Abstract

Background

Prior research indicates that assessments of lifetime alcohol use disorders (AUDs) show low sensitivity and are unreliable when assessed by a single, retrospective interview. This study sought to replicate and extend previous research by calculating the lifetime prevalence rate of AUDs using both single retrospective assessments of lifetime diagnosis and repeated assessments of both lifetime and past-year diagnoses over a 16-year period within the same high-risk sample. In addition, this study examined factors that contributed to the consistency in reporting lifetime AUDs over time.

Methods

Using prospective data, the reliability and validity of lifetime estimates of alcohol dependence and AUD were examined in several ways. Data were drawn from a cohort of young adults at high and low risk for alcoholism, originally ascertained as first-time college freshmen (N = 489 at baseline) at a large, public university and assessed over 16 years.

Results

Compared with using a single, lifetime retrospective assessment of DSM-III disorders assessed at approximately age 34, lifetime estimates derived from using multiple, prospective assessments of both past-year and lifetime AUD were substantially higher (25% single lifetime vs. 41% cumulative past-year vs. 46% cumulative lifetime). This pattern of findings was also found when conducting these comparisons at the symptom level. Further, these results suggest that some factors (e.g., symptoms endorsed, prior consistency in reporting of a lifetime AUD, and family history status) are associated with the consistency in reporting lifetime AUDs over time.

Conclusions

Based on these findings, lifetime diagnoses using a single measurement occasion should be interpreted with considerable caution given they appear to produce potentially large prevalence underestimates. These results provide further insight into the extent and nature of the reliability and validity problem with lifetime AUDs.

Keywords: Lifetime Diagnosis, Lifetime Prevalence, Alcohol Use Disorder, Reliability, Validity, Negative Prevalence

Lifetime prevalence of alcohol use disorders (AUDs; alcohol abuse and/or alcohol dependence [AD]) is derived from cross-sectional studies (e.g., Epidemiological Catchment Area study [ECA; Robins and Regier, 1991], the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS; Kessler et al., 1994], the National Comorbidity Survey—Replication [NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2005], the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiological Survey [Grant et al., 1994a, b, 2004], and the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol Related Conditions [NESARC], Grant et al., 2003). Despite that estimates derived from these studies have research and policy implications, there is limited but compelling evidence that cross-sectional, retrospective assessments result in gross underestimates of the prevalence of several disorders, including AUDs.

Moffitt and colleagues (2010) compared lifetime prevalence of several internalizing and externalizing disorders from a prospective, birth cohort study (The Dunedin Study; Moffitt et al., 2001) to 3 national cross-sectional studies (New Zealand Mental Health Survey [NZMHS; Degenhardt et al., 2008; Wells et al., 2006], the NCS, and the NCS-R). For all disorders, the prospective estimates were markedly higher compared with estimates derived cross-sectionally. These results indicate that lifetime prevalence of disorders is likely underestimated when based on a single assessment of lifetime diagnosis.

These huge underestimates of AUDs are alarming considering that researchers rely on prevalence rates from large cross-sectional studies to understand the etiology of disorders. For example, single, retrospective assessments have been used to define phenotypes of lifetime AUDs in genetic studies (including linkage and association studies; e.g., Gizer et al., 2011; Wall et al., 2005), deduce developmental subtypes of conduct disorder (Nock et al., 2006), and derive developmental subtypes of AUD (using both past-year and lifetime retrospective data) to understand the developmental course with implications for treatment and prevention of these disorders (Moss et al., 2007, 2010). Further, age of onset of psychiatric disorders is typically understood using lifetime retrospective data (e.g., Falk et al., 2008; Hesselbrock et al., 1985; Kessler et al., 2005). If lifetime prevalence rates from cross-sectional data are fundamentally flawed, then subsequent research relying on these types of data may be misleading. Therefore, it is imperative that researchers further characterize the reliability and validity problem with lifetime diagnosis to estimate the extent of the problem.

Although data from the Moffitt and colleagues (2010) study were provocative, there were a number of methodological limitations. (i) Cumulative lifetime prevalence for The Dunedin Study was calculated based on past-year assessments of AD at ages 18, 21, 26, and 32. Thus, considering the gaps in assessment between waves and that past-year, not lifetime, diagnoses were assessed, even the cumulative prevalence for AD derived from this study may be an underestimate. (ii) Multiple DSM criteria were used to calculate cumulative prevalence from ages 18 to 32. Strong evidence, shown in table 2 of Moffitt and colleagues (2010), indicates that DSM version impacts lifetime estimates of AD (i.e., DSM-III-R lifetime estimate from NCS was 16.9%, whereas DSM-IV lifetime estimates from NZMHS and NCS-R ranged from 6.3 to 6.4%). Thus, the cumulative lifetime estimates using consistent DSM criteria are currently unknown. (iii) Multiple data sets were used to compare the difference in prevalence from cross-sectional versus prospective data. As noted by Susser and Shrout (2010), inferences from this approach are limited by the methodological differences between the samples.

Previous research indicates that poor reliability in reporting may present in terms of individuals meeting criteria for a lifetime AUD at 1 time period, but failing to do so at a subsequent time period (i.e., negative prevalence; Jackson et al., 2006; Robins, 1985; Shrout et al., 2011; Vandiver and Sher, 1991). Evidence for negative prevalence comes from longitudinal studies varying in both assessment instruments and follow- up intervals (e.g., Copeland et al., 2011; Cottler et al., 1989; Culverhouse et al., 2005; DeMallie et al., 1995; Vandiver and Sher, 1991), indicating that the age-related decline in lifetime estimates observed in cross-sectional studies (e.g., ECA, NCS-R, and NESARC) may be due, in part, to individuals reporting less lifetime AUD symptoms as they age (Verges et al., 2011). Negative prevalence suggests issues with sensitivity (i.e., false negatives) in that each assessment does not consistently resolve the true prevalence rate of lifetime AUDs. Therefore, negative prevalence is indicative of problems with reliability (and, consequentially, validity) given the underestimation of lifetime prevalence rate of AUDs. A critical issue is “how badly?” the prevalence rate is underestimated.

FACTORS POTENTIALLY INFLUENCING RELIABILITY OF LIFETIME REPORTS

Despite the well-documented nature of the unreliability of lifetime estimates of AUDs, the factors that contribute to this phenomenon are not well understood (DeMallie et al., 1995). Some studies suggest that the reliability of lifetime estimates of AUDs is positively correlated with the severity of the diagnosis (e.g., previous treatment for AD; Culverhouse et al., 2005) and negative prevalence is largely driven by threshold cases at baseline (i.e., individuals who endorse just enough symptoms to warrant a diagnosis, which make up the majority of AUD diagnoses in a nonclinical sample; Culverhouse et al., 2005; Vandiver and Sher, 1991). Susser and Shrout (2010) suggested further study using longitudinal data is needed to better characterize lifetime prevalence. The purpose of this article was to characterize the lifetime prevalence curve using multiple approaches to assess lifetime prevalence and investigate factors that may explain differences in prevalence rates of lifetime AUDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The data were drawn from the Alcohol Health and Behavior study (Sher et al., 1991) beginning in 1987 with a sample of 489 first-year college students from a large Midwestern university. Participants were assessed at 6 subsequent occasions over a 16-year period.1 Data were collected from 383 participants at wave 7. Of the 489 participants at wave 1, 4 participants provided data at the first wave only, 122 provided data at 2 or more waves, and 363 participants provided data at every wave (overall 74% retention rate2). Attrition analyses indicated that those who provided data at 6 or fewer waves were more likely to have a past-year AUD, lifetime AUD, lifetime drug use disorder, and lifetime tobacco dependence at baseline. However there were no significant differences between the groups on several personality (e.g., neuroticism, extraversion, psychotocism) and cognitive (e.g., the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised [Wechsler, 1981] forward and backward digit span) variables. At baseline, the sample consisted of 53% women (mean age of 18.55 years [SD = 0.97]), 94% White, and 52% with a positive family history of paternal alcoholism (by design).

Measures

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) version III-A3 for the DSM-III criteria (Robins, 1985) was used to assess 12-month and lifetime AD and AUD diagnoses at every wave; however, the diagnostic criteria were revised multiple times throughout the study period. New DIS items were added as they became available (i.e., DIS-III- rev for the DSM-III-R criteria [Robins et al., 1989] and the DIS-IV for the DSM-IV criteria [Robins et al., 1997]) and original DIS items that varied from the new items remained in the interview for consistency throughout the study (see Table 1 for list of DSM criteria). Additional questions were added to the alcohol and drug modules of the DIS regarding age of onset, recent age, and the most recent time they experienced AUD symptoms (i.e., within the last 2 weeks, within the last month, within the last 6 months, within the last year, within the last 3 years, more than 3 years ago) and were used for past-year and lifetime diagnoses. AUD data were collected at waves 1 through 7 using DSM-III (APA, 1980) criteria, additional AUD data were collected at waves 3 through 7 using DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) criteria, and further AUD data were collected at waves 6 and 7 using DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria.

Table 1.

DSM Definitions of Alcohol Use Disorders

| Diagnosis | DSM Version | Symptom Clustering Criteria | Diagnostic Threshold | Diagnostic Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Abuse | DSM-III | The duration of disturbance is at least one month | Must endorse both symptoms to meet criteria for an abuse diagnosis |

|

| DSM-III-R |

|

At least 1 of symptoms must be endorsed to meet criteria for an abuse diagnosis | A maladaptive pattern of psychoactive alcohol use indicated by at least one of the following:

|

|

| DSM-IV |

|

At least 1 of 4 symptoms must be endorsed to meet criteria for an abuse diagnosis |

|

|

| Alcohol Dependence | DSM-III | The duration of disturbance is at least one month | Must endorse 1 of 2 abuse symptoms and physiological dependence (tolerance or withdrawal) to meet criteria for a dependence diagnosis |

|

| DSM-III-R | Some symptoms have persisted for at least one month or have occurred repeatedly over a longer period of time in order to meet diagnostic criteria; the diagnoses are hierarchical: dependence supersedes abuse | Must endorse at least 3 of 9 symptoms to meet criteria for a dependence diagnosis |

|

|

| DSM-IV |

|

Must endorse 3 of 7 symptoms to meet criteria for a dependence diagnosis |

|

Note. AD = alcohol dependence. AUD = alcohol use disorder. The diagnoses were hierarchical with dependence superseding abuse in DSM-III-R and IV. Sources: DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980; DSM-III-R (APA, 1987); DSM-IV-TR (APA, 1994).

Analyses

The analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The McNemar (1947) test was used to assess the statistical significance of base rate changes of lifetime prevalence across waves and across diagnostic systems. κ (Cohen, 1960) and Y (Yule, 1912) were used to determine diagnostic agreement across waves. DSM-III criteria (available at every wave) were used when examining the lifetime prevalence curve, the consistency in reporting AUD symptoms across waves, changes in the base rate of lifetime diagnosis, test–retest agreement, and consistent reporting with age.

Simple univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to investigate factors contributing to the consistency in reporting. These analyses were conducted using DSM-IV criteria from waves 6 to 7 (the only 2 waves with DSM-IV data available) because these criteria were the most up-to-date at the time. Consistency of diagnosing can be estimated by the percentage of individuals who report a lifetime AUD at baseline and continue to report at followup (i.e., consistency of diagnoses = 1 minus the negative prevalence among individuals with a baseline diagnosis). If an assessment is completely reliable, consistency in lifetime diagnosis should be 100%; once you have a “lifetime” diagnosis, you should not be able to “lose it.”

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Lifetime Prevalence Curve

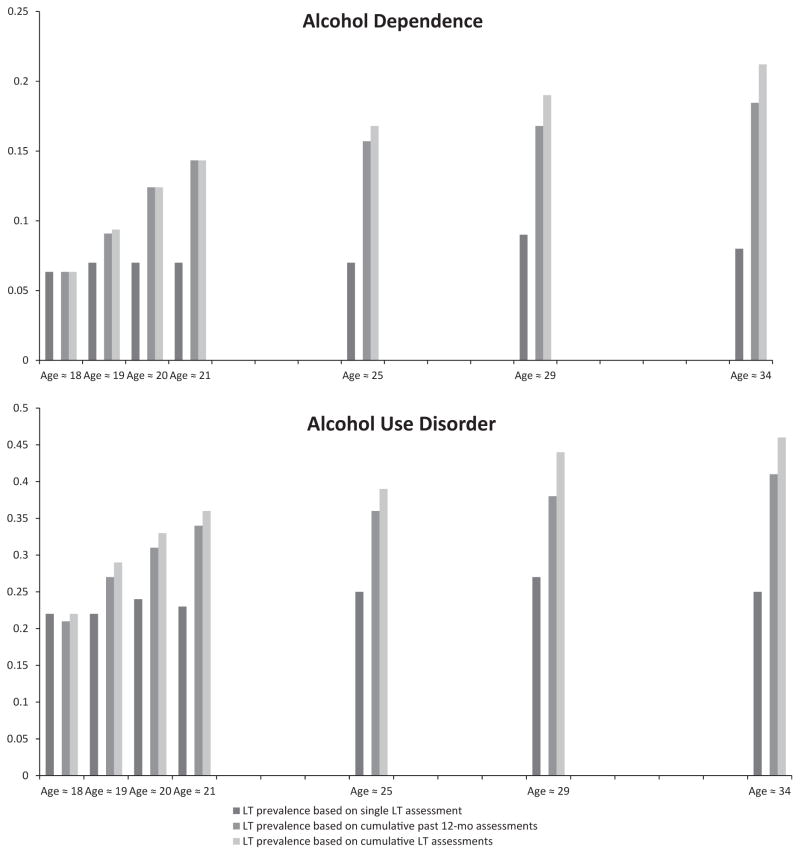

The AUD lifetime prevalence curves were examined using multiple prospective assessments and DSM-III criteria. Estimates of lifetime prevalence increased substantially when using cumulative reports over time compared with a single lifetime assessment (Fig. 1; Table 2). For example, at wave 7, the single, lifetime assessment using DSM-III criteria resulted in a prevalence of 25% for AUD. However, lifetime prevalence indicated by cumulative past-year reports at each wave (a replication of Moffitt et al., 2010) was 41% and cumulative lifetime assessments (i.e., includes individuals who ever diagnosed with a lifetime AUD at any wave including the final assessment) was 46%. Overall, these cumulative approaches produced substantially higher estimates than single-time-point assessments of lifetime disorder for DSM-III-R and DSM-IV (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

LT prevalence based on single LT assessment refers to the lifetime prevalence of a symptom from a single, age-specific assessment and does not take into account prior endorsement of the symptom. LT prevalence based on cumulative past-12-month assessments refers to the cumulative prevalence at a given age based on meeting past-year criteria at 1 or more prior waves but not the current estimate. LT prevalence based on cumulative LT assessments refers to the cumulative prevalence of a symptom at a given age based on lifetime endorsement of the symptom at 1 or more prior waves.

Table 2.

Percentage of Participants Diagnosed with Lifetime Alcohol Dependence (AD) and Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) at each Wave and Cumulatively across all Waves using DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV Criteria

| Estimates Derived from a Single, Retrospective Assessment | Estimates Derived from Prospective Assessments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Wave 1 (Age ≈ 18) N=489a |

Wave 2 (Age ≈ 19) N=484a |

Wave 3 (Age ≈ 20) N=472a |

Wave 4 (Age ≈ 21) N=471a |

Wave 5 (Age ≈ 25) N=457a |

Wave 6 (Age ≈ 29) N=410a |

Wave 7 (Age ≈ 34) N=383a |

Past-year Cumulative Waves 1–7 (Ages ≈ 18–34) N=489a N=449b N=423c |

Lifetime Cumulative Waves 1–7 (Ages ≈ 18–34) N=489a N=449b N=423c |

||

| DSM-III | AD | 6% (7%) | 7% (7%) | 7% (8%) | 7% (7%) | 7% (9%) | 9% (10%) | 8% (8%) | 19% (19%) | 21% (22%) |

| AUD | 22% (26%) | 22% (25%) | 24% (27%) | 23% (26%) | 25% (29%) | 27% (29%) | 25% (26%) | 41% (44%) | 46% (50%) | |

| DSM-III-R | AD | 25% (28%) | 26% (27%) | 29% (33%) | 26% (27%) | 26% (26%) | 40% (40%) | 48% (52%) | ||

| AUD | 28% (32%) | 28% (30%) | 32% (36%) | 28% (29%) | 29% (29%) | 42% (43%) | 50% (51%) | |||

| DSM-IV | AD | 13% (14%) | 13% (14%) | 11% (10%) | 18% (19%) | |||||

| AUD | 39% (40%) | 35% (36%) | 24% (28%) | 46% (47%) | ||||||

Note.

DSM-III criteria;

DSM-III-R criteria;

DSM-IV criteria.

The Ns at each wave represent the number of complete case data at that one time point. Given the longitudinal nature of the sample, the DSM criteria were revised and added to the assessments as they became available, so the Ns for the final two columns represent all nonmissing data available from for DSM-III criteria (waves 1–7), for DSM-III-R criteria (waves 3–7), and for DSM-IV criteria (waves 6 and 7). Percentages not in parentheses are based upon listwise deletion (N = 363) and percentages in parentheses based upon all nonmissing data available at that wave. Cumulative assessments were based on data at waves 1–7.

These findings replicate and extend Moffitt and colleagues (2010) indicating that lifetime prevalence estimated based on a single assessment (i.e., cross-sectional studies) of lifetime AUDs appears to seriously underestimate lifetime prevalence. Our findings also indicate that time-sampling past-year assessments, leaving intervening periods unassessed, and not reassessing earlier periods that had been surveyed result in somewhat lower estimates than would be attained using multiple lifetime assessments (Table 2). Notably, this is not a characteristic unique to DSM-III given that if we were to just compare the DSM-III-R or DSM-IV, estimates based on cumulative prevalence of lifetime, and past-year diagnoses at the last 2 waves, we would see a similar pattern of findings (Table 2). However, discrepancies between cumulative lifetime and cumulative past-year estimates in Table 2 appear to be much less when there are more assessment occasions over the life course covering periods of peak prevalence.

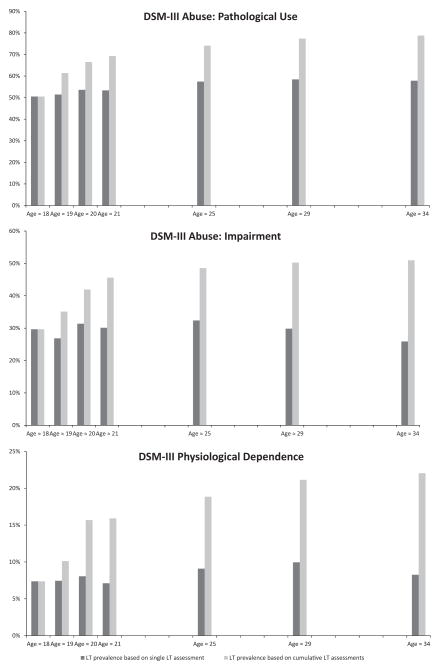

Consistency in Reporting AUD Symptoms Across Waves

The consistency in reporting lifetime AUD symptoms across waves was analyzed using the DSM-III criteria. For each of these symptoms, estimates based on cumulative assessments yielded increasingly higher prevalence rates than estimates based on a single measurement occasion as our cohort aged (Fig. 2). These results provide further evidence that single assessments are likely attenuated and the phenomenon is not driven by a single criterion.

Fig. 2.

LT prevalence based on single LT assessment refers to the lifetime prevalence of a symptom from a single, age-specific assessment and does not take into account prior endorsement of the symptom. LT prevalence based on cumulative LT assessments refers to the cumulative prevalence of a symptom at a given age based on lifetime endorsement of the symptom at 1 or more prior waves.

Changes in the Base Rates of Lifetime Diagnosis

Examination of Fig. 1 suggests that the prevalence of lifetime AUD and AD based on a single assessment was stubbornly similar despite the fact that participants were moving through their highest period of risk. We would anticipate that lifetime prevalence could increase as a function of the length of follow-up interval if the single, retrospective assessment showed high sensitivity. However, as shown in Table 3, only 3 of 21 McNemar tests showed differential base rates. To the extent that participants were still traversing the period of high risk for alcohol-related disorders, we would anticipate increases in the base rate of lifetime diagnosis as the cohort aged. However, this was not observed; only 3 of 21 comparisons were significant, and there was no obvious relation between the length of the assessment interval and significant change in base rates.

Table 3.

Stability of DSM-III Lifetime Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) over Varying Test-Retest Intervals (N = 383–489)

| Test-retest Interval in Years (n intervals) | Percent with L-AUD at Time 2 among those with a L-AUD at Time 1 | McNemar | Percent Agreement | κ | Yule’s Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=3) | 75; 76; 79 | 0.15; 1.23; 2.40 | 87%; 88%; 89% | .67; .68; .71 | .71; .71;.74 |

| 2 (n=2) | 68; 74 | 1.14; 0.21 | 83%; 85% | .56; .61 | .60; .65 |

| 3 (n=1) | 70 | 0 | 85% | .60 | .64 |

| 4 (n=2) | 70; 79 | 0.50; 4.31 | 82%; 85% | .56; .63 | .59; .67 |

| 5 (n=2) | 68; 75 | 1.43; 0.86 | 85%; 85% | .62; .60 | .65; .64 |

| 6 (n=1) | 72 | 6.70 | 81% | .52 | .57 |

| 7 (n=1) | 72 | 3.86 | 82% | .54 | .58 |

| 8 (n=1) | 69 | 2.85 | 81% | .51 | .55 |

| 9 (n=2) | 62; 68 | 0; 1.80 | 80%; 80% | .49; .50 | .53; .55 |

| 10 (n=1) | 67 | 5.63 | 79% | .46 | .51 |

| 11 (n=1) | 59 | 3.57 | 75% | .37 | .42 |

| 13 (n=1) | 63 | 1.32 | 80% | .47 | .52 |

| 14 (n=1) | 59 | 0.31 | 79% | .43 | .48 |

| 15 (n=1) | 56 | 2.18 | 77% | .36 | .42 |

| 16 (n=1) | 56 | 1.90 | 77% | .37 | .43 |

Note. Data was collected when participants were age 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 34. Column one represents the number of time intervals available to calculate agreement statistics in the data. For example, 1 (n=3) in the first row represent that there were three one-year time intervals (i.e., wave 1 to wave 2; wave 2 to wave 3; wave 3 to wave 4) used to calculate the agreement statistics for that time interval, and the final row indicates that there was one 16-year time interval (i.e., wave 1 to wave 7) used to calculate agreement statistics for that time interval. Bold McNemar values represent significance at alpha = .05; L-AUD = lifetime alcohol use disorder; κ = Kappa.

Test–Retest Agreement

The consistency in reporting lifetime diagnosis was measured in multiple ways. We examined the proportion of persons who diagnosed at baseline with a lifetime AUD that continued to diagnose with a lifetime AUD at follow-up.4 Logically, with a perfectly reliable diagnosis, this estimate would be 100%. However, as is clear in Table 3, the rediagnosis rate was always under 80% and tended to decrease with increasingly longer test–retest intervals. We also calculated traditional measures of diagnostic agreement (i.e., percentage agreement and κ and Y) across waves to characterize how agreement varies as a function of time interval between interviews. These measures indicate decreasing agreement over increasingly longer test–retest intervals. Importantly, these decreases in agreement cannot be attributed to systematic changes in base rates as, as noted above, these tended to be consistent despite logical expectation to the contrary.

Differences among diagnostic systems were compared at waves 6 and 7 (the only waves with DSM-III, III-R, and IV data) when participants were approximately 29 and 34 years of age, respectively. Minimal differences were found between diagnostic systems; all 3 diagnostic systems had fair to good agreement and yielded roughly comparable estimates for consistently reporting from waves 6 to 7 (68, 74, 71%, respectively; Table 4). Given the confounding of multiple DSM criteria used to assess AUDs in Moffitt and colleagues (2010), the question remained whether methodological differences in DSM criteria were influencing the prevalence rates. The present study indicates that the inconsistency in reporting lifetime AUDs over time is not a methodological phenomenon specific to the DSM criteria sets and algorithms used, but occurs across successive versions of the DSM.

Table 4.

Agreement Between Diagnostic Systems Between Waves 6 and 7

| Diagnostic system | Wave 6 L-AUD n |

Wave 7 L-AUD n |

McNemar | Percentage agreement | Kappa | Yule’s Y | Percentage consistently reporting L-AUD from waves 6 to 7 | Percentage onsetting between waves 6 and 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-III | 118 | 100 | 0.86 | 85 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 68 | 9 |

| DSM-III-R | 119 | 111 | 0.07 | 85 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 74 | 8 |

| DSM-IV | 163 | 136 | 2.38 | 81 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 71 | 8 |

L-AUD, lifetime alcohol use disorder.

No significant differences were found using the McNemar test. Negative prevalence = 1 minus the consistency in reporting. The inconsistency in reporting is represented by either negative prevalence or onsets. Notably, the fewer cases from waves 6 to 7 represent both missing data and negative prevalence, whereas the number of cases at wave 7 represents both consistent reporting over time and onset cases.

Consistent Reporting and Age

Considering that peak prevalence of AUDs is in the early 20s (e.g., Sher et al., 2005), younger individuals may be better reporters of their lifetime AUD than older individuals given that, on average, they will be retrospecting over shorter intervals. Upon examination of the consistency in reporting of lifetime AUDs using DSM-III criteria across age groups, we found that 70% consistently reported from ages 18 to 21, 70% consistently reported from ages 25 to 29, and 68% consistently reported from ages 29 to 34. This pattern of rates of rediagnosing suggests little bias as a function of age when retrospecting over a fixed interval of 3 to 5 years. Note, however, that we also found decreased consistency as a function of test–retest interval (see Table 3). This suggests that age-related differences in recall of lifetime episodes of AUD are related to the temporal remoteness of recall rather than age per se, at least in the relatively young ages surveyed in this study.

Predicting Consistency in Reporting

To investigate factors contributing to the consistency in reporting using the most relevant diagnostic criteria, correlates of consistency in reporting were investigated at waves 6 and 7 (the only 2 waves with DSM-IV data). Complete data were collected for 370 individuals from wave 6 (age = 29) to wave 7 (age = 34). Of those 370 participants, 48 (13%) met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime AD and 143 (39%) met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime AUD at wave 6. The rate of consistently diagnosing from waves 6 to 7 was similar for DSM-IV lifetime AD (67%; κ = 0.61; Y = 0.71) and AUD (71%; κ = 0.59; Y = 0.60).

Recency of the DSM-IV Lifetime Diagnosis

Logistic regression analysis indicated that a past-12-month diagnosis at wave 6 did not lead to significantly greater odds of rediagnosing for lifetime AD at wave 7 using DSM-IV criteria (OR = 1.31, 95% CI [0.30 to 5.45]). Similarly, a DSM-IV past-12-month AUD diagnosis at wave 6 did not lead to significantly greater odds of rediagnosing for a DSM-IV lifetime AUD at wave 7 (OR = 1.87, 95% CI [0.85 to 4.15]). Although there is a 5-year interval between waves 6 and 7, nonsignificant results were still found when using DSM-III criteria over two 1-year time intervals (OR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.30 to 2.57]; OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.01 to 4.48]) and remained so after adjusting for sex and family history.

Consistency in Prior Reporting of a DSM-III Lifetime AUD

Logistic regression analysis indicated that prior consistency in reporting of lifetime AUD (i.e., consistently diagnosing for a lifetime AUD at least 3 of 5 previous waves using DSM-III criteria) led to significantly greater odds of consistently diagnosing for a DSM-IV lifetime AUD at wave 7 (OR = 2.20, 95%CI [1.00 to 4.92]).

Consistency in Reporting Based on High-Risk Variables

Logistic regression analysis indicated that individuals with a positive family history of alcoholism had greater odds of consistently reporting lifetime AUD from waves 6 to 7 (OR = 2.20, 95% CI [1.39 to 3.48]), indicating that risk status contributes to consistently reporting over time. In addition, all individuals who endorsed 4 or more AD symptoms at wave 6 met criteria for DSM-IV lifetime AD at wave 7 indicating that in this subsample, negative prevalence for AD occurred solely with threshold cases. The relationship between number of AUD symptoms endorsed at wave 6 and consistently diagnosing with a lifetime AUD at wave 7 was more of a gradient, rather than a step, pattern. For example, 71% of individuals who endorsed 1 symptom at wave 6 consistently reported at wave 7, 95% of individuals who endorsed 5 symptoms at wave 6 consistently reported at wave 7, and 100% of individuals who endorsed 7 or more symptoms at wave 6 consistently reported at wave 7.

Given that negative prevalence was not found for individuals who endorsed 4 or more DSM-IV lifetime AD symptoms between waves 6 and 7, it appears that negative prevalence was driven by threshold cases of AD (consistent with previous research; i.e., Culverhouse et al., 2005; Vandiver and Sher, 1991). However, of the negative prevalence cases who endorsed 3 AD symptoms at wave 6 (n = 42), 38% reported zero symptoms at wave 7, 38%reported 1 symptom at wave 7, 12% reported 2 symptoms at wave 7, 10% reported 3 symptoms at wave 7, but not within the same 12-month period, and 2% endorse 5 symptoms at wave 7, but not within the same 12-month period. These data suggest that a larger portion of the individuals completely “forget” all or most of their AD symptoms entirely by the wave 7 interview, whereas fewer individuals actually make up just under threshold cases or individuals who endorse 3 or more symptoms, but do not meet the clustering requirement for DSM-IV. Research examining personality factors and other correlates of AUDs in negative prevalence cases and consistent reporters is currently under investigation (i.e., A.M. Haeny, A.K. Littlefield, K.J. Sher, in preparation).

Individuals who endorse more than 3 dependence symptoms presumably represent more severe phenotypes of the disorder. These results, and the results from previous studies, denote that severe forms of the disorder are more likely to be consistently reported over time. The diagnostic algorithm for AUD in the DSM-V (APA, 2013) is 2 or more of 11 symptoms clustering within the same 12-month period. It seems likely that those with mild AUD (i.e., threshold cases with 2 symptoms) will likely show poor lifetime reliability and those with more severe forms of AUD will show better reliability. However, a large proportion of persons in population-based studies are likely to be threshold cases. In NESARC, 12.4% of the U.S. sample was found to have a past-year DSM-V AUD with 5.15% (42% of those meeting threshold) endorsing 2 and only 2 symptoms (Martin et al., 2011). It, thus, seems likely that the DSM-V lifetime diagnosis will be found to have reliability problems similar to if not worse than DSM-IV in the general population. This is especially so as many of the 2-point symptom configurations reflect the most “mild” and unreliable symptoms at the individual symptom level (Martin et al., 2011).

DSM-IV Lifetime AUD Symptom Endorsed

Results from simple, bivariate logistic regression models indicated that endorsing the AUD symptoms (all of which were dependence items): tolerance (OR = 4.49, 95% CI [1.96 to 10.75]), larger/longer (OR = 3.18, 95% CI [1.39 to 7.55]), activities given up (OR = 5.05, 95% CI [1.38 to 28.07]), and physical/ psychological problems (OR = 6.11, 95% CI [1.39 to 56.05]), led to greater odds of consistently diagnosing for lifetime AUD at follow-up. In the simultaneous model, only tolerance was significant (OR = 3.25; 95% CI [1.34 to 8.11]) and remained so after adjusting for family history and sex (Table 5). The OR for withdrawal was inestimable because 100% of individuals who endorsed the symptom at baseline consistently reported a lifetime AUD at follow-up.

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Continued Diagnosis of DSM-IV Lifetime Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) at Follow-up From Type of Lifetime Symptom Endorsed Among those With Lifetime AUDs at Baseline (N = 143)

| Type of AUD symptom | n (%) Endorsing | Univariate unadjusted for sex and family history OR (CI) | Simultaneous unadjusted OR (CI) | Simultaneous adjusted for sex OR (CI) | Simultaneous adjusted for sex and family history OR (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neglect role obligations | 31 (22%) | 1.37 (0.50–4.21) | 0.16 (0.14–1.92) | 0.51 (0.14–1.88) | 0.26 (0.06–1.10) |

| Hazardous use | 124 (87%) | 1.23 (0.35–3.87) | 3.46 (0.79–15.21) | 3.62 (0.82–16.29) | 4.36 (0.98–19.41) |

| Legal problems | 21 (15%) | 1.55 (0.44–7) | 2.14 (0.57–10.19) | 1.92 (0.50–9.25) | 1.48 (0.34–6.47) |

| Social problems | 33 (23%) | 2.91 (0.96–10.76) | 1.64 (0.46–6.867) | 1.77 (0.48–7.65) | 2.47 (0.61–10) |

| Tolerance | 85 (59%) | 4.49 (1.96–10.75) | 3.25 (1.34–8.11) | 3.06 (1.25–7.67) | 4.76 (1.78–12.69) |

| Withdrawal | 14 (10%) | – | – | – | – |

| Larger/longer | 81 (57%) | 3.18 (1.39–7.55) | 1.90 (0.78–4.66) | 2.11 (0.84–5.37) | 1.99 (0.75–5.33) |

| Quit/control | 52 (36%) | 3.33 (1.32–9.33) | 1.74 (0.61–5.10) | 1.76 (0.63–5.28) | 2.08 (0.72–6.03) |

| Activities given up | 33 (23%) | 5.05 (1.38–28.07) | 1.86 (0.33–19.28) | 1.78 (0.32–18.44) | 3.80 (0.75–19.31) |

| Time spent | 26 (18%) | 2.51 (0.77–10.74) | 2.67 (0.65–15.87) | 2.56 (0.63–15.06) | 0.80 (0.19–3.33) |

| Physical/psychological problems | 27 (19%) | 6.11 (1.39–56.05) | 1.15 (0.29–5.55) | 1.18 (0.30–5.73) | 3.87 (0.52–29.03) |

AD, alcohol dependence; AUD, alcohol use disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95%confidence interval.

Baseline was at wave 6 when participants were on average 29 (SD = 1.03) years of age. Follow-up was at wave 7 when participants were on average 34 (SD = 0.82) years of age. The total N for both AD (48) and AUD (143) is equal to the number of individuals who diagnosed at wave 6 and provided data at wave 7. Withdrawal was inestimable due to a zero cell count (i.e., all individuals who endorsed withdrawal reliably diagnosed with lifetime disorders).

IMPLICATIONS

This study provides further evidence of the serious problems with single (or very limited) lifetime assessments of AUDs. Negative prevalence is actually much higher among internalizing disorders (e.g., Hasin et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2005; Moffitt et al., 2010; Vandiver and Sher, 1991). Underestimates of disorders can be prorated to reflect more precise estimates in the population; however, misleading substantive findings about the etiology and development of disorders are not easily corrected. Extensive research based on substantial underestimates of the prevalence of disorders may have insidiously infiltrated the field.

These methodological problems with lifetime assessment have been recognized for half a century (Gruenberg, 1963, p. 92) and discussed recently by a number of researchers (e.g., Moffitt et al., 2010; Streiner et al., 2009; Susser and Shrout, 2010). Given that there is no laboratory test or a biological marker of psychiatric disorders, it is difficult to confirm that we are accurately diagnosing individuals with and without a lifetime disorder. Despite the various limitations of lifetime measures, use of retrospective, lifetime, interview measures represents the most feasible approach for estimating lifetime prevalence for many if not most purposes. Replacing diagnostic interviews with more “objective” assessments (e.g., longitudinal, expert, all data [LEAD; Spitzer, 1983] or behavioral and neurocognitive symptoms [e.g., Morris and Cuthbert, 2012]) repeated over the life course may be impractical and not economically viable in most applications. Such “objective” diagnostic measures are not readily adaptable to obtain lifetime assessments. Given the difficulties of collecting prospective data over significant portions of the life course, some researchers (e.g., Streiner et al., 2009) have suggested abandoning lifetime measures entirely. However, for many purposes, there are few cost-effective alternatives, and lifetime diagnosis will continue to be used for the foreseeable future. Consequently, users of these measures should be aware of and acknowledge the nature and magnitude of measurement issues of lifetime assessments.

Lifetime prevalence should be conducted prospectively with multiple diagnostic assessments. The common practice of only assessing the time since last interview (e.g., Grant et al., 2006) should be replaced by lifetime interviews at each time point. Notably, a lack of a lifetime diagnosis at baseline is often a false negative, and subsequent reassessments often reveal a lifetime AUD that “should have” been diagnosed at an earlier interview, but was not (A.M. Haeny, A.K. Littlefield, K.J. Sher, in preparation). Such false negatives at baseline can yield false-positive assessments of “new onsets” at follow-up (A.M. Haeny, A.K. Littlefield, K.J. Sher, in preparation). Given these facts, it is suboptimal research practice to assume that a single baseline assessment for an AUD is sufficient if there is an opportunity to reassess.

Limitations

Factors that led to consistency in reporting lifetime AUDs were investigated in predominantly White, college-attending individuals who were on average 34 years of age at the time of the last assessment. These results may not generalize to individuals of all ages, ethnicities, or educational backgrounds. Generalizability may be limited due to biases related to attrition given that attriters were more likely to be affected by substance use disorders.5 Further, these findings are specific to the DIS and may vary depending on the structured interview used. Future research could investigate whether these variables predict consistency in reporting in more ethnically and educationally diverse samples of different ages and how consistency in reporting varies depending on the interview used.

Summary

The main points from this study include the following: (i) Lifetime prevalence of AUDs is likely substantially higher than suggested by large cross-sectional studies. (ii) Etiological and developmental research relying on cross-sectional retrospective data to investigate the etiology and correlates of disorders should be aware of the limitations of these estimates and be cautious when drawing definitive conclusions. (iii) Prevalence of lifetime disorders should be estimated prospectively across peak periods of use (e.g., late adolescence through early adulthood for AUDs) and synthesized using multiple follow-ups with shorter intervals between assessments. (iv) Given the relatively high cumulative estimates of AUD in this sample, even among family history–negative individuals (cumulative lifetime rates of DSM-III AUDs were 23 and 51% for females and males, respectively), these findings suggest that it is common (and even normative) for individuals to experience impairment, to some extent, from alcohol use during emerging and young adulthood, at least among this sample of college-attending young adults who matriculated at a campus with relatively high rates of binge drinking.6

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by NIAAA grants F31 AA019596 to AKL, T32 AA13526, R01 AA13987, R37 AA07231, and KO5 AA017242 to KJS, and P60 AA11998 to Andrew Heath. Portions of the work reported here were completed as part of the first author’s master’s thesis. The authors would like to thank Drs. Phillip K. Wood and Victoria Osborne for their assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Notably, this sample is the same as what was used in Vandiver and Sher (1991), but with 5 more waves of data and a 16-year versus 1-year maximum follow-up rate.

Seven individuals died during the study period.

The DIS-IIIA criteria for pathological use specify that an individual must endorse engaging in the following behaviors: ever wanted to stop drinking but could not, ever made rules to control drinking, ever drink a fifth of liquor or more in 1 day on more than 1 occasion, ever had blackouts while drinking, ever gone on binges or benders (kept drinking for a couple of days or more without sobering up) on 2 or more occasions, ever continue to drink knowing you had a serious physical illness that could be made worse, or has there ever been a period in your life when you could not do daily work without having a drink. The DIS-IIIA criteria for impairment designate that an individual must endorse experiencing at least 1 of the following circumstances: family ever object because you were drinking an excessive amount of alcohol, ever have friends, doctor, clergyman, or any other professional say you were drinking more than you should (with concerns other than losing weight), ever have problems at work or school due to drinking, ever lose a job or get kicked out of school due to drinking, ever gotten into trouble driving because of drinking, ever arrested or held at a police station due to drinking, or ever gotten into physical fights due to drinking. The DIS-IIIA criteria for physiological dependence indicate that an individual must endorse at least 1 of the following: ever drink at least 7 standard drinks every day for a period of 2 weeks, ever needed a drink just after getting up (i.e., before breakfast), or ever had shakes after cutting down or stopping drinking.

Given that there were 7 waves of data varying in time between assessments, baseline and follow-up, in this context, represent that agreement statistics were calculated using all possible test–retest intervals available in the data.

Attrition was very low for a study such as this with over 74% assessed at every diagnostic occasion over 16 years.

Notably, some population-based, large epidemiological samples have generated high single-point lifetime estimates as well (e.g., in NESARC the lifetime estimate of DSM-IV AUD was 30.3%; Hasin et al., 2007; for a detailed description of factors that contributed to this estimate, see Verges et al., 2011). Considering these data, our estimates do not appear to be inflated.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Author; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Author; Washington, DC: 1987. revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Author; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Author; Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient for agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: a prospective cohort analysis from the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JH. The reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. Br J Addict. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culverhouse R, Bucholz KK, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T, Bierut LJ. Long-term stability of alcohol and other substance dependence diagnoses and habitual smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:753–760. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Huang Y, Karam A, Kostyuchenko S, Lepine JP, Mora ME, Neumark Y, Ormel JH, Pinto-Meza A, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Takeshima T, Wells JE. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMallie D, Cottler LB, Compton WM. Alcohol abuse and dependence: consistency in reporting of symptoms over ten years. Addiction. 1995;90:615–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hilton ME. Age of onset and temporal sequencing of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders relative to comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizer IR, Edenberg HJ, Gilder DA, Wilhelmsen KC, Ehlers CL. Association of alcohol dehydrogenase genes with alcohol-related phenotypes in a Native American community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2008–2018. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Introduction to the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Health Res World. 2006;22:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hartford T, Dawson D, Chou P, Dufour M, Pickering R. Prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1992. Alcohol Health Res World. 1994a;18:243–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Moore TC, Kaplan KD. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Peterson A, Dawson DA, Chou SP. Source and Accuracy Statement for the 1992 National Longitudinal Epidemiology Survey (NLAES) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1994b. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg EM. A review of mental health in the metropolis. The mid-town Manhattan study. Millbank Q. 1963;41:77–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives Gen Psych. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbrock MN, Meyer RE, Keener JJ. Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Archives Gen Psych. 1985;42:1050–1055. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, O’Neill SE, Sher KJ. Characterizing alcohol dependence transitions during young and middle adulthood. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:228–244. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Steinley DL, Vergés A, Sher KJ. Letter to the Editor: the proposed 2/11 symptom algorithm for DSM-5 Substance Use Disorders is too lenient. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2008–2010. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex Differences in Antisocial Behavior: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency, and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Kokaua J, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Poulton R. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med. 2010;40:899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SE, Cuthbert BN. Research Domain Criteria: cognitive systems, neural circuits, and dimensions of behavior. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:29–37. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/smorris. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Subtypes of alcohol dependence in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Prospective follow-up of empirically derived alcohol dependence subtypes in wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC): recovery status, alcohol use disorders and diagnostic criteria, alcohol consumption behavior, health status, and treatment seeking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1073–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36:699–710. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN. Epidemiology: reflections on testing the validity of psychiatric interviews. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:918–924. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790320090013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz KK, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV) Washington University; St. Louis, MO: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Goldring E. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule III-rev. Washington University; St. Louis, MO: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood P, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N, Stadler GS, Jackson GL, Lane SP. Are there attenuation effects in repeated reports of college drinking patterns?. Poster session presented at the annual meeting for the Research Society on Alcoholism; Atlanta, GA. June.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL. Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry. 1983;24:399–411. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL, Patten SB, Anthony JC, Cairney J. Has ‘lifetime prevalence’ reached the end of its life? An examination of the concept. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18:221–228. doi: 10.1002/mpr.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser E, Shrout PE. Two plus two equals three? Do we need to rethink lifetime prevalence? Psychol Med. 2010;40:895–897. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandiver TA, Sher KJ. Temporal stability of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Verges A, Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. Did lifetime rates of alcohol use disorders increase by 67% in 10 years? A comparison of NLAES and NESARC. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:868–877. doi: 10.1037/a0022126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Shea SH, Luczak SE, Cook TA, Carr LG. Genetic associations of alcohol dehydrogenase with alcohol use disorders and endophenotypes in white college students. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:456–465. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-R Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wells JE, Oakley Browne MA, Scott KM, McGee MA, Baxter J, Kokaua J New Zealand Mental Health Survey Research Team. Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey: overview of methods and findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:835–844. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule GU. On the methods of measuring association between two attributes. J R Stat Soc. 1912;75:581–642. [Google Scholar]