Abstract

Background

Although potassium-binding sodium-based resins (K resins) have been prescribed to treat hyperkalemia for 50 years, there have been no large studies of their effects among hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Data from 11,409 patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study in Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, and Sweden (nations where ≥ 5% of patients were prescribed a sodium based K resin; seven other countries had <5% use) between 2002-2011 were analyzed. Linear mixed models examined associations between K resin use and interdialytic weight gain (IDWG) and serum electrolyte concentrations. Mortality was analyzed using Cox regression. An instrumental variable approach was used to partially account for unmeasured confounders.

Results

The K resin prescription rate was 20% overall. As hypothesized, patients prescribed a K resin had greater IDWG and higher serum bicarbonate, phosphorus, and sodium (but not calcium) concentrations. Patients prescribed a K resin had higher serum K, but lower serum K in an instrumental variable analysis to limit treatment by indication bias. K resin use was not associated with mortality risk.

Conclusion

We report the first large study of K resin use and associated lab and clinical outcomes in HD patients. The prescription rate of K resins varied dramatically by country and dialysis center. The results suggest that K resin use may effectively lower serum K, although at the expense of somewhat higher phosphatemia and greater IDWG, and had no clear association with mortality. Additional study is warranted to elucidate the optimal role for K resins in modern dialysis care.

Keywords: calcium, dialysis, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study, mortality, phosphatemia, potassium-binding resins, survival

INTRODUCTION

The use of potassium-binding resins (K resins) to treat hyperkalemia began more than 50 years ago [1-2] and sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate®) was approved soon thereafter for use in the United States (US). There is a remarkable paucity, however, of literature addressing clinical outcomes of binder prescription. It would be of interest to examine whether use of sodium based (Na based) K resins is associated with greater interdialytic weight gain (IDWG), caused by sodium absorption and consequent fluid ingestion due to thirst. Additionally, van Ypersele [3] demonstrated in 1980 that oral administration of Na-based K resins increases phosphaturia and plasma bicarbonate concentration in dogs with normal renal function. He ascribed these findings to calcium (Ca) binding by the resin in the bowel, increasing phosphorus and bicarbonate solubility and favoring their intestinal absorption. Whether these findings apply to hemodialysis (HD) patients is unknown. In addition, whether K resins effectively and safely reduce K level remains currently debated [4-5]. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) prospectively collects medication data, pre- and post-dialysis weight, and laboratory values on thousands of HD patients internationally, providing an opportunity to investigate patterns of Na-based K resin prescription and their associations with serum electrolyte concentrations and IDWG. Our hypothesis was that the intake of Na-based K resins would be associated with a higher IDWG (due to the sodium load) and higher serum levels of sodium, phosphate and bicarbonate. We also expected Na-based K resins to lower serum K concentrations.

METHODS

Patients and Data Collection

The DOPPS is an international prospective cohort study of HD patients ≥ 18 years of age, enrolled randomly from a representative sample of dialysis facilities within each country, as described previously [6-7]. The current study analyzes data from the DOPPS phase 2 (2002-2004), phase 3 (2005-2008), and phase 4 (2009-2011). Study approval was obtained by a central institutional review board. Additional study approval and patient consent were obtained as required by national and local ethics committee regulations. Demographic data, comorbid conditions, laboratory values, pre- and post-dialysis weight, and medications were abstracted from patient records.

Definitions

K resin use was defined as having a prescription for a Na-based K resin at study entry. Patients without medication records at study entry were excluded from analysis. Countries with K resin use among < 5% of patients during DOPPS 4 were excluded. The United Kingdom, Spain, and Japan were < 1%; The US, Australia/New Zealand, and Germany were 1-3%. Ca-based K resins were used in DOPPS 4 in Spain (13%) and Japan (9%), but not in the remaining DOPPS countries (< 1%). As Ca-based K resins were used in only two countries and not used concurrently with Na-based resins in any country, Ca-based K resins were excluded from this analysis. Overall, 11,409 HD patients from 288 facilities in Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, and Sweden were used for this analysis.

Data Analysis

We calculated the overall percentage of patients within each nation who were prescribed K resin, and also characterized the frequency of K resin use across facilities in each country. Logistic regression using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for facility clustering was used to test the trend in patient K resin use by phase. Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe patient characteristics. Baseline characteristics of patients prescribed K resin and not prescribed K resin were compared using linear mixed models for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables, adjusting for DOPPS phase and country, and accounting for facility clustering effects.

The primary exposure of interest was K resin use and the primary outcomes of interest were IDWG and serum concentrations of bicarbonate, phosphorus, K, Ca, and Na, also measured at study entry. Linear mixed models were used to examine the associations between K resin use and these outcomes, accounting for clustering with a random facility intercept. Models were adjusted for DOPPS phase, country, age, gender, black race, vintage, body mass index, residual kidney function, HD vascular access type, serum ferritin, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, serum albumin, serum creatinine, dialysate K, and the 14 comorbid conditions listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics by Potassium-Binding Resin Prescription.

| Patient Characteristic (mean ± standard deviation or %) |

Prescribed K Resin | Not on K Resin | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2296 (20%) | 9113 (80%) | |

| Age (years) | 63.4 ± 14.6 | 65.6 ± 14.6 | < 0.001 |

| Vintage (years) | 5.4 ± 5.1 | 3.4 ± 5.4 | < 0.001 |

| Male | 60% | 59% | 0.71 |

| Black race | 3% | 3% | 0.72 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 5.5 | 25.6 ± 5.4 | 0.05 |

| Residual kidney function** | 37% | 50% | < 0.001 |

| Vascular access | < 0.001 | ||

| Arteriovenous fistula | 68% | 55% | |

| Graft | 7% | 6% | |

| Catheter | 22% | 36% | |

| Unknown Access | 3% | 3% | |

| Dialysate potassium (mEq/L) | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.5 ± 1.6 | 11.3 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 443 ± 417 | 405 ± 415 | < 0.001 |

| White blood cell count (1000/m3) | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 7.3 ± 2.5 | 0.01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 8.9 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.2 ± 3.5 | 137.9 ± 3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 22.9 ± 3.5 | 22.9 ± 3.4 | 0.32 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 5.1 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

| Interdialytic weight gain (%) | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Interdialytic weight gain (kg) | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 40% | 46% | 0.04 |

| Cancer (non-skin) | 16% | 16% | 0.99 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 39% | 38% | 0.13 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 17% | 18% | 0.97 |

| Coronary heart failure | 32% | 30% | 0.06 |

| Diabetes | 30% | 37% | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | 4% | 6% | < 0.001 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 0% | 0% | 0.08 |

| Hypertension | 82% | 81% | 0.07 |

| Lung Disease | 12% | 15% | 0.33 |

| Neurologic disease | 11% | 12% | 0.80 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 17% | 17% | 0.18 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 32% | 32% | 0.13 |

| Recurrent cellulitis or gangrene | 9% | 9% | 0.68 |

P-value tests difference between groups, adjusting for DOPPS phase and country

Residual kidney function defined as urine output >200 mL/day on or before the enrollment date

To partially account for patient-level unmeasured confounders that may impact the relationship between K resin use and outcomes, we also conducted a separate set of analyses applying an instrumental variable approach [8-9]. The standard two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) [10,11] instrumental variable method for continuous outcomes was implemented. Chen et al [12] provides a review of instrumental variable analyses in prescription drug research with observational data, including Stuart et al [13] which implements the 2SRI approach. Stage 1 treated K resin prescription as the outcome and used the dialysis facility as the instrument to predict the treatment in a fully adjusted model. Stage 2 used the linear mixed model approach described above, but with an additional adjustment for the residual obtained from the Stage 1 model. This approach helps to account for confounding by indication, specifically patients with higher serum K being more likely to be prescribed K resin, which standard covariate adjustment is unable to address. Because lower dialysate K was likely prescribed to patients with high serum K [14], we would expect additional confounding by indication to occur. We thus treat both K resin and dialysate K as endogenous variables in instrumental variable analyses in order to simultaneously account for the confounding by indication caused by each variable. This instrumental variable approach consists of two separate stage 1 models with K resin and dialysate K as respective outcomes; we then add the residual from each model as additional adjustments into a single Stage 2 model using the 2SRI approach.

If Na-based resins increase serum phosphorus concentration, this might trigger phosphate binder (PB) prescription. Thus, an adjusted multinomial logistic regression model was used to assess the association of K resin use with PB use. PB use was the outcome and was categorized into four groups: (1) Ca and/or Magnesium (Mg) based PB only, (2) Ca and/or Mg based PB plus additional type of PB, (3) Other type of PB (not Ca or Mg based; primarily sevelamer), (4) Not prescribed any PB. PB use (any PB yes/no) was also investigated as an effect modifier in the primary analyses.

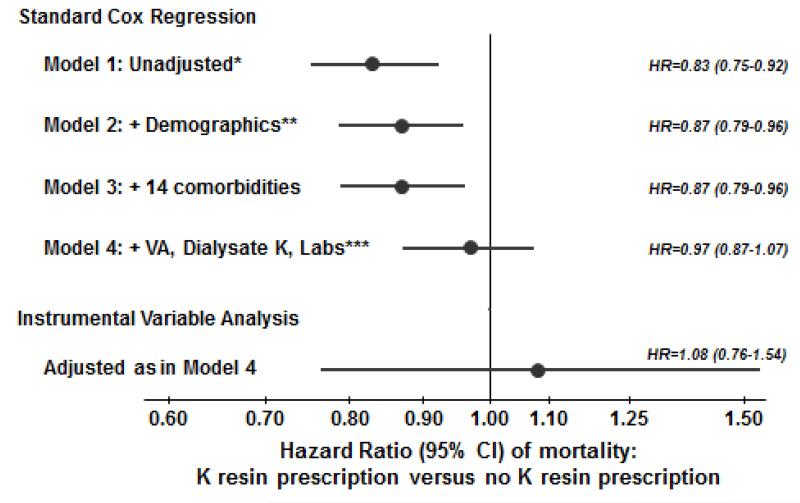

Cox regression was used to estimate the association between K resin prescription and mortality, stratified by country and phase, and accounted for facility clustering using robust sandwich covariance estimators. Adjustment was made for expanding sets of covariates listed in Figure 2. Time at risk started at study enrollment and ended at the time of death, seven days after leaving the facility due to transfer or change in renal replacement therapy modality, loss to follow-up, transplantation, end of study phase, or the most recent date of data availability (whichever event occurred first). In addition, a modified 2SRI instrumental variable approach, with a second stage Cox model, was used to partially account for patient-level unmeasured confounders [10]. Proportional hazards were confirmed by testing log(time) interactions and examining log-log survival plots.

Figure 2.

Association between K resin prescription and mortality, by levels of adjustment. *Unadjusted Cox model stratified by DOPPS phase and country and accounted for facility clustering; **Demographics: age, gender, black race, body mass index, vintage, residual kidney function; ***Labs: serum albumin, creatinine, ferritin, hemoglobin, white blood cell count; VA=vascular access.

For missing data, we used the Sequential Regression Multiple Imputation Method implemented by IVEware [15]. Results from five imputed data sets were combined for the final analysis using Rubin’s formula [16]. The proportion of missing data was below 10% for all imputed covariates, with the exception of bicarbonate (24%), IDWG (19%), ferritin (14%), albumin (11%), and white blood cell count (11%). All analyses used SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

K resin use

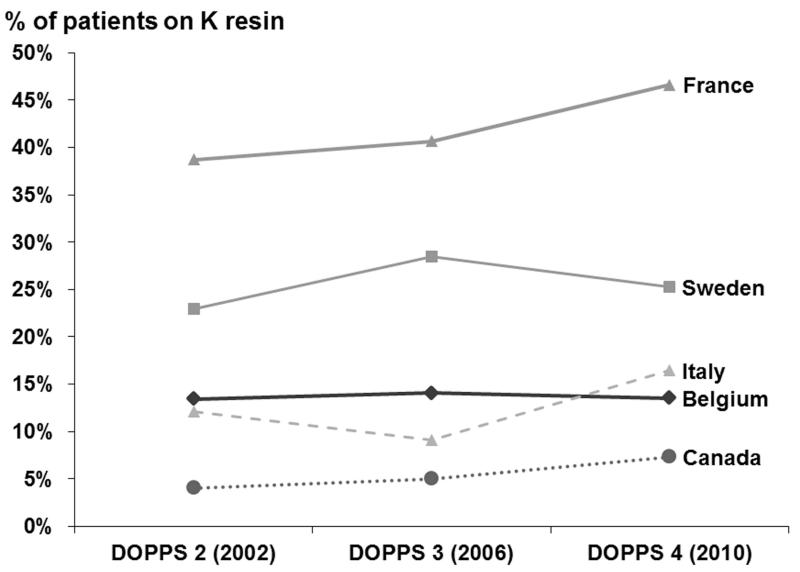

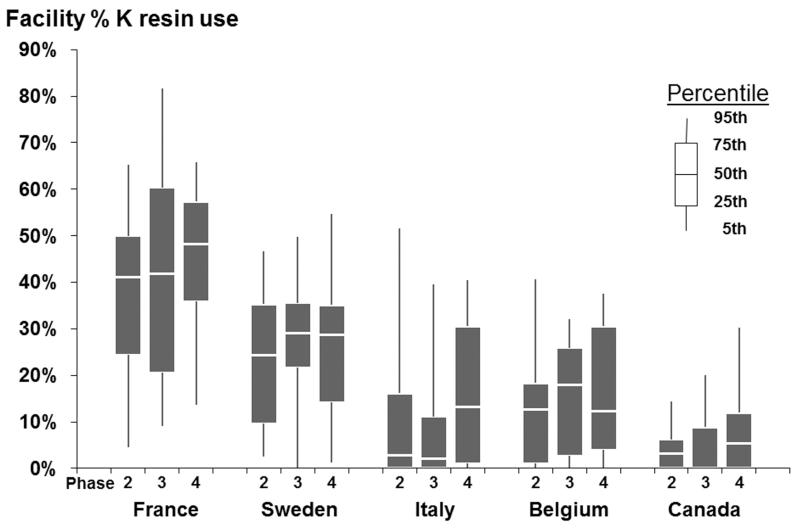

Among the overall 11,409 HD patients at study entry, K resin use was 20%. K resin prescription rates varied across countries: 42% of patients in France were prescribed K resin, 25% in Sweden, 14% in Belgium, 13% in Italy, and 5% in Canada. K resin use was consistently highest in France across study phases (Figure 1A). No clear trend in K resin use across study phases was found in any country. Percentage of patients within a facility that were prescribed K resin varied, as shown in Figure 1B. Overall, the 95th percentile of facility K resin use was 58%, and 20% of facilities did not prescribe K resin to any patients. The dose and frequency of K resin prescriptions varied widely. The three most common prescriptions were for 15 g daily (N=273, 105 g/week), 15 g once per week (N=223), and 15 g four times per week (N=161, 60 g/week).

Figure 1A.

Trends in Na based K Resin prescription, by DOPPS country. K resin prescription was not significantly different (p>0.05) across study phases in any country.

Figure 1B.

Facility percentage K resin prescription, by DOPPS country and phase.

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients on K resin at study baseline compared to patients not on K resin at study baseline. Those on K resin had higher vintage, serum albumin, hemoglobin, ferritin, creatinine, Ca, K, Na, and phosphorus, and IDWG, while those not on K resin were older, more frequently had residual kidney function, more frequently dialyzed via catheter, had higher white blood cell count, higher dialysate K, and had higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, diabetes, and GI bleed.

Laboratory values and IDWG

In the adjusted linear mixed models, patients prescribed a K resin had greater IDWG, and higher serum K, bicarbonate, phosphorus, and Na (but not Ca) concentrations than patients without a K resin prescription (Table 2). The estimate for association of K resin use with serum K showed higher serum K in the standard adjusted model (+0.20 mEq/L, 95% confidence interval [CI]: +0.16, +0.24) and lower serum K in the instrumental variable analysis (−0.19 mEq/L, 95% CI: −0.37, 0.00). In contrast to serum K, the results for IDWG, serum bicarbonate, phosphorus, and Na were qualitatively consistent from the standard to instrumental variable analysis. For instance, serum phosphorus was 0.20 mg/dL higher (95% CI: +0.11, +0.29) for patients prescribed K resin versus patients not prescribed K resin in the standard adjusted model and 0.29 mg/dL higher (95% CI: −0.07, +0.65) in the instrumental variable analysis (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses excluding the minority of patients whose prescriptions specified “as needed” usage, rather than regularly scheduled dosing, yielded only trivial changes in the associations with serum electrolyte concentrations or IDWG.

Table 2. Associations of K Resin Prescription with Serum Chemistries and IDWG.

| Outcome | Crude model* | Adjusted model | Instrumental variable approach (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDWG (kg) | 0.46 (0.40,0.53) | 0.24 (0.18,0.30) | 0.19 (−0.10,0.49) |

| Serum Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 0.08 (−0.10,0.26) | 0.31 (0.12,0.50) | 0.06 (−1.01,1.13) |

| Serum Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 0.38 (0.30,0.47) | 0.20 (0.11,0.29) | 0.29 (−0.07,0.65) |

| Serum Potassium (mEq/L) | 0.37 (0.33,0.41) | 0.20 (0.16,0.24) | −0.19 (−0.37,0.00) |

| Serum Calcium (mg/dL) | 0.08 (0.04,0.13) | −0.01 (−0.06,0.03) | −0.05 (−0.25,0.15) |

| Serum Sodium (mEq/L) | 0.38 (0.20,0.55) | 0.32 (0.14,0.49) | 0.95 (0.01,1.90) |

Linear mixed models: Estimate (95% CI) is the difference in outcome for patients with K resin prescription versus no K resin prescription. IDWG=Interdialytic weight gain. Models adjusted for DOPPS phase, country, age, gender, black race, vintage, body mass index, residual kidney function, HD vascular access type, serum ferritin, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, serum albumin, serum creatinine, dialysate K, and 14 comorbid conditions (Table 1).

Crude model accounting for facility clustering effects and adjusted for DOPPS phase and country

Phosphate binder use

Forty-three percent of patients were prescribed a Ca and/or Mg based PB only, 14% were prescribed a Ca and/or Mg based PB plus additional type(s) of PB, 23% were prescribed another type of PB (not Ca or Mg based, primarily sevelamer), and 20% were not prescribed a PB. In an adjusted multinomial model (Table 3), patients prescribed K resin (versus not prescribed K resin) were significantly more likely to also be prescribed a Ca and/or Mg based PB only (odds ratio [OR] = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12-1.53), more likely to be prescribed a Ca and/or Mg based PB plus additional type of PB (OR=2.01, 95% CI: 1.68-2.40), and also more likely to be prescribed another type of PB (OR=1.51, 95% CI: 1.28-1.79), compared to the outcome reference group of patients not prescribed any PB. While K resin use was strongly associated with PB use, no evidence of interaction was found between K resin use and PB use in any of the adjusted models displayed in Table 2 (p > 0.05).

Table 3. Associations of K Resin Prescription with Various Types of Phosphate Binder (PB) Prescription.

| Outcome | Crude model* | Adjusted model |

|---|---|---|

| Ca and/or Mg based PB only | 1.59 (1.37-1.84) | 1.31 (1.12-1.53) |

| Ca and/or Mg based PB plus other type of PB | 3.14 (2.66-3.72) | 2.01 (1.68-2.40) |

| Any other type of PB (non Ca/Mg based) | 2.29 (1.96-2.69) | 1.51 (1.28-1.79) |

Multinomial logistic regression: Odds Ratio (95% CI) of the association of K resin prescription versus no K resin prescription. PB use category was treated as the outcome, with patients not prescribed any PB as the reference category. Models adjusted for DOPPS phase, country, age, gender, black race, vintage, body mass index, residual kidney function, HD vascular access type, serum ferritin, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, serum albumin, serum creatinine, dialysate K, and 14 comorbid conditions (Table 1).

Crude model adjusted for DOPPS phase and country

Mortality

Patients were followed for a maximum of 43.5 months (median=18.5 months, interquartile range=9.3-28.0 months). 2,861 (25%) patients died (mortality rate = 0.16 per patient-year). Although K resin prescription was associated with lower mortality in minimally adjusted analyses (Figure 2, Models 1-3), this was likely the result of residual confounding. Further adjustment for laboratory values attenuated this relationship, as Model 4 does not show a benefit for K resin prescription versus no K resin prescription (hazard ratio [HR]=0.97, 95% CI: 0.87-1.07). Furthermore, in an instrumental variable analysis intended to help account for this residual patient-level confounding, HR=1.08 (95% CI: 0.76-1.54).

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis of higher IDWG, higher serum levels of Na, phosphate, and bicarbonate in HD patients using a Na-based K resin is largely confirmed in this study. The effect sizes of the associations between K resin prescription and outcomes were moderate (Table 2) but remained after extensive adjustment for potential confounders. These observed trends are also confirmed with the instrumental variable approach, except for K. This finding is as predicted: the K results in the standard analysis likely reflect confounding by indication because patients with higher serum K concentration are prescribed a K resin more frequently. The instrumental variable approach is less prone to bias from unmeasured patient-level confounders (including confounding by indication) and thus may clarify the actual effect of the drug. The instrumental variable analysis showed that patients prescribed a K resin tended to have lower serum K with borderline statistical significance (p = 0.05). In a bias vs. precision trade-off, instrumental variable analyses provided benefits in handling unmeasured confounding at the cost of less precision than standard regression techniques [17], thus, we believe it is appropriate to focus more on the direction of the effect rather than the exact p-value. Although their impact could not formally be tested due to the small number of users of a Ca-based resin in the DOPPS, it should be mentioned that, despite a nutritional profile similar to users of Na-based resin, these patients had similar P and bicarbonate levels and slightly lower Na levels than patients not using resins (data not shown), opposite to the effects observed with Na-based K resins in dogs and as observed in the present DOPPS cohort [3]. IDWG was somewhat higher in Ca-based resin users than in non-users, although slightly lower than in Na-based resin users. This finding is in line with the mechanism of action of the respective resins within the gut.

K resin prescription is associated with an additional 250 g of IDWG in the adjusted model, likely to result from the Na content of the Na-based resin increasing thirst and fluid consumption. The impact of Na-based K resin therapy on serum phosphate concentration may seem moderate: around 0.2-0.3 mg/dL. However, as compared with placebo, the intake of 3-6 tablets per day of a Ca-based PB reduces phosphatemia by only approximately 0.9 mg/dL [18]. Patients prescribed a Na-based K resin not only had higher phosphate levels but were also more likely to be prescribed a PB, and especially likely to be prescribed multiple PBs, even after multivariable adjustment including nutritional parameters. These observations are consistent with van Ypersele’s thesis that Na-based K resins lead to increased phosphorus absorption in the gut, based on his dog studies [3]. The use of Na-based K resins also may drive increased PB prescription and may have pharmaco-economic implications.

The present study is the first to assess the association of resin use with mortality in a large sample of HD patients. The fully adjusted models do not suggest a benefit or a concern; survival was very similar with versus without K resin use after thorough multivariable adjustment, consistent with the instrumental variable findings. Surprisingly, not a single large observational study has been devoted to K resins and associated laboratory or clinical outcomes. The very infrequent use of K resins in some countries, including the US, likely results at least partly from concerns related to the risk of colonic necrosis under Kayexalate mixed with 70% sorbitol [4-5], the hitherto usual preparation in the US. In our study, the uncommon occurrence of colonic surgery of any type, including colectomy, was no higher among the K resin treated patients (0.6%) than among the others (1.0%), but the DOPPS questionnaires did not record events of colonic perforation specifically. It should also be noted that K resins were approved in the US by the Food and Drug Administration decades ago on the basis of efficacy data that today would not be considered convincing or lead to approval.

In fact, the effectiveness of K resins as a strategy to reduce K levels in dialysis patients has been a matter of recent debate in the nephrology literature [4, 5, 19]. Although many European nephrologists appear to be convinced of effectiveness as shown by their prescription pattern, uncertainty regarding safety and/or effectiveness probably accounts for part of the huge variability in K resin use between units and countries (Figure 1).

The strengths of the present study include the large sample size, and the availability of data on drug treatment and on many potential confounding factors in the detailed DOPPS prospective database, allowing for extensive multivariable adjustment. In addition, the DOPPS identified five countries with sufficiently high prescription rates of K resin to permit appropriate analyses.

Our study has several limitations. Due to the observational design of the DOPPS, the reported associations cannot be deemed proof of causality. In particular, patients with a K resin prescription may not comply with dietary prescriptions, leading to higher K and phosphorus levels and IDWG. However the higher bicarbonate level argues against this possibility, as greater intake of proteins is expected to lower bicarbonate level. In addition, multivariable analyses were adjusted for nutritional markers. The data collection did not include questionnaires regarding dietary intake of Na, K, phosphorus and fluid. However, the analyses were adjusted for nutritional markers and residual kidney function. Regarding the instrumental variable analyses, any violation of the assumptions may result in biased estimates. To avoid bias due to a weak instrument, the F-statistic should be greater than 10, and in our analysis the stage 1 F-statistic was 11.5 for K resin and 18.3 for dialysate K. Finally the design of the study does not answer the question of the balance between the potential benefit of K resin use as a way to liberalize food intake and thus improve nutrition versus the metabolic and IDWG potential drawbacks of resins.

In conclusion, prescription of a Na-based K resin was associated with higher IDWG, and higher serum Na, phosphorus, and bicarbonate levels, in HD patients in five European countries. In addition, Na-based resins likely reduce serum K concentrations in HD patients. The use of Na-based K resins was not associated with mortality. Half a century following the introduction of K resins into clinical practice, a well-powered, randomized, controlled trial of their effectiveness and safety to treat hyperkalemia in HD patients is still lacking. The dramatic variability we found in prescribing patterns across HD facilities and across nations indicates that such studies could greatly inform best practices.

Acknowledgments

Support and Financial Disclosure Statement:

The DOPPS program is supported by Amgen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, AbbVie Inc., Sanofi Renal, Baxter Healthcare, Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma, Ltd, and Fresenius Medical Care. Additional support for specific projects and countries is also provided in Canada by Amgen, BHC Medical, Janssen, Takeda, Kidney Foundation of Canada (for logistics support); in Germany by Hexal, DGfN, Shire, WiNe Institute; for PDOPPS in Japan by the Japanese Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (JSPD). All support is provided without restrictions on publications.

Prof. Jadoul has received speaker fees from Fresenius Medical Care Pharma, that markets Sorbisterit, a Calcium-based K Resin. Dr. Tentori is supported in part by Award Number K01DK087762 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tentori has received honoraria from Amgen and Dialysis Clinic Inc. Dr. Robinson has received speaker fees for Kyowa Hakko Kirin. Dr. Goodkin has consulted for Allocure, Alnylam, Baxter, ChemoCentryx, FibroGen, Isis, Rakth Therapeutics, and Xenon. He holds Xenon stock options.

References

- 1.Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111–115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196101192640302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherr L, Ogden DA, Mead AW, Spritz N, Rubin AL. Management of hyperkalemia with a cation-exchange resin. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:115–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196101192640303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Ypersele de Strihou C. Importance of endogenous acid production in the regulation of acid-base equilibrium : the role of the digestive tract. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1980;9:367–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1723–1726. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion- Exchange Resins for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia: Are They Safe and Effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:733–735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young EW, Goodkin DA, Mapes DL, et al. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study: an international hemodialysis study. Kidney Int. 2000;57:S74–S81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisoni RL, Gillespie BW, Dickinson DM, Chen K, Kutner MH, Wolfe RA. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): design, data elements, and methodology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(Suppl 2):7–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:444–455. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wooldridge J. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. 4th Edition South-Western College Pub; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ. 2008 May;27(3):531–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai B, Hennessy S, Flory JH, et al. Simulation study of instrumental variable approaches with an application to a study of the antidiabetic effect of bezafibrate. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 2):114–20. doi: 10.1002/pds.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Briesacher BA. Use of instrumental variable in prescription drug research with observational data: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(6):687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart BC, Doshi JA, Terza JV. Assessing the impact of drug use on hospital costs. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):128–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovesdy CP, Regidor DL, Mehrotra R, et al. Serum and dialysate potassium concentrations and survival in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(5):999–1007. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04451206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IVEware: Imputation and variance estimation software. Survey Methodology Program, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Raghunathan T.E., Solenberger P.W., Van Hoewyk J.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconomics Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press; 2005. p. 103. Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonelli M, Pannu N, Manns B. Oral phosphate binders in patients with kidney failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1312–1234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamel KS, Schreiber M. Asking the question again: are cation exchange resins effective for the treatment of hyperkalemia? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012 Dec;27(12):4294–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]