Abstract

Over the past decade, the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has changed the landscape of S. aureus infections around the globe. Initially recognized for its ability to cause disease in young and healthy individuals without healthcare exposures as well as for its distinct genotype and phenotype, this original description no longer fully encompasses the diversity of CA-MRSA as it continues to expand its niche. Using four case studies, we highlight a wide range of the clinical presentations and challenges of CA-MRSA. Based on these cases we further explore the globally polygenetic background of CA-MRSA with a special emphasis on generally less characterized populations.

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), Community-associated (CA)-MRSA, Hospital associated (HA)-MRSA

1 Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen and colonizer in approximately 30–50 % of individuals on mucosal surfaces and the skin [1]. S. aureus causes a wide spectrum of disease including skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), pneumonia, bacteremia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis [2]. Although S. aureus is often associated with antimicrobial drug resistance, large outbreaks of S. aureus predate the advent of widespread resistance. Methicillin resistance, conferred by a large transmissible staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), first emerged in 1961 and for the first 30 years became endemic as hospital-associated (HA)-MRSA affecting patients with underlying comorbidities or exposure to the health-care setting [3]. The earliest reported MRSA infections acquired from the community date back to the 1980s when outbreaks of invasive infections occurred in intravenous drug users in Detroit [4, 5]. Nearly in parallel, first reports of MRSA infections acquired from the community emerged from indigenous populations in remote areas in Western Australia [6]. These strains initially were genetically diverse and distinct from other clones circulating in Australia. By the late 1990s, MRSA infections acquired from the community were recognized as a distinct clinical entity [7] owing to their emergence among young and healthy individuals without the traditional healthcare risk factors as well as their distinct genetic background and relatively preserved antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. However, the epidemiology and definition of these community-associated (CA)- and HA-MRSA are evolving as CA-MRSA lineages are increasingly invading the healthcare system, contributing to nosocomial infections [8, 9], and accumulating greater drug resistance. This case series aims to highlight recent insights into the global molecular epidemiology of community- associated S. aureus and in particular MRSA infections.

2 Methods

The definition of what constitutes CA-MRSA remains poorly delineated. This term has been used interchangeably to indicate the source of the infection, the S. aureus genotype and antibiotic phenotype. “Classical” CA-MRSA presents as community-onset, retains susceptibility to non-β-lactam antibiotics, harbors smaller SCCmec cassettes IV and V and frequently carries the lukSF-PV genes, encoding for the Panton–Valentine leukocidin toxin (PVL). Although several definitions for CA-MRSA have been proposed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of CA-MRSA is the most widely used (see below).

2.1 CDC Definition of CA-MRSA Infection

Positive culture for MRSA as an outpatient or within 48 h of hospital admission.

No medical devices or indwelling catheters that are permanently placed though the skin.

No history of MRSA infections.

No recent history of hospitalization or residence in nursing home or long-term care facility.

For the purpose of this case series we will use this epidemiological definition of CA-MRSA and consider it as a unique disease entity. Although HA-MRSA strains are rarely transmitted in the community, genetic lineages of CA-MRSA have penetrated into the healthcare system making a distinction of CA- and HA-MRSA based on genotype obsolete. Nevertheless, recognition of the unique genetic features of these lineages is important in understanding some of the clinical properties and antibiotic phenotypes for optimizing treatment and preventive efforts. An additional limitation in comparing molecular epidemiology studies on CA-MRSA is the wide variety of genotyping techniques and epidemiological definitions that are being used. For example, several groups have used genotypic methods only to identify CA-MRSA, in particular by employing the presence of SCCmec types IV or V as a signature for CA-MRSA. However, the utility of this method relies on the strict association of CA-MRSA and SCCmec types IV and V, which in light of the changing epidemiology of CA-MRSA in many cases is not a reliable assumption anymore.

For the purpose of this review we have used MLST results as the primary mode of describing S. aureus clones and comparing them between studies. We have added additional genotyping information, as it was available or relevant. The most commonly used genotyping techniques include:

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [10]

Sequencing of internal fragments of specific housekeeping genes.

Seven gene loci are compared in S. aureus—carbamate kinase (arcC), shikimate dehydrogenase (aroE), glycerol kinase (glpF), guanylate kinase (gmk), phosphate acetyltransferase (pta), triosephosphate isomerase (tpi), and acetyl coenzyme A acetyltransferase (yqiL).

Sequence differences in each gene are considered alleles and the seven gene loci create an allelic profile by which the sequence type is determined.

Pulse Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) [10]

Genomic DNA isolated from S. aureus is digested by SmaI and run through a gel matrix by alternating electric currents.

Banding pattern created is based on size of each fragment.

Banding pattern is compared to reference strains to determine PFGE type.

Spa-typing [10]

Highly polymorphic staphylococcal protein A (spa) is amplified and sequenced.

Sequencing of single gene locus is more efficient and cost-effective than MLST.

Ridom SpaServer (http://spaserver.ridom.de) and eGenomics (http://www.egenomics.com) are used to compare sequence and number of repeats.

SCCmec typing [11]

The mec gene encoding methicillin resistance is found within a mobile genetic element called staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec).

SCCmec elements are typed I–XI based on structural organization and genetic content, particularly the sequence of the mec and ccr gene complexes.

SCCmec subtypes are based on variation in regions other than the mec and ccr gene complexes.

HA-MRSA traditionally carries SCCmec types I, II, or III, while CA-MRSA was initially characterized by SCCmec type IV and V.

International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome (http://www.sccmec.org).

3 Case Studies

3.1 An Outbreak of CA-MRSA Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in the USA

From August to September 2003, an outbreak of USA300 community-associated MRSA causing SSTIs was documented amongst a California collegiate football team [15]. 11 members from a team of 107 players presented almost exclusively with a boil on their elbows during the start-of-season training camp, a 2-week period of rigorous physical activity when many players lived in close proximity. During the preceding season in 2002, two players had already encountered USA300 CA-MRSA SSTIs. To identify the source of these infections, 99 players were screened for S. aureus nasal carriage, and 8 (8 %) of the players were colonized with MRSA. One of these MRSA carriers was previously infected, occupied the locker directly across from the index case of the 2003 outbreak, and shared a room with another case during the training camp. The clustering of cases and carriers by locker room assignments was also more generally observed. Multivariate analysis identified the sharing of soap and towels as a significant risk factor for both CA-MRSA infection and carriage. Four MRSA isolates from culture confirmed cases were analyzed by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). These PFGE patterns were identical to each other, the two 2002 season SSTI cases, and the USA300 strain isolated from other SSTI outbreaks in Los Angeles County. Despite the implementation of numerous infection control measures, including hexachlorophene showers, decolonization efforts, and hygiene education, an additional outbreak of four SSTI cases occurred from October to November 2003 and a single recurrent case occurred during the 2004 season. Tracking the incidence of CA-MRSA SSTI in this college football team from 2002 to 2004 illustrates the high rate of recurrence at the individual and group level and the difficulty of eradication in the athletic setting.

3.1.1 Current Characteristics and Global Burden of CA-MRSA SSTIs

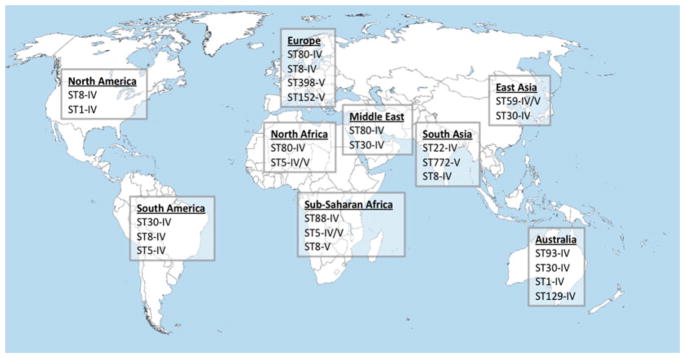

This case highlights a number of unique features of CA-MRSA, in particular the frequent presentation as SSTIs, the potential for recurrent infections, the role of close physical contact and contaminated objects as well as the propensity to cause outbreaks among young and healthy athletes. Initially, CA-MRSA was mainly recognized during outbreaks and was found to disproportionally involve athletes [12–15], military personnel [16], prisoners [16], children in day-care centers [17], indigenous populations [18], and Pacific Islanders [19]. Since their initial recognition, polygenetic lineages of CA-MRSA have become endemic in communities worldwide (Fig. 1) and mainly contribute to an epidemic of SSTIs, but invasive disease with unfavorable outcomes occur in a substantial number of cases. It is difficult to estimate the current global burden of CA-MRSA in part because studies on the prevalence of MRSA from many parts of the world are still lacking [20]. Nevertheless, based on currently available data, 5 of about 20 distinct genetic lineages are globally prevalent, including ST1-IV (WA-1, USA400), ST8-IV (USA300), ST30-IV (South West Pacific clone), ST59-IV/V/VT (USA1000, Taiwan clone), and ST80-IV (European clone). In particular ST8-IV and ST30-IV have been relatively frequently reported from every continent and can be considered pandemic clones [21]. This co-emergence of multiple CA-MRSA lineages is striking and no single genetic or epidemiological factor has been identified that accounts for the extraordinary success of some genetically distinct clones. However, it has been generally accepted that the smaller SCCmec cassettes IV and V that are typically seen in CA-MRSA may provide a fitness advantage based on their increased growth rate compared to the larger elements I–III seen in traditional HA-MRSA lineages [22].

Fig. 1.

Global distribution of major CA-MRSA lineages by multi-locus sequence typing

3.1.2 USA300: Prototype of CA-MRSA

In general, it appears that the USA carries some of the highest burden of CA-MRSA conferred by a single clone, whereas Europe has a lower prevalence and a higher genetic diversity of CA-MRSA [20]. The initial wave of CA-MRSA in the USA was attributed to USA400 (MW2), which was rapidly replaced by a seemingly unrelated clone, PFGE-type USA300-ST8-SCCmecIV. In 2005, based on data from San Francisco, it was estimated that ~90 % of all MRSA infections were community-associated with USA300 predominating [23]. Since, this single clone has accounted for the majority of all CA-MRSA infections in the 48 contiguous states of the USA. USA300 is currently the single most widely reported CA-MRSA clone and has been described from every continent except Antarctica [24]. CA-MRSA, in particular USA300, has been the most common cause of SSTIs in urban emergency departments in the USA over the past few years [25, 26]. These CA-MRSA infections precipitate a significant economic burden on the individual and societal level [27].

The basis for this tremendous success remains only partially understood. On the basis of CA-MRSA outbreak data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed a conceptual model incorporating epidemiological risk factors. This “Five Cs of CA-MRSA Transmission” model suggests that MRSA infection results from: (1) Contact, direct skin to skin; (2) lack of Cleanliness; (3) Compromised skin integrity; (4) Contaminated object surfaces and items; and (5) Crowded living conditions [28].

Observational research has also recognized the household as a potentially important transmission setting for S. aureus. Several reports document the spread of CA-MRSA within households and the potential for these strains to “ping pong” and cause recurrent infections among family members [29]. Close personal contact with household members who have a skin infection may also increase the risk of transmission and young children appear to be particularly important as reservoirs and potential vectors for CA-MRSA [30, 31]. Several studies have also commented on the increase in nasal and extra-nasal colonization with CA-MRSA strains [32] and the potential of household surfaces as sources for transmission or of recurrent infections [28, 30, 33]. However, in many cases, including outbreak (epidemic) and non-outbreak (endemic) CA-MRSA, it is often impossible to identify an endogenous source of the infection, such as nasal colonization, despite the increased risk for subsequent infection in nasal carriers.

The resolution of the whole genome sequence of USA300 revealed five large genetic elements on the chromosome and three plasmids [34]. USA300 contains SCCmecIVa, the arginine catabolic mobile genetic element (ACME), a novel pathogenicity island SAPi5 encoding two enterotoxins Seq and Sek as well as prophages ϕSA2usa (encoding PVL) and ϕSA3usa containing staphylokinase and chemotaxis-inhibiting protein. ACME is present in about 85 % of USA300 isolates. Recently, it has been found that the spermidine acetyltransferase gene (speG) may play a major role in protecting USA300 from polyamines, which S. aureus in general is very susceptible to [35]. This could explain in part the apparently increased colonization and transmission capacities of USA300.

3.1.3 Putative Virulence Factors of CA-MRSA

At the beginning of the CA-MRSA epidemic, a strong relationship was noted between the presence of bacteriophage encoded cytolytic toxin PVL and the observed clinical virulence of the strains, in particular its association with furunculosis, a type of skin infection [36]. Moreover, this bi-component toxin, encoded by the lukS and lukF genes, was generally absent from traditional HA-MRSA [36]. However, CA-MRSA clones that lack PVL and remain comparably virulent have been observed, and isogenic PVL gene deletion mutants lacked a substantial shift in virulence in animal models [37]. Investigations have been hampered by the fact that PVL only lyses neutrophils of humans and rabbits, but not those of many other common animal models [38]. Studies in rabbit infection models have suggested that PVL may contribute significantly to particular types of infections, such as severe lung infections and osteomyelitis [38–41]. However, in a rabbit skin infection model, PVL was not found to contribute to the virulence of USA300, whereas α-toxin, phenol-soluble modulin-alpha peptides (PSMα), and accessory gene regulator (Agr) did [42]. In light of these differences, the debate continues about the exact role of PVL in the CA-MRSA epidemic.

Therefore, PSM or core-genome virulence factors such as α-toxin have been implicated in the documented increased virulence of CA-MRSA compared to HA-MRSA [37, 42–44]. The α-toxin significantly contributes to CA-MRSA virulence in the skin and lung infection models [42, 43]. Furthermore, a core-genome encoded toxin, SEIX, contributed to lethality in a necrotizing pneumonia model [45]. PSMs are small cytolytic peptides that appear to express much stronger in CA-MRSA than in HA-MRSA [37]. A variant, PSM-mec, is encoded on select SCCmec elements and when present contributes significantly to S. aureus virulence [46]. In addition, the activity of the global regulator Agr, contributes to expression of toxins [47].

3.2 A Case of CA-MRSA Necrotizing Pneumonia from Australia

A 23-year-old woman presented to an emergency department with acute radicular lower back pain and was discharged despite tachycardia and fever [48]. 2 days later, she presented again with continued back pain, shortness of breath, vomiting, myalgia, fever, sweating, dry cough, and anterior pleuritic chest pain. The patient was noted to have an erythematous lesion on her left elbow and a family history of recurrent furunculosis. Upon admission to the hospital, she was again tachycardic and febrile but also hypotensive and tachypnic requiring a non-rebreather. Her exam was notable for a furuncle on her left elbow, midline and left paraspinal tenderness over T8/9, as well as tenderness in the right upper quadrant of her abdomen. Blood work showed a predominantly neutrophilic leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, renal dysfunction, an elevated creatinine level, and her chest X-ray showed bilateral multilobar consolidation. Her initial treatment included empirical IV antibiotics (ticarcillin/clavulanate, gentamicin, and azithromycin), fluid resuscitation, a noradrenaline infusion, and IV hydrocortisone, and subsequently also 2 g dicloxacillin. 6 h after admission, the patient’s respiratory status deteriorated and precipitated intubation and mechanical ventilation. Circulatory deterioration continued despite the addition of activated protein C and vasopressin and high-dose noradrenaline and adrenaline infusions. 14 h after admission, Staphylococcus was identified in an initial blood culture, and IV vancomycin 1,000 mg was added. At 16 h after admission, the patient first went into ventricular tachycardia and despite attempts of resuscitation the patient died 1 h later. Thereafter, blood cultures, endotracheal aspirates, and furuncle swabs and biopsies all returned positive for MRSA. The MRSA isolates were sensitive to multiple antibiotics, including erythromycin, clindamycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin. All isolates were Panton–Valentine Leukocidin positive and resembled ST93-IV (“Queensland clone”) CA-MRSA. Subsequently, nasal swabs collected from three family members, including two who suffered from recurrent furunculosis, were also positive for the Queensland clone CA-MRSA.

3.2.1 Burden of CA-MRSA in Australia

CA-MRSA became endemic in Northern Australian indigenous communities in the 1990s and was caused by a remarkable diversity of genetic backgrounds. These included the pandemic CC1, CC5, CC45, and CC8 backgrounds as well as the smaller CC298 lineage [49]. Notably, all but one of these CCs was PVL negative. Since then, the molecular landscape of S. aureus infections across the country has changed considerably. Based on national surveys of CA-S. aureus infections since 2000 a steady increase in CA-MRSA from 6.6 % in 2000 to 11.5 % in 2010 has been documented, which was mainly accounted for by the emergence of ST93-IV PVL+[50]. In 2010, this strain constituted 41 % of all CA-MRSA, 28 % of all MRSA and 4.9 % of all S. aureus community-onset infections [51]. In addition, many diverse types contribute to CA-MRSA, including ST1-IV-PVL-negative (WA-1) and South West Pacific ST30-IV-PVL-positive, which account for about 15 % of CA-MRSA each, whereas the multidrug resistant ST239-III still dominates as the most common HA-MRSA strain in Australia [52]. International CA-MRSA lineages such as PVL-positive ST30-IV, ST8-IV, ST59-IV, ST80-IV, and ST772-V (Bengal Bay) have also increased in prevalence [53]. For example, USA300-like West Australian (WA) MRSA-12 clone was noted in the area near Perth and by a combination of MLST, PFGE, and PVL-typing as well as by prevalence of ACME [33], found to be indistinguishable from the North American USA300 [54].

Infections with ST93-MRSA predominantly manifest as SSTI, but an enhanced clinical virulence as evidenced by reports of severe invasive infection such as necrotizing pneumonia, deep-seated abscess, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and septicemia has also been suggested [48, 52]. ST93 has now also been described in New Zealand and the UK and many of these cases could be epidemiologically linked to Australia [55].

ST93 initially carried few antibiotic resistance determinants except for ermC, which was identified in several early MSSA and MRSA (parallel to USA300). More recently, additional resistance determinants such as msr(A) and tetK have been reported in some ST93 isolates [50].

By MLST analysis ST93, most frequently associated with SCCmec IV (2B) and PVL positive, represents a singleton and is distinct from other S. aureus clones and unlikely related to the early Australian CA-MRSA clones. However, a high prevalence of ST93 MSSA carrying PVL was noted in studies in Aboriginal communities in the 1990s, giving rise to the idea that these isolates may have served as the direct precursor [56]. It has been suggest that the overall heavy burden of MRSA and MSSA in Aboriginal communities in Northern Australia, which includes a phylogenetically distinct lineage ST75 [57], may continue to give rise to novel MRSA clones [58].

As with USA300 the apparent increased virulence of ST93 in its clinical presentation is mirrored in increasing virulence in a model system, namely, the wax moth larvae and mouse skin in vivo models [59]. In the latter, ST93 was even more virulent than USA300 [59]. Based on whole-genome sequencing, both strains contain α-hemolysin, PVL, and α-type phenol soluble modulins but no overt novel virulence determinant has been identified in ST93. This suggests changes in gene expression or subtle genetic alterations.

3.3 The Invasion of CA-MRSA into the Healthcare Setting

In 2006, a 46-year-old male presented to an emergency department with severe lower abdominal pain, fever, and chills [60]. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus, end-stage liver disease due to hepatitis C infection, and benign prostatic hypertrophy and had been admitted 3 weeks prior to a different hospital for a urinary tract infection. This infection was treated with intravenous cipro-floxacin and vancomycin as well as an indwelling Foley catheter. In the emergency department, the patient was again diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and acute renal failure, admitted to the hospital and treatment with empirical levofloxacin and vancomycin was initiated. 2 days after presentation, blood and urine cultures revealed the presence of MRSA and further workup revealed a 2 cm vegetation on the non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve, consistent with MRSA endocarditis. Despite continued vancomycin treatment, MRSA was still recovered from blood cultures on days 7, 10, and 11 after presentation. These isolates were susceptible to chloramphenicol, clindamycin, daptomycin, gentamicin, linezolid, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. They were also intermediate to levofloxacin and had a vancomycin MIC of 1 μg/ml. On day 12, antibiotic therapy was switched from vancomycin to daptomycin due to worsening renal failure. The patient was transferred to the original hospital for cardiovascular surgery on day 18, and MRSA with an intermediate resistance to vancomycin (MIC = 8 μg/ml) and non-susceptible to daptomycin (increased MIC from ≤0.5 to 4 μg/ml) were identified in cultures from day 19. 20 days after his presentation, the patient died. Molecular typing revealed that he had been infected with a PFGE-type USA300 strain carrying the SCCmec IVa element and the PVL gene. This case illustrates a patient with traditional risk factors for HA-MRSA being infected with a prototype of CA-MRSA as well as the ability to develop glycopeptide resistance in CA-MRSA isolates.

3.3.1 CA-MRSA and Nosocomial Infections

One of the early defining features of the CA-MRSA epidemic was the lack of traditional nosocomial risk factors in affected patients. Since, nosocomial outbreaks of CA-MRSA strains have been observed in numerous countries around the world, including Australia, the UK, the USA, Japan, Israel, and Italy [61–67], as well as the establishment of CA-MRSA genotypes as primary hospital-associated infections [9, 68].

Only shortly after the recognition of CA-MRSA in Australia, the first report of a single-strain outbreak with EMRSA-WA95/1 in an urban Western Australian hospital occurred in the mid-1990s [61]. The two index patients originated from a remote region of Western Australia. A subsequent analysis of S. aureus carriage examining multiple body sites revealed a high prevalence of MRSA colonization in their two communities (39 and 17 %) with isolates that were indistinguishable from the outbreak strain by molecular typing [61]. As in this case most of the reported nosocomial CA-MRSA outbreaks have only involved a small number of patients. To date the apparently largest documented outbreak involved the spread of ST22-PVL + and ST80-PVL + in 10 healthcare institutes in southern Germany. This resulted in 75 cases, including 52 patients, 21 healthcare workers, and 2 private contacts [66].

Many of the reported nosocomial CA-MRSA outbreaks have been related to neonatal or maternity units, such as in New York City with two outbreaks of MW2/USA400-IV-PVL+ [62, 63], in the UK with Australian WA-MRSA-1 (ST1-IV-PVL-) [64] and ST30-IVc-PVL + involving several Filipino healthcare workers [65], in Israel in a neonatal ICU with ST45-PVL - [67], and in Italy related to USA300 [69]. These occurrences frequently involved asymptomatic colonization of either close family contacts or healthcare workers.

Nosocomial outbreaks with USA300 were also encountered in Japan [70, 71]. However, already early on in the USA300 epidemic there was evidence that this clone rapidly started to contribute to the burden of MRSA in the hospital setting [23]. More recently, USA300 was found to account for 28 % of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections (contact with healthcare facility within year prior to admission) and 20 % of nosocomial infections (positive blood culture more than 48 h after admission)[9]. In parallel, an increase in colonization with strains consistent with USA300 was also noted in pediatric ICU patients from 2001 to 2009, where in 2009 36 % colonization isolates had a spa-type consistent with USA300 and 29 % of isolates were PVL positive [72].

Likewise, other CA-MRSA such as ST93 and ST30 in Australia are now more likely to be acquired in the hospital than in the community [68]. This remarkable success of USA300 and other CA-MRSA strains also in the hospital setting is contrasted by investigations that have suggested that CA-MRSA might be less successful than HA-MRSA in the hospital environment because of their generally higher susceptibility to a variety of antibiotics [73]. In a comparison of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA transmission in four Danish hospitals, the nosocomial transmission rate of HA-MRSA was estimated to be 9.3 times higher than for CA-MRSA (defined as USA300-ST8, the SW Pacific clone ST30, USA400, and the European clone ST80). All other genotypes were classified as HA-MRSA [73]. In addition, in some instances CA-MRSA clones present in the general population may be less capable of infiltrating the healthcare environment as shown in a Spanish pediatric hospital [74].

However, as CA-MRSA clones have spread and diversified, we have seen a steady rise in antibiotic resistance among CA-MRSA isolates [26, 50], which may in part account for their increasing resilience in the hospital setting. In that context, the occurrence of a decreased susceptibility to vancomycin in USA300 isolates is not surprising [72, 75], but the prospect of multidrug resistance in strains with increased virulence is a source of great concern.

3.4 CA-MRSA and Travel

In March 2006, a 47-year-old Caucasian man presented to a dermatology outpatient unit in Switzerland [76]. The patient had recently returned from a 1-week scuba diving trip in the Philippines (Bohol Island and Negros Island), and two skin abscesses were noted on the patient’s right forearm. Upon returning from the trip, the patient had noticed two insect bite-like lesions on his right forearm. Within 2 days, the lesions were red and itchy. Despite the use of corticoid treatment, the lesions progressed to become abscesses and were accompanied by edema of the forearm and the back of the hand. He was prescribed topical fucidin cream and oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid therapy, but the abscesses continued to worsen. The larger abscess measured 2 cm in diameter, and green-yellowish discharge was observed. No fever, adenopathy, or other symptoms were documented. Upon presentation, a PVL-positive ST30 CA-MRSA with resistance only to -lactam antibiotics was recovered. Following hospitalization, the abscesses were drained and a 5-day course of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and topical mupirocin and ichthammol was commenced. The lesions began to resolve within a few days. ST30, also known as the South West Pacific clone, is a prominent CA-MRSA clone in the Philippines and is very rarely found in Switzerland, supporting the Philippines as the origin of this infection. The combination of minor skin abrasions from the patient’s scuba diving activities and exposure to a local CA-MRSA clone resulted in deep-seated abscesses requiring hospitalization and drainage.

3.4.1 International Molecular Epidemiology

A number of studies have directly or indirectly documented that returning international travelers with MRSA infections have contracted strains specific to their country of vacation [77–79]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that PVL + MSSA, often detected at high frequency in parts of Africa, may have acted as a reservoir for CA-MRSA [80, 81]. The emergence of methicillin-resistance is to not exclusively linked PVL-positive MSSA as for example USA300 appears to have evolved from a USA500 progenitor where the acquisition of PVL was one of the last steps in this process [82]. Nevertheless, the high frequency of pandemic lineages associated with MRSA in Africa is striking, but relatively little is known about the S. aureus population structure as most S. aureus molecular epidemiology studies were carried out in the USA, Australia (both discussed above), and Europe. In general, it is considered that Europe has a lesser burden of CA-MRSA than the USA with perhaps the exception of Greece [83]. A variety of international S. aureus strains are present, which mainly include ST80, ST1, ST8, ST30, and ST59 on the continent as well as ST93 in England. In addition, sporadic ST152 MRSA isolates have been recovered in Central Europe, the Balkan, Switzerland and Denmark and it has also been speculated that these may have derived from African ST152 MSSA strains [84]. Previously, ST80 (European clone) was predominant, but now USA300 is also emerging as major clone [83]. The European MRSA epidemiology was recently reviewed by Otter and French and will not be further discussed here [83].

The following section aims to highlight recent advances on the burden and molecular epidemiology of S. aureus in Asia, Africa, Middle East, and Latin America. In light of the paucity of data from some more remote parts of the world, a number of studies were included that lacked detailed genotyping, but that nevertheless provide valuable information in estimating the burden of MRSA in select remote geographic regions (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Molecular epidemiology of S. aureus infections in diverse geographic regions

| Region | Year | Source and Population | Number Patients | Number S. aureus | CA-MRSA (% of MRSA) | Molecular typing | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| MSSA | MRSA (%) | |||||||

| Africa | ||||||||

| African towns [98] Cameroon Morocco Niger Senegal Madagascar |

2007–2008 | Clinically suspected S. aureus infections at five African tertiary care centers | 542/555 isolates | 469 | 86 (15 %) | 9 (10.5 %) by epidemiology | MRSA: ST239/241 (40 %), ST88 (28 %), ST5 (21 %); also ST8, ST30, ST1289; 20 (23 % of MRSA) PVL+ CA-MRSA (%): ST88 [45], ST5 [45], ST8 [10], all SCCmecIV |

Overall low prevalence of MRSA and minimal evidence for significant CA-MRSA |

|

| ||||||||

| Tunisia [95] | 2000–2009 | Case series of invasive CA-MRSA |

14 | N.A. | 14 (100 %) | All | None | Increasing CA-MRSA |

|

| ||||||||

| Tunisia [124, 125] | 2003–2005 | Outpatients mainly with SSTIs | 64 | N.A. | 64 (100 %) | All | All ST80-IV-t044-PVL+ Some minor variation on PFGE |

Single clone with low drug resistance |

| Algeria [96] | 2003–2004 | Inpatients and Outpatients | 614 | 410 | 204 (33 %) | Unknown | 61 MRSA selected (20 CA-MRSA) ST80 most common in HA- and CA-MRSA; also ST5 | PVL+72 %, multidrug resistance |

| Egypt [97] | 2007–2008 | Private clinic Zagazug City, all sites | 21 | N.A. | 21 (100 %) | 4 (19 %) by epidemiology | CA-MRSA (n=4): ST80, ST30, ST1010, all PVL+ | ST80 distinct to European ST80 as tetracycline, fusidic acid sensitive |

| Nigeria | ||||||||

| South West [103] | 2005 | Clinical | 276 | 273 | 4 (1.4 %) | Unknown | 45 PFGE types, 9 wide spread, major type = 23 % MRSA: 3/4 ST8 |

Rare MRSA, no evidence for CA-MRSA |

| South West [104] | 2007 | Patients admitted to two hospitals (70 % wounds, 21 % ENT) | 1,300/346 aureus | S. 276 | 70 (20 %) | 33 (47 %) by epidemiology | MSSA: ST5 (28 %), ST7 (16 %), ST121 (13 %), ST30 (11 %), ST8 (9 %), other ST1, ST15, ST508, ST80, ST25, ST72 MRSA: ST88-IV (47 %); ST241-IV (10 %), ST250-I (43 %) |

CA-MRSA (all ST88) with ophthalmologic and auricular infections |

| South West [126] | Before 2012 | Tertiary hospital patients | 116 | 68 | 48 (41 %) | 8 (17 %) by PBP4 typing | No clonal typing 28 (41 %) of MSSA PVL+ All MRSA PVL- |

Low prevalence of CA-MRSA |

| South West and North East [127] | 2009 | Hospital infections Student carriage |

60 8 |

49 8 |

11 (16 %) 0 (0 %) |

Unknown | MSSA: CC15 (32 %), CC8 (14 %), CC30 (5 %), CC121 (14 %), CC5, CC1; PVL+40 % MRSA: ST241-III-t037 (55 %), ST8-V-t064/t451 (27 %), ST94- IV-t008 (CC8), ST5- V-t002, all PVL- |

High resistance to tetracycline, cotrimoxazole (70 %) |

| North East [84] | 2007 | Clinical specimens six tertiary care hospitals | 96 | 84 | 12 (13 %) | Unknown | All MRSA ST241-III-PVL- Diverse MSSA, ST152 (19 %), CC8 (25 %), CC121 (13 %), CC1 (13 %), one isolate (6 %) each: CC5, CC9, CC15, CC30, CC80 |

No evidence for CA-MRSA Most ST152 MSSA PVL+ |

| Togo, Lome [128] | 2003–2005 | Outpatients with SSTIs | 84 | 54 | 30 (36 %) | All | None | 42 % with impetigo |

| Gabon [105] | 2009–2010 | Patients with SSTIs (31), bacter-emia (11) | 58 | 52 | 6 (11 %) | Unknown | MSSA: ST15 (33 %), ST88 (17 %), ST1 (15 %), ST152 (12 %), <10 %: ST5, ST8, ST1746 MRSA (n=6): all ST88 |

57.4 % PVL+ |

|

| ||||||||

| South Africa | ||||||||

| South Africa [109] | 2005–2006 | Nationwide survey of invasive and non-invasive MRSA | 320 | N.A. | 320 (100 %) | Unknown | 31 PFGE types and 31 spa types, spaCC64- IV-ST612 (25 %) spa-CC12-II-ST36 (24 %), spa-CC37- III-ST239 (21 %), t045-I-ST5 | First MRSA national surveillance |

| Capetown [108] | 2007–2008 | MRSA from five city hospitals | 100 | N.A. | 100 (100 %) | 10 (10 %) by epidemiology |

ST612-MRSA-IV (CC8, 40 %) ST5-MRSA-I (37 %) ST239-MRSA-III ST36-MRSA-II |

ST612 with multidrug resistance |

| Middle East | ||||||||

| Israel [129] | 2006–2009 | National survey, five general hospitals | 315 | N.A. | 315 (100 %) | 160 (51 %) by epidemiology | Mostly t001-I (31 %), t002-II (26 %), t008-IV (7 %) SCCmec IV and V among HA-MRSA |

~50 % invasive and wound infections |

| Lebanon [130] | 2006–2007 | Random selection of S. aureus isolates from inpatients and outpatients | 130 | 37 | 93 (75 %) | Not defined | MRSA: t044-ST80-IVc- PVL+(38 %), ST30-IVc, ST97-V, ST8-IVc, ST6-IVc, ST22-IVc, ST5-IVc, ST239-III; PVL+62 % MSSA: ST5, ST30, ST121, ST1, ST80; PVL + 20 % |

SSTIs due to ST80 |

| Kuwait [114, 131] | 2001–2003 | National survey from seven hospitals | 1,457 | 1,381 | 76 (5.2 %) | 26 (34 %) by SCCmec type | MRSA: ST80-IV (26 %), ST30-IV (31 %), also ST8-IV, ST5-IV, ST728-IV; PVL+77 % | |

| Kuwait [132] | 2005 | Surveillance of 13 hospitals with 1,765 inpatients and 81 outpatients | 1,846 | 1,258 | 588 (32 %) | 101 (17 %) by SCCmec type and non-MDR phenotype | No clonal typing | Stable MRSA prevalence; possible increase in CA-MRSA |

|

| ||||||||

| Iran | ||||||||

| Tehran [133] | 2004–2005 | Hospital | 277 | 178 | 99 (36 %) | 2 (2 %) by SCCmec typing | Only 2 % carried SCCmec IV 98 % SCCmec III | SCCmec III isolates MDR |

| Tehran [134] | 2009 | Teaching hospital | 140 | N.A. | 140 (100 %) | Unknown | Five PFGE types: ST239 (82 %), ST1238 (15 %), ST8 (1 %) | No evidence for CA-MRSA |

| Isfahan [115] | 2010 | Hospital, consecutive S. aureus infections | 83 | 66 | 17 (20 %) | 2 (12 %) 17 (26 %) CA-MSSA |

MRSA: ST15, ST25, ST239 (41 %), ST291, ST859 MSSA: Majority (76 %) due to ST8, ST22, ST30, ST6 |

No significant evidence for CA-MRSA, ST8-MSSA-PVL as HA-SA |

| Saudi Arabia [135] | 2010–2011 | Tertiary care hospital | 107 | N.R. | 107 (100 %) | Unknown | High diversity of MRSA, ST239-III (21 %), CC22-IV (28 %), CC80-IV (18 %), CC30-IV (12 %) | 54 % PVL+ |

| Bahrain [136] | 2005 | Diverse MRSA isolates | 53 | N.A. | 53 (100 %) | 7 (13.3 %) by SCCmec type | No clonal typing 13.3 % SCCmec IV (5/7 PVL+) 87 % SCCmec III |

SCCmec III isolates were MDR |

|

| ||||||||

| Latin America | ||||||||

| Cuba [137] | 2008 | Putative MRSA from three hospitals and national reference center | 68 | 28 | 40 (59 %) | Unknown | MRSA: spa t149 (60 %, historically ST5), t008 (20 %), t037 (15 %), t4088, t2029 All t008 PVL+ |

41 % discrepancy between phenotyping and genotyping (mecA) |

| Martinique, Dominican Republic [79] | 2007–2008 | Reference laboratory DR | 112 | 90 | 22 (20 %) | Unknown | MSSA: ST30 (33 %), ST5 (8 %), ST398 (8 %), ST8 MRSA: ST72 (23 %), ST30 (27 %), ST5 (18 %) |

MRSA 80 % with SCCmecIVa |

| Hospital outpatients MQ | 143 | 87 | 56 (39 %) | Unknown | MSSA: diverse; ST152 (15 %), ST398 (10 %), ST5 MRSA: ST8-IVc-t304 (80 %) |

Older patients, possible HA-MRSA | ||

| Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela [138] | 2006–2008 | 32 tertiary care hospitals, consecutive isolates | 1,570 | 926 | 644 (41 %) Peru 62 %, Colombia 45 %, Ecuador 28 %, Venezuela 17 % | 174 (27 %) by PFGE, SCCmec, PVL genotyping | MRSA: ST8-IVc- ACME -(21 %), ST5-variant, ST6, ST22, ST923 SCCmecIVc isolates with 41 % tetracycline resistance |

CA-MRSA USA300 variant established in South America, including as HA-MRSA |

| Uruguay [139] | 2002–2003 | Inpatient and outpatient at two hospital centers, mainly SSTIs | 125 | N.A. | 125 (100 %) | 97 (78 %) by epidemiology | Analysis of 68 isolates: PFGE-A/ST30-IVc- PVL + (75 %), ST5, ST72, ST97, ST1, ST45 | Outbreak “Uruguay clone” |

| Uruguay [140] | 2004–2005 | Outpatients SSTI | 213 | 123 | 90 (42 %) | 90 (42 %) by epidemiology | MRSA: six PFGE types, 90 % “Uruguay clone”, 96 % PVL+ | Possible outbreak |

| Argentina [117] | 2005, 2006 | S. aureus inpatients and outpatients in 14 hospitals | 376 | 220 | 156 (41 %) | 22 (6 %) by epidemiology |

ST5 (89 % in CA-MRSA), mainly t311, SCCmec IVa, PVL+; low prevalence ST917/CC8, ST100, ST918 CA-MSSA: ST5, ST8, ST30 |

Low frequency of CA-MRSA (16 % of CA-SA), more in children with SSTI |

| Colombia, Bogota [141] | 2009–2011 | Clinical infections 15 hospitals | 154 | N.A. | 154 (100 %) | 154 (100 %) by SCCmec | ST8-IVc-PVL+, ACME-(90 %), ST8- IVa-t1635 (5.2 %), also ST923 | Emergence of new CA-MRSA clone |

| Columbia, Medellin [142] | 2008–2010 | Three tertiary care hospitals | 538 | N.A. | 538 (100 %) | 68 (13 %) by epidemiology 243 (45 %) HA-community onset |

ST8-MRSA-IVc (55 %, spa t1610, t008, t024), ST5-MRSA-I (32 %) SCCmec-IVc in 92 % of CA-MRSA |

CA-MRSA genotypes circulating in hospitals, Tetracycline resistance (46 %) in ST8 |

|

| ||||||||

| Asia | ||||||||

| Malaysia [143] | 2006–2007 | Invasive isolates from a large public hospital | 36 | N.A. | 36 (100 %) | 2 (5.6 %) by epidemiology | ST239-MRSA-III t037 (83 %), SCCmecV PVL + in on each ST772 and ST1 | No significant CA-MRSA |

| Malaysia [144, 145] | 2007–2008 | Tertiary hospital in Kuala Lumpur | 4,280 | 2,393 | 1,887 (44 %) | 21/389 (5.3 %) by genotyping | MRSA (389 genotyped): ST239-MRSA-III (92.5 %), ST1, ST188, ST22, ST7, ST1283 CA-MRSA (n=21): ST188-V-PVL+(38 %), ST1-V-PVL+(43 %), ST7-V (19 %) |

ST239 isolates all MDR |

| Malaysia [146] | 2002–2007 | Sensitive MRSA in hospital | 13 (nine analyzed) | N.A. | 13 | 2 (15 %) by epidemiology | HA-MRSA (n=11): ST6, ST30, ST22, ST1179 CA-MRSA (n=2): ST6, ST30 All SCCmec IV |

Not MDR 7/9 SSTI |

| Malaysia [147] | 2006–2008 | Survey of MRSAs from nine hospitals | 628 | N.A. | 628 | 9 (1.4 %) by epidemiology | CA-MRSA: ST30- PVL+(89 %), ST80-PVL-(11 %) HA-MRSA: Diverse ST30 (18 %), 1 each: ST45, ST188, ST22, ST101, ST1284-1288 |

Nine HA-MRSA with SCCmecIV All CA-MRSA were SSTIs |

| China | ||||||||

| Wenzhou [86] | 2002–2008 | SSTIs at a teaching hospital | 111 | 51 | 60 (54 %) | 48 (43 %) CA-SA (MSSA and MRSA) | 32 PFGE types, MRSA mainly ST239-III (32 %), ST1018-III (17 %), ST88 (10 %) CA-SA: ST1018 MRSA (15 %); 8 % each: ST88, ST188, ST239 |

ST239 and ST1018 spread between community and hospital |

| Beijing [148] | 2003–2007 | Impetigo cases at children’s hospital | 984 of 1,263 cases | 973 | 11 (1.1 %) | 11 (1 %) by SCCmec-typing | No clonal typing SCCmecIV-PVL+54 % |

CA-MRSA uncommon |

| Beijing [149] | 2009–2010 | SSTIs at four Beijing hospitals | 164 of 501 cases | 159 | 5 (3 %) | 5 (3 %) | MSSA: ST398 PVL+(17 %), ST7 (12 %), ST1 (7 %), ST59, ST5, ST6 MRSA (n=5): ST6, ST8, ST59, ST239 |

S. aureus accounted for 33 % of SSTIs, rare CA-MRSA |

| Mainland [87] | 2008–2010 | 8 regional pediatric hospitals | 435 | 195 | 240 (55 %) | 163 (68 %) by epidemiology | MRSA with 14 MLSTs: ST1, ST7, ST45, ST59 (50 %) ST88, ST217, ST239, ST338, ST398, ST509, ST910, ST965, ST1349, ST1409 | ~50 % MDR in CA-MRSA |

| Chengdu [150] | 2004–2006 | Pediatric infections | 51 | 41 | 10 (20 %) | 7 (70 %) 40 (78 %) CA-SA |

20 STs (eight absent from carriage): ST121 (14 %), ST88 (15 %), ST398 (12 %), ST5, ST7 Diverse CA-MRSA: STs 5, 20, 88, 121, 188, 573, 623 |

No ST59 in disease MRSA’s |

| 801 Children nasal carriage | 147 | 138 | 9 | 9 (100 %) | MSSA 26 STs: CC121 (34 %), ST50 (10 %), ST398 (8 %), ST944, ST15, ST573 MRSA: 6/9 ST59, ST398, ST30, ST942 |

No evidence for significant CA-MRSA clone | ||

| Hong Kong [151] | 2006–2007 | SSTIs at six Emergency Departments | 126 of 298 cases | 105 | 19 (15 %) | Not defined | None | CA-MRSA in all SSTIs represents rise to prior |

| Taiwan [152] | 2000–2006 | National Taiwan University Hospital | 42 | N.A. | 42 (100 %) | 25 (59 %) by epidemiology | CA-MRSA: ST59-V T- PVL+and variants (96 %), ST30 (4 %) HA-MRSA: ST239 (41 %), ST59 (24 %), ST5 |

Potential spread of clones |

| Japan [153] | 2008–2009 | National survey of 16 institutions | 857 | N.A. | 857 (100 %) | 117 (14 %) defined as outpatients | No clonal typing. SCCmec II (74 %), SCCmec IV 20 % SCCmec I (6 %) |

Increase in SCCmecIV as possible rise of CA-MRSA |

| Japan [154] | 2009 | Outpatients in Hokkaido | 1,015 | 826 | 189 (19 %) | Not defined | MRSA: ST5-II- PVL-(83 %), ST6/ST59, SCCmecIV 6.9 %, V 3.2 % | Potential emergence of CA-MRSA |

| Japan [91] | 2008 | Collection of MRSA isolates from outpatients with SSTIs at teaching hospital in Tokyo | 57 | N.A. | 57 (100 %) | 17 (30 %) defined by SCCmec IV | SCCmec IV isolates: CC8 (59 %), ST59 (12 %), ST89 (12 %), ST88 (6 %), ST93 (6 %), ST764 (6 %); 29 % PVL+ | 68 % SCCmec II 11 % PVL+ |

| India | ||||||||

| India [155] | 2011–2012 | All S. aureus infections at private district hospital | 201 | 67 | 134 (66 %) | 77 (57 %) | None | Suggests MRSA replacing MSSA in CA-SA infections |

| India [156] | 2006–2009 | Random collection of MRSA at tertiary care hospital 61 % inpatient 39 % outpatient |

412 | 17 | 395 (96 %) | 154 (39 %) by epidemiology | Of 55 MRSA isolates typed: ST22-MRSA-IV- PVL+(53 %) ST772-MRSA-V- PVL+(24 %) ST239-MRSA-III- PVL - (24 %) all HA-SA |

64 % PVL+, Increase in SCCmecIV/V and SSTIs over time |

| Mumbai [157] | 2007–2008 | Community SSTIs (n=820) | 451 | 451 | 0 (0 %) | All CA-SA by epidemiology No CA-MRSA |

None | No evidence of CA-MRSA |

| Bengaluru, Mumbai, Hyderbad, Delhi [158] | 2006–2008 | Carriers Infectious |

38 30 |

28 12 |

10 (26 %) 18 (60 %) |

Not defined Not defined |

Fifteen STs, ST22, ST772 MRSA: ST22, ST772; ST30, ST672, ST1208 |

All SCCmec IV or V |

| Karachi, Pakistan [159] | 1997 2006–2007 |

Patients with MRSA infection | 37 126 |

N.A. | 37 (100 %) 126 (100 %) |

Unknown 19 (15 %) by epidemiology |

HA-MRSA: ST239-III (56 %), ST8-IV (44 %) CA-MRSA: five PFGE types, ST8-IV (67 %), ST239 (16.7 %) |

Overlap of CA- and HA-MRSA clones |

| Pakistan [160] | Before 2010 | Four tertiary hospitals (three in Pakistan, one in India) | 60 | N.A. | 60 (100 %) | Unknown | PFGE/SIRU: CC8 (95 %), CC30-IV=PVL (3 %) MLST of CC8s (n=14): ST239-II/III (64 %), ST8-IV (21 %), and ST113-IV (14 %) |

SIRU=staphylococcal interspersed repeat units |

| Siem Reap, Cambodia [161] | 2006–2007 | Pediatric inpatients and outpatients with MRSA | 17 | N.A. | 17 (100 %) | 16 (94 %) by epidemiology | ST834-IV-PVL-(88 %), ST121-IV-PVL+ | First report of (CA)-MRSA in Cambodia |

| South Korea [89] | 1996–202005 | Random selection of infection and colonization S. aureus isolates | 335 | 139 | 196 | Not defined | MRSA: ST5 (48 %), ST239 (23 %), ST72 (7 %), ST1 (5 %), ST254 (3 %), ST30 (3 %) MSSA: ST1 (22 %), ST6 (12 %), ST30 (9 %), ST59 (7 %); less than 5 %: ST5, ST580, ST15, ST72 |

Emergence of ST72 over period of study |

| South Korea [90] | 2004–2007 | MRSA BSI at five hospitals | 76 | N.A. | 76 (100 %) | 4 (5.3 %) by epidemiology | HA-MRSA: ST5 (61 %), ST239 (13 %), ST72-IV (25 %), ST1 CA-MRSA (n=4): ST72-IV (50 %), ST5-II (50 %) |

CA-MRSA ST72 invading the hospital |

STs in bold represent most frequent clone, BSI = blood stream infections, MDR = multidrug resistance, >3 classes of antibiotics

Table 2.

Molecular epidemiology of S. aureus carriage in diverse geographic regions

| Region | Year | Population | N | S. aureus carriage | MRSA carriagea | Molecular Typing | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||||

| Mali [102] | 2005 | Patients for emergency surgery at tertiary care hospital | 448 | 88 (20 %) | 1 (0.22 %) | MSSA: 20 STs, ST15 (27 %), ST152-PVL + (24 %), also ST5, ST8, ST291, ST88, ST30, ST1 MRSA isolate: ST88 |

Low resistance, except to penicillin and tetracycline Presence of pandemic clones |

| Nigeria [162] | Before 2007 | Medical students | 182 | 26 (14 %) | 0 (0 %) | None | No MRSA carriage |

| Nigeria [163] | 2009 | Healthy villagers University students |

60 60 |

17 (43 %) 23 (58 %) |

10 (8.3 %) | None | 21 (53 %) MDR 10 (91 %) of MRSA isolates MDR 3 (7.5 %) pan-sensitive |

| Gabon [105] | 2008–2010 | Healthy carriers from community, healthcare | 552 | 163 (30 %) | 6 (1.1 %) | MSSA: ST15 (46 %), ST508 (8.5 %), ST152 (6 %), ST1 (5 %), <5 %: ST5, ST6, ST88, ST7, ST72, ST9 MRSA: ST88 (67 %); ST 8, ST5 |

41 % PVL+ |

| Gabon [81] | 2009 | Babongo Pygmies | 100 | 33 (33 %) | None | 34 isolates: ST30 (24 %), ST15, ST72, ST80, ST88 (each 12 %) | Remote indigenous population 56 % PVL+, Low resistance |

| Middle East | |||||||

| Israel [164] | 2002 | Children at clinic Parents |

1,768 1,605 |

580 (17 %) | 5 (0.15 %) | MSSA: ST45 (25 %) MRSA (n = 5): ST247, ST5, ST45 |

Two CA-MRSA by epidemiology |

| West Bank [165] | 2003 | Inpatients | 843 | 218 (26 %) | 17 (2.0 %) | None | No prior healthcare exposure, low resistance to non-β-lactams |

| Palestine [166] | 2011 | Students | 360 | 86 (24 %) | 8 (2.2 %) | No clonal typing All MRSA SCCmec IVa |

Nearly 35 % of isolates resistant to two or more non-β-lactam antibiotics |

| Gaza-Strip [116] | 2009 | Children (<5.5 years) Parents |

379 379 |

107 (28 %) 108 (28 %) |

50 (13 %) 44 (12 %) |

MSSA (40 isolates analyzed): ST291 (21 %), ST1278 (18 %), ST15 (18 %), ST22 (13 %) MRSA: ST22 (73 %), ST78 (7 %), ST80 (5 %); 8.5 % PVL+ |

64 % of MRSA isolates were ST22-MRSA-IVa- PVL-(susceptible to all non-B-lactam antibiotics) |

| Hamadan Iran, [167] | Before 2011 | Daycare children | 500 | 148 (30 %) | 6 (1.2 %) | None | Age range 1–6 years, no MRSA no risk factors |

| Lebanon [168] | 2006–2007 | Students and employees | 500 | 193 (38 %) | 8 (1.6 %) | None | Age 6–65 years Highest carriage rate in children |

| Latin America | |||||||

| Gioania Central Brazil [169] | 2005 | Daycare children aged 0.2–5 years | 1,192 | 371 (31 %) | 14 (1.2 %) | MRSA: ST239 (57 %), ST121 (21 %), ST30 (7 %), ST12 (7 %), ST1120 (7 %) SCCmec IIIA, IV, and V detected All PVL negative |

7 (50 %) of MRSA were MDR MRSA carriers with prior hospitalization or antibiotics |

| Amazonian rainforest [118] | 2006 2008 |

Adult Wayampi Amerindians | 154 | 65 (42 %) 89 (58 %) |

None |

ST1 (25 %), ST188 (20 %), ST1223 (19 %), ST15 (15 %), ST5 (14 %), <5 %: ST97, ST30, ST398, ST1292, ST1293 ST1223 (35 %), ST5 (17 %), ST1 (15 %), ST188 (13 %), ST97 (6 %), <5 %: ST72, ST30, ST718, ST432, ST14, ST15, ST398 |

Isolated population in French Guiana, increased in S. aureus incidence in 2008 |

| Bolivia, Peru [170] | 2008–2009 | Healthy volunteers | 585 | N.R. | 3 (0.5 %) | All MRSA ST1649-IV (CC6) | One urban area, one small village, two native communities, one person recently hospitalized |

| Asia | |||||||

| Japan | |||||||

| South [171] | 1999 | Daycare children | 156 | 28 (18 %) | 12 (7.7 %) | None | Age range 0.1–5 years |

| Tokyo [172] | 2007 | Tertiary hospital admissions | 267 | N.R. | 30 (11 %) | None | Used PCR and culture |

| Japan [173] | 2006–2008 | Pediatric outpatients Healthy children |

426 136 |

125 (29 %) 55 (40 %) |

3 (0.7 %) 5 (3.7 %) |

ST88-IV, ST5-II, ST857-II ST8-IV (n=2), ST764-II, ST22-I, ST380-IV |

All MRSA considered CA by epidemiology All PVL- |

| Sado Island [174] | 2008–2012 | Pediatric outpatients Healthy children, <15 Healthy children |

3,939 1,333 136 |

N.R. 55 (40 %) |

15 (0.4 %) 26 (2.0 %) 5 (3.7 %) |

MRSA: ST8-IV/I (20 %), ST5-II/IV (17 %), ST764-II (15 %), ST92-IV (12 %), ST59-IV (10 %), ST121-V (10 %), ST509, ST81-IV, ST2180-IV | All MRSA classified as community-onset (CO) MRSA, genetically diverse All PVL-negative |

|

| |||||||

| China | |||||||

| Hong Kong [175] | Before 2004 | Students and their families | 653 | 186 (29 %) | 9 (1.4 %) | None | |

| Shenyang [176] | 2008–2009 | Medical students | 2,103 | 234 (11 %) | 22 (1.0 %) | MRSA: ST88 (45 %), ST59 (18 %), ST30 (14 %), ST5 (9 %); ST90, ST239 and ST1 (one each) | Ten MRSA PVL+ |

| Wenzhou (Southeast) [177] | Before 2011 | Volunteers on medical campus | 935 | 144 (15 %) | 28 (3.0 %) | MRSA: Diverse with 16 ST’s for 28 isolates, ST59 (14 %), ST25 (11 %), also ST188, ST438 | 82 % of MRSA and 66 % of MSSA isolates were resistant to multiple antibiotics, one MDR ST398-MRSA-V |

| Hong Kong [178] | 2009–2010 | Kindergarten and daycare children (2–5 years) | 2,211 | 610 (28 %) | 28 (1.3 %) | MRSA: ST59-IV/V (32 %), ST45-IV/V (25 %), ST10-V (14 %); also CC1-IV, ST30-IV, CC5-IV, ST630-V, ST88-V MSSA highly diverse (51 spa types in 101 isolates) |

All 18 geographical districts sampled Seven children had both MSSA and MRSA |

|

| |||||||

| Taiwan | |||||||

| North [179] | 2004–2009 | Healthy children (≤14 years) | 3,200 | 824 (26 %) | 371 (12 %) | MRSA: ST59 (86 %); 4.3 % of MRSA MDR ST338 (ST59 variant) | Decrease in MSSA (22– 4.4 %) paralleled by increase in MRSA (11.6–17.6 %) from 2004 to 2009. High ery/clinda resistance |

| North [180] | Before 2007 | Day care children (<7 years) | 68 | 17 (25 %) | 9 (13 %) | All MRSA ST59-IV-PVL- | No healthcare exposures High ery/clinda resistance |

| North [181] | 2008 | Medical and surgical ICU patients | 177 | 74 (42 %) | 57 (32 %) | MRSA: ST5-II-PVL-(34 %), ST239-III-PVL-(26 %), ST59-SCCmec IV or V T (16 %) | Tertiary hospital population |

| North, South and Central [182] | 2005–2008 | Healthy children at outpatient check-up | 6,057 | 1,404 (23 %) | 473 (7.8 %) | MRSA (279 typed): ST59/ST338-IV/PVL-(59 %), ST59/ST338-VT/PVL+(23 %) Other: ST5, ST239, ST89 | Highest MRSA incidence in North (27.4 %), lowest in central Taiwan (20.3 %); High incidence of MDR (88 % of ST59) |

| Rural North [183] | Before 2012 | Medical students | 322 | 62 (19 %) | 7 (2.2 %) | All MRSA: ST59 (6/7) SCCmec IV/PVL-, 1 of 7 SCCmev V T/PVL+ | No difference between preclinical and clinical students High ery/clinda resistance |

| Taiwan [184] | 2003–2008 | Healthy children | 3,305 | 495 (15 %) | 0 (0 %) | Only PVL + MSSA typed (5/495) All ST59 PVL+SCCmec VT |

Age group <18 years. |

| North [185] | 2009 | Adults emergency department | 502 | 87 (17 %) | 19 (3.8 %) | MRSA: ST59 (58 %), ST239 (32 %); majority of ST59 CA-MRSA | MRSA carriage 5.9 % in patients with HA risk factors, 2.1 % in patients without CA-MRSA |

| South Korea [186] | Before 2008 | Pediatric outpatients | 296 | 95 (32 %) | 18 (6.1 %) |

ST30 and variants (36 %) ST72 among MRSA |

Age range 1–11 years |

| Seoul South Korea[187] | 2008 | Daycare children | 428 | 164 (38 %) | 40 (9.3 %) | ST72 (73 %), ST1765 (15 %), ≤5 %: ST1, ST1735, ST1736, ST1737; All PVL- | Age range 1–6.8 years |

|

| |||||||

| India | |||||||

| Mangalore, [92] | Before 2007 | Medical students | 50 | 44 (88 %) | 12 (24 %) | None | High MRSA carriage |

| Ujjain [188] | 2007 | Pediatric outpatients | 1,562 | 98 (6.3 %) | 16 (1 %) | None | Children 0.1–5 years Four MSSA and three MRSA isolates MDR |

| Andhra Pradesh [189] | Before 2009 | School children | 392 | 63 (16 %) | 12 (3.1 %) | None | Age group 5–1 (age 5–15) years |

| India [190] | Before 2009 | School children | 489 | 256 (52 %) | 19 (3.9 %) | None | Rural, urban, and semi-urban slums, 5–15 years |

| Nagpur, [191] | Before 2009 | School children | 1,300 | 96 (7.4 %) | 4 (0.3 %) | None | Urban children (6–10 years) |

| Lahore, Pakistan [192] | 2002–2003 | General population | 1,660 | 246 (15 %) | 48 (2.9 %) | None | Rural and urban community population |

| Pokhara, Nepal [193] | Before 2008 | School children | 184 | 57 (31 %) | 32 (17 %) | None | Age group <15 years |

| Thailand [194] | Before 2011 | Healthy young adults | 200 | 30 (15 %) | 2 (1 %) | Both MRSA isolates were SCCmec type II | Carriage associated with healthcare risk factors |

| Siem Reap, Cambodia [195] | 2008 | Outpatient Inpatients |

2,485 145 |

Not reported | 87 (3.5 %) 6 (4.1 %) |

MRSA: ST834 (91 %), also ST121, ST188, ST45, ST9 | 28 (32 %) of 87 outpatient carriers were considered CA-MRSA |

| Java, Indonesia [196, 197] | 2001–2002 | Healthy individuals and patients | 3,995 | 329 (8.2 %) | 1 (0.03 %) | Genetically diverse MSSA: ST45, ST188, ST121 10.6 % PVL + (ST188 and ST121) |

Only MRSA case was isolated from patient after 45 days of hospitalization |

| Java, Indonesia [198] | 2006 | Outpatients and adult companions | 440 | 62 (14 %) | 0 (0 %) | CC1 (21 %), CC45 (18 %), CC8 (8 %), CC15 (6 %); less | Low antibiotic resistance 10 MSSA (16 %) PVL+ |

| Malaysia [199] | Before 2008 | University students | 100 | 26 (26 %) | 8 (8 %) | CA-MRSA (n=3): ST1004-V PVL-, ST80-IVa PVL+ | No MDR |

N.R.=not reported

MRSA carriage of individuals (number MRSA ± number swabbed)

Asia: Information on S. aureus infections are lacking from many parts of the Asian continent. Overall, there appears to be a relatively low burden of MRSA in general and CA-MRSA in particular (Table 1). However, ST59 (Taiwan clone) is the most frequent strain encountered in Taiwan, China and across other parts of the Asia (Tables 1 and 2) [85]. In parallel, ST239 is widespread as a cause of nosocomial MRSA infections in South Korea, Malaysia, China, Taiwan, India, and Pakistan (Table 1).

In Taiwan, the high frequency of MRSA infections with ST59 is also paralleled by a remarkably high nasal carriage rate of MRSA and ST59 in some but not all studies of daycare or school-aged children (~8–13 %), (Table 2). ST59 also contributes to MRSA infections and in particular MRSA carriage in China. There are greatly varying reports on the prevalence of CA-MRSA in China, ranging from only ~1 % in several studies to up to 68 %. The two studies reporting a high burden of CA-MRSA infections, which were defined by epidemiology, were also remarkable in that they suggested circulation of HA-MRSA clones in the community and a relatively high proportion of multidrug resistance in CA-MRSA isolates [86, 87]. However, there appears to be very infrequent nasal colonization with MRSA (1–3 %) across different Chinese populations (Tables 1 and 2). Of note, genotyping of MSSA isolates, the major contributor to community-associated S. aureus infections in China, revealed a number of pandemic clones such as ST121, ST88, and ST188 as well as a consistent prevalence of PVL positive ST398 (Table 1). This strain was first mainly recognized in Europe as livestock associated PVL-negative MRSA [88]. The relationship of the frequent occurrence of ST398 colonization and infection with ST398 MSSA in China and ST398 infections in Europe remains unclear.

Colonization studies from children in South Korea showed a relatively high MRSA prevalence (6.1–9.3 %) and were mainly accounted for by ST30 and ST72 (Table 2). ST72 in particular contributes to MRSA infections [89], and these strains have also become established in the hospital environment [90].

Several reports of small outbreaks have described CA-MRSA in Japan but only relatively recently an increase in SCCmec-IV isolates, interpreted as an increase in CA-MRSA genotypes, was noted (Table 1). Further genotyping indicated that these CA-MRSA are notably polyclonal [91] and include to varying degrees ST59, a diversity of CC8 strains (including USA300) as well as small numbers of ST89, ST88, and ST93 (Table 1). MRSA carriage in non-hospitalized Japanese patients was also generally low and has been attributed to a high diversity of strains, including ST5, ST8, ST59, and ST88 (Table 2).

Little evidence for CA-MRSA has been published from Malaysia, Indonesia and Cambodia. Among the few cases of CA-MRSA in Malaysia, ST188, ST1, ST30, and ST80 predominated (Table 1), whereas in Cambodia the first report of CA-MRSA was due to a ST834 strain. In Indonesia, MRSA carriage was negligible and published data on infections are lacking. A number of studies from India, mainly conducted at hospital centers, suggest a relatively high prevalence of MRSA, but the contribution of CA-MRSA to S. aureus infections is less clear. To date, strains ST22 and ST772 have been identified as major CA-MRSA clones among infectious isolates (Table 1). The MRSA colonization prevalence also appears to be low with the exception of one investigation of medical students of whom 24 % were colonized [92]. In Pakistan, both, CA- and HA-MRSA strains were found to overlap with ST239-II/III and ST8-IV predominating (Table 1).

Africa: MRSA was only first described in Africa in 1988 [93] and to date only limited information on the epidemiology of S. aureus infections is available from most of the continent. Studies on the prevalence of MRSA in Africa span from less than 10 % to up to nearly 50 % (Table 1). In a large survey of 1440 S. aureus isolates collected across Nigeria, Kenya, Morocco, Cameroon, Tunisia, Algeria, Senegal, Cote D’Ivoire, and Malta from the late 1990s, ~15 % were MRSA [94]. The highest frequency was noted in Nigeria, Kenya, and Cameroon (at 21–30 %) and lowest in the North African countries Malta, Tunisia, and Algeria (below 10 %). However, there were no data available regarding the epidemiological profile of these isolates and in light of their reported high frequency of multidrug resistance these infections may have been most consistent with HA-MRSA.

Overall, there is relatively little published evidence for a substantial CA-MRSA epidemic in North Africa. Despite the relatively low overall MRSA frequency, severe cases of invasive CA-MRSA requiring admission to the pediatric ICU have been documented over a 10 year period in Tunisia with an increase in incidence over the last year of the study [95]. Despite these relatively low numbers, major international lineages have been reported from the region, such as the predominant European CA-MRSA lineage ST80 in Algeria, Egypt, and Tunisia [96, 97] (Table 1). In Algeria, this relatively high prevalence of ST80-MRSA was already prevalent about a decade ago. While 86 % of CA-MRSA isolates were PVL+, an unusually high percentage of HA isolates also harbored PVL (68 %). Several of these isolates were multidrug resistant, consistent with HA-MRSA. The authors suggested that poor hygiene might have contributed to the spread of PVL positive strains into the hospital setting.

In a large study from five African towns in Cameroon, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, and Madagascar, ST239/241 (Morocco and Niger), ST88 (Cameroon and Madagascar), and ST5 (Senegal) accounted for the majority of MRSA infections [98]. ST88 had been sporadically encountered in Belgium [99], Portugal [100], and Sweden [101].

The pandemic spread of many of the common S. aureus clones and the evolution of a divergent PVL + ST152 clone was also documented in a nasal carriage population of 448 patients in Mali [102]. Overall, ~20 % of individuals were S. aureus carriers and only one patient harbored MRSA. The most common MSSA sequence types were ST15 and ST152 accounting for about half of the isolates. Additional ST include ST5, ST8, ST291, ST30, ST88, and ST1. All of the ST152 isolates carried PVL. This clone has been associated with sporadic disease in Central Europe [84].

In Eastern Nigeria, one of the most populated African countries, the reported MRSA prevalence ranges from 1 to 41 % of S. aureus infections (Table 1) with a low or undefined burden of CA-MRSA infections [103, 104]. In a study from the South Western part of the country in 2007, a sizable number of ophthalmological and auricular CA-MRSA infections were reported, mainly caused by ST88-IV-PVL+. All of these isolates were also resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In addition, cases of ST8 infections, including ST8-t064/t451 suggestive of USA500 have been sporadically described. The bulk of HA-MRSA is mainly attributable to ST241 and ST250. MSSA infections in Nigeria have been due to a diversity of clones, with a substantial representation of ST15, ST5, ST88, and PVL-positive ST152 [84] (for additional STs see Table 1).

ST15 (t084) also predominated amongst carriage and infectious isolates from Gabon and a variety of ST15 associated spa-types accounted for almost half of all carriage isolates [105]. Carriage was relatively low at ~29 % using three body sites (nares, axilla, and groin), and the carriage MRSA prevalence was 3.6 %. The contribution of MRSA to the infection isolates was low at 11 % and was mainly due to ST88 (67 %). ST1 (all MSSA) and ST88 (all MRSA isolates) were more frequently present among infectious isolates, whereas ST508 was associated with carriage. Only one of the 12 MRSA isolates was PVL positive, arguing against a direct linkage of PVL + MSSA as the precursor for MRSA.

The nasal S. aureus carriage in the remote indigenous Gabonese Babongo Pygmies was about 30 % and no MRSA was detected [81]. ST30 was most common (24 %) among the ten diverse sequence types, which also included ST15, ST72, ST80, and ST88 (Table 2) and more than half of all isolates carried PVL. The genetic background of these isolates matches pandemic CA-MRSA strains. This observation again raises the possibility that African PVL + MSSA served as a reservoir for pandemic MRSA clones. Alternatively, PVL + MSSA isolates, such as ST30, could have been introduced to Africa by European travelers or rather represent archaic S. aureus clones that globally predominated before the emergence of MRSA.

In South Africa, several studies have also identified the presence of pandemic clones as a cause of the vast majority of MRSA infections, whereas the burden of CA-MRSA infections is less clearly defined (Table 1). However, in a study of 161 patients with community-onset bacteremias (incidence of 26/100,000), 39 % were due to MRSA [106]. The MRSA incidence was increased in HIV infected patients and children. Multidrug-resistance was generally high among MRSA isolates and in particular among HIV-infected children. A greater prevalence of community-acquired S. aureus pneumonia was also noted in HIV-positive children compared to their HIV-negative peers [107]. While no clonal typing was reported in these two studies it is notable that ST612-IV (also genotyped as spaCC64 and USA500 by PFGE) was noted as one of the most predominant strains [108, 109]. ST612-IV accounted for the majority of, albeit infrequent, CA-MRSA from hospitals in Cape Town [108]. ST612 itself was previously only sporadically described in Germany as well as in Australian horses [110, 111]. Notably, these ST612 isolates contain spa t064 and have a PFGE pattern consistent with USA500. Interestingly, USA500 the presumed precursor of USA300, has been closely associated with infections and colonization of HIV/AIDS patients in the USA, although USA300 still accounts for the majority of cases of S. aureus in HIV [112]. It has been estimated that the HIV prevalence is ~17.3 % in the general population in South Africa. The South African molecular studies on S. aureus have not commented on the HIV prevalence in their study populations, but based on these data it is intriguing to speculate that the relatively high HIV prevalence contributes significantly to the clonal type of MRSA infections in this country. Furthermore, this association points to an important interaction between the immune status of the host and the clonal background of the infecting S. aureus strain.

Middle East: The reported MRSA prevalence in Middle Eastern countries ranges from less than 5 % in the United Arab Emirates [113] to up to 75 % in a random collection of S. aureus isolates from Lebanon (Table 1). These numbers are likely skewed by the proportion of inpatient and outpatient surveyed in these studies. However, across the region, the international HA-MRSA clone ST239, mainly associated with SCCmecIII, has been reported from many different countries, including Lebanon, Kuwait, Iran, and Saudi Arabia (Table 1). Although CA-MRSA isolates were only represented at a relatively low frequency among MRSA infections, in particular in Iran and Bahrain (2–13 %), pandemic ST80-IVc and ST30-IV are widespread and causing infections in Lebanon, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia (Table 1). In Kuwait, CA-MRSA ST30-IV, ST80-IV and isolated cases of ST8-IV, ST5-IV, and ST728-IV were detected as early as 2001 during a national survey of S. aureus isolates, although MRSA only accounted for ~5 % of all S. aureus infections [114]. Most other major clonal complexes such as ST5-IV, ST6-IV, ST8-IV, ST22-IV, and ST97 have been reported at lower frequencies. These clonal complexes are also well represented among MSSA isolates and are a significant cause of S. aureus infections, including in the nosocomial setting such as ST8-MSSA in an Iranian hospital [115].

Colonization with MRSA was also generally low in community studies from Lebanon, Iran, Israel, the West Bank, and Palestine (0.9–2.2 % of individuals) with the exception of a child–parent cohort study that reported MRSA colonization in ~12 % of participants (Table 2). In this Palestinian-Israeli collaboration, children younger than 5.5 years and one of their parents in 12 Gaza neighborhoods and villages were surveyed [116]. The overall prevalence of S. aureus carriage was ~30 %. The only predictor for MRSA carriage in children was having a MRSA positive parent. Molecular analysis of the MRSA isolates revealed a low genetic diversity as 64 % were accounted for by the ST22-IVa-t223-PVL - “Gaza strain” (CC22 in 75 % of MRSA), which had low non-β-lactam resistance. This strain was found to be closely related to local MSSA spa t223 strain and less related to EMRSA-15. In addition, MRSA isolates belonging to CC88 (7.4 %) and CC80 (5.3 %) were also identified. PVL was only infrequently present among MRSA isolates (9 %) and MSSA isolates.

Latin America: Relatively little is known about the possible burden of CA-MRSA in Latin America. However, the presence of the three pandemic clones ST5, ST8, and ST30 has been described from multiple regions and which appear to account for the majority of CA-MRSA infections. The spread of a USA300-like clone into Latin America has been documented in Cuba and further south in the neighboring countries of Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela (Table 1). In contrast to the majority of North-American USA300, these ST8 isolates harbor the SCCmec-IVc and are usually ACME negative. Some of these ST8 infections have also occurred in the hospital setting.

In Argentina, ST5 accounted for the vast majority of CA-MRSA infections [117]. In contrast to the hospital-associated MRSA infections from elsewhere, these isolates mainly harbored SCCmec-IVa and were also PVL positive. Previously, ST5 PVL + MSSA had circulated in the area as the possible precursor of this MRSA. Most of the reported CA-MRSA in the neighboring country of Uruguay has been attributed to ST30-IVc-PVL isolates (Table 1).

Only a limited number of S. aureus colonization studies have been reported from these Latin American countries and have generally reported a low MRSA prevalence (0.5–1 %) in diverse populations in Bolivia, Peru and Brazil (Table 2). Although only 1 % of daycare children were colonized with MRSA in a Brazilian study, the pandemic MRSA ST239 accounted for 57 %. None of these children previously had been hospitalized or received antibiotic treatment. No MRSA was detected among the Wayampi Amerindians in the Amazonian rainforest [118]. In this study, the 2006 to 58 % in 2008. Of these, 26 % of individuals were considered persistent carriers. Penicillin resistance was at 99 % in a community with high antibiotic usage. There was an overall low diversity index of the strains, which in part likely reflects the close family ties and living conditions. Two phylogenetic groups were observed with phylogenetic group 2 (ST1, ST5, ST14, ST15, ST72, ST97, ST188, ST432, ST1292, and ST1293) accounting for 79 % in 2006 and 58 % in 2008. Rare isolates belonging to ST30, ST398, and ST718 were also observed. A rare and phylogenetically distant ST1223 accounted for 19 % of colonization isolates in 2006 and 35 % in 2008. The predominant prevalence of a single clone suggests a preferential adaptation to a given population. This clone had only previously been described in Cambodia [119]. Interestingly, a closely related sequence type is ST75, the original CA-SA clone from indigenous populations in Australia. The authors suggested that an association between populations living under isolated conditions might reflect ancient human migration and coevolution of bacteria and their hosts [118]. A study from the Caribbean islands of Martinique and the Dominican Republic also documented the presence of rare international clones such as ST72 (seen in South Korea) and ST152 (present in parts of Europe and Africa). The study speculated that tourists might have imported these strains, as both countries are frequent traveler’s destinations. Alternatively, these clones may be more prevalent in populations that previously were less frequently sampled.

4 Conclusions

The past 20 years have seen a dramatic change in the epidemiology of S. aureus infections with the emergence of CA-MRSA clones manifesting as an epidemic of SSTIs infections in many parts of the world. However, MSSA infections continue to contribute to the burden of S. aureus disease. In a reversal of epidemiology, there is mounting evidence that CA-MRSA continuing to replace HA-MRSA in clinical setting.

The evolution of drug resistance, in particular VISA and VRSA, poses a clinical dilemma, as few viable treatments are available. In addition, information on S. aureus strains is still lacking from many parts of the world, while it appears that novel S. aureus strains are continuously evolving—or only now being detected. This evolution also spans an exchange of S. aureus clones with zoonotic reservoirs, such as ST398 from pigs, other livestock, and humans. Animals have also been identified as a reservoir and source for the emergence of novel resistance elements such as the novel bovine mecA gene homologue, mecA (LGA251), now designated mecC [120, 121].

While it appears that the distribution of S. aureus remains geo-USA300 but also ST30, ST80, ST1, ST59, and ST93, between countries and across continents is increasingly observed. Although traditional molecular typing methods have provided important clues as to how pandemic clones are spreading, they have provided limited information on the directionality of transmission and evolution of particular S. aureus lineages. However, the advent of novel technologies such as whole-genome sequencing allows for more sensitive ways to understand how particular S. aureus strains have evolved independently or rather migrated around the world [42, 122, 123].

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grant K08 AI090013 from the National Institute of Health and the Paul A. Marks scholarship.

References

- 1.Noble WC, Valkenburg HA, Wolters CH. Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in random samples of a normal population. J Hyg (Lond) 1967;65:567–573. doi: 10.1017/s002217240004609x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jevons MP, Parker MT. The evolution of new hospital strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Pathol. 1964;17:243–250. doi: 10.1136/jcp.17.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saravolatz LD, Markowitz N, Arking L, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Epidemiologic observations during a community-acquired outbreak. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:11–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine DP, Crane LR, Zervos MJ. Bacteremia in narcotic addicts at the Detroit Medical Center. II. Infectious endocarditis: a prospective comparative study. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:374–396. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Udo EE, Pearman JW, Grubb WB. Genetic analysis of community isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Australia. J Hosp Infect. 1993;25:97–108. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90100-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardam MA. Is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus an emerging community pathogen? A review of the literature. Can J Infect Dis. 2000;11:202–211. doi: 10.1155/2000/424359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tenover FC, Tickler IA, Goering RV, et al. Characterization of nasal and blood culture isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in United States Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1324–1330. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05804-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seybold U, Kourbatova EV, Johnson JG, et al. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:647–656. doi: 10.1086/499815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefani S, Chung DR, Lindsay JA, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): global epidemiology and harmonisation of typing methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome E. Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malachowa N, Kobayashi SD, Deleo FR. Community-associated methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus and athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40:13–21. doi: 10.3810/psm.2012.05.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Begier EM, Frenette K, Barrett NL, et al. A high-morbidity outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among players on a college football team, facilitated by cosmetic body shaving and turf burns. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1446–1453. doi: 10.1086/425313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkland EB, Adams BB. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and athletes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen DM, Mascola L, Brancoft E. Recurring methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a football team. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:526–532. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.041094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aiello AE, Lowy FD, Wright LN, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among US prisoners and military personnel: review and recommendations for future studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:335–341. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adcock PM, Pastor P, Medley F, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two child care centers. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:577–580. doi: 10.1086/517478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]