Abstract

A series of novel, potent orthopoxvirus egress inhibitors was identified during high-throughput screening of the ViroPharma small molecule collection. Using SAR information inferred from early hits, several compounds were synthesized, and compound 14 was identified as a potent, orally bioavailable first-in-class inhibitor of orthopoxvirus egress from infected cells. Compound 14 has shown comparable efficaciousness in three murine orthopoxvirus models and has entered Phase I clinical trials.

Once considered a scourge of mankind, the smallpox (variola) virus has gained notoriety as a potential biological threat. Although mass vaccination remains the primary response by national public health agencies to a terrorist attack using variola virus, concerns over vaccine-related adverse events have prevented institution of a general immunization program.1 Additionally, the induction period required for a vaccine-induced immune response will necessitate a period of risk before establishment of protective immunity (the “immunity gap”). While several small molecule inhibitors of orthopoxvirus replication have been identified, non-specific mechanism of virus inhibition has resulted in narrow therapeutic windows.2 The nucleotide analogue Cidofovir (CDV; 1-[(S)-3-hydroxy-2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]cytosine dihydrate) is the best studied of these.3 Approved for treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in AIDS patients, this broad spectrum viral DNA polymerase inhibitor4 is administered intravenously, and dose-limiting nephrotoxicity requires additional management.3b While work continues to address the shortcomings of CDV,5 there is a recommendation from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies to identify additional inhibitors with alternate mechanisms of action.3b, 6 Here, we report on the identification, synthesis, and structure-activity relationships (SAR) of a series of novel, orally bioavailable, orthopoxvirus egress inhibitors.

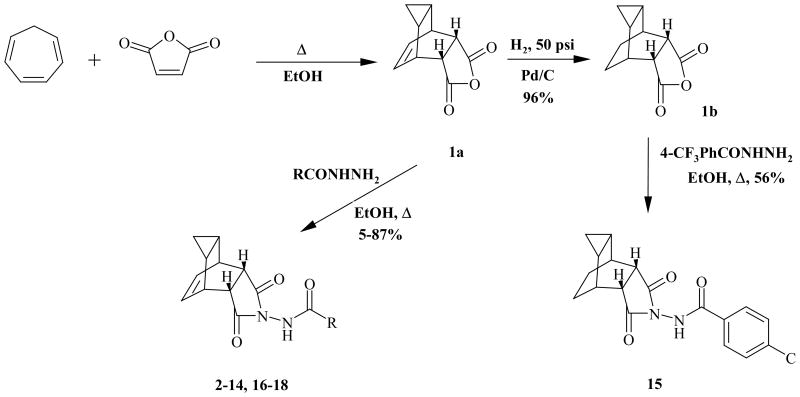

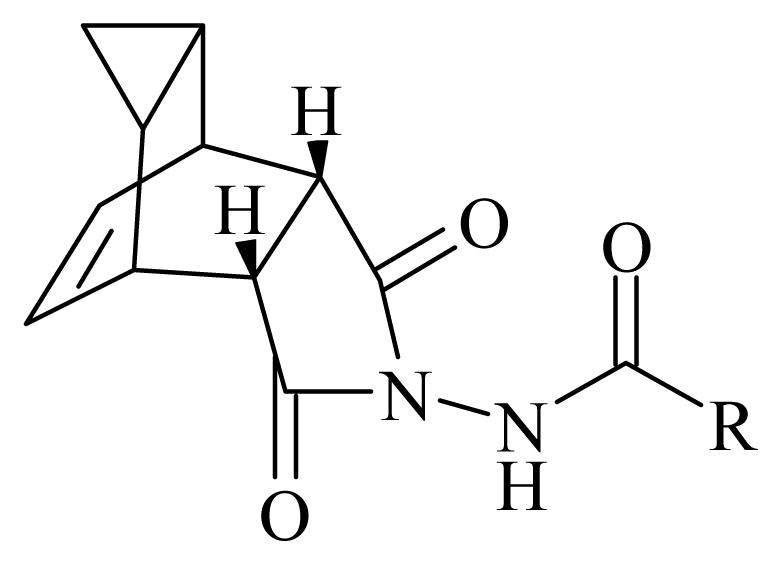

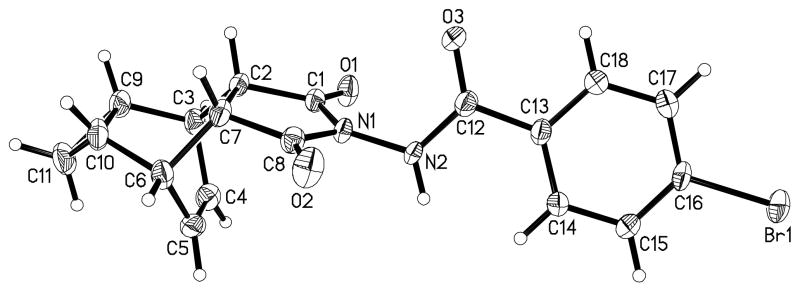

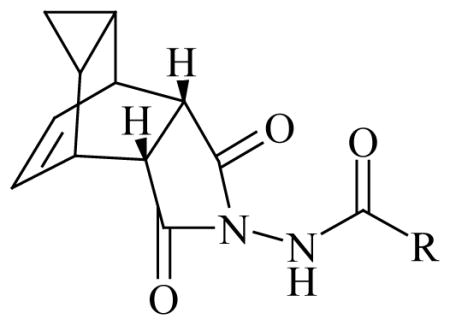

Using vaccinia and cowpox viruses, high throughput assays were used to measure virus-induced cytopathic effects (CPE) and screen approximately 356,000 commercial, low molecular weight compounds. Examination of hits from the screening revealed a series of tricyclononene carboxamides (Figure 1) with effective concentrations that inhibited 50% of the virus-induced CPE (EC50) ranging from 13 nM to the limit of testing (> 5 μM). These novel structures are unique as antiviral agents. Nascent SAR from the screening hits indicated that electron withdrawing substitution on the carboxamide aryl or heteroaryl enhanced potency of the molecules in the CPE assay. To validate this nascent SAR, a series of analogues was prepared (Scheme 1), and tested against both vaccinia and cowpox viruses in CPE assays. Synthesis of compounds 2-14 and 16-18 was accomplished in a single step via condensation of an acyl hydrazide with known tricyclononane anhydride, 1a, or its reduced form 1b.. The structure of example 13 was confirmed by x-ray crystallography (Figure 2). The synthesis of compound 15 was performed in a similar fashion from the fully saturated anhydride via catalytic hydrogenation of 1.

Figure 1.

General structure of orthopoxvirus egress inhibitors.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Compounds 2-18.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of compound 13.

In particular, electron withdrawing substitution on the carboxamide carbonyl R-group provided the most potent inhibitors of orthopoxvirus cytopathic effect (CPE) (Table 1). The 4-nitrophenyl substituted carboxamide, 2, was 100-fold more potent than the electron-donating 4-dimethylaminophenyl analogue, 3, against both vaccinia and cowpox viruses. While the aza-π-deficient 3- and 4-pyridyl examples 6 and 7 displayed potency against vaccinia, the 2-pyridyl analogue, 5, displayed a dramatic loss of potency. In all cases, heterocyclic substitution provided modest to weak potency against vaccinia virus, and exhibited no EC50 up to the highest concentrations tested against cowpox virus. For the chloro- and bromo-substituted phenyls (compounds 8-13), a similar pattern was observed for both viruses, where 3- and 4-substitution were more potent than 2-substitution. Reduction of the olefin had little effect on potency (14 and 15). Additionally, these compounds displayed excellent activity against a cidofovir-resistant strain of cowpox virus (Table 1). Examination of selected pairs (5 and 7; 11 and 13; 14 and 15) in CPE assays against vaccinia, cowpox, monkeypox, and camelpox viruses, and two strains of variola virus, established this broad-spectrum trend (where 4-substitution • 3-substitution≫>2-substitution) for the Orthopoxviridae family, and most importantly, confirmed activity against the target threat, smallpox virus (Table 2).

Table 1.

CPE Assay Screening Results.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Vaccinia EC50(μM) | Cowpox EC50(μM) | CDVr Cowpox EC50(μM) | CC50 (μM) | |

| 2 | 4-nitrophenyl | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.10 | >86 ± 20 |

| 3 | 4-Me2N-phenyl | 2.0 | 15.5 | 3.5 | >100 ± 0 |

| 4 | 4-aminophenyl | 7.7 | >20 | >50 | >92 ± 11 |

| 5 | 2-pyridyl | >20 | >20 | >20 | >100 ± 0 |

| 6 | 3-pyridyl | 0.74 | >20 | >5 | >100 ± 0 |

| 7 | 4-pyridyl | 0.5 | 17.2 | 1.8 | >100 ± 0 |

| 8 | 2-chlorophenyl | 3.0 | >20 | ND | >100 ± 0 |

| 9 | 3-chlorophenyl | 0.04 | 0.6 | ND | >100 ± 0 |

| 10 | 4-chlorophenyl | 0.02 | 0.77 | ND | >100 ± 0 |

| 11 | 2-bromophenyl | 2.3 | >20 | 4.0 | >100 ± 0 |

| 12 | 3-bromophenyl | 0.05 | 0.6 | 0.03 | >100 ± 0 |

| 13 | 4-bromophenyl | 0.02 | 1.6 | 0.1 | >100 ± 0 |

| 14 | 4-CF3phenyl | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.07 | >100 ± 0 |

| 15 | sat. 4-CF3phenyl | 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.02 | >100 ± 0 |

| 16 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 2.2 | >20 | 3.1 | >100 ± 0 |

| 17 | 2-(1-methyl)pyrrolyl | 15.8 | >20 | 4.7 | >100 ± 0 |

| 18 | 5-(3-methyl)pyrazolyl | 7.1 | >20 | 4.6 | >100 ± 0 |

Table 2.

CPE Results against a Panel of Orthopoxviruses

| EC50(μM)

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variola | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Example # | Vaccinia | Cowpox | Monkeypox | Camelpox | BUT | BSH |

| 5 | >20 | >20 | >16 | 4.2 | 10 | >20 |

| 7 | 0.5 | 17.2 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.4 |

| 11 | 2.3 | >20 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 3.3 |

| 13 | 0.02 | 1.6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| 14 | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| 15 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

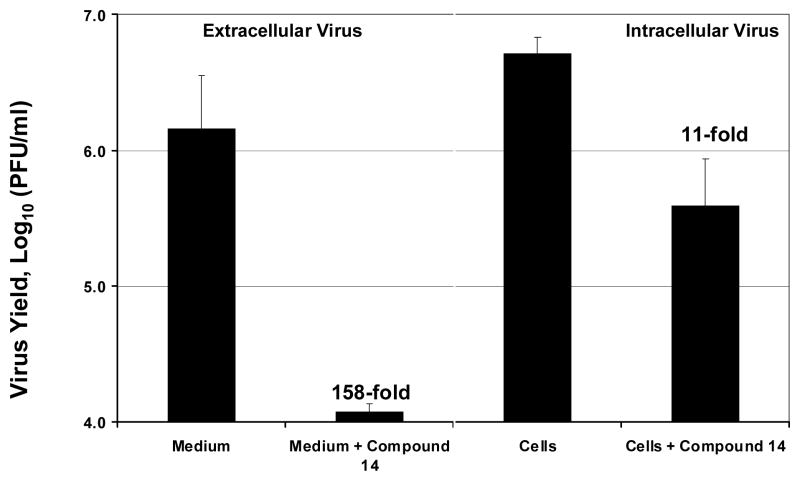

The mechanism of action for the observed activity was systematically uncovered through virus yield and resistance mapping of cowpox drug-resistant variants.8 These studies indicated that compound 14 inhibited formation of extracellular forms of virus. Marker rescue of compound-resistant cowpox virus variants localized the reduced susceptibility phenotype to the cowpox virus V061 gene, which is homologous to the vaccinia virus F13L gene. This gene encodes a major envelope protein necessary for the formation and egress of extracellular virus particles. Based on these data, and the fact that compound 14 inhibited plaque formation and virus-induced CPE, the effects of compound 14 on virus egress were examined. Virus yield assays were conducted to measure the amount of intracellular and extracellular virus produced in the presence and absence of compound. The results show that compound 14 reduced extracellular virus titers by approximately 158-fold at 24 hours post-infection while reducing the level of intracellular virus titers relative to untreated controls by 11-fold (Figure 3). These results suggest that compound 14 inhibits extracellular virus formation, and are consistent with F13L being the target of antiviral activity. Furthermore, orthopoxvirus selectivity for compound 14 was confirmed in plaque reduction EC50’s >40 μM against other double-stranded DNA viruses (HSV-1, CMV), and RNA viruses (RSV, BVDV, rotavirus).8

Figure 3.

Inhibition of virus egress by compound 14.a

a) BSC-40 cells were infected with 2 pfu/cell of vaccinia virus strain IHD-J and incubated in the presence and absence of 5uM compound 14. At 24 h post-infection, extracellular virus in the medium and cell-associated virus were quantified by plaque assay. Y axis = log10 virus titer. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of triplicate virus yield determinations.

With SAR defined, we began to examine the pharmacokinetics for these inhibitors. Metabolic stability was measured in vitro by incubating compounds 13 and 14 with microsomal (S-9) extracts derived from the livers of multiple animal species and measuring the loss of parent compound by LC/MS. From the decay curve, the half life of compound was calculated and used as a measure of metabolic stability. As shown in Table 3, the metabolic stability (T½) for each compound was greater than 200 minutes. Ultimately, the superior human S-9 stability for compound 14 led to the advancement of this compound into pharmacokinetic (PK) studies.

Table 3.

S9 Metabolic Stability of Compounds 13 and 14.

| T½ (min)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Rat | Mouse | Dog | Monkey | Human |

| 13 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | 57 |

| 14 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 | >200 |

NADPH added

Oral and intravenous administration of compound 14 in rats demonstrated oral bioavailability of 31% with a clearance rate and plasma drug exposure (area under the concentration time curve (AUC)) at levels above the in vitro EC50 values (Table 4). Subsequent dose ranging and tolerability studies in mice supported proof-of-concept animal studies. Compound 14 was tested in 3 murine models of orthopoxvirus disease and demonstrated efficacy comparable to cidofovir8. Compound 14 was found to be safe and well tolerated after 28-day repeat dosing in mice and cynomolgus macaques with no observable adverse effect levels (NOAEL) of 2000 mg/kg and 600 mg/kg, respectively. Based on the PK profile and safety profile, compound 14 (ST-246) is currently being evaluated in human Phase I clinical trials.

Table 4.

Oral Pharmacokinetics of Compound 14 in the Rat at 10 mg/kg (0.75% Methocell/1% Tween).

| Dose= | 2 mg/kg |

| Tmax= | 2.2 h |

| Cmax= | 0.92 μg/mL |

| AUC= | 6.10 μg• h/mL |

| t½= | 4.2 h |

| CL= | 0.52 L/h/kg |

| Vss= | 0.6 L/kg |

| %F= | 31 |

A series of potent, selective orthopoxvirus inhibitors that act by inhibiting virus egress from infected cells has been discovered. Compound 14 demonstrated favorable PK properties, efficacy in murine models of orthopoxvirus disease following oral administration, and a safety profile that supports use of this compound in humans. SAR around the aryl carboxamide indicates correlation between electron withdrawing substituents and potency. Additional SAR studies around this scaffold will be discussed in a future report.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Victor G. Young and the X-ray Crystallography Laboratory at the U. of Minnesota for the X-ray crystallographic work. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant 1 R43 AI056409-01 to (RJ) and by Public Health Service contracts NO1-AI-30049 and NO1-AI-15439 and grant 1-U54-AI-057157 from the NIAID, NIH. (ERK)

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details of the synthesis and characterization of the orthopoxvirus inhibitors and crystallographic information for compound 13. The information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bray M. Pathogenesis and Potential Antiviral Complications of Smallpox Vaccination. Antiviral Res. 2003;58:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Baker RO, Bray M, Huggins JW. Potential Antiviral Therapeutics for Smallpox, Monkeypox, and other Orthopox Infections. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kern ER. In Vitro Activity of Potential Anti-poxvirus Agents. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) LeDuc JW, Damon I, Relman DA, Huggins J, Jahrling PB. Smallpox Research Activities: U.S. Interagency Collaboration. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:743–745. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lalezari JP, Stagg RJ, Kuppermann BD, Holland GN, Kramer F, Ives DV, Youle M, Robinson MR, Drew WL, Jaffe HS. Intravenous Cidofovir for Peripheral Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in Patients with AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:257–263. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-4-199702150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong X, Smith JL, Chen MS. Effect of Incorporation of Cidofovir into DNA by Human Cytomegalovirus DNA Polymerase on DNA Elongation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:594–599. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alder KA, Ciesla SL, Winegarden KL, Hostetler KY. Increased Antiviral Activity of 1-O-Hexadecyloxypropyl-[2-14C]cidofovir in Human MRC-5 Human Lung Fibroblasts is Explained by Unique Cellular Uptake and Metabolism. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:678–681. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison SA, Alberts B, Ehrenfeld E, Enquist L, Fineberg H, McKnight SL, Moss B, O’Donnell M, Ploegh H, Schmid SL, Walter KP, Theriot J. Discovery of antivirals against smallpox. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(31):11178–11192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403600101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Leitich J, Sprintschnik G. Thermal cycloaddition of maleic anhydride to cycloheptatriene, 7H-benzocycloheptene, and 7H-benzocycloheptene-7,7-dicarbonitrile. [4π +2π] or [2π +2+ 2π] cycloaddition? Chem Ber. 1986;119:1640–1660. [Google Scholar]; (b) Alder K, Jacobs G. The Diene Synthesis. XL. Diene Synthesis with 1,3,5-cycloheptatriene. Chem Ber. 1953;86:1528–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang G, Pevear DC, Davies MH, Collett MS, Bailey T, Rippen S, Barone L, Burns C, Rhodes G, Tohan S, Huggins JW, Baker RO, Buller RLM, Touchette E, Waller K, Schriewer J, Neyts J, De Clercq E, Jones K, Hruby D, Jordan R. An Orally Bioavalable Antipoxvirus Compound (ST-246) Inhibits Extracellilar Virus Formation and protects Mice from Lethal Orthopoxvirus Challenge. J Virol. 2005;79:13139–13149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.13139-13149.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.