Abstract

Objectives

The shortage of qualified nurses is one of the critical challenges in the field of healthcare. Among the contributing factors, job burnout has been indicated as a risk factor for the intention to leave. The purpose of this study was to provide a better understanding of the local status and reference data for coping strategies for intensive care unit (ICU)-nurse burnout among Liaoning ICU nurses.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

17 ICUs from 10 tertiary-level hospitals in Liaoning, China.

Participants

431 ICU nurses from 14 ICUs nested in 10 tertiary-level hospitals in Liaoning, China, were invited during October and November 2010.

Primary measures

Burnout was measured using the 22-item Chinese version of Maslach Burnout Inventory-Health Service Survey (MBI-HSS) questionnaires.

Results

14 ICUs responded actively and were included; the response rate was 87.7% among the 486 invited participants from these 17 ICUs. The study population was a young population, with the median age 25 years, IQR 23–28 years and female nurses accounted for the major part (88.5%). 68 nurses (16%) were found to have a high degree of burnout, earning high emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation scores together with a low personal accomplishment score.

Conclusions

The present study indicated a moderate distribution of burnout among ICU nurses in Liaoning, China. An investigation into the burnout levels of this population could bring more attention to ICU caregivers.

Keywords: Burnout, Intensive Care Units, nurses

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to state the actual, overall situation regarding burnout status among intensive care unit (ICU) nurses in Liaoning, China, to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

This multicentre ‘Study to Understand Burnout among Liaoning ICU Nurses’ revealed that as many as 16% of the responding ICU nurses showed a high level of burnout in the emotional exhaustion , depersonalisation and personal accomplishment dimensions.

There may have been important differences in various clinical settings, for example, work climate, characteristics of patients, work load, relationship between doctors and nurses, institutional policy, coping strategies, etc. The results are not generalisable to all Chinese ICU nurses as a whole.

The researcher in each participating ICU was the ICU head nurse, and to some extent, the firsthand acquaintance might affect the information the nurses provided.

Introduction

Around the world, the shortage of qualified nurses is one of the critical challenges in the field of healthcare.1–3 This shortage is a multidimensional phenomenon,4 5 and can be attributed to low job satisfaction, lack of managerial support, poor career opportunities, etc.6 7 Among the contributing factors, job burnout has been indicated as a risk factor for the intention to leave.

Owing to the nature of work, nursing is a stressful occupation; there is direct exposure to various kinds of working environments and conditions which leads to anxiety and depression. In China, the Chinese public is greatly dissatisfied with the high cost and low quality of healthcare.8–11

The study community—the intensive care unit (ICU) nurses—were selected for three main reasons. First, as aforementioned, with the Chinese public's dissatisfaction with healthcare facilities and the high costs of intensive care, there is a tense relationship between doctors and patients; an online survey revealed that 66% of 14 577 doctors said that their hospitals encountered one to three medical disputes per month.10 More efforts have been made to improve the quality of life of patients; however, the care providers deserve equal attention. Second, noise, light and radiation from the monitoring equipments that run all day long directly impact the ICU nurses. Third, critical care medicine was accredited as an independent subspecialty of clinical medicine by the Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China, in January 2009. Critical care courses and educational programmes of various durations taught at hospitals and universities and clinical practices are established to meet the crying need for training during the infancy of critical care research in mainland China.12 The in-service ICU nurses are the main part of the supporting faculty for those under training. A clear picture of the burnout status can provide some background information for the target solutions.

To provide a better understanding of the local status and reference data for coping strategies for ICU-nurse burnout, the present cross-sectional study, ‘Study to Understand Burnout among Liaoning ICU Nurses (the SUBLIN study)’, was conducted to report findings.

Methods

Study units and participants

A cross-sectional survey was conducted during October and November 2010 in Liaoning province, northeastern China. The 486 ICU nurses who work in the 17 intensive care units in 10 tertiary-level hospitals were selected as the target population. The principal investigator and coprincipal investigators contacted the head nurse of each participating ICU via meeting or telephone to share the project objectives and collect feedback on the questionnaire to be used. After the questionnaire was approved by the project core team members and the head nurses of the included ICUs, these head nurses assisted in contacting the nurse staff in first-line clinical positions who agreed to participate and arranging the schedule so that the nurses could be available. The self-administered anonymous questionnaire addressing demographic data and burnout was adopted for the interview. Demographic information included age, gender, education level, marital status, professional title, the entire period of employment as a nurse and an ICU nurse. All the ICU nurses were in a sufficiently good physical and mental condition to provide reliable answers. The procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of China Medical University. To remove participants’ worries that the handwriting on the anonymous questionnaires could be possibly tracked according to their signatures on the consent letter, all participants provided oral informed consent only. After the head nurses informed the eligible participants about the survey, the head nurse in each ICU also explained that participation was purely voluntary and the results based on the collected questionnaire data would be published or presented in an academic symposium on ICU nursing. The head nurse designated at least two people to collect the completed questionnaires and check the integrity. The participating nurses were asked to finish the questionnaire within 5 days and they could complete the questionnaire either at home or in their workplace.

The study population was a dynamic population; some events, such as sick leave, maternity leave or duty travel happened occasionally or frequently. After a negotiation between the principal investigator and the head nurse of each participating ICU, the survey schedule was fixed, and the available nurse participants were defined by the head nurse of each ICU.

Measurement of burnout

Burnout was measured using the self-reporting Chinese version of anonymous Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) questionnaire. It consists of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA). The items in the emotional exhaustion subscale describe the feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one's work; the items in the depersonalisation subscale describe an unfeeling and impersonal response towards recipients of one's care or service and the items in the personal accomplishment subscale describe feelings of competence and successful achievement in one's work with people.13 The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey was translated into Chinese by Samantha Mei-Che Peng from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, its Cronbach's α=0.73 for the whole questionnaire, and 0.86, 0.76 and 0.76 for the three subscales, respectively.14 The scale consists of a total of 22 items, among which the EE dimension is measured by nine items, the DP dimension is measured by five items and the measurement of PE dimension is based on eight items. Each of the items is scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 6. The scores are defined according to how often the statement is experienced, from ‘never’ (0) to ‘every day’ (6). Higher scores on the EE and DP dimensions and lower scores on the PA dimension indicate higher level of burnout. It has been indicated that cut-off points should be nation-specific and clinically derived to respond to cultural values, traditional gender roles and others.15 Cut-off criteria for the MBI-HSS-C in the present study were discussed and determined by the project core team members, EE: low, less than 19; moderate, 19–26; high, more than 26; DP: low, less than 6; moderate, 6–9; high, more than 9; and PA: low, more than 39; moderate, 34–39; high, less than 34.16 Given the fact that the definition of burnout is still controversial, in the present study individuals with high EE and DP scores together with a low PA score were identified as having a high degree of burnout,13 and the distribution data in each subscale were also provided.

Statistical analysis

In China, most of the nurses are women; male nurses, as the minority group, may be at different levels of job burnout when compared with their counterpart female nurses. Thus, a subgroup analysis was conducted to test the differences between male and female nurses. There is an increasing emphasis on higher entrance requirements for ICU nurses, and the amount of nurses’ salary is closely related to their job rank. The job rank of nurses highly relies on their education level, length of service and quantity and quality of scientific output, for example, the number of first-authored publications. Thus education level, job rank, years of employment as a registered nurse and years of employment as an ICU nurse were considered for the subgroup analysis. Age group was classified as <30, 30–40 and >40 years. Years of experience as a registered nurse was grouped as <5, 5–10, 11–19 and more than 20 years. Around 30% of the study population held a junior college diploma and 45% of the study population graduated from a secondary nursing school when first employed as a nurse; part of the nurses attended part-time courses to gain a higher degree. Detailed questions on education level could disclose too much personal information, so only the highest level of education was collected in the present survey to confirm that the survey was anonymous. Marital status may also have an impact on the level of burnout, therefore stratified analysis on marital status was conducted. Differences between MBI scores for demographics and years of experience as a registered nurse or an ICU nurse were tested by the Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). For ordinal data, Mann-Whitney U test was adopted for comparison between two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparison between more than two groups. The proportion of nurses having a high degree of burnout in each subgroup was tested by χ2 test. The Student t test, ANOVA, Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were performed using SPSS software (SPSS V.12.0 for windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The χ2 test was performed with the software Epi Info 3.4.3 (V.3.4.3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA). All p values were two sided with a p value less than 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

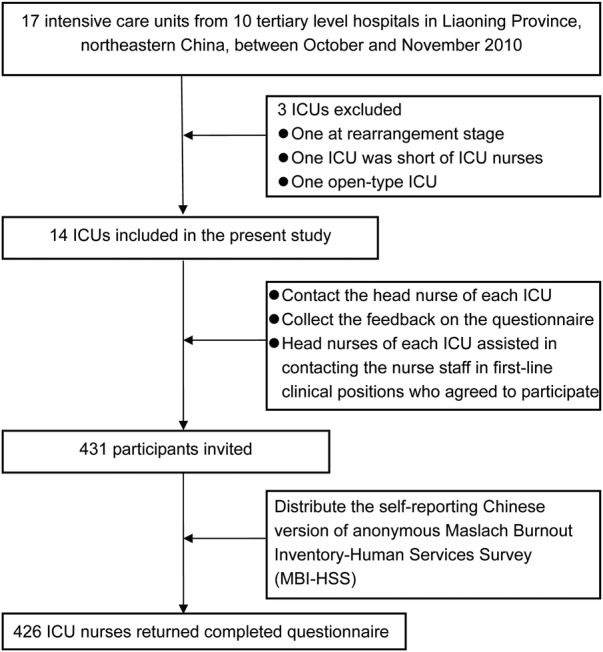

Among the 17 ICUs invited, 14 ICUs from 10 tertiary-level hospitals responded actively and were included in the present study (figure 1). Of the three uninvolved ICUs, one ICU (25 employed nurses) was in the rearrangement stage due to decoration during the study period, one (14 employed nurses) was in the initial stages of being short of ICU nurses and one (16 employed nurses) was an open-type ICU with a management mode distinct from the other ICUs. All the included ICUs were closed-type ICUs with 24 h-a-day presence of junior or intermediate intensivists, and all the nurses’ working shift was 12 h. The characteristics of the 14 included ICUs are shown in table 1. Of the 10 hospitals, half were university and university-affiliated hospitals, three hospitals had more than 2000 beds and the biggest one had 4300 beds. The number of admissions in each included ICU varied from 120 to 890 patients per year.

Figure 1.

Framework of study to understand burnout among Liaoning intensive care unit nurses, the SUBLIN study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 14 included intensive care units in Liaoning province, China, the SUBLIN study

| Characteristics | Number (% or interquartile) |

|---|---|

| Type of hospital | |

| University and university affiliated | 5 (50%) |

| Public | 5 (50%) |

| Number of hospital beds (in 2009) | |

| ≥1000 | 5 (50%) |

| <1000 | 5 (50%) |

| ICU treatment provision by patient category | |

| Medical | 10 (71.4%) |

| Surgical | 4 (28.6%) |

| Number of ICU beds | Median: 12 |

| Interval: 6–28 | |

| Interquartile interval: 9–15 | |

| Number of ICU admissions per year | Median: 300 |

| Interval: 120–890 | |

| Interquartile interval: 165–600 | |

| ICU mortality in 2009 (%) | Median: 14.3 |

| Interval: 4.5–21.0 | |

| Interquartile interval: 9.2–16.7 | |

| Average ICU length of stay (days) | Median: 6.3 |

| Interval: 3–30 | |

| Interquartile interval: 4.5–12.3 | |

| Number of ICU nurses | Median: 26 |

| Interval: 10–76 | |

| Interquartile interval: 19–35 | |

| Patient-to-nurse ratio | Median: 2.2:1 |

| Interval: 2.9:1 to 1.3:1 | |

| Interquartile interval: 2.5:1 to 1.9:1 | |

Of the 431 enrolled participants, 426 (98.8%) responded. Five nurses refused to return the questionnaire. The study population was a young population, with the median age 25 years, IQR 23–28 years and female nurses accounted for the major part (88.5%). Sixty-eight nurses (16%) were found to have a high degree of burnout, earning high EE and DP scores together with a low PA score. The proportion difference with statistical significance was only found in the group defined according to the years of experience as a registered nurse. About one-quarter of those nurses who had been working as a registered nurse for 5–10 years had a high degree of burnout (p=0.02) (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (DP) and personal accomplishment (PA) related to sociodemographic characteristics in 426 ICU nurses in Liaoning province, China

| Variables | Number (%) | Number of nurses having a high degree of burnout | EE |

DP |

PA |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Low | Moderate | High | Mean±SD | Low | Moderate | High | Mean±SD | Low | Moderate | High | |||

| 68 | 24.55 ± 12.36 | 149 | 93 | 184 | 7.05 ± 6.50 | 214 | 101 | 111 | 35.08±9.36 | 154 | 95 | 177 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 377 (88.5) | 59 | 24.49 ± 12.58 | 136 | 80 | 161 | 6.97 ± 6.55 | 194 | 86 | 97 | 35.14±9.62 | 143 | 79 | 155 |

| Male | 49 (11.5) | 9 | 25.06 ± 4.53 | 13 | 13 | 23 | 7.65 ± 6.18 | 20 | 15 | 14 | 34.69±7.12 | 11 | 16 | 22 |

| p Value | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.16 | |||||||

| Age (years, median, 25 years; interval,19–52 years; interquartile interval, 23–28 years) | ||||||||||||||

| <30 | 357 (83.8) | 56 | 24.61 ± 12.29 | 123 | 81 | 153 | 7.18 ± 6.45 | 174 | 86 | 97 | 34.91±9.22 | 123 | 84 | 150 |

| 30–40 | 62 (14.6) | 11 | 24.29 ± 12.84 | 24 | 10 | 28 | 6.50 ± 6.76 | 35 | 14 | 13 | 35.79±10.36 | 28 | 9 | 25 |

| >40 | 7 (1.6) | 1 | 24.14 ± 13.50 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5.14 ± 5.90 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 37.71±7.68 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| p Value | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.51 | |||||||

| Highest level of nurse education | ||||||||||||||

| Secondary nursing school | 57 (13.4) | 7 | 24.98 ± 12.98 | 19 | 13 | 25 | 6.49 ± 5.90 | 29 | 15 | 13 | 34.00±10.02 | 17 | 12 | 28 |

| Junior college | 219 (51.4) | 40 | 25.04 ± 12.05 | 73 | 47 | 99 | 7.81 ± 6.90 | 101 | 54 | 64 | 34.68±8.97 | 71 | 56 | 92 |

| Bachelor and master | 150 (35.2) | 21 | 23.68 ± 12.61 | 57 | 33 | 60 | 6.15 ± 6.00 | 84 | 32 | 34 | 36.08±9.64 | 66 | 27 | 57 |

| p Value | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Job rank | ||||||||||||||

| Nurse or nurse student | 288 (67.6) | 40 | 24.29 ± 11.97 | 100 | 66 | 122 | 7.01 ± 6.33 | 143 | 73 | 72 | 35.20±8.83 | 104 | 67 | 117 |

| Nurse practitioner | 95 (22.3) | 22 | 25.51 ± 12.48 | 31 | 23 | 41 | 7.51 ± 7.11 | 47 | 18 | 30 | 34.18±10.04 | 28 | 23 | 44 |

| Nurse in-charge and higher | 43 (10.1) | 6 | 24.19 ± 14.72 | 18 | 4 | 21 | 6.30 ± 6.32 | 24 | 10 | 9 | 36.30±11.23 | 22 | 5 | 16 |

| p Value | 0.09 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||

| Unmarried | 277 (65.0) | 38 | 24.35 ± 12.48 | 99 | 60 | 118 | 6.96 ± 6.46 | 140 | 68 | 69 | 35.12±9.20 | 99 | 67 | 111 |

| Married | 149 (35.0) | 30 | 24.93 ± 12.17 | 50 | 33 | 66 | 7.21 ± 6.59 | 74 | 33 | 42 | 35.02±9.70 | 55 | 28 | 66 |

| p Value | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.71 | |||||||

| Years of experience as a registered nurse (median, 3 years; interval, 0–32 years; interquartile interval, 3–7 years) | ||||||||||||||

| <5 | 268 (62.9) | 33 | 23.54 ± 12.10 | 102 | 59 | 107 | 6.90 ± 6.40 | 137 | 66 | 65 | 35.43±9.21 | 99 | 61 | 108 |

| 5–10 | 107 (25.1) | 27 | 27.38 ± 12.33 | 29 | 24 | 54 | 7.99 ± 6.99 | 47 | 23 | 37 | 33.58±8.95 | 30 | 27 | 50 |

| 11–19 | 39 (9.2) | 6 | 23.87 ± 13.52 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 5.62 ± 5.64 | 23 | 9 | 7 | 36.15±11.22 | 19 | 5 | 15 |

| 20 or more | 12 (2.8) | 2 | 24.00 ± 12.15 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6.50 ± 6.36 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 37.33±9.37 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| p Value | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.22 | |||||||

| Years of experience as an ICU nurse (median, 2 years; interval, 0–20 years; interquartile interval, 1–4 years) | ||||||||||||||

| <5 | 332 (77.9%) | 46 | 23.89±12.07 | 123 | 73 | 136 | 6.84±6.35 | 169 | 82 | 81 | 35.32±9.19 | 121 | 77 | 134 |

| 5–10 | 82 (19.2%) | 20 | 27.38±13.44 | 22 | 18 | 42 | 7.83±7.18 | 40 | 14 | 28 | 33.65±9.92 | 26 | 17 | 39 |

| 11–19 | 10 (2.3%) | 2 | 24.00±11.08 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 7.70±6.15 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 37.20±10.22 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| 20 or more | 2 (0.5%) | 0 | 21.50±12.02 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5.50±3.54 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 44.00±4.24 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| p Value | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.29 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.23 | |||||||

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

When evaluated in each of the EE, DP and PA subscales, 184, 111 and 177 nurses stayed at the high level of burnout, respectively. Thus the most pronounced symptoms of burnout were emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. Among all the studied variables, statistical significance was found for DP scores among nurses who had a different education level; nurses who held a junior college diploma were with a higher DP score when compared with the other two counterparts (p=0.04) (table 2).

Discussion

This multicentre study revealed that as many as 16% of the ICU nursing teams showed a high level of burnout in all three dimensions. For each subscale, the highest proportion of high-degree burnout (43.2%) was found in the emotional exhaustion subscale, followed by 41.2% in the personal accomplishment subscale and 26.1% in the depersonalisation subscale. Given the fact that the well-being of ICU nurses is of critical importance to the quality of care of critically ill patients who are likely to benefit from ICU care, this kind of investigation into the burnout levels of this population could bring more attention to ICU caregivers.

In Liaoning, China, there are still no complete epidemiological data to state the actual, overall situation regarding burnout status among ICU nurses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first burnout study on Liaoning ICU nurses. Most of the respondents indicated that the investigation from nurses’ perspective might contribute to mutual understanding between nurse leaders, ICU managers and nurses, and their greater self-awareness of burnout. This study strengthened the power of the Critical Care Special Committee nested in Nursing Association of China, Liaoning branch, and added an appeal to the nurse students to work in ICU. When focusing on the prevalence and prevention of occupational burnout in order to develop effective interventions, a few characteristics should be taken into account. There is a linear relationship between emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation; both these subscales can discriminate between burned out and non-burned out employees.17 On the other hand, low levels of personal accomplishment and high degree of depersonalisation in the burnout scores may actually be protective against stress.18 Moreover, high levels of emotional exhaustion cause stress and stress in turn causes high levels of emotional exhaustion. In addition, depersonalisation may reduce stress, whereas high degrees of personal accomplishment may increase stress levels.19

The present study has its limitations. First, of the 17 invited ICUs, 3 ICUs were excluded as 1 ICU was in the rearrangement stage due to decoration during the study period, 1 was in the initial stages of being short of ICU nurses so that its patient-to-nurse ratio was distinct from others and 1 was an open-type ICU that had a management mode distinct from the other 14 included ICUs. Although the rate of response to the questionnaire was excellent, five nurses refused to return the questionnaire after the introduction of study objectives. This refusal might have been related to the fact that they were already exhausted at that time due to various reasons, such as heavy work load. Second, the researcher in each participating ICU was the ICU head nurse, and to some extent, the firsthand acquaintance might affect the information the nurses provided. We tried to minimise this kind of worry; the anonymous questionnaire was a structured one where the participants only needed to put a tick opposite each choice; the pen they used was also provided by the stationary office of each hospital. Thus, it was difficult to trace participant information on the basis of these tick marks. Third, the number of nurses in each participating hospital was more than 1000; the demographic data of total registered nurses in each hospital were available for three hospitals, thus data for the ICU nurses from these three nested ICUs were compared with the total registered nurses of the other hospitals, and no statistical differences were found. In addition, there may have been important differences in various clinical settings, for example, work climate, characteristics of patients, work load, relationship between doctors and nurses, institutional policy, coping strategies, etc. The results are not generalisable to all Chinese ICU nurses as a whole.

This proportion of burnout (16% in all three dimensions, and 26.1–43.2% in each single subscale) among Liaoning ICU nurses who experienced a high degree of burnout is in the range of several recently published studies that reported the distribution of high-level burnout among ICU nurses to be around one-third of the total ICU nurses.20–23 In 2005, a Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey-based investigation was conducted in a convenience sample of staff nurses in Henan province in China.24 In this study the participants were all women, mean age was 29 years with a range from 18 to 60 years and 66% had experience in nursing for 5 years or more. They focused on nurses from provincial hospitals, and supported the view that nurses commonly experience burnout. The authors reported that scores for burnout of surgical and medical nurses were statistically significantly higher than those of other nurses. Lower educational status was also associated with higher levels of burnout in young nurses. However, in the present study, the highest proportion of nurses experiencing a high degree of burnout was found for nurses with 5–10 years of employment as a registered nurse. Around 11.5% of the participants in our study were men, and 63% of the included ICU nurses had less than 5 years of employment as a registered nurse. The differences between that study and our study revealed that burnout was associated with demographic characteristics, such as age, educational level, the kind of clinical setting and years of employment as a nurse or an ICU nurse; caution should be exercised when comparing the results originating from different studies.24

This result might help the ICU head nurse to take some actions to explore the feelings, concerns and difficulties of ICU nurses and explore possible solutions and interventions correspondingly.25 26 High-risk factors27 and possible protective factors28 29 that are associated with burnout levels in Liaoning ICU nurses, such as work environment, job satisfaction, social support and coping strategies will be explored in the next stage of the SUBLIN study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the efforts of 14 collaborative ICUs from 10 hospitals and by the enthusiastic support and active participation of the nurses.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Study Team (SUBLIN Study), Chun-Mei Gu, Li-Huan Hu, Hong-Fei Li, Li-Hong Liu, Long-Feng Sun, Xuan Wang, Xiao-Jiang Yu, Jun-Li Zhang, Li-Hong Zhang, Shen-Ping Zhang, Wen-Jing Zhao, Li-Yuan Zheng.

Contributors: X-CZ conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination. XZ and PG were involved in drafting the manuscript. DSH participated in its design, analysis and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province, China, grant number 2013021014. This work was also a part of the programme for Elaborate Course of Epidemiology and Key Disciplines Construction supported by China Medical University, grant number CMU Internal Circular-J-(2010)-16-31 and Internal Circular-F-(2011)-5).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee of China Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Chun-Mei Gu, Li-Huan Hu, Hong-Fei Li, Li-Hong Liu, Long-Feng Sun, Xuan Wang, Xiao-Jiang Yu, Jun-Li Zhang, Li-Hong Zhang, Shen-Ping Zhang, Wen-Jing Zhao, and Li-Yuan Zhen

References

- 1.Nardi DA, Gyurko CC. The global nursing faculty shortage: status and solutions for change. J Nurs Scholarsh 2013;45:317–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinert J, Bigelow A, Kautz DD. Overcoming nursing faculty shortages and bridging the gap between education and practice. J Nurses Staff Dev 2012;28:216–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed SM, Hossain MA, Rajachowdhury AM, et al. The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable distribution. Hum Resour Health 2011;9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsi Z, Dehghan-Nayeri N, Negarandeh R, et al. Nursing profession in Iran: an overview of opportunities and challenges. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2010;7:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duvall JJ, Andrews DR. Using a structured review of the literature to identify key factors associated with the current nursing shortage. J Prof Nurs 2010;26:309–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynn SD. Addressing the nursing workforce shortage: veterans as mental health nurses. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2013; 51:3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan ZC, Tam WS, Lung MK, et al. A systematic literature review of nurse shortage and the intention to leave. J Nurs Manag 2013;21:605–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiao WC. When incentives and professionalism collide. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:949–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J, Lu M, Quan H. From a national, centrally planned health system to a system based on the market: lessons from China. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:937–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu D, Li T. Facing up to the threat in China. Lancet 2010;376: 1823–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagstaff A, Yip W, Lindelow M, et al. China's health system and its reform: a review of recent studies. Health Econ 2009;18:S7–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du B, Xi X, Chen D, et al. Clinical review: critical care medicine in mainland China. Crit Care 2010;14:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav 1981;2:99–113 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye ZH, Luo H, Jiang HL. Diagnostic standard and norms of Maslach Burnout Inventory for nurses in Hangzhou. Chinese J Nurs 2008;43:207–9 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaufeli WB, Van Dierendonck D. A cautionary note about the cross-national and clinical validity of cut-off points for the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Psychol Rep 1995;76:1083–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Dai Y, Ning Y, et al. Study of the status and correlative factors of job burnout among nurses in Xinjiang. J Nurs Adm 2011;11:7–9 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, et al. On the clinical validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the burnout measure. Psychol Health 2001;16:565–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onder C, Basim N. Examination of developmental models of occupational burnout using burnout profiles of nurses. J Adv Nurs 2008;64:514–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet 2002;359:2089–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teixeira C, Ribeiro O, Fonseca AM, et al. Burnout in intensive care units—a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: a descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol 2013;13:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verdon M, Merlani P, Perneger T, et al. Burnout in a surgical ICU team. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu K, You LM, Chen SX, et al. The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: a nurse questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1476–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S, Zhu W, Wang Z, et al. Relationship between burnout and occupational stress among nurses in China. J Adv Nurs 2007;59:233–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao Y, Yao W, Wang W, et al. Investigation of risk factors of psychological acceptance and burnout syndrome among nurses in China. Int J Nurs Pract 2013;19:530–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lei W, Youn Hee K, Dong W. A review of research and strategies for burnout among Chinese nurses. Br J Nurs 2010;19:844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karanikola MN, Papathanassoglou ED, Mpouzika M, et al. Burnout syndrome indices in Greek intensive care nursing personnel. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2012;31:94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quenot JP, Rigaud JP, Prin S, et al. Suffering among carers working in critical care can be reduced by an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices. Intensive Care Med 2012;38: 55–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beanland C. Tackling the workforce shortage. Aust Nurs J 2013;20:47–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.