Abstract

Purpose:

This research was done to assess levels of psychosocial stress and related hazards [(burnout, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)] among emergency medical responders (EMRs).

Materials and Methods:

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted upon (140) EMRs and a comparative group composed of (140) nonemergency workers. The groups studied were subjected to semistructured questionnaire including demographic data, survey for job stressors, Maslach burn out inventory (MBI), Beck depression inventory (BDI), and Davidson Trauma scale for PTSD.

Results:

The most severe acute stressors among EMRs were dealing with traumatic events (88.57%), followed by dealing with serious accidents (87.8%) and young victims (87.14%). Chronic stressors were more commonly reported among EMRs with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) except for social support with colleagues and supervisors. EMRs had statistically significant higher levels of emotional exhaustion (EE) (20%) and depersonalization (DP) (9.3%) compared with comparative group (4.3%, 1.4% respectively). Also, there was no statistically significant difference between two groups as regards lower personal achievement or depression symptoms (P > 0.05). There was increased risk of PTSD for those who had higher stress levels from death of colleagues [odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] = 2.2 (0.7-7.6), exposure to verbal or physical assault OR (95% CI) = 1.6 (0.5-4.4) and dealing with psychiatric OR (95% CI) 1.4 (0.53.7) (P > 0.05)

Conclusion:

EMRs group had more frequent exposure to both acute and chronic work-related stressors than comparative group. Also, EMRs had higher levels of EE, DP, and PTSD compared with comparative group. EMRs are in need for stress management program for prevention these of stress related hazards on health and work performance.

Keywords: Burnout, depression, emergency medical responders, post-traumatic stress disorders, psychosocial stress among emergency medical responders, work-related stress among ambulance workers

Introduction

Until recently, occupational health within the ambulance services has received relatively little attention from researchers. In the past few years, researchers have become increasingly aware that ambulance personnel may be at risk of developing work-related health problems.(1,2)

No study has systematically compared the level of symptoms and prevalence of cases between ambulance workers and the normative sample of a relevant working population. Previous research comparing the health status in ambulance personnel with that of general populations has not considered the healthy worker effect.(3)

In the field of occupational health psychology, researchers have mostly focused their attention on negative effects of long-term work characteristics, in particular chronic work-related stressors, such as job overload, shift work, role conflict, and lack of social support. Implications of these sources of work-related stress include the effects on worker satisfaction and productivity, mental as well as physical health, absenteeism, and the potential for employer liability. However, the role of acute and intense stressors is often neglected.(4)

Exposure to traumatic stressors is potentially integral part of the job for emergency service personnel. Traumatic stressors, or critical incidents, are those in which personnel are exposed to death or life-threatening injury. In addition to the risk of mortality,(5) serious mental health and behavioural problems are associated with such traumatic exposure. These include posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression.(1)

Burnout and stress are common-related problems in health service workers.(6) Maslach and Jackson(7) defined burnout as a physical, emotional, and intellectual exhaustion syndrome manifested by adverse attitude to professional life and other people with the development of a negative self-esteem in the individual experiencing chronic fatigue and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness.

This research was done to assess the possibility for higher levels of psychosocial stressors and related hazards (burnout, depression, and PTSD) among emergency medical responders (EMRs) compared with comparative group.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted over a period from June 1, 2011 to August 31, 2012 upon EMR and a matched comparative group at Mansoura city.

Study population

The study population comprised (280) subjects employed in main ambulance service at Mansoura city. They were divided into two groups: EMR group which consisted of 140 responders and comparative group which consisted of 140 nonemergency workers.

EMRs group

Inclusion criteria

Permanent and temporary male EMRs employed for more than 1 year working either in main center in Mansoura city, urban and rural units. One hundred and forty EMR were randomly selected after approval to participate in the present study. They were all males. Their ages ranged from 22-58 years with a mean age of 37 ± 9.35 years. The mean duration of employment was 11.2 ± 9.9 years. This group consisted of 80 EMTs and 60 emergency drivers.

Job description of EMRs

Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) are emergency responders trained to provide immediate care for sick or injured people and transport them to medical facilities. They usually work as team of two responders (EMT and driver) and may request additional assistance from the police or fire departments. The emergency driver drives an ambulance to transport sick, injured, or convalescent persons to/from a hospital or other health facility and performs various duties related to this main job such as carrying; cleaning; communicating; handling; and lifting.(8)

Most of EMTs and drivers are required to work 24 h a day every other day. There are two types of shifts in Mansoura ambulance service either 24 h day after day shift or daily 8 h shift rotating between day, evening, and night shifts.

Comparative group

The group comprised 140 male workers at Mansoura's main ambulance center, technical institute of health, and faculty of Commerce and faculty of Medicine at Mansoura University, who matched EMRs in most of the variables except for the risk of exposure to stressful job situation due to emergency work. They were all males. Their ages ranged from 22 to 59 years with a mean age of 39.5 ± 11years. The mean duration of employment was 13.5 ± 9.9 years.

Job description of comparative group

They are service and office workers in Mansoura ambulance center who never worked in providing emergency medical service. Service workers ensure that building and offices are maintained in a clean and orderly manner. Office workers from ambulance center carry out technical and maintenance jobs, accountant service, and financial affairs. Service workers included laboratory and maintenance technicians in Mansoura faculty of medicine, Mansoura faculty of commerce, and technical institute of health.

Methods

An interview with each study subject was carried out to help filling in the questionnaire and direct observation of psychosocial-work environment.

Questionnaire

A semistructured questionnaire was designed to obtain sociodemographic data including age, sex, residence, lifestyle (such as smoking and illicit drug abuse), occupational history [job description, duration of employment, shift work hours, job stress survey (frequency and types]for acute stressors in the form of dealing with psychiatric patients, dying patients, young victims.(4) The responders were asked to rate how stressful was these stressors on a scale from1 (not stressful) to 4 (extremely stressful). Questions about chronic work-related stressors according to questionnaire on the experience and assessment of work were included in the form of lack of job autonomy; lack of social support from colleagues and supervisors.(9)

Psychosocial health hazards assessment tools

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

Burnout was assessed according to the MBI. This instrument contains 22 items that measure the cumulative effects of work-related pressure on three states: “Emotional exhaustion (EE), DP,” and “personal accomplishment (PA).” Each question is assessed on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (yes, absolutely). High scores for the first two scales and low scores for the last scale are associated with burnout.(10)

Beck depression inventory “Arabic version”

Depression was assessed according to Beck depression inventory (BDI) “Arabic version.” This instrument contain 21 questions each item is rated on a FOUR-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. The maximum total score is 63.(11)

Davidson trauma scale (DTS) (DSM-IV) (Arabic form)

All study subjects completed the DTS, a 17-item scale measuring each Diagnostic and statistical manual-IV symptom of PTSD on five-point frequency and severity scales. The subjects were diagnosed with PTSD symptoms when having one of the re experience or recall symptoms, three avoidance symptoms, and one of the arousal symptoms (Arab corporation for psychological test 2010).(12)

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 16 for Windows. The normality data were first tested with one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics, mean, median were calculated to describe central tendencies in each group. The groups were compared with Student's t test for continuous parametric variables and Man-Whitney test (z) for nonparametric continuous variables. Chi-square (χ2) test was used for categorical variables. Fisher's exact test was used when 50% of cells or more were less than 5; P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

Approval of related authorities including the regional ambulance head manager, faculty of Medicine, faculty of commerce, and technical school of health was obtained. Also, an informed verbal consent from each study subject to participate in the study was obtained before the start of work with assurance of confidentiality and anonymity of the data. Subjects were requested personally by the investigator and they were asked to participate voluntarily with a full right to withdraw from the study.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of studied groups

The EMRs group-matched comparative group as regards all sociodemographic variables. The mean age of EMRs group and comparative group was 38 ± 9.4 and 39.5 ± 11.5 respectively. Both groups were males. The majority of EMR and comparative group were from rural area respectively (60%, 54.3%) and married (81.4%, 82.9%). Also, most of studied EMRs and comparativegroup had received technical education (61.4%, 48.6%). (Data are not tabulated).

Job characteristics of studied groups

The EMRs group composed of eighty EMT (57.1%) and 60 drivers (42.9%), while the comparative group composed of 61 administration staff members (43.6%) and 79 service workers (56.4%). About half of EMR group (52.9%) were hired with short contracts, while most of comparative group subjects (72.1%) were permanent workers with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). The mean duration of employment was 11 ± 9.9 for EMR, while the mean duration of employment for comparative group was 13.3 ± 9.8 with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). Also, it was observed that most of EMR (68.6%) were 24 h shift workers and most of comparative subjects (47.1%) were day workers (≤8 h) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) (Data are not tabulated).

Acute stressors

EMR suffered from different acute job stressors. The most severe acute stressors was dealing with traumatic events (88.57%), followed by dealing with serious accidents (87.8%) and young victims (87.14%). Dealing with psychological patient was the least frequently encountered acute stressor (45.7%) (Data are not tabulated).

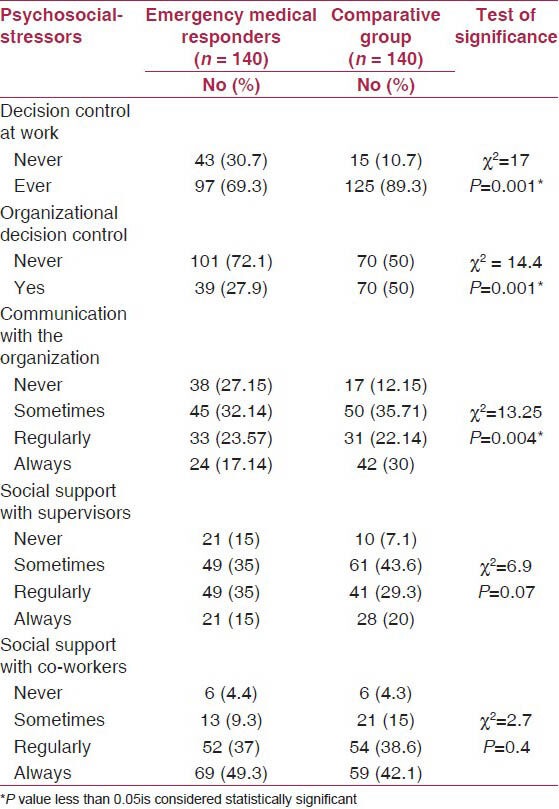

Chronic organizational stressors

EMR group experienced exposure to overall job stressors with different degrees more frequently (100%) than comparative group (56.4%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Also, lack of decision control at work and lack of organizational decision control were more commonly reported (30.7%, 72.1%) among EMR compared with comparative group (10.7%, 50%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). EMRs group reported poorer communication with their organization (27.1%) than comparative group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Also, social support with supervisors among EMRs (85%) was less than that reported by comparative group (92%) with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). In addition, social support with co-workers was (95.6%) among EMRs compared with 95.9% among the comparative group with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). EMRs had higher levels of group moral and cohesion (98.6%) compared with comparative group (93.6%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Frequency of chronic organizational psychosocial stressors among studied groups

EMRs had significantly higher percentage of physically strenuous activities, rapid pace of work, overtime work, work overload, never receiving compensatory financial rewards, and lower percentage for reporting enough resources than comparative group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) (Data are not tabulated).

Burnout

EMR had higher levels of EE (20%) compared with comparative group (4.3%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Also, DP levels were higher among EMR (9.3%) compared with comparative group (1.4%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). However, high personal achievement was more frequently found in EMRs group (80.7%) than that found in comparative group (74.3%) with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Levels of burnout subscales among study groups according to Maslach burnout inventory

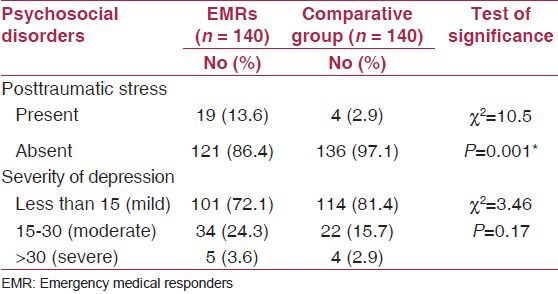

Depression and PTSDs

Total BDI score and depression grade was not significantly different among EMR when compared with comparative group (P > 0.05). Median total score of Davidson scale for PTSD was higher among EMR (5) compared with comparative group (0) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Also, 13.6% of EMRs had PTSD compared with (2.9%) of comparative group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms among studied groups

Risk factors for PTSDs

There was no statistically significant difference between EMR with PTSD and EMR without PTSD as regard exposure to acute stressors (P > 0.05). In the mean, while there was increased risk of PTSD for those who had higher stress levels from death of colleagues (OR) (95% CI) = 2.2 (0.7-7.6), exposure to verbal or physical assault OR (95% CI) = 1.6 (0.5-4.4), and dealing with psychiatric OR (95% CI) = 1.4 (0.5-3.7) (Data are not tabulated).

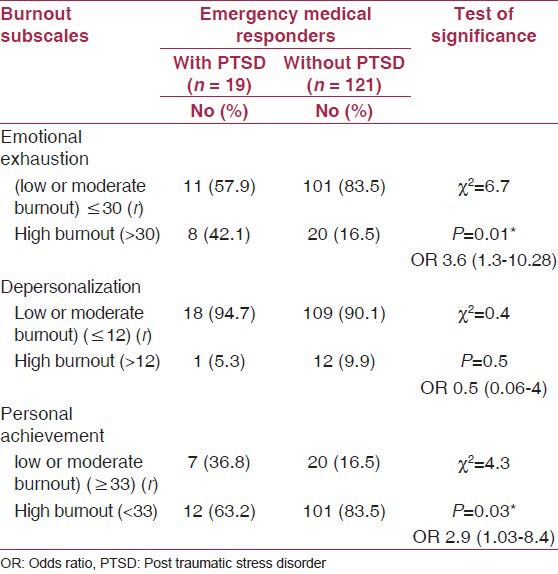

Impact of burnout on PTSD among EMRs

EE levels among EMR with PTSD were significantly higher (42.1%) than those without PTSD (16.5%) (P < 0.05) OR (3.6) (95% CI: 1.3-10.28). Moreover, higher personal achievement was more common among responders with PTSD (36.8%) compared with those without PTSD (16.5%) with OR (2.9) (95% CI: 1.03-8.4) (P < 0.05). However, DP was more frequent (9.9%) among responders with no PTSD compared with (5.3%) of EMR with PTSD with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) [Table 4]. Logistic regression analysis showed that EE was independently associated with the likelihood of having posttraumatic stress symptoms (OR = 4.6) (Data are not tabulated).

Table 4.

Impact of burnout on posttraumatic stress disorder among emergency medical responders

Discussion

Emergency responders, including EMS personnel, fire fighters, and law enforcement officers, risk their health, and safety to assist in medical emergencies; motor vehicle incidents; building and wild-land fires; hazardous material spills; crimes and public disturbances; search and rescue; and natural and human-caused disasters.(13)

Current study results demonstrated that EMR group experienced exposure to acute and chronic job stressors with different degrees more frequently (100%) than comparative group (56.4%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Ambulance specific stressors were reported as significantly more severe than the general organizational stressors. Serious operational demands were reported as the most severe stressor(14,15) and physical demands were the second most severe stressor.(14,16)

In current research, severity of acute ambulance specific stressors and frequency of general chronic stressors were assessed. It was found that EMRs suffered from different acute job stressors. The most severely encountered acute stressors was dealing with traumatic events (88.57%), followed by dealing with serious accidents (87.8%) and young victims (87.14%). Dealing with psychological patient was the least frequently encountered acute stressor (45.7%).

In accordance with our hypotheses, ambulance-specific stressors were identified as the most severe stressors. Serious operational tasks, and the items ‘dealing with seriously injured friends and people you know’ and ‘dealing with seriously injured children’ in particular, were rated as the most severe stressor (a higher mean score than the two general stressors time pressure and challenging job tasks).(17)

In current study, the frequency of chronic organizational stressors was assessed, rapid pace of work was the most frequently reported organizational stressor among EMR group (96.3%), followed by physical strain (95.3%), work-overload (83.6%), and overtime work (62.1%) compared with comparison group (45%, 68.7%, 57.9%, and 8.6%), respectively with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

These results were in accordance with Stured et al.,(17) who reported that physical demands were the most frequent stressors and second most severe compared to all other stressors. The authors explained their finding by much heavy lifting and carrying under difficult conditions. In addition, this concurs with other studies, which have found that ambulance personnel report higher levels of musculoskeletal strain than employees in other health services,(4) and that ambulance personnel self-report more musculoskeletal and physical health problems than the general population.(18,19)

These results were consistent with Ploeg and Kleber(4) who reported that ambulance workers scored higher than reference group, which meant that they reported more chronic work related stressors.

Moreover, EMRs at Mansoura reported poorer communication with their organization (27.1%) than comparison group (12.1%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). These results came in agreement with similar study in Netherland that reported significantly higher mean levels of poor communication among ambulance workers compared to reference group.(4)

Also, social support with supervisors among EMR (85%) was less than that reported by comparative group (92%) with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). In addition, social support with co-workers was (95.6%) among EMR compared 95.9% among the comparison group with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). EMR had higher levels of group moral and cohesion (98.6%) compared with comparative group (93.6%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

It was noticed that the levels of social support with supervisors and co-workers in current study were satisfactory in comparison to Stured et al.,(17) who reported that lack of social support from co-worker and leaders was the second most frequent stressor after physical demand and most severe general stressors. Moreover, Ploeg and Kleber(4) reported higher mean levels for lack of social support from colleagues and supervisors among ambulance workers compared with reference group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.001).

Frank and Ovens(20) have pointed to the fact that emergency work is both rewarding and demanding in that little control over patient-mix exists, compounded by the fact that life and death decisions have to be made quickly.

The current research revealed that lack of decision control at work and lack of organizational decision control were more commonly reported (30.7%, 72.1%) among EMRs compared with comparative group (10.7%, 50%) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

Ploeg and Kleber(4) reported higher mean levels for lack of job autonomy among ambulance workers than reference group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.001).

Alexander and Klein(21) reported indeed high levels of job satisfaction among ambulance workers. However, a distinction between satisfaction with regard to the job and satisfaction with regard to the organization can be made. Expressed job satisfaction does not mean that the organization does not have to concern about the well-being of its employees. Dissatisfaction with organizational aspects has a price: A price to be measured in terms of the levels of general psychopathology, burnout, and posttraumatic symptoms. Current study results revealed that lack of organizational decision control among EMRs can be important source for organizational dissatisfaction and psychopathological diseases among studied population.

The levels of burnout subscales in the form of EE and DP were higher among EMR compared with comparison group with statistically significant difference (P > 0.001). The percentage of the workers with high score on separate subscales were (20%) for EE, 9.3% for DP, and 19.3% for low PA.

A study from the Netherlands Ploeg and Kleber(4) used the MBI to investigate the prevalence of burnout in workers from 10 regions and found a higher risk for burnout in ambulance workers (8.6%) than in the general working population (5.3%). The percentages of workers with high scores on the separate dimensions were reported as 12% for EE, 18% for DP, and 16% for low PA.

However, a study from a single service in the USA reported an opposite result and concluded that the average burnout scores in ambulance workers were slightly but not significantly lower than the national average.(22) However, this conclusion was based on a small and non-representative sample. A study from a Scottish regional ambulance service reported the percentages of workers with high scores on the MBI for the separate scales as 26% for EE, 36% for low PA, and 22% for DP, but did not report confidence intervals.(21)

Our research results have reported comparable levels of depression symptoms according to BDI among EMR and comparative group. The prevalence of depression was 3.6% among EMRs compared with 2.9% among comparative group with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). A lower prevalence (2.1%) of severe symptoms, as measured with BDI, was reported in a study from a single ambulance service in Canada.(23) Three other studies reported a similarly high prevalence of psychological distress (>20%), as measured by the General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-12].(21,24,25)

Median total score of Davidson scale for PTSD was higher among EMR (5) compared with comparative group (0) with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Also, 13.6% of EMRs had PTSD compared with (2.9%) of comparative group with statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

The prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms was also high in some studies(1,26,27) although these studies used different scale for evaluation of PTSD. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, particularly because the high PTSD symptom scores in the ambulance services might reflect that, when asked to report on a traumatic incident, ambulance workers may have a larger reservoir of potentially traumatic memories to choose from than the general population. Hence, ambulance personnel may score much higher on the PTSD scales than the general population without necessarily having more actual problems. Therefore, more research should focus on sleeping problems, intrusion, and hyperarousal among ambulance personnel.(15)

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are first, the ability to compare the frequency of psychosocial hazards with a sample of working population as control group. Most of previous studies focused on emergency workers only or compared with general population which is different from working healthy population. Second, there is little public awareness that EMTs’ job is the host of many occupational hazards especially in developing countries. Third, burnout and depression among EMRs are still an open question due to conflicting results reported by previous studies. Limitations of current study included convenient sample of EMRs which can be attributed to limited time for data collection on work day for all responders who work day after day. Another aspect that can be investigated in further research is drug abuse as a consequence of job stress especially among emergency drivers. Moreover, no clear delineation was reported in current research as regards cause-effect relationship between burnout and PTSD whether emotional exhaustion caused PTSD or not.

Conclusion

The EMRs had perceived dealing with traumatic events and serious accidents as the most severe acute stressors. There were statistically significant differences between EMRs group and comparative groups as regards most of chronic work-related stressors except for lack of social support with colleagues and supervisors. The EMRs groups had higher levels of physical strain, rapid pace of work, lack of decision control, and organizational decision control. EMRs had higher mean levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization compared with comparative group. In addition, EMRs had more than 10th with clinical levels of PTSD compared with 3% in comparative group. Emotional exhaustion was significantly found among EMRs with PTSD compared with healthy ones. However, there was no evident difference between the two groups as regard depression score. Based on the above results, those emergency responders are in urgent need for stress management and debriefing programs for prevention and alleviating these psychosocial health hazards with particular stress on organizational role in enhancing levels of satisfaction among emergency responders.

Acknowledgement

We wish to express our deep thanks and gratitude to all EMRs at Mansoura city for their help and support during accomplishment of this work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bennett P, Williams Y, Page N, Hood K, Woollard M. Levels of mental health problems among UK emergency ambulance workers. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:235–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.005645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regehr C, Hill J, Goldberg G, Hughes J. Post-mortem inquiries and trauma responses in paramedics and fire fighters. J Interpers Viol. 2003;18:607–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond) 1999;49:225–9. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.4.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Ploeg VE, Kleber RJ. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: Predictors of health symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:40–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Smith GS, Levick NR. Occupational fatalities in emergency medical services: A hidden crisis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:625–32. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.128681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet. 2002;359:2089–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslach C, Jackson SE. “The measurement of experienced burnout”. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geneva: ILO; 1995. International Occupational Safety and Health Information Centre (CIS). International Safety Datasheets on Occupations. Steering Committee meeting, 9-10 March. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Veldhoven M, Meijman TF, Broersen JP, de Zwart BC, van Dijk FJ. Amsterdam: 1997. Manual VBBA: Oonder Search for the perception of psychosocial work load and stress using the questionnaire experience and evaluation of work [Manual of the QEAW: Research on the evaluation of psychosocial work strain and job stress using the Questionnaire on the Experience and Assessment of Work] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Last accessed on July 2012]. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Available from: http://www.mindgarden.com/products/mbi.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck A, Steer RA, Brown GK. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arab Corporation for Psychological Tests. Arabic version of Davidson PTSD Scale according to DSM-IV. 2010. Available from: http://arabtesting.com/ : Personal communication with Dr. Abdel-Mawggod Abdel samiee head manager of Arab corporation for psychological test.

- 13.Reichard AA, Jackson LL. Occupational injuries among emergency responders. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:1–11. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudreaux E, Mandry C. The effects of stressors on emergency medical technicians (Part II): A critical review of the literature and a call for further research. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1996;11:302–7. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0004317x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterud T, Ekeberg O, Hem E. Health status in the ambulance services: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahony KL. Management and the creation of occupational stressors in an Australian and a UK ambulance service. Aust Health Rev. 2001;24:135–45. doi: 10.1071/ah010135a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterud T, Hem E, Ekeberg O, Lau B. Occupational stressors and its organizational and individual correlates: A nationwide study of Norwegian ambulance personnel. BMC Emerg Med. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson S, Cooper C, Cartwright S, Donald I, Taylor P, Millet C. The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J Manag Psych. 2005;20:178–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada N, Ishii N, Nakata M, Nakayama S. Occupational stress among Japanese emergency medical technicians: Hyogo prefecture. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2005;20:115–21. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00002296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank JR, Ovens H. Shift work and emergency medical practice. CJEM. 2002;4:421–8. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500007934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander DA, Klein S. Ambulance personnel and critical incidents: Impact of accident and emergency work on mental health and emotional well-being. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:76–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss SJ, Silady MF, Roes B. Effect of individual and work characteristics of EMTs on vital sign changes during shift-work. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:640–4. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regehr C, Goldberg G, Glancy GD, Knott T. Post-traumatic symptoms and disability in paramedics. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:953–8. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson J. Psychological impact of body recovery duties. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:628–9. doi: 10.1177/014107689308601105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clohessy S, Ehlers A. PTSD symptoms, response to intrusive memories and coping in ambulance service workers. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999;38:251–65. doi: 10.1348/014466599162836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson A, Segesten K. Daily stress and concept of self in Swedish ambulance personnel. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:226–34. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regehr C, Goldberg G, Hughes J. Exposure to human tragedy, empathy, and trauma in ambulance paramedics. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:505–13. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]