Abstract

Background/Aims:

Despite the remarkable increase in the incidence of Crohn's disease among Saudis in recent years, data about Crohn's disease in Saudi Arabia are scarce. The aim of this study was to determine the clinical epidemiology and phenotypic characteristics of Crohn's disease in the central region of Saudi Arabia.

Patients and Methods:

A data registry, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Information System (IBDIS), was used to register Crohn's disease patients who presented to the gastroenterology clinics in four tertiary care centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between September 2009 and February 2013. Patients’ characteristics, disease location, behavior, age at diagnosis according to the Montreal classification, course of the disease, and extraintestinal manifestation were recorded.

Results:

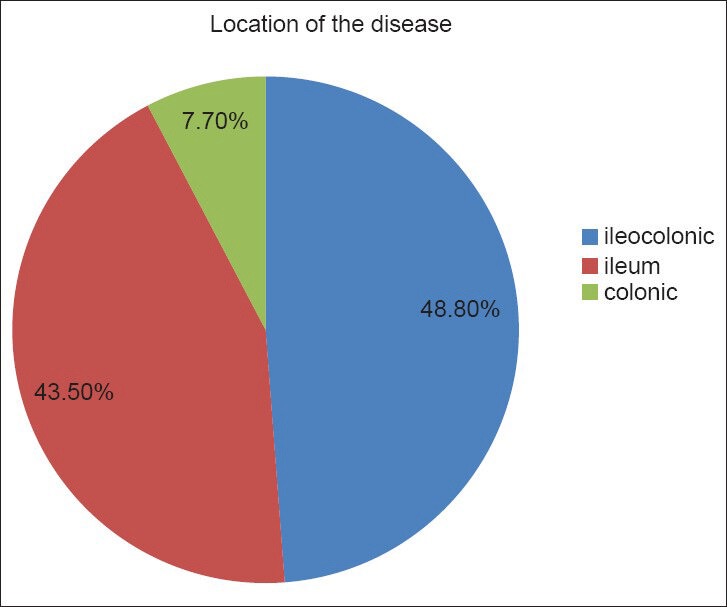

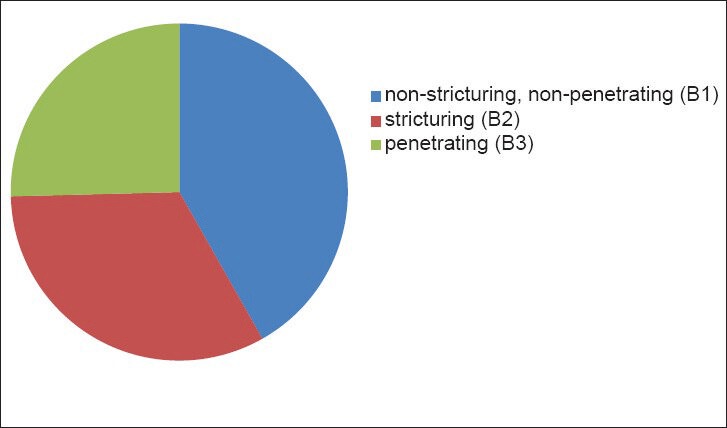

Among 497 patients with Crohn's disease, 59% were males with a mean age at diagnosis of 25 years [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 24-26, range 5-75 years]. The mean duration from the time of complaint to the day of the diagnosis was 11 months, and the mean duration of the disease from diagnosis to the day of entry to the registry was 40 months. Seventy-seven percent of our patients were aged 17-40 years at diagnosis, 16.8% were ≤16 years of age, and 6.6% were >40 years of age. According to the Montreal classification of disease location, 48.8% of patients had ileocolonic involvement, 43.5% had limited disease to the terminal ileum or cecum, 7.7% had isolated colonic involvement, and 16% had an upper gastrointestinal involvement. Forty-two percent of our patients had a non-stricturing, non-penetrating behavior, while 32.8% had stricturing disease and 25.4% had penetrating disease.

Conclusion:

Crohn's disease is frequently encountered in Saudi Arabia. The majority of patients are young people with a predilection for males, while its behavior resembled that of western societies in terms of age of onset, location, and behavior.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, epidemiology, Saudi Arabia

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of unknown etiology. Describing the epidemiology of IBD is important for appreciating the public health burden it causes and for planning appropriate health services for persons with IBD.[1,2] Moreover, careful descriptive epidemiological studies can offer clues to the etiology of these diseases.[3]

The incidence of IBD varies greatly worldwide. Western European and North American countries have been traditionally considered high-incidence areas. During the last decade, an increasing incidence rate has been observed in eastern Europe and Asia.[4,5,6] Although the data are still scarce, there is growing evidence that CD is being increasingly diagnosed in the Middle East.[7,8,9,10] Accurate classification of CD would be most helpful in this respect to allow an early assessment of the disease prognosis, thereby identifying and selecting patients for the most appropriate therapy according to the disease subtype.

Despite the increase in the incidence of CD observed among Saudis in recent years, there is very little data available about the characteristics of these patients as well as the course of the disease in Saudi Arabia.[7,11,12]

The aim of this study was to determine the clinical epidemiology and phenotypic characteristics of CD in the central region of Saudi Arabia using the Saudi IBD registry.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Saudi IBD epidemiology database

At the beginning of September 2009, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Information System (IBDIS)[13] was used to register all the IBD patients in one tertiary care center (King Khalid University Hospital), which was followed shortly by registration in three other centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Riyadh Military Hospital, Alhabeeb Medical Center, and Dallah Medical Center). IBDIS (www.ibdis.net) is a web-based documentation system comprising nine blocks that cover numerous aspects of IBD-related parameters. These include demographics, diagnosis, disease location and behavior, age at diagnosis according to the Montreal classification, course of the disease, extraintestinal manifestations, complications, risk factors, pregnancy, surgical and conservative therapy, which were all recorded in the registry.[13]

Patients

All patients with CD, who had presented to gastroenterology clinics or endoscopy units in the period between September 2009 and April 2013, had been interviewed and their clinical charts were screened by their attending physicians in addition to a trained research assistant who documented the information and directly incorporated it in the registry. All patients’ data had been updated on a regular basis (at every follow-up visit to the gastroenterology clinics). Given the inconsistency in reporting the features of the Montreal classification,[14] 10% of the data in the registry was randomly checked and validated by the investigators.

Disease phenotype

The Montreal classification was used to classify CD location [terminal ileal (L1), colonic (L2), ileocolonic (L3), and upper gastrointestinal (GI) (L4)] and disease behavior [non-stricturing, non-penetrating (B1), stricturing (B2), and penetrating (B3)].[15] Subjects with both stricturing and penetrating disease were classified as having penetrating disease (B3). Perianal fistulizing disease alone did not constitute penetrating disease, but was recorded as a modifier of the disease behavior (p). The location (L) and behavior (B) of the disease were considered cumulatively until the time of the most recent clinical assessment, endoscopic, histopathologic, and radiologic investigations, and surgical notes.

The course of the disease was assessed at the first time of inclusion and classified as: Infrequent relapser, ≤1 relapse per year; frequent relapser, >1 relapse per year; and chronic continuous activity, no remission throughout a year.[16] Perianal disease and behavior change during follow-up were also registered.

Case definition

The diagnosis of CD (based on standard clinical, endoscopic, radiologic, and histological criteria) was reviewed thoroughly using the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) guidelines.[17,18] Only those CD patients who had undergone a full colonoscopy with ileal intubation and biopsy (when not precluded by stenosis) were included in the study.

All patients gave informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at King Khalid University Hospital, with a site-specific approval from each participating hospital.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for continuous variables, means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values; for categorical variables, the frequencies were used. Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were estimated. We used STATA 11.2 (StataCorp, TX, USA) in our analysis. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients

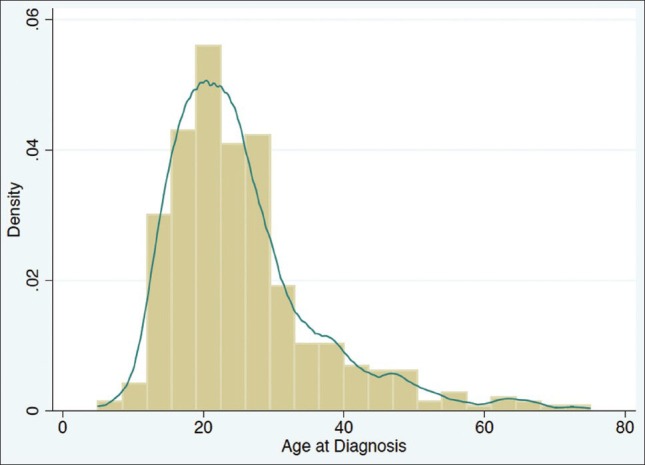

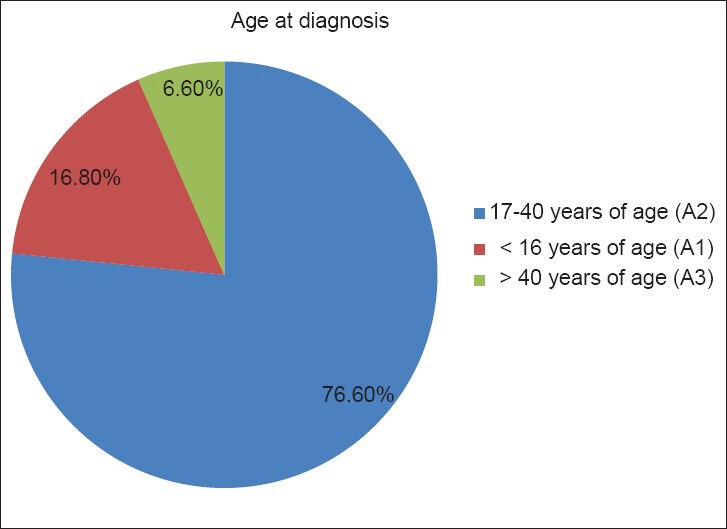

Among 497 Saudi patients, 58.6% were males and 41.4% were females, with a male to female ratio of 10 to 7 and a mean age at diagnosis of 25 years (95% CI: 24-26, range 5-75 years). The majority of patients were diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 30 years [Figure 1]. The mean duration from the time of the first complaint to the day of the diagnosis was 11 months and the mean duration of the disease from diagnosis to the day of registry was 40 months [Table 1]. There was a significant association between prolonged disease duration and stricturing disease behavior (P < 0.008), but not with penetrating behavior (P < 0.23). The distribution of the patients’ age at diagnosis according to sex and Montreal behavior classification showed no significant difference.

Figure 1.

Age at diagnosis of patients with Crohn's disease

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of CD patients

Twenty-eight patients (7%) (95% CI: 5-9) had a first-degree relative with CD, while eight patients (1.7%) (95% CI: 0.6-3) had a second-degree relative with CD. The mean C-reactive protein (CRP) level at data entry was 19.9 mg/L (95% CI: 16.3-23.6), with no significant association between the level of CRP and the disease behavior. Epithelioid cell granulomas (at least one found) were found in 22% of our patients (95% CI: 17.5-26). Forty-nine patients (9.9%) were active smokers, while 17 patients (3.4%) were ex-smokers. There was a significant association between smoking and penetrating disease behavior (P < 0.02), but not with stricturing disease behavior (P < 0.3).

Cutaneous involvement (mainly erythema nodosum and psoriasis) was observed in 5% of our patients (95% CI: 2.9-7.2), while ophthalmic manifestations (mainly episcleritis) were observed in 3.3% (95% CI: 1.4-5) and joint involvement was found in 15.5% (13.5% had arthralgia and 2% had arthritis). In addition, 2.3% of our patients (95% CI: 0.8-3.8) had developed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and one patient had developed primary sclerosing cholangitis. There was a significant association between the activity of the disease and the frequency of the DVT (P < 0.005).

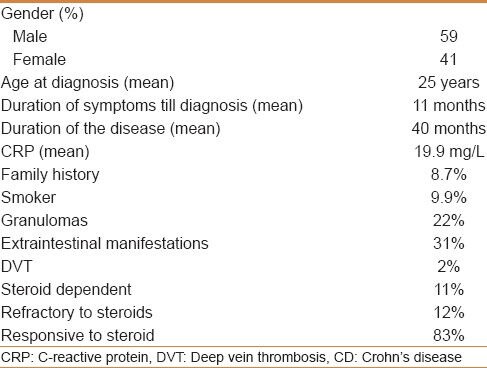

Disease localization and behavior

According to the Montreal classification, age at diagnosis was A2 (17-40 years of age) in 76.6% of our patients (95% CI: 72.5-80), A1 (≤16 years of age) in 16.8% (95% CI: 13-20), and A3 (>40 years of age) in 6.6% (95% CI: 4-9) patients [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Age at diagnosis according to the Montreal classification

According to the Montreal classification of CD location, 48.8% of patients (95% CI: 43.8-53.6) had ileocolonic involvement, 43.5% (95% CI: 38.6-48.4) had limited disease to the terminal ileum, and 7.7% (95% CI: 5-10) had involvement of the colon only; in addition, 15.6% (95% CI: 12-19) had upper GI involvement [Figure 3]. There was no significant difference in the disease behavior or location in relation to age at diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Location of the disease according to the Montreal classification

The disease behavior according to the Montreal classification was non-stricturing, non-penetrating in 41.8% of patients (95% CI: 37-46.6), stricturing in 32.8% (95% CI: 28.2-37.4), and penetrating in 25.4% patients (95% CI: 21.1-29.6) [Figure 4]. Patients with stricturing behavior were found to have more granulomas when compared to those with penetrating or those without stricturing or penetrating behavior (P = 0.002).

Figure 4.

Behavior of the disease according to the Montreal classification

A significant association was found between terminal ileal involvement and stricturing disease (P < 0.003), and between descending colon (P < 0.001), sigmoid (P < 0.005), and rectal disease (P < 0.006) involvement and penetrating behavior.

Perianal disease was present in 31.7% of patients (95% CI: 27.2-36.2) and perianal fistula was seen in 14% of patients; 66% of them were simple compared to 33% who had complex fistula. Perianal fistula was significantly (P < 0.003) found more in the A2 group (17-40 years of age) when compared to the A3 group (>40 years of age), and there was a significant association between the perianal disease and colonic involvement (P < 0.003).

The course of the disease upon the time of registration was as follows: 4% had chronic continuous activity (95% CI: 1.9-5.7), 18.5% had frequent relapses (95% CI: 14.7-22.4), and 77.7% had infrequent relapses (95% CI: 73.5-81.8). The disease course did not differ according to age or location of the disease (P values = 0.12 and 1.0, respectively), but patients with perianal fistulas were found to have an aggressive course when compared with those without (P < 0.004).

One hundred and thirty-nine patients (28%) underwent surgery, 35.7% had ileocecal resection, 14.3% had right-sided hemicolectomy, 13.3% had ileocecal resection or right-sided hemicolectomy in addition to segmental resection, while the remaining 36.7% underwent other surgical resections. The most common indications for surgery were stricture (48.4%) and fistula (35.5%).

Medications

Nineteen percent (95% CI: 15-24) had never been exposed to steroid, 47% (95% CI: 42-53) had been exposed to steroid once, 17% (95% CI: 13-21) had been exposed to steroid twice, 8% (95% CI: 5-10) had been exposed three times, and 9% (95% CI: 6-12) had received steroid more than three times. Five percent of the patients (95 CI: 2.5-7.6) were steroid dependent, 11.5% (95% CI: 7.8-15.3) were refractory to steroid, while 83.4% (95% CI: 78.9-88) were steroid responsive. Seventy-six percent of patients were on 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA; oral or local therapy), 60.2% were on azathioprine (299/497), given mainly for induction of remission (72.5%), while 1.4% were on methotrexate (7/497) and 32.2% were on biological therapy (160/497) (33.8% on adalimumab and 66.2% on infliximab).

DISCUSSION

Two decades ago, CD was considered very rare in the Middle East; but many recent reports from different centers in Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries suggest a surge of CD incidence and prevalence in the region.[7,8,9,10,11,19,20]

This study is the largest cohort and most comprehensive epidemiological study of CD in the Middle East, examining the clinical epidemiological data including CRP levels, age at diagnosis, duration of the disease, disease location, and behavior in 497 CD patients, according to the Montreal classification, in addition to a strict definition of CD based on the ECCO guidelines on CD definitions.[21]

There was a male predominance of the disease in our study, which is consistent with previous reports from Saudi Arabia and many other studies from the Middle East region,[7,9,11] although the difference was not as significant as reported in the Asian population.[22,23] In European and North American studies, the distribution of CD has consistently revealed a greater incidence in women than in men.[24] It is noteworthy that the most recent reports of incident pediatric CD reveal a male predominance.[3]

Age is an important predictor for CD, and a mean age of 25 years at diagnosis in our study is found to be less when compared to that reported in most of the studies published from Asia, Europe, and North America.[25] Most of the studies from the same region have not reported the mean age at diagnosis; instead they reported the mean age at the time of inclusion in the study. Our data showed only one peak in the age of onset of CD, occurring between 15 and 30 years, which is consistent with recent data.[26]

The short duration between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of CD (11 months), which is comparable with most of the recently published studies,[27,28] indicates the recent improvement of IBD awareness among both patients and physicians and the availability of diagnostic tests. A multicenter study from India has reported much longer median duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis (3 years) than what has been reported in most of the recent studies. The authors attributed this delay to the difficulty to differentiate from intestinal tuberculosis in India,[29] which was not an important factor in our cohort. In three consecutive population-based IBD cohorts from Copenhagen, Denmark, Jess et al. showed the time from the onset of symptoms to the diagnosis of CD decreased (P < 0.001) from 2.2 years in 1962-1987 to 0.7 years in 2003-2004.[27] There was a significant association between the longer duration of the disease and the stricturing disease behavior, but not with the penetrating behavior in our cohort. Over 10 years of follow-up, Louis et al. found that 45.9% of patients had a change in disease behavior.[30]

In population-based studies, approximately 5-10% of all affected individuals with IBD reported a positive family history,[31] which is consistent with our findings (8.7%). The familial clustering appears to be less common in the Far East compared to the West.[32]

Most of our CD patients had an elevated CRP level at the day of entry to the registry, with a mean of 19.9 mg/L, which correlates well with the disease activity.[33] A study by Shine et al. showed an increased CRP was able to differentiate all IBD cases from patients with functional bowel disorders.[34] Although the prevalence of active smokers was low in our cohort (10%) compared to that in the general Saudi population (17.5%), the prevalence of current smoking among young Saudis (university students) was lower than among the elderly (13.5% vs. 25%),[35] which, in addition to quitting smoking due to their disease, might explain the low frequency of smoking among our CD patients. We found a significant association between active smoking and penetrating disease behavior, but not with stricturing disease behavior, a finding which is consistent with that of Louis et al.'s study where they found that active smoking was associated with a penetrating pattern compared with a non-stricturing, non-penetrating pattern only.[36]

In our study, the granulomas in biopsy specimens (22%) were consistent with most published studies and were more frequently seen in patients with stricturing behavior.[37] A study from China demonstrated that granulomas were associated with a stricture-forming phenotype of CD.[38]

Thirty-one percent of our patients were found to have or have had extraintestinal diseases. Similar to previously published studies, arthralgia/arthritis followed by erythema nodosum and episcleritis were the most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations.[39]

In our study, thromboembolism occurred in CD patients at a rate of 2%, which is higher than that reported in the literature. Saleh et al. reported that the incidence of venous thromboembolism among the CD patients discharged from hospitals throughout the United States was 1.22%.[40] Similarly, we found a significant association between the severity of the disease and the frequency of DVT in our patients, which is consistent with that reported in the literature.[41]

According to the Montreal classification, the majority of our patients (76.6%) were A2 (17-40 years of age). Seventeen percent of our patients were younger than 17 years (A1), compared to about 2% in China and 8% in southern Europe. Similarly, the proportion of patients diagnosed at age >40 years (A3) in our study was only 6.6%, compared to 19% in southern Europe and 25% in China.[42,43] One of the possible reasons is that most of our patients were relatively newly diagnosed; in addition, pediatric cases (below 13 years of age) were not enrolled.

According to the Montreal classification, the majority of our patients had ileocolonic involvement (48.8%), with only 7.7% confined to the colon, while most had a non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease behavior (41.8%). The distribution of location in CD is relatively stable and evenly distributed across the published literature.[27] Whereas the anatomical location was mostly stable,[44] the behavior of CD, according to the Montreal classification, substantially varied during the course of the disease.[45,46]

There was no significant difference in the disease behavior or location in relation to age at diagnosis, but there was a significant association between terminal ileal involvement and stricturing disease, and between descending colon, sigmoid, and rectal disease involvement and penetrating behavior. A positive association between disease location and behavior was found previously in the original description of the Vienna classification;[47] in addition, Louis et al. found an association between isolated small bowel disease (L1) and stricturing disease (B2), and between colonic disease (L2) and penetrating behavior (B3).[30]

Almost one-third of our cohort had or have perianal disease and 14% had or have fistulae, which is consistent with most of the published data from the western countries (20-30% and 15-20%, respectively).[26,48] We found a significant association between the perianal disease and colonic involvement, which was also found in other studies. In patients with CD in Olmsted County, Minnesota, the risk of perianal fistula in patients with colonic disease was twofold higher than in patients with ileal disease.[49] In addition, we found that perianal fistula was significantly (P value 0.003) associated with A2 group (17-40 years) when compared to A3 group (>40 years).

Most of our patients had infrequent relapses (77.7%), 18.5% had frequent relapses, and 3.8% had chronic continuous activity. In North America, after the first year of diagnosis, 10-30% of patients have an exacerbation, 15-25% have low activity, and 55-65% are in remission; 13-20% have a chronic active course of disease activity, 67-73% have a chronic intermittent course, and only 10-13% remain in remission for several years.[50,51]

Five percent of our patients were steroid dependent, 11.5% were refractory to steroid, while 83.4% were steroid responsive; in addition, 19% of our patients had never been exposed to steroid, 47% had been exposed to steroid once, 17% twice, 8% three times, and 9% had received steroid more than three times at the time of data entry to the registry. Among 196 Danish patients diagnosed with CD, after a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 56% had received at least one systemic steroid treatment course, 48% achieved clinical remission, 32% had partial clinical response, and 20% did not respond to corticosteroid therapy. At the end of follow-up, 44% had prolonged steroid response, 36% were steroid dependent, and 20% were steroid resistant,[52] which is higher than the rate of steroid dependence (5.1%) reported in our cohort.

Seventy-six of our patients were on 5-ASA, 60.2% were on azathioprine (299/497), while 1.4% of them were on methotrexate (7/497). Thirty-two percent of our cohort was on biological therapy (160/497), 33.8% on adalimumab, and 66.2% was on infliximab, which is consistent with most of the reported studies.[53]

Although this is not a population-based study, the advantage of this cross-sectional prospective study is the large number of patients with definite CD from four centers in an area, which was not known, until recently, to have this surge of IBD patients.

In conclusion, CD is frequently encountered in Saudi Arabia. The majority of CD patients were men and diagnosed at a younger age, and the disease resembled that of western societies in terms of age of onset, disease location, and behavior, based on the Montreal classification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project is supported by College of Medicine Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for its funding of this research through the Research Group Project number RGP-VPP-279

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Wajda A. Epidemiology Of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in a Central Canadian Province: A population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:916–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay JW, Hay AR. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Costs-of-illness. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:309–17. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, Mackenzie A, Koehoorn M, Jackson M, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease In Canada: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1559–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jussila A, Virta LJ, Kautiainen H, Rekiaro M, Nieminen U, Farkkila MA. Increasing incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases between 2000 And 2007: A Nationwide register study in Finland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:555–61. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thia KT, Loftus EV, Jr, Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3167–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sincic BM, Vucelic B, Persic M, Brncic N, Erzen DJ, Radakovic B, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Primorsko-Goranska County, Croatia, 2000-2004: A prospective population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:437–44. doi: 10.1080/00365520500320094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Ghamdi AS, Al-Mofleh IA, Al-Rashed RS, Al-Amri SM, Aljebreen AM, Isnani AC, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of Crohn's Disease in a teaching hospital in Riyadh. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1341–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddique I, Alazmi W, Al-Ali J, Al-Fadli A, Alateeqi N, Memon A, et al. Clinical epidemiology of Crohn's Disease in Arabs based on the Montreal classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1689–97. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdul-Baki H, Elhajj I, El-Zahabi LM, Azar C, Aoun E, Zantout H, et al. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory Bowel Disease in Lebanon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:475–80. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, Firouzi F. Inflammatory Bowel disease in Iran: A Review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1691–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadda MA, Peedikayil MC, Kagevi I, Kahtani KA, Ben AA, Al HI, et al. Inflammatory Bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: A hospital-based clinical study of 312 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:276–82. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Mouzan MI, Al Mofarreh MA, Assiri AM, Hamid YH, Al Jebreen AM, Azzam NA. Presenting features of childhood-onset inflammatory Bowel Disease in the central region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:423–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oefferlbauer AM, Eckmuellner O, Gangl A, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W. Interobserver agreement analysis of a national INFLAMMATORY Bowel Disease Information System (IBDIS) Gastroenterology. 2003;124(4 Suppl 1):A507. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnaprasad K, Andrews JM, Lawrance IC, Florin T, Gearry RB, Leong RW, et al. Inter-observer agreement for Crohn's Disease Sub-Phenotypes using the montreal classification: How good are we? A Multi-Centre Australasian study. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5–36. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Beglinger C, Kupcinkas L, Geboes K, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's Disease: Definitions and diagnosis. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 1):I1–15. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2–6. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, Van Der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's Disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63–101. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Mouzan MI, Abdullah AM, Al Habbal MT. Epidemiology of JUVENILE-ONSET Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Central Saudi Arabia. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:69–71. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi039. Al-Mofarreh MA, Al Mofleh IA, Al-Teimi IN, Al-Jebreen AM Crohn’s Disease in a Saudi outpatient population: Is it still rare Saudi J Gastroenterol 2009;15:111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Mofarreh MA, Al Mofleh IA, Al-Teimi IN, Al-Jebreen AM. Crohn's disease in a Saudi outpatient population: is it still rare? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:111–6. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.45357. Epub 2009/07/02 doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.45357 PubMed PMID: 19568575; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2702976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, Allez M, et al. The second European Evidence-Based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's Disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:7–27. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leong RW, Lau JY, Sung JJ. The epidemiology and phenotype of Crohn's Disease in The Chinese Population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:646–51. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahuja V, Tandon RK. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Asia-Pacific Area: A comparison with developed countries and regional differences. J Dig Dis. 2010;11:134–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loftus EV, Jr, Sandborn WJ. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(01)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker DG, Williams HR, Kane SP, Mawdsley JE, Arnold J, Mcneil I, et al. Differences in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype between South Asians and Northern Europeans living in North West London, UK. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1281–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, Winther KV, Borg S, Binder V, et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: A population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:481–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loftus EV, Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn's Disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: Incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1161–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das K, Ghoshal UC, Dhali GK, Benjamin J, Ahuja V, Makharia GK. Crohn's Disease in India: A multicenter study from a country where tuberculosis is endemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1099–107. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn's Disease according to the Vienna classification: Changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut. 2001;49:777–82. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.6.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonen DK, Cho JH. The genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:521–36. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheon JH. Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A comparison between western and eastern perspectives. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:220–6. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. C-reactive protein as a marker for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:661–5. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shine B, Berghouse L, Jones JE, Landon J. C-reactive protein as an aid in the differentiation of functional and Inflammatory Bowel Disorders. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;148:105–9. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(85)90219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassiony MM. Smoking in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:876–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louis E, Michel V, Hugot JP, Reenaers C, Fontaine F, Delforge M, et al. Early development of stricturing or penetrating pattern in Crohn's Disease is influenced by disease location, number of flares, and smoking but not by NOD2/CARD15 Genotype. Gut. 2003;52:552–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almadi MA, Aljebreen AM, Sanai FM, Marcus V, Almeghaiseeb ES, Ghosh S. New insights into gastrointestinal and hepatic granulomatous disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:455–66. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leong RW, Lawrance IC, Chow DK, To KF, Lau JY, Wu J, et al. Association of intestinal granulomas with smoking, phenotype, and serology in Chinese patients with Crohn's Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1024–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. Long-term complications, extraintestinal manifestations, and mortality in Adult Crohn's Disease in population-based cohorts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:471–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh T, Matta F, Yaekoub AY, Danescu S, Stein PD. Risk of venous thromboembolism with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011;17:254–8. doi: 10.1177/1076029609360528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murthy SK, Nguyen GC. Venous thromboembolism in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An epidemiological review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:713–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magro F, Portela F, Lago P, Ramos De Deus J, Vieira A, Peixe P, et al. Crohn's Disease in a Southern European Country: Montreal classification and clinical activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1343–50. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chow DK, Leong RW, Lai LH, Wong GL, Leung WK, Chan FK, et al. Changes in crohn's disease phenotype over time in the Chinese Population: Validation of the montreal classification system. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:536–41. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of adult Crohn's Disease in population-based cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:289–97. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thia KT, Sandborn WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV., Jr Risk factors associated with progression to intestinal complications of Crohn's Disease in a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1147–55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's Disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D’Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, et al. A simple classification of Crohn's Disease: Report of the working party for the world congresses of gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Perianal Crohn's Disease: Classification and clinical evaluation. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:959–62. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sachar DB, Bodian CA, Goldstein ES, Present DH, Bayless TM, Picco M, et al. Is Perianal Crohn's Disease associated with intestinal fistulization? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1547–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loftus EV, Jr, Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn's Disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: A systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in Crohn's Disease. Gut. 1994;35:360–2. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rungoe C, Langholz E, Andersson M, Basit S, Nielsen NM, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Changes in medical treatment and surgery rates in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide cohort study 1979-2011. Gut. 2013 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305607. Epub 2013/09/24 Doi: 10.1136/Gutjnl-2013-305607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]