Abstract

Objective

To examine whether medical decisions regarding evaluation and management of musculoskeletal pain conditions varied systematically by characteristics of the patient or provider.

Methods

We conducted a balanced factorial experiment among primary care physicians in the U.S. Physicians (N=192) viewed two videos of different patients (actors) presenting with pain: (1) undiagnosed sciatica symptoms or (2) diagnosed knee osteoarthritis. Systematic variations in patient gender, socioeconomic status (SES), race, physician gender and experience (<20 vs. ≥20 years in practice) permitted estimation of unconfounded effects. Analysis of variance was used to evaluate associations between patient or provider attributes and clinical decisions. Quality of decisions was defined based on the current recommendations of the ACR, American Pain Society, and clinical expert consensus.

Results

Despite current recommendations, under one-third of physicians would provide exercise advice (30.2% for osteoarthritis, 32.8% for sciatica). Physicians with fewer years in practice were more likely to provide advice on lifestyle changes, particularly exercise (P<0.01), and to prescribe NSAIDs for pain relief, both of which were appropriate and consistent with current recommendations for care. Newer physicians ordered fewer tests, particularly basic laboratory investigations or urinalysis. Test ordering decreased as organizational emphasis on business or profits increased. Patient factors and physician gender had no consistent effects on pain evaluation or treatment.

Conclusion

Physician education on disease management recommendations regarding exercise and analgesics, and implementation of quality measures may be useful, particularly for physicians with more years in practice.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has called for more aggressive treatment of pain, including arthritis and musculoskeletal pain (1). However, pain management is complicated by factors such as the potential toxicity of NSAIDs or the risk of abuse and diversion of opioids (2). Furthermore, the scientific understanding of pain pathology is incomplete; definitive standards for pain management applicable to all patients with a given set of symptoms or diagnosis do not exist, reflecting the inconsistency and sparseness of the evidence-base. For example, for knee osteoarthritis, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 2012 provided “conditional recommendations” for most commonly used therapies (e.g., NSAIDs) and no recommendations for intraarticular hyaluronates, duloxetine, or opioid analgesics. “Strong recommendations” were given only for physical exercise (cardiovascular and/or resistance exercise) and weight loss (for persons who are overweight) (3).

Given limited clinical recommendations, it is not surprising that pain management decisions regarding opioids and other analgesics vary widely in practice (4-8). In particular, under-treatment of pain has been documented for women, blacks and Hispanics (9-11). Prescribing also reportedly varies by physician gender, specialty and litigation fears (12, 13). Where there are strong recommendations – e.g., for exercise for knee osteoarthritis (3) or remaining active for low back pain (14) – there should be minimal variation in physicians’ decision-making. Particularly in such cases, understanding the sources of variation (e.g., provider experience, patient race) is important to assess and promote quality of care. Currently, most studies on variations in pain management focus on narcotic prescribing, yet attention to actions regarding patient education and advice is also essential, given their beneficial effects on patient outcomes (15-19).

A difficulty with research attempting to identify extraneous factors in decision-making is that numerous intricately-related factors comprise patient presentations and physicians’ backgrounds. Observational research inevitably produces confounded estimates of these various influences. For example, patient race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) are strongly correlated in the U.S. (20, 21), and both have been associated with pain management (7, 22). The importance of disentangling their effects on pain care is that public health implications for policy changes and improvements in quality monitoring may be notably different if pain treatment decisions are influenced, for example, by educational level rather than race (5, 21, 23).

The objective of this analysis was to examine whether the quality of care regarding advice on exercise and weight loss, as well as decisions on imaging and analgesic prescribing, varied systematically by patient race, gender or SES, or by the clinical experience, gender, or work environment of the physician. In light of the intricate relationships among these variables, we conducted a factorial experiment that provides unconfounded effects of three patient factors (race/ethnicity, SES, gender), and two physician factors (gender, years of clinical experience) on the quality of clinical decisions regarding diagnosis and management of two common musculoskeletal conditions. Thus, we are able to examine the distinct influences and unique interactions of these patient and physician factors on quality of care. Given the lack of clinical guidelines for pain management, quality of care is pragmatically defined herein as clinically appropriate actions, based on the current recommendations of the ACR and American Pain Society; similar approaches have been shown to provide acceptable measures of quality in health care (24-26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study design was a balanced factorial experiment, which permits the estimation of unconfounded main effects and interactions of patient and provider factors that varied by design. Six factors varied by design: patient gender, race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, or white), socioeconomic status (lower or higher), and request for a particular pain medication (oxycodone or Celebrex; yes/no request); physician gender and years of clinical experience (<20 or >20 years since medical school graduation). In previous analyses, we presented findings that patient requests for medication influenced physician prescribing decisions, to comply with the request (27).

Physician Subjects

The experiment was conducted among practicing physicians identified from lists of licensed physicians in Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island. To be eligible, physicians (i) completed a medical residency program in internal medicine or family practice, (ii) were licensed as a primary care physician, and (iii) provided clinical care at least half-time. Primary care physicians were of interest because, as the gateway to treatment and referrals, their decisions determine the course for patient care and outcomes. During recruitment, physicians were classified according to gender and year of graduation from medical school (1970-1991 vs. 1992-2002, for a cut-point of approximately 20 years of clinical experience) and purposefully recruited until each combination needed for the factorial design was complete. Eligible physicians were telephoned and invited for in-person interviews to obtain written informed consent. Physicians were informed that the study was designed to examine how primary care doctors manage pain conditions. The study protocol was approved by the New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board.

Experimental Stimuli (Patient Scenarios)

Physicians were randomized to watch two vignettes, featuring two different patient presentations. One vignette presented an undiagnosed actor-patient discussing signs and symptoms strongly suggestive of sciatica (referred to as the “sciatica patient”). The other presented an actor-patient with previously diagnosed osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee (referred to as the “OA patient”), requiring ongoing case management. Details on the symptoms and complaints presented in each case are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Presentation Symptoms, Appropriate Treatment, and Inappropriate Treatment1

| Sciatica Patient | Knee Osteoarthritis Patient |

|---|---|

| Presentation | Presentation |

|

|

| Appropriate Treatment | Appropriate Treatment |

|

|

| Inappropriate | Inappropriate |

Appropriate and inappropriate outcomes for treatment or evaluation are for the specific patient case presented, as determined by the clinician authors (J.K., M.F.) and published recommendations of the American College of Rheumatology (2012), American College of Physicians, and American Pain Society (2007).

Current recommendations are that MRI should not be used routinely for back pain, but rather be reserved only for patient cases who are candidates for surgery or epidural steroid injections. Thus, in the case patient presenting with previously undiagnosed sciatica pain, it would be inappropriate to order an MRI at that time. For OA, current recommendations are that imaging should be reserved for instances in which the diagnosis is unclear, to refute other diagnoses that might have been confused with OA (e.g,. avascular necrosis) (52). For the OA patient case, the diagnosis was stated at the outset, and the physician’s task was pain management; therefore, an MRI would be difficult to justify.

In the current experiment, narcotics were inappropriate for both cases, particularly given that the patients’ occupations involved motor vehicle operation.

To create the patient presentations, six professional actors/actresses were trained to portray a patient presenting to a primary care doctor. Scripts for the scenarios of interest were developed from tape-recorded role-playing sessions with clinically-active physicians (including authors J.K. and M.F.). The scenario was repeatedly filmed, systematically changing the actor-patient’s race (black, Hispanic, white), gender, SES (lower vs. higher social class – a truck driver vs. sales representative for sciatica; a janitor vs. a lawyer for OA; also expressed by clothing style), and whether s/he requested a particular pain medication. Each video simulated an initial consultation with a primary care physician and was of 3-5 minutes in duration, reflecting the average length for initial history in an office consultation, without physical examination and without physician interruptions for questioning (28). Observation of the videos by other primary care providers confirmed their clinical authenticity.

Assessment of Medical Decision-Making

Immediately after the physician subjects viewed each vignette, trained study staff members conducted semi-structured interviewers, recording responses using predefined categories and open text fields. The data collected included a range of decisions as they relate to each clinical scenario, including the tests to be ordered, medication to be prescribed, referrals, and timeframe for next visit. Advice to be given to the patient (including exercise and weight loss) was obtained by asking “Would you advise the patient about lifestyle or behavior today?” with a follow-up question, “What would you advise for this patient today?”

There is no single “gold standard” for optimal treatment of these musculoskeletal conditions that could be used to strictly classify adherence to guidelines. The quality of decision-making was assessed using published clinical practice recommendations of the ACR for OA of the knee (3) and of the American College of Physicians and American Pain Society for low back pain (14). These clinical practice guidelines encapsulate a rigorous review of the published literature; thus, they are generally congruent with practice guidelines. We chose to base our assessments on practice guidelines rather than quality measurement tools because the latter often are a blend of published evidence and expert opinion. A summary of the recommendations, as they relate to the particular cases in this experiment, is provided in Table 1. Physicians were not informed of the operational definition of quality of care used in the experiment.

Covariate Assessment

After the interview, physicians completed a self-administered questionnaire on their personal background, medical training, practice setting, and use of clinical guidelines. Practice culture was measured by an abbreviated version of the standardized Medical Group Practice Culture Survey (29), which was designed for use among primary care physicians and has been shown to have predictive value in small and large group practice environments. It includes ten Likert-scaled items measuring nine cultural dimensions; of particular interest in this analysis of clinical decision-making were the dimensions of “business emphasis,” “information emphasis,” “quality emphasis,” and “organizational trust.” Satisfaction with career and current job were assessed using the global scales of the validated Physician Worklife Survey (30, 31).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was used to test the effects of the design variables on a range of diagnostic and treatment decisions. The balanced factorial design produced 3*22=12 patient sociodemographic characteristic (race, gender, SES) combinations. Each combination was portrayed twice to accommodate the drug request, yielding 24 distinct vignettes for each musculoskeletal condition. The two physician factors (gender, experience) create four strata. Within each stratum, 48 physician subjects were randomly assigned to view one of the 24 pairs of vignettes. In additional analyses, covariates (i.e., physician characteristics such as race/ethnicity, practice setting, and practice culture) were examined using logistic regression. A generalized coefficient of determination (R2) statistic was used to determine the proportion of variation in the outcome that was explained by the independent variables in the model. Due to the challenges of multiple testing, we emphasize consistency across results.

The total sample of 192 physicians provided 80% power at level 0.05 to detect an absolute difference in means of 0.2 standard deviations, which is considered a small effect size. For example, for analysis of physician gender and advising patients regarding exercise, if the rate of giving exercise advice were 0.25, the study is powered to detect a difference in proportions between male and female physicians of 0.09, which results in a gender difference in rates of providing exercise advice ranging from 0.16 (0.25−0.09) to 0.34 (0.25+0.09).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Physician Subjects

Of the 192 physicians randomized in this experiment, most (79.7%) worked in a shared office practice (median 4 staff physicians), and the average time at their current practice was 10.8 years. Twenty-two percent of physicians had been in practice >30 years, while 20.8% graduated within the past 10 years. The physicians’ ages ranged from 35-74 years, with mean (SD) 41.4 (4.5) years for physicians classified as having fewer years in practice, and mean (SD) 57.7 (5.7) years for physicians classified as more experienced. Similar proportions reported being in family practice (49.5%) or internal medicine (44.8%); the remaining 5.7% identified as general practitioners. Race/ethnicity varied, with 55.2% white, 24.5% Asian, 7.3% black, and 5.7% of Hispanic ethnicity. Only 7.3% reported that they generally do not use clinical guidelines in the management of patients. Sixty-five percent of physicians reported that their knowledge of guidelines affected their decision-making for the patient presentations at hand.

After viewing the video vignettes, 95% of the physicians reported the patient presentations viewed were typical of those seen in their everyday practice. The task of providing the most probable diagnosis for the sciatica patient was appropriately completed by most physicians: sciatica or a related condition (e.g., herniated disc) were listed as one of the possible diagnoses by 93.7% of physicians and were the most probable diagnosis of 64.1% of physicians.

Multivariable Model Results for Musculoskeletal Pain Management

(i) Physician Factors

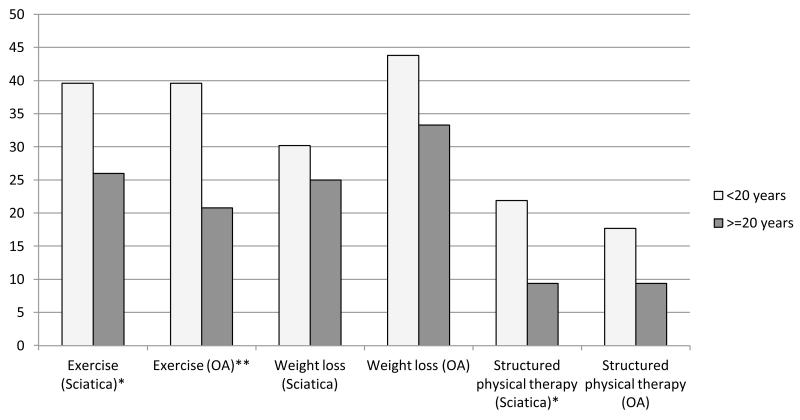

Physician gender was not associated with decisions for either patient scenario and had no statistically significant interactions with patient gender. In contrast, physician length of time in practice was associated with the quality of clinical decisions. Newer physicians were more likely to give advice on lifestyle behaviors (P=0.01), particularly regarding exercise habits (39.6% of newer physicians, vs. 26.0% of more experienced physicians for sciatica, or vs. 20.8% of more experienced physicians for OA). Results were similar for advice to lose weight and referrals for physical therapy (Figure 1). Additional analyses exploring the nature of the relationship indicated that there was a continuous linear inverse trend between length of time in practice and probability of giving such advice (P<0.01, data not shown). In addition, lifestyle advice for knee OA was twice as likely to be provided by physicians who worked in organizations with greater emphasis on quality of care (odds ratio=2.35, 95% CI 1.12-4.92, P=0.01). Other workplace culture values were not associated with lifestyle counseling.

Figure 1. Physician Experience (years in practice) and Appropriate Advice Given to the Pain Patient.

Columns represent the percentage of physicians that would provide advice on the particular topic for pain management, all of which are appropriate for the patient cases.

*P<0.05. **P<0.01.

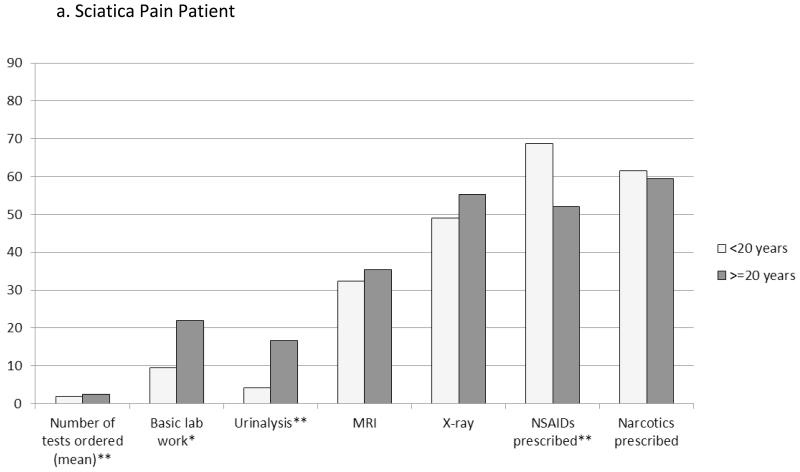

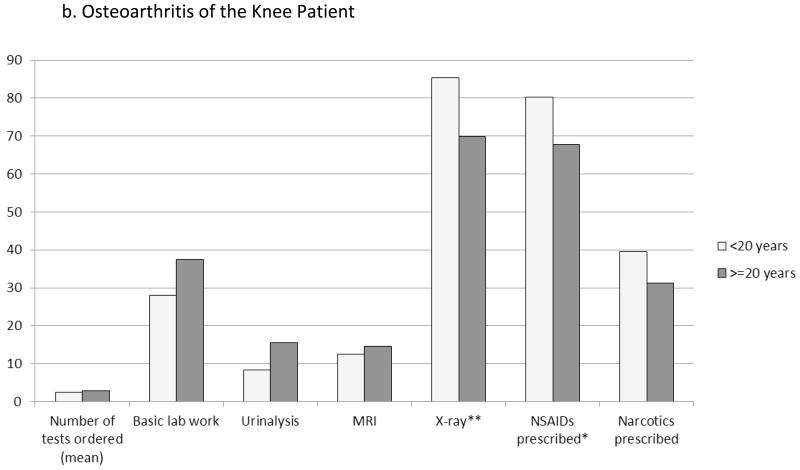

In addition to advice and referrals, analgesic prescribing and test ordering were associated with physicians’ years of experience and other provider characteristics (Figure 2). Newer physicians more commonly would prescribe NSAIDs for pain relief (68.8% vs. 52.1%, P=0.01 for sciatica patient; OA patient, 80.2% vs. 67.7%, P=0.02). The total number of tests ordered was, on average, slightly lower among newer physicians (sciatica, mean 1.9 vs. 2.5 tests, P=0.01; OA 2.4 vs. 2.9 tests, P=0.07), who less frequently would order basic lab work (e.g., complete blood count or metabolic panel, 9.4% vs. 21.9%, P=0.02) and urinalysis (4.2% vs. 16.7%, P=0.003), particularly for sciatica. For the OA patient only, X-rays were more often ordered by newer physicians (85.4% vs. 69.8%).

Figure 2. Effects of Physician Experience (years in practice) on Test Ordering and Analgesics Prescribed.

Columns represent the percentage of physicians that would order the particular test or prescribe the class of medications for the newly diagnosed pain patient; exception of the first column, which represents the mean total number of tests that the physicians would order. Basic lab work included complete blood count, basic metabolic/chemistry panel, and lipid profile tests. *P<0.05. **P<0.01.

In addition to years since training, physicians who received their medical degree in the U.S. (n=127, 66.1% of physician subjects) ordered fewer tests than did foreign medical school graduates (e.g., sciatica, mean ± SD 1.9 ± 1.4 tests, vs. 2.8 ± 1.8, P=0.003), particularly basic lab work (8.1% vs. 30.2%, P=0.002). Test ordering also decreased as the organizational emphasis on business decisions and profit maximization increased (P=0.02, OA patient); each unit increase in business emphasis score was associated with a 70% lower odds of test ordering. Similarly, physicians practicing in for-profit organizations were less likely to order any tests/labs, compared to physicians from non-profit organizations (91.4% vs. 100%, P=0.01, OA patient) (data not shown).

Although MRI is considered inappropriate for these patient scenarios, one-third of physicians (33.9%) would order MRI for the sciatica patient, and 13.5% would order MRI for the OA patient. For the OA patient only, MRI use was more frequent among physicians who generally do not use clinical guidelines in the management of their patients (21.4% vs. 12.9%, P=0.04). No associations were found between physician job or career satisfaction, payment structure (e.g., paid by salary or productivity), practice type (family practitioner, general practitioner, or internal medicine), practice size, or race/ethnicity and any of the decision outcomes (data not shown).

(ii) Patient Factors

Overall, evaluation and treatment plans showed no consistent variation by patient factors (Table 2). Muscle relaxants were more commonly prescribed to women, and basic lab work was ordered more often for men with sciatica pain. Patient SES was associated with type of pain medication prescribed for the sciatica patient: narcotic medications (considered inappropriate for these scenarios) were more commonly chosen for patients of higher SES (68.7% vs. 52.1%, P=0.01), whereas NSAIDs, which are more appropriate, were more commonly mentioned for patients of lower SES (67.7% vs. 53.1%, P=0.03). This effect of patient SES was not observed for the OA patient. However, race was associated with narcotic prescription for OA patients: narcotics were prescribed to white patients more (46.9%) than Hispanic (32.8%) or black (26.6%) patients (P=0.03). The only other racial/ethnic difference was testing for OA: 87.6% of Hispanic patients would receive any laboratory testing or imaging, compared to 100% of white and 96.9% of black patients (P=0.01).

Table 2.

Variations in Evaluation and Treatment Decisions, by Patient Characteristics (Gender, Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status)1

| Patient Gender | Patient Race/Ethnicity | Patient Socioeconomic Status |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Sciatica Pain | Female | Male | P | Black | Hispanic | White | P | Lower | Higher | P |

| Counseling/Education | ||||||||||

| Exercise | 36.5 | 29.2 | 0.3 | 29.7 | 43.8 | 25.0 | 0.07 | 33.3 | 32.3 | 0.9 |

| Avoid bending, lifting, etc. |

28.1 | 30.2 | 0.8 | 23.4 | 35.9 | 28.1 | 0.3 | 30.2 | 28.1 | 0.8 |

| Ergonomics | 17.7 | 20.8 | 0.6 | 20.3 | 15.6 | 21.9 | 0.7 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 0.9 |

| Increase rest | 15.6 | 17.7 | 0.7 | 17.2 | 12.5 | 20.3 | 0.5 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 1.0 |

| Physical therapy | 14.6 | 16.7 | 0.7 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 18.8 | 0.7 | 16.7 | 14.6 | 0.7 |

| Medications | ||||||||||

| Narcotics | 63.5 | 57.3 | 0.3 | 70.3 | 56.3 | 54.7 | 0.10 | 52.1 | 68.7 | 0.01 |

| NSAIDs2 | 59.4 | 61.5 | 0.8 | 54.7 | 60.9 | 65.6 | 0.4 | 67.7 | 53.1 | 0.03 |

| Muscle relaxants | 57.3 | 36.5 | 0.002 | 46.9 | 40.6 | 53.1 | 0.3 | 52.1 | 41.7 | 0.12 |

| Order tests/labs | 64.6 | 77.1 | 0.05 | 78.1 | 71.9 | 62.5 | 0.14 | 72.9 | 68.8 | 0.5 |

| No. tests ordered3 | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.7 | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.7 (2.0) | 0.13 | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.5) | 0.7 |

| Basic lab work4 | 10.4 | 20.8 | 0.04 | 14.1 | 12.5 | 20.3 | 0.4 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 1.0 |

| X-ray | 50.0 | 54.2 | 0.5 | 59.4 | 50.0 | 46.9 | 0.3 | 55.2 | 49.0 | 0.4 |

| MRI | 29.2 | 38.5 | 0.2 | 32.8 | 40.6 | 28.1 | 0.4 | 32.3 | 35.4 | 0.7 |

| Urinalysis | 9.4 | 11.5 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 0.05 | 12.5 | 8.3 | 0.3 |

| Knee Osteoarthritis | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Counseling/Education | ||||||||||

| Exercise | 30.2 | 30.2 | 1.0 | 26.6 | 28.1 | 35.9 | 0.5 | 25.0 | 35.4 | 0.12 |

| Avoid bending, lifting, etc. |

12.5 | 7.3 | 0.3 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 0.2 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 0.8 |

| Continue normal physical activity |

10.4 | 17.7 | 0.16 | 12.5 | 20.3 | 9.4 | 0.2 | 15.6 | 12.5 | 0.6 |

| Increase rest | 11.5 | 8.3 | 0.5 | 9.4 | 12.5 | 7.8 | 0.7 | 8.3 | 11.5 | 0.5 |

| Physical therapy | 14.6 | 12.5 | 0.7 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15.6 | 0.8 | 14.6 | 12.5 | 0.7 |

| Medications | ||||||||||

| Narcotics | 39.6 | 31.2 | 0.2 | 26.6 | 32.8 | 46.9 | 0.03 | 40.6 | 30.2 | 0.11 |

| NSAIDs2 | 79.2 | 68.8 | 0.07 | 78.1 | 70.3 | 73.4 | 0.5 | 70.8 | 77.1 | 0.3 |

| Order tests/labs | 94.8 | 94.8 | 1.0 | 96.9 | 87.6 | 100.0 | 0.01 | 93.8 | 95.8 | 0.5 |

| No. tests ordered3 | 2.7 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.9) | 0.04 | 2.8(1.9) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.6 (1.9) | 0.9 | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.6 (2.0) | 0.8 |

| Basic lab work4 | 35.4 | 30.2 | 0.4 | 39.1 | 25.0 | 34.4 | 0.3 | 32.3 | 33.3 | 0.9 |

| MRI | 13.5 | 13.5 | 1.0 | 18.8 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 0.3 | 15.6 | 11.5 | 0.4 |

| X-ray | 77.1 | 78.1 | 0.9 | 79.7 | 70.3 | 82.8 | 0.2 | 75.0 | 80.2 | 0.4 |

| Sed rate | 24.0 | 20.8 | 0.6 | 25.0 | 17.2 | 25.0 | 0.5 | 25.0 | 19.8 | 0.4 |

| CRP | 14.6 | 11.5 | 0.6 | 12.5 | 9.4 | 17.2 | 0.5 | 15.6 | 10.4 | 0.3 |

| Urinalysis | 7.3 | 16.7 | 0.06 | 6.3 | 17.2 | 12.5 | 0.2 | 10.4 | 13.5 | 0.5 |

All results were obtained from multivariable models mutually adjusting for the patient and physician factors. The table lists treatment plan components that were mentioned by at least 10% of physicians. Numbers are the percent of patients who received the specified action/treatment decision. Sed rate=sedimentation rate; CRP=C-reactive protein.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) include COX-2 inhibitors, naproxen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, diclofenac, acetic acid NSAIDs, propionic acid NSAIDs, oxicam NSAIDs, and prioxicam.

Mean (SD)

Basic lab work included complete blood count, basic metabolic/chemistry panel, and lipid profile tests.

(iii) Overall Contributions of Patient and Provider Variables

We evaluated the total contribution of patient (gender, race, SES, medication request) and provider (gender, experience) design factors, together with personal (race, medical school training, guideline use, job and career satisfaction) and organizational characteristics (profit/nonprofit; % managed care; practice culture emphasis on business, quality, information, and trust) in explaining variation in decision-making. Results showed that the decision to provide exercise advice remained largely unexplained even after accounting for these various factors; 13.4% of the variation was explained by these factors for the OA patient and 19.9% for the sciatica patient. Similarly, for test ordering, 12.9% (OA) and 21.1% (sciatica), and for narcotic medication prescribing, 13.7% (OA) and 13.9% (sciatica) of the variation in decision-making was explained by these factors.

DISCUSSION

This health services factorial experiment found considerable variation in decision-making for painful musculoskeletal conditions, yet little of this variation was explained by patient factors of race, SES, or gender. Rather, two factors that most consistently affected the quality of treatment decisions were (1) the physicians’ years in practice, whereby newer physicians more often followed clinical practice recommendations to provide exercise advice, or prescribed NSAIDs for pain relief, which was appropriate for the case patients, and (2) organizational values, whereby emphasis on quality of care was associated with providing lifestyle advice. These findings indicate that adherence to current clinical practice recommendations for musculoskeletal pain patients is more likely to occur among newer physicians, regardless of patient characteristics, and that certain organizational practice cultures may influence pain care.

The possibility that newer physicians are more up-to-date on recommendations or guidelines from medical societies is consistent with prior studies (32-34). In our experiment, physicians’ years in practice had effects on patient counseling, prescribing, and test ordering. Newer physicians were almost twice as likely to give lifestyle advice, particularly exercise, to the OA patient. Currently, exercise (cardiovascular or resistance) is the only “strong recommendation” for knee OA treatment from the ACR (3). This difference may represent a cohort effect during medical training. For low back pain, advice to “remain active” became accepted in the last two decades, replacing common earlier beliefs on need for bed rest (14, 15). Similarly, our finding that newer physicians more commonly prescribed NSAIDs supports the possibility that newer physicians may be more aware of and/or more inclined to follow recommendations; oral and topical NSAIDs were “conditionally recommended” for use for knee OA and considered as “first-line medication options” for low back pain (14).

Of note, one in three physicians would order an MRI for the sciatica patient. Use of MRI for either patient case contrasts with current evidence-based recommendations (14). Overuse of MRI has been a prominent concern in the medical community, for reasons including (i) lack of evidence of improved outcomes, (ii) identification of abnormalities that are uncorrelated with symptoms, and (iii) the possibility of leading to additional unnecessary interventions and healthcare costs (14). We found that MRIs for knee OA were more frequently ordered by physicians who reported that they generally do not use clinical guidelines for patient management. Also, the total number of ordered tests was lower among newer physicians and among U.S. medical school trained vs. foreign trained physicians. A speculative explanation for these findings is that a greater concern for cost control and adherence to society recommendations leads to ordering of fewer tests. The inverse association between organizational cultures emphasizing business profits and test-ordering also suggests that cost of care was considered. Interpretation of these results is problematic, because the absolute number of tests ordered is not a definitive quality outcome measure. For example, we found that organizational culture emphasizing quality of care was not associated with test ordering, yet was associated with providing lifestyle advice. Such associations between practice culture and pain management decisions are similar to findings from other therapeutic areas (35, 36), but studies on pain care are lacking. Additional quantitative and qualitative research is needed to explore test ordering and the resulting implications on quality and costs of healthcare.

Prior research suggested the importance of patient race, SES, and provider gender in pain management, such as the receipt of narcotics (37). In an earlier experiment using written patient vignettes among emergency room physicians, patient SES had a slight effect on narcotic prescriptions, whereas race/ethnicity had no effect (5). In our experiment, narcotics were inappropriate for both cases, particularly given that the patients’ occupations involved motor vehicle operation. Subjects with sciatica and lower SES had a lower likelihood of receiving a narcotic medication, and greater likelihood of receiving NSAIDs than those with higher SES. The same SES effect was not observed for the OA patient; rather, a lower percentage of blacks and Hispanics, compared to whites, received narcotics. Because the same physicians viewed both scenarios, it is possible that race and SES influence depend on the type of pain presented, but additional research is warranted.

This experiment’s use of video-vignettes offers distinct advantages over observational studies and previous written-vignette experiments: allowing manipulation of factors, strict standardization, inclusion of non-verbal cues, and inclusion of socio-emotional components alongside complex symptom presentations (38-40). A unique experimental factor in this study was the patient’s request for a particular pain medication. Indeed, the patient request influenced pain management, including receipt of that particular medication or others in its class (27). Despite this influence, there were no consistent interactions with patient request and the factors of interest in the current analysis, and the current findings were robust to consideration of the patient request.

Although the experimental study design and standardized patient scenarios help to maintain internal validity of this study, a limitation is that generalizability is hampered because actual interactions between the doctor and the patient were lacking. For decisions that are partly based on patient preferences, the quality of the doctor-patient communication is important. For example, for NSAID use, an interactive explanation of risks and benefits, tempered by patients’ preferences and values, would allow an ideal scenario for evaluating quality of care. Also, the study did not simulate a physical examination or allow further questioning, which in the actual clinical setting may influence decisions. However, observational clinical studies are unable to clearly identify which are the key contributors to clinical decision-making, and it is logistically difficult, burdensome and often unethical to use real patients in such research. Thus clinical scenarios are commonly used by medical educators, health services researchers, and in training efforts to improve quality of care (41-49).

In summary, this experiment found variation in the quality of musculoskeletal pain management decisions, particularly to provide exercise and other lifestyle advice, associated with physicians’ years in practice and organizational cultural values. Generally, newer physicians had greater adherence to current recommendations. Unlike prior studies, characteristics of patients in terms of race, SES, and gender had no consistent effects. It is possible that racial distinctions have diminished over time, but additional research on physicians’ cognitive processes during interactions with patients is warranted. Also, it remains uncertain whether results on musculoskeletal pain decision-making apply to patient presentations where clearly defined clinical practice guidelines document right and wrong actions. These findings highlight key areas of clinical practice recommendations that primary care physicians – who often shape the patient’s entire course of pain management – are prone to neglect, particularly regarding exercise advice, narcotic prescribing, and imaging.

Overall, the observed variations in decision-making were still largely unexplained even after accounting for all the patient, provider, and organizational variables that were statistically significant in the multivariable models. The frequency with which physicians made recommendations not supported by current evidence-based recommendations supports prior calls for improved physician education or other interventions that may lead to changes in practice (50-52). Methods to more effectively disseminate current recommendations for diagnosis and management of pain conditions should be developed and tested to improve the quality of care for these common clinical problems.

SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATIONS.

Using a randomized factorial experiment, the authors obtained unconfounded estimates of the impact of physician clinical experience and gender, and patient gender, race, and socioeconomic status on decisions regarding the evaluation and management of two musculoskeletal pain presentations (osteoarthritis of the knee or low back pain suggestive of sciatica).

Physicians who more recently completed their medical training were almost twice as likely to provide the patient advice regarding exercise or physical activity, as is currently recommended for knee case patients.

Patient gender, race, or socioeconomic status, and physician gender were not consistently associated with the quality of clinical decisions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This paper was supported by Award Number AR056992 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders (NIAMS), National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures or Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Fischer has received research support from CVS-Caremark for studies of medication adherence. All other authors attest that they have no financial interest conflicting with complete and accurate reporting of the study findings.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pizzo PA, Clark NM. Alleviating suffering 101--pain relief in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(3):197–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis care & research. 2012;64(4):465–74. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green CR, Wheeler JR, LaPorte F. Clinical decision making in pain management: Contributions of physician and patient characteristics to variations in practice. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2003;4(1):29–39. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Albert JM, et al. The effect of race/ethnicity and desirable social characteristics on physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioid analgesics. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10(11):1239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Dominguez RE. The influence of gender and race on physicians’ pain management decisions. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2003;4(9):505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cintron A, Morrison RS. Pain and ethnicity in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of palliative medicine. 2006;9(6):1454–73. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess DJ, Crowley-Matoka M, Phelan S, Dovidio JF, Kerns R, Roth C, et al. Patient race and physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic low back pain. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(11):1852–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, et al. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass. 2003;4(3):277–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T. The adequacy of chronic pain management prior to presenting at a tertiary care pain center: the role of patient socio-demographic characteristics. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11(8):746–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, Crowley-Matoka M, Malat J. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass. 2006;7(2):119–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. Southern Medical Journal. 2010;103(8):738–47. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e74ede. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Jr., Shekelle P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(7):478–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, Hagen KB. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010;(6):CD007612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007612.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2007;66(4):433–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albert HB, Manniche C. The efficacy of systematic active conservative treatment for patients with severe sciatica: a single-blind, randomized, clinical, controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(7):531–42. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821ace7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2008;(4):CD004376. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Does land-based exercise reduce pain and disability associated with hip osteoarthritis? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2010;18(5):613–20. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louie GH, Ward MM. Socioeconomic and ethnic differences in disease burden and disparities in physical function in older adults. American journal of public health. 2011;101(7):1322–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.199455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinlay JB, Marceau LD, Piccolo RJ. Do doctors contribute to the social patterning of disease? The case of race/ethnic disparities in diabetes mellitus. Medical Care Research and Review. 2012;69(2):176–93. doi: 10.1177/1077558711429010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11(11):1230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maserejian NN, McKinlay JB. Demographic characteristics and opioid prescribing. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(15):1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.15.1773-a. author reply 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ (Clinical research. 2003;326(7393):816–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Jain S, Hansen J, Spell M, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141(10):771–80. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peabody JW, Tozija F, Munoz JA, Nordyke RJ, Luck J. Using vignettes to compare the quality of clinical care variation in economically divergent countries. Health Services Research. 2004;39(6 Pt 2):1951–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKinlay J, Trachtenberg F, Marceau L, Katz JN, Fischer M. The effects of a patient medication request on physician prescribing behavior: Results of a factorial experiment; AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (ARM); Baltimore, MD. 2013; Jun 23, 2013. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhoades DR, McFarland KF, Finch WH, Johnson AO. Speaking and interruptions during primary care office visits. Family medicine. 2001;33(7):528–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kralewski J, Dowd BE, Kaissi A, Curoe A, Rockwood T. Measuring the culture of medical group practices. Health Care Management Review. 2005;30(3):184–93. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, et al. Physician, practice, and patient characteristics related to primary care physician physical and mental health: results from the Physician Worklife Study. Health Services Research. 2002;37(1):121–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, et al. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. Society of General Internal Medicine. Medical Care. 1999;37(11):1140–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;142(4):260–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elstad EA, Lutfey KE, Marceau LD, Campbell SM, von dem Knesebeck O, McKinlay JB. What do physicians gain (and lose) with experience? Qualitative results from a cross-national study of diabetes. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(11):1728–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenny SJ, Smith PJ, Goldschmid MG, Newman JM, Herman WH. Survey of physician practice behaviors related to diabetes mellitus in the U.S. Physician adherence to consensus recommendations. Diabetes care. 1993;16(11):1507–10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.11.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaissi A, Kralewski J, Curoe A, Dowd B, Silversmith J. How does the culture of medical group practices influence the types of programs used to assure quality of care? Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(2):129–38. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shackelton R, Link C, Marceau L, McKinlay J. Does the culture of a medical practice affect the clinical management of diabetes by primary care providers? Journal of health services research & policy. 2009;14(2):96–103. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department analgesic prescription. American journal of public health. 2003;93(12):2067–73. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinlay JB, Potter DA, Feldman HA. Non-medical influences on medical decision-making. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42(5):769–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman HA, McKinlay JB, Potter DA, Freund KM, Burns RB, Moskowitz MA, et al. Nonmedical influences on medical decision making: an experimental technique using videotapes, factorial design, and survey sampling. Health Services Research. 1997;32(3):343–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marceau L, McKinlay J, Shackelton R, Link C. The relative contribution of patient, provider and organizational influences to the appropriate diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2011;17:1122–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinsky LE, Wipf JE. A picture is worth a thousand words: practical use of videotape in teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(11):805–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hulsman RL, Mollema ED, Oort FJ, Hoos AM, de Haes JC. Using standardized video cases for assessment of medical communication skills: reliability of an objective structured video examination by computer. Patient education and counseling. 2006;60(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalet AL, Mukherjee D, Felix K, Steinberg SE, Nachbar M, Lee A, et al. Can a web-based curriculum improve students’ knowledge of, and attitudes about, the interpreted medical interview? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):929–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rainville J, Carlson N, Polatin P, Gatchel RJ, Indahl A. Exploration of physicians’ recommendations for activities in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(17):2210–20. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200009010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nampiaparampil DE, Nampiaparampil JX, Harden RN. Pain and prejudice. Pain Med. 2009;10(4):716–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Physician judgments of chronic pain patients. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedson J, Jordan K, Croft P. How do GPs use x rays to manage chronic knee pain in the elderly? A case study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003;62(5):450–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchinson AR, Kerr EA, Krein SL. Management of chronic noncancer pain by VA primary care providers: when is pain control a priority? The American journal of managed care. 2008;14(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagerlov P, Loeb M, Andrew M, Hjortdahl P. Improving doctors’ prescribing behaviour through reflection on guidelines and prescription feedback: a randomised controlled study. Quality in Health Care: QHC. 2000;9(3):159–65. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feuerstein M, Hartzell M, Rogers HL, Marcus SC. Evidence-based practice for acute low back pain in primary care: patient outcomes and cost of care. Pain. 2006;124(1-2):140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunter DJ, Neogi T, Hochberg MC. Quality of osteoarthritis management and the need for reform in the US. Arthritis care & research. 2011;63(1):31–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]