Abstract

During metanephric kidney development, renin expression in the renal vasculature begins in larger vessels, shifting to smaller vessels and finally remaining restricted to the terminal portions of afferent arterioles at the entrance into the glomerular capillary network. The mechanisms determining the successive expression of renin along the vascular axis of the kidney are not well understood. Since the cAMP signaling cascade plays a central role in the regulation of both renin secretion and synthesis in the adult kidney, it seemed feasible that this pathway might also be critical for renin expression during kidney development. In the present study we determined the spatiotemporal development of renin expression and the development of the preglomerular arterial tree in mouse kidneys with renin cell-specific deletion of Gsα, a core element for receptor activation of adenylyl cyclases. We found that in the absence of the Gsα protein, renin expression was largely absent in the kidneys at any developmental stage, accompanied by alterations in the development of the preglomerular arterial tree. These data indicate that the maintenance of renin expression following a specific spatiotemporal pattern along the preglomerular vasculature critically depends on the availability of Gsα. We infer from our data that the cAMP signaling pathway is not only critical for the regulation of renin synthesis and secretion in the mature kidney but that it also is critical for establishing the juxtaglomerular expression site of renin during development.

Keywords: fetal kidney, transgenic mice

in the mammalian kidney the protease renin is predominantly produced and stored in cells of the medial layer of the afferent arteriole close to the point where the vessel breaks up into the glomerular capillary network. At this site, renin-producing cells, identifiable by the presence of numerous renin storage granules, replace the typical smooth muscle cells in the medial layer and form the walls of the vessels entering the glomeruli. Cells of the efferent arterioles or the extraglomerular mesangium only rarely express renin, although this varies to some extent with the animal species (25). The typical juxtaglomerular position of renin-producing cells is the endpoint of a highly plastic expression of renin during the development of the kidney. The developmental changes of intrarenal renin expression occur along the same pattern in all mammals, including man (3, 8–9, 12–14, 19, 23–24, 28, 34), but they have been studied in greatest detail in mouse (24) and rat kidneys (13). In the embryonic kidney, renin expression is first present in the undifferentiated metanephric mesenchyme of the kidney before vascularization of the kidney has occurred (38). Later, during fetal renal development, renin expression is also found in the developing renal artery and in interlobar and arcuate arteries. Subsequently, renin expression is observed in the developing interlobular arteries, whereas it is silenced in the bigger vessels. Around the time of birth, renin expression in mice and rats has condensed to newly developed afferent arterioles and has disappeared from interlobular arteries. With ongoing postnatal maturation of the kidneys, renin expression becomes more and more restricted to the terminal part of the afferent arterioles, i.e., to the juxtaglomerular position.

The mechanisms responsible for the successive activation and silencing of renin expression in the various segments of the developing intrarenal arterial vasculature are largely unknown. Likewise, the causes for the striking juxtaglomerular position of renin expression in the adult kidney have remained hypothetical (10, 35). The functional relevance of this characteristic shift of renin expression in the developing mammalian kidney also is not entirely clear. It has been hypothesized that renin expression may be critical for the development of afferent arterioles, since renin expression has been observed to localize to arteriolar branch points, where it precedes the budding of new arterioles (36).

A suitable approach to possibly obtain hints for the mechanisms involved in the characteristic switch-on of renin expression in the different segments of the intrarenal arteriolar tree is to consider the molecular mechanisms regulating renin gene transcription. The present knowledge about this process suggests two candidate factors for the developmental expression of renin. One is the Hox transcription factor, which is generally known to be relevant for development. The renin gene promoter contains a Hox-binding consensus motif, the deletion of which strongly reduces basal renin promoter activity, at least in vitro (31–33). A second transcription factor of major physiological impact is the cAMP response element (CRE) binding factor (CREB), for which several binding sites in the human and mouse renin promoter have been identified. Deletion of CRE sites also has been shown to lower renin promoter activity and to attenuate or blunt its stimulation (1, 11, 22, 30, 32, 41, 44, 45). Strong supportive evidence that the CREB/cAMP signaling pathway plays an important role for basal and regulated renin expression in the adult kidney comes from experiments in which Gsα, the crucial G protein mediating receptor-induced activation of adenylyl cyclase, was selectively deleted in renin-producing cells (4). In these mice, basal renin expression was very low, and it responded only minimally to stimuli that typically activate physiological control mechanisms of renal renin expression and secretion (4). In view of this apparently crucial role of the cAMP pathway for the expression of renin and its regulation in the mature kidney, it is conceivable that this signaling cascade also may play an important role in the development of renin expression in the kidney. In the present study we have therefore characterized the spatiotemporal expression of renin in mouse kidneys developing in the absence of Gsα in renin-producing cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Experimental animals were derived from crosses of mice with targeted insertion of Cre recombinase into the Ren1d locus (Ren1d+/Cre, genetic background 129J/C57Bl/6 ) (39) and mice in which exon 1 of the Gnas gene was flanked by loxP sites (E1fl/fl, genetic background 129J/Black Swiss mix) (5). All mice used in this study were offspring of compound heterozygotes (Ren1d+/Cre/GnasE1+/fl). Studies were performed in wild-type (Ren1d+/+/GnasE1+/+) and renin cell-specific Gsα knockout mice (Ren1d+/Cre/GnasE1fl/fl). In our experiments we investigated in both genotypes in four adult kidneys and in three to five animals of the fetal or postpartal stages. Genotyping was done as previously described (4). Animal care and experimentation were approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Animal Care und Use Committee and carried out in accordance with National Institutes of Health principles and guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Immunohistochemistry for renin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA).

Kidneys were sampled from fetuses at embryonic days 16 and 18 after formation of vaginal plugs (embryonic day 0), from pups at postnatal day 1, and from adult mice. After death, kidneys from fetal and newborn mice were dissected and fixed for 24 h at 4°C in methyl Carnoy's solution (60% methanol, 30% chloroform, and 10% glacial acetic acid) (37). Kidneys from adult mice were perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed kidneys were dehydrated by a graded series of alcohol solutions (2× 70, 80, 90, and 100% methanol), followed by 100% isopropanol for 0.5 h, and embedded in paraffin.

Immunolabeling was performed on 5-μm paraffin sections. After blocking with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 20 min and with 10% horse serum-1% BSA in PBS for 0.5 h at room temperature, sections were incubated with chicken anti-renin IgG (diluted 1:200; Davids Biotechnologie, Regensburg, Germany) and mouse anti-α-SMA IgG (diluted 1:100; Beckman Coulter, Immunotech, Krefeld, Germany) overnight at 4°C. After several washing steps and blocking with phenylhydrazine, the sections were incubated with Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgG and rhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG fluorescent antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) for 2 h and mounted with glycergel (DakoCytomation, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Three-dimensional reconstruction.

Digitalization of the antibody-stained serial sections was performed using an AxioCam MRm camera (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) mounted on an Axiovert200M microscope (Zeiss) with fluorescence filters for renin and α-SMA (TRITC, filter set 43; Cy2, filter set 38 HE; Zeiss). After acquisition, a stack of equal-size images was built using the graphic tool ImageJ (Wayne Rasband; NIH, Bethesda, MD). The equalized data were then imported into the Amira 4.1 visualization software (Mercury Computer Systems, Chelmsford, MA) on a Dell Precision 690 computer system (Dell) and split into the renin and α-SMA channels. After this step, the renin and α-SMA channels were aligned. In the segmentation step, the α-SMA and renin data sets served as a scaffold and were spanned manually or automatically using gray scale values. Matrixes, volume surfaces, and statistics were generated from these segments. Measurement of the length of the afferent arterioles was done using Amira 4.1 visualization software (Mercury Computer Systems). For analysis, at least 50 afferent arterioles from both genotypes at each developmental stage were compared.

Statistical analysis.

Values are means ± SE. Differences between both genotypes were analyzed by ANOVA and Bonferroni's adjustment for multiple comparisons. Probability values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Renal vascular development.

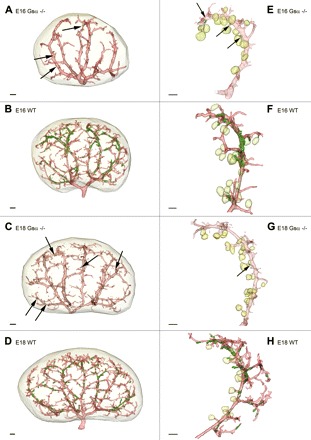

Arterial preglomerular trees from wild-type (WT) mice and from mice with renin-expressing cell-specific deletion of Gsα (RC-Gsα−/−) were reconstructed at different stages of development from serial sections stained with renin and α-SMA antibodies. Based on our previous experience, the developmental stages at which major changes of renin expression in the kidney occur were chosen (37). Figure 1 shows representative two-dimensional immunohistochemistry of kidneys at days 16 and 18 of development, 1 day after birth, and after maturation. At day 16 of embryonic development, the renal artery had divided into two interlobar arteries, which in turn branched into arcuate arteries composed of the arcuate trunks and their eponymous T-shaped arcs (Fig. 2A). At this stage, side branches had arisen from the concave side of the arcuate trunks forming the afferent arterioles of juxtamedullary glomeruli. In addition, side boughs were seen to diverge at right angles from the convex side of the arcuate trunks, and these later develop into cortical interlobular arteries (Fig. 2, A and E). At this stage of development, no divergence in the general shape of the vascular tree could be found in the kidneys of mice with renin cell-specific Gsα-deficiency (Fig. 2, B and F). We noticed, however, a paucity of branches and shortening of afferent arterioles in Gsα-deficient mice already at day 16 of development. This phenomenon persisted until adulthood (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Renin (red) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; green) immunoreactivity in kidney sections of wild-type (WT) mice and mice with renin-expressing cell (RC)-specific deletion of Gsα (Gsα−/−) at days 16 and 18 of embryonic development (E16 and E18), 1 day after birth (PP1), and after maturation (adult). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Fig. 2.

Reconstruction of α-SMA-immunoreactive vascular structures (red) and renin-immunoreactive areas (green) in developing kidneys of WT and RC Gsα−/− mice as a whole organ model (A–D) and in single developing arcuate arteries (E–H) of E16 RC Gsα−/−(A and E), E16 WT (B and F), E18 RC Gsα−/− (C and G), and E18 WT mice (D and H). The light green color indicates glomeruli. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Fig. 3.

Length of afferent arterioles in kidneys of RC Gsα−/− and WT mice at E16 and E18, at PP1, and after maturation (adult). Data are means ± SE of 50 afferent arterioles from both genotypes at each developmental stage; n.s., no significant difference. *P < 0.05.

On embryonic day 18 (Fig. 2, C and G), the formation and elongation of later interlobular arteries from arcuate trunks and T-shaped arcs had progressed, and the branching of afferent arterioles from these segments had continued. Although the global architecture of the preglomerular arterial tree in mice with renin cell-specific absence of Gsα protein was not apparently different from that of WT (Fig. 2, D and H), there was a paucity of branches and branching points.

Until 1 day after birth, the side arteries had developed further and had processed an increasing number of juxtamedullary afferent arterioles in both normal and RC-Gsα−/− mice (Fig. 4, A and D). At this stage, numerous ramifications branched off from T-shaped arches of the arcuate arteries, indicating the beginning formation of interlobular arteries (Fig. 4, A, B, D, and E), in the subcapsular zone. With further development, the growth of cortical radial interlobular arteries and their associated afferent arterioles continued until they formed the typical radially arranged and exceedingly long interlobular arteries from which the afferent arterioles branch off in the adult kidney (Fig. 4, C and F). In addition to a decrease in length of the afferent arterioles, the number of cortical afferent arterioles was somewhat reduced in adult RC-Gsα−/− kidneys, although the gross architecture of the preglomerular vessel tree was similar to that of WT kidneys (Fig. 4, C and F).

Fig. 4.

Reconstruction of α-SMA-immunoreactive vascular structures (red) and renin-immunoreactive areas (green) in developing kidneys of WT and RC Gsα−/− mice as whole organ model (A–C) and in single arcuate arteries (D–F) of PP1 RC Gsα−/− (A and D), PP1 WT (B and E), adult RC Gsα−/− (C), and adult WT mice (F). The light green color indicates glomeruli. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Development of renin expression.

Intrarenal renin expression in WT mice was first observed at the early metanephric stage, when single renin-expressing cells developed at the more distal part of the arcuate arteries. From this initial site, renin expression was found to expand along the arcuate side arteries as well as along the proximal part of the arcuate arteries (embryonic day 16) (Fig. 2, B and F). Compared with WT mice in which renin-expressing cells covered nearly the entire arcuate arteries, RC-Gsα−/− mice showed no renin expression in these vessel segments. Renin-expressing cells were occasionally found in branching afferent arterioles (Fig. 2, A and E).

On day 18 of embryonic development, renin expression had shifted from the proximal to distal parts of the preglomerular tree (Fig. 2, D and H) and showed an intermittent expression pattern. In RC-Gsα−/− mice, in contrast, renin expression was largely absent in the preglomerular vessel tree and was again only found in single side boughs of future juxtamedullary afferent arterioles (Fig. 2, C and G).

On day 1 after birth, renin had disappeared from the arcuate arteries and was mainly found in large interlobular side arteries and in afferent arterioles in a striped, discontinuous pattern (Fig. 4, B and E). Essentially no renin expression could be demonstrated in RC-Gsα−/− mice (Fig. 4, A and D). Finally, our results confirm the well-known restriction of renin expression to the terminal part of the afferent arteriole in the adult kidney (Fig. 4F). Again, kidneys of adult RC-Gsα−/− mice were largely devoid of detectable renin expression (Fig. 4C). At all developmental stages examined in this study, renin immunoreactivity was found only in association with blood vessels. Our study, however, does not rule out the possibility that extravascular renin expression in the kidney also may occur, which might have escaped our notice because of technical limitations produced by the fixation procedure or the sensitivity of the renin antibody.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that renin-expressing cell -specific deletion of the guanine nucleotide binding protein Gsα, which couples membrane receptors to stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity, was associated with a nearly complete abolition of renin in the developing mouse kidney. Thus the cAMP signaling cascade appears to be of critical importance for the initial appearance of renin in larger renal vessels during kidney development. Furthermore, it is conceivable that this pathway might be also required for its typical shift from the larger vessels to the juxtaglomerular portions of afferent arterioles. Since Gsα mediates receptor-induced activation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP formation, our findings imply that extracellular ligands coupled to Gsα are responsible for the characteristic spatiotemporal pattern of renin expression in the developing kidney. The nature of these ligands is unclear. Catecholamines exert profound effects on renin expression and renin release via activation of Gs-coupled β1-adrenergic receptors (7, 17, 20). Adult mice with an abrogation of β1/β2-adrenoreceptors have been shown to have a greatly reduced basal renin expression and reduced regulatory responsiveness (20). Since β-adrenergic receptors are expressed in fetal kidneys (26), their activation may be responsible for stimulating the cAMP/PKA cascade. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2-derived prostanoid signaling through Gs-coupled prostaglandin E (EP) or prostacyclin (IP) receptors on juxtaglomerular cells serves as an important regulatory pathway of renin expression in the adult kidney (6, 16, 21, 27, 43). However, since COX-2 is only expressed at very low levels in the fetal kidney, the role of these receptors in initiating renin expression may be less likely (18). Nevertheless, the technique used in the present study will permit a more direct evaluation of β-adrenoreceptors and COX-2 in the developmental regulation of renin expression.

Expression of Cre recombinase under control of the endogenous renin promoter was achieved by replacing one allele of Ren1d with the Cre gene. Thus the Cre-expressing animals used in this study possess only a single copy of the Ren1d gene in addition to the two copies of Ren2. Since deletion of one renin allele does not cause a change of phenotype even in mouse strains without Ren2 (38), the marked reduction of renin expression as seen in our study did not result from the loss of one Ren1d allele. On the other hand, as shown previously (4), heterozygous Ren1d-driven Cre expression is obviously capable to generate Cre activities sufficient to effectively excise floxed Gsα alleles.

The expression of renin and its spatial and temporal development were severely affected by renin cell-specific deletion of Gsα, and as a consequence, the total number of arterioles and the length of the afferent arterioles were diminished. This finding is in conformity with the notion that the distribution of renin during development is associated with branching of the renal arterioles (36). In fact, previous reports showed striking alterations in the kidney vasculature of animals with either inhibition of angiotensin actions (42) or with deletion of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) genes. Vascular alterations are accompanied by additional abnormalities, including tubular and medullary underdevelopment (40, 42). The structural abnormalities of RAS deficiency are to a large extent postnatal events, when most of the kidney vascular branching occurs, and are usually more pronounced, including arteriolar thickening, and have been described as delayed or arrested maturation (42). In the present study, RC-Gsα−/− mice still have residual renin production and renin secretion (4), which might explain why the vascular phenotype in these mice is somewhat moderate than that seen in mice with a complete interruption of the RAS.

Our data indicate that a Gsα-dependent mechanism is critical for the activation of the renin promoter in early embryonic development. Two possibilities may be considered as to how renin promoter activity could be regulated. It is conceivable that renin promoter activity is initiated through a Hox-dependent pathway independent of cAMP (31–33), which in consequence leads to a shutdown of the cAMP signaling pathway by the deletion of Gsα. In such a scenario, cAMP could still be relevant for the maintenance of renin promoter activity, but not for its initiation. A second possibility would be that Ren1d promoter activity in renin cells is not only maintained but also initiated by the cAMP cascade. If so, one has to postulate an early elevation of cAMP in potential renin-producing cells, an event that would not occur in the absence of Gsα. Our experiments do not permit a distinction between the induction and maintenance function of cAMP for renin expression in the developing kidney. The very low, but nonetheless existing, expression of renin in the absence of Gsα may suggest an initial cAMP-independent activation of renin promoter activity. It could, however, also be explained by a quantitatively incomplete disruption of the Gsα gene or by cAMP formation independently of Gsα. It is known that Gsα-independent modulation of cAMP can occur, for example, by activation of adenylate cyclase isoforms AC5 and AC6 (2), both of which are expressed in renin-producing cells (15, 29). In any case, the very low renin expression implicates the quasi-complete excision of Gsα. This in turn requires that renin expression must be initially high enough to ensure Cre activity sufficient to delete floxed Gsα alleles.

Altogether, the results of our study suggest that receptor induced cAMP signaling is critical for vessel associated renin expression during kidney development. Whether cAMP acts as the fundamental stimulator of renin gene expression or more as an enhancer remains to be defined. It also remains to clarified which endo- or paracrine factor(s) stimulate(s) cAMP-signaling in renin cells to activate or to enhance renin gene expression during kidney development.

GRANTS

The study was financially supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB 699.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance provided by Anna M'Bangui and Susanne Fink is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams DJ, Head GA, Markus MA, Lovicu FJ, van der Weyden L, Köntgen F, Arends MJ, Thiru S, Mayorov DN, Morris BJ. Renin enhancer is critical for control of renin gene expression and cardiovascular function. J Biol Chem 281: 31753–31761, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beazely MA, Watts VJ. Regulatory properties of adenylate cyclases type 5 and 6: a progress report. Eur J Pharmacol 535: 1–12, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbone GM, Sheikh AU, Rogers S, Brewer G, Rose JC. Developmental changes in renin gene expression in ovine kidney cortex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 264: R591–R596, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Kim SM, Oppermann M, Faulhaber-Walter R, Huang Y, Mizel D, Chen M, Lopez ML, Weinstein LS, Gomez RA, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Regulation of renin in mice with Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of G protein Gsα in juxtaglomerular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F27–F37, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen M, Gavrilova O, Liu J, Xie T, Deng C, Nguyen AT, Nackers LM, Lorenzo J, Shen L, Weinstein LS. Alternative Gnas gene products have opposite effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7386–7391, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng HF, Wang JL, Zhang MZ, Wang SW, McKanna JA, Harris RC. Genetic deletion of COX-2 prevents increased renin expression in response to ACE inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F449–F456, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchill PC, Churchill MC, McDonald FD. Evidence that beta 1-adrenoceptor activation mediates isoproterenol-stimulated secretion in the rat. Endocrinology 113: 687–692, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodge AH. Sites of renin production in fetal, neonatal and postnatal Syrian hamster kidneys. Anat Rec 235: 144–150, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drukker A, Donoso VS, Linshaw MA, Bailie MD. Intrarenal distribution of renin in the developing rabbit. Pediatr Res 17: 762–765, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer E, Schnermann J, Briggs JP, Kriz W, Ronco PM, Bachmann S. Ontogeny of NO synthase and renin in juxtaglomerular apparatus of rat kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 268: F1164–F1176, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germain S, Konoshita T, Fuchs S, Philippe J, Corvol P, Pinet F. Regulation of human renin gene transcription by cAMP. Clin Exp Hypertens 19: 543–550, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez RA, Lynch KR, Chevalier RL, Wilfong N, Everett A, Carey RM, Peach MJ. Renin and angiotensinogen gene expression in maturing rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 254: F582–F587, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez RA, Lynch KR, Sturgill BC, Chevalier RL, Carey RM, Peach MJ. Distribution of renin mRNA and its protein in the developing kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 257: F850–F858, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham PC, Kingdom JC, Raweily EA, Gibson AA, Lindop GB. Distribution of renin-containing cells in the developing human kidney: an immunocytochemical study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 99: 765–769, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunberger C, Obermayer B, Klar J, Kurtz A, Schweda F. The calcium paradoxon of renin release: calcium suppresses renin exocytosis by inhibition of calcium-dependent adenylate cyclases AC5 and AC6. Circ Res 99: 1197–1206, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding P, Carretero OA, Beierwaltes WH. Chronic cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition blunts low sodium-stimulated renin without changing renal haemodynamics. J Hypertens 18: 1107–1113, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmer SR, Kaissling B, Putnik Pfeifer M K, Krämer BK, Riegger GA, Kurtz A. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of renin expression in vivo. J Hypertens 15: 1471–1479, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen BL, Stubbe J, Madsen K, Nielsen FT, Skøtt O. The renin-angiotensin system in kidney development: role of COX-2 and adrenal steroids. Acta Physiol Scand 181: 549–559, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones CA, Sigmund CD, McGowan RA, Kane-Haas CM, Gross KW. Expression of murine renin genes during fetal development. Mol Endocrinol 4: 375–383, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SM, Chen L, Faulhaber-Walter R, Oppermann M, Huang Y, Mizel D, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Regulation of renin secretion and expression in mice deficient in beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptors. Hypertension 50: 103–109, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SM, Chen L, Mizel D, Huang YG, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Low plasma renin and reduced renin secretory responses to acute stimuli in conscious COX-2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F415–F422, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klar J, Sandner P, Muller MW, Kurtz A. Cyclic AMP stimulates renin gene transcription in juxtaglomerular cells. Pflügers Arch 444: 335–344, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kon Y, Alcorn D, Murakami K, Sugimura M, Ryan GB. Immunohistochemical studies of renin-containing cells in the developing sheep kidney. Anat Rec 239: 191–197, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kon Y, Hashimoto Y, Kitagawa H, Kudo N. An immunohistochemical study on the embryonic development of renin-containing cells in the mouse and pig. Anat Histol Embryol 18: 14–26, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kon Y. Comparative study of renin containing cells. Histological approaches. J Vet Med Sci 61: 1075–1086, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Chen K, Valego NK, Carey LC, Rose JC. Ontogeny and effects of thyroid hormone on beta1-adrenergic receptor mRNA expression in ovine fetal kidney cortex. J Soc Gynecol Investig 12: 563–569, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matzdorf C, Kurtz A, Hocherl K. COX-2 activity determines the level of renin expression but is dispensable for acute upregulation of renin expression in rat kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1782–F1790, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minuth M, Hackenthal E, Poulsen K, Rix E, Taugner R. Renin immunocyto-chemistry of the differentiating juxtaglomerular apparatus. Anat Embryol (Berl) 162: 173–181, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz-Capisano MC, Ortiz PA, Harding P, Garvin JL, Harding P, Beierwaltes WH. Decreased intracellular calcium stimulates renin release via calcium-inhibitable adenylyl cyclase. Hypertension 49: 162–169, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan L, Black TA, Shi Q, Jones CA, Petrovic N, Loudon J, Kane C, Sigmund CD, Gross KW. Critical roles of a cyclic AMP responsive element and an E-box in regulation of mouse renin gene expression. J Biol Chem 276: 45530–45538, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan L, Glenn ST, Jones CA, Gross KW. Activation of the rat renin promoter by HOXD10. PBX1b PREP1, Ets-1, and the intracellular domain of notch. J Biol Chem 280: 20860–20866, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan L, Gross KW. Transcriptional regulation of renin: an update. Hypertension 45: 3–8, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan L, Xie Y, Black TA, Jones CA, Pruitt SC, Gross KW. An Abd-B class HOX. PBX recognition sequence is required for expression from the mouse Ren-1c gene. J Biol Chem 276: 32489–3294, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phat VN, Camilleri JP, Bariety Galtier M J, Baviera E, Corvol P, Menard J. Immunohistochemical characterization of renin-containing cells in the human juxtaglomerular apparatus during embryonal and fetal development. Lab Invest 45: 387–390, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pupilli C, Gomez RA, Tuttle JB, Peach MJ, Carey RM. Spatial association of renin-containing cells and nerve fibers in developing rat kidney. Pediatr Nephrol 5: 690–695, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddi V, Zaglul A, Pentz ES, Gomez RA. Renin-expressing cells are associated with branching of the developing kidney vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 63–71, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauter A, Machura K, Neubauer B, Kurtz A, Wagner C. Development of renin expression in the mouse kidney. Kidney Int 73: 43–51, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sequeira Lopez ML, Pentz ES, Robert B, Abrahamson DR, Gomez RA. Embryonic origin and lineage of juxtaglomerular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F345–F356, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sequeria-Lopez ML, Pentz ES, Nomasa Smithies O T, Gomez RA. Renin cells are precursors for multiple cell types that switch to the renin phenotype when homeostasis is threatened. Dev Cell 6: 719–728, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi N, Lopez ML, Cowhig JE Jr, Taylor MA, Hatada T, Riggs E, Lee G, Gomez RA, Kim HS, Smithies O. Ren1c homozygous null mice are hypotensive and polyuric, but heterozygotes are indistinguishable from wild-type. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 125–132, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura K, Umemura S, Yamaguchi S, Iwamoto T, Kobayashi S, Fukamizu A, Murakami K, Ishii M. Mechanism of cAMP regulation of renin gene transcription by proximal promoter. J Clin Invest 94: 1959–1967, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tufro-McReddie A, Romano LM, Harris JM, Ferder L, Gomez RA. Angiotensin II regulates nephrogenesis and renal vascular development. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F110–F115, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang JL, Cheng HF, Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition decreases renin content and lowers blood pressure in a model of renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 34: 96–101, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ying L, Morris BJ, Sigmund CD. Transactivation of the human renin promoter by the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathway is mediated by both cAMP-responsive element binding protein-1 (CREB)-dependent and CREB-independent mechanisms in Calu-6 cells. J Biol Chem 272: 2412–2420, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou X, Davis DR, Sigmund CD. The human renin kidney enhancer is required to maintain base-line rennin expression but is dispensable for tissue-specific, cell-specific, and regulated expression. J Biol Chem 281: 35296–35304, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]