Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common form of muscular dystrophy caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. Loss of dystrophin initiates a progressive decline in skeletal muscle integrity and contractile capacity which weakens respiratory muscles including the diaphragm, culminating in respiratory failure, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DMD patients. At present, corticosteroid treatment is the primary pharmacological intervention in DMD, but has limited efficacy and adverse side effects. Thus, there is an urgent need for new safe, cost-effective, and rapidly implementable treatments that slow disease progression. One promising new approach is the amplification of nitric oxide–cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO–cGMP) signalling pathways with phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors. PDE5 inhibitors serve to amplify NO signalling that is attenuated in many neuromuscular diseases including DMD. We report here that a 14-week treatment of the mdx mouse model of DMD with the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil (Viagra®, Revatio®) significantly reduced mdx diaphragm muscle weakness without impacting fatigue resistance. In addition to enhancing respiratory muscle contractility, sildenafil also promoted normal extracellular matrix organization. PDE5 inhibition slowed the establishment of mdx diaphragm fibrosis and reduced matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) expression. Sildenafil also normalized the expression of the pro-fibrotic (and pro-inflammatory) cytokine tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα). Sildenafil-treated mdx diaphragms accumulated significantly less Evans Blue tracer dye than untreated controls, which is also indicative of improved diaphragm muscle health. We conclude that sildenafil-mediated PDE5 inhibition significantly reduces diaphragm respiratory muscle dysfunction and pathology in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. This study provides new insights into the therapeutic utility of targeting defects in NO–cGMP signalling with PDE5 inhibitors in dystrophin-deficient muscle.

Keywords: dystrophin, mdx, nitric oxide, cGMP, sildenafil, PDE5, fibrosis, TNFα, MMP-13, diaphragm

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a common neuromuscular disease caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene [1]. DMD patients exhibit progressive skeletal muscle degeneration and weakness as well as cardiomyopathy [2]. Dystrophin-deficient muscle exhibits chronic inflammation and over time, muscle cells are steadily replaced with fibrotic and fatty tissue [3–5]. Progressive endomysial fibrosis, the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix proteins collagen I and fibronectin around muscle cells, impairs normal muscle contractility, vascularization, and regeneration [2,5–7]. Fibrosis exacerbates both skeletal and cardiac muscle dysfunction and presents an important target for therapeutic intervention. Progressive respiratory muscle (diaphragm and intercostal) weakness leads to respiratory failure, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DMD patients. Cardiac failure, resulting from either cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias, is the second major cause of mortality in DMD [2].

Currently, corticosteroids constitute the primary treatment option for muscle dysfunction in DMD, but they exhibit limited efficacy, with serious side effects. The need for new treatments has led to a focus on pharmacological enhancement of nitric oxide–cyclic guanosine monophosphate (NO–cGMP) signalling pathways in dystrophic animals. NO is indispensable for muscle integrity and function. In skeletal muscle, NO is synthesized by neuronal nitric oxide synthase mu and beta (nNOSμ and nNOSβ), and regulates vascular function, muscle mass, fatigue resistance, atrophy, and fibre type [8–14]. Loss of dystrophin in both DMD patients and the mdx mouse model of DMD reduces nNOSμ expression and prevents its normal localization, thereby inhibiting the vasoregulatory role of nNOSμ and causing vascular dysfunction [8,13,15–18]. In active muscle, disruption of contraction-coupled nNOSμ signalling to the vasculature impairs muscle perfusion, causing ischaemic muscle damage and exaggerated inactivity after mild exercise [8,19,20]. Genetic enhancement of nNOS expression attenuates skeletal muscle inflammation and necrosis, improves exercise performance, and reduces cardiac fibrosis and contractile dysfunction in mdx mice [21–23]. These studies provide a strong rationale for determining the therapeutic utility of agents that amplify NO signalling in dystrophin-deficient muscle.

A major function of nNOS-derived NO is to stimulate cGMP production. This can be mimicked with phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra®/Revatio®) and tadalafil (Cialis®). These FDA-approved vasodilators are used to treat erectile dysfunction (considered an early clinical sign and risk factor of cardiovascular disease), pulmonary hypertension, and heart failure [24]. Low (pico-nanomolar) concentrations of NO bind and activate the ‘NO receptor’ soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), which amplifies the NO signal by synthesizing μM levels of cGMP. Downstream targets of cGMP include protein kinase G, cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels, and cGMP-activated PDEs [25,26]. PDE5 degrades cytosolic cGMP, thereby attenuating NO signalling intensity. Thus, inhibiting PDE5 can raise cytosolic cGMP levels and indirectly amplify NO signalling.

We and others have used PDE5 inhibitors to amplify NO signalling in mdx mice, leading to a clinical trial to test the impact of PDE5 inhibition on DMD-associated cardiomyopathy [27] (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01168908). Sildenafil enhanced sarcolemmal integrity and rapidly reversed left ventricle dysfunction in mdx hearts [27,28]. Tadalafil decreased contraction-induced ischaemic damage in mdx muscle [19]. Acute administration of sildenafil enhanced mdx mouse activity after moderate exercise by a nNOSμ-dependent mechanism [20]. While acute application of sildenafil shows promise as a therapeutic approach to dystrophy, the impact of chronic administration of sildenafil on skeletal muscle remains unknown. In the present study, we show that chronic sildenafil treatment improves respiratory muscle pathology and function.

Materials and methods

Animal models

All experimental procedures performed on mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington. Dystrophin-deficient C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/J (mdx) mice and C57BL/10ScSn/J strain controls were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All comparisons were made between age-matched male mice.

Sildenafil administration

The PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil citrate (Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) was administered in the drinking water ad libitum (400 mg/l) to wild-type and mdx mice (up to 5 per cage) for 14 weeks from 3 weeks of age. Using this approach, the average concentration of circulating sildenafil was 70 ± 0.05 nM over a 24-h period [27].

Diaphragm muscle contractile function

Diaphragm strength (specific force) and fatigue resistance were determined from 2–3 mm wide diaphragm strips. Strips were continually perfused with buffer (121 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, and 5.5 mM glucose) and bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4) at room temperature. A length–force curve was then determined by tetanic contractions (120 Hz, 300 ms duration), spaced 1 min apart to determine Lo, the length at which maximum tetanic force is generated. Muscle fibre length (Lf) at Lo is measured for calculation of specific force (maximal tetanic force output normalized to muscle cross-sectional area). Diaphragm strips were then subjected to a fatigue protocol involving repetitive stimulation at 1 Hz for 45 s. Force recovery was measured at 1-min intervals up to 10 min.

Evans Blue dye exclusion and serum creatine kinase activity assays

Evans Blue dye (EBD), a membrane-impermeant tracer dye, is a commonly used marker of skeletal muscle membrane permeability and integrity. A 10 mg/ml stock solution of EBD was prepared in PBS. A single dose (0.25 μg EBD per g of body weight) was administered by intraperitoneal injection. Mice were sacrificed 18 h later and whole diaphragms were dissected, mounted, and imaged. EBD levels were quantified using IMAGE J software V1.44P. Serum creatine kinase activity was determined as described previously [12].

Western immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, histology and the degeneration/regeneration index assay, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays

These methods are described in the Supplementary methods.

Statistics

Numbers of male mice analysed are provided in the figure legends. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction for unequal variance were used for pairwise comparisons of specific force output. Unpaired t-tests were also used for analyses of fold changes in qPCR arrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A repeat measures ANOVA was used to analyse force deficits during fatigue experiments, using time and treatment as variables. In all other experiments, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were used to determine significant differences between groups. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Sildenafil increases mdx diaphragm strength, but has no impact on fatigue resistance

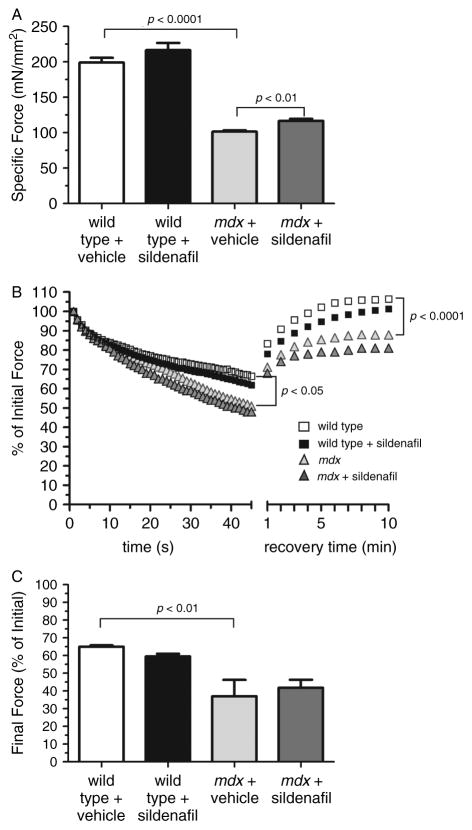

Respiratory failure, originating primarily from diaphragm weakness, is the major cause of mortality in DMD. We tested whether 14 weeks of sildenafil treatment could increase mdx diaphragm muscle strength. The mdx diaphragm is particularly informative because it exhibits the most severe dystrophic phenotype including excessive weakness, fatigability, and fibrosis observed in DMD patients [29,30]. Sildenafil did not affect wild-type diaphragm specific force, a measure of intrinsic muscle strength (Figure 1A). As expected, mdx diaphragms generated only ~50% (p < 0.0001) of the force of wild-type diaphragms (Figure 1A). However, sildenafil-treated mdx diaphragms exhibited a significant increase in specific force and were ~15% stronger (p < 0.01) than control mdx diaphragms (Figure 1A). By comparison, sildenafil is more effective than conventional steroid therapy, which does not improve mdx diaphragm specific force [31,32]. Thus, a 15 % improvement is very important in the context of mdx muscle function and compares very favourably with existing steroid therapy. Also, it is useful to compare the average specific force deficit between age-matched wild-type and mdx hindlimb muscles, which ranges from 20% to 25% (Supplementary Figure 1A) [33,34]. Steroids increase mdx hindlimb muscle specific force by about 26 %, whereas sildenafil did not significantly impact mdx tibialis anterior hindlimb strength (Supplementary Figure 1A) [35]. Thus, the impact of sildenafil on strength appears muscle-specific. These data suggest that sildenafil provides a significant enhancement of dystrophin-deficient diaphragm muscle strength.

Figure 1.

Sildenafil increases mdx diaphragm muscle specific force output. (A) Maximal specific force output of wild-type and mdx diaphragm strips treated with vehicle or sildenafil. Treated mdx mice were significantly stronger than untreated mdx controls. (B) Representative traces of fatigue resistance profiles of wild-type and mdx diaphragms treated with vehicle or sildenafil. Mdx muscles exhibited significant muscle fatigue compared with wild-type controls, with force deficits during repetitive stimulation and recovery phases (marked post-exercise weakness). Sildenafil treatment did not impact the fatigue resistance of wild-type or mdx diaphragm muscle. p < 0.05 refers to the difference in force output of untreated wild-type and untreated mdx diaphragms during repetitive stimulation. p < 0.0001 refers to the difference in force output of untreated wild-type and untreated mdx diaphragms during the recovery phase. (C) Mean final force output at the end of the repetitive stimulation phase in wild-type and mdx diaphragm strips treated with vehicle or sildenafil of a fatigue protocol. Mdx muscles show a significant force deficit at the end of repetitive stimulation compared with wild-type. Sildenafil has no impact on the final force output in wild-type or mdx diaphragms. Wild-type untreated and sildenafil-treated: n = 5 each. mdx untreated and sildenafil-treated: n = 5 and 9, respectively.

To further understand the impact of sildenafil on diaphragm contractility, we investigated its impact on diaphragm fatigue. Given that nNOS pathways promote muscle fatigue resistance and exercise capacity in both normal and mdx mice, we hypothesized that sildenafil would increase fatigue resistance in mdx mice [11,12,20,23,36]. Sildenafil had no impact on wild-type diaphragm fatigue (Figure 1B). As expected, mdx diaphragms were significantly less fatigue-resistant than controls (Figure 1B). Exaggerated mdx diaphragm fatigue was characterized by significant force deficits during both repetitive stimulation (p < 0.05) and recovery phases (p < 0.0001) compared with wild-type controls (Figures 1B and 1C). During the fatigue protocol, sildenafil had no impact on the decline of normalized force generation during the repetitive stimulation phase or on the marked post-exercise weakness of the recovery phase in either wild-type or mdx muscle (Figure 1B). On average, mdx muscle final force output levelled out at 37% of the initial force compared with 65% for wild type controls, demonstrating excessive muscle fatigue (Figure 1C). Final force output in either wild-type or mdx muscle was not significantly affected by sildenafil treatment. Collectively, these findings suggest that sildenafil did not affect mdx diaphragm fatigue resistance.

Sildenafil exhibits an anti-fibrotic activity in the mdx diaphragm

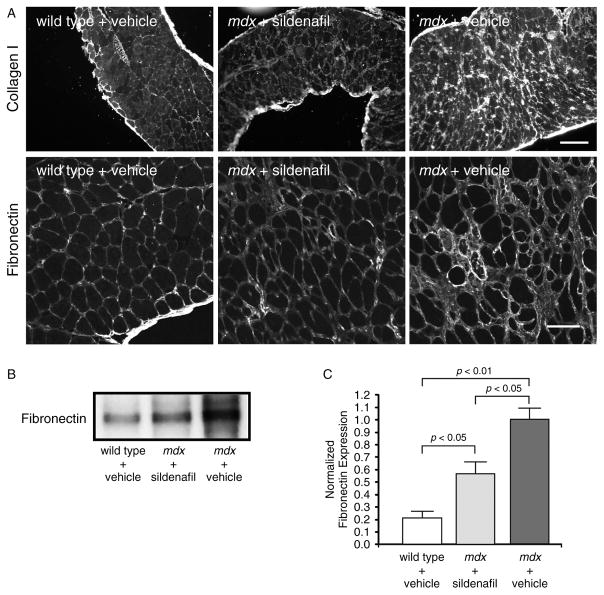

We investigated potential mechanisms for the sildenafil-mediated improvement in respiratory muscle strength and focused initially on fibrosis, which is thought to contribute to muscle weakness [6,7]. We examined two markers of fibrosis, collagen I and fibronectin, in dystrophin-deficient diaphragm (Figure 2A [6]). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that collagen I and fibronectin are expressed at low levels around muscle fibres in normal diaphragm, but are found at much higher amounts in mdx muscle as expected (Figure 2A). Importantly, both collagen I and fibronectin were markedly decreased by sildenafil treatment (Figure 2A). To provide a quantitative measure of the anti-fibrotic activity of sildenafil, fibronectin levels in diaphragm muscles were measured by western immunoblotting (Figures 2B and 2C). Fibronectin protein expression was five-fold higher (p < 0.01) in vehicle-treated mdx mice than in wild-type controls (Figures 2B and 2C). In agreement with immunohistochemical findings, an approximately 40% reduction (p < 0.05) in fibronectin expression was observed in sildenafil-treated mdx diaphragms compared with mdx controls (Figures 2B and 2C). These data suggested an important role for sildenafil in slowing the development of fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Sildenafil reduces endomysial fibrosis in the mdx diaphragm. (A) Representative diaphragm sections stained with collagen I (top row) and fibronectin (bottom row) antibodies. Both collagen I and fibronectin are markers of fibrosis in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Sildenafil reduced both collagen I and fibronectin deposition around mdx diaphragm muscle fibres. (B) Representative western blot of global fibronectin protein expression in vehicle and sildenafil-treated mdx diaphragms. Mdx diaphragms exhibit high levels of fibronectin that are significantly decreased by sildenafil treatment. (C) Western blot quantitation of fibronectin protein levels. Sildenafil significantly reduced fibronectin expression in the mdx diaphragm. Scale bars in A: 100 μm (top row) and 50 μm (bottom row). Wild-type (n = 5); vehicle and sildenafil-treated mdx mice (n = 4 each).

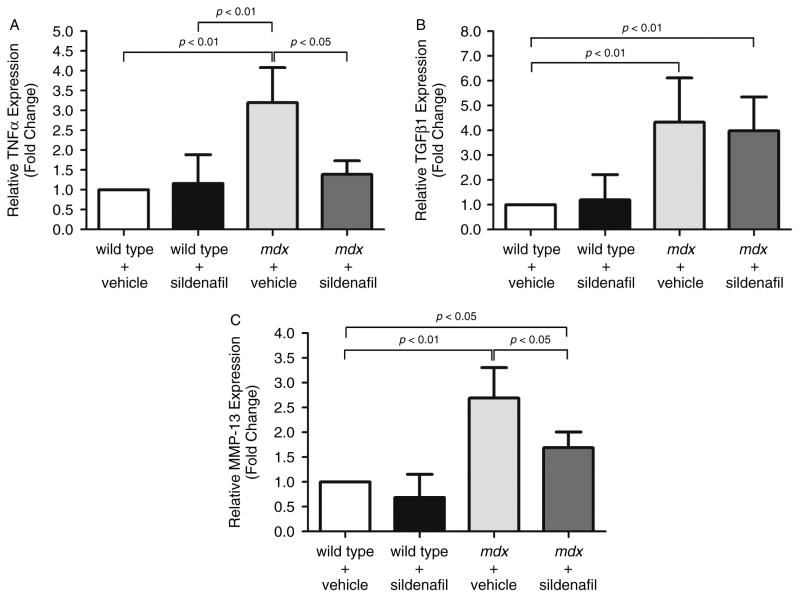

To further understand the anti-fibrotic properties of sildenafil, we investigated the impact of sildenafil on the expression of TNFα and TGFβ1, known to promote fibrosis in mdx muscle [37]. TNFα transcript expression was three-fold higher in mdx diaphragms compared with controls. This increase is consistent with previous reports in DMD patients and mdx mice (Figure 3A [38–40]). Sildenafil-mediated PDE5 inhibition significantly (p < 0.05) reduced mdx diaphragm TNFα expression to levels indistinguishable from wild-type controls (Figure 3A). These data suggest that reductions in TNFα could contribute to decreased fibrosis and increased diaphragm muscle strength.

Figure 3.

Chronic sildenafil treatment normalizes TNFα and decreases MMP-13 expression, but does not impact TGFβ1 in mdx diaphragms. The impact of sildenafil on regulators of inflammation (TNFα) and fibrosis (TNFα, MMP-13, TGFβ1) was evaluated at the transcript level by quantitative PCR. (A) TNFα expression was elevated 3.2-fold in mdx diaphragm tissue, but normalized to wild-type levels by sildenafil treatment. (B) Profibrotic TGFβ1 transcript expression was substantially elevated in mdx diaphragms 5.8-fold, but unaffected by sildenafil treatment. (C) MMP-13 expression was increased 2.7-fold in mdx diaphragm and was also significantly reduced by sildenafil. Wild-type vehicle- (n = 5), wild-type sildenafil- (n = 3), mdx vehicle- (n = 6), and sildenafil-treated mdx mice (n = 9).

The pro-fibrotic activity of TNFα in mdx mice may result from its ability to increase TGFβ1 expression, since TNFα blockade can reduce TGFβ1 and collagen I expression to wild-type levels [41]. To investigate the possibility that TNFα normalization reduced TGFβ1, thereby reducing fibrosis, we measured TGFβ1 expression. As expected, TGFβ1 expression was increased more than four-fold (p < 0.01) in vehicle-treated mdx diaphragm compared with either treated or untreated wild-type controls (Figure 3B). But sildenafil did not impact TGFβ1 expression in mdx diaphragms (Figure 3B). These data suggest that the regulation of TGFβ1 transcript expression by TNFα in dystrophic muscle may not be as tightly coupled as previously thought. It should be noted that these data do not diminish the importance of TGFβ1 in dystrophic muscle fibrosis or preclude an impact of sildenafil on TGFβ1 signalling that may occur independently of TGFβ1 transcript expression changes.

One additional line of evidence also supported the idea that sildenafil may work by opposing aberrant extracellular matrix (ECM) organization. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) expression is positively regulated by TNFα and may play a role in fibrosis [42]. MMP-13 expression was more than 2.5-fold higher (p < 0.01) in vehicle-treated mdx muscle than in wild-type controls (Figure 3C). As predicted, MMP-13 expression was also significantly decreased (p < 0.05) by sildenafil in mdx diaphragms relative to controls (Figure 3C). Thus, normalization of TNFα could account for decreased MMP-13 expression. These data suggest that MMP-13 may contribute to aberrant ECM organization in mdx muscle and highlight a previously unappreciated link between NO–cGMP signalling and matrix metalloproteinase pathways. To the best of our knowledge, MMP-13 has not been previously implicated in dystrophic pathology. Together, these data strongly suggest that sildenafil can significantly reduce fibrotic deposition in dystrophic diaphragm and may do so, at least in part, by acting through TNFα- and MMP-13.

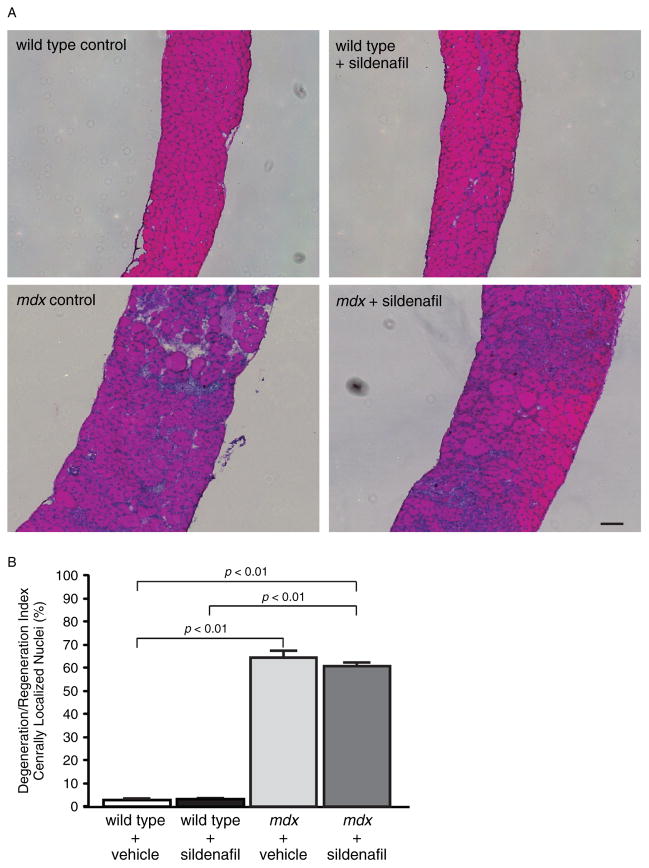

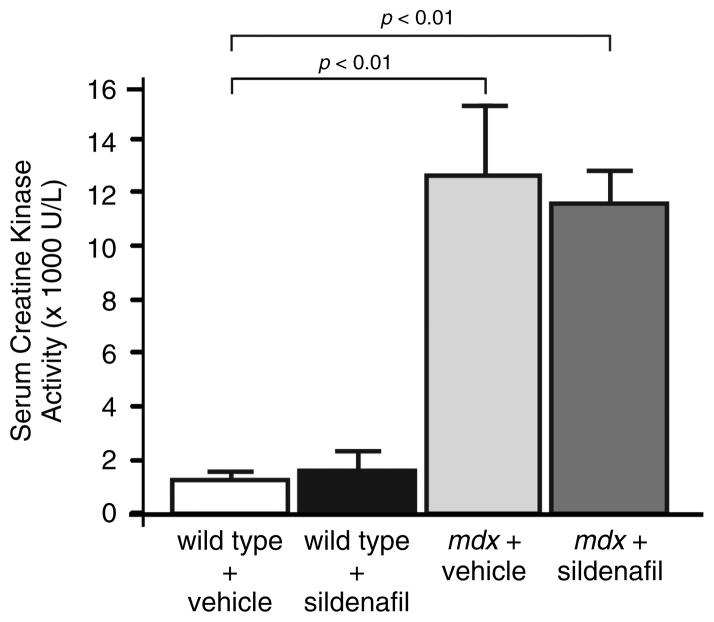

In addition to fibrosis, mdx diaphragm myofibres exhibit characteristically high levels of central nucleation that reflect substantial muscle breakdown and regeneration (Figures 4A and 4B) [29]. The fraction of muscle cells with centrally localized nuclei is a widely used measure of muscle degeneration and regeneration. About 60% (p < 0.01) of mdx diaphragm muscle cells are centrally nucleated compared with ~4% in wild-type controls (Figures 4A and 4B). Central nucleation was unaffected by sildenafil treatment in both wild-type and mdx muscle (Figures 4A and 4B). Similarly, sildenafil also did not affect central nucleation frequency in mdx tibialis anterior hindlimb muscles (Supplementary Figures 2A and 2B). Muscle degeneration or damage can also lead to elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) activity or hyperCKaemia. In dystrophic muscle, sustained hyperCKaemia is a diagnostic biomarker and is also thought to represent ongoing muscle damage. As expected, circulating CK levels were significantly elevated in mdx mice compared with controls, but were unaffected by sildenafil-mediated PDE5 inhibition (Figure 5). These findings are consistent with previous reports that circulating CK activity in normal or mdx adult mice is unaffected by changes in nNOS signalling [12,21,23]. Thus, the strength-enhancing and anti-fibrotic benefits of sildenafil were independent of a change in the balance of degeneration to regeneration or serum CK activity.

Figure 4.

Chronic sildenafil treatment did not impact central nucleation in the mdx diaphragm. (A) Representative images of haematoxylin and eosin-stained diaphragm muscle sections from vehicle- and sildenafil-treated wild-type (top row) and mdx (bottom row) mice. Mdx diaphragms revealed no overt differences in inflammatory cell infiltration or muscle necrosis. (B) Quantitation of the fraction of muscle fibres with centrally localized nuclei or degeneration/regeneration index. The fraction of centrally nucleated muscle cells was over 60% in mdx diaphragms compared with wild-type controls. Sildenafil treatment did not impact the degeneration/regeneration index. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 4 for each group, with all four diaphragms from each group haematoxylin and eosin-stained and analysed for central nucleation.

Figure 5.

Global serum creatine kinase activity is unaffected by sildenafil treatment. Elevated serum CK (hyperCKaemia) is typically used as a marker of muscle damage. Both vehicle- and sildenafil-treated wild-type animals show characteristically low CK activity. mdx mice exhibited characteristic hyperCKaemia, marked by high levels of serum activity that were unaffected by sildenafil treatment. n = 3 and 4 for vehicle- and sildenafil-treated wild-type mice, respectively. n = 4 and 5 for vehicle- and sildenafil-treated mdx mice, respectively.

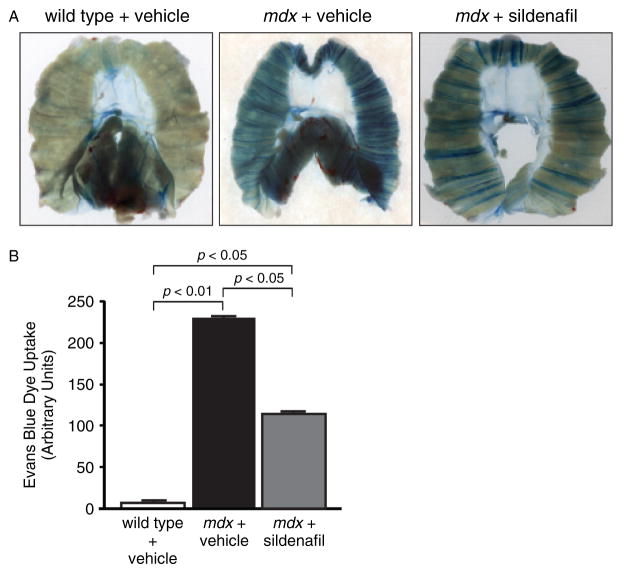

Sildenafil reduces extracellular dye accumulation in mdx diaphragms

Another key pathological characteristic of dystrophin-deficient muscle is its increased permeability to extracellular tracer dyes, such as Evans Blue dye (EBD). Increased dye exclusion ability correlates well with reductions in fibrosis and improved muscle health [43,44]. Therefore, based on the attenuation of fibrosis, we hypothesized that sildenafil-treated mdx diaphragm muscles would also exhibit improved dye exclusion (Figure 6). Vehicle-treated wild-type diaphragm muscles were largely impermeable to EBD (Figure 6A). In contrast, untreated mdx diaphragms exhibited pronounced EBD accumulation (Figure 6A). Importantly, sildenafil significantly reduced mdx diaphragm permeability to EBD (Figure 6A). Quantification of EBD accumulation revealed a 40% reduction (p < 0.01) in EBD uptake in mdx diaphragms compared with mdx controls (Figure 6B). These data suggest that sildenafil can also improve dystrophic muscle health by attenuating membrane permeability. The EBD exclusion assay results correlate well with decreased contractile dysfunction and fibrosis and indicate that sildenafil significantly improved both mdx diaphragm integrity and function.

Figure 6.

Sildenafil reduces sarcolemmal and vascular permeability of mdx diaphragm muscle tissue. (A) Whole mounts of diaphragm respiratory muscles showing extensive accumulation of Evans Blue dye (EBD) in mdx diaphragms which was reduced by sildenafil treatment. (B) Quantification of EBD uptake. Sildenafil significantly reduces EBD uptake by the mdx diaphragm. EBD uptake studies were performed in four mice for each group and representative images are shown.

Discussion

Despite major advances in non-invasive ventilatory support, respiratory failure stemming from skeletal muscle weakness remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DMD. To address this pathology, new, safe, efficacious, and cost-effective therapies are required. The major finding of the present study is that chronic sildenafil treatment significantly reduced diaphragm respiratory muscle weakness and fibrosis in the mdx mouse model of DMD. This study provides compelling new support for the therapeutic utility of targeting defective NO–cGMP signalling in dystrophin-deficient muscle with PDE5 inhibitors.

The first finding was the novel demonstration that chronic amplification of NO signalling by sildenafil enhanced mdx diaphragm strength by 15%. This increase appears modest only until it is compared with existing steroid therapy for DMD, which does not affect dystrophin-deficient diaphragm specific force and improves mdx hindlimb muscle strength by ~26% [31,32,35]. Furthermore, from a clinical point of view, if this sildenafil-mediated improvement in diaphragm strength were to translate from mouse to human, this would still constitute a significant advance in therapy and a very important addition to existing clinical treatment options for respiratory dysfunction, particularly for older DMD patients. Surprisingly, given that nNOS enzymes promote fatigue resistance, sildenafil did not impact mdx diaphragm muscle fatigue, suggesting that the cGMP pool regulated by PDE5 does not play a role in diaphragm fatigue.

These findings raise the question as to how sildenafil increases mdx diaphragm strength. Although the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated, this study implicates several pathways that may act separately or in concert to improve mdx muscle strength. First, sildenafil may enhance strength by improving diaphragm tissue perfusion. Indeed, given the vasoregulatory role of nNOSμ and that sildenafil is a potent vasodilator, improved diaphragm tissue perfusion may contribute to increased strength by reducing ischaemic damage [8,17–19]. However, neither restored nNOSμ vasoregulatory activity nor acute sildenafil-mediated muscle perfusion increases mdx hindlimb skeletal muscle strength [20,23]. These studies suggest that sildenafil’s vasodilatory activity has little or no effect on mdx diaphragm strength and certainly none on fatigue. However, other factors may be at play here that influence sildenafil’s impact including muscle-specific differences (Supplementary Figure 1A) as well as the duration of drug treatment. Thus, mechanisms other than vasodilation per se appear responsible for the impact of prolonged PDE5 inhibition on mdx diaphragm contractility.

One likely contributing mechanism to the sildenafil-mediated increase in mdx diaphragm strength is the substantial reduction of fibrosis. In DMD patients, fibrosis may cause skeletal muscle weakness including diaphragm dysfunction, which in turn decreases chest wall compliance and increases work required for breathing [7]. Left ventricle fibrosis impairs wall movement and promotes ventricular arrhythmias in DMD patients [2]. Thus, fibrosis is an important pathogenic feature in muscular dystrophy [37]. In mdx mice, extensive diaphragm fibrosis occurs after the onset of diaphragm weakness; therefore, fibrosis does not cause early diaphragm weakness in young (~6 weeks old) mdx mice [45]. However, with time, there is a progressive decline in diaphragm specific force that parallels the development of fibrosis, which is similar to findings in DMD [7,46]. Thus, fibrosis likely contributes to muscle weakness in older mdx mice. In this study, sildenafil treatment markedly reduced deposition of collagen I and fibronectin in the mdx diaphragm (Figure 2A). As expected, the attenuation of fibrosis was associated with enhanced diaphragm contractility in sildenafil-treated 17-week-old mdx mice. These data are consistent with the findings that tadalafil can qualitatively reduce diaphragm fibrosis and that NO can oppose cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in mdx mice [19,22]. Taken together, this body of work provides compelling evidence that NO–cGMP pathways oppose fibrosis in dystrophin-deficient muscle. These data support the clinical relevance of fibrosis to dystrophic muscle dysfunction and the potential therapeutic utility of targeting fibrotic pathways with sildenafil.

What are the mechanisms by which sildenafil reduces diaphragm fibrosis? Since sildenafil (inhibits PDE5 and PDE1c) and tadalafil (inhibits PDE5 and PDE11) both decrease fibrosis, we conclude that PDE5 inhibition is responsible for attenuating mdx diaphragm fibrosis [19]. Furthermore, sildenafil normalized TNFα cytokine expression, suggesting a plausible downstream target of increased cGMP (Figure 3A). Excessive TNFα signalling causes inflammation, fibrosis, muscle catabolism, and vascular dysfunction, as well as skeletal (diaphragm) and cardiac muscle weakness [47–51]. TNFα is elevated in DMD patients and in mdx mice (increasing = 4 weeks of age) and may promote fibrosis and muscle weakness (Figure 3A [29,38–41]). Indeed, TNFα causes muscle necrosis, fibrosis, weakness, and respiratory dysfunction in adult mdx mice [40,52–54]. These studies provide compelling evidence that the sildenafil-mediated normalization of TNFα expression could lead to a reduction in mdx diaphragm fibrosis and contractile dysfunction. In summary, our current working model is that sildenafil-mediated TNFα normalization directly increases diaphragm strength in two ways: (1) by alleviating the force-depressing activity of TNFα, particularly in younger mdx mice; and (2) by indirectly enhancing diaphragm contractility in older mdx mice by inhibiting the pro-fibrotic activity of TNFα.

The anti-fibrotic action of sildenafil may also result from an impact on MMP-13 (Figure 3C). TNFα positively regulates the expression of MMP-13, a collagenase that regulates extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and can promote fibrosis [42,55,56]. Importantly, MMP-13 may have a role in skeletal muscle regeneration and repair [57]. MMP-13 levels were significantly elevated in the mdx diaphragm, consistent with the profibrotic extracellular environment (Figure 3C). Sildenafil also reduced MMP-13 transcript levels, which is consistent with TNFα as a positive regulator of MMP-13, although it is also possible that reductions in MMP-13 expression occur independently of TNFα (Figure 3C). Interestingly, MMP-13 is also a key activator of MMP-9, whose excessive activity can worsen mdx pathology [55,58]. So, decreasing MMP-13 may result in a beneficial reduction in MMP-9. Further studies are required to determine how changes in TNFα and MMP-13 message levels correlate with protein expression and activity. These data suggest that the anti-fibrotic impact of PDE5 inhibition in mdx diaphragm could result from the normalization of TNFα, which may in turn attenuate the expression of pathogenic MMPs including MMP-13 and possibly MMP-9, thereby promoting a more normal ECM.

Sildenafil-mediated reductions in fibrosis and weakness correlated well with decreased Evans Blue dye (EBD) accumulation in mdx diaphragms, consistent with improved muscle integrity (Figure 6). This is consistent with reduced EBD uptake in muscles of 4-week-old mdx mice treated with tadalafil in utero [19]. Sarcolemmal microtears are thought to be one mechanism by which EBD enters muscle cells; however, other mechanisms have been proposed [59]. Thus, the conventional interpretation for reduced EBD uptake is that sildenafil-treated mdx mice have less muscle damage or microtears. In this case, we would also expect a reduction in both hyperCKaemia and central nucleation; however, both of these pathological indices were unaffected by sildenafil. An absence of impact of sildenafil on central nucleation may reflect the timing of drug administration. Central nucleation reflects the balance of muscle degeneration to regeneration and increases rapidly during the first weeks of life in mdx muscle before plateauing. Administration of sildenafil to 3-week-old mdx mice simply may have been too late to impact the degree of central nucleation. Another possibility is that sildenafil may have simultaneously decreased degeneration (reflected in decreased diaphragm muscle fibrosis and increased muscle strength) and improved regeneration, leaving total levels of central nucleation apparently unchanged. Further studies are required to address these possibilities. These data suggest that muscle EBD accumulation (or influx) and creatine kinase efflux across the sarcolemma are distinct processes with unique sensitivities to NO–cGMP signalling. These data are consistent with recent reports of reductions in fibrosis and EBD accumulation that occurred independently of changes in hyperCKaemia in mdx mice [43,44]. Alternatively, persistent global hyperCKaemia may be explained by sildenafil improving mdx diaphragm integrity only, without affecting the integrity of other skeletal muscles. This possibility is consistent with the observation that sildenafil preferentially improves the function of respiratory, but not hindlimb, skeletal muscle. Collectively, these findings support a tight linkage between EBD exclusion and fibrosis in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Furthermore, mitigation of mdx dystrophic pathology resulting from either TNFα depletion or increased NO concentrations can also occur independently of changes in serum CK activity [21,23,60]. From a therapeutic perspective, reductions in global serum CK activity and central nucleation were clearly unnecessary for the sildenafil-mediated reduction in fibrosis, diaphragm muscle weakness, and cardiomyopathy [27]. In studies targeting defective NO signalling in muscular dystrophy, caution must be exercised to prevent overreliance on central nucleation and hyperCKaemia as a measure of therapeutic impact.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that chronic sildenafil treatment significantly reduces respiratory muscle weakness and fibrosis. These findings suggest a novel application of PDE5 inhibitors to the treatment of respiratory muscle dysfunction in DMD. Therapeutic approaches that address secondary pathology in DMD will ideally slow the progression of both respiratory dysfunction and cardiomyopathy. Such approaches should also be safe, cost-effective, useful in combination with existing corticosteroid treatments, and easily implementable. These therapies can potentially buy time and improve quality of life until more comprehensive treatments directed at the primary gene defect become available. We previously demonstrated that sildenafil reduces cardiomyopathy in mdx mice and thus appears to meet the requirements of a therapeutic agent targeting secondary pathology. Therefore, sildenafil shows promise as an adjunct therapeutic for dystrophic disease. Importantly, these findings may be broadly applicable to other neuromuscular diseases that lack normal NO signalling pathway function [20].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Kimberley Craven for critical editing of the manuscript. This research was supported by NIH grants NS33145 (SCF), NS59514 (SCF and JAB), and AR056221 (SCF and JAB), and by a Muscular Dystrophy Association Development Grant (JMP), a Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy Investigator Award (SCF), the Weisman Fellowship from Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (NPW), and Charlie’s Fund (SCF and JAB).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Author contribution statement

All authors made substantial contributions to experimental design and analysis and interpretation of data. JMP, NPW, MEA, and CA acquired data. All listed coauthors were involved in drafting the manuscript and approving the final version to be published.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION ON THE INTERNET

The following supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Figure S1. Chronic sildenafil has no significant impact on mdx tibialis anterior muscle strength.

Figure S2. Chronic sildenafil treatment did not impact the numbers of central nucleated muscle cells in the mdx tibialis anterior hindlimb muscle.

References

- 1.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology. 2003;99:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000068446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YW, Nagaraju K, Bakay M, et al. Early onset of inflammation and later involvement of TGFβ in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2005;65:826–834. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173836.09176.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tidball JG, Wehling-Henricks M. Damage and inflammation in muscular dystrophy: potential implications and relationships with autoimmune myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:707–713. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000179948.65895.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernasconi P, Torchiana E, Confalonieri P, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in dystrophic patient muscles correlates with fibrosis. Pathogenetic role of a fibrogenic cytokine. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1137–1144. doi: 10.1172/JCI118101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hantaï D, Labat-Robert J, Grimaud JA, et al. Fibronectin, laminin, type I, III and IV collagens in Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, congenital muscular dystrophies and congenital myopathies: an immunocytochemical study. Connect Tissue Res. 1985;13:273–281. doi: 10.3109/03008208509152408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desguerre I, Mayer M, Leturcq F, et al. Endomysial fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a marker of poor outcome associated with macrophage alternative activation. Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:762–773. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181aa31c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas GD, Sander M, Lau KS, et al. Impaired metabolic modulation of alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15090–15095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas GD, Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, et al. Vasomodulation by skeletal muscle-derived nitric oxide requires alpha-syntrophin-mediated sarcolemmal localization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res. 2003;92:554–560. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000061570.83105.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki N, Motohashi N, Uezumi A, et al. NO production results in suspension-induced muscle atrophy through dislocation of neuronal NOS. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2468–2476. doi: 10.1172/JCI30654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Percival JM, Anderson KN, Gregorevic P, et al. Functional deficits in nNOSmu-deficient skeletal muscle: myopathy in nNOS knockout mice. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Percival JM, Anderson KN, Huang P, et al. Golgi and sarcolemmal neuronal NOS differentially regulate contraction-induced fatigue and vasoconstriction in exercising mouse skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:816–826. doi: 10.1172/JCI40736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Percival JM, Adamo CM, Beavo JA, et al. Evaluation of the therapeutic utility of phosphodiesterase 5A inhibition in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011;204:323–344. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17969-3_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Percival JM. nNOS regulation of skeletal muscle fatigue and exercise performance. Biophys Rev. 2011;3:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s12551-011-0060-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenman JE, Chao DS, Xia H, et al. Nitric oxide synthase complexed with dystrophin and absent from skeletal muscle sarcolemma in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1995;82:743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang WJ, Iannaccone ST, Lau KS, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase and dystrophin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9142–9147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito K, Kimura S, Ozasa S, et al. Smooth muscle-specific dystrophin expression improves aberrant vasoregulation in mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2266–2275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato K, Yokota T, Ichioka S, et al. Vasodilation of intramuscular arterioles under shear stress in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle is impaired through decreased nNOS expression. Acta Myol. 2008;27:30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asai A, Sahani N, Kaneki M, et al. Primary role of functional ischemia, quantitative evidence for the two-hit mechanism, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy in mouse muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2007;2:e806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi YM, Rader EP, Crawford RW, et al. Sarcolemma-localized nNOS is required to maintain activity after mild exercise. Nature. 2008;456:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature07414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wehling M, Spencer MJ, Tidball JG. A nitric oxide synthase transgene ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:123–131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wehling-Henricks M, Jordan MC, Roos KP, et al. Cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient hearts is prevented by expression of a neuronal nitric oxide synthase transgene in the myocardium. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai Y, Thomas GD, Yue Y, et al. Dystrophins carrying spectrin-like repeats 16 and 17 anchor nNOS to the sarcolemma and enhance exercise performance in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:624–635. doi: 10.1172/JCI36612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cvelich RG, Roberts SC, Brown JN. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors as adjunctive therapy in the management of systolic heart failure. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:1551–1558. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmann F, Feil R, Kleppisch T, et al. Function of cGMP-dependent protein kinases as revealed by gene deletion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1–23. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craven KB, Zagotta WN. CNG and HCN channels: two peas, one pod. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:375–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.134728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamo CM, Dai DF, Percival JM, et al. Sildenafil reverses cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19079–19083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013077107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khairallah M, Khairallah RJ, Young ME, et al. Sildenafil and cardiomyocyte-specific cGMP signaling prevent cardiomyopathic changes associated with dystrophin deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7028–7033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710595105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stedman HH, Sweeney HL, Shrager JB, et al. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991;352:536–539. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregorevic P, Plant DR, Leeding KS, et al. Improved contractile function of the mdx dystrophic mouse diaphragm muscle after insulin-like growth factor-I administration. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2263–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64502-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L, Luo J, Petrof BJ. Corticosteroid therapy does not alter the threshold for contraction-induced injury in dystrophic (mdx ) mouse diaphragm. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:394–397. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199803)21:3<394::aid-mus14>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinkle RT, Lefever FR, Dolan ET, et al. Corticortophin releasing factor 2 receptor agonist treatment significantly slows disease progression in mdx mice. BMC Med. 2007;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellorusso C, Crawford RW, Chamberlain JS, et al. Tibialis anterior muscles in mdx mice are highly susceptible to contraction-induced injury. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2001;22:467–475. doi: 10.1023/a:1014587918367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch GS, Hinkle RT, Faulkner JA. Power output of fast and slow skeletal muscles of mdx (dystrophic) and control mice after clenbuterol treatment. Exp Physiol. 2000;85:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baltgalvis KA, Call JA, Nikas JB, et al. Effects of prednisolone on skeletal muscle contractility in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:443–454. doi: 10.1002/mus.21327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wehling-Henricks M, Oltmann M, Rinaldi C, et al. Loss of positive allosteric interactions between neuronal nitric oxide synthase and phosphofructokinase contributes to defects in glycolysis and increased fatigability in muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3439–3451. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou L, Lu H. Targeting fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:771–776. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181e9a34b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porreca E, Guglielmi MD, Uncini A, et al. Haemostatic abnormalities, cardiac involvement and serum tumor necrosis factor levels in X-linked dystrophic patients. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:543–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saito K, Kobayashi D, Komatsu M, et al. A sensitive assay of tumor necrosis factor alpha in sera from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Clin Chem. 2000;46:1703–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang P, Zhao XS, Fields M, et al. Imatinib attenuates skeletal muscle dystrophy in mdx mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:2539–2548. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gosselin LE, Martinez DA. Impact of TNF-alpha blockade on TGF-beta1 and type I collagen mRNA expression in dystrophic muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:244–246. doi: 10.1002/mus.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borden P, Solymar D, Sucharczuk A, et al. Cytokine control of interstitial collagenase and collagenase-3 gene expression in human chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23577–23581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohn RD, van Erp C, Habashi JP, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-beta-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nature Med. 2007;13:204–210. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heydemann A, Ceco E, Lim JE, et al. Latent TGF-beta-binding protein 4 modifies muscular dystrophy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3703–3712. doi: 10.1172/JCI39845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coirault C, Pignol B, Cooper RN, et al. Severe muscle dysfunction precedes collagen tissue proliferation in mdx mouse diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1744–1750. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00989.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faulkner JA, Ng R, Davis CS, et al. Diaphragm muscle strip preparation for evaluation of gene therapies in mdx mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:725–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor, other cytokines and disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:317–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walley KR, Hebert PC, Wakai Y, et al. Decrease in left ventricular contractility after tumor necrosis factor-alpha infusion in dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1060–1067. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilcox PG, Wakai Y, Walley KR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha decreases in vivo diaphragm contractility in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1368–1373. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Moody MR, Engel D, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha causes oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction in mouse diaphragm. Circulation. 2000;102:1690–1696. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardin BJ, Campbell KS, Smith JD, et al. TNF-alpha acts via TNFR1 and muscle-derived oxidants to depress myofibrillar force in murine skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:694–699. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00898.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gosselin LE, Barkley JE, Spencer MJ, et al. Ventilatory dysfunction in mdx mice: impact of tumor necrosis factor-alpha deletion. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:336–343. doi: 10.1002/mus.10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grounds MD, Torrisi J. Anti-TNFalpha (Remicade) therapy protects dystrophic skeletal muscle from necrosis. FASEB J. 2004;18:676–682. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1024com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piers AT, Lavin T, Radley-Crabb HG, et al. Blockade of TNF in vivo using cV1q antibody reduces contractile dysfunction of skeletal muscle in response to eccentric exercise in dystrophic mdx and normal mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leeman MF, Curran S, Murray GI. The structure, regulation, and function of human matrix metalloproteinase-13. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:149–166. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uchinami H, Seki E, Brenner DA, et al. Loss of MMP 13 attenuates murine hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology. 2006;44:420–429. doi: 10.1002/hep.21268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu N, Jansen ED, Davidson JM. Comparison of mouse matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression in free-electron laser and scalpel incisions during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:926–932. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H, Mittal A, Makonchuk DY, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition ameliorates pathogenesis and improves skeletal muscle regeneration in muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2584–2598. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen DG, Whitehead NP. Duchenne muscular dystrophy—what causes the increased membrane permeability in skeletal muscle? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spencer MJ, Marino MW, Winckler WM. Altered pathological progression of diaphragm and quadriceps muscle in TNF-deficient, dystrophin-deficient mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:612–619. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.