Abstract

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) are particularly attractive for biomedical applications, because they exhibit a fluorescent signal in a spectral region where there is minimal interference from biological media. Although SWNT have been used as highly-sensitive detectors for various molecules, their use as in vivo biosensors requires the simultaneous optimization of various parameters, including biocompatibility, molecular recognition, high fluorescence quantum efficiency and signal transduction. Here we demonstrate that a polyethylene glycol ligated copolymer stabilizes near infrared fluorescent SWNT sensors in solution, enabling intravenous injection into mice and the selective detection of local nitric oxide (NO) concentration with a detection limit of 1 μM. The half-life for liver retention is 4 hours, with sensors clearing the lungs within 2 hours after injection, thus avoiding a dominant route of in vivo nanotoxicology. After localization within the liver, it is possible to follow the transient inflammation using NO as a marker and signalling molecule. To this end, we also report a spatial-spectral imaging algorithm to deconvolute fluorescence intensity and spatial information from measurements. Finally, we show that alginate encapsulated SWNT can function as an implantable inflammation sensor for in vivo NO detection, with no intrinsic immune reactivity or other adverse response, for more than 400 days. These results open new avenues for the use of such nanosensors in vivo for biomedical applications.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes as optical sensors are photostable and fluoresce in the near-infrared where blood and tissue absorption and autofluorescence is minimal1. SWNT have demonstrated single-molecule sensitivity, and can be functionalized to selectively detect a variety of molecules2, including alkylating chemotherapeutic drugs, hydrogen peroxide3,4 and NO5,6. SWNT have been functionalized for biocompatibility, demonstrating long circulation times7–11, favorable biodistribution in several mammalian animal models12,13, and highly favorably toxicological profiles for in vivo utility10,14–19. Proposed in vivo uses of SWNT include image contrast agents for bioimaging and drug delivery agents7,9, however their use as diagnostic sensors has not yet been demonstrated in vivo. Such use requires a synthetic strategy that incorporates biocompatibility, molecular recognition, high quantum efficiency and optical transduction of analyte binding.

In this work, we address these constraints by reporting the synthesis and operation of a complex that allows for analyte detection from within complex tissues and organs in vivo. The in vivo detection of nitric oxide (NO) is utilized as a model since it is a free-radical involved in diverse biological processes, such as apoptosis, neurotransmission, blood pressure control and innate immunity20 and has not been probed in intraperitoneal tissues. Current technology allows for in vivo NO detection through an electrochemical probe surgically implanted in a rat's brain21, but does not permit long term or non-invasive NO detection. Of critical importance to NO function is its steady-state concentration in tissues, with biologically relevant concentrations ranging over three orders-of-magnitude. On the basis of literature estimates, Thomas et al.22 proposed the following concentration categories for NO functions: (a) GMP-mediated signalling processes at 1–30 nM;(b) modulation of kinase and transcription factor activity at 30–400 nM; and (c) pathological nitrosative and oxidative stresses above 500 nM. Activated macrophages are the major source of pathologically high levels of NO23, producing local steady-state concentrations approaching 1 μM24. NO rapidly reacts with superoxide anion (O2˙−) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a potent oxidant. Peroxynitrite further reacts with CO2 to form nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCOO−), which decomposes into nitrogen dioxide (NO2˙) and carbonate radical (CO3˙−), which are also very strong oxidants. Overproduction of these reactive species in chronic inflammation can cause damage to all types of cellular biomolecules and thus contribute to the mechanistic link between inflammation and diseases such as cancer24,25. We tested single-walled carbon nanotubes in several contexts, including subcutaneously implanted sensors for inflammation detection and circulating sensors that localize within the liver for detection of reactive nitrogen species derived from NO. By specifically designing the chemical interface between organism and sensor, we show for the first time that in vivo detection using this type of platform is possible.

The chemical and optical constraints of in vivo sensing

Using the SWNT as a fluorescent sensor in vivo introduces additional complexities over those of a passive delivery agent or imaging fluorophore. The SWNT must be functionalized such that selective molecular recognition is enabled, and that recognition is transduced optically by the SWNT. However, the selective coating must also allow for biocompatibility and stability in vivo, a constraint that significantly limits the available interfaces that can be used. Fluorometric sensors based upon SWNT or other nanoparticles necessarily optimize the extent and selectivity of modulation for a particular analyte over interfering molecules4–6,26–29. However, operation in vivo adds the constraint that an adequate quantum yield must be maintained to allow detection from within tissue while remaining operable after conjugation with stabilizing components essential for in vivo biocompatibility.

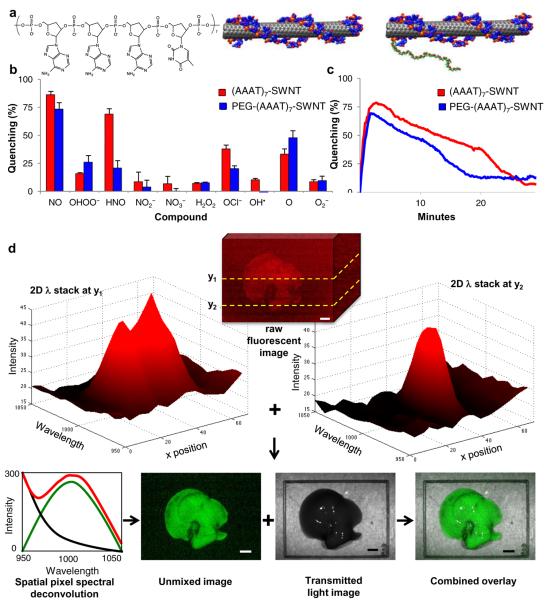

To address these constraints, we find that a DNA oligonucleotide ds(AAAT)7 allows for nitric oxide selectivity that is maintained after ligation to a 5 kDa MW poly ethylene glycol (PEG) segment (Fig. 1a). SWNT were dispersed using both the PEG-ligated and un-ligated DNA versions and tested for fluorescent modulation upon exposure to 30 μM nitric oxide and a battery of common potential interfering molecules, showing a 25% and 17% respectively greater reactivity to NO than any other analyte (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, addition of PEG decreases the SWNT response to HNO, and overall selectivity to NO is substantially higher than a diaminofluorescene standard, which measures only oxidation products of NO, and not the analyte directly, with an NO detection limit of less than 1 μM (Supplemental Fig. S1). The dynamic response and reversibility for both the PEG attached and unfunctionalized sensors appear in Fig. 1c. The rapid initial quenching rate is invariant for either construct, followed by a slower recovery due to solution degradation of the NO. The reversibility and rapidity of the response mean that for the first time this probe can be utilized to study NO signalling dynamics in vivo.

Figure 1. Characterization and 2Dλ imaging analysis of DNA wrapped SWNT complexes.

a, chemical composition of complex with d(AAAT)7 and wrapped (AAAT)7-SWNT and PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT. b,c Quenching activity of (AAAT)7-SWNT (red) and PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT (blue) sensors quantified by percent quenching of original fluorescence using a 785 nm photodiode following exposure to (b) RNS and ROS compounds (analyzed continuously for 10 minutes and once at the 12 hours post addition time point) with error bars representing standard error (c) NO (analyzed continuously for 30 minutes). (n = 3) d, 2Dλ imaging analysis for (AAAT)7-SWNT in an excised mouse liver 30 minutes after a tail vein injection of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT imaged with white light excitation and an emission spectrum from 950 to 1050 nm with a 10 nm step and 20 second accumulation time (scale bars 4 mm).

Spatial and Tissue Spectroscopic Imaging by Chemical Sensors

Unlike an invariant fluorescent or radiometric probe, an optical sensor must report both its position within the tissue and its chemical environment via either intensity or wavelength modulation. Hence, schemes that provide 2D static or dynamic images of fluorometric probes in vivo, and necessarily utilize intensity information to reveal location, cannot be used for chemical sensing. The development of liquid crystal tunable grading and filter technology provides a technological solution. By continuously tuning the grating to select a narrow wavelength space, an image stack I(x,y,λ)raw can be efficiently obtained via a rapid scan containing two spatial coordinates and the wavelength axis. We utilized a liquid crystal filter that afforded wavelength detection from 950 to 1050 nm, imposed upon a conventional whole animal field of view in a dark-box imaging configuration. The 2Dλ image stack easily encodes both spatial and chemical information, as demonstrated by the deconvolution of the raw stack to background and sensor components, allowing comparative fluorescence quenching (Fig. 1d). We find that the narrow fluorescent full width at half maximum of the PEG SWNT sensor (100 nm) is easily deconvoluted from the sloping autofluorescence background typically encountered in natural and synthetic media. Using a custom Matlab algorithm (see Supplemental Information) applied to SWNT immobilized within tissue, we rapidly reduce the raw image intensity stack I(x,y,λ)raw into SWNT fluorescence, background and autofluorescent noise components:

Here, k is a proportionality constant of calibration (assumed linear) containing the molar extinction coefficient of the SWNT probe (4400 +/− 1000 M−1 cm−1)30. Note that this scheme easily lends itself to the multiplexing of fluorescent sensors in the wavelength band, or the analysis of the autofluorescence background or tissue absorption simultaneously with the SWNT sensor probe. Unless otherwise noted, fluorescent images in this work are I(x,y)SWNT spatial maps in which fluorescent intensity corresponds to relative NO concentration via quenching once normalized31. To find the relative contribution of the SWNT fluorescence, background and autofluorescence noise at each point, a least squares minimization of a linear fit of the fluorescence spectrum was performed (see Supplemental Information).

Stability to Tail Vein Injection

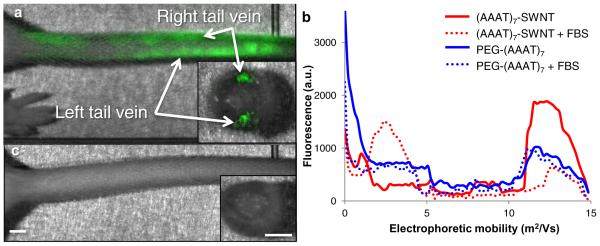

Ligation of PEG to the sensor interface is critical for successful circulation in vivo. For example, we find that (AAAT)7-SWNT does not circulate, instead accumulating near the injection site, as shown using near-infrared imaging in Fig. 2a. Figure 2a shows the administration of (AAAT)7-SWNT to first the left and then the right tail vein of a mouse. This procedure was done repeatedly with similar results; (AAAT)7-SWNT blocks the tail vein, inhibiting solution injection and blood flow. The insert in the image shows a cross section of the tail with the (AAAT)7-SWNT located within the veins, not the surrounding tissue. Hence, the vein occlusion was attributable to instability of the (AAAT)7-SWNT and not to erroneous injection. Further experiments show that tail vein blockage is caused by aggregates of serum proteins adsorbed to (AAAT)7-SWNT. Gel electrophoresis in Fig. 2b shows four samples ((AAAT)7-SWNT and PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT samples incubated with either fetal bovine serum (FBS) or buffer for 5 minutes before loading) and their migration distances as measured by fluorescence emission versus position. The zero point is the edge of the well with the fluorescence intensity measured at 1 mm distance intervals for all samples. The electrophoretic mobility of (AAAT)7-SWNT is 11*109 to 14*109 m2 V−1 while its FBS containing counterpart's mobility is 2*109 to 4*109 m2 V−1; confirming adsorption of FBS to (AAAT)7-SWNT. Both the PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT solutions with and without FBS had electrophoretic mobilities of 10*109 to 14*109 m2 V−1 with no perceptible difference between the two, confirming that the PEG moiety on the PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT prevents FBS adsorption. Our hypothesis that tail vein occlusion was caused by protein binding to (AAAT)7-SWNT was confirmed by visual inspection of the clearance of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT following injection into the vein, as shown in Fig. 2c. We conclude that addition of PEG moieties is necessary to produce stable preparations for in vivo circulation of this type of sensor.

Figure 2. Effect of PEGylation for tail vein injected SWNT.

a, (AAAT)7-SWNT remains within the tail following injection (50 mg L−1) into left then right tail veins, cross-sectional view of tail shows that the (AAAT)7-SWNT is localized within the veins. b, Gel electrophoresis data showing the difference in electrophoretic mobility of (AAAT)7-SWNT (red) when mixed with FBS as opposed to PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT (blue) which was not altered by the addition of FBS. c, Mouse tail following injection (50 mg L−1) of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT into the left tail vein, cross-sectional view shows clearance of SWNT from the vessel. (n = 3, scale bars 2 mm)

Circulation Time and Biodistribution

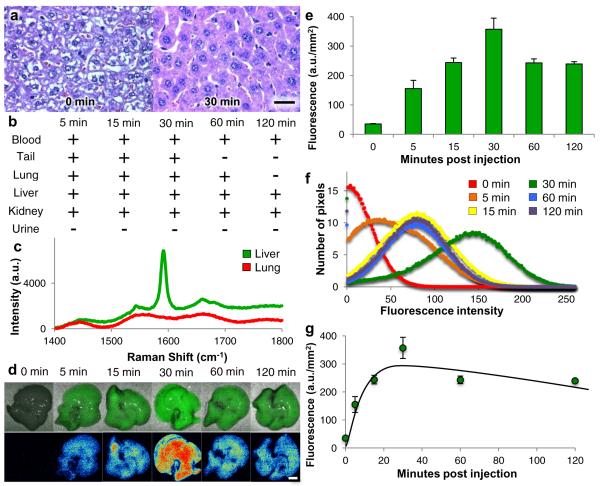

Having optimized intravenous administration of SWNT, we turned our attention to biodistribution and biocompatibility of SWNT as it is injected and localized within tissue, with results shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a presents histology of liver tissue (tail, lung and kidney tissues are shown in Supplemental Fig. S2) before and after injection of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT, and shows no evidence of an inflammatory response. Animals were injected with PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT via the tail vein, then sacrificed at 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the injection (n=3–5 mice per time point); 0 min time point represents control animals that did not receive PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT. Histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained tissues shows no detectable evidence of inflammation in tail, lungs, liver or kidneys at any time. Figure 3b shows the presence (+) or absence (−) of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT in tissue samples, as determined by Raman spectroscopy (n=3 mice per time point) (sample spectrum shown in Fig. 3c). Resonance Raman spectroscopy of blood and urine samples shows the presence of SWNT in blood at all points, but no SWNT in urine samples collected from the bladder at each time point, confirming that SWNT remains in vivo for at least 2 hours. PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT was also detected in liver and kidneys for the entire 2 hour time interval, but cleared the tail injection site within 1 hour. Clearance of SWNT from the lungs is particularly noteworthy. Due to the highly vascularized nature of lung tissue and its position within the systemic circulation, the lungs are highly susceptible to nanoparticle trapping32–34. Remarkably, visual inspection revealed darkening of the lung tissue 5 minutes after injection, but tissue returns to pretreatment coloration within 30 minutes. This observation was documented quantitatively by Raman tissue spectroscopy, which confirmed that PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT was detectable in the lungs 5 minutes after injection but cleared within two hours. This evidence directly supports the ability of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT to penetrate restrictive capillary networks without causing occlusions.

Figure 3. Biodistribution and biocompatibility of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT in 129 mice.

Data from mice sacrificed at various time points following tail vein injection of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT (200 μL injection of 50 mg L−1 SWNT) a, Histology images (H&E stained, 60× magnification, scale bar 10 μm) of liver tissue sections for control mouse and mouse received PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT 30 minutes before sacrifice revealing biocompatibility of SWNT due to lack of inflammatory cell recruitment. b, A representation of SWNT presence (+) or absence (−) in blood, tail (site of injection), lung, liver, kidney and urine following sacrifice and excision (as determined by Raman spectroscopy on fresh samples). c, representative Raman spectrum of those used to determine SWNT localization in (b). d, Images of excised livers deconvoluted with 2Dλ technology showing first PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT localization relative in the liver then a heatmap of fluorescence (scale bar 4 mm). e, Chart with quantification of SWNT fluorescence in mouse livers excised at various time points following tail vein injection of 200 μL of 50 mg L−1 PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT. (n = 3–5 mice per time point, error bars are s.e.m.) f, Graph of SWNT fluorescence distribution in mouse livers shown in e, shows similar peak values (10.5, 11.2, 8.1, 9.6 and 10.4) and standard deviations (73.19, 56.43, 63.07, 48.92 and 49.51 a.u.) for all time points. g, Mathematical model of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT concentration in mouse liver over time (same livers as those shown in e).

We observed PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT accumulation in multiple tissues, but noted the highest concentration in the liver. Figure 3d,e summarizes qualitative and quantitative evidence of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT accumulation in excised livers of mice sacrificed 5, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after injection, as in the biodistribution study described above. Representative images of the liver clearly show an increase in SWNT fluorescence up to 30 min, followed by a small decrease. Quantitative analysis, performed with the 2Dλ approach described in Fig. 1, shows that the average fluorescence for the livers increases up to 30 min, then decreases slightly and stays constant up to 60 and 120 min. Samples that have been quenched show a fluorescence distribution with larger standard deviations and lower peak value compared to non-quenched samples, shown in Supplemental Fig. S3. The fluorescence distribution of the data from Fig. 3e, shown in Fig. 3f, shows similar peak values and standard deviations for all time points, implying an increase and then decrease in PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT concentration within the liver as opposed to SWNT quenching after the 30 min time point.

Accumulation of the PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT in the liver can be modeled (see supplementary information), regression of the data in Fig. 3e yields a SWNT concentration within the liver of B(t) = B0(e−k1t − e−k2t), where B0 is −346.51, k1 is 0.1169 and k2 is 0.00288 and a half life of approximately 4 hours (see detailed description in Supplementary Information). More accurate liver half-life values require a more detailed model informed by longer time points, the focus of future efforts. Also of interest are blood concentration studies to enable for bloodstream half-life determination.

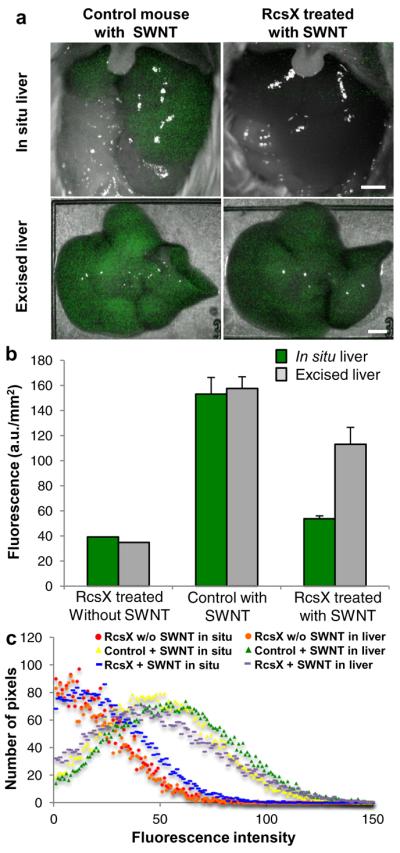

Detection of Nitric Oxide in Inflamed Mouse Liver

Having established the detectability of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT in mouse livers, we assessed the ability of the sensor to detect NO produced during inflammation in vivo. For this purpose, we could have used any mouse model, but chose the SJL mouse due to its intense inflammatory response resulting in massive overproduction of NO over a predictable time course after induction by an injection of RcsX tumor cells, as previously described35. Accordingly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with RcsX cells35 or saline (n=10, repeated once with n=5). After 12 days, PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT was injected into the tail vein of anesthetized mice, and 30 minutes later a cut in the abdominal cavity exposed the liver to allow in situ imaging (Fig. 4a). Immediately thereafter the animal was sacrificed, the liver excised and the isolated organ imaged a second time. Comparison of in situ images shows that livers of control animals clearly displayed fluorescence, whereas it was undetectable in inflamed organs of RcsX treated mice. In contrast, images of excised livers show that similar levels of SWNT fluorescence are present in both RcsX and control animals. We conclude that absence of fluorescence in the in situ images was attributable to NO generated during inflammation, since SWNT was clearly present in the organs as shown by fluorescence in excised organs. The rapid recovery of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT fluorescence after exposure to NO (Fig. 1c) is consistent with this interpretation. Quantification of these data was performed (Fig. 4b) and showed a 55% difference between pre- and post-sacrifice fluorescence in inflamed tissues compared to 3% difference in controls. Fluorescence distribution data shows the similarity between tissue of control mice without SWNT and the signal detected in the inflamed animals with injected SWNT (39 and 54 a.u. mm−2 compared to 153 a.u. mm−2 for non-inflamed mice with SWNT) while the excised liver samples for both inflamed and non-inflamed mice have similar standard deviations (48.14 and 43.41 a.u.) and peak values (148 and 158 a.u.). A limitation of this study is the need to expose the liver for in situ imaging, which we propose to address by further optimization of the SWNT to enable deeper tissue imaging or the use of a laproscopic probe to allow imaging with an even smaller incision than currently used.

Figure 4. In vivo sensor quenching due to inflammation.

a, Inflamed (RcsX treated) and control (healthy) mice imaged in situ 30 minutes after tail vein injection of PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT (200 μL injection of 50 mg L−1 SWNT) with their livers exposed then the excised liver imaged immediately following sacrifice, displaying the SWNT quenching that is observed in the inflamed animal (scale bars 4 mm). b, Chart showing quantification of SWNT fluorescence, including an extra control of a RcsX treated (inflamed) mouse that received a tail vein injection of saline. (n = 10, error bars are s.e.m.) c, Graph of SWNT fluorescence distribution in mouse livers shown in a and b.

A Nitric Oxide Monitor for Epidermal Tissue Inflammation

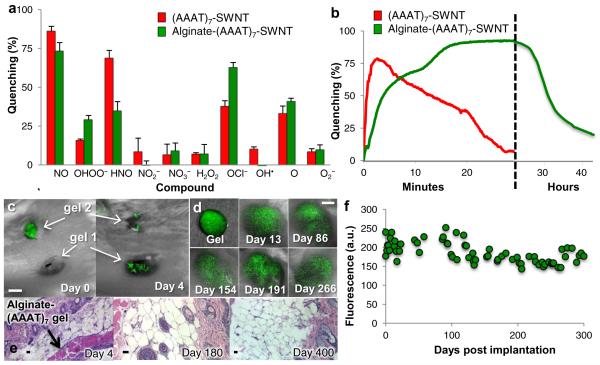

We also investigated the potential of tissue-specific localization of (AAAT)7-SWNT using an alginate-encapsulated sensor platform that can be implanted and perform on a multiple day/months time scale as opposed to the shorter time scale utilized by the intravenously injected PEG-(AAAT)7-SWNT. Figure 5a shows that the alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT sensor retains its NO specificity. Interestingly, the fluorescence signal was quenched less rapidly by NO, reaching 93% quenching after 30 minutes of NO exposure (Fig. 5b). The signal remained quenched for 24 hours, after which it returned to 25% after 41 hours. Several possible mechanisms could be responsible for the delayed fluorescence recovery. It is possible that NO adsorbed to alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT is more stable than free NO, increasing its half-life significantly and causing the NO to be concentrated in the alginate hydrogel. It is also possible that a long-lived reactive derivative of NO is responsible for the quenching of the alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT system. This seems plausible if the NO enters the alginate hydrogel and reacts with another negatively charged analyte trapped in the alginate matrix. Another possibility is that NO forms an alginate intermediate that quenches the SWNT.

Figure 5. Additional sensor construct with broader in vivo localization possibilities and long term sensing capabilities.

a,b Quenching activity of (AAAT)7-SWNT (red) and Alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT (green) sensors quantified by percent quenching of original fluorescence using a 785 nm photodiode following exposure to (a) RNS and ROS compounds (analyzed continuously for 10 minutes and once at the 12 hours post addition time point) with error bars representing standard error (b) NO (analyzed continuously for 30 minutes for (AAAT)7-SWNT and just under 45 hours for Alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT) (dashed vertical line represents a change in the timescale from minutes to hours). (n = 3) c, Image of mouse following implantation of two Alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT gels on day 0 (immediately after implantation of gel 2) and on day 4 after the fluorescence has returned. (scale bar 4 mm) d, Images of Alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT gel prior to subcutaneous implantation and at various time points throughout the 300 day test period (scale bar 4mm) and (e) quantification of peak SWNT fluorescence for one of the mice tested displaying long term consistency of SWNT signal. f, Histology images (H&E stained, 10x (day 4 and day 400) and 20x (day 180), scale bars 10 μm) from mice sacrificed at three different time points following the subcutaneous implantation of Alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT show very little to no inflammation.

Subcutaneous implantation and NO detection was performed with alginate encapsulated (AAAT)7-SWNT, with results shown in Fig. 5. The first study (Fig. 5c), involved subcutaneous placement of two alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT gels on both the left and right flanks of a mouse. We observed total signal quenching of gel 1 in the first image, taken approximately 20 minutes after the gel was placed, while gel 2 retained its fluorescence. In a subsequent image, after gel 2 was in the animal for approximately 20 minutes, gel 2 was also quenched. By day 4 both gels regained their fluorescence. Few quantitative data are available on in vivo levels of NO, which are thought to be very low (i.e., nM) in non-inflamed tissues. However, during a wound healing study by Lee et al. it was shown that NO levels in rat wound fluid increased steadily from 27 to 107 μM over a 14 day period, with nitric oxide synthase activity peaking at 24 hours post injury36. Therefore the concentration of NO in the wound bed can be high enough to quench the SWNT shortly after implantation. In our study with alginate gels in mice we did not see the prolonged NO presence that Lee et al. observed with polyvinyl alcohol sponges in rats, but we also did not see the recruitment of macrophage cells, known NO producers, or foreign body response that has been associated with polyvinyl alcohol sponges36,37. These observations support the interpretation that the absence of signal observed on day 0 of our experiments resulted from fluorescence quenching associated with a burst of NO due to gel implantation, not to tissue interference with the fluorescence. This fast quenching and multiple day signal recovery corresponds to the data shown in Fig. 5b. Tissue from the animal was collected post-sacrifice on day 4 and stained with H&E (Fig. 5e). Negligible inflammation was present at the site of implantation, also supporting our hypothesis relating to the fluorescence signal recovery that was observed.

Figure 5d and 5f shows the results from an unprecedented long-term durability study of the alginate-(AAAT)7-SWNT. Here, a single subcutaneous gel implantation into the right flank was monitored and fluorescence imaged for 60 to 400 days, far longer than implantable electrochemical sensors, the closest current technology, have been shown to monitor NO38. In Fig. 5d the gel is shown prior to implantation and then in vivo for multiple points during a 300 day study. Prominent fluorescence can be seen throughout the 300 days of the study. Gel morphology appears to change slightly over time due to animal movement, but the gel remains intact and the signal is largely invariant, as seen in Fig. 5f. Quantification of fluorescence intensity over the experimental time course is charted in Fig. 5f (signal recovery after implantation shown in Supplemental Fig. S4). . The signal was retained over the entire period, with variability of 14% in intensity. The small variation suggests that local NO concentration may have changed slightly over the 10 month period, but remained lower than the initial rise observed at the time of implantation, possibly caused by tissue damage involved in the surgical procedure. Consistent with this interpretation, inflammation was not observed in tissue surrounding the sites of gel implantation at the conclusion of the long-term studies (Fig. 5e). A particularly compelling aspect of these findings is that a change in SWNT concentration within the alginate gels or an alteration in gel composition (Supplemental Fig. S5) changes the timescale and degree of signal quenching. Hence, a sensor library can be constructed to contain gels with different NO concentration limits, allowing for specification directly related to the disease or condition of interest.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown a reversible, direct optical sensor for in vivo NO detection with a detection limit of about 1 μM made with semiconducting SWNT, thus demonstrating that such sensors hold high potential for in vivo chemical detection. Due to the absence of photobleaching, SWNT are virtually stable for years (we report activity for 400 days observing negligible change of activity). We have demonstrated two modes of operation for functionalized SWNT sensors: injection followed by localization within the liver and direct implantation within a specific tissue. We envision that the latter mode could be used to directly study tissue inflammation, cancer activity and cell signalling39,40.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health T32 Training Grant in Environmental Toxicology ES007020 (N.I.), National Cancer Institute Grant P01 CA26731, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant P30 ES002109, Beckman Young Investigator Award and National Science Foundation Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers to M.S.S., the TUBITAK 2211 and 2214 Research fellowship program (F.S. and S.S.), and the METU-DPT-OYP program (F.S and S.S). A Biomedical Innovation grant from Sanofi Aventis to M.S.S. is appreciated. The authors wish to thank T. Grusecki for assistance with the deconvolution code, as well as R. Langer, D. Anderson and P. Dedon for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Author contributions M.S.S. conceived of the original concept, with experimental design of in vivo experiments from G.W., M.S.S., N.I. and P.B. Sensor design and synthesis were performed by P.B., M.S., S.S, F.S., T.M., N.R. and N.I. N.I., L.T., M.S., V.I., E.A. and E.F. performed and analyzed the in vivo studies, N.I., P.B., M.S., T.M. and N.R. optimized the animal imaging system, V.I. and N.I. designed the mathematical model and computer program to deconvolute the data, and N.P. read and interpreted the histology slides. The manuscript was written by M.S.S and N. I. with contributions from G.W., P.B., L.T. and T.M.

Additional Information Supplementary information accompanies this paper at www.nature.com/naturenanotechnology. Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Wray S, Cope M, Delpy DT, Wyatt JS, Reynolds EO. Characterization of the near infrared absorption spectra of cytochrome aa3 and haemoglobin for the non-invasive monitoring of cerebral oxygenation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;933:184–192. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(88)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heller DA, et al. Multimodal optical sensing and analyte specificity using single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:114–120. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin H, Heller DA, Kim JH, Strano MS. Stochastic Analysis of Stepwise Fluorescence Quenching Reactions on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Single Molecule Sensors. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4299–4304. doi: 10.1021/nl802010z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin H, et al. Detection of single-molecule H2O2 signalling from epidermal growth factor receptor using fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:302–309. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, et al. The rational design of nitric oxide selectivity in single-walled carbon nanotube near-infrared fluorescence sensors for biological detection. Nat Chem. 2009;1:473–481. doi: 10.1038/nchem.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang JQ, et al. Single Molecule Detection of Nitric Oxide Enabled by d(AT)(15) DNA Adsorbed to Near Infrared Fluorescent Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:567–581. doi: 10.1021/ja1084942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, et al. Optimization of surface chemistry on single-walled carbon nanotubes for in vivo photothermal ablation of tumors. Biomaterials. 2011;32:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, et al. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, et al. Drug delivery with carbon nanotubes for in vivo cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, et al. Circulation and long-term fate of functionalized, biocompatible single-walled carbon nanotubes in mice probed by Raman spectroscopy. P Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:1410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707654105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z, et al. Supramolecular stacking of doxorubicin on carbon nanotubes for in vivo cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:7668–7672. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherukuri P, et al. Mammalian pharmacokinetics of carbon nanotubes using intrinsic near-infrared fluorescence. P Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:18882–18886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609265103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh R, et al. Tissue biodistribution and blood clearance rates of intravenously administered carbon nanotube radiotracers. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3357–3362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509009103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai H. Carbon nanotubes in biology and medicine: In vitro and in vivo detection, imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 2009;2:85–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Tabakman SM, Chen Z, Dai H. Preparation of carbon nanotube bioconjugates for biomedical applications. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1372–1381. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson JT, et al. High performance in vivo near-IR (> 1 μm) imaging and photothermal cancer therapy with carbon nanotubes. Nano Res. 2010;3:779–793. doi: 10.1007/s12274-010-0045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Y, et al. Influence of length on cytotoxicity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes against human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 in vitro and subcutaneous tissue of rats in vivo. Mol BioSyst. 2005;1:176–182. doi: 10.1039/b502429c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schipper ML, et al. A pilot toxicology study of single-walled carbon nanotubes in a small sample of mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsher K, et al. A route to brightly fluorescent carbon nanotubes for near-infrared imaging in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:773–780. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SS, et al. Real-Time in Vivo Simultaneous Measurements of Nitric Oxide and Oxygen Using an Amperometric Dual Microsensor. Anal Chem. 2010;82:7618–7624. doi: 10.1021/ac1013496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas DD, et al. The chemical biology of nitric oxide: implications in cellular signaling. Free Radical Bio Med. 2008;45:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis RS, Tamir S, Tannenbaum SR, Deen WM. Kinetic analysis of the fate of nitric oxide synthesized by macrophages in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29350–29355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dedon PC, Tannenbaum SR. Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barone PW, Baik S, Heller DA, Strano MS. Near-infrared optical sensors based on single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nat Mater. 2005;4:86–U16. doi: 10.1038/nmat1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heller DA, et al. Optical Detection of DNA Conformational Polymorphism on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Science. 2006;311:508–511. doi: 10.1126/science.1120792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn JH, et al. Label-free, single protein detection on a near-infrared fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube/protein microarray fabricated by cell-free synthesis. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2743–2752. doi: 10.1021/nl201033d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JH, Chen KH, Strano MS. Aptamer-capped nanocrystal quantum dots: a new method for label-free protein detection. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15584–15585. doi: 10.1021/ja066506k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoppler F, et al. Molar Extinction Coefficient of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. J Phys Chem-US. 2011;115:14682–14686. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Organic fluorometric probes, either in a turn-on or turn-off mode, require a reference to convey quantitatively spatial and chemical information simultaneously, and the SWNT probes are no different in this respect.

- 32.Donaldson K, et al. Carbon Nanotubes: A Review of Their Properties in Relation to Pulmonary Toxicology and Workplace Safety. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92:5–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacerda L, Bianco A, Prato M, Kostarelos K. Carbon nanotubes as nanomedicines: From toxicology to pharmacology. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2006;58:1460–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poland CA, et al. Carbon nanotubes introduced into the abdominal cavity of mice show asbestoslike pathogenicity in a pilot study. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:423–428. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gal A, Tamir S, Tannenbaum S, Wogan G. Nitric oxide production in SJL mice bearing the RcsX lymphoma: A model for in vivo toxicological evaluation of NO. P Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:11499–11503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee RH, Efron D, Tantry U, Barbul A. Nitric Oxide in the Healing Wound: A Time-Course Study. J Surg Res. 2001;101:104–108. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson JM. Animal Models for Wound Repair. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:S1–S11. doi: 10.1007/pl00007448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griveau S, Bedioui F. Overview of significant examples of electrochemical sensor arrays designed for detection of nitric oxide and relevant species in a biological environment. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405:3475–3488. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric Oxide: A Physiologic Messenger Molecule. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.