Abstract

Objectives

To describe the risk factors for treatment delay and the effect of delay on the severity of tuberculosis (TB) in a prospectively followed TB cohort at the Bandim Health Project in Guinea-Bissau.

Background

Treatment delay in patients with TB is associated with increased mortality and transmission of disease. However, it is not well described whether delay influences clinical severity at diagnosis. Previously reported risk factors for treatment delay vary in different geographical and cultural settings. Such information has never been investigated in our setting. Change in delay over time is rarely reported and our prospectively followed TB cohort gives an opportunity to present such data.

Participants

Patients were included at the time of diagnosis at three local TB clinics and the national TB reference hospital. Inclusion criteria were age >15 years and diagnosis of TB by either sputum examination or by the WHO clinical criteria. Patients with extrapulmonary TB were excluded.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was treatment delay. Delay was assessed by patient questionnaires. The secondary outcome was Bandim TBscore as a measure of TB morbidity and all-cause mortality.

Results

A total of 1424 persons were diagnosed with TB in the study area between 2003 and 2010. We included 973 patients with TB in the study. The median treatment delay was 12.1 weeks. Risk factors for delay were low educational level, HIV-1+HIV-2 dual infection and negative sputum smear. TB treatment delay decreased by 10.3% (7.9–12.6%) per year during the study period. Delay was significantly associated with clinical severity at presentation with 20.8% severe TB cases in the low delay quartile compared with 33.9% if delay was over the median of 12.1 weeks.

Conclusions

Long treatment delay was associated with more severe clinical presentation. Treatment delay in TB cases is decreasing in Guinea-Bissau.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A continuous and well-described cohort of patients with tuberculosis (TB) was used and a large number of TB cases were included. Cases were followed with clinical exams after treatment and mortality follow-up.

Division between patient delay and healthcare system delay was not possible since date of first contact to any healthcare provider could not be estimated validly. While this weakens the specificity of our findings it does not influence our results on severity of disease.

There is a risk of recall bias since the data were collected by retrospective questionnaires. Cultural and educational factors may have influenced the estimated treatment delay.

Introduction

It is estimated that one-third of the world's population is latently infected with tuberculosis (TB).1 In 2013 the WHO estimated that there were 8.6 million cases of active TB with 1.3 million deaths annually.2 Of these deaths, over 95% occurred in low-income and middle-income countries.3 Transmission of TB is difficult to control since one index case can infect a large number of secondary cases if left untreated.4–6 Better management of TB should focus on reducing the time delay from symptom onset to initiating treatment.5 7 Treatment delay is influenced by gender, age, sputum TB smear status, distance to nearest healthcare provider, educational level and HIV status.8 9

Previously reported treatment delays from different parts of the world vary considerably. A study from China found a total time delay of 3.6 weeks7; a study from Tanzania found a delay of 26 weeks.10 The average delay in low-income countries has been reported to be 9.7 weeks.8

Factors affecting treatment delay are of key importance in TB management as delay may increase mortality.11 12 However, there is limited data on the effect of delay on clinical severity at presentation. The aim of this study was to describe risk factors for treatment delay, to assess the possible effects of treatment delay on clinical severity at diagnosis and to monitor changes in delay over time in a prospective TB programme.

Materials and methods

Study design

Our study was a longitudinal prospective cohort including all patients diagnosed with TB within the Bandim Health Project (BHP) study area. Inclusion criteria were age >15 years and diagnosed with TB by either sputum examination (smear microscopy; no culture was available) or by the WHO clinical criteria.13

Study location and population

The study was carried out in Bissau, the capital of Guinea-Bissau, at the BHP. The BHP is a health and demographic surveillance site (HDSS), which has followed an urban population in Bissau since 1978. The study area consists of six suburban areas with a total population of 102 000, which is followed by regular demographic surveys. All individuals in the area are registered with their ID number, age, sex, ethnic group and socioeconomic data. Censuses are performed at regular intervals and information on pregnancies, births, mortality and migration is collected on a daily basis. Since 1996 a surveillance system has detected all patients diagnosed with and treated for TB in the study area, and long-term follow-up has been performed. In 1997 an estimated TB incidence rate of the study area was one of the highest reported TB incidences in the world (470/100 000 person years)14; a recent study estimated a current incidence of 288/100 000 person years.15

Health services and inclusion

Field assistants identified patients at the TB treatment facilities during daily visits. Patients were identified at treatment start and invited for consultation and enrolment. Not all patients showed up for enrolment; those not enrolled in the epidemiological study did not complete the questionnaire nor underwent the clinical examination, hence no delay or severity information was available for these patients. Patients were interviewed using a structured questionnaire including data on first signs and symptoms of TB and demographic characteristics.16 The inclusion period was from 1 November 2003 to 4 June 2010; data were analysed in June 2010 and the questionnaire was adapted for future studies.

During treatment patients were followed through regular clinical evaluations, the last being in the sixth and last month of treatment. Mortality follow-up was conducted through house visits 12 and 24 months after termination of treatment.

Definitions

Treatment delay was defined as the time from onset of TB symptoms to the initiation of specific anti-TB treatment. At inclusion in the cohort, patients were asked when the first symptoms of the disease occurred and what the initial symptoms were. From the responses, it was often difficult to make a clear assessment of the exact time of first contact to a healthcare facility and a distinction between patient-related and healthcare system-related delay was not possible.

Many people from rural areas move temporarily to the capital city to work or to access the health services. These patients without a permanent address in the study area were classified as ‘non-residents’.

The study was conducted in an urban environment and physical access to healthcare facilities was therefore not considered a major factor in delay.

Laboratory tests

An HIV test was performed at inclusion using Enzygnost anti-HIV-1 +anti-HIV- 2 Plus (Behring Diagnostics Gmbh, Marburg, Germany) and confirmed with Capillus HIV-1/HIV-2 (Cambridge Diagnostics, Galway, Ireland) or Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la Coquette, France). From January 2008, Determine HIV-1/HIV-2 (Alere Inc, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used and positive results were confirmed with SD Bioline HIV-1/HIV-2 3.0 (Standard Diagnostics Inc, Korea). Tests for HIV were repeated at 6 months and for 13 cases with an inconclusive initial HIV test the result of the next test after 6 months was used. Direct microscopy of sputum samples was performed using Ziehl-Neelsen staining. Laboratory facilities for sputum cultures were destroyed during a civil war in Guinea-Bissau and were therefore not performed in the present study.17

Bandim TBscore

Clinical severity was assessed by the Bandim TBscore. The TBscore is a newly developed tool assessing change in clinical status of patients with TB18 expressed as a numeric index based on cough, haemoptysis, dyspnoea, chest pain and night sweating18 and the following findings: anaemic conjunctivae, tachycardia, positive lung auscultation, increased temperature, body mass index (BMI) and middle upper arm circumference (MUAC). The TBscore can be divided into three severity classes and a TBscore ≥8 correlates with mortality and lower TBscores with favourable outcomes, cure and completed treatment as described elsewhere.18 19 In these previous validations and also in other settings20 severe TB has been defined as TBscore ≥8, which has a strong prognostic capacity for mortality.

Statistical analysis

Data were double entered and analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software V.11 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). To account for outliers in the reported treatment delay, medians were presented in tables and figures and logarithmic transformation was performed. The data were reanalysed excluding these outliers but no significant change in estimates was observed. A multiple linear regression model was used to adjust for multiple risk factors in the treatment delay analysis. Cox regression was used in the mortality analysis (figure 1) and in the depiction of time to TB treatment for symptomatic TB cases (figure 2). No significant deviations from the proportional hazard assumption were found. Factors affecting the association between treatment delay and mortality with ≥10% were corrected for and the same cut-off was used in the supplementary logistic regression model on treatment delay and severity. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant. Correction for calendar time was performed in the adjusted risk factor analysis (table 2).

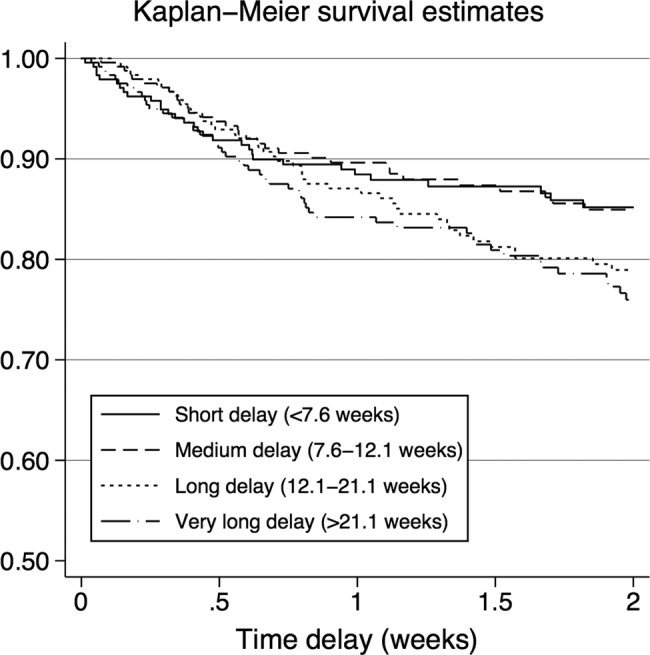

Figure 1.

The graph describes the relation between treatment delay and mortality. Strata were created from 25th centiles of median treatment delay.

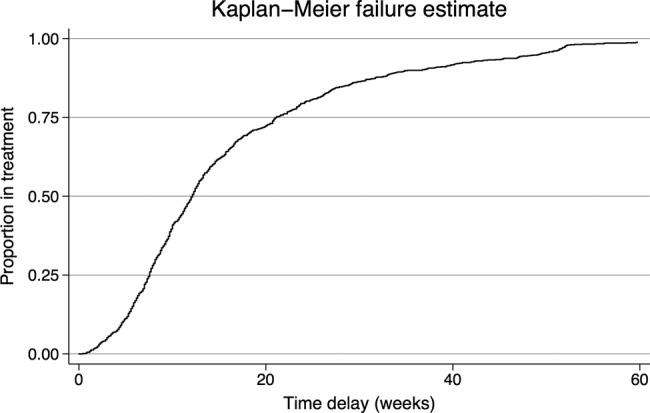

Figure 2.

Treatment delay was defined as the time from self-reported onset of TB symptoms to the initiation of specific antituberculosis treatment. All patients were in treatment by the end of the analysis period because only those patients who ultimately began treatment were included in this analysis.

Table 2.

Risk factors for total treatment delay (n=973*)

| N | Median (weeks) | RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 602 | 11.4 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 371 | 12.7 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.28) | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.18) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–24 | 186 | 10.9 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–34 | 351 | 11.4 | 1.05 (0.91 to 1.22) | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.15) |

| 35–44 | 209 | 12.0 | 1.10 (0.94 to 1.29) | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.14) |

| 45+ | 227 | 14.9 | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.54) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) |

| Civil status | ||||

| Single | 439 | 10.7 | 1 | 1 |

| Married | 383 | 12.4 | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.37) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) |

| Divorced/widow(er) | 151 | 14.6 | 1.42 (1.23 to 1.65) | 1.15 (0.86 to 1.37) |

| Education | ||||

| 9+ years | 199 | 9.7 | 1 | 1 |

| 7–9 years | 208 | 10.0 | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.31) | 1.10 (0.94 to 1.28) |

| 1–6 years | 264 | 12.6 | 1.36 (1.17 to 1.57) | 1.23 (1.05 to 1.44) |

| No education | 290 | 15.1 | 1.55 (1.34 to 1.79) | 1.24 (1.03 to 1.49) |

| Data missing | 12 | 17.2 | 1.50 (0.94 to 2.38) | – |

| Residence | ||||

| Resident | 721 | 11.3 | 1 | 1 |

| Guest | 252 | 15.1 | 1.32 (1.18 to 1.48) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.24) |

| HIV status | ||||

| HIV negative | 665 | 11.9 | 1 | 1 |

| HIV-1 | 187 | 12.3 | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.17) |

| HIV-2 | 79 | 12.0 | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.17) | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.04) |

| HIV-1+HIV-2 | 39 | 16.0 | 1.40 (1.08 to 1.82) | 1.31 (1.01 to 1.70) |

| Data missing | 3 | 21.0 | 2.05 (0.82 to 5.14) | – |

| Sputum smear status | ||||

| Smear positive | 630 | 11.6 | 1 | 1 |

| Smear negative/no expectoration | 343 | 12.7 | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.32) | 1.13 (1.02 to 1.25) |

| BMI | ||||

| Normal (BMI >18.5) | 435 | 11.1 | 1 | |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 524 | 12.6 | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.22) | – |

| Data missing | 14 | 12.3 | 1.01 (0.66 to 1.56) | – |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Mancanha/Manjaco | 251 | 11.9 | 1 | 1 |

| Balanta | 143 | 13.4 | 1.25 (1.06 to 1.48) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.32) |

| Fula | 240 | 11.8 | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.16) | 1.12 (0.82 to 1.52) |

| Pepel | 232 | 12.7 | 1.12 (0.97 to 1.30) | 1.13 (0.98 to 1.31) |

| Other | 100 | 11.7 | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.32) | 1.10 (0.90 to 1.33) |

| Data missing | 7 | 13.0 | 1.26 (0.68 to 2.31) | – |

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 346 | 11.0 | 1 | 1 |

| Traditional religion | 265 | 14.7 | 1.32 (1.16 to 1.50) | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.25) |

| Protestant | 84 | 11.1 | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.17) | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.09) |

| Muslim | 260 | 11.4 | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.16) | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.18) |

| Other | 17 | 12.4 | 1.17 (0.79 to 1.73) | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) |

| Data missing | 1 | 11.9 | 1.05 (0.22 to 5.12) | – |

*In the multiple regression model twenty-two patients were not included due to missing information on one or more risk factors (see figure 1).

†The adjusted analysis was corrected for calendar time.

Ethics

The patients were informed in written Portuguese and verbally in the common language Creole and they gave consent by signature or fingerprint. The study was permitted by the Health Ministry of Guinea-Bissau and approved by the National Science and Ethics Committee in Guinea-Bissau as well as the Central Ethics Committee of Denmark.

Results

Patient characteristics

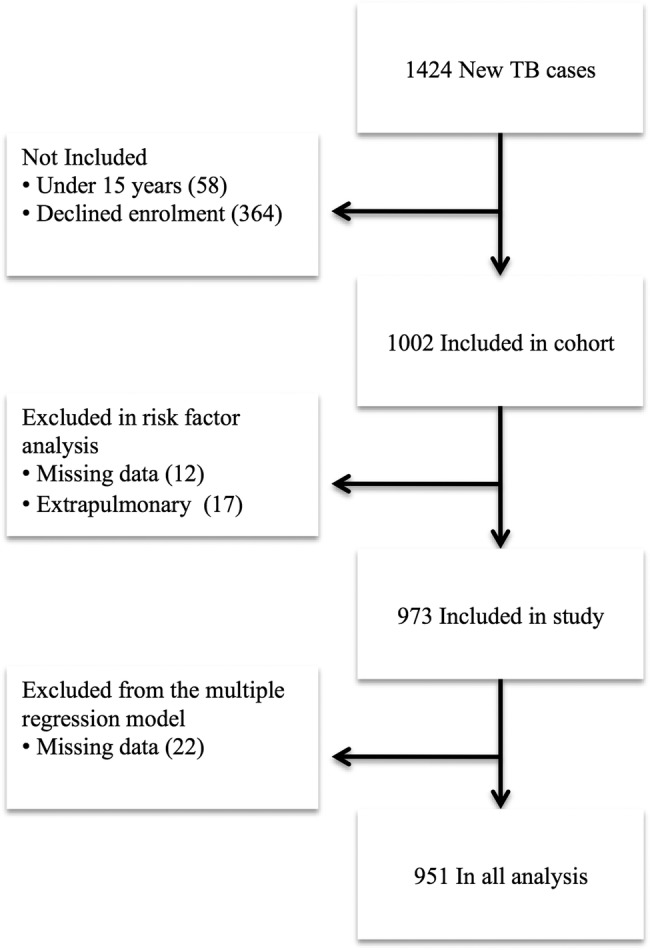

A total of 1424 persons were diagnosed with TB in the study area. Of these, 58 were under the age of 15 years and 364 were not enrolled. Thus, 1002 were enrolled in the cohort (figure 3). We excluded 17 patients due to extrapulmonary TB and 12 due to missing data at the time of symptom onset. Hence, 973 patients were included in the final analysis (62% men and 38% women). The mean age was 36 years (median 33; range 15–90) for men and 35.4 years (median 31; range 15–75) for women.

Figure 3.

Flowchart demonstrating included individuals.

Information about non-included patients was generally limited to gender and age. Residential status was known for 153 of these patients. Non-included cases were older than included patients with a mean age of 38 years (median 35; range 15–98) compared with 35.7 years (median 32; range 15–90) (p<0.01). Non-included patients were more often non-residents; 34% (52/153) were from outside the study area, compared with 26% (252/973) in the included group (p=0.03), but there was no significant difference in gender (p=0.87).

The median treatment delay was 12.1 weeks; 10% of patients were still not on anti-TB treatment after 37 weeks as described in figure 2, which displays the proportion of the diagnosed and treated patients among the enrolled patients with TB in this study.

Symptoms of TB

The first self-reported symptoms of TB are described in table 1, which comprises all symptoms mentioned by patients as initial symptoms of their current illness; no attempt was made to differentiate which symptom was the first. There were no data available on the type of first symptoms for 43 patients. The most frequent initial symptoms were cough, fever and chest pain. In total, 89.8% (874/973) reported cough at the time of treatment initiation and the median time with cough before diagnosis was 12.9 weeks (interquartile range (IQR) 8.6–21.4).

Table 1.

First self-reported symptoms of TB (n=930*)

| TB smear positive (n=600) | TB smear negative/no expectoration (n=330)† | |

|---|---|---|

| Cough | 88% (530/600) | 87% (286/330) |

| Fever | 80% (482/600) | 85% (279/330) |

| Chest pain | 80% (477/600) | 84% (276/330) |

| Weight loss | 55% (330/600) | 63% (208/330) |

| Night sweating | 16% (95/600) | 17% (55/330) |

| Breathlessness | 14% (85/600) | 16% (52/330) |

| Haemoptysis | 6% (37/600) | 8% (27/330) |

| Other symptoms | 1% (6/600) | 1% (2/330) |

*Forty-three cases did not provide information on the nature of first TB symptoms.

†There were no significant differences between the two groups (p>0.05).

Risk factors for treatment delay

The risk factor analysis is shown in table 2. In the multiple regression analysis 22 cases were excluded due to missing information in one or more variables. No education, negative smear and HIV-dual infection remained significantly associated with treatment delay.

Of the 973 patients, 290 had never attended school and had a longer median time to treatment (15.1 weeks) than patients with schooling (p=0.02). There was no significant difference in treatment delay between cases with an intermediate educational level (7–9 years) and a high educational level (>9 years) (p=0.135).

Patients with no expectoration or a negative TB smear had a longer treatment delay than patients with a positive TB smear (12.7 vs 11.6 weeks) (p=0.03).

Stratifying the risk factor analysis on TB smear status did not change estimates significantly although ethnicity, religion and marital status were not found to be significant risk factors for sputum negative cases.

Bandim TBscore and mortality

Bandim TBscore was available for all 973 patients (table 3). We defined the lowest quartile as short treatment delay, followed by moderate, long and very long delay.

Table 3.

Treatment delay and clinical severity

| Centile (%) | Delay (weeks) | TBscore | Percentage of severe TB cases* | p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–25 | 0–7.6 | 5.7 (5.4 –5.9) | 20.8 (50/241) | – |

| 25–50 | 7.6–12.1 | 6.3 (5.9 –6.7) | 26.1 (64/245) | 0.199 |

| 50–75 | 12.1–21.1 | 6.8 (6.4 –7.2) | 35.5 (87/245) | 0.001 |

| 75%– | 21.1– | 6.7 (6.3 –7.1) | 32.4 (79/244) | 0.005 |

*Severe cases were defined as TBscore ≥8.

†Fishers exact test comparing each stratum with baseline.

There was an increase in the proportion of severely ill patients as the delay increased and the association was significant (p=0.002) (table 3). There was no difference in TBscore between patients with a long and very long delay. The pooled percentage of severe TB cases for these two groups was 33.9%.

We also performed a logistic regression with severity ( TBscore ≥8) as the dependent variable and treatment delay (in 25th centiles) as the explanatory variable. This resulted in an OR=2.08 (95% CI 1.39 to 3.13) for the long delay stratum (7.6–12.1 weeks) and an OR=1.81 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.73) for the very long delay stratum (12.1–21.1 weeks). Correcting for possible confounders; HIV status, residential status, education, age and sex, the results were still significant—1.85 ((95% CI 1.21 to 2.82) and OR=1.57 ((95% CI 1.21 to 2.82), respectively.

In figure 1 we show the Kaplan-Meier mortality curves for the four delay quartiles. A delay above 21 weeks (quartile 4) had a higher mortality than quartile 1 (delay below 7.6 weeks), HR 1.59 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.48), whereas quartiles 2 and 3 did not differ significantly from quartile 1. The majority of excess mortality in people with a long treatment delay occurred after the first 6 months following presentation and when adjusting for HIV, age, education and civil status the HR was no longer significant (adjusted HR 1.10 (0.72 to 1.67)).

We included 343 smear-negative TB cases of whom 199 cases attended 6 months clinical follow-up after completion of anti-TB treatment. During treatment 36 died and the remaining 108 declined further clinical follow-up or were lost to follow-up. The mean TBscore for smear-negative TB cases decreased from 6.5 points to 1.3 points within 6 months of anti-TB treatment. The corresponding decrease in TBscore for smear positive patients was a decrease from a mean of 6.3 points to 0.9 points.

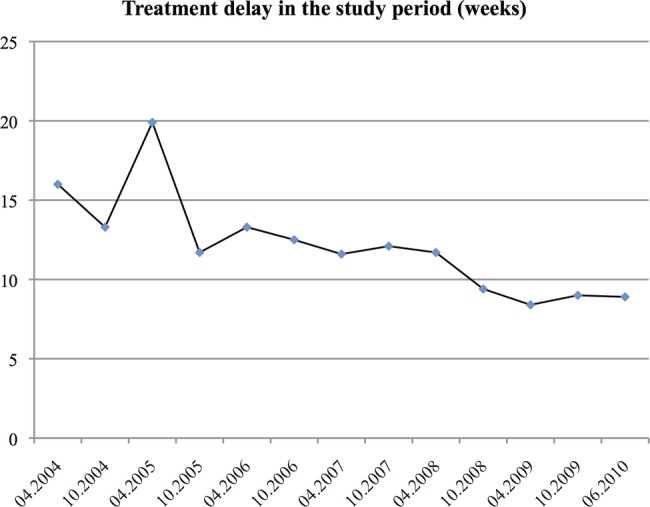

Changes in treatment delay

The median delay to treatment decreased during the study period. Within the first year the median delay was 14.6 weeks (IQR 9.3–26.1), but had dropped to 8.6 weeks (IQR: 5.7–16.7) in the last year of the study period. In a linear regression model the delay decreased by 10.3% (7.9–12.6%) annually. The delay decreased by 3 weeks from 12 weeks (n=153) to 9 weeks (n=110) in 2007 and 2008, respectively. The trend in delay is displayed in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Median treatment delay during the study period divided into 6 months intervals starting from November 2003. The last interval is 8 months to include all included cases in the figure.

To account for changes in other factors affecting treatment delay we adjusted for changes in the significant risk factors for treatment delay from table 2. This did not change the estimates significantly and the adjusted decrease was 8.5% (6.0–10.9%).

Discussion

This study showed a long treatment delay in the diagnosis of TB in Guinea-Bissau of 12.1 weeks equivalent to the delays found in comparable settings.21–25 We found a clear association between treatment delay and clinical severity at inclusion, which has not been described before. This association is not surprising as patients in whom delay was long, the disease had longer time to progress. We have shown in table 3 that the proportion of severely ill is higher among those with a long delay; in the long delay groups it is a third of patients who are severely ill compared with a fifth in the short delay group. This may translate into mortality risk; patients with a TBscore ≥8 have a 60% higher mortality risk as previously shown.18 and a sixfold higher risk of treatment failure,19 but in a multivariate model we were not able to show significance with this sample size. Furthermore, a higher risk of hospitalisation for patients with a longer treatment delay has also been described previously.26 The clinical implications of shorter treatment delay are therefore likely to be less severe TB and subsequent lower mortality as well as less time to infect others.

There was a significant difference in mortality between patients with a short delay, compared with those with a very long delay in the univariate analysis but when correcting for relevant factors this was no longer significant in the direct analysis.

The smear-negative cases had only 1 week longer median treatment delay than smear-positive cases and although transmission of disease is time dependent4 5 the community implications are probably limited.

We found that smear-negative patients profited substantially from anti-TB treatment. Although the diagnosis was not confirmed by culture or smear, an empirical 6 months anti-TB treatment resulted in a significant decrease in clinical severity assessed by TBscore.

Non-residential status did not reach statistical significance in the multiple regression model, although it could be due to a limited sample size. Non-residents are a heterogeneous group in our setting; some arrive with TB symptoms attending the centralised healthcare facilities. However, many come to work or study in the capital and acquire infection while being heavily exposed to TB living in an urban overpopulated environment. Previous studies have reported that residential status can be a risk factor for treatment delay8 9 and we suggest that this parameter is included in future studies.

HIV status influences treatment delay in some studies, but specific delay for HIV-1+HIV- 2 dual infection has not been described before. This could be a random finding but HIV-1+HIV- 2 dual infected cases are likely to be a vulnerable group with limited access to treatment. Furthermore, HIV-1+HIV-2 dual infected are more often sputum smear negative and present with fewer symptoms due to a weakened immune system.27

Several factors may influence the observed change over time in delay to treatment. Socioeconomic changes are likely to be the most important factors and the general economic situation in Bissau has improved in the past decade as the country has been rebuilt after the civil war in 1998.28 Changes in risk factors for delay during the study period could only explain a minor part of the decrease in treatment delay. We hypothesise that an increased awareness of signs and symptoms of TB may have been a factor after a TB prevalence survey in the study area in 2006 which may have contributed to the decrease in treatment delay.29 This survey among 2989 adults involved active case finding with the use of a questionnaire on TB symptoms and referral for sputum and X-ray according to an algorithm, and may have increased TB awareness in the involved 384 sampled houses. We have seen a peak in incidence in 2007 following this survey, which may have been a result of the survey and the increased awareness of TB in the study area.30

The study has several limitations; first, we were not able to divide treatment delay into patient-related and health system-related delay due to limited information on the first contact to any healthcare provider.

Second, recall bias is a potential problem although experienced local personnel and a comprehensive questionnaire were used,11 16 and the self-reported duration of symptoms may not be an accurate assessment of treatment delay. Patients were included after a considerable time period of symptomatic TB and may have overestimated the delay. The most invalidating symptoms present at inclusion may also have been overreported as a result of recall bias potentially influencing the reported symptoms analysis.

Third, we did not have data on the cause of death in the background population, and were not able to estimate the corresponding case detection rate (CDR) of pulmonary TB in the area. There may indeed be a small number of undiagnosed patients with TB who die from TB as previously shown.30 This is supported by our prevalence study finding undetected TB cases in the study area.29 Treatment delay may therefore have been underestimated since delay would be longer if undiagnosed cases with long delays had also been included.

Finally, this study was not a prospective follow-up of TB suspects and therefore we have no information on possible undetected TB cases or diagnosed yet untreated cases, and the study is therefore not able to assess how many patients with symptoms are under treatment. This has been carried out in a recent cohort study on TB suspects,31 but this is not the scope of this study.

Yet, our findings represent a population-based analysis over a long time period and are based on a large dataset. The results clearly show that delay in TB treatment is still a major issue in high burden areas. Our findings indicate that increased awareness of TB symptoms in the population and in healthcare systems is important to reduce the unacceptable long delay. Maintained focus is needed on awareness of TB and continuous implementation of TB control measures to detect the disease early and reduce unnecessary disability and loss of lives.

Conclusions

Delay of TB treatment in Bissau is significantly associated with disease severity at diagnosis. No education, HIV dual infection and smear-negative TB were significant risk factors for treatment delay. Treatment delay, although still unacceptably high, has decreased in Bissau during the past decade. TB control programmes may need to monitor treatment delay over time.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CW, FR and VG collected the clinical data. CC performed the laboratory tests. JV and AF checked all variables and JV wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PA, EP and CW made the study logistically possible and edited the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors thank the Aase og Ejnar Danielsen Foundation, Civilingenør Frode V. Nyegaard og Hustrus Foundation and Frimodt-Heineke Foundation for financial support for data collection. Danida Fellowship Center and Ulla og Mogens Folmer Andersens Foundation supported field visits at the Bandim Health project essential for this publication.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The National Science and Ethics Committee in Guinea-Bissau and The Central Ethics Committee of Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Tecnical appendix, statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, et al. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA 1999;282:677–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global tuberculosis control. WHO report 2013. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.USAID. Tuberculosis research to enhance the prevention, detection and management of TB cases. Washington, DC: USAID, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jochem K, Walley J. Determinants of the tuberculosis burden in populations. In: Porter JDH, Grange JM, eds. Tuberculosis: an interdisciplinary perspective. London: Imperial College Press, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golub JE, Bur S, Cronin WA, et al. Delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and tuberculosis transmission. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10:24–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Fact Sheet 104 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu B, Jiang QW, Xiu Y, et al. Diagnostic delays in access to tuberculosis care in counties with or without the National Tuberculosis Control Programme in rural China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:784–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sreeramareddy CT, Panduru KV, Menten J, et al. Time delays in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storla DG, Yimer S, Bjune GA. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health 2008;8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wandwalo ER, Morkve O. Delay in tuberculosis case-finding and treatment in Mwanza, Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:133–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lienhardt C, Rowley J, Manneh K, et al. Factors affecting time delay to treatment in a tuberculosis control programme in a sub-Saharan African country: the experience of The Gambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001;5:233–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pablos-Mendez A, Sterling TR, Frieden TR. The relationship between delayed or incomplete treatment and all-cause mortality in patients with tuberculosis. JAMA 1996;276:1223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harries AD, Graham S. TB/HIV: a clinical manual. Geneva: WHO Stop TB Initiative, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustafson P, Gomes VF, Vieira CS, et al. Tuberculosis in Bissau: incidence and risk factors in an urban community in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:163–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemvik GRF, Vieira F, Sodemann M, et al. Changes and trends in TB incidence in Guinea-Bissau. Helsinki: European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wejse C, Gomes VF, Rabna P, et al. Vitamin D as supplementary treatment for tuberculosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:843–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafson P, Gomes VF, Vieira CS, et al. Tuberculosis mortality during a civil war in Guinea-Bissau. JAMA 2001;286:599–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wejse C, Gustafson P, Nielsen J, et al. TBscore: Signs and symptoms from tuberculosis patients in a low-resource setting have predictive value and may be used to assess clinical course. Scand J Infect Dis 2008;40:111–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudolf F, Lemvik G, Abate E, et al. TBscore II: refining and validating a simple clinical score for treatment monitoring of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:825–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janols H, Abate E, Idh J, et al. Early treatment response evaluated by a clinical scoring system correlates with the prognosis of pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a prospective follow-up study. Scand J Infect Dis 2012;44:828–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngadaya ES, Mfinanga GS, Wandwalo ER, et al. Delay in tuberculosis case detection in Pwani region, Tanzania. A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steen TW, Mazonde GN. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Kweneng District, Botswana: delays in diagnosis in 212 smear-positive patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998;2:627–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yimer S, Bjune G, Alene G. Diagnostic and treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2005;5:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Needham DM, Foster SD, Tomlinson G, et al. Socio-economic, gender and health services factors affecting diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 2001;6:256–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ukwaja KN, Alobu I, Nweke CO, et al. Healthcare-seeking behavior, treatment delays and its determinants among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in rural Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawn SD, Afful B, Acheampong JW. Pulmonary tuberculosis: diagnostic delay in Ghanaian adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1998;2:635–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Getahun H, Kittikraisak W, Heilig CM, et al. Development of a standardized screening rule for tuberculosis in people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings: individual participant data meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The World Bank. World development indicators. Washington, DC: Development Data Group, The World Bank, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjerregaard-Andersen M, da Silva ZJ, Ravn P, et al. Tuberculosis burden in an urban population: a cross sectional tuberculosis survey from Guinea Bissau. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porskrog A, Bjerregaard-Andersen M, Oliveira I, et al. Enhanced tuberculosis identification through 1-month follow-up of smear-negative tuberculosis suspects. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:459–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolf F, Haraldsdottir TL, Mendes MS, et al. Can tuberculosis case finding among health-care seeking adults be improved? Observations from Bissau. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014;18:277–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.