Abstract

Objective:

To investigate two new methods of using computer-aided detection (CAD) system information for the detection of lung nodules on chest radiographs. We evaluated an interactive CAD application and an independent combination of radiologists and CAD scores.

Methods:

300 posteroanterior and lateral digital chest radiographs were selected, including 111 with a solitary pulmonary nodule (average diameter, 16 mm). Both nodule and control cases were verified by CT. Six radiologists and six residents reviewed the chest radiographs without CAD and with CAD (ClearRead +Detect™ 5.2; Riverain Technologies, Miamisburg, OH) in two reading sessions. The CAD system was used in an interactive manner; CAD marks, accompanied by a score of suspicion, remained hidden unless the location was queried by the radiologist. Jackknife alternative free response receiver operating characteristics multireader multicase analysis was used to measure detection performance. Area under the curve (AUC) and partial AUC (pAUC) between a specificity of 80% and 100% served as the measure for detection performance. We also evaluated the results of a weighted combination of CAD scores and reader scores, at the location of reader findings.

Results:

AUC for the observers without CAD was 0.824. No significant improvement was seen with interactive use of CAD (AUC = 0.834; p = 0.15). Independent combination significantly improved detection performance (AUC = 0.834; p = 0.006). pAUCs without and with interactive CAD were similar (0.128), but improved with independent combination (0.137).

Conclusion:

Interactive CAD did not improve reader performance for the detection of lung nodules on chest radiographs. Independent combination of reader and CAD scores improved the detection performance of lung nodules.

Advances in knowledge:

(1) Interactive use of currently available CAD software did not improve the radiologists' detection performance of lung nodules on chest radiographs. (2) Independently combining the interpretations of the radiologist and the CAD system improved detection of lung nodules on chest radiographs.

Chest radiography can be considered the workhorse of the radiology department. It is being used for the detection and diagnosis of multiple diseases, including lung nodules, which may represent early lung cancer. Since a chest radiograph is a two-dimensional image, overprojection of multiple anatomical structures is inevitable. This so-called anatomical noise substantially impedes interpretation of chest radiographs. Multiple studies have shown that a substantial amount of lung cancers are missed, ranging from 19% to 26%,1,2 and even up to 90%.3–5 More recent studies have shown that the problem of missing lung nodules is still present with the most modern digital radiographic technology.6,7 Abnormalities can be missed as a result of inadequate search, perception errors or interpretation errors. It has been stated that interpretation by the radiologist is the most important factor for missing lung cancer on chest radiographs.8,9

To reduce miss rates, computer-aided detection (CAD) systems have been developed. Thus far, all studies dealing with chest radiography apply CAD as a second reader to the radiologist, meaning that the CAD marks are made available only after the radiologist has made a primary review. It remains the reader's discretion to accept or disregard the CAD marks. Results of these studies were contradictory: some found an increased accuracy for the detection of lung nodules,10–12 whereas other studies reported an increase in sensitivity only at the expense of loss in specificity.13–16 One problem ameliorating the potential of CAD is the radiologist's limited ability to reliably discriminate between true-positive (TP) and false-positive (FP) CAD marks.

We therefore decided to explore alternative methods of using CAD information. First, we used CAD interactively. In the interactive mode, CAD marks remained hidden unless the radiologist queried a position in the image by clicking with the mouse on that location. If a CAD mark was present in this location, it was shown to the radiologist together with a score of suspicion. Such an interactive CAD system had been shown to be beneficial in chest radiography in an observer study that only used non-radiologists.17 Second, we computed a mathematical combination of reader and CAD scores. With this method, observers did not need to view the CAD marks at all during their reading of the images, but a mathematical combination of the reader and the CAD scores was computed afterwards. Both methods have been reported to outperform the use of CAD as a second reader for lesion detection in mammograms.18–20

The purpose of this observer study was to test the impact of these two alternative methods of using CAD information on nodule detection on chest radiographs. To optimize baseline performance without CAD, digitally bone-suppressed images (BSIs) were added to the original chest radiographs. BSIs have been shown to improve accuracy for the detection of focal lesions on chest radiographs;21–24 a further increase in detection performance beyond that of BSIs by adding CAD has also been documented.25

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data

Chest radiographs were retrospectively selected from image archives in one academic and three non-academic hospitals. All images were derived from clinically indicated examinations. The selection of study images and study set-up was approved by the institutional review board.

111 chest radiographs of patients with a solitary lung nodule of size 5–35 mm were selected for our study. Both posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiographs were available. All abnormalities were confirmed by a CT scan less than 3 months from the chest radiograph. In the same age range as the patients with a nodule, 189 patients with normal PA and lateral chest radiographs were selected as controls. The absence of lung nodules in normal patients was ascertained by a negative CT scan within 6 months of the chest radiograph. Both nodule cases and control chest radiographs showed signs of chronic pulmonary obstructive disease but not of other parenchymal pathology.

Conspicuity of the 111 lung nodules was scored by an expert radiologist and the clinical researcher in consensus, to ascertain a wide range in conspicuity of the nodules. Thick coronal reconstructions of the CT scan were used to annotate the nodules' exact location on the radiograph. Nodules needed to be visible on the PA radiograph but could be more pronounced on the lateral image.

Image acquisition

All chest radiographs were obtained with a digital technique using storage phosphor plates (CR; Agfa, Mortsel, Belgium), selenium drum (Thoravision; Philips Medical Systems, Hamburg, Germany) and flat panel detector DR systems (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany; Hologic® Inc., Bedford, MA). Image processing was applied as recommended by the manufacturers and in use for clinical routine in the various institutions.

CAD software and applications

Computer detection output was generated by a ClearRead +Detect™ 5.2 (Riverain Technologies, Miamisburg, OH). This CAD system is optimized to detect nodules between 9 and 30 mm in the PA radiograph, although larger and smaller nodules also could get marked. CAD marks were displayed as contours along the lesions' borders. The contours were accompanied by a displayed likelihood score ranging from 0 (low suspicion) to 100 (high suspicion). The contours were also colour coded, with green for low suspicion marks (score of 0) gradually changing to red for high suspicion marks (score of 100) (Figure 1). BSIs were computed by a ClearRead BSI 2.4 (Riverain Technologies). The BSIs can be generated from every digital frontal radiograph, and no special hardware or extra radiation exposure is required. The BSIs have the same gradation and contrast characteristics as the original radiographs. Both software products are commercially available and have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

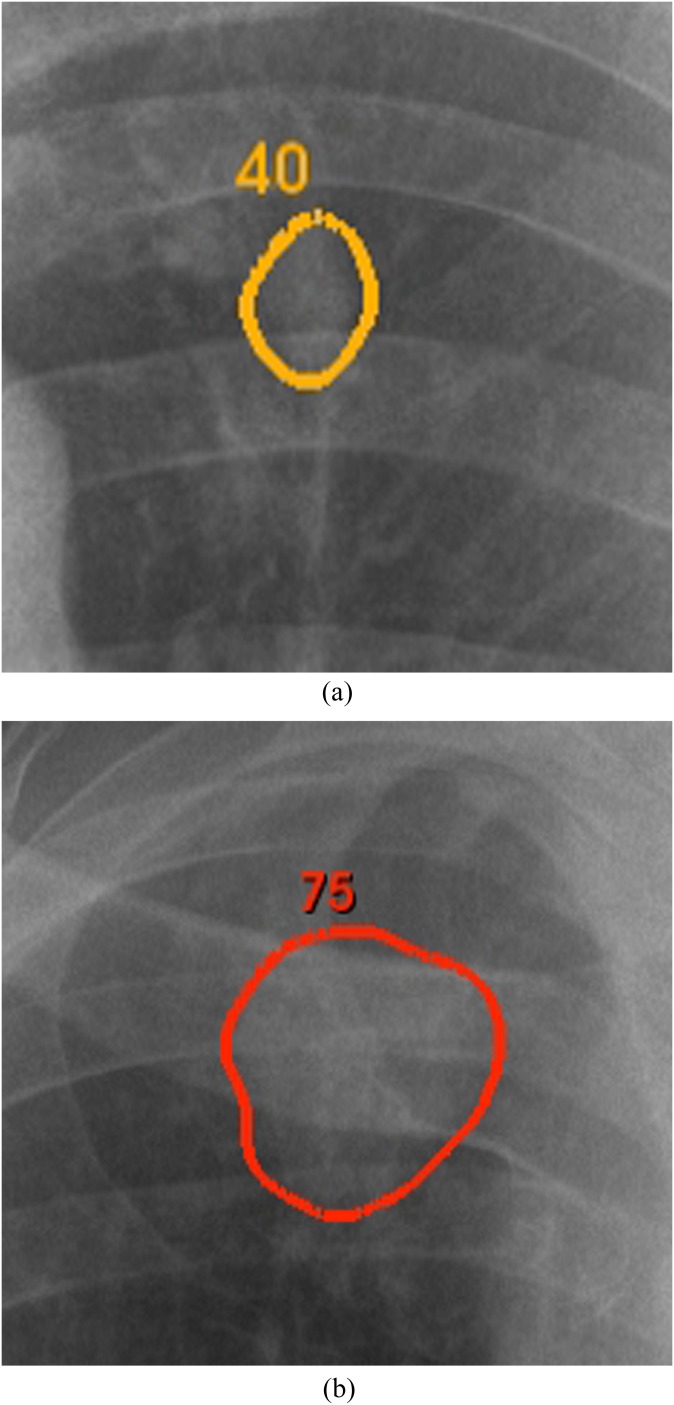

Figure 1.

Two examples of displayed computer-aided detection (CAD) marks (enlarged). The CAD marks were displayed as colour coded, changing from red (high score and highly suspicious) to green (low score and mildly suspicious), CAD contours of suspicious regions.

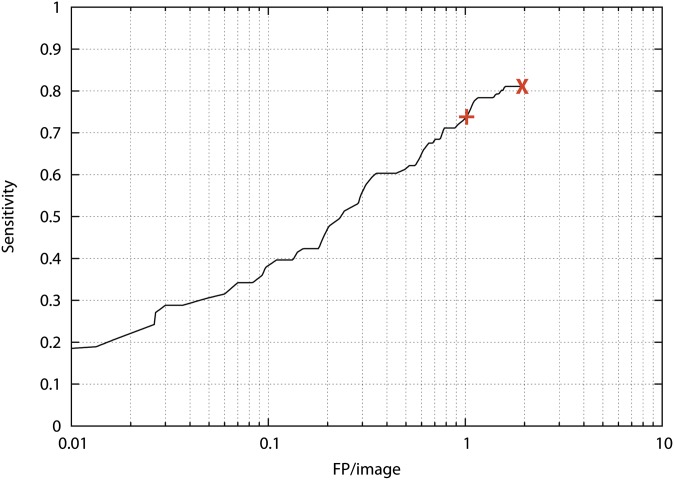

The CAD system was FDA approved as a second reader displaying suspicious lesions above a suspicion score of 35. Using this threshold, CAD achieved a sensitivity of 74% with 1.0 FP per image in our data set.

In this study, we used this software in a modified way: CAD marks were only shown if the particular location was digitally queried by the radiologist, assuming that he/she found a certain feature in this location suspicious. The lower threshold of suspicion was not used, meaning that all CAD marks, including the low suspicion candidates with a higher risk of representing FP lesions, became available but only if queried by the radiologist. Applying no threshold on the CAD system, CAD achieved a sensitivity of 81% at 1.9 FP per image (Figure 2). CAD marks were also displayed differently: with their colour score and colour coded-contour. They could be displayed on both the original radiograph and the BSI.

Figure 2.

Free response receiver operating characteristics curve of the computer-aided detection (CAD) system on our data set. +, normal clinical threshold of the CAD system at a sensitivity of 74% at 1.0 false positive (FP) per image on this case set; X, threshold applied for the interactive CAD system: sensitivity of 81% at 1.9 FP per image for this case set.

Reading methodology

The chest radiographs were read in two reading sessions by six radiologists (years of experience ranging from 3 to 17 years) and six residents [one second-year resident (RW), one third-year resident (MB), three fourth-year residents (EK, AT and IS) and one fifth-year resident (MS)]. In reading session 1, readers reviewed the images without CAD but with BSIs. In reading session 2, readers reviewed the same cases with the additional help of the interactive CAD system. Reading sessions were counterbalanced over the readers, and cases were read in different randomized order. A minimum time delay of 1 week was taken into account between the reading sessions. BSIs were available at all times. The BSI was stacked behind the original radiograph. Readers could toggle between the two images with a key on the keyboard.

Cases were reviewed on a 30-inch Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine calibrated monitor (Flexscan SW3031W; Eizo, Ishikawa, Japan) in a darkened room. The screen had a resolution of 2560 × 1600 pixels, which was large enough to review both PA and lateral images side by side. Commonly used processing tools were available, including zoom in/out, adjustment of window and level and greyscale inversion, and could be applied as warranted by the readers. Readers were able to mark and score multiple suspicious regions on the chest radiograph. Location information on a pixel level and the suspicion scores were stored digitally.

In reading session 2, with the interactive CAD system, readers could click on suspicious regions on the chest radiograph. If the CAD system had marked this region, the CAD mark became visible on demand, accompanied by a score of suspicion. If no CAD mark was available for that position, no score was displayed. The case review system digitally monitored the number of clicks and the location of the clicks.

Reading times per case were digitally recorded, counting from the start of evaluation of the case until the saving of the scores. For analysis, we used median reading times to filter out the effect of long reading caused by interruptions of the reading sessions. 2 min without any mouse movement was considered as idle time and removed from the analysis of reading times.

Before the start of the study, readers were instructed about the use of the review system. A set of 40 training cases containing both nodule and normal cases was used to familiarize the observers with the workflow and the interactive CAD system. In this training session, instant feedback was given by the clinical researcher.

Statistical analysis

Multireader multicase jackknife alternative free response receiver operating characteristics (ROC) was used for statistical analysis. A maximum of one finding per image was used for analysis. For abnormal images, this was the highest TP finding taking location into account. For normal images, this was the highest FP finding of the observer if more than one FP was reported. With this analysis, observers were not rewarded for marking an FP lesion in an abnormal image. A finding was considered TP when the finding was within 1 cm of the centre of the ground truth annotation. The area under the ROC curve was calculated using the trapezoidal/Wilcoxon method. Partial area under the alternative free response receiver operating characteristics (AFROC) curve at an interval of 0.0–0.2, which reflects the sensitivity at a high specificity range, was compared for the two reading sessions (without and with interactive CAD). p-values were calculated for the whole area under the curve (AUC) using the Dorfman–Berbaum–Metz method.26,27 Significance of difference was reached at p < 0.05.

Besides analysis of the reader findings, we analysed an independent joint interpretation of CAD and each of the individual observers. For this purpose, we averaged the CAD scores and the reader scores at the location of reader findings using a weighting factor. Findings of CAD and those of an observer were combined if they were located within 15 mm of each other. If no CAD mark was present within 15 mm of the reader's finding, a score of 0 was used for the CAD system in the averaging process. We used a simple linear combination of CAD and reader scores to calculate the combined interpretation scores. For this, we calculated an optimal weight for combining CAD and reader scores.

RESULTS

Observer performance

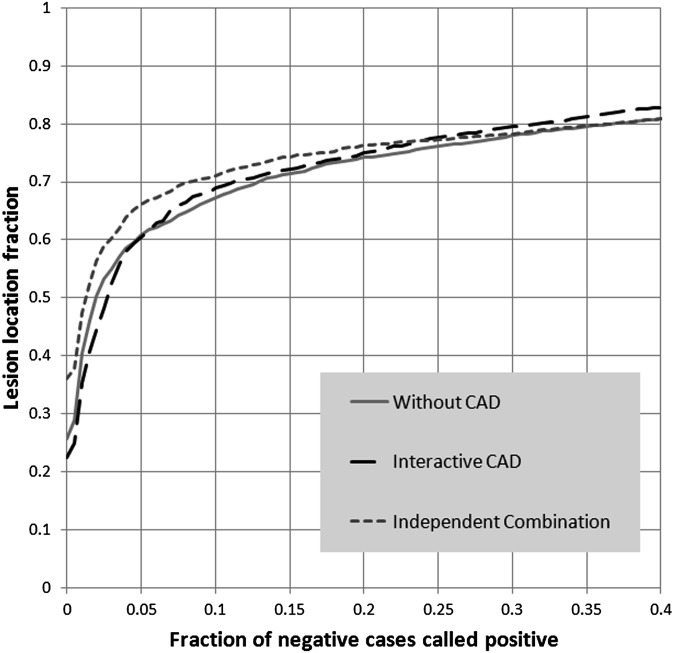

The AUC without CAD was 0.824. The AUC with interactive CAD increased to 0.834 (p = 0.15). The average partial AUC (pAUC) without CAD was 0.128 and did not change for readings with the interactive CAD (0.128) (Figure 3). Individual performances are displayed in Table 1. Residents did improve performance with interactive CAD; however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.17). On average, readers reported 85 lesions without CAD and 88 lesions with the interactive CAD. Without CAD, a mean of 51 FP readings were reported in the normal cases. In the reading session with the interactive CAD 49 FP annotations were reported in the normal cases.

Figure 3.

Alternative free response receiver operating characteristics curve averaged over all readers. Performance without and with computer-aided detection (CAD) was similar. Independent combination of reader and CAD findings resulted in improved performance.

Table 1.

Observer performance

| Observer | AUC |

pAUC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CAD | With CAD | Independent combination | Without CAD | With CAD | Independent combination | |

| Rad 1 | 0.753 | 0.772 | 0.780 | 0.094 | 0.083 | 0.115 |

| Rad 2 | 0.837 | 0.850 | 0.843 | 0.136 | 0.133 | 0.142 |

| Rad 3 | 0.888 | 0.865 | 0.892 | 0.149 | 0.143 | 0.153 |

| Rad 4 | 0.781 | 0.792 | 0.783 | 0.120 | 0.120 | 0.121 |

| Rad 5 | 0.900 | 0.891 | 0.908 | 0.156 | 0.152 | 0.165 |

| Rad 6 | 0.859 | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.143 | 0.137 | 0.148 |

| Average rad (SD) | 0.836 (±0.06) | 0.839 (±0.05) | 0.845 (±0.05) | 0.133 (±0.02) | 0.128 (±0.02) | 0.141 (±0.02) |

| Res 1 | 0.834 | 0.844 | 0.842 | 0.125 | 0.132 | 0.133 |

| Res 2 | 0.834 | 0.832 | 0.834 | 0.137 | 0.134 | 0.137 |

| Res 3 | 0.850 | 0.849 | 0.855 | 0.142 | 0.141 | 0.147 |

| Res 4 | 0.746 | 0.802 | 0.762 | 0.112 | 0.113 | 0.124 |

| Res 5 | 0.847 | 0.845 | 0.853 | 0.131 | 0.135 | 0.138 |

| Res 6 | 0.759 | 0.804 | 0.787 | 0.091 | 0.110 | 0.116 |

| Average res (SD) | 0.811 (±0.05) | 0.829 (±0.02) | 0.822a (±0.04) | 0.123 (±0.02) | 0.128 (±0.01) | 0.133 (±0.01) |

| Average all (SD) | 0.824 (±0.05) | 0.834 (±0.03) | 0.834b (±0.05) | 0.128 (±0.02) | 0.128 (±0.02) | 0.137 (±0.02) |

AUC, area under the curve; CAD, computer-aided detection; pAUC, partial area under the curve at a specificity between 80% and 100% for the individual observers; Rad, radiologist; Res, resident; SD, standard deviation.

p = 0.04.

p = 0.006.

Interactive computer-aided detection system

The CAD system contained 90/111 (81%) TP marks and 594 (366 in normal cases) FP marks (Figure 2). Most FP marks were induced by hilar vessels or the anterior contour of the first rib. Reading time with interactive CAD was on average 3 s per case longer than the reading time without CAD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median reading times in seconds

| Observer | Without CAD | With CAD |

|---|---|---|

| Rad 1 | 17 | 23 |

| Rad 2 | 24 | 25 |

| Rad 3 | 13 | 16 |

| Rad 4 | 11 | 14 |

| Rad 5 | 37 | 41 |

| Rad 6 | 31 | 43 |

| Res 1 | 23 | 28 |

| Res 2 | 27 | 31 |

| Res 3 | 20 | 24 |

| Res 4 | 27 | 31 |

| Res 5 | 26 | 27 |

| Res 6 | 16 | 14 |

| Average (SD) | 23 (±7.6) | 26 (±9.4)a |

CAD, computer-aided detection; Rad, radiologist; Res, resident; SD, standard deviation.

p = 0.003 (paired t-test).

Interactive CAD was used differently per observer. The total number of clicks per observer ranged from 53 to 2624 clicks for the whole case set. On average, observers invoked 143 of the 684 CAD marks. All readers visualized fewer FP marks (84/594 on average) than normally would be prompted by CAD if installed with a threshold of 35 as recommended by the manufacturer (n = 299). On average, 59 TP CAD marks were clicked, of which 57 were accepted and marked by the radiologists. On average, another 20 lesions, mainly the more obvious portion of the lesions, were found without querying the CAD mark. More detail about the usage of interactive CAD can be found in Table 3 and Figure 4.

Table 3.

Observer clicks

| Observer | Total clicks | CAD marks clicked | Detected lesions |

Missed lessions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With CAD display | Without CAD display | No CAD mark available | Total | With CAD display | Without CAD display | No CAD mark available | Total | |||

| Rad 1 | 285 | 53 | 17 | 66 | 9 | 92 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 19 |

| Rad 2 | 707 | 158 | 67 | 8 | 12 | 87 | 2 | 13 | 9 | 24 |

| Rad 3 | 326 | 116 | 42 | 33 | 13 | 88 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 23 |

| Rad 4 | 851 | 193 | 73 | 2 | 8 | 83 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 28 |

| Rad 5 | 2624 | 293 | 72 | 10 | 14 | 96 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 15 |

| Rad 6 | 53 | 2 | 0 | 79 | 12 | 91 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Res 1 | 893 | 195 | 78 | 4 | 9 | 91 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 20 |

| Res 2 | 590 | 138 | 68 | 3 | 9 | 80 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 31 |

| Res 3 | 1061 | 115 | 62 | 8 | 12 | 82 | 3 | 17 | 9 | 29 |

| Res 4 | 1006 | 192 | 77 | 6 | 8 | 91 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| Res 5 | 709 | 165 | 61 | 18 | 9 | 88 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 23 |

| Res 6 | 323 | 97 | 65 | 8 | 9 | 82 | 0 | 17 | 12 | 29 |

| Average | 786 | 143 | 57 | 20 | 10 | 88 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 23 |

CAD, computer-aided detection; Rad, radiologist; Res, resident

This table shows the number of clicks and queried true-positive and false-positive CAD marks per observer. The table differentiates the number of detected and missed lesions without and with display of a CAD mark (clicked CAD marks by the observer).

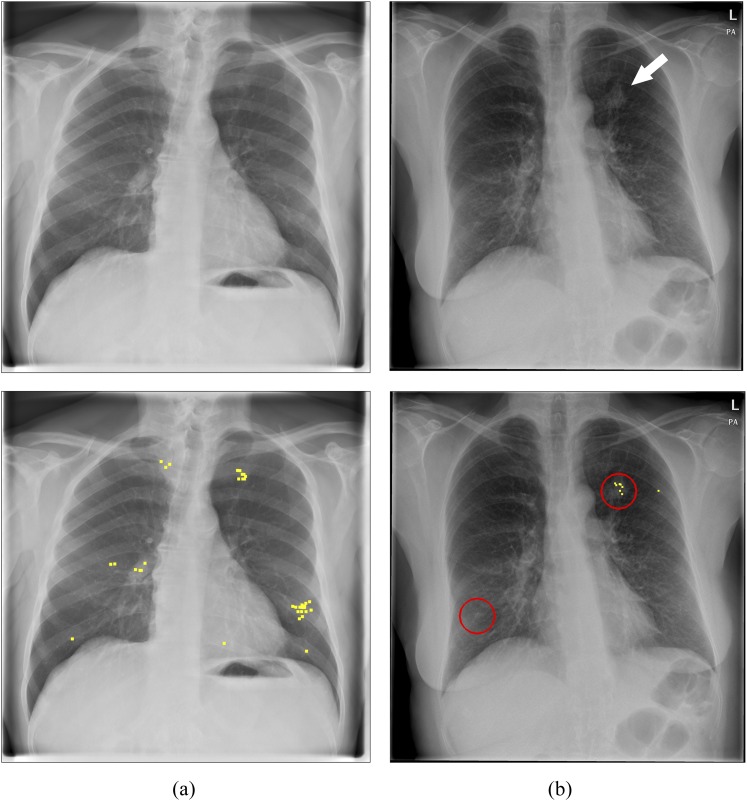

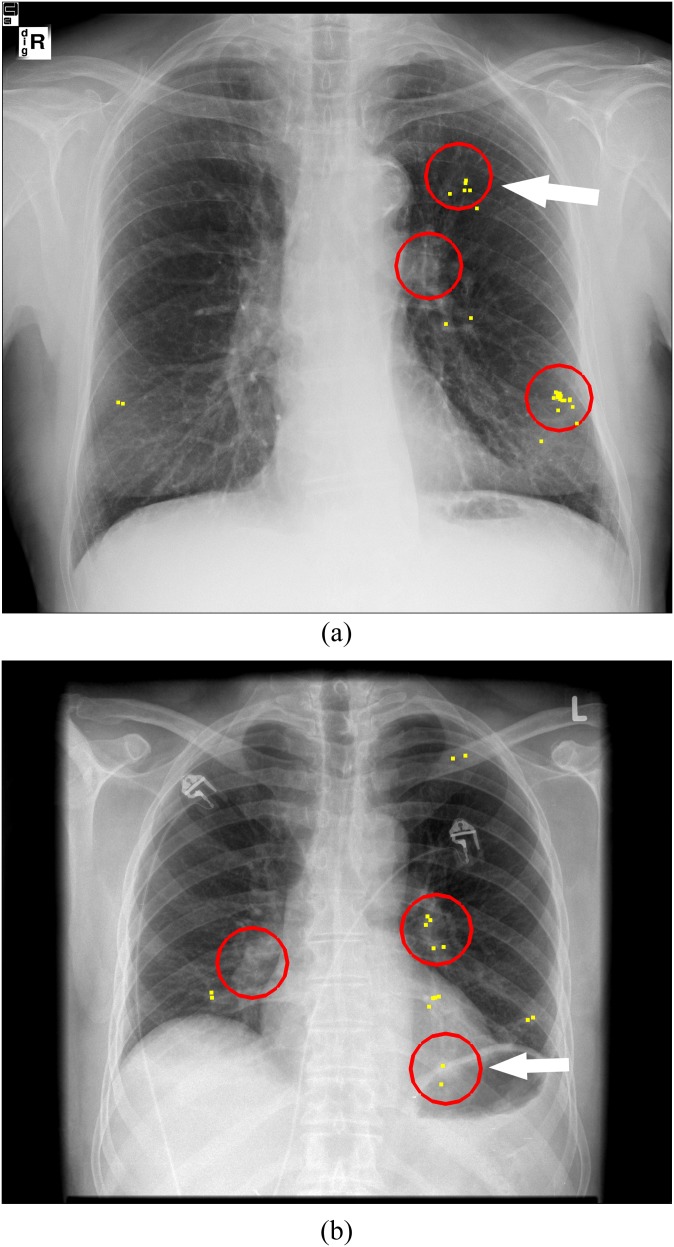

Figure 4.

Examples of interactive use of computer-aided detection (CAD). (a) Normal image, no CAD marks that could be queried. (b) Nodule case with a true-positive CAD mark. Arrow indicates the lesion; circles represent CAD marks that could be queried by the observers; and dots represent all clicks of the 12 observers in the image.

Inclusion of CAD marks with low suspicion scores (1–35) yielded an increase in sensitivity from 74% to 81%, amounting to an extra 8 truly identified nodules by CAD. 59% (on average five per observer) of these eight nodules were reported by the radiologists also without CAD. With the availability of CAD, the radiologists located 63% of these lesions. For the majority of the detected nodules (4/5), the radiologists queried the CAD score. With CAD used interactively, no increase in FP calls was observed in those cases that now yielded a low suspicion score (<35) by CAD analysis and would not contain a CAD mark at the manufacturers' threshold (n = 29). Without CAD, 86 FP calls by the 12 observers were recorded in these cases, and with CAD this number was 69.

Weighted independent combination

Optimal weight in this study for combining CAD and reader score was seen with a weight of 0.39 for CAD and 0.61 for the reader scores. Combination of CAD scores with reader scores on the location of the reader findings showed similar performance to the readings session with interactive CAD with an AUC of 0.834 but was significantly better than the performance of the readers for the readings session without CAD (p = 0.006). The pAUC was the best for independent combination with a pAUC of 0.137. Every observer had the best performance for independent combination compared with reading without CAD and with interactive CAD. Figure 3 shows the AFROC curves for the evaluation without CAD, with interactive CAD and the independent combination. CAD found on average 70 of the 85 lesions that were identified by the observers, forming a second confirmation for these lesions and retaining a high suspicion score in the joint interpretation. CAD did not mark 29 of the 51 FP findings by the observers, bringing down the suspicion of these findings and increasing the specificity of the joint interpretation. Another 10 FP locations per reader were also marked by CAD, but with a lower suspicion than the observers, causing a decrease in suspicion for these findings in the joint interpretation.

CAD found 38 lesions that were missed by at least 1 observer and thus could offer extra information if all CAD mark locations (not only reader-located findings) were taken into account.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we explored two alternative ways to apply CAD as support for detection of pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs. The motivation behind the interactive use of CAD information is to decrease the number of FP calls initiated through CAD candidates. Previous studies had shown that readers have difficulty in differentiating TP from FP CAD marks, leading to either dismissed TP marks or accepted FP ones. A previous study that had included only inexperienced readers (non-radiologists) had shown a positive effect of interactive CAD over prompting CAD for the detection of nodules. For mammography, interactive CAD has yielded a significantly improved detection of masses by radiologists with a larger advantage for the less experienced readers. Results of this study showed a generally lower performance of the residents than that of the radiologists. Only the residents increased in performance using interactive CAD; the difference, however, was not statistically significant.

As expected, interactive CAD succeeded in avoiding FP calls by the observers motivated by CAD candidates. Multiple previous studies have found that CAD prompts an increase in the sensitivity for the detection of nodules but at the expense that radiologists report more FP findings induced by CAD prompts.13–16 Our results now show that, without prompting of CAD marks, readers do not identify many of those areas as suspicious, in which CAD yields FP results.

However, together with the decreased exposure to FP CAD marks, also fewer TP CAD marks were visualized. With CAD used in the traditional way, 82 TP CAD marks would have been prompted for this case set, providing a higher chance of detecting nodules previously missed. For a significant portion of the lesions (n = 20 of 88) that were marked by the observers, they did not ask CAD for feedback, suggesting that their confidence in the presence of a lesion did not need further confirmation by CAD.

The interactive CAD mode gave us the opportunity to classify errors made by the observers based on the clicks in the images. If a lesion was clicked, it was definitely detected. However, if a lesion was not clicked, the observer still could have detected it visually. On average, only 2 lesions were dismissed with review of the TP CAD mark, whereas 11 lesions were not clicked at all (Figure 5). These results suggest that oversight errors may have contributed more to missed lung nodules than interpretation errors, in contrast to the previous literature. These previous papers suggested that decision-making is the main problem in missing lung lesions.8,9 Using an eye-tracking technique, they considered a long dwell time to be a surrogate for visually localizing or detecting a lesion and considered a lesion that was “visually” localized but subsequently not reported as an interpretation fault. Based on that assumption, interpretation faults were considered the underlying reason for the majority of missed lesions. Assuming that, in our study, any area that provoked increased alertness would have resulted in clicking this area to query the CAD mark, we found that many lesions were missed because of oversight rather than interpretation faults. We therefore think that a long dwell time may not necessarily relate to conscious perception of a lesion and, therefore, classification of observer errors based on dwell times may not always be correct.

Figure 5.

Oversight errors. Two examples of missed lung nodules caused by detection errors. (a) Lesion in the left lung not clicked and not marked by 9 of the 12 observers. (b) A retrocardiac lesion that was not queried and marked by 10 of the 12 observers. Arrows indicate the lesion; circles represent computer-aided detection marks that could be queried by the observers; and dots represent all clicks of the 12 observers in the image.

One could argue that a non-clicked lesion indicates that the lesion did not meet the threshold of the observer for asking for CAD feedback, although it might have been detected visually. However, in this study, we did not see a correlation between the quantity of clicks and the number of missed lesions. What percentage of missed lesions can be attributed only to decision errors cannot exactly be determined from our results. The fact that only very few false-negative decisions were made when reviewing a queried TP CAD mark supports the hypothesis that decision-making yields fewer errors than previously assumed. The major drawback of the interactive CAD is the fact that on average around 11 lesions were missed because the area did not trigger a query for the CAD score which would have revealed a TP suspicion score. This large amount of eventually missed lesions represents underused information of CAD.

It has to be noted that readers received only limited training of 40 cases with the interactive system. Such an interactive approach, which is completely novel to the observers, might require more training before it is being used optimally. This is demonstrated by the widely variable use of the interactive CAD system in our study. A very high number of clicks as seen in some readers (>1000) is indicative of a more random selection of query locations in the image rather than using CAD as feedback for specific locations that have provoked at least some degree of suspicion. It remains open whether more training would be able to increase the benefit of the interactive system. A successful implementation of interactive CAD however is only possible if perception errors can also be reduced.

As a second alternative approach, we assessed the effect of independent combination of reader and CAD findings. Our results found that the independent combination had a higher accuracy for the detection of lung nodules than interpretation without CAD. This performance increase was not only realized for the whole reader group but also on an individual reader level and especially at a high specificity range. Even the best observers increased in performance when their interpretations were combined with CAD. Similar results have been previously reported for mammography.20 In this study, we used a similar approach by only combining scores of locations that were detected and marked by the observer. With this approach, no new lesions could be identified, since the combination is restricted to the location of the reader's findings. The improvement is, therefore, solely attributed to a gain in differentiation between TP and FP findings: TP reader findings are strengthened by combining with the CAD score, whereas FP findings by the readers were often not identified by CAD and thus decreased in suspicion. If all CAD marks—thus not only the ones on reader mark locations—are taken into account, a further increase in sensitivity can be expected, but inevitably also many more FP marks would be introduced. The independent combination with CAD shows that there is potential to improve reader performance using the results of the CAD software but without interfering with the reading process. It has to be noted that current FDA approval does not allow for such an application and therefore any clinical usefulness remains speculative at this point. We used this mathematical approach to simulate potential new ways to apply CAD in the future. Rather than using CAD as a second reader, whose results actively have to be accepted or dismissed by the radiologists, we used the CAD output to independently weigh the scores of the radiologists.

Our study has some limitations. First, the study consisted of a selected group of cases with a high prevalence of lung nodules. Moreover, the observers reviewed the images under study conditions in which they were focused on detecting focal abnormalities. This does not reflect the clinical situation. It could be that the problem of oversight in clinical practice is larger, since the search task is often more complex than only finding lung nodules as in our study. Furthermore, results in our study are very dependent on the quality of the CAD system. In this study, we used a system that is inferior to the human observers. It is plausible that the use of an improved CAD system would markedly improve observers' detection performance.

In conclusion, interactive CAD did not improve observer performance for the detection of lung nodules on chest radiographs mainly because sensitivity was not improved. As expected, usage of interactive CAD successfully avoided loss of specificity, which has been seen as a problem in previous studies using CAD prompts. Furthermore, these results indicate that successful implementation of CAD is only possible if it is applied in a way that compensates for perception errors of radiologists. Independent combination of CAD and reader scores demonstrated an increase in accuracy for the detection of lung nodules. This shows that CAD contains important information that might be beneficially used as an adjunct to the observer evaluation without interfering with the reading process itself.

FUNDING

Supported by a research grant from Riverain Technologies, Miamisburg, OH.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge L. Meiss, L. Peters-Bax, M. Snoeren, A. Tiehuis, R. Wittenberg, E. Koedam and L. Quekel for their participation in the observer study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austin JH, Romney BM, Goldsmith LS. Missed bronchogenic carcinoma: radiographic findings in 27 patients with a potentially resectable lesion evident in retrospect. Radiology 1992; 182: 115–22. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quekel LG, Kessels AG, Goei R, van Engelshoven JM. Miss rate of lung cancer on the chest radiograph in clinical practice. Chest 1999; 115: 720–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhm JR, Miller WE, Fontana RS, Sanderson DR, Uhlenhopp MA. Lung cancer detected during a screening program using four-month chest radiographs. Radiology 1983; 148: 609–15. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6308709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heelan RT, Flehinger BJ, Melamed MR, Zaman MB, Perchick WB, Caravelli JF, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the New York screening program. Radiology 1984; 151: 289–93. doi: 10.1148/radiology.151.2.6324279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monnier-Cholley L, Arrivé L, Porcel A, Shehata K, Dahan H, Urban T, et al. Characteristics of missed lung cancer on chest radiographs: a French experience. Eur Radiol 2001; 11: 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu M, Gotway MB, Lee TJ, Chern M, Cheng H, Ko JS, et al. Features of non-small cell lung carcinomas overlooked at digital chest radiography. Clin Radiol 2008; 63: 518–28. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Hoop B, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Gietema HA, de Jong PA, van Ginneken B, van Klaveren RJ, et al. Screening for lung cancer with digital chest radiography: sensitivity and number of secondary work-up CT examinations. Radiology 2010; 255: 629–37. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundel HL, Nodine CF, Carmody D. Visual scanning, pattern recognition and decision-making in pulmonary nodule detection. Invest Radiol 1978; 13: 175–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning DJ, Ethell SC, Donovan T. Detection or decision errors? Missed lung cancer from the posteroanterior chest radiograph. Br J Radiol 2004; 77: 231–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kligerman S, Cai L, White CS. The effect of computer-aided detection on radiologist performance in the detection of lung cancers previously missed on a chest radiograph. J Thorac Imaging 2013; 28: 244–52. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31826c29ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Ma D, He W. Assessing the use of digital radiography and a real-time interactive pulmonary nodule analysis system for large population lung cancer screening. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: e451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Beek EJR, Mullan B, Thompson B. Evaluation of a real-time interactive pulmonary nodule analysis system on chest digital radiographic images: a prospective study. Acad Radiol 2008; 15: 571–5. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meziane M, Obuchowski NA, Lababede O, Lieber ML, Philips M, Mazzone P. A comparison of follow-up recommendations by chest radiologists, general radiologists, and pulmonologists using computer-aided detection to assess radiographs for actionable pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196: W542–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boo DW, Uffmann M, Weber M, Bipat S, Boorsma EF, Scheerder MJ, et al. Computer-aided detection of small pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs: an observer study. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 1507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Hoop B, de Boo DW, Gietema HA, van Hoorn F, Mearadji B, Schijf L, et al. Computer-aided detection of lung cancer on chest radiographs: effect on observer performance. Radiology 2010; 257: 532–40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KH, Goo JM, Park CM, Lee HJ, Jin KN. Computer-aided detection of malignant lung nodules on chest radiographs: effect on observers' performance. Korean J Radiol 2012; 13: 564–71. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.5.564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samulski MRM, Snoeren PR, Platel B, van Ginneken B, Hogeweg L, Schaefer-Prokop C, et al. Computer-aided detection as a decision assistant in chest radiography. In: Manning DJ, Abbey CK, editors. Medical imaging 2011: image perception, observer performance, and technology assessment. Proceedings of the SPIE, vol. 7966. College Park, MD: American Institute of Physics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hupse R, Samulski M, Lobbes MB, Mann RM, Mus R, den Heeten GJ, et al. Computer-aided detection of masses at mammography: interactive decision support versus prompts. Radiology 2013; 266: 123–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samulski M, Hupse R, Boetes C, Mus R, den Heeten G, Karssemeijer N. Using computer aided detection in mammography as a decision support. Eur Radiol 2010; 20: 2323–30. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1821-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karssemeijer N, Otten JDM, Verbeek ALM, Groenewoud JH, de Koning HJ, Hendriks JHCL, et al. Computer-aided detection versus independent double reading of masses on mammograms. Radiology 2003; 227: 192–200. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2271011962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Engelmann R, Pesce LL, Doi K, Metz CE, Macmahon H. Small lung cancers: improved detection by use of bone suppression imaging—comparison with dual-energy subtraction chest radiography. Radiology 2011; 261: 937–49. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, Engelmann R, Pesce L, Armato SG3rd, Macmahon H. Improved detection of focal pneumonia by chest radiography with bone suppression imaging. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 2729–35. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2550-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman MT, Lo SCB, Seibel JC, Bromley CM. Lung nodules: improved detection with software that suppresses the rib and clavicle on chest radiographs. Radiology 2011; 260: 265–73. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11100153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Meiss L, Peters-Bax L, Quekel LGBA, Snoeren MM, et al. Bone suppressed images improve radiologists’ detection performance for pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. Eur J Radiol 2013; 82: 2399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schalekamp S, van Ginneken B, Koedam E, Snoeren MM, Tiehuis AM, Wittenberg R, et al. Computer aided detection improves detection of pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs beyond the support by bone suppressed images. Radiology 2014; in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorfman DD, Berbaum KS, Metz CE. Receiver operating characteristic rating analysis: generalization to the population of readers and patients with the jackknife method. Invest Radiol 1992; 27: 723–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roe CA, Metz CE. Variance-component modeling in the analysis of receiver operating characteristic index estimates. Acad Radiol 1997; 4: 587–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]