Abstract

Protein disulfide isomerase, ERp5 and ERp57, among perhaps other thiol isomerases, are important for the initiation of thrombus formation. Using the laser injury thrombosis model in mice to induce in vivo arterial thrombus formation, it was shown that thrombus formation is associated with PDI secretion by platelets, that inhibition of PDI blocked platelet thrombus formation and fibrin generation, and that endothelial cell activation leads to PDI secretion. Similar results using this and other thrombosis models in mice have demonstrated the importance of ERp5 and ERp57 in the initiation of thrombus formation. The integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 play a key role in this process and interact directly with PDI, ERp5 and ERp57. The mechanism by which thiol isomerases participate in thrombus generation is being evaluated using trapping mutant forms to identify substrates of thiol isomerases that participate in the network pathways linking thiol isomerases, platelet receptor activation and fibrin generation. Protein disulfide isomerase as an antithrombotic target is being explored using isoquercetin and quercetin 3-rutinoside, inhibitors of PDI identified by high throughput screening. Regulation of thiol isomerase expression, analysis of the storage and secretion of thiol isomerases and determination of the electron transfer pathway are key issues to understanding this newly discovered mechanism of regulation of the initiation of thrombus formation.

Keywords: Thrombus, platelet, platelet inhibitor, antiplatelet agent, antithrombotic

Introduction

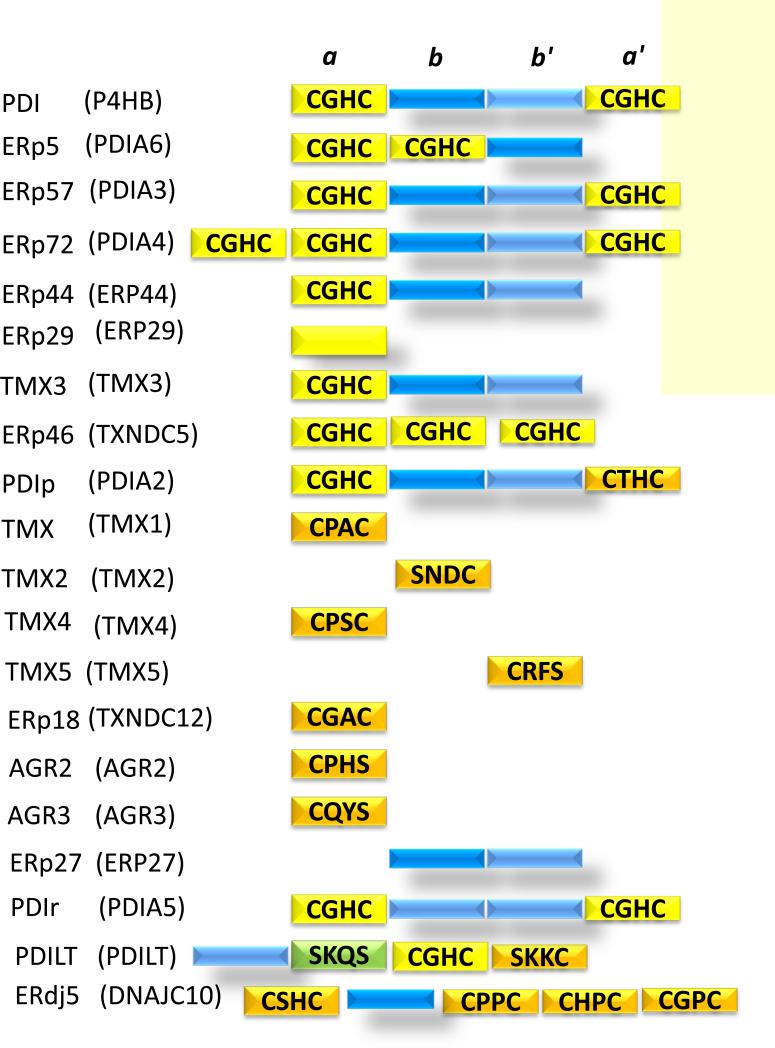

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) has long been identified as a critical functional component of the biosynthetic pathway in the synthesis of proteins. With the classic observation that denatured ribonuclease had the capacity to refold into its native structure 1, and that an enzymatic activity, the disulfide interchange enzyme, could facilitate the proper formation of the two disulfide bonds in ribonuclease, the enzyme now known as protein disulfide isomerase was identified, purified and characterized 2. Since that time, a family of thiol isomerases, now numbering twenty and significantly homologous, has been identified as part of the intracellular machinery for protein synthesis 3 (Figure 1). PDI remains the prototypic member of this family. PDI is composed of four thioredoxin-like domains: a, b, b’ and a’. The a and a’ domains contain the characteristic active site motif, CXXC, where X can be any one of a number of amino acids and C is cysteine. These domains are enzymatically active.

Figure 1. The thiol isomerase family.

Protein disulfide isomerase, the prototypic thiol isomerase, has four domains: a, b, b’, a’. Catalytically active thioredoxin-like domains containing the CGHC motif are colored yellow. Catalytically active thioredoxin-like domains with a motif other than CGHC are colored orange. Catalytically inactive thioredoxin-like domains are colored dark blue and light blue. Thiol isomerases found or secreted from platelets are highlighted with a yellow background. Modified from 3.

Although PDI, whose structure is remarkably preserved across species, contains a KDEL retention sequence to keep it in the endoplasmic reticulum bound to a KDEL receptor protein 4, PDI also resides in extracellular locations. The presence of PDI and other vascular thiol isomerases from platelets and endothelial cells and their secretion from the endothelium and platelets upon vascular injury is now well defined 5-14. How they get secreted is another matter, currently unknown.

Platelet-mediated thrombosis in vitro versus in vivo

The molecular and cellular basis of hemostasis and thrombosis has been mainly studied by the purification of components, including proteins and cells, followed by their evaluation of their action in chemically defined systems. The blood coagulation cascade has been analyzed in vitro by initiating this process with exogenous tissue factor—to turn on the extrinsic pathway-- or with kaolin or a similar substance—to activate the intrinsic pathway 15. Similarly, platelet activation has been studied in vitro by the addition of various agonists, including thrombin, collagen, epinephrine, arachnadonic acid, ADP, etc. Given the complexity of this host defense mechanism, the study of thrombus formation in a whole animal, with all of the components present, offered novel insight into this process 16. Perhaps the most unanticipated discovery was the requirement for extracellular thiol isomerases in the initiation of thrombus formation 8. It would appear that an electron transport pathway exists to convert the inactive components for thrombus formation into active components, and this requirement is only operational in in vivo systems during the initiation phase of thrombus formation. This can be seen as a regulatory system, to maintain these components temporally and spatially separate, so that pathologic thrombus formation does not occur. Thrombus formation is initiated through vascular injury—and thiol isomerases, secreted from the injured cells—are the critical initiating signals.

Vascular thiol isomerases

PDI and other thiol isomerases are secreted upon cell activation into extracellular locations outside of the ER. Platelets and endothelial cells are among the cells that secrete PDI and other thiol isomerases 5, 7, 17. PDI, ERp5, ERp57, ERp44, ERp29, ERp72 and TMX3 are stored and released from platelets 5, 6, 8, 18 (Figure 1). Similarly, PDI, ERp5, ERp57 and ERp46 are released from endothelial cells upon cell activation 9,12, 13. PDI, ERp5 and ERp57 have been implicated in the initiation of thrombus formation in vivo 8, 11-13, 19, 20. GPIbα expresses one or more free thiols on the activated platelet, but not on resting platelets 17. Similarly, alterations in the disulfide bonding structure of αIIbβ3 during platelet activation have been described 21. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that PDI may participate in the conversion of encrypted tissue factor (TF) to its active form in a favorable oxidative environment 22. However, to date, we nor others have been able to prove (or disprove) this concept experimentally, and it remains controversial 23.

Three thiol isomerases have been shown in in vivo studies to be important for thrombus formation. It is possible, even likely, that other thiol isomerases secreted during vascular injury also play a role in thrombus formation, but there is currently no experimental data to support or refute this concept. Their functional activity takes place extracellularly, following secretion from platelets and endothelium. Those thiol isomerases documented to participate in vivo in thrombus formation include PDI, ERp57 and ERp5 8, 9, 11, 19, 20.

Each of the thiol isomerases is known by multiple names, thus confusing the neophyte being introduced to this field. In this review, we will refer to the vascular thiol isomerases by their common, trivial names. However, the formal nomenclature is also indicated (Figure 1).

PDI

PDI, the prototype of these thiol isomerases, has a molecular weight of 57,000 and includes 508 amino acids. Encoded by the P4HB gene, it is composed of four thioredoxin-like domains a-b-b’-a’, where a and a’ are catalytically active units with the CGHC motif in the active site, and preceeded by a signal sequence. The C-terminal segment contains the KDEL sequence, a motif that binds to the KDEL receptor 4 and recycles the protein within the the ER as well as cell membranes, specifically peripheral membranes. Within the cell, this enzyme is primarily involved in the formation and rearrangement of disulfide bonds. The crystal structure of human PDI in both the reduced and oxidized forms shows that the four thioredoxin domains are arranged as a U, with two active sites in domains a and a’ facing each other 24. In contrast to the closed conformation of reduced PDI, oxidized PDI exists in an open state with more exposed areas and a larger cleft available for substrate binding.

ERp57

ERp57 has a molecular weight of 57,000 and includes 505 amino acids. It is encoded by the gene PDIA3. With significant structural homology to PDI, it too is composed of four thioredoxin-like domains a-b-b’-a’, where a and a’ are active thiol isomerases with the CGHC motif in the active site, and preceeded by a signal sequence. The active thioredoxin domains in ERp57 show 50% sequence similarity to parallel domains in PDI. The C-terminal segment contains the QEDL motif. Within the cell, this enzyme is primarily involved in the formation and rearrangement of disulfide bonds. ERp57 interacts with ER lectins calnexin and calreticulin, and has been implicated in glycoprotein folding 25.

ERp5

ERp5, encoded by the gene PDIA6, has a molecular weight of 48,000 and includes 440 amino acids. It is composed of three thioredoxin-like domains a-a’-b, where a and a’ are active thiol isomerases with the CGHC motif in the active site, and are preceeded by a signal sequence. The C-terminal segment contains the KDEL sequence that binds to the KDEL receptor. This enzyme is broadly expressed in cells from a spectrum of tissues. Within the cell, this enzyme is primarily involved in the formation and rearrangement of disulfide bonds.

Storage and secretion of thiol isomerases in platelets and endothelial cells

The observation that antibodies to thiol isomerases block thrombus formation indicates that extracellular thiol isomerases participate in thrombus formation. The subcellular localization of thiol isomerases and, in particular, thiol isomerase localization to the plasma membrane is an essential feature of their participation in blood coagulation. Thiol isomerases typically localize to the endoplasmic reticulum. PDI, for example, is highly enriched in endoplasmic reticulum, with an estimated concentration of 200 μM 26. Such enrichment of thiol isomerases is achieved by the endoplasmic reticulum retention machinery. The KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence at its C-terminus is recognized by a member of the KDEL receptor family located in the Golgi 27. The receptor mediates the recycling of the protein back to the endoplasmic reticulum. ERp57 and ERp72 contain QDEL and KEEL endoplasmic reticulum retention sequences, respectively. Despite this mechanism for endoplasmic reticulum retention, localization of thiol isomerases to the Golgi apparatus, secretory granules, and on plasma membrane following secretion is observed in many cell types 28 and extracellular thiol isomerases mediate numerous biological functions in addition to thrombus formation 29-34.

How do extracellular thiol isomerases escape the endoplasmic reticulum retrieval mechanism? One possibility is that non-ER thiol isomerases are either splice variants that lack the ER retention sequence or proteolytic products from which the ER retention sequence has been removed. Yet secreted thiol isomerases retain their ER retention sequence. In hepatocytes and exocrine pancreatic cells the KDEL sequence is identified in PDI localized to the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane 35, 36. Saturation of the ER retention machinery has been proposed as a mechanism by which thiol isomerases escape retrieval to the ER 37. Another possibility is that thiol isomerases escape ER retention by complex formation with other proteins that prevent the interaction of thiol isomerases with KDEL family receptors 38. Both facultative translocation in which PDI is partitioned between cytosolic and ER compartments 39 and retrotranslocation 40 have been proposed 41. More recently, a KDEL receptor-dependent pathway that traffics PDI from the Golgi to the plasma membrane has been identified in endothelial cells 42. This pathway is dependent on KDEL receptor-mediated activation of src kinases 43, 44 and is blocked by knockdown of the KDEL receptor or inhibition by brefeldin A, an inhibitor of ER-Golgi trafficking 28, 42. This pathway could provide a mechanism for thiol isomerases transport to either the cell surface or to secretory granules.

The observation that thiol isomerases localize both to secretory granules and to the plasma membrane indicates that they can partition to either regulated or constitutive secretory pathways. However, the mechanisms that underlie the partitioning are not well understood. To appreciate the implications of subcellular localization of thiol isomerases for thrombus formation, one must consider subcellular localization in vascular cells including platelets and endothelial cells.

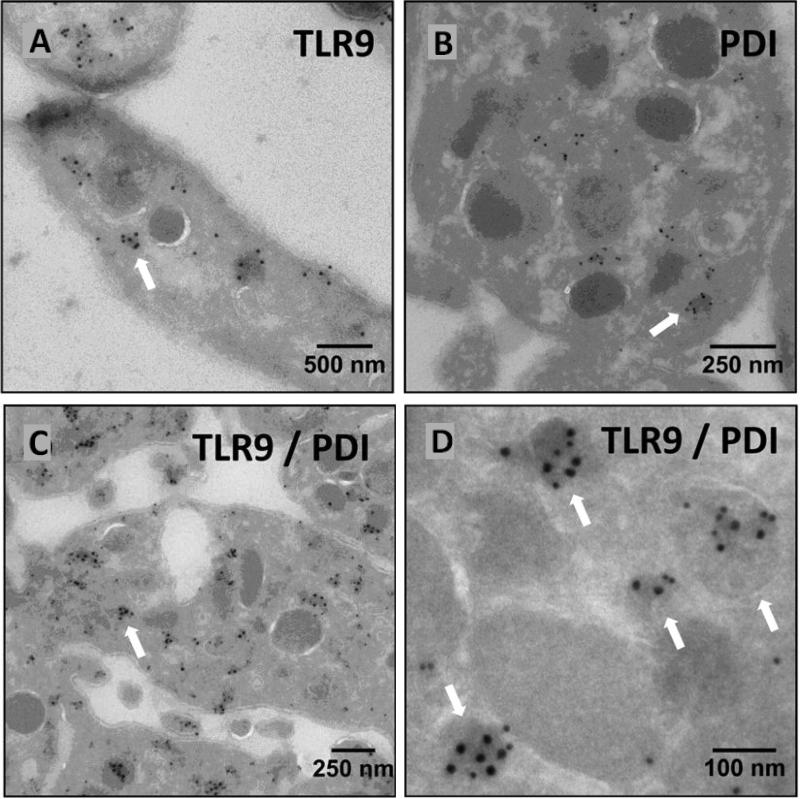

Platelet thiol isomerases are stored in intracellular compartments and are released upon activation. Chen et al. demonstrated PDI in the supernatants of activated platelet over 20 years ago 5. Many other reports confirmed that PDI is released from activated platelets. Whether or not PDI localizes to the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane of resting platelets has been more difficult to assess, since it is difficult to rule out activation during processing as a source of surface PDI. The observation that PDI is released in an activation-dependent manner raises the question of what granule type PDI is stored in prior to release. The major secretory granules in platelets are α-granules (50-80/platelet), dense granules (3-6/platelet), and lysosomes (0-3/platelet) 45. PDI showed a normal distribution in platelets from subjects with gray platelet syndrome, which lack α-granules, and in platelets from subjects with Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome, which lack dense granules 46. These results indicated that PDI is not stored primarily in dense or α-granules. In contrast to nucleated cells that store the majority of their PDI in the ER, platelets do not have a mature ER. They do have a dense tubular system, which is considered a remnant of the ER 47. However, the dense tubular system is not considered a secreted compartment. Nonetheless, we recently identified PDI in platelet T-granules, a newly defined electron dense tubular system-related granular compartment that contains TLR9 and PDI (Fig. 3) 46. T-granules are released in an activation-dependent manner. How PDI is released from T-granules remains an area of active investigation. Whether or not T-granules represent the storage site of other platelet thiol isomerases also remains to be determined.

Figure 3. Co-localization of PDI with TLR9 in T-granules.

Electron microscopy demonstrates (A) TLR9, (B) PDI, or (C and D) co-localization of both TLR9 and PDI to electron-dense membrane-encapsulated regions adjacent to the plasma membrane of platelets.

Endothelial cell thiol isomerases have been identified in several subcellular compartments, and the distribution of PDI is best established. Both microscopy 48, 49 and density gradient centrifugation 9 show that endothelial PDI is concentrated in the ER. Several experiments, however, indicate that PDI also resides on the surface of endothelial cells. Immunolocalization of PDI on nonpermeabilized endothelial cells demonstrated its cell surface localization 50. Endothelial PDI also colocalizes with plasma membrane markers when analyzed by density gradient centrifugation 9. PDI has been identified by mass spectrometry of a highly purified endothelial cell plasma membranes preparation. In addition 51, surface labeling of endothelial cells with sulfosuccinimidobiotin followed by streptavidin precipitation demonstrated endothelial cell surface PDI 22. Functional assays also indicate the presence of PDI on the extracellular surface of endothelial cells. Endothelial cell surface PDI participates in transnitrosation of proteins 52, 53 and in modifying cell surface αVβ354. Additional PDI is released from endothelial cells upon stimulation by agonists such as thrombin, PMA or calcium ionophore 9, suggesting that it is stored in secretory granules. Co-localization studies showed that PDI does not localize to Weibel-Palade bodies, but is found in chemokine-containing, small secretory granules co-localized with GRO-α and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 9. The mechanism by which these small secretory granules are exocytosed upon stimulation is not well-defined.

Real-time monitoring of thrombus formation in live mice using intravital microscopy demonstrates that thiol isomerases are rapidly released following vascular injury. Laser-induced injury of cremaster muscle arterioles results in rapid accumulation of PDI at the site of injury 8. The appearance of PDI precedes the accumulation of platelets. Studies in which platelet accumulation is inhibited proved that the PDI that is rapidly release following vascular injury is derived from endothelium, though secretion from platelets contributes as they accumulate over time 9. Once released at the site of injury, PDI is captured by endothelial αvβ3 and platelet αIIbβ355. ERp57 also accumulates at sites of vascular injury and is required for thrombus formation 20. Since thiol isomerase release is essential for its function in thrombus formation, it is possible that defects in granule secretion could result in decreased thiol isomerase release and impaired thrombus formation. It is also possible that pharmacological blockade of PDI release could impair thrombus formation. Such possibilities have yet to be explored.

A critical and unanticipated role for thiol isomerases in thrombus formation in vivo

PDI, the prototypic thiol isomerase of the PDI family

Although PDI has been known to be secreted from platelets and to be present on the platelet membrane surface for several decades 5 and inhibitors of thiol isomerases were known to alter platelet aggregation 10 and fibrinogen interaction with the platelet integrin αIIbβ356 in vitro, the biological importance of these earlier observations were not appreciated until the demonstration in in vivo mouse models of thrombosis that inhibition of PDI inhibited thrombus formation 8, 19. In one study, thrombus formation in the cremaster arterioles was monitored by intravital microscopy, and PDI antigen secretion into the blood following laser-induced vascular injury was visualized. This PDI became associated with the growing thrombus. Inhibition of PDI with a blocking antibody completely inhibited both platelet thrombus formation and fibrin generation. In the other study, thrombus formation was initiated with a ligation injury. Fibrin, visualized by intravital microscopy, was significantly attenuated by infusion of an inhibitory antibody to PDI 19. Both studies, using different vascular injury models, allowed the conclusion that fibrin generation is dependent on the presence of PDI. Following vascular injury, PDI is first secreted from the endothelium and then secreted from the bound platelets 8, 9.

Both the endothelium and platelets contribute to the generation of extracellular PDI. The kinetics of appearance of PDI during thrombus formation indicate that, prior to the deposition of platelets, PDI lines the area of vascular injury 8. This strongly implicates the endothelium as the initial source of PDI. If platelets are blocked from participating in thrombus formation using eptifibatide, and thus the platelet contribution of PDI eliminated, PDI accumulates on the injured vessel wall due to secretion from the endothelium 9. Genetically modified mice lacking platelet PDI initially demonstrated platelet adhesion and fibrin formation 57, consistent with the importance of the endothelium contribution of extracellular PDI.

Does platelet-derived PDI differ in function from endothelium-derived PDI? Jasuja et al demonstrated that, in the absence of platelets and thus the absence of platelet-derived PDI, fibrin generation is normal despite the absence of platelet accumulation 9. In a parallel series of experiments with the exception that platelets were present, Kim et al showed that in genetically modified mice lacking platelet PDI, platelet PDI is critical for thrombus growth but is not required for initial platelet adhesion 57. This is likely supported by endothelial PDI. Platelet-derived PDI is specifically not required for P-selectin expression, calcium mobilization, certain phosphorylation reactions, β3-talin interaction and platelet spreading, as might be expected a priori 57.

PDI binds to the active conformer of the β3 integrin subunit 55. The prominent platelet integrin αIIbβ3 is located solely on platelets. Upon activation and a conformational transition, this integrin binds to fibrinogen. αVβ3 is located on the endothelium, although there is modest expression on platelets as well. This integrin is a vitronectin receptor, although other protein ligands also interact with it 58, 59. PDI binds to the β3 subunit with a Kd of about 1-2 μM 55. The fact that the binding constant is about the same for both αIIbβ3and the β3 subunit suggests that PDI interacts predominantly with theβ3 subunit. The interaction between PDI and the β3 subunit requires the active conformer of β3—a form stabilized in the presence of Mn2+. No interaction was observed in the presence of EDTA.

Earlier in vitro studies have pointed to the role of thiol isomerases and their inhibitors in the activation or inhibition of integrin function. For example, αIIbβ3 exposes free sulhydryl groups during platelet activation 60, 61. The addition of anti-PDI antibodies to platelets blocks specific platelet functions attributed to both αIIbβ3 and αVβ1 56, 62. If these integrins were substrates of PDI, αIIbβ3 would have to have free sulhydryls. Yet, the crystal structure of human αIIbβ3 does not show any free sulhydryls 63; all 56 cysteines form 23 disulfide bonds in β3. Nonetheless, mutation of specific cysteine residues can convert αIIbβ3 into its active conformer that binds to fibrinogen 64-66. Furthermore, αIIbβ3, with nine CXXC motifs, has endogenous thiol isomerase activity 67. These Cys residues are engaged in disulfide bonds and thiol isomerase activity requires two free sulhydryls in the CXXC motif. The key question is whether some of these disulfide bonds break spontaneously, for brief intervals, as the protein “breathes,” and crystallography only captures the major oxidized structure. The mechanism of αIIbβ3 activation, be it involve thiol isomerases or the cytoplasmic tails of the integrin subunits and inside-out signaling 68, remains elusive.

PDI is essential for platelet thrombus formation and fibrin generation in vivo 8, 9, 19, 57. In its absence, neither platelets aggregate nor fibrin forms in the injured vascular bed. An unexplained observation has been that β3 null mice demonstrated no fibrin generation in vivo 55, which was unanticipated given that wild type mice treated with eptifibatide that blocks platelet accumulation and Par4 null mice with platelets that can not be activated by thrombin, generate normal levels of fibrin despite the absence of platelet thrombi 9, 69. All three of these mice—β3 null, Par4 null and wildtype mice treated with eptifibatide—fail to generate a platelet thrombus in vivo. A major difference is that only β3 null mice lack αVβ3 in the endothelium. Perhaps β3, in either αVβ3 or αIIbβ3, is a critical intermediate in the initiation pathway to fibrin formation? This poses a potential important role for PDI in fibrin formation.

Kim et al proposed that PDI is essential for thrombus formation but not for maintaining hemostasis 57. This conclusion was based on the observation that the tail bleeding times in mice lacking PDI within platelets were normal whereas mice in which all extracellular PDI was inhibited using a blocking antibody had prolonged bleeding times 8. However, this conclusion requires an assumption that hemostasis, the host defense system for maintaining the integrity of a high pressure circulatory system, can be predicted from the bleeding time. Several arguments question this conclusion. First, the bleeding time in humans has essentially been abandoned as a clinical predictor of bleeding risk 70. Second, even some mice known to have a severe bleeding tendency, such as those lacking Factor VIII, can express a normal tail bleeding time 71. We too have demonstrated that an inhibitor of PDI, isoquercetin, administered to mice does not increase the tail bleeding time 72. However, we do not conclude based on this observation that hemostasis is preserved. Unfortunately, there are limited experimental approaches to the evaluation of hemostasis in laboratory animals.

ERp57, a protein whose domain architecture parallels PDI

ERp57 has been shown by three independent groups to be important for thrombus formation in vivo 11, 13, 14, 19, 20. Antibodies to ERp57 inhibited platelet aggregation, fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3, dense granule secretion and P-selectin expression in vitro in one study but not the other 11, 20. An inhibitory anti-ERp57 antibody prolonged the bleeding time in mice and inhibited thrombosis in the ferric chloride-induced injury model applied to the carotid artery 11 and the laser-induced injury model applied to the cremaster muscle 20. Given the marked sequence and structural similarity between ERp57 and PDI, the problem of antibody cross-reactivity poses a significant concern in assigning particular functions to these thiol isomerases. Although a polyclonal antibody to ERp57 inhibited some degree of PDI activity, Wu et al generated a monoclonal antibody to ERp57 that appears to be highly specific for ERp57 11. They also demonstrated that a widely used monoclonal antibody RL90 directed at PDI shows significant cross-reactivity to ERp57. Using translation blocking antisense Vivo-morpholinos targeted to ERp57 (Vivo-ERp57) that reduced ERp57 expression in mouse tissues, Jasuja et al extended these studies to demonstrate that ERp57 is released from both platelets and endothelial cells 13. Laser-induced platelet thrombus formation and fibrin accumulation were significantly decreased in Vivo-ERp57-treated mice. Platelet thrombus formation was absent after laser injury in mice with a platelet-specific deletion of ERp57 but fibrin generation is normal. Thus ERp57 secreted from endothelial cells at sites of laser injury does not rescue platelet thrombus formation in mice lacking platelet ERp57.

Anti-ERp57 antibodies inhibit the activation of αIIbβ3 11 . Similarly, catalytically inactive ERp57 inhibited platelet aggregation and prolonged the tail bleeding time in mice 11. A mouse model lacking megakaryocyte/platelet ERp57 similarly had prolonged tail bleeding times and prolonged times to occlusion using the ferric chloride-induced carotid injury model 14. Platelets lacking ERp57 showed partial defects in aggregation, a defect that could be rescued with the addition of exogenous ERp57. There was decreased platelet incorporation into the growing thrombus in the mesentery model of thrombus formation using ferric chloride. Of the two catalytically active domains, the second a’ domain appears to bind to and trigger activation of αIIbβ3, leading to expression of a conformation-specific activation epitope and enhanced fibrinogen binding. If confirmed that the tail bleeding time in mice is prolonged in the absence of platelet-specific ERp57 but normal in the absence of platelet-specific PDI 57, this will provide evidence for different roles of platelet PDI and ERp57.

ERp5

Like PDI and ERp57, ERp5 is secreted from platelets upon cell activation 10. Inhibition of ERp5 function with an anti-ERp5 antibody prevented fibrinogen binding to activated platelets and platelet aggregation in vitro 10. The fibrinogen receptor αIIbβ3 is a potential substrate of ERp5 as the enzyme co-immunoprecipitates with the β3 chain of the integrin 10. We investigated if ERp5 is released at the site of thrombus formation in vivo and whether inhibition of the reductase activity of ERp5 influences platelet thrombus formation and fibrin generation in a laser-induced mouse model of thrombosis 12. Anti-ERp5 antibody inhibited ERp5-dependent platelet- and endothelial cell disulfide reductase activity in vitro and laser-induced thrombus formation in vivo, with a significant decrease in the deposition of platelets and in fibrin accumulation. ERp5 binds to wild type αIIbβ3 but does not bind to a mutant αIIbβ3 which is unable to bind fibrinogen. ERp5 binds to β3 with a Kd of 6.9 μM. These results provide evidence for a novel role of ERp5 in thrombus formation.

These studies have established several common features of PDI, ERp57 and ERp5. First, the active site motif is characterized by CGHC in all of the catalytically active domains of these enzymes. It is thought that the redox potential of these thioredoxin-like domains is defined by the XX within the CXXC motif. This would argue that the redox potentials are similar in these three enzymes whereas sequences of the b and b’ domains are quite different, and likely responsible for the potential variety of substrate specificities. Second, PDI, ERp57 and ERp5 all bind to αIIbβ3. Direct binding studies of PDI to αIIbβ3 and β3 indicate a Kd of 1-2 μM 55; direct binding studies of ERp5 to αIIbβ3 and β3 indicate a Kd of about 7 μM 12. In both cases, blocking antibodies to the thiol isomerase leads to inhibition of platelet aggregation and blockade of activation of αIIbβ3. In the case of ERp57, ERp57 also appears to interact with β314, although direct binding experiments have not been performed. Third, αIIbβ3 appears to be a central actor in the pathway to both platelet activation and fibrin generation. However, the mechanism by which these three isomerases interact with active αIIbβ3, either directly or indirectly, remains to be determined.

Potential substrates of thiol isomerases during thrombus formation

A method for identifying substrates of extracellular vascular thiol isomerases based upon mechanism-based kinetic trapping of extracellular PDI substrates has been developed. The basic approach, employed for determining the electron transport pathway in the ER 73 and on cell surfaces 74, was modified in order to study mixed disulfides involving thiol isomerases and their covalently bound substrates that originate in plasma and platelet releasate. The redox function of thiol isomerases is dictated by the state of the CXXC motif of the active site. For almost all of the thiol isomerases identified to date that are associated with the platelet, this motif is CGHC in the active thioredoxin-like domain. When the enzyme active site CXXC is reduced, a substrate disulfide can be reduced and the thiol isomerase active site becomes oxidized. When the enzyme CXXC is oxidized, the disulfide can be transferred to the substrate while the CXXC active site is reduced. These reactions occur through transient formation of a mixed disulfide between the N-terminal Cys in the enzyme CXXC motif and a free Cys in the substrate. Resolution of the mixed disulfide requires the enzyme C-terminal Cys in the CXXC active site to attack the disulfide bond, leading to two free sulhydryl residues 75. Mutation of this C-terminal Cys in the enzyme active site to CXXA prevents cleavage of the mixed disulfide, and the enzyme-substrate complex linked by a disulfide bond remains stable 73. Identification of the protein bound to the thiol isomerase by mass spectrometry and western blotting reveals a substrate that requires a thiol isomerase active site. A thiol isomerase-substrate complex that interacts independent of the enzyme active site can be identified using an AXXA mutation since this active site motif cannot form a mixed disulfide with the substrate.

The PDI cDNAs of the wild-type; a PDI with a modified active site leading to covalent interaction with a substrate (“trapping mutant”) with alanine substitutions of the C-terminal Cys at the a- or a’-domains (C56A,C400A); and an inactive control mutant containing alanine substitutions at all active site Cys residues in both the a- and a’-domains (C53,56,397,400A) were cloned and expressed with an N-terminal FLAG-epitope and a C-terminal streptavidin binding peptide (SBP)-epitope. To identify PDI substrates in platelet-rich plasma, wild type PDI-CGHC, the trapping mutant PDI-CGHA and the inactive PDI-AGHA, all containing both the FLAG- and SBP-tag, were reacted with components of platelet-rich plasma. PDI and any PDI-substrate complexes is immunoprecipitated using streptavidin-agarose beads that bind the SBP-tag on the PDI, then eluted using biotin. Our results indicate that he trapping mutant is reactive with multiple protein substrates in both plasma/platelet releasate and platelet lysate. Protein bands resolved by SDS-PAGE candidate PDI substrates identified by mass spectrometry and confirmed by Western blot using an antibody specific for that identified PDI substrate. To date, thrombospondin-1 has been identified as PDI substrates on platelet membranes.

To identify PDI substrates undergoing reduction, oxidation or isomerization, the GH residues of the PDI active site, CGHC, was mutated. Some of these mutations resulted in active PDI variants with altered kinetics of enzyme-substrate interaction, resulting in stable reaction intermediates with enzyme covalently linked to the substrate 76. Two GH variants trapped proteins in platelet releasate. Because enzymatically active PDI is required for thrombus formation, only those substrate proteins that bound to the enzymatically active variant PDI, and not to an enzymatically inactive PDI were analyzed further. Of the PDI-associated proteins identified in releasate, only multimerin-1 and factor V were covalently bound to PDI through a disulfide bond. Multimerin-1 and platelet factor V are reported to be in a disulfide-linked complex in platelet α-granules 77. These data suggest a role for PDI in the early stages of thrombus formation, where PDI is required for platelet factor V release from multimerin-1, allowing formation of the prothrombinase complex, and generation of necessary levels of thrombin for initial platelet-dependent thrombin generation.

Control of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species by thiol isomerases

In addition to their oxidoreductive activities, thiol isomerases can react with nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The ability of thiol isomerases to transfer NO to a target protein, remove NO from a protein, and to transfer NO from the extracellular environment into the cytosol have all been documented 52, 53, 78, 79. Thiol isomerases have also been shown to bind to NADPH oxidase and facilitate ROS production in vascular cells 80. NO and ROS serve critical roles in the thrombus formation and the ability of thiol isomerases to control NO and ROS is an important consideration in understanding the role of thiol isomerases in thrombus formation.

The same catalytic cysteines that mediate the oxidoreductive activities of PDI can be subjected to S-nitrosylation at physiological NO levels. S-nitrosylation of recombinant PDI occurs at both of its two catalytic domains. PDI mutants in which cysteines were replaced with serines in either the N-terminal CXXC motif or the C-terminal CXXC motif each demonstrated 50% of the S-nitrosylation of wild-type PDI when incubated with an NO donor 81. S-nitrosylation did not occur when both CXXC motifs were mutated. Thus, S-nitrosylation of PDI occurred only at the active site cysteines. Functional studies showed that S-nitrosylation of recombinant PDI inhibits both its chaperone activity and its isomerase activity 81. S-nitrosylation of PDI has physiological consequences. Increased levels of S-nitrosoylation were identified in brain slices of patients with Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease and overexpression of wild-type PDI protects neurons from death is several models of neurodegeneration 81, 82.

PDI and NO also interact in the vasculature. Proteomics studies have identified S-nitrosylated PDI in endothelium and shown increased PDI S-nitrosylation with statin use 83, shear stress 84, or hypoxia 85. The inhibition of PDI by NO could contribute to vascular quiescence. PDI may further facilitate the ability of NO to maintain vascular quiescence by transferring NO from the extracellular environment into cytosol. The original studies demonstrating that PDI regulates the transfer of NO into cytosol were performed in human erythroleukemia cells 78. Knockdown of PDI by antisense mRNA resulted in a substantial decrease in NO-mediated cGMP generation after S-nitrosothiol exposure. Subsequent studies in endothelial cells demonstrated that cell surface PDI transferred NO from S-nitroso-albumin, the major NO carrier in plasma 86, to endothelial cell cytosol 52. Knockdown of cell surface PDI in endothelial cells inhibited transfer of NO from extracellular S-nitroso-albumin to cytosolic proteins such as metallothionein 53.

PDI can also transfer NO into platelets. Incubation of platelets with an NO donor results in increased fluorescence of an NO-sensitive intracellular probe 87. Inhibition of cell surface PDI using a PDI-specific antibody blocked the increased fluorescence 87, 88. Once introduced into the platelet cytosol, NO can interact with soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC). sGC is a heme-containing protein and NO binds avidly to the porphyrin ring, activating the enzyme 89. When accumulation of NO into platelet cytosol was blocked by inhibition of PDI, cGMP synthesis was inhibited 87. NO serves an essential role in maintaining vascular quiescence 90. Although platelets possess nitric oxide synthetase (NOS) 91, 92, transfer of NO from endothelial cells is considered the major source of NO in the vasculature 90, 93. PDI-mediated transfer of NO produced by the endothelium and transferred into platelet cytosol could help regulate platelet activation.

While platelet and endothelial cell PDI facilitate maintenance of quiescence in the resting blood vessels, several changes occur with cell activation that could reverse the role that PDI has in controlling vascular NO and ROS. NO levels decrease as a result of endothelial dysfunction and may decrease acutely during thrombus formation 94. Furthermore, reduced PDI that is secreted from platelets and endothelial cells during thrombus formation could remove NO from S-nitrosylated proteins. Reduced PDI is capable of removing NO from S-nitrosoglutathione 79, 95 as well as target proteins including S-nitroso-albumin 53 and S-nitroso-PDI 79.

Another mechanism by which PDI could contribute to thrombus formation is by facilitating the generation of ROS. PDI physically associates with NAPDH oxidase, a major source of ROS in platelets and endothelial cells 96-98. Co-immunoprecipation studies demonstrate that PDI associates with the NADPH oxidase subunits p223phox, Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 99. This association is not dependent on the active site cysteines since overexpression of PDI with serine mutations in all four redox cysteines promoted spontaneous NADPH oxidase activity comparable to wild-type PDI 100.

The association of PDI with NADPH oxidase results in increased production of ROS. Inhibition of PDI in several cell types blocks ROS production. In vascular smooth muscle cells, agonists that increase ROS production stimulated a shift of PDI towards membranes 99. Exposure of isolated membranes to PDI inhibitors or neutralizing antibody to PDI blocked NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production. Knockdown of PDI in vascular smooth muscle cells using siRNA also inhibited ROS production 100. Neutralizing antibodies to PDI inhibited ROS production in endothelial cells 80. PDI was shown to associate with neutrophil 101 and macrophage 33 NADPH oxidase and augment generation of ROS. A role for PDI in enhancing NADPH oxidase activity in platelets has not yet been evaluated. .

Thiol isomerases as drug targets

Arterial thrombosis, the underlying cause of myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The fact that current antithrombotic therapies are insufficient is evidenced by the high rate of recurrent thrombosis despite convention treatment 102, 103. Alternative antithrombotic strategies based on new knowledge of in vivo thrombus formation are required to improve antithrombotic therapy. Thiol isomerases represent an important class of antithrombotic targets. Pre-clinical studies performed using different murine models of thrombus formation consistently indicate that PDI functions in thrombus formation 8, 9. These murine models demonstrate that inhibition of thiol isomerases block both platelet accumulation and fibrin formation at sites of vascular injury 8, 104. ERp57 has also been shown to participate in thrombosis11, 14, 20, 57. These pre-clinical studies demonstrate the efficacy of thiol isomerase inhibition in the setting of thrombosis.

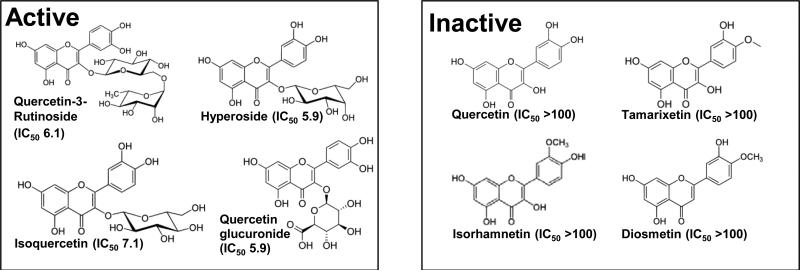

Yet can thiol isomerases be inhibited without significant toxicity given their role in protein folding? The most compelling studies to address this question are a series of experiments performed using quercetin-3-rutinoside. Quercetin-3-rutinoside was identified as an inhibitor of PDI while screening a library of bioactive compounds with known activities 104. Structure function studies showed that not only did quercetin-3-rutinoside inhibit PDI function, but all other quercetin flavonoids tested that possessed a 3-O-glycosidic linkage at the 3’ position of the C ring blocked PDI activity (Fig. 4). Quercetin flavonoids that lacked this sugar failed to inhibit PDI. This same glycosidic linkage that endows a quercetin flavonoid with the ability to inhibit PDI likely impairs its cell permeability.

Figure 4. Inhibition of PDI by quercetin flavonoids with a 3-O-glycosidic linkage.

High throughput screening identified quercetin-3-rutinoside as an inhibitor of PDI. Subsequent studies evaluating structure activity relationships demonstrated that a sugar at 3’ position in the C ring of quercetin-3-rutinoside is critical for its ability to inhibit PDI. All analogs tested with a sugar in this position inhibited PDI (Active), while analogs lacking this sugar failed to demonstrate inhibition (Inactive).

Quercetin-3-rutinoside blocked thrombus formation in mice following laser-induced injury or ferric chloride-induced damage of cremaster arterioles 104. In contrast, a quercetin flavonoid that lacked the 3-O-glycosidic linkage, diosmetin, neither inhibited PDI activity nor blocked thrombus formation in vivo. Furthermore, infusion of recombinant PDI reversed quercetin-3-rutinoside inhibition, demonstrating that PDI was indeed the relevant target of its antithrombotic activity 104. Quercetin-3-rutinoside demonstrated antithrombotic activity regardless of whether it was administered intravenously or by oral gavage 104.

Quercetin flavonoids are abundant in commonly ingested fruits, vegetables, teas, and grains. Quercetin-3-rutinoside is also widely available as an over the counter nutritional supplement. These compounds have been designated Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status by the FDA.

The evidence that PDI inhibition is both effective at blocking thrombus formation and safe raises the question of what antagonists should be used in the clinical setting. Many PDI inhibitors have been described. These include synthetic reagents that act at the catalytic cysteines, plant metabolites, antibiotics such bacitracin, and hormones such as estrogens and thyroid hormones 105. However, only the plant metabolites and synthetic compounds have adequate efficacy and safety for use as antithrombotics.

The plant metabolites shown to inhibit PDI include juniferdin and quercetin flavonoids with 3-O-glycosidic linkages such as quercetin-3-rutinoside and isoquercetin. Juniferdin was identified in a high throughput screen designed to identify inhibitors of PDI reductase activity using an insulin-based turbidimetric assay 106. The goal was to identify novel therapies targeting HIV-1, which requires PDI for entry into cells 29, 107. Juniferdin itself demonstrated cytotoxicity in cultured cells. However, among several analogs that were tested, juniferdin epoxide retained PDI inhibition and did not demonstrate substantial cytotoxicity in cultured cells.

Many synthetic compounds that block PDI activity have been identified. The majority are sulfhydryl reagents that have long been used to study PDI in protein-based and cell-based assays, but lack adequate potency and/or selectivity for clinical use. More recently, several more potent synthetic small molecules have been identified. 16F16 was discovered in a screen to identify compounds that suppress apoptosis 108. It is thought to bind active site cysteines and demonstrates cytotoxicity that may be related to off-target effects 109. RB-11-ca is interesting as a chemical probe because of its target selectivity: it covalently binds to Cys53 of PDI and not other vicinal cysteines 110. A phenyl vinyl sulfonate-containing compound developed as an anti-neoplastic was found to inhibit PDI with a potency in the low micromolar range and was cytotoxic in several cancer cell lines 109. PAMCA-31 is a cell-permeable propynoic acid carbamoyl methyl amide that was also cytotoxic to cancer cells. When tested in mice, PACMA-31 blocked ovarian tumor growth without causing toxicity to normal tissue 111. Oral dosing in these studies escalated to 200 mg/ml PACMA-31 and continued for 62 days without significantly effecting body weight or histology in major organs. The synthetic compounds mentioned above are all characterized by electrophilic moieties susceptible to covalent attack by the highly nucleophilic cysteine residues in the PDI active sites. As such, they are all irreversible inhibitors of PDI.

We have begun a trial in human subjects evaluating the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of isoquercetin. However, quercetin flavonoids are not without shortcomings as antithrombotics. They are poorly absorbed and their absorption and metabolism is highly variable between individuals. Although they are selective for PDI among thiol isomerases and failed to inhibit ERp57, ERp5, ERp72, or thioredoxin reductase 104, they are highly hydprophobic and have alternative targets. More potent reversible PDI inhibitors with improved pharmacokinetics and selectivity may provide for a second generation of antithrombotic PDI inhibitors and such compounds are presently in development.

Conclusion

Platelet-mediated thrombus formation is a highly complex process influenced by multiple cell types, plasma factors, bioactive mediators, reactive oxygen species, and physical forces. Unlike in vitro models that typically focus on only few parameters, animal models of thrombus formation incorporate all these components. Although in vivo models have limitations, they provide information not easily ascertained by in vitro studies. The identification of thiol isomerases as important components of thrombus formation is a notable example of the utility of studying thrombus formation in vivo. While in vitro studies have provided inconsistent results with regard to the role of thiol isomerases in coagulation, in vivo studies have consistently demonstrated their importance in both platelet accumulation and fibrin generation following vascular injury.

The evidence that inhibition of thiol isomerases blocks thrombus formation is sufficiently strong that the PDI inhibitor isoquercetin has already entered clinical trials (NCT1722669). The number of other small molecule inhibitors of PDI has increased substantially in recent years. Many of these are far superior as biological probes with regard to potency and selectivity compared with inhibitors that have been used for decades as thiol isomerases inhibitors such as bacitracin and DTNB. However, whether these other recently reported thiol isomerase antagonists are viable drug candidates remains to be determined. Since thiol isomerase inhibition blocks both platelet accumulation and fibrin generation, thiol isomerase inhibitors could be used either in the setting of arterial thrombosis or venous thrombosis.

Improved understanding of the mechanism by which thiol isomerases participate in platelet recruitment and fibrin generation will help guide the selection of clinical settings in which to test this new class of antithrombotics. Yet little is known about how thiol isomerases mediate thrombosis or which thiol isomerases represent the best drug targets. The ability of these enzymes to interact with and modify multiple substrates suggests that they do not act on only a single component of the coagulation cascade or on a single platelet receptor, but rather act as regulators that act on many substrates. The challenge will be to identify those thiol isomerase-substrate interactions that are critical for thrombus formation.

Supplementary Material

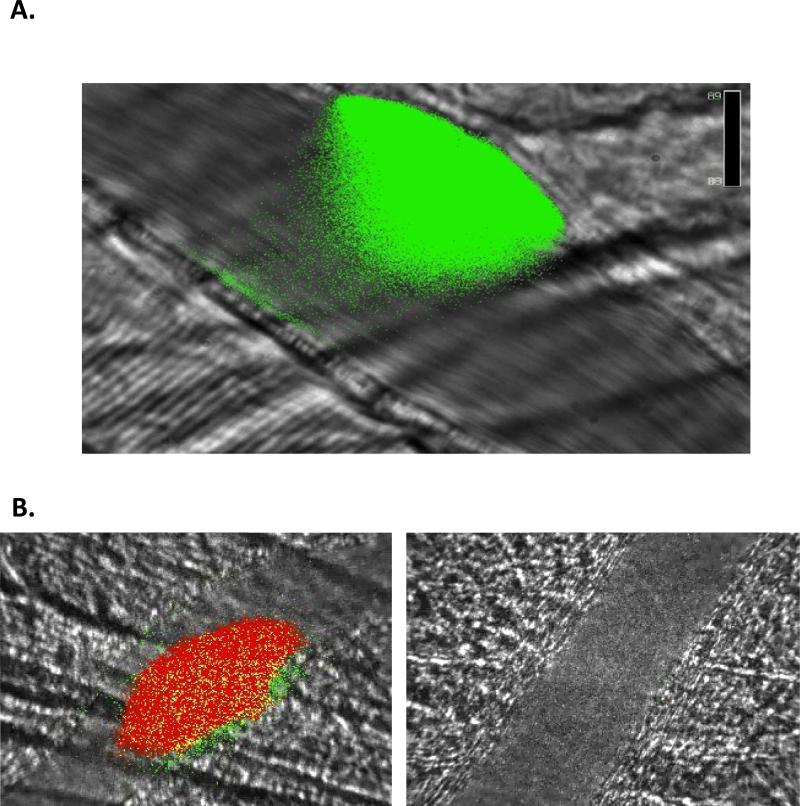

Figure 2. PDI is released during and is required for thrombus formation.

Intravital microscopy images of thrombus formation in a live mouse. A. PDI antigen (green) is secreted from platelets and endothelium during thrombus formation. B. Blocking anti-PDI antibody inhibits platelet thrombus formation (red) and fibrin (green) generation. Left, 0 μg/g mouse; right, 3.0 μg/g mouse. Time of images: 60 seconds post-injury.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: NIH

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- PDI

Protein disulfide isomerase

- ADP

arachnadonic acid

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Givol D, Goldberger RF, Anfinsen CB. Oxidation and disulfide interchange in the reactivation of reduced ribonuclease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1964;239:PC3114–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lorenzo F, Goldberger RF, Steers E, Jr., Givol D, Anfinsen B. Purification and properties of an enzyme from beef liver which catalyzes sulfhydryl-disulfide interchange in proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1966;241:1562–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galligan JJ, Petersen DR. The human protein disulfide isomerase gene family. Hum Genomics. 2012;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaux D, Tooze J, Fuller S. Identification by anti-idiotype antibodies of an intracellular membrane protein that recognizes a mammalian endoplasmic reticulum retention signal. Nature. 1990;345:495–502. doi: 10.1038/345495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K, Lin Y, Detwiler TC. Protein disulfide isomerase activity is released by activated platelets. Blood. 1992;79:2226–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K, Detwiler TC, Essex DW. Characterization of protein disulphide isomerase released from activated platelets. Br J Haematol. 1995;90:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essex DW, Chen K, Swiatkowska M. Localization of protein disulfide isomerase to the external surface of the platelet plasma membrane. Blood. 1995;86:2168–2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho J, Furie BC, Coughlin SR, Furie B. A critical role for extracellular protein disulfide isomerase during thrombus formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1123–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI34134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasuja R, Furie B, Furie BC. Endothelium-derived but not platelet-derived protein disulfide isomerase is required for thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:4665–4674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan PA, Stevens JM, Hubbard GP, Barrett NE, Sage T, Authi KS, Gibbins JM. A role for the thiol isomerase protein erp5 in platelet function. Blood. 2005;105:1500–1507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Ahmad SS, Zhou J, Wang L, Cully MP, Essex DW. The disulfide isomerase erp57 mediates platelet aggregation, hemostasis, and thrombosis. Blood. 2012;119:1737–1746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passam F, Lin L, Huang M, Furie B, Furie BC. Role of thiol isomerase erp5 in thrombus formation. 2013 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jasuja R, Sharda A, Kim SH, Furie B, Furie BC. Endothelial erp57 has a critical role in fibrin generation but not platelet accumulation in a mouse model of thrombosis. 2013 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Wu Y, Zhou J, Ahmad SS, Mutus B, Garbi N, Hammerling G, Liu J, Essex DW. Platelet-derived erp57 mediates platelet incorporation into a growing thrombus by regulation of the alphaiibbeta3 integrin. Blood. 2013;122:3642–3650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:938–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falati S, Gross P, Merrill-Skoloff G, Furie BC, Furie B. Real-time in vivo imaging of platelets, tissue factor and fibrin during arterial thrombus formation in the mouse. Nat Med. 2002;8:1175–1181. doi: 10.1038/nm782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgess JK, Hotchkiss KA, Suter C, Dudman NP, Szollosi J, Chesterman CN, Chong BH, Hogg PJ. Physical proximity and functional association of glycoprotein 1balpha and protein-disulfide isomerase on the platelet plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9758–9766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holbrook LM, Watkins NA, Simmonds AD, Jones CI, Ouwehand WH, Gibbins JM. Platelets release novel thiol isomerase enzymes which are recruited to the cell surface following activation. British journal of haematology. 2010;148:627–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhardt C, von Bruhl ML, Manukyan D, Grahl L, Lorenz M, Altmann B, Dlugai S, Hess S, Konrad I, Orschiedt L, Mackman N, Ruddock L, Massberg S, Engelmann B. Protein disulfide isomerase acts as an injury response signal that enhances fibrin generation via tissue factor activation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:1110–1122. doi: 10.1172/JCI32376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holbrook LM, Sasikumar P, Stanley RG, Simmonds AD, Bicknell AB, Gibbins JM. The platelet-surface thiol isomerase enzyme erp57 modulates platelet function. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essex DW. The role of thiols and disulfides in platelet function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:736–746. doi: 10.1089/1523086041361622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen VM, Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Berndt MC, Ruf W, Hogg PJ. Evidence for activation of tissue factor by an allosteric disulfide bond. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12020–12028. doi: 10.1021/bi061271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bach RR, Monroe D. What is wrong with the allosteric disulfide bond hypothesis? Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2009;29:1997–1998. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Li W, Ren J, Fang J, Ke H, Gong W, Feng W, Wang CC. Structural insights into the redox-regulated dynamic conformations of human protein disulfide isomerase. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jessop CE, Chakravarthi S, Garbi N, Hammerling GJ, Lovell S, Bulleid NJ. Erp57 is essential for efficient folding of glycoproteins sharing common structural domains. The EMBO journal. 2007;26:28–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyles MM, Gilbert HF. Catalysis of the oxidative folding of ribonuclease a by protein disulfide isomerase: Pre-steady-state kinetics and the utilization of the oxidizing equivalents of the isomerase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:619–625. doi: 10.1021/bi00217a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munro S, Pelham HR. A c-terminal signal prevents secretion of luminal er proteins. Cell. 1987;48:899–907. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takemoto H, Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Miyata Y, Yahara I, Inoue K, Tashiro Y. Heavy chain binding protein (bip/grp78) and endoplasmin are exported from the endoplasmic reticulum in rat exocrine pancreatic cells, similar to protein disulfide-isomerase. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1992;296:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90554-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryser HJ, Levy EM, Mandel R, DiSciullo GJ. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus infection by agents that interfere with thiol-disulfide interchange upon virus-receptor interaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:4559–4563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallina A, Hanley TM, Mandel R, Trahey M, Broder CC, Viglianti GA, Ryser HJ. Inhibitors of protein-disulfide isomerase prevent cleavage of disulfide bonds in receptor-bound glycoprotein 120 and prevent hiv-1 entry. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:50579–50588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryser HJ, Mandel R, Ghani F. Cell surface sulfhydryls are required for the cytotoxicity of diphtheria toxin but not of ricin in chinese hamster ovary cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:18439–18442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conant CG, Stephens RS. Chlamydia attachment to mammalian cells requires protein disulfide isomerase. Cellular microbiology. 2007;9:222–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos CX, Stolf BS, Takemoto PV, Amanso AM, Lopes LR, Souza EB, Goto H, Laurindo FR. Protein disulfide isomerase (pdi) associates with nadph oxidase and is required for phagocytosis of leishmania chagasi promastigotes by macrophages. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2009;86:989–998. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0608354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellerman DA, Myles DG, Primakoff P. A role for sperm surface protein disulfide isomerase activity in gamete fusion: Evidence for the participation of erp57. Developmental cell. 2006;10:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshimori T, Semba T, Takemoto H, Akagi S, Yamamoto A, Tashiro Y. Protein disulfide-isomerase in rat exocrine pancreatic cells is exported from the endoplasmic reticulum despite possessing the retention signal. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:15984–15990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terada K, Manchikalapudi P, Noiva R, Jauregui HO, Stockert RJ, Schilsky ML. Secretion, surface localization, turnover, and steady state expression of protein disulfide isomerase in rat hepatocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:20410–20416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monnat J, Neuhaus EM, Pop MS, Ferrari DM, Kramer B, Soldati T. Identification of a novel saturable endoplasmic reticulum localization mechanism mediated by the c-terminus of a dictyostelium protein disulfide isomerase. Molecular biology of the cell. 2000;11:3469–3484. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson S, Michalak M, Opas M, Eggleton P. The ins and outs of calreticulin: From the er lumen to the extracellular space. Trends in cell biology. 2001;11:122–129. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01926-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riewald M, Kravchenko VV, Petrovan RJ, O'Brien PJ, Brass LF, Ulevitch RJ, Ruf W. Gene induction by coagulation factor xa is mediated by activation of protease-activated receptor 1. Blood. 2001;97:3109–3116. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson AE, van Waes MA. The translocon: A dynamic gateway at the er membrane. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:799–842. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turano C, Coppari S, Altieri F, Ferraro A. Proteins of the pdi family: Unpredicted non-er locations and functions. Journal of cellular physiology. 2002;193:154–163. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan SW, Lin CF, Lu YT, Lei HY, Anderson R, Lin YS. Endothelial cell surface expression of protein disulfide isomerase activates beta1 and beta3 integrins and facilitates dengue virus infection. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2012;113:1681–1691. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pulvirenti T, Giannotta M, Capestrano M, Capitani M, Pisanu A, Polishchuk RS, San Pietro E, Beznoussenko GV, Mironov AA, Turacchio G, Hsu VW, Sallese M, Luini A. A traffic-activated golgi-based signalling circuit coordinates the secretory pathway. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:912–922. doi: 10.1038/ncb1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capitani M, Sallese M. The kdel receptor: New functions for an old protein. FEBS letters. 2009;583:3863–3871. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blair P, Flaumenhaft R. Platelet alpha-granules: Basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood reviews. 2009;23:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thon JN, Peters CG, Machlus KR, Aslam R, Rowley J, Macleod H, Devine MT, Fuchs TA, Weyrich AS, Semple JW, Flaumenhaft R, Italiano JE., Jr. T granules in human platelets function in tlr9 organization and signaling. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;198:561–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerrard JM, White JG, Peterson DA. The platelet dense tubular system: Its relationship to prostaglandin synthesis and calcium flux. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 1978;40:224–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ko MK, Kay EP. Subcellular localization of procollagen i and prolyl 4-hydroxylase in corneal endothelial cells. Experimental cell research. 2001;264:363–371. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Nispen Tot Pannerden HE, van Dijk SM, Du V, Heijnen HF. Platelet protein disulfide isomerase is localized in the dense tubular system and does not become surface expressed after activation. Blood. 2009;114:4738–4740. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hotchkiss KA, Matthias LJ, Hogg PJ. Exposure of the cryptic arg-gly-asp sequence in thrombospondin-1 by protein disulfide isomerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1388:478–488. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lame MW, Jones AD, Wilson DW, Segall HJ. Monocrotaline pyrrole targets proteins with and without cysteine residues in the cytosol and membranes of human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:4398–4413. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramachandran N, Root P, Jiang XM, Hogg PJ, Mutus B. Mechanism of transfer of no from extracellular s-nitrosothiols into the cytosol by cell-surface protein disulfide isomerase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:9539–9544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171180998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang LM, St Croix C, Cao R, Wasserloos K, Watkins SC, Stevens T, Li S, Tyurin V, Kagan VE, Pitt BR. Cell-surface protein disulfide isomerase is required for transnitrosation of metallothionein by s-nitroso-albumin in intact rat pulmonary vascular endothelial cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1507–1515. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swiatkowska M, Szymanski J, Padula G, Cierniewski CS. Interaction and functional association of protein disulfide isomerase with alphavbeta3 integrin on endothelial cells. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:1813–1823. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho J, Kennedy DR, Lin L, Huang M, Merrill-Skoloff G, Furie BC, Furie B. Protein disulfide isomerase capture during thrombus formation in vivo depends on the presence of beta3 integrins. Blood. 2012;120:9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lahav J, Jurk K, Hess O, Barnes MJ, Farndale RW, Luboshitz J, Kehrel BE. Sustained integrin ligation involves extracellular free sulfhydryls and enzymatically catalyzed disulfide exchange. Blood. 2002;100:2472–2478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim K, Hahm E, Li J, Holbrook LM, Sasikumar P, Stanley RG, Ushio-Fukai M, Gibbins JM, Cho J. Platelet protein disulfide isomerase is required for thrombus formation but not for hemostasis in mice. Blood. 2013;122:1052–1061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-492504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lam SC, Plow EF, D'Souza SE, Cheresh DA, Frelinger AL, 3rd, Ginsberg MH. Isolation and characterization of a platelet membrane protein related to the vitronectin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3742–3749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lawler J, Hynes RO. An integrin receptor on normal and thrombasthenic platelets that binds thrombospondin. Blood. 1989;74:2022–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan B, Smith JW. A redox site involved in integrin activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:39964–39972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manickam N, Ahmad SS, Essex DW. Vicinal thiols are required for activation of the alphaiibbeta3 platelet integrin. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1207–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lahav J, Wijnen EM, Hess O, Hamaia SW, Griffiths D, Makris M, Knight CG, Essex DW, Farndale RW. Enzymatically catalyzed disulfide exchange is required for platelet adhesion to collagen via integrin alpha2beta1. Blood. 2003;102:2085–2092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mor-Cohen R, Rosenberg N, Landau M, Lahav J, Seligsohn U. Specific cysteines in beta3 are involved in disulfide bond exchange-dependent and -independent activation of alphaiibbeta3. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:19235–19244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mor-Cohen R, Rosenberg N, Einav Y, Zelzion E, Landau M, Mansour W, Averbukh Y, Seligsohn U. Unique disulfide bonds in epidermal growth factor (egf) domains of beta3 affect structure and function of alphaiibbeta3 and alphavbeta3 integrins in different manner. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:8879–8891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz C, Liu CY, Sun QH, Sigaud-Fiks M, Fressinaud E, Muller JY, Nurden P, Nurden AT, Newman PJ, Valentin N. A point mutation in the cysteine-rich domain of glycoprotein (gp) iiia results in the expression of a gpiib-iiia (alphaiibbeta3) integrin receptor locked in a high-affinity state and a glanzmann thrombasthenia-like phenotype. Blood. 2001;98:2432–2441. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Neill S, Robinson A, Deering A, Ryan M, Fitzgerald DJ, Moran N. The platelet integrin alpha iibbeta 3 has an endogenous thiol isomerase activity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:36984–36990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye F, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. Reconstruction of integrin activation. Blood. 2012;119:26–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-292128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vandendries ER, Hamilton JR, Coughlin SR, Furie B, Furie BC. Par4 is required for platelet thrombus propagation but not fibrin generation in a mouse model of thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:288–292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610188104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodgers RP, Levin J. A critical reappraisal of the bleeding time. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 1990;16:1–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hrachovinova II, Cambien B, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Kappelmayer J, Camphausen RT, Widom A, Xia L, Kazazian HH, Schaub RG, McEver RP, Wagner DD. Interaction of p-selectin and psgl-1 generates microparticles that correct hemostasis in a mouse model of hemophilia a. Nat Med. 2003;9:1020–1025. doi: 10.1038/nm899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bellido-Martin L, Furie BC, Flaumenhaft R, Zwicker J, Furie B. Inhibitors of extracellular protein disulfide isomerase as antithrombotics in a mouse pulmonary embolism model. 2014 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walker KW, Lyles MM, Gilbert HF. Catalysis of oxidative protein folding by mutants of protein disulfide isomerase with a single active-site cysteine. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1972–1980. doi: 10.1021/bi952157n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwertassek U, Weingarten L, Dick TP. Identification of redox-active cell-surface proteins by mechanism-based kinetic trapping. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:pl8. doi: 10.1126/stke.4172007pl8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Appenzeller-Herzog C, Ellgaard L. The human pdi family: Versatility packed into a single fold. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1783:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stopa J, Furie BC, Furie B. Inhibition of protein disulfide isomerase prevents activation of platelet factor v. 2014 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jeimy SB, Fuller N, Tasneem S, Segers K, Stafford AR, Weitz JI, Camire RM, Nicolaes GA, Hayward CP. Multimerin 1 binds factor v and activated factor v with high affinity and inhibits thrombin generation. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2008;100:1058–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zai A, Rudd MA, Scribner AW, Loscalzo J. Cell-surface protein disulfide isomerase catalyzes transnitrosation and regulates intracellular transfer of nitric oxide. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1999;103:393–399. doi: 10.1172/JCI4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sliskovic I, Raturi A, Mutus B. Characterization of the s-denitrosation activity of protein disulfide isomerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:8733–8741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laurindo FR, Fernandes DC, Amanso AM, Lopes LR, Santos CX. Novel role of protein disulfide isomerase in the regulation of nadph oxidase activity: Pathophysiological implications in vascular diseases. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2008;10:1101–1113. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, Masliah E, Nomura Y, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylated protein-disulphide isomerase links protein misfolding to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;441:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Benham AM. The protein disulfide isomerase family: Key players in health and disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2012;16:781–789. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang B, Li FA, Wu CH, Wang DL. The role of nitric oxide on rosuvastatin-mediated s-nitrosylation and translational proteomes in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Proteome Sci. 2012;10:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang B, Chen SC, Wang DL. Shear flow increases s-nitrosylation of proteins in endothelial cells. Cardiovascular research. 2009;83:536–546. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen SC, Huang B, Liu YC, Shyu KG, Lin PY, Wang DL. Acute hypoxia enhances proteins’ s-nitrosylation in endothelial cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;377:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stamler JS, Jaraki O, Osborne J, Simon DI, Keaney J, Vita J, Singel D, Valeri CR, Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide circulates in mammalian plasma primarily as an s-nitroso adduct of serum albumin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:7674–7677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bell SE, Shah CM, Gordge MP. Protein disulfide-isomerase mediates delivery of nitric oxide redox derivatives into platelets. The Biochemical journal. 2007;403:283–288. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shah CM, Bell SE, Locke IC, Chowdrey HS, Gordge MP. Interactions between cell surface protein disulphide isomerase and s-nitrosoglutathione during nitric oxide delivery. Nitric Oxide. 2007;16:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ignarro LJ. Biological actions and properties of endothelium-derived nitric oxide formed and released from artery and vein. Circulation research. 1989;65:1–21. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Current vascular pharmacology. 2012;10:4–18. doi: 10.2174/157016112798829760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Radomski MW, Palmer RM, Moncada S. An l-arginine/nitric oxide pathway present in human platelets regulates aggregation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:5193–5197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chiang TM, Woo-Rasberry V, Cole F. Role of platelet endothelial form of nitric oxide synthase in collagen-platelet interaction: Regulation by phosphorylation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1592:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bruckdorfer R. The basics about nitric oxide. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2005;26:3–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loscalzo J. Nitric oxide insufficiency, platelet activation, and arterial thrombosis. Circulation research. 2001;88:756–762. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Root P, Sliskovic I, Mutus B. Platelet cell-surface protein disulphide-isomerase mediated s-nitrosoglutathione consumption. The Biochemical journal. 2004;382:575–580. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seno T, Inoue N, Gao D, Okuda M, Sumi Y, Matsui K, Yamada S, Hirata KI, Kawashima S, Tawa R, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Sakurai H, Yokoyama M. Involvement of nadh/nadph oxidase in human platelet ros production. Thrombosis research. 2001;103:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(01)00341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moldovan L, Mythreye K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Satterwhite LL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular endothelial cell motility. Roles of nad(p)h oxidase and rac1. Cardiovascular research. 2006;71:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gorlach A, Brandes RP, Nguyen K, Amidi M, Dehghani F, Busse R. A gp91phox containing nadph oxidase selectively expressed in endothelial cells is a major source of oxygen radical generation in the arterial wall. Circulation research. 2000;87:26–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Janiszewski M, Lopes LR, Carmo AO, Pedro MA, Brandes RP, Santos CX, Laurindo FR. Regulation of nad(p)h oxidase by associated protein disulfide isomerase in vascular smooth muscle cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:40813–40819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fernandes DC, Manoel AH, Wosniak J, Jr., Laurindo FR. Protein disulfide isomerase overexpression in vascular smooth muscle cells induces spontaneous preemptive nadph oxidase activation and nox1 mrna expression: Effects of nitrosothiol exposure. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2009;484:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.de APAM, Verissimo-Filho S, Guimaraes LL, Silva AC, Takiuti JT, Santos CX, Janiszewski M, Laurindo FR, Lopes LR. Protein disulfide isomerase redox-dependent association with p47(phox): Evidence for an organizer role in leukocyte nadph oxidase activation. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2011;90:799–810. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0610324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kyrle PA, Minar E, Bialonczyk C, Hirschl M, Weltermann A, Eichinger S. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men and women. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:2558–2563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nagarakanti R, Sodhi S, Lee R, Ezekowitz M. Chronic antithrombotic therapy in post-myocardial infarction patients. Cardiol Clin. 2008;26:277–288, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jasuja R, Passam FH, Kennedy DR, Kim SH, van Hessem L, Lin L, Bowley SR, Joshi SS, Dilks JR, Furie B, Furie BC, Flaumenhaft R. Protein disulfide isomerase inhibitors constitute a new class of antithrombotic agents. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2104–2113. doi: 10.1172/JCI61228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu S, Sankar S, Neamati N. Protein disulfide isomerase: A promising target for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khan MM, Simizu S, Lai NS, Kawatani M, Shimizu T, Osada H. Discovery of a small molecule pdi inhibitor that inhibits reduction of hiv-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:245–251. doi: 10.1021/cb100387r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bi S, Hong PW, Lee B, Baum LG. Galectin-9 binding to cell surface protein disulfide isomerase regulates the redox environment to enhance t-cell migration and hiv entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:10650–10655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017954108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoffstrom BG, Kaplan A, Letso R, Schmid RS, Turmel GJ, Lo DC, Stockwell BR. Inhibitors of protein disulfide isomerase suppress apoptosis induced by misfolded proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:900–906. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ge J, Zhang CJ, Li L, Chong LM, Wu X, Hao P, Sze SK, Yao SQ. Small molecule probe suitable for in situ profiling and inhibition of protein disulfide isomerase. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2577–2585. doi: 10.1021/cb4002602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banerjee R, Pace NJ, Brown DR, Weerapana E. 1,3,5-triazine as a modular scaffold for covalent inhibitors with streamlined target identification. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:2497–2500. doi: 10.1021/ja400427e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]