Abstract

Objective

To identify correlates of risky sexual behavior among adolescents surviving childhood cancer.

Methods

The Child Health and Illness Profile - Adolescent Edition (CHIP-AE) was completed by 307 survivors of childhood cancer aged 15–20 years (M age at diagnosis 1.53 years; range 0–3.76). Univariate analyses were performed using Chi-square and Fischer’s exact tests, and multivariable logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals for risky sexual behaviors.

Results

Diagnosis of central nervous system cancer (OR =.13, 95% CI: .02–.96, p<.05), no history of beer/wine consumption (OR =.20, CI: .06–.68, p =.01), and fewer negative peer influences (OR =.28, CI: .09–.84, p =.02) associated with decreased likelihood of sexual intercourse. Good psychological health (scores ≥ −1.5 SD on the CHIP-AE Emotional Discomfort scale) associated with decreased risk of early intercourse (OR =.19, CI: .05–.77, p= .02), whereas high parental education (≥ college degree) associated with decreased risk of multiple lifetime sexual partners (OR =.25, CI: .09–.72, p =.01). Increased time from diagnosis (OR =.27, CI: .10–.78, p = .02) and psychological health (OR =.09, CI: .02–.36, p < .01) associated with decreased risk of unprotected sex at last intercourse, whereas high parent education associated with increased risk (OR = 4.27, CI: 1.46–12.52, p =.01).

Conclusions

Risky sexual behavior in adolescents surviving childhood cancer is associated with cancer type, time since diagnosis, psychological health, alcohol use, and peer influences. Consideration of these factors may provide direction for future interventions designed to reduce adolescent sexual risk-taking.

Keywords: risky sexual behavior, childhood cancer, survivors, adolescents

Adolescents commonly engage in risky health behaviors (e.g., tobacco, drug and alcohol use, unprotected sex), which are associated with a variety of adverse outcomes including substance abuse and dependence, academic and vocational underachievement, and poor physical and mental health (Nebbit et al., 2010; Park et al., 2010; Staton et al., 1999; Vaughn et al., 2009). As such, it is important to identify factors associated with risky behavior, particularly among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer, a population at high risk for late health-related complications (Bhatia et al., 2003; Hudson et al., 2003; Oeffinger et al., 2006). Engagement in risky behavior exacerbates health risk among survivors, resulting in vulnerabilities to both acute and chronic adverse health outcomes (Emmons, 2008; Emmons et al., 2002; Van Leeuwen et al., 1995). Thus, survivors of childhood cancer should abstain from or limit risky health behavior as a mechanism for remaining healthy.

One behavior receiving increased attention is risky sexual behavior, which is defined as the engagement of sexual behavior that increases one’s risk of negative health outcomes including transmission/contraction of infection or disease, or unintended pregnancy (CDC, 2013). Examples of risky sexual behavior include unprotected oral, vaginal, or anal contact/intercourse, early sexual debut, multiple sexual partners, and engagement in sexual encounters with high risk individuals. Genital human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection, has been identified as causing cervical and other HPV-related cancers (Sauvageau et al., 2007; Weinstock et al., 2004). HPV is transmitted skin-to-skin and is spread via genital/genital, oral/genital, or digital/genital contact. Infection rates are highest among sexually active adolescents and rise sharply soon after the median age of sexual debut (16 years; Wulf, 2002). The prevalence of HPV is 30–49% among sexually active males and females 14 to 25 years of age (Dunne et al., 2007; Guiliano et al., 2008), with a lifetime prevalence approaching 80% among those who are sexually active. Survivors of childhood cancer have significantly increased risks of developing subsequent HPV-associated malignancies in adulthood relative to their peers (150% excess risk for males, 40% for females overall), and these risks increase to 1200% for penile and 760% for tonsillar cancers among males and females previously treated with radiation therapy (Ojha et al., 2013). Treatment-related immunocompromise has been suggested as a potential mechanism explaining this increased risk (Barzon, Pizzighella, Corti, Mengoli, & Palu, 2002; Bhatia et al., 2001; Sasadeusz et al., 2001). Despite these potential consequences, adolescent survivors of childhood cancer continue to engage in risky sexual behavior at rates equivalent to their siblings (Klosky et al., 2012).

With these potential risks in mind, the current investigation utilized problem behavior theory (PBT; Jessor, 1993; Jessor, et al., 1995) as the theoretical framework for understanding risky sexual behavior in adolescent survivors. By recognizing the interplay between social (i.e., controls, models, and support), psychological (i.e., beliefs, attitudes, orientation), developmental (i.e., age-related norms and expectations, transition-marking behaviors), and environmental risk/protective factors, the consideration of PBT in the survivorship context may be particularly useful for understanding risky sexual behavior in this vulnerable group (Scaraella et al., 1998, Vazsonyi et al., 2008). For example, survivors may encounter unique life experiences such as an atypical developmental trajectory secondary to treatment, engagement in risky behavior as a mechanism for rejoining peer groups post treatment, and needing to balance cognitive dissonance and social desirablity when engaging in cancer-linked behaviors. All of these factors may associate with risky sexual behavior. Although testing the full PBT model is outside of the scope of this study, previous research has identified PBT-consistent factors such as peer influence, school performance, socioeconomic status, and psychological health as contributing to risky health behavior in survivors (Stolley et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2009; Krull et al., 2010). These relationships have not yet been examined in relation to sexual risk-taking among adolescent survivors, but it is hypothesized that these described factors also differentiate engagement in risky sexual behavior in this group as well. Finally, cancer-specific factors have also been associated with academic performance, quality of social interactions, and alcohol use (Dolson et al., 2009; Ris & Noll, 2000), factors that have also been linked to risky sexual behavior in adolescents without a history of cancer. Therefore, the influence of factors within and between social, enviromental, biological, developmental, and psychological domains may be magnifed by the biological vulnerability observed in survivors of childhood cancer and should be considered in this high risk population.

Despite their increased health risks secondary to cancer treatment, no current studies have considered factors contributing to risky sexual behavior among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. As such, the purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between potential risk/protective factors and sexual risk taking in this compromised group.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this Institutional Review Board-approved study were selected from the adolescent subset of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort, a cohort of childhood cancer survivors in the US and Canada (Robison et al., 2009). Details of the study and participant characteristics have been reported previously (Robison et al., 2002; Robison et al., 2009), and the prevalence of risky (including sexual) behaviors (and comparisons to sibling controls) have also been reported in the adolescent subset as well (Klosky et al., 2012). Briefly, the overall cohort includes individuals who were treated for leukemia, lymphoma, central nervous system (CNS) malignancy, kidney cancer, neuroblastoma, malignant bone tumor, or soft tissue sarcoma at 26 institutions in the US and Canada. To be eligible for the larger cohort, participants were diagnosed between 1970 and 1986, were less than 21 years of age at diagnosis, and had survived at least 5 years post diagnosis.

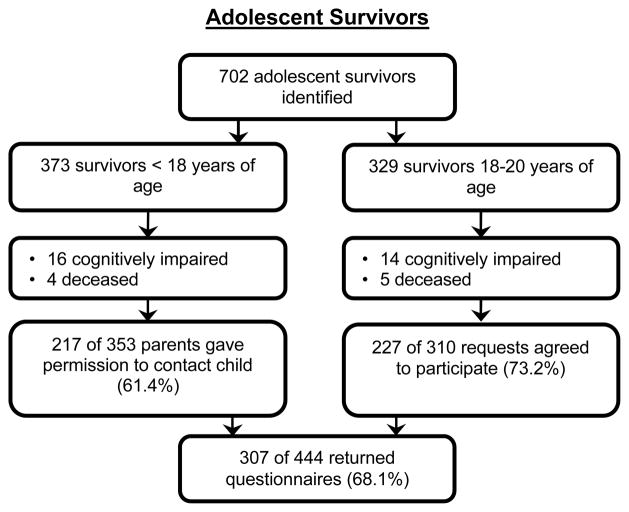

At the time of study recruitment, 702 survivors aged 15–19 years met preliminary eligibility for this study based on age. Because only the youngest in the original CCSS cohort were considered for participation in this study, all survivors were between 0 and 3.76 years of age at diagnosis. Furthermore, because some of the oldest adolescents returned the study questionnaire after turning 20 years of age, the age range of the participants will be reported as 15–20 years. With respect to demographic, diagnostic, and treatment characteristics, survivors who were White, older, female, and from households with an income of ≥ $60,000 were more likely to participate in the study as compared to non-participants (p-values ranged from < .01 – .03). Data collection was completed in 2005, and reasons for refusing participation or failing to return questionnaires were not collected. See Figure 1 for enrollment details.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting participant recruitment and questionnaire completion for adolescent survivors.

Instrumentation

Adolescent risk-taking behaviors and associated factors were assessed using the Child Health and Illness Profile - Adolescent Edition (CHIP-AE; Starfield et al., 1994). The CHIP-AE is a 214-item self-report measure that evaluates teen health status in six global domains: (1) Satisfaction, (2) Discomfort, (3) Resilience, (4) Risks, (5) Achievement, and (6) Disorders, and yields 20 subdomains. Items on the CHIP-AE are scored on a Likert-type scale, typically ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate healthier, or decreased, risk behavior. CHIP-AE subdomain scores are standardized at 20 with a standard deviation of 5. Those participants whose scores fell at or below −1.5 SD (e.g., scores falling at 12.5 or lower) were classified in “at risk” groups, whereas those with scores falling above −1.5 SD were considered to be in the “decreased risk” groups. The −1.5 SD boundary has traditionally been used when identifying disordered behavior/psychological functioning in adolescents, and utilization of this cutoff allows for comparison with other published research (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2004). Internal reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) for the CHIP-AE subdomains have previously been reported as ranging from .72 – .87 (Starfield et al., 1995), and with the exception of Psychosocial Disorders, ranged from .60 – .89 in the present study. See Starfield et al. 1995 and 1996 for detailed information regarding the validity and other psychometric properties of the CHIP-AE.

Primary Outcomes

Measurement of risky sexual behavior was also assessed as part of the CHIP-AE, and outcomes are defined as follows: 1) history of sexual intercourse (yes/no), 2) age in years at first intercourse (< or ≥ 16 years of age), 3) number of sexual partners (< or ≥ 2 partners), and 4) utilization of contraception/pregnancy prevention or sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention at last sexual intercourse (yes/no). Less than 16 years of age was used to describe “early” onset of sexual intercourse, as the median age for first sexual intercourse in the US is 16 years (Wulf, 2002). For the purposes of this study, the last item was separated into two distinct items addressing (a) pregnancy prevention and (b) STI prevention. Participants endorsing any of the hormonal or barrier contraceptive options (condom/rubber, birth control pill/Norplant/Depo Provera, diaphragm or sponge, or foam/jelly use) were coded as “yes” for pregnancy prevention, whereas only those who reported condom use were coded as “yes” for STI prevention. As a result, 5 risky sexual behaviors were utilized as primary outcomes in this study.

Independent Variables

Sociodemographic and Medical Variables

The following sociodemographic factors were obtained via self-report: gender (male/female), age in years (15–17/18–20), race (White/non-White), educational status (in school/not in school), and parent education (< college graduate/≥ college graduate). Medical factors that were considered included cancer diagnosis, time since diagnosis, treatment type, and history of CNS-directed treatment. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic, Medical, Behavioral and Psychological Characteristics by Risky Sexual Behavior of Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer

| History of Sexual Intercourse (N= 307) | Early Initiation of Sexual Intercourse (n= 110) | Multiple Sexual Partners (n= 110) | Pregnancy Prevention at Last Intercourse (n=110) | STI Prevention at Last Intercourse (n= 110) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fYes N (%) |

No N (%) |

Yes N (%) |

No N (%) |

Yes N (%) |

No N (%) |

Yes N (%) |

No N (%) |

Yes N (%) |

No N (%) |

|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 35 (28.5) | 88 (71.5)* | 9 (25.7) | 26 (74.3) | 18 (54.6) | 15 (45.4) | 28 (84.8) | 5 (15.2) | 28 (80.0) | 7 (20.0) |

| Female | 75 (41.2) | 107 (58.8) | 29 (38.7) | 46 (61.3) | 46 (61.3) | 29 (38.7) | 64 (85.3) | 11 (14.7) | 51 (68.0) | 24 (32.0) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Age in Years | ||||||||||

| 15–17 | 34 (26.8) | 93 (73.2)** | 18 (52.9) | 16 (47.1)** | 19 (55.9) | 15 (44.1) | 28 (82.4) | 6 (17.6) | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.5) |

| 18–20 | 76 (42.7) | 102 (57.3) | 20 (26.3) | 56 (73.7) | 45 (60.8) | 29 (39.2) | 64 (86.5) | 10 (13.5) | 53 (69.7) | 23 (30.3) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| White | 97 (35.9) | 173 (64.1) | 32 (33.0) | 65 (67.0) | 56 (57.7) | 41 (42.3) | 82 (84.5) | 15 (15.5) | 70 (72.2) | 27 (27.8) |

| Non-White | 13 (37.1) | 22 (62.9) | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.8) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Education Status | ||||||||||

| In School | 48 (27.3) | 128 (72.7)** | 20 (41.7) | 28 (58.3) | 27 (56.3) | 21 (43.7) | 42 (87.5) | 6 (12.5) | 38 (79.2) | 10 (20.8) |

| Not in School | 49 (55.7) | 39 (44.3) | 14 (28.6) | 35 (71.4) | 26 (55.3) | 21 (44.7) | 41 (87.2) | 6 (12.8) | 33 (67.3) | 16 (32.7) |

| Not indicated | 13 (31.7) | 28 (68.3) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Parent Education | ||||||||||

| < College graduate | 53 (43.1) | 70 (56.9)* | 19 (35.9) | 34 (64.1) | 37 (69.8) | 16 (30.2)* | 48(90.6) | 5 (9.4)+ | 43 (81.1) | 10 (18.9)* |

| ≥ College graduate | 54 (31.6) | 117 (68.4) | 17 (31.5) | 37 (68.5) | 26 (49.1) | 27 (50.9) | 42 (79.2) | 11 (20.8) | 34 (63.0) | 20 (37.0) |

| Don’t know | 3 (27.3) | 8 (72.7) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) | - | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Time since diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Median split low | 42 (27.8) | 109 (72.2)** | 18 (42.9) | 24 (57.1)+ | 21 (52.5) | 19 (47.5) | 32 (80.0) | 8 (20.0) | 26 (61.9) | 16 (38.1)+ |

| Median split high | 68 (44.2) | 86 (55.8) | 20 (29.4) | 48 (70.6) | 43 (63.2) | 25 (36.8) | 60 (88.2) | 8 (11.8) | 53 (77.9) | 15 (22.1) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Leukemia | 33 (34.7) | 62 (65.3)* | 12 (36.4) | 21 (63.6)+ | 24 (75.0) | 8 (25.0) | 28 (87.5) | 4 (12.5) | 23 (69.7) | 10 (30.3) |

| CNS | 9 (22.5) | 31 (77.5) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) |

| Neuroblastoma | 29 (33.0) | 59 (67.0) | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) | 16 (55.2) | 13 (44.8) | 26 (89.7) | 3 (10.3) | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) |

| Other | 39 (47.6) | 43 (52.4) | 8 (20.5) | 31 (79.5) | 19 (50.0) | 19 (50.0) | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) | 24 (61.5) | 15 (38.5) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Treatment Modalities | ||||||||||

| Surgery only | 17 (41.5) | 24 (58.5)+ | 6 (35.3) | 11 (64.7) | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) |

| Radiation therapy only | 2 (18.2) | 9 (81.8) | 2 (100) | - | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) | - | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Chemotherapy only | 58 (40.3) | 85 (59.0) | 20 (34.5) | 38 (65.5) | 34 (58.6) | 24 (41.4) | 52 (89.7) | 6 (10.3) | 44 (75.9) | 14 (24.1) |

| Chemotherapy + RT | 25 (25.5) | 73 (74.5) | 6 (24.0) | 19 (76.0) | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.7) | 18 (75.0) | 6 (25.0) | 15 (60.0) | 10 (40.0) |

| No treatment | - | 2 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unknown | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) |

|

| ||||||||||

| CNS Treatment | ||||||||||

| No CNS treatment | 77 (40.3) | 114 (59.7)+ | 24 (31.2) | 53 (68.8) | 40 (52.6) | 36 (47.4)* | 65 (85.5) | 11 (14.5) | 58 (75.3) | 19 (24.7) |

| Any CNS treatment | 33 (29.0) | 81 (71.0) | 14 (42.4) | 19 (57.6) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (25.0) | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cigarette Use | ||||||||||

| Current | 33 (73.3) | 12 (26.7)** | 16 (48.5) | 17 (51.5)+ | 28 (84.9) | 5 (15.1)** | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | 39 (72.2) | 15 (27.8) |

| Past | 26 (65.0) | 14 (35.0) | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.4) | 14 (53.9) | 12 (46.1) | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | 28 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) |

| Never | 51 (23.4) | 167 (76.6) | 13 (25.5) | 38 (74.5) | 22 (44.9) | 27 (55.1) | 43 (87.8) | 6 (12.2) | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| Unknown | - | 2 (100) | - | - | - | - | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | 39 (72.2) | 15 (27.8) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Beer/wine Use | ||||||||||

| Current | 54 (62.1) | 33 (37.9)** | 22 (40.7) | 32 (59.3) | 36 (66.7) | 18 (33.3) | 44 (81.5) | 10 (18.5) | 39 (72.2) | 15 (27.8) |

| Past | 36 (43.9) | 46 (56.1) | 10 (27.8) | 26 (72.2) | 18 (51.4) | 17 (48.6) | 31 (88.6) | 4 (11.4) | 28 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) |

| Never | 20 (14.7) | 116 (85.3) | 6 (30.0) | 14 (70.0) | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | 17 (89.5) | 2 (10.5) | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Binge drinking | ||||||||||

| Current | 33 (64.7) | 18 (35.3)** | 11 (33.3) | 22 (66.7) | 23 (69.7) | 10 (30.3)** | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | 23 (69.7) | 10 (30.3) |

| Past | 37 (72.6) | 14 (27.4) | 14 (37.8) | 23 (62.2) | 25 (69.4) | 11 (30.6) | 31 (86.1) | 5 (13.9) | 28 (75.7) | 9 (24.3) |

| Never | 40 (19.8) | 162 (80.2) | 13 (32.5) | 27 (67.5) | 16 (41.0) | 23 (59.0) | 35 (89.7) | 4 (10.3) | 28 (70.0) | 12 (30.0) |

| Unknown | - | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||||

| Marijuana Use | ||||||||||

| Current | 26 (72.2) | 10 (27.8)** | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.4)+ | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0)** | 22 (88.0) | 3 (12.0) | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) |

| Past | 34 (81.0) | 8 (19.0) | 16 (47.1) | 18 (52.9) | 19 (57.6) | 14 (42.4) | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | 24 (70.6) | 10 (29.4) |

| Never | 50 (22.1) | 176 (77.9) | 13 (26.0) | 37 (74.0) | 24 (48.0) | 26 (52.0) | 44 (88.0) | 6 (12.0) | 36 (72.0) | 14 (28.0) |

| Unknown | - | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||||

| Self-esteem | ||||||||||

| At-risk | 12 (40.0) | 18 (60.0) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7)+ | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7)* | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3)* |

| Not at risk | 98 (35.6) | 177 (64.4) | 31 (31.6) | 67 (68.4) | 55 (57.3) | 41 (42.7) | 85 (88.5) | 11 (11.5) | 74 (75.5) | 24 (24.5) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Emotional discomfort | ||||||||||

| At-risk | 21 (43.8) | 27 (56.2) | 13 (61.9) | 8 (38.1)** | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8)+ | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3)* | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9)** |

| Not at risk | 88 (34.7) | 166 (65.3) | 25 (28.4) | 63 (71.6) | 48 (55.8) | 38 (44.2) | 77 (89.5) | 9 (10.5) | 70 (79.6) | 18 (20.4) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Academic performance | ||||||||||

| At-risk | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4)+ | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0)+ | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Not at risk | 96 (34.7) | 181 (65.3) | 30 (31.3) | 66 (68.7) | 53 (56.4) | 41 (43.6) | 80 (85.1) | 14 (14.9) | 68 (70.8) | 28 (29.2) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Threat to achievement | ||||||||||

| At-risk | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3)* | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0)* | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5)+ | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5)+ | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) |

| Not at risk | 102(34.7) | 192 (65.3) | 32 (31.4) | 70 (68.6) | 57 (57.0) | 43 (43.0) | 87 (87.0) | 13 (13.0) | 74 (72.6) | 28 (27.4) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Peer influences | ||||||||||

| At-risk | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4)** | 20 (40.8) | 29 (59.2) | 37 (78.7) | 10 (21.3)** | 38 (80.9) | 9 (19.1) | 34 (69.4) | 15 (30.6) |

| Not at risk | 61 (25.4) | 179 (74.6) | 18 (29.5) | 43 (70.5) | 27 (44.3) | 34 (55.7) | 54 (88.5) | 7 (11.5) | 45 (73.8) | 16 (26.2) |

Note. Univariate analyses were performed using Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact tests (for n ≤ 5) to calculate the p-values. Missing values were ignored.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .15.

Psychological Variables

Psychological variables were also collected as part of the CHIP-AE and tested as potentially associating with the sexual risk-taking outcomes. Specific subdomains of the CHIP-AE that were considered included Self-Esteem (self-concept, satisfaction with self), Emotional Discomfort (feelings and symptoms of distress), Family Involvement (support from family members), Social Problem-Solving (individual coping with problems), Home Safety and Health (home-based prevention of harm), Threats to Achievement (negative behaviors that threaten/interrupt normative social development), Peer Influences (adolescent involvement/exposure with peers who engage in risky health behaviors), Academic Performance (assessment of academic achievements and school accomplishments), and Psychosocial Disorder (adolescent cognitive and behavioral problems).

Non-Sexual Risk Behaviors

The CHIP-AE also measures non-sexual risk behaviors including tobacco use (i.e., cigarette, smokeless tobacco), alcohol consumption (i.e., beer/wine, hard liquor/mixed drinks, binge drinking), and illicit drug use (i.e., marijuana, crack/cocaine), which were also considered in study models. These risk behaviors were assessed on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5. The five response options were then collapsed into three mutually exclusive categories with scores of 1 (past week) and 2 (past month) forming the “current use” category, scores of 3 (past year) and 4 (more than a year ago) forming the “past use” category, and a score of 5 (never) forming the “never used” category.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographic, medical, behavioral and psychological characteristics. Any scale with Cronbach’s alpha < .70 was excluded from all subsequent analyses. Comparisons utilizing Chi-square statistics or Fisher’s exact test were initially conducted. For each sexual risk behavior outcome, univariate analyses of the independent variables were performed between those with and without a history of the specified risky sexual behavior. The prevalence of risky sexual behavior was then compared in multivariate logistic regression models. After confirming the absence of multicolinearity among predictors (defined as correlation > .80), risk factors with p-values less than .15 in the univariate analyses were included in each of the models. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to evaluate goodness of fit for logistic regression models. C-statistics were used as indicators of how well the logistic regression models discriminated between observations at different levels of the outcome (> .70 indicates acceptable discrimination). Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 307 adolescent survivors completed the study questionnaire (M age = 18.1 years, SD = 1.0, range: 15.4 – 20.4 years). The majority of participants were female (59.9%), White (88.6%), and in school (58.0%). Most had parents with a college degree or higher (56.0%). Participants frequently resided in a household with an annual income of less than $60,000 (51.8%) and had some type of health insurance (81.4%). With respect to cancer-specific demographic information, the majority of participants were diagnosed prior to 2 years of age (64.5%) and were 15–20 years post diagnosis (97.7%). Diagnoses included: 54.8% solid tumors, 32.2% leukemias/lymphomas, and 13.0% CNS tumors. Most participants had received either chemotherapy only (46.9%) or chemotherapy with radiation therapy (32.2%). Over one third (37.1%) received CNS-directed therapy. See Table 1 for additional demographic information.

Table 1.

Demographic, Diagnostic, and Treatment Characteristics of Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer

| Survivors (N = 307) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 123 | 40.1 |

| Female | 184 | 59.9 |

| Age in Years | ||

| 15–17 | 129 | 42.0 |

| 18–20 | 178 | 58.0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 272 | 88.6 |

| Non-White | 35 | 11.4 |

| Education Status | ||

| In School | 178 | 58.0 |

| Not in School | 88 | 28.6 |

| Not indicated | 41 | 13.4 |

| Parent Education | ||

| Did not complete high school | 11 | 3.6 |

| High School or some college | 113 | 36.8 |

| College or higher | 172 | 56.0 |

| Don’t know | 11 | 3.6 |

| Parent Work Status | ||

| Employed | 300 | 97.7 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 1.3 |

| Retired | 2 | 0.7 |

| Student | 1 | 0.3 |

| Household Income | ||

| <60,000/yr | 159 | 51.8 |

| 60,000+/yr | 145 | 47.2 |

| Unknown | 3 | 1.0 |

| Medical Insurance | ||

| Yes | 250 | 81.4 |

| No | 30 | 9.8 |

| Canadian resident | 26 | 8.5 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.3 |

| Receiving Welfare | ||

| No | 291 | 94.8 |

| Yes | 5 | 1.6 |

| Don’t know | 11 | 3.6 |

| Receiving Food Stamps | ||

| No | 298 | 97.0 |

| Yes | 6 | 2.0 |

| Don’t know | 3 | 1.0 |

| Free Lunch | ||

| No | 286 | 93.1 |

| Yes | 19 | 6.2 |

| Don’t know | 2 | 0.7 |

| Not indicated | 0 | 0.0 |

| Age in Years at Diagnosis | ||

| 0–1 | 198 | 64.5 |

| 2–3 | 109 | 35.5 |

| Time since Diagnosis | ||

| <15 years | 6 | 2.0 |

| 15–20 years | 300 | 97.7 |

| >20 years | 1 | 0.3 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| CNS | 40 | 13.0 |

| Leukemia | 95 | 30.9 |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | 4 | 1.3 |

| Wilms tumor | 56 | 18.2 |

| Neuroblastoma | 90 | 29.3 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 19 | 6.3 |

| Bone cancer | 3 | 1.0 |

| Treatment Modalities | ||

| Surgery only | 41 | 13.4 |

| Radiation therapy (no chemo) | 11 | 3.6 |

| Chemotherapy + radiation | 99 | 32.2 |

| Chemotherapy (no radiation) | 144 | 46.9 |

| No chemo, surgery, or radiation | 2 | 0.7 |

| Unknown | 10 | 3.3 |

| CNS Treatment | ||

| No CNS treatment | 193 | 62.9 |

| Any CNS treatment | 114 | 37.1 |

Univariate Factors Associated with Risky Sexual Behavior

Univariate differences in sexual history, early initiation of sexual activity, history of multiple sexual partners, use of pregnancy prevention, and utilization of STI prevention were assessed as a function of sociodemographic, medical, behavioral, and psychological variables (see Table 2). In brief, older adolescents were more likely to report a history of sexual intercourse (p < .01), while younger participants were more likely to report early initiation of sexual intercourse (p < .01). Lower parental education was associated with increased participant history of sexual intercourse (p = .02), multiple sexual partners (p = .03), and increased utilization of STI prevention at last intercourse (p = .04). Those with a history of CNS malignancy were less likely to report a history of sexual intercourse (p < .05), but sexually experienced survivors who received treatment to the CNS were more likely to report having multiple partners (p = .03). Survivors who reported a history and/or current cigarette use, marijuana use, and binge drinking behaviors were more likely to report a history of sexual intercourse (ps ≤ .01) and having had multiple partners (ps ≤ .01). Increased threats to achievement were associated with increased participant history of sexual intercourse (p = .02) and early sexual debut (p = .02), whereas increased negative peer influences related to increased history of sexual intercourse and multiple sexual partners (ps < .01). Among psychological risk factors, poor self-esteem and emotional discomfort were associated with a lack of pregnancy prevention (ps = .02) or STI prevention (ps < .05) at last intercourse. There were no univariate differences in history of sexual intercourse, early initiation of sexual activity, history of multiple sexual partners, or utilization of a form of pregnancy or STI prevention as a function of race or household income.

Multivariate Models of Sexual Behavior

History of sexual intercourse (Table 3)

Table 3.

Comparison of Sociodemographic and Other Variables of Interest between Adolescent Cancer Survivors With and Without History of Sexual Intercourse

| Identified Relevant Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 2.23 | 0.99–5.02 | 0.05 |

| Age | |||

| 14–17 | 1.00 | ||

| 18–20 | 1.81 | 0.70–4.71 | 0.22 |

| Education Status | |||

| In School | 1.00 | ||

| Not in School | 1.86 | 0.69–5.01 | 0.22 |

| Not indicated | - | - | - |

| Parent Education | |||

| Less than college grad | 1.00 | ||

| College grad or higher | 0.58 | 0.27–1.25 | 0.17 |

| Don’t know | - | - | - |

| Time since diagnosis | |||

| Median split low | 1.00 | ||

| Median split high | 1.55 | 0.65–3.70 | 0.33 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Leukemia | 1.00 | ||

| CNS | 0.13 | 0.02–0.96 | 0.05 |

| Neuroblastoma | 0.32 | 0.07–1.47 | 0.14 |

| Other | 0.89 | 0.21–3.80 | 0.87 |

| CNS Treatment | |||

| No CNS treatment | 1.00 | ||

| CNS treatment | 0.37 | 0.09–1.52 | 0.17 |

| Cigarette Use | |||

| Current | 1.00 | ||

| Past | 1.62 | 0.37–7.01 | 0.52 |

| Never | 0.61 | 0.18–2.12 | 0.44 |

| Unknown | - | - | - |

| Beer/wine Use | |||

| Current | 1.00 | ||

| Past | 0.62 | 0.18–2.08 | 0.44 |

| Never | 0.20 | 0.06–0.68 | 0.01 |

| Unknown | - | - | - |

| Binge Drinking | |||

| Current | 1.00 | ||

| Past | 3.02 | 0.64–14.15 | 0.16 |

| Never | 1.31 | 0.33–5.21 | 0.70 |

| Unknown | - | - | - |

| Marijuana Use | |||

| Current | 1.00 | ||

| Past | 1.80 | 0.33–9.79 | 0.49 |

| Never | 0.29 | 0.07–1.33 | 0.11 |

| Unknown | - | - | - |

| Academic performance | |||

| At-risk | 1.00 | ||

| Not at risk | 3.25 | 0.58–18.14 | 0.18 |

| Missing | - | - | - |

| Threats to achievement | |||

| At-risk | 1.00 | ||

| Not at risk | 0.60 | 0.09–4.02 | 0.60 |

| Missing | - | - | - |

| Peer influences | |||

| At-risk | 1.00 | ||

| Not at risk | 0.28 | 0.09–0.84 | 0.02 |

| Missing | - | - | - |

Note. N = 307

Based on results from the univariate analyses (Table 2), the following variables were included in the multivariate model testing factors associated with engagement in sexual intercourse among adolescent cancer survivors: gender, age, educational status, parent education, time since diagnosis, diagnosis, history of CNS treatment, cigarette use, beer/wine use, history of binge drinking, marijuana use, academic performance, threats to achievement, and peer influences. Using a positive history of sexual intercourse as the outcome, results of the multivariate logistic regression revealed that a CNS diagnosis (OR = .13, 95% CI: .02 – .96, p = .05), no history of beer/wine consumption (OR =.20, CI: .06 – .68, p = .01), and few negative peer influences (OR = .28, CI: .09 – .84, p =.02) associated with a decreased likelihood of having a history of sexual intercourse (Table 3).

Age at sexual debut

The following variables were included in the multivariate model identifying predictors of age at sexual debut (i.e., age at first sexual intercourse): age, time since diagnosis, diagnosis, cigarette use, marijuana use, self-esteem, emotional discomfort, and threats to achievement. Using younger age of initiation of sexual intercourse (i.e., < 16 years of age) as the outcome, good psychological health (i.e., not at risk for significant emotional discomfort) associated with a decreased likelihood of having engaged in early sexual intercourse (OR =.19, CI: .05 – .77, p = .02).

Lifetime history of sexual partners

The following variables were included in the multivariate model considering lifetime history of multiple sexual partners (i.e., one partner versus two or more partners): parent education, CNS treatment, cigarette use, history of binge drinking, marijuana use, emotional discomfort, and threats to achievement. Academic performance was also a significant univariate predictor of number of sexual partners; however, it was excluded from the multivariate model due to the (right) skewed distribution of the sample. Survivors whose parents had a college degree or higher were less likely to report having had multiple sexual partners (OR = .25, CI: .09 – .72, p = .01).

Pregnancy prevention efforts

The following variables were included in the multivariate model identifying predictors of contraception use at last sexual intercourse: parent education, self-esteem, emotional discomfort, and threats to achievement. None of the factors included in the model were found to independently associate with contraception use.

Sexually transmitted infection prevention efforts (Table 4)

Table 4.

Comparison of Sociodemographic and Other Variables of Interest for Sexually Active Adolescent Cancer Survivors by No Condom Use at Last Intercourse

| Identified Relevant Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Education | |||

| Less than college grad | 1.00 | ||

| College grad or higher | 4.27 | 1.46–12.52 | 0.01 |

| Don’t know | - | - | - |

| Time since diagnosis | |||

| Median split low | 1.00 | ||

| Median split high | 0.27 | 0.10–0.78 | 0.02 |

| Self-Esteem | |||

| At-risk | 1.00 | ||

| Not at risk | 0.78 | 0.16–3.78 | 0.76 |

| Missing | - | - | - |

| Emotional discomfort | |||

| At-risk | 1.00 | ||

| Not at risk | 0.09 | 0.02–0.36 | <0.01 |

| Missing | - | - | - |

The following variables were included in the multivariate model identifying predictors of condom use at last sexual intercourse: parent education, time since diagnosis, self-esteem, and emotional discomfort. Survivors who were further from diagnosis (OR = .27, CI: .10 – .78, p = .02) or who were psychologically healthy (OR = .09, CI: .02 – .36, p < .01) were less likely to report unprotected sex at last intercourse. However, having parents with college degrees or higher was associated with a greater likelihood to engage in unprotected sex (OR = 4.27, CI: 1.46 – 12.52, p = .01).

Discussion

Adolescent survivors of childhood cancer engage in risky sexual behavior at rates equivalent to sibling controls (Klosky et al., 2012). This is concerning in that adolescents with a cancer history are already at increased likelihood for developing later health complications, including second cancers, and these risks may be exacerbated by engagement in risky behaviors. Given this predisposition, the present study systematically examined factors associated with sexual risk taking among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. This included consideration of cancer-specific/biological, social, psychological, developmental, and environmental risk/protective factors, which have been previously described in Jessor and colleagues’ Problem Behavior Theory (PBT) as contributing to risky behavior among typically developing adolescent populations (Jessor, 1993; Jessor, et al., 1995).

In regard to cancer-specific variables, history of CNS malignancy was related to lower risk of sexual intercourse history, whereas greater time since diagnosis associated with increased STI prevention behaviors. These findings are consistent with those of Sundberg and colleagues (2011), who found that among adult survivors of childhood cancer, males with a history of CNS tumor reported fewer sexual partners (both within the preceding year and over one’s lifetime) relative to healthy controls. Survivors of CNS tumor also experience greater difficulties in cognitive and social functioning. All participants in the current study were diagnosed prior to age 4, and this younger age group is known to be at particularly high risk for cognitive late effects resulting from CNS-directed cancer therapies. While it is optimistic that adolescent survivors experience an increased likelihood for engaging in STI prevention as time from diagnosis increases, it is concerning that similar safer-sex behaviors are less frequently reported closer to the conclusion of treatment. This is disconcerting considering that cancer survivors are most likely to be immunocompromised while on or shortly after completing cancer-directed therapy, placing them at greater risk for health complication should they acquire an STI during this period.

This finding highlights the need for implementing psychoeducational interventions earlier in the cancer trajectory for the promotion safer sexual behaviors, particularly during periods of elevated health vulnerability. For this group, interventions created for typically developing adolescents should be expanded upon to address survivor-specific concerns such as perceived infertility and health vulnerabilities, in addition to consequences of STI acquisition including second cancers. By taking advantage of the increased patient contacts associated with cancer care, health care providers could then not only deliver these interventions to patients but to their partners as well. For the promotion of health in the youngest survivors, oncology centers could also offer parent trainings for the encouragement of parent-child conversations on protective behaviors and sexual risk taking from the survivorship perspective. Our data suggests that having well educated parents does not protect adolescents from engaging in unsafe sex. As such, delivery of safe sex messages by informed health care providers could be particularly beneficial in this group.

Having never consumed beer/wine and having fewer negative peer influences were also associated with a reduced likelihood of ever having engaged in sexual intercourse. These results are consistent with numerous studies that link alcohol use, impaired decision-making, and risky sexual behavior among both typically developing and chronically ill populations (Draus, Santos, Franklin, & Foley, 2008; Sutherland & Shepherd, 2001; Valencia & Cromer, 2000). These findings are also consistent with PBT, which cites alcohol use (behavior domain) and peer influences (perceived influence domain) as promoting adolescent engagement in risky sexual behavior (Jessor, 1993; Jessor et al., 1995). As previously stated, adolescents surviving cancer are often at risk for cognitive late effects, including impulsivity, inattention, poor planning and decision-making, which may in turn promote susceptibility to being influenced by negative peer pressure (Conklin et al., 2010; Moleski, 2000; Mulhern et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2003; Pietilä et al., 2012; Ris & Noll, 1994; Walter et al., 1999). When these risks are combined with survivors’ desires to establish and maintain peer relations/group membership (along with perceptions of invincibility/optimistic bias), engagement in sexual risk-taking may increase. Currently, school reintegration programs for survivors focus primarily on academic needs (Keene, 2003). Based on the results of this study, it appears that social concerns should also be addressed, with an emphasis on coping with negative peer influences and minimizing risky (i.e., sexual) behaviors. Highlighting the relations between engagement in risky behaviors (e.g., alcohol use, illicit drug use, etc.), impaired decision-making (both as a function of cancer late effects and typical adolescent brain development), and unplanned risky sexual encounters is indicated as well.

Adolescent survivors reporting better psychological health were more likely to have later sexual debut. Consistent with PBT, this suggests that psychological well-being may act as a protective factor buffering against early sexual contacts. Similar results were reported by Donenberg and colleagues (2003), who found that adolescents with impaired social functioning and increased externalizing behavior were more likely to report earlier sexual debut. Specific impairments described in Donenberg’s study included perceived problems with parents and negative peer influences. Among adolescents, lower self-esteem (a construct related to psychological health) has been consistently linked with earlier sexual debut and riskier sexual behavior, while emotional distress has been related to greater likelihood of previous STI, greater number of sexual partners, and having riskier sexual partners (Ethier et al., 2006). Collectively, these findings highlight the impetus for developing health promoting interventions that focus on modifying psychological variables, such as improving emotional functioning, as a means of reducing risky sexual behavior in survivors. As such, these adolescents could also benefit from learning about the associations between poor mental health and risky sexual behavior in a group context (e.g., group therapy, virtual and in-person structured support groups, retreats, conferences, etc.). Providing forums for these discussions helps to reduce stigma surrounding mental health difficulties secondary to cancer treatment, while also highlighting the normative developmental challenges that exist for most adolescents, such as navigating peer and romantic relationships, refraining from substance use, and making healthy decisions about sexual behavior.

Although this is the largest study to date to report on correlates of risky sexual behavior among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer, the study design was cross-sectional, utilized a pragmatic (as opposed to theoretical) approach to model building, included only those diagnosed between 0 and 4 years of age, included an overrepresentation of female and White participants, and relied on self-report which introduces potential bias and limits generalizability. Rates of participation were also presumably suboptimal due to the method of participant enrollment. However, when assessing risky sexual behavior and associated factors, our outlined mailed questionnaire approach may possess significant advantages over more traditional methods. Previous studies have questioned the validity of adolescent survey responses when eliciting sensitive information in the medical setting (Horm et al. 1996; Griesler et al., 2008). While in clinic, adolescent survivors may feel inadvertently pressured to under-report risky health behavior in the presence of parents and/or the medical team (Kann et al., 2002; Patrick et al., 1994; Velicer et al., 1992). Questionnaire completion in the private home setting (as was the case in this study) may reduce this risk by allowing increased anonymity and confidentiality, which, in turn, may promote the disclosure of more valid reporting. Future research may benefit from expanding data collection to a young adult population and/or inclusion of participants diagnosed with cancer in adolescence, as these groups may be qualitatively different (but with increased health risk) with respect to sexual risk-taking behavior.

With the discovery that HPV causes cervical and other cancers, risky sexual behavior has recently been highlighted as an important health behavior that has distinct implications for childhood cancer survivors. As survivors are at risk for altered immunity (particularly those treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or pelvic irradiation, or those diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma), they may be at relatively higher risk for HPV-related complication secondary to infection (Klosky et al., 2009). Fortunately, two HPV vaccinations have recently been FDA-approved in the US, and the Children’s Oncology Group’s Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Version 3.0 has recommended HPV vaccination for all eligible females surviving childhood cancer (American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hematology/Oncology, Children’s Oncology Group, 2009). Although it is encouraging that 72–84% of sexually active survivors reported use of a method to prevent pregnancy or STI at last intercourse, HPV is transmitted via skin-to-skin contact, suggesting that all sexually active survivors are at-risk for infection regardless of whether or not standard methods of pregnancy protection and/or STI are utilized.

Although not directly assessed in this study, infertility among survivors (and perceptions thereof) and its relation to risky sexual behavior should also be considered for future research. This is important as survivors who perceive themselves as being infertile may engage in riskier sexual behaviors (Zebrack et al., 2004) and are more likely to report having experienced a high-risk HIV transmission situation (Phillips-Salimi et al., 2012). As demonstrated by the gender trend in the sexual intercourse model, this may be particularly applicable to female survivors who often erroneously attribute treatment-related interruptions in menses with infertility (Murphy, Klosky, Termuhlen, Sawczyn, & Quinn, 2013). Alternately, survivors with suspected infertility have reported engaging in condom use to appear fertile and avoid having to disclose their infertility status (Crawshaw & Sloper, 2010). Adding to the difficulties of adapting to potential infertility, survivors are frequently unsure about their fertility status (Oosterhuis et al., 2008; Schover et al., 2002), and this lack of clarity may also contribute to the relatively high rates of psychological distress frequently reported in this population.

By identifying and considering modifiable correlates of risky sexual behavior, interventions can best be designed and tested for reducing sexual risk taking in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. By reducing this behavior, one should expect subsequent declines in unintended pregnancy, STIs, and associated cancers. The pursuit of this work will not only result in improved health, but in quality of life outcomes in this vulnerable group.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI grant CA 55727 (L.L. Robison, Principal Investigator), ACS Grant RSG-01-021-01-CCE (A.C. Mertens, Principal Investigator), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

References

- Barzon L, Pizzighella S, Corti L, Mengoli C, Palù G. Vaginal dysplastic lesions in women with hysterectomy and receiving radiotherapy are linked to high-risk human papillomavirus. Journal of Medical Virology. 2002;67:401–405. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Louie AD, Bhatia R, O’Donnell MR, Fung H, Kashyap A, Forman SJ. Solid cancers after bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:464–471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.464. Retrieved from http://jco.ascpubs.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Yasui Y, Robison LL, Birch JM, Boque MK, Diller L, Meadows AT. High risk of subsequent neoplasms continues with extended follow-up of childhood Hodgkin’s disease: Report from the Late Effects Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(23):4386–4394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual risk behavior: HIV, STD & Teen Pregnancy Prevention. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/sexualbehaviors/

- Clarke SA, Eiser C. Health behaviours in childhood cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43(9):1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin HM, Helton S, Ashford J, Mulhern RK, Reddick WE, Brown R, Khan RB. Predicting methylphenidate response in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(2):144–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawshaw MA, Sloper PP. ‘Swimming against the tide’—The influence of fertility matters on the transition to adulthood or survivorship following adolescent cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2010;19(5):610–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolson EP, Conklin HM, Li C, Xiong X, Merchant TE. Predicting behavioral problems in craniopharyngioma survivors after conformal radiation therapy. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2009;52(7):860–864. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Bryant FB, Emerson E, Wilson HW, Pasch KE. Tracing the roots of early sexual debut among adolescents in psychiatric care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):594–608. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046833.09750.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus JM, Jr, Santos AP, Franklin GAB, Foley DS. Drug and alcohol use among adolescent blunt trauma patients: Dying to get high? Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2008;43:208–211. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. Journal of American Medical Association. 2007;297(8):813–819. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K. Smoking among childhood cancer survivors: We can do better. Journal of National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(15):1048–1049. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K, Li FP, Whitton J, Mertens AC, Hutchinson R, Diller L, Robison LL. Predictors of smoking initiation and cessation among childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(6):1608–1616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier KA, Kershaw TS, Lewis JB, Milan S, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR. Self-esteem, emotional distress and sexual behavior among adolescent females: Interrelationships and temporal effects. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(3):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB, Schaffran C, Hu MC, Davies M. Adolescents’ inconsistency in self-reported smoking: A comparison of reports in school and in household settings. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(2):260–290. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Lu B, Nielson CM, Flores R, Papenfuss MR, Lee JH, Harris RB. Age-specific prevalence, incidence, and duration of human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of 290 US men. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198(6):827–835. doi: 10.1086/591095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter FJ, Wallnau LB. Statistics for the behavioral sciences. 6. Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Horm J, Cynamon M, Thornberry O. The influence of parental presence on the reporting of sensitive behaviors by youth. In: Warnecke R, editor. Health Survey Research Methods: Conference Proceedings (DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 96-1013. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Hobbie W, Chen H, Gurney JG, Oeffinger KC. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Successful adolescent development among youth in high- risk settings. American Psychologist. 1993;48(2):117–126. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Van De Bos J, Vanderryn J, Costa FM, Turbin MS. Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(6):923–933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Brener ND, Warren CW, Collins JL, Giovino GA. An assessment of the effect of data collection setting on the prevalence of health risk behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(4):327–335. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene N, editor. Educating the child with cancer: A guide for parents and teachers. Kensington, MD: American Childhood Cancer Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Klosky JL, Gamble HL, Spunt SL, Randolph ME, Green DM, Hudson MM. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5627–5636. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosky JL, Howell C, Zhenghong L, Foster RH, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Ness KK. Risky behavior among adolescents in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37(6):634–646. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull K, Huang S, Gurney J, Klosky J, Leisenring W, Termuhlen A, Hudson M. Adolescent behavior and adult health status in childhood cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(3):634–646. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moleski M. Neuropsychological, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological consequences of CNS chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2000;15:603–630. doi: 10.1093/arclin/15.7.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhern RK, White HA, Glass JO, Kun LE, Leigh L, Thompson SJ, Reddick WE. Attentional functioning and white matter integrity among survivors of malignant brain tumors of childhood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10:180–189. doi: 10.1017/S135561770410204X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Klosky JL, Termuhlen A, Sawczyn KK, Quinn GP. The need for reproductive and sexual health discussions with adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Contraception. 2013;88(2):215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebbitt VE, Lombe M, Sanders-Phillips K, Stokes C. Correlates of age at onset of sexual intercourse in African American adolescents living in urban public housing. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(4):1263–1277. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Robison LL. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. Retrieved from www.nejm.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha RP, Tota JE, Offutt-Powell TN, Klosky JL, Minniear TD, Jackson BE, Gurney JG. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated subsequent malignancies among long-term survivors of pediatric and young adult cancers. PloS One. 2013;8(8):e70349. doi: 10.137/journal.pone.0070349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhuis EB, Goodwin T, Kiernan M, Hudson MM, Dahl GV. Concerns about infertility risks among pediatric oncology patients and their parents. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2008;50(1):85–89. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SL, Gajjar A, Reddick WE, Glass JO, Kun LE, Wu S, Mulhern RK. Predicting intellectual outcome among children treated with 35–40_Gy craniospinal irradiation for medulloblastoma. Neuropsychology. 2003;17:548–555. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Weaver TE, Romer D. Predictors of the transition from experimental to daily smoking in late adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Drug Education. 2010;40(2):125–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: A review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. Retrieved from ajph.aphapublications.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Salimi CR, Lommel K, Andrykowski MA. Physical and mental health status and health behaviors of childhood cancer survivors: Findings from the 2009 BRFSS survey. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2012;58(6):964–970. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietilä S, Korpela R, Lenko HL, Haapasalo H, Alalantela R, Nieminen P, Mäkipernaa A. Neurological outcome of childhood brain tumor survivors. Journal of Neurooncology. 2012;108(1):153–161. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0816-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ris MD, Noll RB. Long–term neurobehavioral outcome in pediatric brain – tumor patients: Review and methodological critique. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology. 2000;16(1):21–42. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasadeusz J, Kelly H, Szer J, Schwarer AP, Mitchell H, Grigg A. Abnormal cervical cytology in bone marrow transplant receipts. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:393–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703141. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/bmt/index.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvageau C, Duval B, Gilca V, Lavoie F, Ouakki M. Human papilloma virus vaccine and cervical cancer screening acceptability among adults in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):304–310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Simons RL, Whitebeck LB. Predicting risk of pregnancy by late adolescence: A social contextual perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(6):1233–1245. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schover LR, Brey K, Lichtin A, Lipshultz LI, Jeha S. Knowledge and experience regarding cancer, infertility, and sperm banking in younger male survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(7):1880–1889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Bergner M, Riley A, Ensminger ME, Green B, Ryan Johnston D. Child Health and Illness Profile-Adolescent Edition (CHIP-AE) Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Riley AW, Green BF, Ensminger ME, Ryan SA, Kelleher K, Vogel K. The adolescent child health and illness profile. A population-based measure of health. Medical Care. 1995;33:553–566. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Forrest CB, Ryan SA, Riley AW, Ensminger ME, Green BF. Health status of well vs ill adolescents. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:1249–1256. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170370027003. Retrieved from pubs.ama-assn.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TK, Zimmerman R, Lynam D, Milich R, Clayton R. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among young adults. Health and Social Work. 1999;24(2):147–154. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolley MR, Restrepo J, Sharp LK. Diet and physical activity in childhood cancer survivors: A review of the Literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(3):232–249. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland I, Shepherd JP. Social dimensions of adolescent substance use. Addiction. 2001;96:445–458. doi: 10.1080/0965214002005419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Gerhardt CA, Miller KS, Vannatta K, Noll RB. Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Comparison Peers: the Influence of Peer Factors on Later Externalizing Behavior in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter AW, Mulhern RK, Gajjar A, Heideman RL, Reardon D, Sanford RA, Kun LE. Survival and neurodevelopmental outcome of young children with medulloblastoma at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:3720–3728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3720. Retrieved from jco.ascopubs.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia LS, Cromer BA. Sexual activity and other high-risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic illness: A review. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2000;13:53–64. doi: 10.1016/S1083-3188(00)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Stovall M, Hagenbeek A, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Noyon R, Somers R. Roles of radiotherapy and smoking in lung cancer following Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of National Cancer Institute. 1995;87(20):1530–1537. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.20.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn EL, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Academic and social motives and drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2009;23(4):564–576. doi: 10.1037/a0017331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazsonyi AT, Chen P, Young M, Jenkins D, Browder S, Kahumoku E, Michaud PA. A test of Jessor’s problem behavior theory in a Eurasian and a Western European developmental context. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(6):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(1):23–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspective on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. Retrieved from www.guttmacher.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulf D. In their own right: Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of American men. New York, NY: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, Zeltzer LK. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):689–699. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]