Abstract

We report a patient with pregnancy related obstructive sleep apnea ([OSA]; apnea hypopnea index [AHI] 18/h) early after delivery, with improvement of AHI by 87% following 45-degree elevation in body position compared with the non-elevated position. Improvement associated with this position may be explained, at least in part, by an increased upper airway diameter (as measured during wakefulness). Sleep apnea in this patient resolved at 9 months postpartum. This observation suggests that 45-degree elevated body position may be an effective treatment of pregnancy related OSA during the postpartum period.

Citation:

Jung S, Zaremba S, Heisig A, Eikermann M. Elevated body position early after delivery increased airway size during wakefulness, and decreased apnea hypopnea index in a woman with pregnancy related sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(7):815-817.

Keywords: pregnancy, polysomnography, sleep apnea, positional therapy, post-partum

Hormonal changes during pregnancy cause water retention leading to increased upper airway (UA) resistance and pregnancy related obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The incidence of sleep apnea is high and associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Depending on method used for assessment and population studied, symptoms of sleep apnea occurred in up to 85% in a cohort of women with preeclampsia.1–3 During the postpartum period, airway obstructions are a main cause of anesthesia related maternal death in North America,4 and increased vulnerability to airway obstruction may be successfully treated with adequate body position, as elevated posture has been shown to improve UA size accessed by acoustic pharyngometry5 and collapsibility during anesthesia6 and sleep, as well as during wakefulness in pregnant women.7,8 Nevertheless, the effect of elevated upper body position on airway size and pregnancy associated OSA is currently unknown. We evaluated the effects of elevated upper body position on nocturnal breathing in a woman during her second night after delivery.

REPORT OF CASE

A 43-year-old woman was admitted to the labor floor at term for induction of labor. The patient's medical history was unremarkable except for a previous diagnosis of endometriosis and a smoking history. HELLP syndrome, preeclampsia, eclampsia, anemia, or gestational diabetes mellitus had not been diagnosed during her pregnancy, and blood glucose level was 85 mg/dL prior to delivery. The sleep focused interview revealed typical OSA symptoms, which had started during late pregnancy: severe snoring, frequent nocturnal awakening due to her own snoring or with choking sensation, and severe daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 16/24).

Her body mass index (BMI) was 35.2 kg/m2 prior to pregnancy and 40.1 kg/m2 at time of vaginal delivery. The patient had an uncomplicated 20-h induction of labor including epidural analgesia and delivery of a male infant with Apgar scores of 7 and 9.

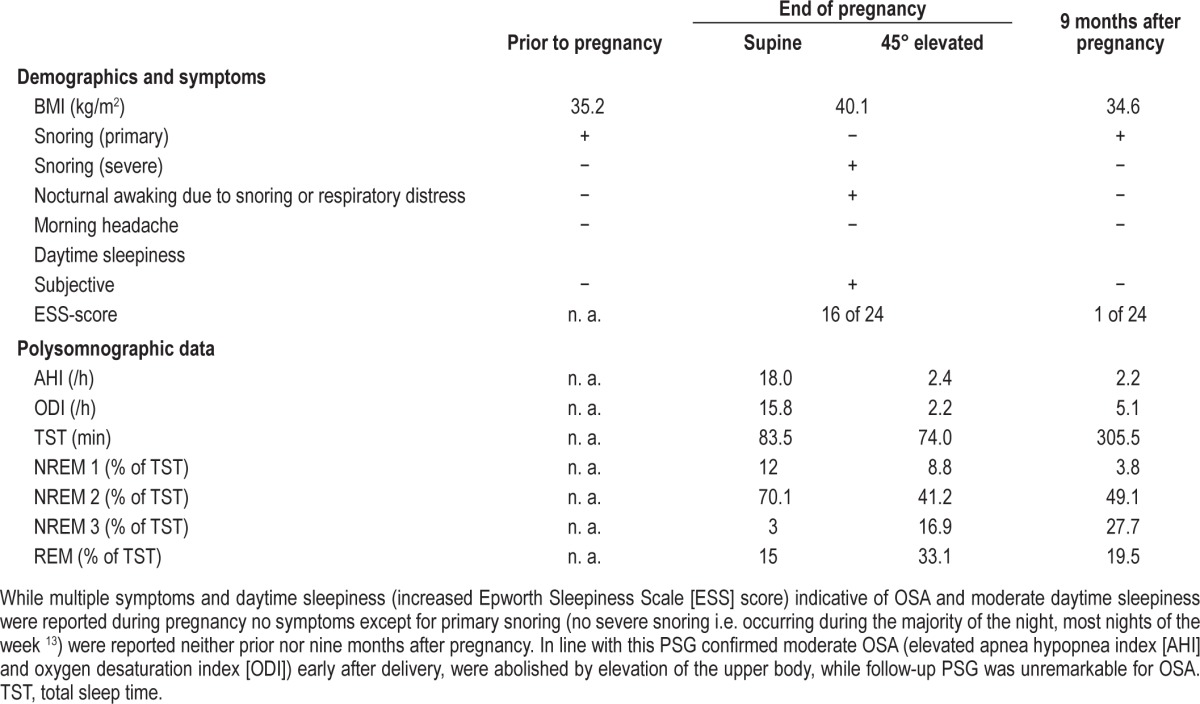

As part of an ongoing institutional review board approved research protocol, whole night polysomnography (PSG) was performed during the second night after delivery on the post-partum floor (22:30 to 04:00) using an out-of-center PSG monitoring device (Alice PDx, Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA) during sleep in non-elevated and 45-degree elevated body position (3 h each). Apnea hypopnea index (AHI) in the non-elevated body position averaged 18.0/h and decreased to normal levels (AHI of 2.4/h) following transition to 45-degree elevation. At the same time, sleep architecture was improved (i.e., percentage of total sleep time spent in NREM and REM sleep) to values similar to those seen during the follow-up PSG performed 9 months after delivery at the patient's home (Table 1).

Table 1.

Obstructive sleep apnea OSA symptoms and BMI data for the time prior to, at the end of, and nine months after pregnancy, as well as PSG data during non-elevated and 45-degree elevated body posture early after delivery and at 9 months follow-up

The following morning, we evaluated the effects of changes in upper body position on airway anatomy using acoustical pharyngometry (Eccovision Acoustic Pharyngometry, Sleep Group Solutions, Miami, FL).5,7 UA diameter during wakefulness increased from non-elevated (supine) to sitting (0.43 cm2 in supine body position to 0.46 cm2 at 45 degrees elevation and 0.49 cm2 during sitting body posture). We speculate that the increase in UA diameter from non-elevated to the elevated back position may explain some of the improvement in UA patency during sleep.

A PSG follow-up study conducted 9 months after delivery showed primary snoring without signs of sleep disordered breathing in this patient (AHI 2.2/h), while she reported full resolution of her symptoms of OSA during the first months postpartum (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Three main factors which promote OSA during pregnancy are higher extraluminal pressure generated by structures surrounding the pharyngeal airway, increased negative airway pressure generated by respiratory pump muscles due to a higher ventilatory drive, and smaller end-expiratory lung volume due to increased abdominal volume during pregnancy.1,9 We here present a noninvasive, low-technology treatment alternative for pregnancy-related OSA during the early post-partum period: elevated body position. The underlying mechanism may include beneficial effects on pharyngeal tissue edema and rostral fluid shift similar to those observed in patients with heart failure10 and an increase in functional residual capacity and endexpiratory lung volume.9 Thus elevated body posture may be an effective, inexpensive, and easy treatment for pregnancy-related OSA and should be the subject of further investigation. Our report emphasizes the effects of elevated body position on sleep disordered breathing after delivery. It is important to mention that our results do not have direct implications on OSA in pregnancy, where the supine position with elevated upper body may affect uterine perfusion and cardiac output.11

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Eikermann has received research funding from ResMed Foundation, Merck and Massimo. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourjeily G, Ankner G, Mohsenin V. Sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O' Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Pregancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: prospective cohort study. Am J Ostet Gynecol. 2012;207:487.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izci B, Martin SE, Dundas KC, Liston WA, Calder AA, Douglas NJ. Sleep complaints: snoring and daytime sleepiness in pregnant and pre-eclamptic women. Sleep Med. 2005;6:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mhyre JM, Riesner MN, Polley LS, Naughton NN. A series of anesthesia-related maternal deaths in Michigan, 1985-2003. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1096–104. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267592.34626.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouke JM, Strohl KP. Effect of position and lung volume on upper airway geometry. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:375–80. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagaito Y, Isono S, Tanaka A, Ishikawa T, Nishino T. Sitting posture decreases collapsibility of the passive pharynx in anesthetized paralyzed patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:812–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f1b834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izci B, Rhina RL, Martin SE, et al. The upper airway in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:137–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-590OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izci B, Vennelle M, Liston WA, Dundas KC, Calder AA, Douglas NJ. Sleep-disordered breathing and upper airway size in preganancy and post-partum. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:321–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00148204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014;383:736–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White LH, Bradley TD. Role of nocturnal rostral fluid shift in the pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnoea. J Physiol. 2013;591:1179–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.245159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon MC. Maternal Physiology. In: Gabbe SG, editor. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. New York: Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myers KA, Mrkobrada M, Simel DL. Does this patient have obstructive sleep apnea?: The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA. 2013;310:731–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]