Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the literature for evidence of smoking and alcohol intake as independent risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD).

Design

Systematic review.

Methods

MEDLINE (1946—May 2012) and EMBASE (1947—May 2012) were searched for studies investigating alcohol or smoking as risk factors for acquiring IPD and which reported results as relative risk. Studies conducted exclusively in clinical risk groups, those assessing risk factors for outcomes other than acquisition of IPD and studies describing risk factors without quantifying a relative risk were excluded.

Results

Seven observational studies were identified and reviewed; owing to the heterogeneity of study design, meta-analysis was not attempted. Five of six studies investigating smoking reported an increased risk of IPD in the range 2.2–4.1. Four of the six studies investigating alcohol intake reported a significant increased risk for IPD ranging from 2.9 to 11.4, while one reported a significant protective effect.

Conclusions

Overall, these observational data suggest that smoking and alcohol misuse may increase the risk of IPD in adults, but the magnitude of this risk remains unclear and should be explored with further research. The findings of this review will contribute to the debate on whether pneumococcal vaccine should be offered to smokers and people who misuse alcohol in addition to other clinically defined risk groups.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases, Microbiology, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review provides some evidence that smoking and alcohol independently increase the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults.

The findings of the review are relevant to policymakers considering which risk groups should be offered pneumococcal vaccination.

This review was limited by the relatively small number of studies and the heterogeneity of study design.

Introduction

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is a serious illness caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. The bacterium is responsible for a spectrum of illnesses ranging from ear infections to severe systemic, invasive disease such as bacteraemia, bacteraemic pneumonia or meningitis, the long-term effects of which can be profound.1

The pneumococcus is a diverse bacterium with more than 90 serotypes and vaccines have been developed to target the most important of the pneumococcal serotypes.2 In the UK, two vaccines are currently in use: a 13-valent polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PCV13) which replaced PCV7 in 2010 in the childhood immunisation programme and a 23-valent plain polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) for people over 65 years and defined risk groups. The UK policy was updated in July 2013 to offer the conjugate vaccine to those who are clinically severely immunocompromised, while other risk groups continue to receive the plain polysaccharide vaccine.3 Policy on whom to immunise against pneumococcal disease varies internationally but, like the UK, many countries offer immunisation to infants, older people and those in clinical risk groups.4

Since the introduction of the first 7-valent conjugate vaccine into the UK childhood immunisation programme in 2006, there has been an overall reduction in the incidence of reported IPD.5 However, it is well established that some clinical conditions infer an increased risk of contracting IPD, and it is becoming apparent that individuals with such conditions remain at increased risk despite the introduction of conjugate vaccines which induce large herd immunity effects for vaccine serotypes.6 7

Current policy from the UK Department of Health defines the following clinical risk groups as being eligible for pneumococcal immunisation: asplenia or dysfunction of the spleen, chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, diabetes, immunosuppression, individuals with cochlear implants and individuals with cerebrospinal fluid leaks.8 In some countries, including the USA and Australia, the ‘lifestyle’ risk factors of smoking and alcohol (categorised as ‘alcoholism’) are additionally included in pneumococcal immunisation policy for the polysaccharide vaccine, alongside clinical risk groups (table 1). Other countries, including the UK, do not include smoking and alcohol use in their pneumococcal immunisation policy.

Table 1.

International comparison of IPD rates and risk factor immunisation policy

| Country | Crude rate of reported IPD per 100 000 (2010) | Smoking/alcoholism as risk factors in immunisation policy? |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 12.932 | Yes (PPV)26 |

| Australia | 7.433 | Yes (PPV)34 |

| France | 7.935 | No |

| UK | 9.135 | No |

IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PPV, plain polysaccharide vaccine.

Although other reviews have discussed risk factors for IPD,9–11 we are not aware of any other systematic reviews which have attempted to quantify the level of risk associated with smoking and alcohol. As international policy on immunisation of individuals in smoking and alcohol risk groups varies, we set out to systematically review the literature for evidence of these two important lifestyle indicators as independent risk factors for IPD. We also assess the implications of our findings on vaccination policy. This systematic review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.12

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We performed searches with MEDLINE (1946—May 2012) and EMBASE (1947—May 2012) using the following search terms:

Subject headings [risk or risk factors] OR keyword [risk*] AND

Subject headings [Streptococcus pneumoniae or pneumococcal infection] OR keywords [Streptococcus pneumoniae or pneumococc* or IPD or invasive pneumococcal disease] AND

Subject headings [smoking or alcohol] OR keywords [smok* OR alcohol*]

In addition to the main database searches, the reference lists of key studies and reviews were searched to identify any other relevant studies. There were no restrictions on study type or date. We included all studies investigating alcohol or smoking as risk factors for acquiring IPD (defined as disease where S. pneumoniae had been isolated from a normally sterile site). We excluded studies which were conducted exclusively in clinical risk groups (eg, patients with HIV) and studies which only looked at risk factors for outcomes other than acquiring IPD, for example, mortality from IPD. Studies which only described risk factors without quantifying a relative risk were also excluded.

Selection of studies was undertaken independently by two reviewers (HCC and JMJ) in three stages: title scanning, abstract review and full text review. If there was disagreement in the studies selected, consensus was reached before proceeding to the next stage.

Quality assessment

The selected studies were independently assessed for quality by two reviewers (HCC and JMJ) using the framework ‘Quality Appraisal of Correlation Studies’,13 which is used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to develop public health guidance. This is a checklist which allows scoring of internal and external validity of each study, with grades of ++, + and − assigned to each question, taking into account the population, selection of participants, exposure and outcome measures and analyses. A summary score for internal/external validity is obtained, where ++/++ is the highest score which indicates that the study has been carried out in a way which minimises bias and confounding and is generalisable to a wider population. A lower score did not always reflect that a study had been poorly conducted, but instead could indicate that it did not contain sufficient information to determine validity.

Data extraction and synthesis

Standard forms were used by both reviewers to extract data. The parameters collated included study size, setting, population, comparator group, whether smoking and/or alcohol were assessed and analysis of confounders (table 2). As IPD can manifest in different ways and the studies varied in which aspects they had investigated, the studies were grouped according to the disease outcome they had assessed. Risk estimates were extracted for each study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the final seven studies included in the review

| Study | Study population | Number of cases | Comparator | Location | IPD outcome | Confounders measured | Risk factors | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flory et al20 | Adults ≥18 years | 609 | Regional survey data sets | USA | Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia | Gender, ethnicity, age, income, education, diabetes, cancer, asthma | Smoking | +/+ |

| Jacups and Cheng21 | Adults (classified as ≥14 years) | 205 | Regional survey data sets | Australia | Community-acquired bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia | Age, gender, ethnicity, diabetes, alcohol, smoking | Smoking, alcohol | ++/+ |

| Kyaw et al16 | Adults ≥18 years | 4335 | National survey data sets | USA | Invasive pneumococcal disease | Ethnicity, age, diabetes, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, HIV/AIDS | Alcohol | ++/++ |

| Lipsky et al22 | Men attending veterans medical centre | 63 | 130 patients from same medical centre | USA | All pneumococcal disease including IPD | Age, smoking | Smoking, alcohol | +/− |

| Nuorti et al17 | Adults 18–64 years | 228 | 301 age-matched controls | USA/Canada | Invasive pneumococcal disease |

Smoking

Age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic indicators, chronic disease, smoking status, alcohol, study area, status of children in household Alcohol Age, study area |

Smoking, alcohol | ++/++ |

| Pastor et al19 | All ages | 432 | National survey data sets | USA | Invasive pneumococcal disease | Only crude rates reported | Smoking, alcohol | −/− |

| Watt et al18 | Adults ≥18 years from Navajo Nation | 118 | 353 age-matched and sex-matched controls | USA | Invasive pneumococcal disease |

Smoking

No adjustment in analysis but age-matched and sex-matched control study Alcohol Age, PPV, chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, BMI, unemployment |

Smoking, alcohol | ++/+ |

BMI, body mass index; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease.

Results

Identification of studies

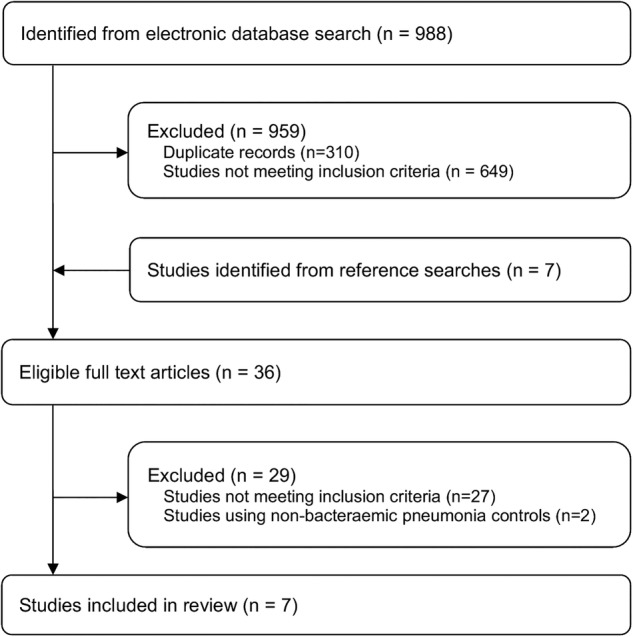

The initial search identified 988 studies and seven additional studies were identified by searching the references of key studies and reviews. After assessment of titles and abstracts, 36 studies were selected for full text review (figure 1). Twenty-seven studies were then excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria and two were excluded14 15 because they assessed risk factors associated with a diagnosis of bacteraemic pneumonia compared with non-bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia and were not designed to assess the risk of smoking or alcohol use on all IPD compared with healthy controls.

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy.

Study characteristics

Of the seven studies remaining for full analysis, six investigated smoking as a risk factor for IPD and six looked at alcohol as a risk factor. The study characteristics are shown in table 2. Four of the studies16–19 used all IPD as the definition for selecting cases, two used bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia20 21 and one used any pneumococcal disease, including IPD.22 The studies presented data on a range of risk factors; however, for the purpose of this review, only data relating to smoking and alcohol were extracted.

Three of the studies17 18 22 were case control studies where controls were selected from either the hospital22 or the community.17 18 In the remaining four studies, risk factors in the cases were compared with risk factor data from regional or national data sets.

Quality of studies

The quality of the included studies varied from the lowest possible score of −/− to the highest possible score of ++/++ (table 2). Where studies did not score highly, there tended to be possible bias from the methods used to measure smoking and alcohol use, a lack of consideration of potential confounders or poor generalisibility. The highest scoring studies may still have had limitations inherent in observational studies, but were considered to be of a higher quality compared to the others in the review.

Smoking and alcohol as risk factors for IPD

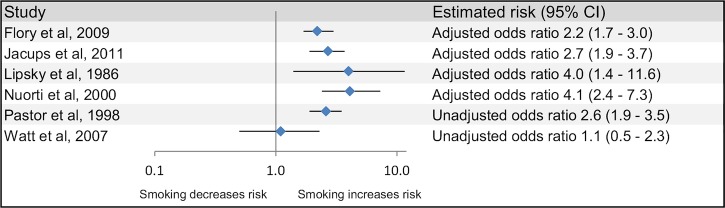

Meta-analysis was not attempted due to heterogeneity; the studies differed considerably in methodological design, risk factor assessment and disease groupings. Although there was variation in how the risk factors and comparators were defined, five of the six studies which analysed smoking reported a significant increase in risk for current smoking (figure 2). For the five studies which reported an increased risk, estimates ranged from an OR of 2.2 (1.7 to 3.0)20 for bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia to 4.1 (2.4 to 7.3) for all IPD17 (table 3). The sixth study reported a non-significant increase in risk in smokers. Of the six studies which considered alcohol as a risk factor for IPD, four reported a significantly increased risk, ranging from an OR of 2.9 (1.5 to 5.4)18 to a rate ratio of 11.4 (5.4 to 21.916; figure 3). Since the disease is rare, the rate ratio was considered comparable with the ORs. In the two remaining studies, one suggested a reduced risk of IPD with moderate alcohol use (OR=0.7 (0.5 to 1.0))17 and the other showed a non-significant decrease in risk for heavy drinking and a non-significant increase for alcohol abuse.22

Figure 2.

Smoking and the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease.

Table 3.

Estimated risks by disease outcome

| Study | Comparison | Estimated risk—smoking (95% CI) | Comparison | Estimated risk—alcohol (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All IPD | ||||

| Kyaw et al16 | – | Not reported | Alcohol abuse* vs no alcohol abuse | 11.4 (5.9 to 21.9)† |

| Nuorti et al17 | Current‡ vs never-smoker with no passive smoking Former smoker‡ vs never-smoker with no passive smoking |

OR=4.1 (2.4 to 7.3) OR=1.1 (0.5 to 2.2) |

Moderate§ vs none | OR=0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) |

| Pastor et al19 | Current vs non-smoker | OR=2.6 (1.9 to 3.5) (unadjusted) | Heavy alcohol use¶ vs not heavy use | OR=4.1 (2.9 to 6.1) (unadjusted) |

| Watt et al18 | Current** vs never-smoker Former** vs never-smoker |

OR=1.1 (0.5 to 2.3) (unadjusted) OR=1.5 (0.8 to 2.8) (unadjusted) |

Alcohol use or alcoholism vs no alcohol use††† | OR=2.9 (1.5 to 5.4) |

| Bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia | ||||

| Flory et al20 | Current vs not current or never | OR=2.2 (1.7 to 3.0) | – | Not reported |

| Jacups and Cheng21 | Smoking vs not smoking | OR=2.7 (1.9 to 3.7) | Excess alcohol†† vs no alcohol excess | OR=4.8 (2.8 to 8.3) |

| All pneumococcal disease | ||||

| Lipsky et al22 | Current‡‡ vs never Former‡‡ vs never |

OR=4.0 (1.4 to 11.6) OR=2.1 (0.8 to 6.0) |

Heavy*** vs moderate Abuse*** vs moderate |

OR=0.7 (0.5 to 3.5) OR=1.3 (0.4 to 4.3) (unadjusted) |

*Alcohol abuse: men who consumed more than 20 drinks/week and women who consumed more than 16 drinks/week.

†Rate ratio.

‡Current smoker: still smoking or quit within the previous year and former smoker: quit more than 1 year previously.

§ Moderate drinking: more than 0 and fewer than 25 alcoholic drinks per week in the previous month. Heavy drinking was also included in this study but excluded from this analysis because of low numbers (n=2).

¶Heavy alcohol use: daily consumption of alcohol or a diagnosis of alcoholism.

**Current smoking: at least 100 cigarettes in the past year and former smoking (at least 100 cigarettes in the past without current smoking.

††Alcohol excess: average daily consumption greater than 60 g alcohol for men and 40 g for women.

‡‡Current smoker: smoked within the previous 6 months and former smoker: quit more than 6 months previously.

***Heavy alcohol use (at least 5 drinks on at least 5 days a week) and alcohol abuse (documented medical or psychosocial problems caused by alcohol).

†††Uses alcohol: self-reported alcohol use or alcoholism (either a diagnosis of alcoholism in medical record or documentation of conditions due to alcohol use).

IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease.

Figure 3.

Alcohol and the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease.

Discussion

This systematic review assessed the evidence for smoking and alcohol as risk factors for developing IPD in adults. We found that there was some limited, but not conclusive, evidence that smoking and alcohol are independent risk factors for IPD. The results for smoking were more consistent than for alcohol. All six studies investigating smoking as a risk factor found an increased risk (although 1 of these was not significant), regardless of the quality of the study. Of the studies reporting a significantly increased risk, OR estimates ranged from 2.2 (1.7 to 3.0) to 4.1 (2.4 to 7.3) for current smoking, indicating at least a doubling of risk for IPD. The results for alcohol were more variable, which may reflect the greater complexity in measuring and categorising alcohol intake compared with smoking. For alcohol, the lowest risk estimate was an OR of 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0), which was suggestive of a protective effect, and the highest estimate was a rate ratio of 11.4 (5.9 to 21.9) indicating a significant increase in risk. However, the studies used different methods of quantifying alcohol intake; the lowest estimate used moderate drinking (0 to 25 alcohol drinks per week) and the higher estimate used alcohol abuse (men who consumed more than 20 drinks/week and women who consumed more than 16 drinks/week).

Strengths and limitations

The studies included in this review were identified through comprehensive and systematic searches of international databases. However, the review itself was limited by the relatively small number of studies found which had reported results for smoking and alcohol as risk factors for IPD. Given the heterogeneity of study design, including different clinical end points, meta-analysis was not appropriate and thus a summary estimate was not obtained.

All the seven studies were observational studies, and as such were inherently vulnerable to bias. A particular source of bias in individual studies was likely to be the way in which smoking and alcohol status were determined. ‘Smoking’ and ‘alcohol’ are broad terms and were interpreted differently in the studies, but the way in which the data were collected also varied, for example, by questionnaire or extracting data from medical records. Self-reporting of lifestyle risk factors or reliance on clinicians’ recording of them will inevitably result in some degree of error. Risk factors are likely to be under-reported in both cases and controls, leading to bias towards the null hypothesis. The differences in how smoking and alcohol use were defined also made it difficult to compare the risks between studies. Publication bias may also be a consideration in this review if there was a tendency to publish only those results where a positive association is shown.

The data in this review were derived from studies which took place at different time points over three decades. Over this period, there have been changes which may have influenced risk factor studies, for example, development of vaccination policy and practice, and changes in circulating pneumococcal serotypes. An additional consideration is that the methodology used in these studies meant that exposure was assessed at, or around, the time that the outcome (IPD diagnosis) occurred, rather than measured over time. The studies did not describe the duration of exposure, apart from in the most general terms, and this is another factor which could account for some variability between studies.

The quality of studies in this review was influenced by the extent to which confounding was taken into account, either at the design or analysis stage. Two of the case control studies17 18 used matching of age and/or gender of cases and controls to reduce confounding by these factors in the design stage. Other studies attempted to eliminate potential confounders using multivariable analysis techniques. There was no consistency in how the risk estimates had been adjusted for confounders, and one study19 reported only unadjusted ORs. Confounding could have a significant impact on the results of these risk factor estimates. For example, a recent study reported a more than fourfold increased risk of IPD among adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)23 and, given the link between smoking and COPD, this could be an important confounder. Despite the limitations associated with observational studies, they remain a useful tool for the investigation of multiple risk factors in relatively rare diseases such as IPD.

Biological mechanisms

Observational studies may provide evidence for an association between an exposure and a disease but cannot establish causality. In the case of IPD, there is some evidence from this review that smoking and alcohol can be independent risk factors for the disease. This epidemiological link is supported to some extent by the existence of possible biological mechanisms through which smoking and alcohol could increase the risk of IPD. There are a number of ways in which smoking may increase the risk of invasive pneumococcal infection: by increasing bacterial carriage; suppressing the immune system; impairing wound healing; disrupting the respiratory epithelium or impairing mucocilliary clearance.24 There is a substantial body of evidence that shows that alcohol has specific effects on particular parts of the immune system (for a review, see Szabo and Mandrekar25) and this could lead to an increased susceptibility to bacterial infections such as IPD in people who drink above safe levels.

Implications for policy

Alcoholism has been an indication for pneumococcal immunisation of adults in the US national recommendations for many years, and smoking has more recently been included.26 These two risk factors are also included in Australia's pneumococcal vaccination programme. The UK vaccination recommendations do not include either of these indications, in line with other European countries. The results of the review provide some evidence that smoking and alcohol are risk factors for IPD. However, this was based on a small number of heterogeneous studies and should be interpreted with caution.

Any decision on changing vaccination recommendations to include people who smoke or misuse alcohol in the risk groups for pneumococcal vaccination needs to take into account not only the epidemiological evidence but also the wider considerations such as: the uncertainty over the effectiveness of vaccination in adults with chronic disease;27 whether priority should be given to improving immunisation rates in currently defined risk groups (eg, the HIV-positive population has an estimated incidence of IPD 40 times higher than the HIV-negative population28) or whether resources should be focused instead on reducing the burden of smoking and alcohol misuse in the population.

In England, 20% of adults report current smoking.29 A potential increase of this magnitude in the demand for pneumococcal immunisation would impose a significant additional burden on primary care services. However, many smokers will already be eligible for pneumococcal vaccination as smoking is a risk factor for chronic health conditions such as COPD and coronary heart disease that are currently included in the criteria. Likewise, alcohol misuse is a risk factor for chronic liver disease, which is also included. It is therefore difficult to estimate the additional immunisation burden such a policy change would create.

Implication for clinical practice

Specifying risk groups for pneumococcal immunisation is just one aspect of the vaccination programme. The process through which the recommendations are implemented and risk groups are targeted presents its own challenges. A successful vaccination programme needs to have appropriately trained health professionals, sufficient vaccine and clinic resources and a range of opportunities for vaccination and willing patients. A study in the UK showed that only 8% of adult patients with IPD with a known risk factor (excluding age) had been vaccinated.30 In the USA, PPV coverage for high-risk adults aged 19–64 in 2009 was 17.5%.31 This demonstrates the challenge in identifying risk groups and the need to opportunistically vaccinate wherever possible. Given these low estimates of vaccination in high-risk groups, it is important that attention is focused on improving immunisation rates alongside consideration of which risk groups to include in the immunisation programme. If the UK did, in the future, expand its recommendations to include smoking and alcohol or other risk factors, consideration would need to be given to how the groups could effectively be targeted and vaccinated. Alcohol use in particular would need clear definitions to enable health professionals to identify appropriate individuals.

Implications for further research

This review has identified that further research would be helpful in understanding lifestyle risk factors for IPD. The published studies quantifying smoking and alcohol as risk factors are few in number and variable in methodology and quality. Additional research with a more detailed exploration of the exposures (eg, dose response) and using consistent classifications of levels of use would further develop understanding in this field and help to inform policy. If smoking and alcohol misuse were to be included in pneumococcal risk groups in countries where they are not currently included, policymakers would need to be confident that the available vaccines would provide adequate protection. The UK Green Book states that PPV23 is ‘relatively inefficient’ in chronic alcoholism, although this is not referenced. Further studies on the efficacy of PCV13 and PPV23 in smokers and people who misuse alcohol are required.

Conclusions

Although limited by the small number of eligible studies and the variation in methodology, this is an important review as it brings together the existing evidence for a significant public health question and highlights the need for further investigations. Policymakers may want to consider offering pneumococcal vaccine to smokers as there appears to be some evidence for an increased risk of IPD in this group. However, the large number of smokers in the UK means that such a decision should also consider the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccines in this group, the cost effectiveness of this approach as well as the opportunity costs. Further evidence on the risk of alcohol use for IPD and the effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccines for those who misuse alcohol is required before considering their inclusion in those indicated for pneumococcal vaccine.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HCC, JMJ and SCC conceived the study; HCC and JMJ developed the search terms and performed the literature search, independently selected studies for review, reviewed the studies, came to a consensus on the studies to include and extracted data. HCC and JMJ wrote the draft manuscript while SCC revised the final manuscript. HCC, JMJ and SCC approved the final version for publication.

Funding : This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SCC currently receives unrestricted research funding from Pfizer Vaccines (previously Wyeth Vaccines) and GlaxoSmithKline. JMJ currently receives research funding from Pfizer Vaccines (previously Wyeth Vaccines). JMJ and SCC have received consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline; SCC and JMJ supervise PhD students who are funded by Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline; the spouses, partners or children of all authors have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and SCC and JMJ have received financial assistance from vaccine manufacturers to attend conferences. All grants and honoraria are paid into accounts within the respective NHS Trusts or Universities, or to independent charities.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Edmond K, Clark A, Korczak VS, et al. Global and regional risk of disabling sequelae from bacterial meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:317–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gladstone RA, Jefferies JM, Faust SN, et al. Continued control of pneumococcal disease in the UK—the impact of vaccination. J Med Microbiol 2011;60:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. JCVI statement on the wider use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in the UK. Department of Health, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2013 global summary. [online]

- 5.Miller E, Andrews NJ, Waight PA, et al. Herd immunity and serotype replacement 4 years after seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in England and Wales: an observational cohort study. Lancet 2011;11:760–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Hoek AJ, Andrews N, Waight PA, et al. The effect of underlying clinical conditions on the risk of developing invasive pneumococcal disease in England. J Infect 2012;65:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhammad RD, Oza-Frank R, Zell E, et al. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among high risk adults since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for children. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:e59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Immunisation against infectious disease (The Green Book) Chapter 25: Pneumococcal—updated 19 April 2013. [on-line]

- 9.Schoenmakers MCJ, Hament JM, Fleer A, et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease. Rev Med Microbiol 2002;13:29–36 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman C, Anderson R. New insights into pneumococcal disease. Respirology 2009;14:167–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch IJP, Zhanel GG. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009;30:189–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition), [online] [PubMed]

- 14.Jover F, Cuadrado J-M, Andreu L, et al. A comparative study of bacteremic and non-bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musher DM, Alexandraki I, Graviss EA, et al. Bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. A prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:210–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyaw MH, Rose CE, Jr, Fry AM, et al. The influence of chronic illnesses on the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults. J Infect Dis 2005;192:377–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. N Engl J Med 2000;342:681–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt JP, O'Brien KL, Benin AL, et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease among Navajo adults. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1080–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor P, Medley F, Murphy TV. Invasive pneumococcal disease in Dallas County, Texas: results from population-based surveillance in 1995. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:590–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flory JH, Joffe M, Fishman NO, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:717–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacups SP, Cheng A. The epidemiology of community acquired bacteremic pneumonia, due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, in the top end of the northern territory, Australia-over 22 years. Vaccine 2011;29:5386–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipsky BA, Boyko EJ, Inui TS, et al. Risk factors for acquiring pneumococcal infections. Arch Intern Med 1986;146:2179–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inghammar M, Engström G, Kahlmeter G, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in patients with an underlying pulmonary disorder. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013;19:1148–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huttunen R, Heikkinen T, Syrjanen J. Smoking and the outcome of infection. J Intern Med 2011;269:258–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szabo G, Mandrekar P. A recent perspective on alcohol, immunity, and host defense. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:220–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease C, Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization P. Updated recommendations for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults using the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:1102–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moberley S, Holden J, Tatham D, et al. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen AL, Harrison LH, Farley MM, et al. Prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among HIV-infected adults in the era of childhood pneumococcal immunization. AIDS 2010;24:2253–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health and Social Care Information Centre, Lifestyles Statistics. Statisitcs on smoking: England, 2012: HSCIC, 2012

- 30.Parsons HK, Metcalf SC, Tomlin K, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease and the potential for prevention by vaccination in the United Kingdom. J Infect 2007;54:435–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009 Adult Vaccination Coverage, NHIS [on-line]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active bacterial core surveillance report, emerging infections program network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2010. Atlanta: CDC, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.NNDSS Annual Report Writing Group. Australia's notifiable disease status, 2010: annual report of the national notifiable diseases surveillance system. Commun Dis Intell 2012;36:1–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. The Australian Immunisation Handbook, 10th Edition 2013

- 35.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Annual epidemiological report 2012. Reporting on 2010 surveillance data and 2011 epidemic intelligence data Stockholm: ECDC, 2013 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.