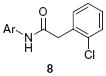

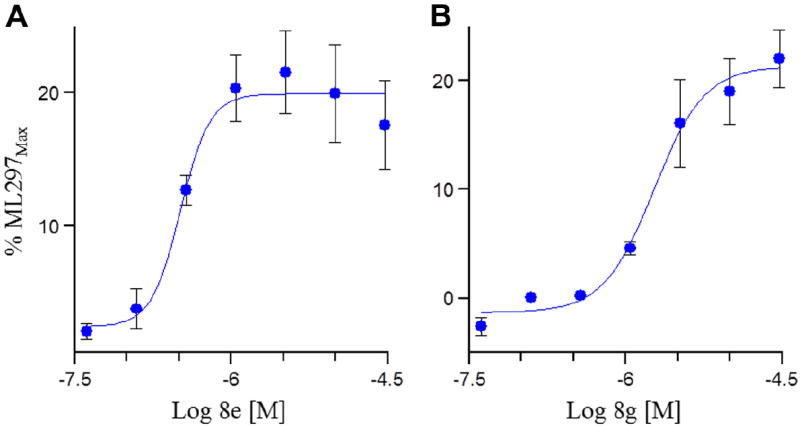

In analogs 8, where the eastern 2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetamide portion was held constant and diverse anilines were surveyed, interesting SAR emerged (Table 2). SAR was very shallow, and unlike analogs 6, all analogs 8 were devoid of activity at GIRK1/2, affording GIRK1/4 preferring activators. A 4-Cl,3-CF3phenyl amide derivative 8e, was a very potent GIRK1/4 activator (EC50 = 0.24 - μM), but displayed weak, partial activation (17%) of the channel, and was inactive on GIRK1/2. Other electron withdrawing substituents in the 3-position, such as Cl (8g) or CF3 (8h), were selective, partial GIRK1/4 activators; interestingly, electron donating substiuents in the 3-position, such as 8i, were inactive at both GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4. None of the analogs 6 or 8 were active at non-GIRK1 containing GIRK channels, further enabling them as valuable tool compounds to better understand selective GIRK channel activation (see Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Structures and GIRK activities of analogs 8

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | Ar | GIRK1/2

|

GIRK1/4

|

||

| EC50a (μM) | Efficacya (%) | EC50a (μM) | Efficacya (%) | ||

| 8a | 4-F,3-SO2MePh | >10 | ND | >10 | ND |

| 8b | 3-t-BuPh | 5.9 | 44 | 2.7 | 76 |

| 8c | 3-OCHF2Ph | >10 | ND | 7.8 | 119 |

| 8d | 3-Cl,5-CF3Ph | >10 | ND | >10 | ND |

| 8e | 4-Cl,3-CF3Ph | >10 | ND | 0.24 | 17 |

| 8f | 4-ClPh | >10 | ND | >10 | ND |

| 8g | 3-ClPh | >10 | ND | 1.8 | 22 |

| 8h | 4-CF3Ph | >10 | ND | 2.1 | 20 |

| 8i | 3-MePh | >10 | ND | >10 | ND |

Potency values were obtained from triplicate determinations and the reported efficacy values shown are standardized to the efficacy of 2, arbitrarily designated to 100%.

ND = not determined.

Figure 5.

GIRK activator concentration response curves (CRC) measuring thallium flux. (A) GIRK1/4 (EC50 = 0.24 μM, 17%) CRC for 8e; (B) GIRK1/4 (EC50 = 1.8 μM, 22%) CRCs for 8g.11

In summary, we have described the synthesis and one of the first accounts of SAR for a novel series of rarely described GIRK activators, indicating that GIRK activators can be identified from HTS campaigns and optimized. SAR proved shallow, and an iterative parallel synthesis approach provided little improvement in terms of potency or efficacy at GIRK1/2 or GIRK1/4. Instead a fragment library approach afforded a diverse array of GIRK activators that included dual GIRK1/2 and GIRK1/4 activators, GIRK1/2 preferring activators and GIRK1/4 selective activators possessing a wide range of efficacy (from weak partial to full activation), and devoid of activity at non-GIRK1-containing GIRK channels. Additional characterization and refinements are in progress and will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

Vanderbilt is a member of the MLPCN and houses the Vanderbilt Specialized Chemistry Center for Accelerated Probe Development. This work was supported by the NIH/MLPCN grant U54 MH084659 (C.W.L.), the Vanderbilt Department of Pharmacology and William K. Warren, Jr. who funded the William K. Warren, Jr. Chair in Medicine (to C.W.L.). Funding for the NMR instrumentation was provided in part by a grant from NIH (S10 RR019022).

References and notes

- 1.Kubo Y, Reuveny E, Slesinger PA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Nature. 1993;364:802. doi: 10.1038/364802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesage F, Duprat F, Fink M, Guillemare E, Coppola T, Lazdunski M, Hugnot JP. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:37. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi T, Ikeda K, Ichikawa T, Abe S, Togashi S, Kumanishi T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;208:1166. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karschin C, Dissmann E, Stuhmer W, Karschin A. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03559.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luscher C, Slesinger P. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:301. doi: 10.1038/nrn2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krapivinsky G, Gordon EA, Wickman K, Velimirović B, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. Nature. 1995;374:135. doi: 10.1038/374135a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi T, Ikeda K, Kojima H, Niki H, Yano R, Yoshioka T, Kumanishi T. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1091. doi: 10.1038/16019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yow TT, Pera E, Absalom N, Heblinski M, Johnston GA, Hanrahan JR, Chebib M. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aryal P, Dvir H, Choe S, Slesinger PA. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:988. doi: 10.1038/nn.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The MLSCN evolved into the MLPCN in 2008. For more information on the MLPCN and further details on the HTS effort, see: www.mli.nih.gov/mli/mlpcn.

- 11.Thallium flux assay protocol: Compounds were dissolved in DMSO, transferred to 384-well polypropylene plates, and serially diluted in DMSO using and Agilent Bravo (11-points, threefold dilutions). Serially diluted plates were dispensed to daughter plates using a Labcyte Echo555 and diluted to twofold over their target assay concentration with 20 mM HEPES-buffered (pH 7.4) Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), hereafter referred to as Assay Buffer, using a Thermo Fisher Combi. Twenty-thousand HEK-293 cells/well stably transfected with the ion channel subunits of interest (e.g., GIRK1/GIRK2, GIRK1/GIRK4) were plated into 384-well, black-walled, clear-bottom, aminecoated coated plates in 20 μL/well alpha-minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and incubated overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cell culture medium was removed from cell plates and replaced with 20 μL/well Assay Buffer. Twenty microliters/well of 0.5 μM of the thallium-sensitive dye, Thallos-AM (TEFlabs, Austin TX) in Assay Buffer was added to cell plates. Cell plates were incubated for ~60 min at room temperature and then dye-loading solution was removed from cell plates and replaced with 20 μL/well Assay Buffer. Dye loaded and washed cell plates were transferred to a Hamamatsu FDSS 6000 and a double-addition protocol was initiated. After 10s, 20 μL/well of 20 μM test compound in 0.2% DMSO and Assay Buffer was added. After 4 min 10 μL/well of a 5× sodium bicarbonate-based thallium stimulus buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 135 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaSO4, 1 mM MgSO4,5 mM glucose, 12 mM Tl2SO4) was added and 2 more minutes of data collection followed. Fluorescence data were collected at 1 Hz. Data analysis: Waveform signals (fluorescence intensity vs time normalized by dividing each fluorescence value (F) by the initial fluorescence value for each trace (F0)) were reduced to single values by subtracting the average normalized waveform from vehicle control wells from each wave on the plate followed by obtaining the slope of the change in fluorescence immediately after the addition of the thallium stimulus. Slope values were normalized as a percentage of the slope obtained by the addition of a maximally effective concentration of the GIRK activator, ML297 (e.g., an efficacy value of 100% means that the compound’s maximum apparent efficacy equals that of ML297). Curve fits for normalized slope values were obtained using a fourparameter logistic equation in the Excel add-in, XLfit.

- 12.Kauffman K, Days E, Romaine I, Du Y, Sliwoski G, Morrison R, Denton J, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Sulikowski GA, Xie S, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1021/cn400062a. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cn400062a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kennedy JP, Williams L, Bridges TM, Daniels RN, Weaver D, Lindsley CW. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:345. doi: 10.1021/cc700187t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsley CW, Wisnoski DD, Leister WH, O’Brien JA, Lemiare W, Williams DL, Jr, Burno M, Sur C, Kinney GG, Pettibone DJ, Tiller PR, Smith S, Duggan ME, Hartman GD, Conn PJ, Huff JR. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5825. doi: 10.1021/jm049400d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.General urea library: To a solution of 5-amino-N,N,2-trimethylbenzenesulfonamide (4) (15 mg, 0.07 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF (1.0 mL) was added an isocyanate (0.07 mmol, 1.0 equiv) at rt. After 12 h, the reaction was purified by reverse phase HPLC to afford the desired urea. General Amide Library: To a solution of 5-amino-N,N,2-trimethylbenzenesulfonamide (4) (15 mg, 0.07 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF and TEA (4:1, 1.0 mL) was added the acid chloride (0.084 mmol, 1.1 equiv) at rt. Once the reaction was complete by LCMS, the reaction was filtered and purified by reverse phase HPLC to afford the desired amide.General urea library: To a solution of 5-amino-N,N,2-trimethylbenzenesulfonamide (4) (15 mg, 0.07 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF and TEA (4:1, 1.0 mL) was added the acid chloride (0.084 mmol, 1.1 equiv) at rt Once the reaction was complete by LCMS, the reaction was filtered and purified by reverse phase HPLC to afford the desired amide.