Abstract

Background

Lacunar infarcts are a frequent type of stroke caused mainly by cerebral small-vessel disease. The effectiveness of antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention has not been defined.

Methods

We conducted a double-blind, multicenter trial involving 3020 patients with recent symptomatic lacunar infarcts identified by magnetic resonance imaging. Patients were randomly assigned to receive 75 mg of clopidogrel or placebo daily; patients in both groups received 325 mg of aspirin daily. The primary outcome was any recurrent stroke, including ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage.

Results

The participants had a mean age of 63 years, and 63% were men. After a mean follow-up of 3.4 years, the risk of recurrent stroke was not significantly reduced with aspirin and clopidogrel (dual antiplatelet therapy) (125 strokes; rate, 2.5% per year) as compared with aspirin alone (138 strokes, 2.7% per year) (hazard ratio, 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72 to 1.16), nor was the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke (hazard ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.09) or disabling or fatal stroke (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.64). The risk of major hemorrhage was almost doubled with dual antiplatelet therapy (105 hemorrhages, 2.1% per year) as compared with aspirin alone (56, 1.1% per year) (hazard ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.71; P<0.001). Among classifiable recurrent ischemic strokes, 71% (133 of 187) were lacunar strokes. All-cause mortality was increased among patients assigned to receive dual antiplatelet therapy (77 deaths in the group receiving aspirin alone vs. 113 in the group receiving dual antiplatelet therapy) (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.04; P = 0.004); this difference was not accounted for by fatal hemorrhages (9 in the group receiving dual antiplatelet therapy vs. 4 in the group receiving aspirin alone).

Conclusions

Among patients with recent lacunar strokes, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent stroke and did significantly increase the risk of bleeding and death. (Funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and others; SPS3 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00059306.)

Small subcortical brain infarcts, commonly known as lacunar strokes, constitute about 25% of ischemic strokes1–3 and are particularly frequent among Hispanics.4–9 Although lacunar strokes occasionally result from mechanisms of brain ischemia such as cardiogenic embolism or carotid-artery stenosis, most result from intrinsic disease of the small penetrating arteries. This underlying disorder is the most frequent cause of covert brain infarcts and vascular cognitive impairment.10–12 To our knowledge, the secondary prevention of lacunar stroke as detected by the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has not been the focus of a randomized trial.

Aspirin is accepted as standard antiplatelet therapy in patients with lacunar infarcts.13 The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation14 and those with acute coronary syndromes,15 but dual antiplatelet therapy has been associated with increased bleeding.16

The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial tested two randomized interventions, in a 2-by-2 factorial design, in patients with recent symptomatic, MRI-confirmed lacunar stroke: clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone and two target levels of systolic blood pressure. The antiplatelet component of the trial was terminated at the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee because of lack of efficacy combined with evidence of harm. The final results of the antiplatelet component of the trial are presented here.

Methods

Study Design

In brief, SPS3 was a randomized, multicenter clinical trial conducted in 82 clinical centers in North America, Latin America, and Spain. (Details of the rationale for the study, the design, and characteristics of the participants have been described elsewhere.17,18) In accordance with the 2-by-2 factorial design of the study, eligible patients underwent simultaneous randomization to the antiplatelet intervention (in which both patients and practitioners were unaware of group assignments) and to one of the two groups defined by target levels for systolic blood pressure (<130 mm Hg vs. 130 to 149 mm Hg) (with patients and practitioners aware of the group assignments). Randomized assignments, stratified according to clinical center and baseline hypertensive status, were generated with the use of a permuted-block design (with a variable block size) and protected from previewing. All participants were given 325 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily and were randomly assigned to receive 75 mg of clopidogrel daily or a matching placebo, with adherence measured by means of pill counts performed at quarterly follow-up visits.

The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the protocol and statistical analysis plan, which are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The trial was designed and executed by the SPS3 investigators. The members of the writing group vouch for the data and wrote this report without professional editorial assistance. Participation required written informed consent and approval by the human research subjects committee at each study center.

SPS3 was an investigator-initiated trial funded by a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Clopidogrel and the matching placebo were donated by Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb, but neither company had any involvement in the design or execution of the trial or in the analysis or reporting of the data. There were no confidentiality agreements between the study sponsor (NINDS) and investigators.

Selection of Patients

Patients were eligible for participation in the study if they were 30 years of age or older, had undergone a symptomatic lacunar stroke within the preceding 180 days, and did not have surgically amenable ipsilateral carotid artery disease or major risk factors for cardioembolic sources of stroke. To avoid a lowering of blood pressure after acute stroke, randomization did not take place for at least 2 weeks after the qualifying stroke. Participants with a clinical lacunar syndrome were required to meet MRI criteria that included a lesion measuring 2.0 cm or less in diameter on diffusion-weighted imaging that corresponded to a positive apparent-diffusion-coefficient image or a lesion with a well-delineated area of focal hyperintensity that was 2.0 cm or less in diameter on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging or T2-weighted imaging that corresponded to the clinical syndrome. Patients with transient lacunar ischemic attacks were included only if there was evidence of the attacks on diffusion-weighted MRI. MRI scans were assessed by the investigators at each study site and then submitted for interpretation by a neuroradiologist located at the SPS3 Coordinating Center. Patients with MRI evidence of a recent or remote cortical infarct, a large subcortical infarct (measuring more than 1.5 cm in diameter), or a history of intracerebral hemorrhage were excluded (but those with microbleeding were not).17 Additional exclusion criteria were disabling stroke (defined by a modified Rankin score of 4 or more on a scale of 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more severe disability) and previous intracranial hemorrhage (with the exception of traumatic hemorrhage) or cortical ischemic stroke.

Outcomes

The primary hypothesis was that clopidogrel added to aspirin would be superior to aspirin alone in reducing the primary outcome of stroke recurrence (any ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage, including subdural hematomas). Prespecified subgroup analyses assessed the primary outcome according to ethnic group (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic white), use of aspirin at the time of the qualifying event (yes vs. no), and status with respect to diabetes. Ethnic group was self-reported; participants who identified themselves as Spanish or Latino were classified as Hispanic according to the criteria used in the San Antonio Heart Study.19

Patients taking aspirin (at any dose) at the time of their qualifying event were included in the subgroup analyses; patients taking aspirin in combination with clopidogrel (45 patients), clopidogrel alone (35 patients), or other antiplatelet agents, alone or in combination (34 patients), were not included in these analyses. Additional subgroup analyses, which were not prespecified, were based on age, sex, and region; the results of these analyses are reported here.

Ischemic stroke was clinically defined as a focal neurologic deficit of sudden onset persisting for more than 24 hours, and without evidence of hemorrhage on neuroimaging. Intracranial hemorrhages included those in intracerebral, subdural, epidural, and subarachnoid locations as documented on neuroimaging. Assessment for recurrent stroke took place 3 to 6 months after the initial stroke. Recurrent stroke was considered to be disabling if the modified Rankin score was 4 or higher. In the 25% of participants for whom a Rankin score obtained within the 3-to-6-month interval after the initial stroke was not available, the last available Rankin score after stroke recurrence was used. Strokes were counted as fatal if death occurred within 30 days or if it occurred after 30 days and was attributable to the stroke.

Secondary outcomes included acute myocardial infarction and death, classified as having a vascular, nonvascular, or unknown cause. The primary safety outcome was major extracranial hemorrhage, defined as serious or life-threatening bleeding requiring transfusion of red cells or surgery or resulting in permanent functional sequelae or death. All reported efficacy and safety outcomes were confirmed by a central adjudication committee that was unaware of the treatment assignments and that classified ischemic strokes according to the presumed mechanism on the basis of available diagnostic studies.

Statistical Analysis

The initial sample size of 2500 patients was calculated on the basis of an assumed average follow-up of 3 years, an estimated 3-year rate of recurrent stroke of 21%, and a 25% relative reduction in the risk of stroke in the group receiving dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel and aspirin), with a type I error of 0.05 and a type II error of 0.10. The sample size was reestimated midway through the trial to assess power on the basis of the observed overall event rate at that time, with the result that the sample size was increased from 2500 to 3000 patients, with a 1-year extension of follow-up.20

The main analyses were based on standard time-to-event methods, with each treatment group assessed with the use of the log-rank test; Cox proportional-hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios. The time to an event was calculated as the time to the first event in the case of multiple events of the same type and for the composite end point of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from vascular causes. Data for patients without events were censored at the time of termination of study participation or at death. The interaction between the antiplatelet therapy and blood-pressure therapy was assessed to ensure that it was not significant before the effect of the antiplatelet therapy was assessed. For each model, we assessed the interaction between study treatment and study time, which was defined as a continuous variable to test whether the proportional-hazards assumption was violated. Interactions between planned covariates and antiplatelet assignment were evaluated with the use of Cox models to determine whether the treatment effect differed in specific subgroups. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle.

The trial was monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring committee selected by the study sponsor. Two planned interim analyses were performed after one third and two thirds of the primary events had transpired, with the use of Haybittle–Peto bounds and with futility analyses based on conditional power. At the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee, the antiplatelet component of the trial was stopped by the sponsor 10 months before the planned end date, after completion of the second planned interim analysis, because of futility with respect to the primary outcome coupled with evidence of harm. The component of the trial involving blood-pressure targets is ongoing, and no significant interactions between the two interventions have been found with regard to the primary outcome.

Results

Study Participants

Between 2003 and 2011, a total of 3020 patients were enrolled in the study: 1503 in the group treated with aspirin plus placebo and 1517 in the group treated with aspirin plus clopidogrel. A total of 1960 of the participants (65%) were from North America, 694 (23%) from Latin America, and 366 (12%) from Spain. Participants had been followed for a mean of 3.4 years (range, 0 to 8.2) at the time of termination of the antiplatelet component of the study in August 2011 (see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 63±11 years, and 63% were men; 75% of the participants had a history of hypertension, 37% had diabetes, and 20% were current tobacco smokers (Table 1). The median time from the date of the qualifying stroke to randomization was 62 days. Among all participants, the mean systolic blood pressure was 143±19 mm Hg at study entry and declined to 131±16 mm Hg by the time of the last follow-up visit.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants.*

| Characteristic | Aspirin plus Placebo (N = 1503) |

Aspirin plus Clopidogrel (N = 1517) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 63 | 63 |

| Male sex (%) | 64 | 62 |

| Race or ethnic group (%)† | ||

| White | 52 | 52 |

| Hispanic | 31 | 31 |

| Black | 17 | 17 |

| Region or country (%) | ||

| North America | 65 | 65 |

| Latin America | 23 | 23 |

| Spain | 12 | 12 |

| History of hypertension (%) | 74 | 76 |

| Mean blood pressure at screening visit (mm Hg) | 143/78 | 143/78 |

| Diabetes (%) | 38 | 35 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) | 11 | 10 |

| Previous clinical stroke or transient ischemic attack (%) | 15 | 15 |

| Current tobacco smoker (%) | 21 | 20 |

| Qualifying event (%) | ||

| Ischemic stroke (%) | 97 | 97 |

| Transient ischemic attack (%) | 3 | 3 |

| Type of lacunar syndrome (%) | ||

| Pure motor hemiparesis | 35 | 31 |

| Pure sensory stroke | 10 | 10 |

| Sensorimotor stroke | 30 | 32 |

| Other | 25 | 27 |

| Use of aspirin at time of qualifying event (%) | 28 | 28 |

| Use of statin at any follow-up visit (%) | 85 | 84 |

There were no significant differences between the treatment groups for any variable. Additional baseline characteristics have been reported elsewhere.18

Data on race or ethnic group are self-reported. Participants who reported that they were Spanish or Latino were classified as Hispanic according to the criteria used in the San Antonio Heart Study.19

During active participation, the estimated average rate of adherence to the assigned antiplatelet regimen was 94%. Permanent discontinuation of assigned antiplatelet therapy occurred in 30% of the patients in the group receiving dual antiplatelet therapy and in 27% of the patients receiving aspirin alone (P = 0.02). Among participants who did not complete the study, 2% were lost to follow-up, 7% withdrew consent, 5% left because of site closure, 1% withdrew at the physician’s request, and 1% withdrew for other reasons (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Statin therapy was prescribed for 84% of patients during follow-up.

Recurrent Stroke

A total of 263 participants had a recurrent stroke: 224 (85%) had an ischemic stroke and 34 (13%) had an intracranial hemorrhage; the type of stroke was unknown for the remaining 5 patients (2%) because they did not undergo neuroimaging. There was no significant interaction between the antiplatelet and blood-pressure therapies (P = 0.46 for the interaction); the hazard ratio for recurrent stroke in the group with a blood-pressure target of 130 to 149 mm Hg was 0.84 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61 to 1.17) and the hazard ratio in the group with a target of less than 130 mm Hg was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.71 to 1.45).

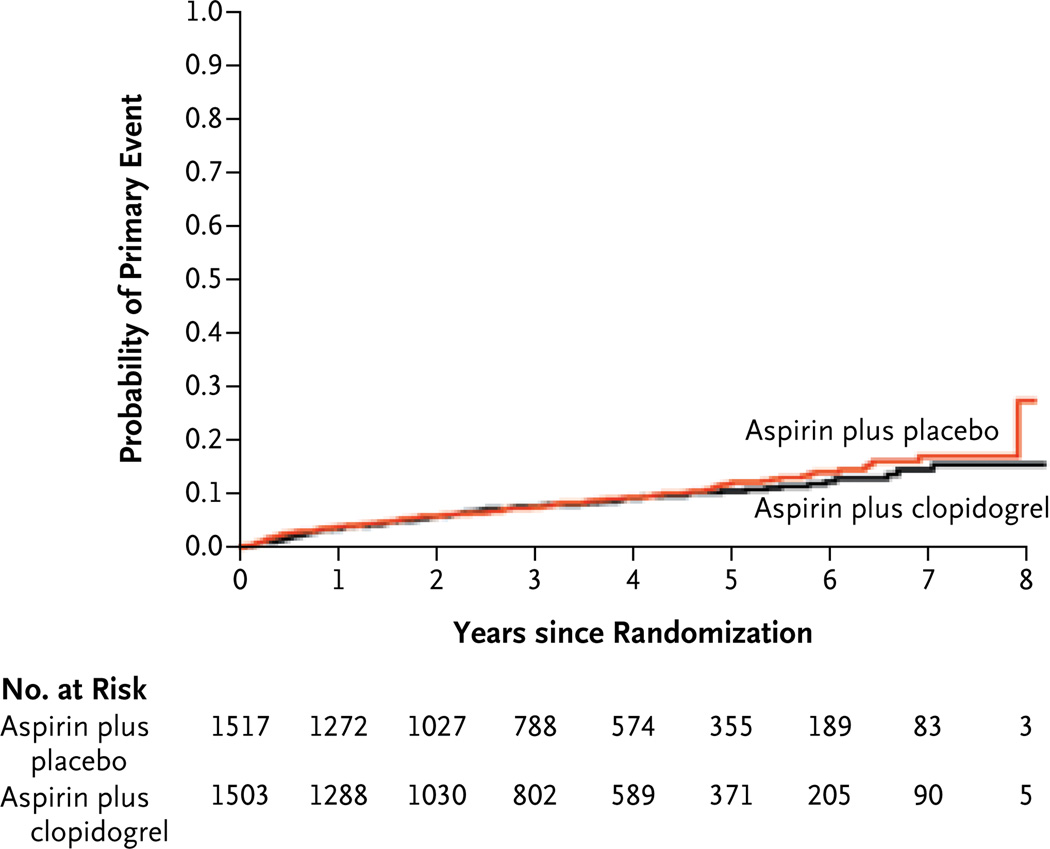

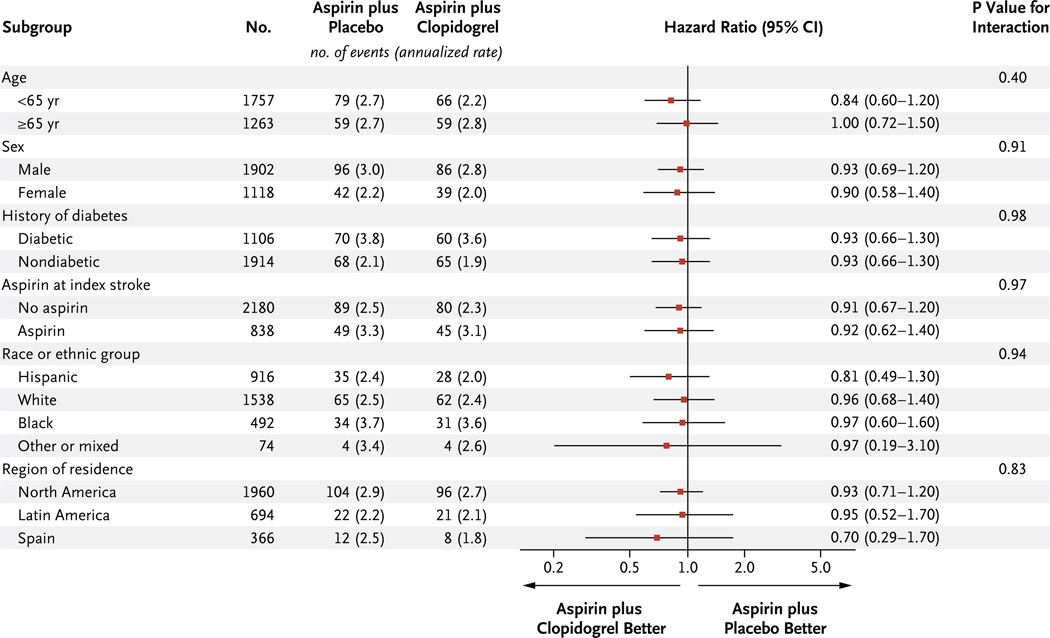

The risk of recurrent stroke among patients assigned to receive aspirin alone was 2.7% per year and was not significantly reduced among those receiving dual antiplatelet therapy (2.5% per year; hazard ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.16) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). A nonsignificant decrease of 18% in the relative risk of recurrent ischemic stroke associated with dual antiplatelet therapy was observed and was offset by a nonsignificant increase of 70% in the relative risk of intracerebreal hemorrhage (Table 2, and fig. S2B in the Supplementary Appendix) There was no heterogeneity of treatment effect on the primary outcome according to age or sex or among the prespecified subgroups (Fig. 2). In the group receiving dual antiplatelet therapy, there was no significant reduction in the risk of disabling or fatal stroke (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.64) or in the composite outcome of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from vascular causes (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.11) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary Efficacy Outcomes.*

| Outcome | Aspirin plus Placebo (N = 1503) |

Aspirin plus Clopidogrel (N = 1517) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | rate (%/yr) | no. | rate (%/yr) | |||

| All strokes (ischemic and hemorrhagic) | 138 | 2.7 | 125 | 2.5 | 0.92 (0.72–1.16) | 0.48 |

| Ischemic stroke | 124 | 2.4 | 100 | 2.0 | 0.82 (0.63–1.09) | 0.13 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 13 | 0.25 | 21 | 0.42 | 1.65 (0.83–3.31) | 0.15 |

| Unknown† | 1 | 0.02 | 4 | 0.08 | 3.97 (0.44–35.47) | 0.22 |

| Disabling or fatal stroke‡ | 40 | 0.78 | 42 | 0.84 | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) | 0.79 |

| Transient ischemic attack without stroke | 39 | 0.78 | 28 | 0.57 | 0.73 (0.45–1.18) | 0.19 |

| Myocardial infarction | 38 | 0.71 | 31 | 0.59 | 0.84 (0.52–1.35) | 0.47 |

| Other thromboembolic events§ | 12 | 0.22 | 21 | 0.40 | 1.81 (0.89–3.68) | 0.10 |

| Major vascular event¶ | 174 | 3.4 | 153 | 3.1 | 0.89 (0.72–1.11) | 0.29 |

| All deaths | 77 | 1.4 | 113 | 2.1 | 1.52 (1.14–2.04) | 0.004 |

| Vascular causes | 19 | 0.35 | 27 | 0.51 | 1.46 (0.81–2.64 | 0.20 |

| Cerebral | 9 | 0.17 | 10 | 0.19 | 1.13 (0.46–2.78) | 0.79 |

| Noncerebral | 10 | 0.18 | 17 | 0.32 | 1.77 (0.81–3.87) | 0.15 |

| Probable vascular causes | 6 | 0.11 | 18 | 0.34 | 3.09 (1.23–7.80) | 0.02 |

| Nonvascular causes | 31 | 0.57 | 39 | 0.73 | 1.31 (0.82–2.10) | 0.26 |

| Uncertain | 21 | 0.39 | 29 | 0.55 | 1.41 (0.82–2.52) | 0.21 |

A time-to-first-event model was used for each outcome category; rates are annualized. The total number of patient-years of exposure for the primary outcome (all strokes) was 5026 for patients assigned to aspirin plus placebo and 5114 for those assigned to aspirin plus clopidogrel. CI denotes confidence interval.

The five patients with strokes classified as unknown were those who did not undergo neuroimaging; three of the stroke events were defined as probable ischemic events on central adjudication, and two were defined as probable ischemic events on local adjudication.

Of 82 strokes that were classified as disabling or fatal (including ischemic, hemorrhagic, and unknown), 16 were fatal strokes and 65 were defined as disabling on the basis of a modified Rankin score of 4 or more (on a scale of 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more severe disability). Another 14 strokes could not be classified and were excluded from these analyses. Data for patients with nondisabling strokes were censored at the time of the primary event.

Other thromboembolic events included venous thromboembolism (18 events with dual antiplatelet therapy and 10 with aspirin alone) and peripheral arterial embolism (2 and 1, respectively).

Major vascular events were defined as stroke, myocardial infarction, or death resulting from a vascular event.

Figure 1. Probability of the Primary Outcome.

The hazard ratio for the primary outcome, recurrent stroke, was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.2).

Figure 2. Hazard Ratios for the Primary Outcome in Subgroups of Participants.

Deaths

All-cause mortality was increased among patients assigned to dual antiplatelet therapy as compared with those assigned to aspirin alone (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.14 to 2.04; P = 0.004), with similar trends toward an increase in death with dual antiplatelet therapy observed for all categories of cause of death (Table 2, and Fig. S2C in the Supplementary Appendix). Fatal stroke occurred in 16 patients, with death occurring in 13 of these patients within 30 days of the stroke. Fatal hemorrhages occurred in 9 patients assigned to dual antiplatelet therapy and 4 assigned to aspirin alone (hazard ratio, 2.29; P = 0.17); 85% of fatal hemorrhages (11 of 13) were intracranial (Table 3).

Table 3.

Safety Outcomes.*

| Outcome | Aspirin plus Placebo (N = 1503) |

Aspirin plus Clopidogrel (N = 1517) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | rate (%/yr) | no. | rate (%/yr) | |||

| All major hemorrhages | 56 | 1.1 | 105 | 2.1 | 1.97 (1.41–2.71) | <0.001 |

| Intracranial hemorrhages† | 15* | 0.28 | 22 | 0.42 | 1.52 (0.79–2.93) | 0.21 |

| Intracerebral | 8 | 0.15 | 15 | 0.28 | 1.92 (0.82–4.54) | 0.14 |

| Subdural or epidural | 6 | 0.11 | 7 | 0.13 | 1.23 (0.41–3.64) | 0.72 |

| Other | 4 | 0.07 | 2 | 0.04 | 0.53 (0.10–2.89) | 0.46 |

| Extracranial bleeding | 42 | 0.79 | 87 | 1.7 | 2.15 (1.49–3.11) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal‡ | 28 | 0.52 | 58 | 1.1 | 2.14 (1.36–3.36) | <0.001 |

| Fatal hemorrhages | 4 | 0.07 | 9 | 0.17 | 2.29 (0.70–7.42) | 0.17 |

| Intracranial | 4 | 0.07 | 7 | 0.13 | 1.78 (0.52–6.07) | 0.36 |

| Extracranial | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.04 | — | — |

A time-to-first-event model was used for each outcome category; rates are annualized. All adjudications were performed centrally by the SPS3 adjudication committee. CI denotes confidence interval.

In the group taking aspirin plus placebo, two events were adjudicated as both intracerebral and other, and one event was adjudicated as both intracerebral and subdural. In the group taking aspirin plus clopidogrel, one event was adjudicated as both intracerebral and other, and one event was adjudicated as both intracerebral and subdural.

The site of bleeding was determined by an investigator at the local study center.

Hemorrhage

The rate of all major hemorrhages was 1.1% per year among patients receiving aspirin alone and was almost doubled among those assigned to dual antiplatelet therapy (hazard ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.71; P<0.001) (Table 3, and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix) Although the increase in central nervous system bleeding in the dual antiplatelet therapy group was not significant (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.79 to 2.93), the yearly rate of major extracranial hemorrhage was more than doubled in that group (hazard ratio, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.49 to 3.11; P<0.001) (Table 3).

Ischemic Stroke

Among the patients with recurrent acute ischemic strokes who underwent neuroimaging, 58% (126 of 219) had evidence of an acute small sub-cortical infarct on neuroimaging, and 71% of classifiable recurrent ischemic strokes (133 of 187) were deemed to be recurrent lacunar strokes on the basis of both clinical assessment and imaging review. The rate of recurrent lacunar infarcts was not reduced among patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy (infarcts occurred in 67 of the patients receiving aspirin alone and 66 of the patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy) (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Discussion

In this cohort of patients with recent lacunar stroke identified on MRI, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin did not reduce stroke recurrence. The extreme of the 95% confidence interval around the observed point estimate was bounded by a relative risk reduction of 28% with dual antiplatelet therapy, arguably excluding a clinically meaningful reduction, considering the increased bleeding associated with dual antiplatelet therapy. After the SPS3 trial had been designed and initiated, two large, randomized trials involving patients with a heterogeneous spectrum of vascular disease or vascular risk factors assessed dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin for the prevention of vascular events, including stroke, as compared with either aspirin alone or clopidogrel alone, and the overall results were negative.21,22 However, the importance of assessing the effect of antiplatelet agents on well-defined subtypes of ischemic stroke is illustrated by the strongly positive reduction in the risk of stroke observed in a study comparing clopidogrel plus aspirin with aspirin alone in patients with atrial fibrillation in whom the primary mechanism of stroke was cardioembolic.14 The SPS3 trial documents the lack of benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in a specific, well-defined subtype of ischemic stroke that results primarily from cerebral small-artery disease.

These results must be interpreted in the context of the other component of the trial, which involved vigorous management of blood pressure.17 The rate of recurrent stroke among patients taking aspirin alone (2.7% per year) was substantially lower than anticipated. The use of statins by the majority of the study participants and the good blood pressure control achieved probably contributed to the low observed rate in our trial, which was similar to the rates in other recent trials testing antiplatelet therapies for the prevention of recurrent stroke.23,24

Dual antiplatelet therapy was associated with a trend toward a reduction in recurrent strokes attributed to atherosclerosis but not recurrent lacunar strokes, a finding that supports the hypothesis that the role of platelets is different in different types of ischemic cerebrovascular disease (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). It has been speculated that thrombosis may have a minimal role in precipitating occlusions of small, penetrating cerebral arteries.25

The risk of major hemorrhage was increased among patients assigned to dual antiplatelet therapy rather than aspirin (hazard ratio, 1.97; P<0.001), and this increase was observed in cases of both extracranial bleeding (hazard ratio, 2.15; P<0.001) and intracranial bleeding (hazard ratio, 1.52; P = 0.21), although the latter increase was not significant. An absolute increase in the rate of major extracranial bleeding from about 1% per year with aspirin to 1.5 to 1.7% per year with dual antiplatelet therapy was anticipated on the basis of data from previous studies.14,16,26,27 In the SPS3 trial, as in previous trials,14,15 the majority of cases of excess bleeding with dual antiplatelet therapy were gastrointestinal. In the large CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance) trial, the risk of intracranial bleeding was not increased when clopidogrel was added to aspirin,22 but this result is at odds with the findings in other randomized trials.14,28

The dose of enteric-coated aspirin (325 mg daily) in the SPS3 trial was higher than that used in several other trials testing the effects of clopidogrel combined with aspirin.14,22 Exploratory analyses in one study suggested that when combined with clopidogrel, higher doses of aspirin could be less efficacious than lower doses for the prevention of vascular events.29 However, in two trials of aspirin plus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes, the aspirin dose had no observed effect on the prevention of ischemic events,30,31 nor did it have an effect on stroke outcomes in a trial involving patients with vascular disease or vascular risk factors,29 making it unlikely that the aspirin dose tested in the SPS3 trial accounted for the absence of an increase in efficacy with dual antiplatelet therapy.

The increase in the rate of death from any cause among the patients assigned to clopidogrel plus aspirin was unexpected, and the observed increase was not accounted for by fatal hemorrhages, the most biologically plausible explanation. Previous randomized trials assessing the effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin have not shown an overall increase in mortality.15,32 Consequently, the increased mortality associated with dual antiplatelet therapy observed in the SPS3 trial can probably be explained by the specific patient population or by chance. The SPS3 trial cohort had a low frequency of recognized coronary artery disease at entry (10%), a low incidence of myocardial infarction (0.7% per year), and a lower observed mortality than that in other recent stroke-prevention trials,21,23,24 suggesting that vascular disease associated with lacunar stroke has a unique profile.

In conclusion, in this clinical trial of clopidogrel and aspirin, as compared with aspirin alone, in patients with a recent lacunar stroke identified on MRI, we found that the anticipated increase in the risk of major hemorrhage with dual antiplatelet therapy was not offset by a reduction in the risk of stroke recurrence, and there was an unexpected increase in mortality. Additional results from the component of the SPS3 trial involving blood pressure control are anticipated in 2012.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01 NS38529-04A1) and by Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb, which donated the clopidogrel and matching placebo used in the study.

Footnotes

The members of the writing group (Oscar R. Benavente, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada; Robert G. Hart, Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, ON, Canada; Leslie A. McClure and Jeffrey M. Szychowski, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham; Christopher S. Coffey, University of Iowa, Iowa City; and Lesly A. Pearce, Minot, ND) of the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial assume responsibility for the overall content and integrity of the article. Address reprint requests to Dr. Benavente at the Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Brain Research Center, University of British Columbia, S169-2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 2B5, Canada, or at oscar.benavente@ubc.ca.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G, Regli F. The Lausanne Stroke Registry: analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Stroke. 1988;19:1083–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.9.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Weber M, Gefeller O, Neundoerfer B, Heuschmann PU. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke subtypes according to TOAST criteria: incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study. Stroke. 2001;32:2735–2740. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe CD, Rudd AG, Howard R, et al. Incidence and case fatality rates of stroke subtypes in a multiethnic population: the South London Stroke Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:211–216. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Brutto OH, Mosquera A, Sánchez X, Santos J, Noboa CA. Stroke subtypes among Hispanics living in Guayaquil, Ecuador: results from the Luis Vernaza Hospital Stroke Registry. Stroke. 1993;24:1833–1836. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavados PM, Sacks C, Prina L, et al. Incidence, 30-day case-fatality rate, and prognosis of stroke in Iquique, Chile: a 2-year community-based prospective study (PISCIS project) Lancet. 2005;365:2206–2215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnic differences in stroke risk factors among hospitalized patients with cerebral infarction: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 1995;45:659–663. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saposnik G, Del Brutto OH. Stroke in South America: a systematic review of incidence, prevalence, and stroke subtypes. Stroke. 2003;34:2103–2107. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000088063.74250.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worley KL, Lalonde DR, Kerr DR, Benavente O, Hart RG. Survey of the causes of stroke among Mexican Americans in South Texas. Tex Med. 1998;94:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweifler RM, Lyden PD, Taft B, Kelly N, Rothrock JF. Impact of race and ethnicity on ischemic stroke: the University of California at San Diego Stroke Data Bank. Stroke. 1995;26:245–248. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boiten J, Lodder J. Prognosis for survival, handicap and recurrence of stroke in lacunar and superficial infarction. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1993;3:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross GW, Petrovitch H, White LR, et al. Characterization of risk factors for vascular dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurology. 1999;53:337–343. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tatemichi TK, Desmond D, Paik M, et al. Clinical determinants of dementia related to stroke. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:568–575. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The ACTIVE Investigators. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [Errata, N Engl J Med 2001;345:1506, 1716.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usman MHU, Notaro LA, Nagarakanti R, et al. Combination antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention: enhanced efficacy or double trouble? Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benavente OR, White C, Pearce LA, et al. The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) study. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:164–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White CL, Szychowski JM, Roldan A, et al. Clinical features and racial/ethnic differences among 3020 participants in the Secondary Prevention of Small Sub-cortical Strokes (SPS3) trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012 Apr 17; doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.002. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazuda HP, Comeaux PJ, Stern MP, Haffner SM, Eifler CW, Rosenthal M. A comparison of three indicators for identifying Mexican Americans in epidemiologic research: methodological findings from the San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:96–112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClure LA, Szychowski J, Benavente O, Coffey CS. Sample size re-estimation in an on-going NIH-sponsored clinical trial: the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Stroke trial experience. Con-temp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1088–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diener H-C, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331–337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke E, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacco RL, Diener H-C, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bousser M-G, Amarenco P, Chamorro A, et al. Terutoban versus aspirin in patients with cerebral ischaemic events (PERFORM): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2013–2022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60600-4. [Erratum, Lancet 2011;378:402.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardlaw JM. What causes lacunar stroke? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:617–619. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.039982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Fuster V, et al. Bleeding complications with dual anti-platelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease: results from the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Circulation. 2010;121:2575–2583. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.895342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Drug-drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ. 2007;177:347–351. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart RG, Tonarelli SB, Pearce LA. Avoiding central nervous system bleeding during antithrombotic therapy: recent data and ideas. Stroke. 2005;36:1588–1593. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170642.39876.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM, et al. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:379–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:930–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909475. [Erratum, N Engl J Med 2010;363:1585.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters RJ, Mehta SR, Fox KA, et al. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Study. Circulation. 2003;108:1682–1687. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091201.39590.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palacio S, Hart RG, Pearce LA, Benavente OR. Effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on mortality: systematic review of randomized trials. Stroke. 2012;43:2157–2162. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.656173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.