Abstract

Objective:

Radiological scoring is particularly useful in rickets, where pre-treatment radiographical findings can reflect the disease severity and can be used to monitor the improvement. However, there is only a single radiographic scoring system for rickets developed by Thacher and, to the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated radiographic changes in rickets based on this scoring system apart from the one done by Thacher himself. The main objective of this study is to compare and analyse the pre-treatment and post-treatment radiographic parameters in nutritional rickets with the help of Thacher's scoring technique.

Methods:

176 patients with nutritional rickets were given a single intramuscular injection of vitamin D (600 000 IU) along with oral calcium (50 mg kg−1) and vitamin D (400 IU per day) until radiological resolution and followed for 1 year. Pre- and post-treatment radiological parameters were compared and analysed statistically based on Thacher's scoring system.

Results:

Radiological resolution was complete by 6 months. Time for radiological resolution and initial radiological score were linearly associated on regression analysis. The distal ulna was the last to heal in most cases except when the initial score was 10, when distal femur was the last to heal.

Conclusion:

Thacher's scoring system can effectively monitor nutritional rickets. The formula derived through linear regression has prognostic significance.

Advances in knowledge:

The distal femur is a better indicator in radiologically severe rickets and when resolution is delayed. Thacher's scoring is very useful for monitoring of rickets. The formula derived through linear regression can predict the expected time for radiological resolution.

Rickets, a metabolic bone disease, is characterized by defective mineralization of newly formed bone matrix owing to a deficiency of vitamin D and/or dietary calcium before epiphyseal fusion.1

Nutritional rickets has rapidly gained public health attention worldwide during the past decade owing to the recent surge of cases, especially in developed countries, where it was thought to have been eradicated. Radiography is crucial for its diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Radiological scoring is particularly useful in rickets, where pre-treatment radiographic findings can reflect the disease severity and can be used during follow-up to monitor the improvement.

However, there is only a single radiographic scoring system for rickets, developed by Thacher et al,2 and, to the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated radiographic changes in rickets based on this scoring system apart from the one done by Thacher himself. The main objective of this study is to compare and analyse the pre- and post-treatment radiographic parameters in nutritional rickets being treated by stoss therapy (single mega-dose of vitamin D) with the help of Thacher's scoring technique so as to determine its usefulness as a tool for monitoring the improvement and to formulate a reliable, accurate, yet cost-effective follow-up regime that can be useful in less developed countries where rickets is endemic.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This longitudinal prospective study was conducted over a 1-year period.

Setting

Patients attending the outpatient department (OPD) of a tertiary care hospital.

Patients and inclusion–exclusion criteria

176 untreated patients with nutritional rickets aged between 6 months and 12 years, diagnosed on the basis of clinical, biochemical and radiological features, were enrolled with written informed consent from the parents. Patients with a history of prematurity, tumour, renal or hepatic disease, intestinal malabsorption, chronic diseases, including tuberculosis, and other bony diseases were excluded.

Intervention

The patients so selected were given a single intramuscular injection of vitamin D (600 000 IU) with oral supplementary calcium (50 mg kg−1) and vitamin D (400 IU per day) until complete radiological resolution along with advice on diet (containing egg, fish and milk) and sunlight exposure (30 min weekly).

Outcome measures

Data pertaining to duration of breast feeding and average sunlight exposure per week were estimated by questionnaire. Average sunlight exposure per week was quantified by asking the parents and the patients regarding the amount of time the patients were exposed to sunlight in a week and the nature of clothing used during the exposure: whether the child was partially dressed (half-shirt and trousers) or completely dressed (full shirt and trousers) or minimally dressed (only in underwear). The daily intake of cow's milk, if any, was quantified by measuring the volume of the container used by the child to drink milk. Radiological scoring was done based on the 10-point scoring system by Thacher et al.2 Follow-up was done at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 1 year with an anteroposterior view of the bilateral wrist and knee joints. Pre- and post-treatment radiological parameters were compared and analysed statistically by using the paired t-test for quantitative data and the χ2 test for qualitative data with the help of SPSS® v. 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Ethics clearance was obtained for the study.

RESULTS

178 patients (78 males and 100 females) with nutritional rickets met the selection criteria and were enrolled in the study. Subsequently, two patients were lost to follow-up and were excluded from the study. The mean age of presentation was 3 years 4 months (range, 6 months to 12 years). Mean sunlight exposure was 9 min per week (range, 0–2 h per week) with 75% of patients having no sunlight exposure and 97% having sunlight exposure of less than 30 min per week. Those who were exposed to sunlight were partially dressed during the exposure. A history of prolonged breast feeding for more than 6 months was found in all the cases, with a mean of 1 year 8 months (range, 8–42 months). The mean radiological score at initial presentation was 6.8 ± 3.2 (range, 1–10) with 43% having a score of 10. About 10% of children achieved complete radiological resolution by 3 weeks, 21% by 6 weeks and 47% by 3 months. By 6 months, all the study subjects had complete radiological resolution (Table 1). All the changes of radiological scores during the follow-up were found to be statistically significant by paired t-test (Table 2). Time for the radiological score to be 0 had a mean of 126.6 days (approximately 4 months), ranging from 20 to 180 days. The first response of resolution was the healing line of rickets found in 83% cases by 3 weeks and in 100% cases by 6 weeks. The order of resolution was as follows: first the cupping disappeared followed by fraying and finally splaying.

Table 1.

Radiological score distribution

| Parameters | Time duration |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 week | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | |

| Mean ± standard deviation radiological score | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | 2.4 ± 2 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| No. of patients having “0 score” (n = 176) | 0 | 18 (10.2) | 37 (21.0) | 82 (46.6) | 176 (100) | 176 (100) | 176 (100) |

Percentage given in brackets.

Table 2.

Mean change of pre- and post-treatment radiological score (by paired t-test)

| Parameters | Time duration |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 weeks | 3–6 weeks | 6–12 weeks | 3–6 months | 6–9 months | 9–12 months | 0–6 weeks | 0–12 weeks | 0–6 months | |

| Mean ± standard deviation change | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 ± 2 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 6.8 ± 3.2 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

It was found that initial radiographic changes were present in the distal ulna in 100% of cases followed by the distal radius in 93% of cases. Distal ulna was the last to heal in about 65% cases overall followed by distal femur in 51% cases (Table 3). However, in all the 75 cases having an initial radiological score of 10, the distal femur was the last to heal. It was also noted that, when the radiological score took more than 12 weeks to resolve, the distal femur was the last to heal in the majority of the cases (83 out of 94 cases).

Table 3.

Variance of anatomical distribution of radiographic changes of ricketsa

| Anatomical location | Study subjects showing radiological changes (n = 176) |

|

|---|---|---|

| At presentation | Disappeared last | |

| Distal radius | 164 (93%) | 27 (15%) |

| Distal ulna | 176 (100%) | 114 (65%) |

| Distal femur | 136 (77%) | 90 (51%) |

| Proximal tibia | 95 (54%) | 5 (3%) |

Multiple response table.

The radiological score at presentation correlated negatively with the initial sunlight exposure (p = 0.000) and the initial daily milk consumption at presentation (p = 0.000), and positively with the duration of breast feeding (p = 0.001). The time taken for the radiological score to resolve completely was found to correlate negatively with daily milk consumption at initial presentation (p = 0.000) and initial sunlight exposure (p = 0.000), and positively with the initial radiological score (p = 0.000) and duration of breast feeding (p = 0.004).

Time for radiological resolution and initial radiological score were linearly associated on regression analysis (Table 4). It was observed that the initial radiological score could explain the variability in the time needed for the radiological score to resolve completely in 90% of cases (adjusted R2 = 0.900). Thus, the time taken for the radiological score to be 0 can be predicted by the formula below with almost 90% accuracy:

Table 4.

Linear regression between initial radiological score (rad 0 week) and time taken for complete radiological resolution

| Constant | Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients | Significance | 95% Confidence interval for B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard error | β | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||

| Rad 0 week | 1.672 | 3.471 | 0.631 | −5.179 | 8.523 | |

| 18.331 | 0.462 | 0.949 | 0.000 | 17.419 | 19.242 | |

Adjusted R2 = 0.900.

Dependent variable: time for radiological score to be 0.

Calculation of formula using linear regression: y = mx + c, where y = time for radiological score to be 0, c = value of constant in column B in the above table, m is the coefficient value for radiological score at 0 week = value of rad 0 week in column B, and x = initial radiological score (rad 0 week).

Hence the formula:

DISCUSSION

Inadequate sunlight exposure at presentation and breast feeding for more than 6 months were found to increase the incidence, severity and recovery time in nutritional rickets. Researchers in Greater New Haven3 conducted a study on 43 children with nutritional rickets, and they also concluded that inadequate sunlight exposure and prolonged breast feeding were the pre-dominant risk factors for rickets. Thus, it is recommended that awareness needs to be generated regarding the role of adequate sunlight exposure (30 min per week)1,2,4–8 and discontinuance of breast feeding beyond 6 months9–14 as a preventive strategy for rickets.

The first radiological sign of response is the appearance of the healing line of rickets, which is a radio-opaque line in the epiphysis signifying that mineralization of the provisional zone of calcification had begun.15 If by 6 weeks this line does not appear then re-evaluation of the patient to confirm the diagnosis is recommended; if the diagnosis remains nutritional rickets then a repeat injection of a mega-dose of vitamin D needs to be given. In our study, the healing line appeared in all the cases by 6 weeks, hence negating the need for a second injection of vitamin D.

In our study, about 47% of patients had complete resolution at 3 months and 100% by 6 months, and there was no re-emergence of the radiological signs during the 1 year of follow-up (Table 1). A study conducted at Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India, revealed complete resolution in 50% of cases by 3 months.16 The time for complete radiological resolution had a mean of 126.6 days (approximately 4 months), ranging from 20 to 180 days. Studies conducted at the University College of Medical Sciences (UCMS) Hospital, New Delhi, India,17 revealed that the time taken for radiological resolution had a mean of 5 months (range, 2–6 months).

All the changes in mean radiological scores during the follow-up were found to be statistically significant by paired t-test (Table 2). This signifies that radiography at every follow-up visit will show significant changes, which can be aptly scored and used for monitoring the outcome. But to avoid multiple radiological exposures during follow-up, it is suggested to repeat radiography once at 6 weeks to look for white lines of rickets and again at the expected time of resolution predicted by the formula (Table 4). This decreases not only the number of radiological exposures but also the cost of treatment (which is especially important in underdeveloped and developing countries where rickets is endemic and a free radiographic facility is not available at all the health centres), and eventually improves the compliance of the patient.

It has been observed that children are more sensitive to the carcinogenic effects of ionizing radiation than adults. Moreover, children have a longer life expectancy than adults, thus increasing the chances of expressing radiation damage.18 Hence, children are to receive minimum radiation exposure whenever possible. Therefore, in view of reducing the cost of therapy and minimizing radiation exposure, only anteroposterior radiographs of the wrist are recommended for both diagnosis and follow-up in rickets as the distal ulna was found to have characteristic radiographic signs of rickets in 100% of cases at initial presentation and was also the last to heal in a maximum number of cases (65%). Studies conducted at the UCMS Hospital17 also concluded the same. However, when the initial radiological score was 10 or resolution time exceeded 3 months, the distal femur was the last to heal in 100% and 88% of cases, respectively; thus establishing it as a better indicator for follow-up (Table 3).

It was found that the time for radiological resolution and initial radiological score were linearly associated on regression analysis, implying that radiologically more severe rickets took a longer time to heal. A formula was also derived based on the linear regression analysis which would predict the expected time for complete radiological resolution from the value of initial radiological score to an accuracy level of 90%. The formula is as follows:

The formula is simple, easy to remember and a fairly accurate one that can be used by physicians in the OPD to give the patient's parents the prognosis regarding the expected time for complete radiological resolution, as well as to time the follow-up. For example, if the initial radiological score is 8, then, according to the formula, the time required for the radiological resolution will be (18.3 × 8) + 1.7 = 148.1 days (i.e. 21 weeks, approximately). So, if the parents enquire about the expected time for radiological resolution, the physician can comment that the child is expected to be fully healed radiologically by 21 weeks. To decrease the amount of radiation exposure of the child, the physician can also ask the patient to come for follow-up once at 6 weeks to look for the white line of rickets (to ensure that the child is responding to treatment) and then directly after 21 weeks (to check whether healing is complete or not). Therefore, this formula may be used to alleviate the need for unnecessary repeating of radiography during follow-up, thus decreasing the radiation exposure to the child and the cost of therapy. Although the formula is capable of predicting correctly the time for radiological resolution in 90% of cases as per the linear regression analysis (adjusted R2 = 0.900), which makes it fairly accurate, validation of this formula on other populations is recommended. (Radiographs of a representative case are enumerated in Figures 1–5; the radiographs shown in the figures are from a single patient showing how radiological healing occurred with time.)

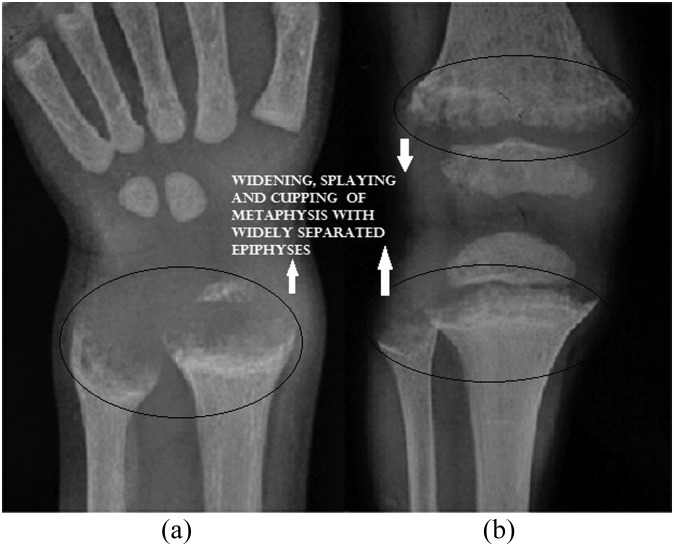

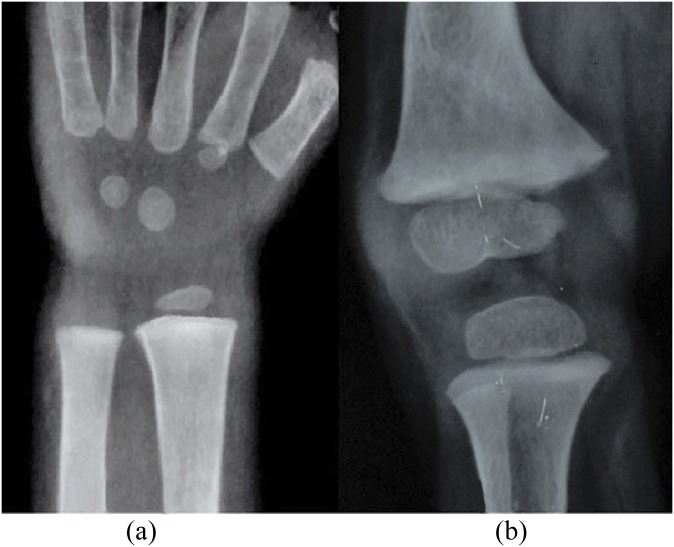

Figure 1.

(a) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the wrist at initial presentation; score 2 + 2 = 4. (b) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the knee at initial presentation; score 3 + 3 = 6. Total score = 10. Metaphyseal cupping, fraying, splaying and epiphyseal separation is evident.

Figure 5.

(a) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the wrist at 6 months; score 0 + 0 = 0. (b) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the knee at 6 months; score 0 + 0 = 0. Complete healing of metaphyses and epiphyses of radius, ulna, femur and tibia evident. Total score = 0. Time taken for resolution = 180 days. Expected time for resolution as predicted by the formula:

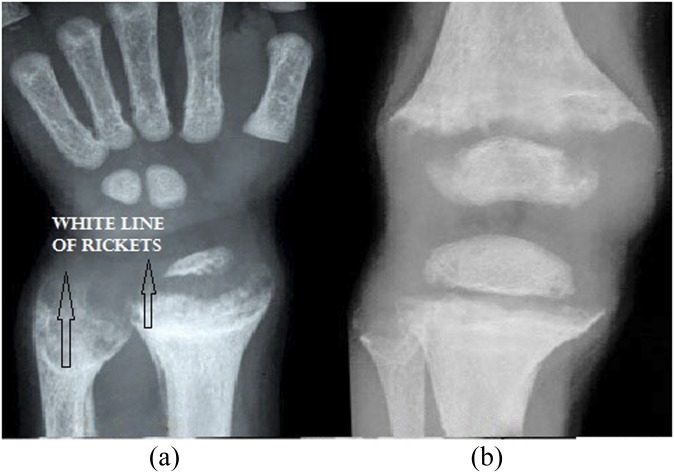

Figure 2.

(a) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the wrist at 3 weeks; score 2 + 2 = 4. Healing line of rickets is evident. (b) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the knee at 3 weeks; score 3 + 2 = 5. Total score: 9. White line of rickets is evident in Figure 2a.

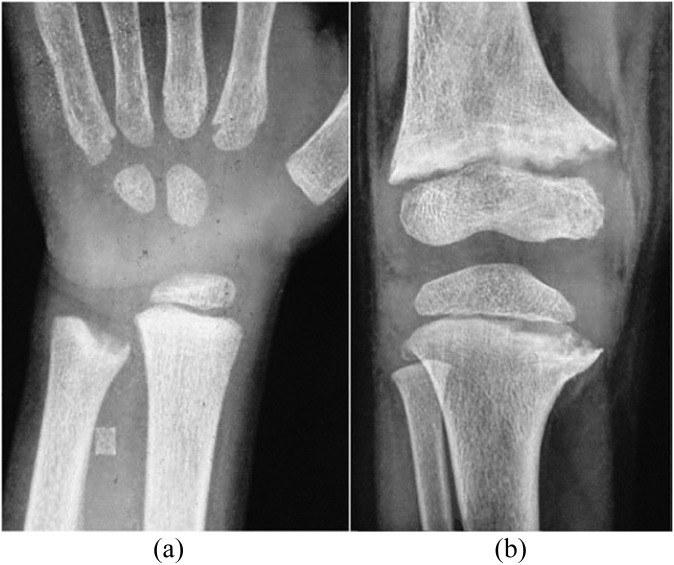

Figure 3.

(a) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the wrist at 6 weeks; score 1 + 0 = 1. (b) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the knee at 6 weeks; score 2 + 0.5 = 2.5. Total score: 3.5.

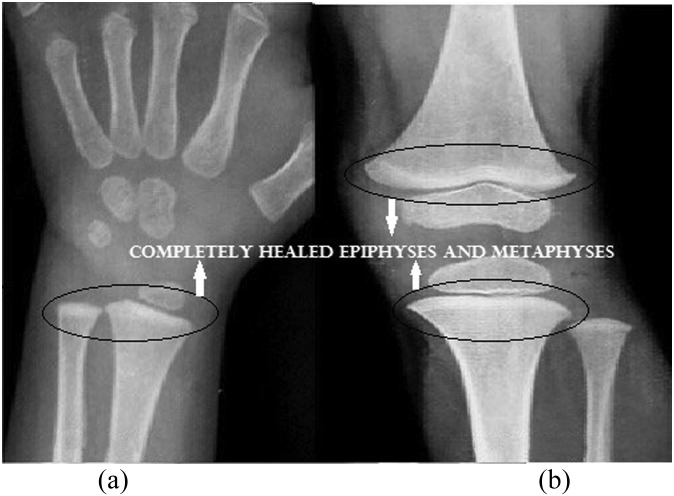

Figure 4.

(a) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the wrist at 3 months; score 0 + 0 = 0. (b) Anteroposterior view radiograph of the knee at 3 months; score 1 + 0 = 1. Total score: 1.

CONCLUSION

Thus, it can be concluded that the distal ulna can be used as the radiological indicator for diagnosis and follow-up in nutritional rickets, except in radiologically severe cases (with a score of 10 or taking longer than 3 months to heal), where the distal femur was a better radiological indicator. Thacher's 10-point scoring system is a very useful tool for assessing the severity of nutritional rickets and its follow-up. The formula derived through linear regression can predict the time of expected radiological resolution that can be used to give the patient's parents the prognosis as well as to decrease the cost of therapy and the number of radiological exposures.

What is known about the subject

The distal ulna is the most specific radiological indicator for completion of radiological healing in nutritional rickets. Thacher's scoring system is the only system to grade radiological changes that aids in monitoring improvement. However, no prospective studies have evaluated its effectivity.

What this study adds

The distal femur is a more specific indicator in radiologically severe rickets and when resolution is delayed. Thacher's scoring is very useful for monitoring of rickets. The formula derived through linear regression can predict the expected time for radiological resolution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holick MF. Mineral and vitamin D adequacy in infant fed human milk or formula between 6 and 12 months of age. J Pediatr 1994; 117: 134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Pettifor JM, Lawson JO, Manaster BJ, Reading JC, et al. Radiographic scoring method for the assessment of the severity of nutritional rickets. J Trop Paeditr 2000; 46: 132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucia MCD, Mitnick ME, Carpenter TO. Nutritional rickets with normal circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a call for reexamining the role of dietary calcium intake in North American infants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 3539–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettifor JM. Vitamin D &/or calcium deficiency rickets in infants & children a global perspective. Indian J Med Res 2008; 127: 245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 266–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones G, Dwyer T. Bone mass in prepubertal children: gender differences and the role of physical activity and sunlight exposure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 4274–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.12.5353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid IR, Gallagher DJA, Bosworth J. Prophylaxis against vitamin D deficiency in the elderly by regular sunlight exposure. Age Ageing 1986; 15: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato Y, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K. Amelioration of osteoporosis and hypovitaminosis D by sunlight exposure in hospitalized, elderly women with Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20: 1327–33. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartner LM, Greer FR; Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition. American Academy of Pediatrics. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: new guidelines for vitamin D intake. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 908–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhowmick SK, Johnson KR, Rettig KR. Rickets caused by vitamin D deficiency in breastfed infants in the southern United States. Am J Dis Child 1991; 145: 127–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eugster EA, Sane KS, Brown DM. Minnesota rickets: need for a policy change to support vitamin D supplementation. Minn Med 1996; 79: 29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edidin DV, Levitsky LL, Schey W, Dumbovic N, Campos A. Resurgence of nutritional rickets associated with breast-feeding and special dietary practices. Pediatrics 1980; 65: 232–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomashek KM, Nesby S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, Powell KE, Parashar UD, et al. Nutritional rickets in Georgia. Pediatrics 2001; 107: E45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mughal MZ, Salama H, Greenaway T, Laing I, Mawer EB. Lesson of the week: florid rickets associated with prolonged breast feeding without vitamin D supplementation. BMJ 1999; 318: 39–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimitri P, Bishop N. Rickets. Paediatr Child Health 2007; 17: 279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal V, Seth A, Marwaha RK. Management of nutritional rickets in Indian children: a randomized controlled trial. J Trop Pediatr 2013; 59: 127–33. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal A, Gulati D. Early adolescent nutritional rickets. J Orthop Surg 2009; 17: 340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinerman RA. Cancer risks following diagnostic and therapeutic radiation exposure in children. Pediatr Radiol 2006: 36: 121–5. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0191-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]