Abstract

Risk for developing cancer rises substantially as a result of poorly regulated inflammatory responses to pathogenic bacterial infections. Anti-inflammatory CD4+ regulatory cells (TREG) function to restore immune homeostasis during chronic inflammatory disorders. It seems logical that TREG cells would function to reduce risk of inflammation-associated cancer in the bowel by down-regulating inflammation. It is widely believed, however, that TREG function in cancer mainly to suppress protective anticancer inflammatory responses. Thus roles for inflammation, TREG cells, and gut bacteria in cancer are paradoxical and are the subject of controversy. Our accumulated data build upon the “hygiene hypothesis” model in which gastrointestinal (GI) infections lead to changes in TREG that reduce inflammation-associated diseases. Ability of TREG to inhibit or suppress cancer depends upon gut bacteria and IL-10, which serve to maintain immune balance and a protective anti-inflammatory TREG phenotype. However, under poorly regulated pro-inflammatory conditions, TREG fail to inhibit and may instead contribute to a T helper (Th)-17-driven procarcinogenic process, a cancer state that is reversible by down-regulation of inflammation and interleukin (IL)-6. Consequently, hygienic individuals with a weakened IL-10– and TREG–mediated inhibitory loop are highly susceptible to the carcinogenic consequences of elevated inflammation and show more frequent inflammation-associated cancers. Taken together, these data help explain the paradox of inflammation and TREG in cancer and indicate that targeted stimulation of TREG may promote health and significantly reduce risk of cancer.

Keywords: gut bacteria, inflammation, TREG cells, colon cancer

Introduction

It has become clear that the risk for developing cancer rises substantially as a result of poorly regulated chronic inflammatory responses. Increasing medical and scientific data point to a balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory immune events within the body that dictate outcomes of human health and disease (Powrie and Maloy 2003). An excellent overview by Powrie and Maloy (2003) published in the journal Science describes cells and factors that modulate immune homeostasis. In this context, anti-inflammatory CD4+CD45RBl°CD25+ regulatory T cells (TREG) offer protection from destructive systemic immune events in both humans and mice. We postulate that risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) is greatest when interrelated activities of TREG cells, intestinal bacteria, and innate immunity are unable to restore and support systemic homeostasis.

A functional link between chronic inflammation and cancer has long been suspected, but the crucial molecular pathways that permit communication between cancer cells and inflammatory cell infiltrates largely remain unknown (Coussens and Werb 2002). Evidence for key roles of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 in carcinogenesis are summarized by Balkwill and Coussens in Nature (2004). Data from several inflammation-associated cancer models implicate TNF-α, IL-6, and nuclear factor (NF)-κB as central players bridging inflammation and tumorigenesis as presented by Karin in Nature (2006). Interleukin-6 is also pivotal in carcinogenesis and is associated with gender disparity in cancer (Bromberg and Wang 2009; Naugler et al. 2007). In humans, men are up to 70% more likely than women to suffer from colon cancer and dysregulated IL-6 (J. Lin et al. 2007; Burch et al. 1975). Interleukin-6 may function through activation of Stat3 phosphorylation in tumor cells, resulting in inhibition of dendritic cell maturation (Berishaj et al. 2007; Menetrier-Caux et al. 1998). Interleukin-6 can also have direct effects on tumor cells, leading to increased cell migration (Badache and Hynes 2001) and loss of apoptosis (Badache and Hynes 2001; M. T. Lin et al. 2001). An important pathogenic role for IL-6 has also emerged in social stress, bereavement, cachexia, and aging in humans and in animal models (Galtgalvis et al. 2008; Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2003; Meagher et al. 2007; Pace et al. 2006). Recent studies by Kuchroo and coworkers (Bettelli et al. 2006; Bettelli et al. 2007) involving autoimmunity show that ability of TREG to inhibit or suppress inflammation depends up levels of TNF-α and IL-6. In this paradigm, elevated levels of IL-6 trigger a shift towards T helper–type (Th)-17 host response, rather than an anti-inflammatory TREG phenotype, that further contributes to pathology.

Specific events that trigger carcinogenic inflammatory processes are unknown. In the gastrointestinal tract, bacterial infections are associated with carcinogenic inflammatory host responses in humans (Fox and Wang 2007) and mice (Erdman et al. 2003). Helicobacter pylori bacteria, for example, is classified as a carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Correa 2003; Fox and Wang 2007) and has been convincingly linked with stomach cancer in people (El-Omar and Malfertheiner 2001; Ley and Parsonnet 2000; Parsonnet et al. 1991; Peek and Blaser 2002; Williams and Pounder 1999). A related organism, Helicobacter hepaticus (Ward et al. 1994; Ward et al. 1996), induces CRC in mice (Erdman, Poutahidis et al. 2003). Interestingly, extra-intestinal tumors also arise in mammary gland and other tissues after infection with H. hepaticus (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain et al. 2006) and may be explained by an immune imbalance favoring TNF-α– and IL-6–mediated systemic inflammatory events (Rao et al. 2007). It would follow logically that measures aimed at decreasing inflammation would be beneficial for cancer. Indeed, systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use has been linked with a significant decrease in both sporadic and familial colon cancers in humans (Labayle et al. 1991; Marnett and DuBois 2002; Waddell et al. 1983).

The Hygiene Hupothesis Model and Inflammation

Paradoxically, risk of developing inflammation-associated cancer, such as CRC, is increased in societies with rigorous hygiene practices (Fox et al. 2000), even though individuals have less exposure to bacterial pathogens. Although these improvements in cleanliness have had a dramatic effect on suppressing the incidence of many serious gastrointestinal (GI) infections, with increased hygiene there has also been a concomitant increase in the incidence of several other life-threatening ailments including allergies, autoimmune diseases, and some types of cancer (Belkaid and Rouse 2005; Fox et al. 2000; Weiss 2002). The “hygiene hypothesis” suggests possible beneficial effects of infections in prevention of diseases. This hypothesis is supported by observations that early childhood infections are associated with reduced frequency of aberrant immune reactions such as allergies and asthma later in life (Weiss 2002). The observation that childhood infections suppress diseases associated with inflammation raises the possibility that these same infections may also protect against inflammation-associated cancers.

Prior work in our laboratory (Poutahidis et al. 2007; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2007) and others (Kullberg et al. 2002; Mazmanian et al. 2008) has provided support for a model in which earlier enteric infections suppress inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and cancer by modulating TREG responses, consistent with the observations of Belkaid and Rouse (2005). Specifically, we showed that the beneficial cancer-suppressing effects of microbial infections are dependent on IL-10 (Erdman et al. 2005; Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003; Poutahidis et al. 2007; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006), a cytokine that also provides suppressive and feedback inhibitory effects on allergy and autoimmune responses (Wills-Karp et al. 2001). Early life exposures to microbial products impart benefit of protection from allergies and asthma in people. Although the hygiene hypothesis has been considered in depth for etiology of allergy and auto-immune diseases, few studies other than our own (Poutahidis et al. 2007; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2007) have addressed these concepts as they may relate to inflammation-associated cancers in the colon or in extraintestinal sites.

Our perspective that TREG cells may be beneficial in cancer is soundly reasoned and well supported by research data, but challenges the existing paradigm for TREG cells in cancer.

Taken together, observations in our labs and others link the immune system, GI infections, and seemingly divergent downstream phenotypes: allergies, autoimmune disease, and cancer. Our perspective of a possible beneficial role for anti-inflammatory TREG in cancer contrasts with the widely held belief that TREG function mainly to suppress protective anticancer inflammatory responses (Colombo et al. 2007; Curiel 2008; Curiel et al. 2004). Exploring this concept in which childhood infections protect from inflammatory diseases later in life, we have tested TREG biology in different mouse models to help explain unanswered questions about inflammation and cancer risk.

Mouse Models of CRC

Colorectal cancer is ranked second among the deadliest cancers in this country (American Cancer Society [ACS] 2004; Crawford 1999). Murine models mimicking human disease are attractive for cancer research because of their small size and short mammalian lifespan, well-established characterization, and the availability of genetically modified animals (Kobaek-Larsen et al. 2000). Many studies in mice link chronic bacterial infection with cancer in the lower bowel (Engle et al. 2002; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003; Kado et al. 2001). We have developed a novel model of colitis-associated CRC (Erdman et al. 2001; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003) using 129Sv/Ev mice with targeted disruption of the recombinase-activating gene-2 (Rag2−/−). Rag2−/− mice lack functional lymphocytes (Shinkai et al. 1992) and provide a reproducible model to dissect inflammatory events within innate immunity or to test roles for select subsets of adaptive immune cells (see Table 1) (Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Maloy et al. 2003). Helicobacter hepaticus, a common enteric bacterium of mice (Ward et al. 1994) rapidly triggers IBD and associated CRC in Rag2-deficient mice. Matched 129 wild-type (wt) mice, however, do not develop bowel pathology after H. hepaticus infection. This finding indicates that gut bacteria–triggered innate immune inflammatory responses are sufficient for cancer (see Figure 1), and that cells of adaptive immunity, when working properly, serve to inhibit cancer development and growth (Figure 1E). Lesions in this mouse model resemble CRC in human patients with IBD according to the criteria established by the recent “Pathology of Mouse Models of Intestinal Cancer: Consensus Report” (Boivin et al. 2003).

Table 1.

Mouse models of colorectal cancer (CRC) in humans.

| Murine models of IBD-CRC | ||

|---|---|---|

| 129 wt + Hh | → | no significant pathology (nsp) |

| 129 Rag2−/− | → | nsp |

| Pro-inflammatory | ||

| Rag2−/− + Hh | → | IBD& adeno-CA |

| Rag2−/− + Hh + wt TEFF cells | → | ↑IBD & ↑adeno-CA |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||

| Rag2 + Hh + anti-TNFα | → | nsp |

| Rag2 + Hh + wt TREG cells | → | nsp |

| Rag2 + Hh + IL10-lg fusion protein | → | nsp |

| Murine models of polyp-CRC | ||

|---|---|---|

| B6 wt | → | no significant pathology |

| B6 Min | → | Intestinal adenomatous polyps |

| Pro-inflammatory | ||

| Min + Hh | → | adeno-CA |

| Mn + wi TEFf cells | → | ↑adeno-CA |

| Min + anti-CD25 | → | ↑adeno-CA |

| B6 Rag2−/−Min | → | ↑adeno-CA |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||

| Min + anti-TNFα | → | Few polyps |

| Min + wt TREG cells | → | Few poiyps |

Uncontrolled inflammatory immune events increase the risk of developing cancer. Rag2-deficient mice lack lymphocytes that regulate inflammation (TREG) and as a result are highly susceptible to bacteria-triggered colitis and cancer. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are needed to sustain colonic carcinoma growth in mice, whether or not overt inflammatory disease is evident in cancer. Rao et al. (2006) showed that neutralization of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is sufficient to induce intestinal tumor remission in ApcMin/+ mice, at least in part by restoring homeostasis among CD4+ lymphocytes (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Adoptive transfer of syngeneic IL-10-competent TREG also rapidly restored normal bowel in ApcMin/+ mice; TREG potency to suppress tumors is increased by prior exposures to gut bacteria. These accumulated data point to novel therapeutic approaches for colon cancer in humans.

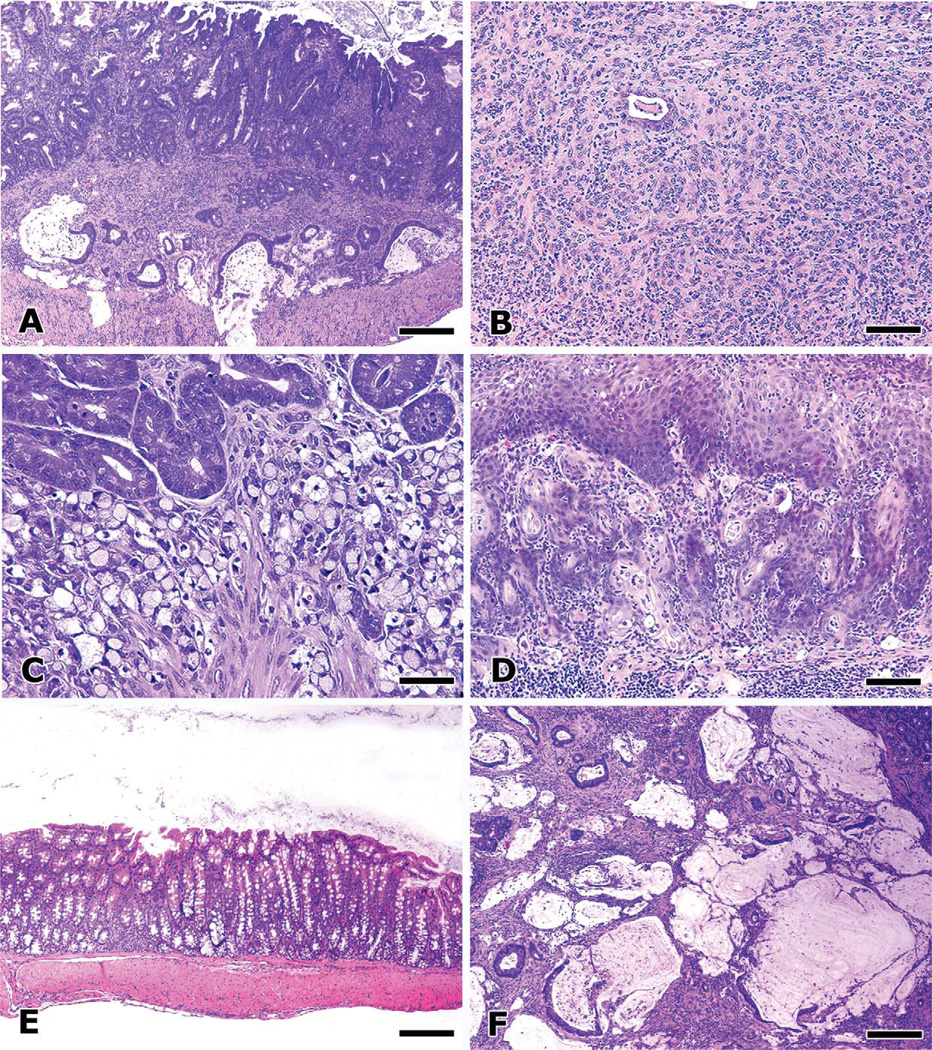

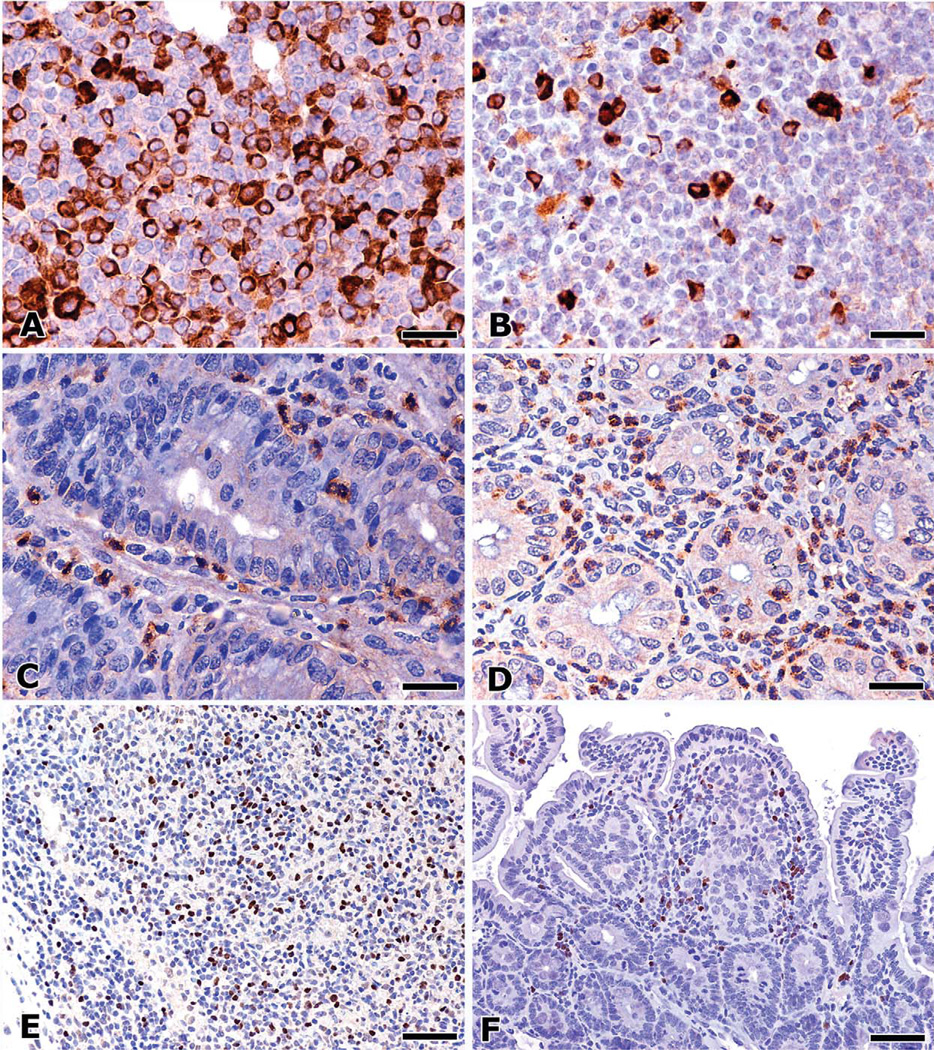

Figure 1.

Inflammation modulates colon cancer progression in mice. Innate immune inflammatory response is sufficient for development of bacteria-triggered CRC in Rag2-deficient mice that entirely lack functional lymphocytes. Intramucosal carcinoma and invasion of isolated glands within the submucosa or muscle layers are readily observed in the colon of Rag2−/− mice two to three months after infection with pathogenic H. hepaticus. Mucinous carcinoma with transmural invasion is a uniform feature after six to eight months postinfection (A) and is the dominant histological type of CRC found in this model. Occasionally, other histological types were encountered, including poorly differentiated intramucosal “medullary” adenocarcinoma (B) and signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (C). Adoptive transfer with pro-inflammatory effector T (TEFF) cells into H. hepaticus–infected mice increased the frequency and diversity of CRC, including adenosquamous carcinoma arising from the anus (D) and extending into the transverse colon. In contrast, anti-inflammatory therapy disrupted the carcinogenic network and even abolished established neoplastic invasion. Normal colon mucosa (E) results after adoptive transfer of anti-inflammatory regulatory T (TREG) cells. Treatment of mice with anti-TNF-α or supplementation with IL-10-Ig fusion protein had similar therapeutic effects. TREG cells require anti-inflammatory IL-10 to prevent pathology, as TREG cells derived from IL-10–deficient donor mice instead greatly exacerbate frequency and the severity of mucinous CRC lesions (F), and peritoneal invasion was a consistent feature. Features of malignancy and neoplastic invasion were associated with increased local and systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17. Hematoxylin and eosin. Bars: A, E, and F, 250 µm; B and D, 100 µm; C, 50 µm.

Host inability to properly regulate inflammation and wound healing leads to cancer. During normal wound healing, CD4+ lymphocytes accelerate innate immune pro-inflammatory responses to eliminate pathogenic organisms, and then afterwards CD4+ TREG down-regulate inflammation to minimize tissue destruction.

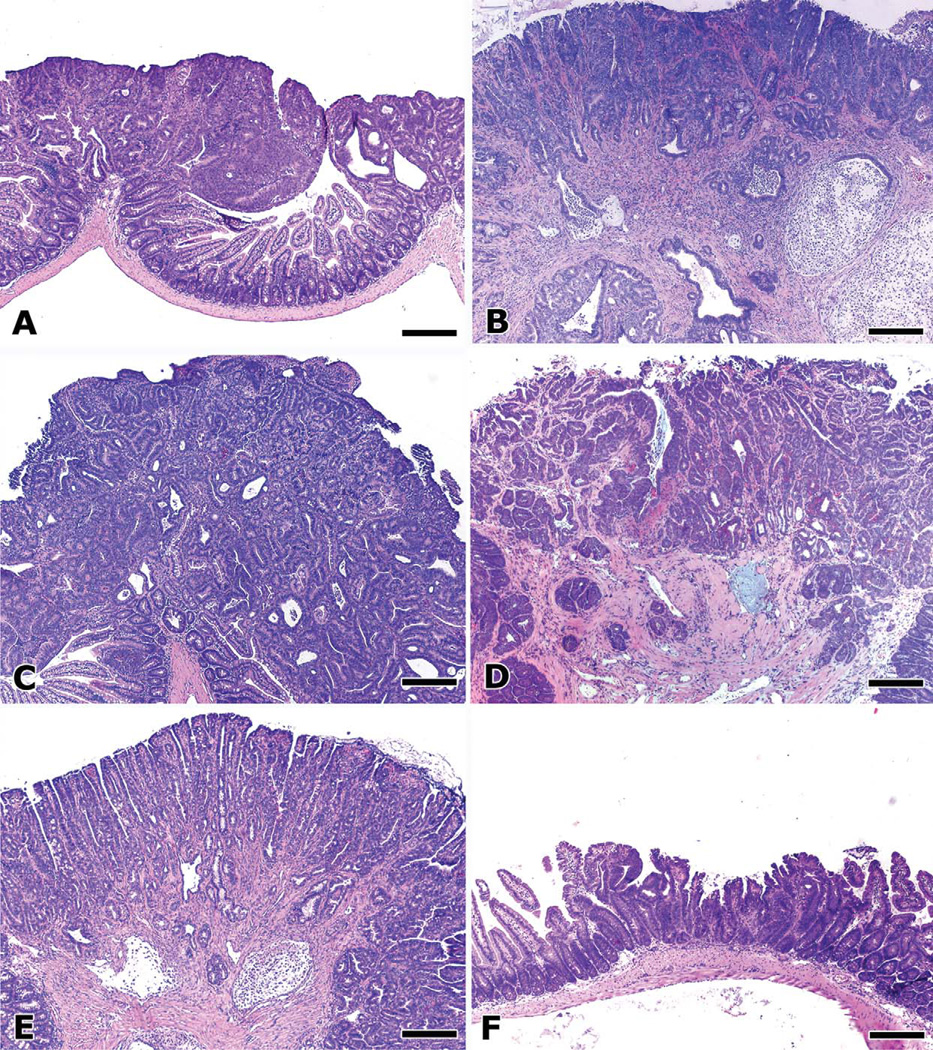

In most human patients, however, CRC is not directly linked with IBD and is more sporadic in nature. Sporadic CRC arises from intestinal adenomatous polyps that undergo a well-characterized series of genetic mutations (Fearon and Vogelstein 1990), rather than from IBD-associated premalignant foci (Riddell et al. 1983). Inactivation of the Apc tumor suppressor gene is an early event in this gene mutation sequence that leads to adenoma growth and dysplasia (Fearon and Vogelstein 1990; Powell et al. 1992). These preneoplastic events have been widely studied in mice with a mutated Apc gene (ApcMin/+ or Min) that rapidly develop intestinal polyposis (Moser et al. 1990). Bowel pathology associated with the ApcMin/+ model is displayed in Figure 2. Although many environmental factors such as diet and steroidal hormones clearly contribute to colon cancer (Crawford 1999), underlying inflammatory factors are also proved to be important in progression of sporadic CRC.

Figure 2.

Systemic inflammatory status determines the outcome of intestinal polyposis in ApcMin/+ mice. Intestinal adenomatous polyp lesions in ApcMin/+ mice (A) typically do not progress to invasive adenocarcinoma. However, experimental manipulations that trigger a host inflammatory response rapidly induce mucinous carcinoma, as with (B) adoptive transfer of pro-inflammatory effector T (TEFF) cells, or with (C) infection with pathogenic H. hepaticus. Features of malignancy and neoplastic invasion were associated with increased local and systemic levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17. Multiplicity of polyps and intramucosal neoplasia and early neoplastic invasion were also increased by (D) depletion of CD25+ cells. Rag2−/−ApcMin/+ mice, which completely lack lymphocytes, are at greater risk for malignant transformation of adenomas into invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (E). Surprisingly, features of malignancy were increased in these mice, commensurate with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, even in the absence of overt inflammatory disease. The same anti-inflammatory treatments that rescued Rag2-deficient mice with colitis-associated CRC also lead to regression of adenomas and CRC in ApcMin/+ mice. Morphology of a minute polyp (F) not only is representative of adenoma regression seen in Rag2-deficient ApcMin/+ mice after treatment with regulatory T cells (TREG), but it also typifies the effect of other anti-inflammatory treatments such as systemic neutralization of TNF-α or supplementation with IL-10-Ig fusion protein. Hematoxylin and eosin. Bars, 250 µm.

Cancer Growth Requires Sustained Host Inflammatory Responses

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are needed to sustain intestinal adenomatous polyps in the ApcMin/+ mice, even though overt colitis is not a typical feature of polyps in mice or in humans.

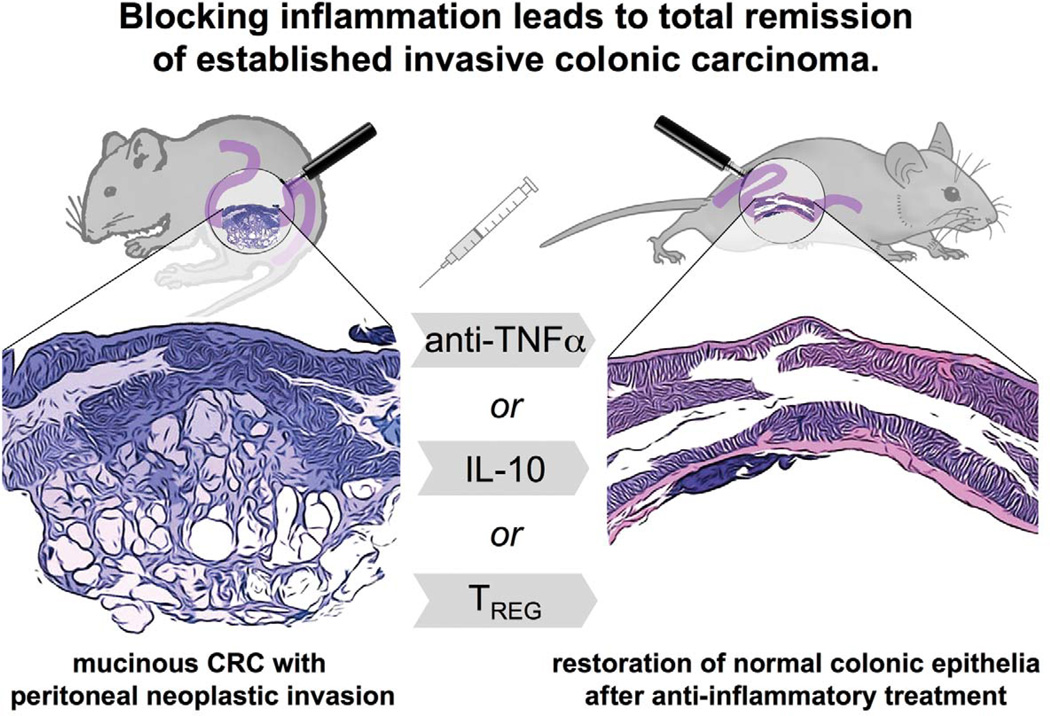

Anti-inflammatory NSAID usage has been linked with a significant decrease in both sporadic and familial colon cancers in humans (Labayle et al. 1991; Marnett and DuBois 2002; Waddell et al. 1983). Studies using Rag2-deficient mice lacking lymphocytes have determined that cancer arises from intestinal bacteria–triggered innate immune events requiring pro-inflammatory cytokines (Erdman, Rao, Poutahidis et al. 2009; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Poutahidis et al. 2007; Poutahidis, et al. 2009; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain et al. 2006). It is now widely recognized that inflammation is required for cancer progression in many tissues such as colon and liver in humans and in mice (Balkwill and Coussens 2004; Balkwill, Charles, and Mantovani 2005; Balkwill and Mantovani 2001). A requirement for inflammation was explicitly shown by Poutahidis et al. (2007) in K-ras–associated carcinoma in mice (Figure 3) whereby systemic administration of anti-TNF-α antibodies or anti-inflammatory IL-10-Ig fusion protein induced complete remission of cancer and abolishedperitoneal neoplastic invasion (Poutahidis et al.2007). Although innate immune inflammatory events are sufficient for cancer in Rag-deficient mice (Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003), we have shown that CD4+ cells clearly contribute to cancer in immunologically intact hosts (Table 1). In these mouse models, chronic inflammation undermines protective functions of TREG cells (Figure 4). Earlier studies by Faubion et al. (2004) in mice revealed that chronic inflammation arising from the bowel may induce thymic involution and TREG suppression, leading to a downward spiral of destructive inflammatory-mediated events that worsen arthritis and IBD (Faubion et al. 2004; Ehrenstein et al, 2004). Restoration of homeostasis through suppression of TNF-α and reinforcement of TREG cells were proposed for human patients suffering from IBD and other uncontrolled inflammatory disorders. These data on IBD lend support to the concept that uncontrolled inflammation weakens the TREG-mediated inhibitory loop and elevates risk for inflammation-associated carcinogenesis.

Figure 3.

Colonic carcinoma depends upon inflammation and is reversible through restoration of immune homeostasis. Our studies in mouse models of intestinal cancer indicate that anti-inflammatory treatments not only prevent cancer from arising, but also abolish established neoplasms. These results suggest that tumor growth and survival may be more dependent upon inflammatory events and more readily reversible than previously thought. The reliance upon inflammatory cells and factors was demonstrated in mouse models of the typical colitis-associated cancer and in mouse models emulating sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC) in humans, as well. Modified from Poutahidis et al. (2007).

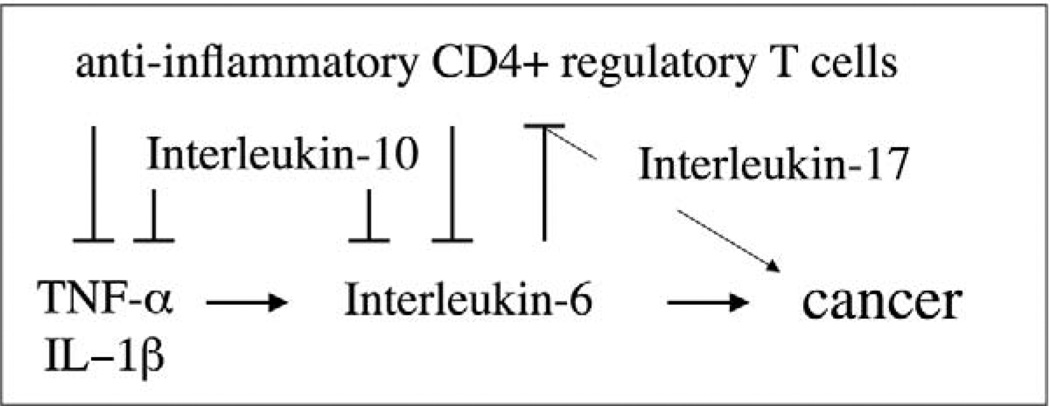

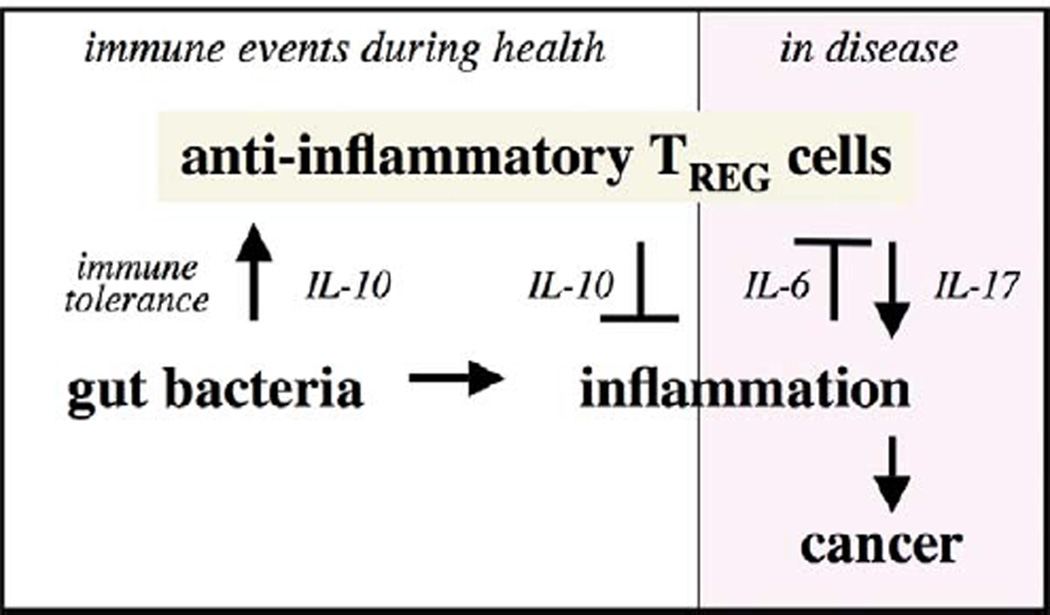

Figure 4.

Proposed immune mechanisms for induction and prevention of cancer. Immune homeostasis is continually reinforced by an IL-10– and TREG-mediated inhibitory loop that allows for protective acute inflammatory responses and then later restores homeostasis. Dysregulation of this host-protective process leads to chronic inflammation involving elevated levels of IL-6 and a Th-17 host response. Individuals with a weakened IL-10– and TREG-mediated inhibitory loop have increased susceptibility to uncontrollable inflammation, IL-6, and IL-17, and are at increased risk for inflammation-associated cancers. Modified from Poutahidis et al. (2007).

In humans, inappropriate inflammatory responses with sustained systemic elevations of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α may lead to many disabling conditions such as arthritis and IBD (Ehrenstein et al. 2004). Highly efficacious anti-inflammatory therapeutic interventions using monoclonal antibodies against TNF (infliximab) and TNF-binding fusion proteins (etanercept) are in widespread use in human patients with IBD and arthritis (Ehrenstein et al. 2004; Pereg and Lishner), albeit with reduced protection from bacterial infections. These antibody treatments demonstrate the requirement for TNF-α in inflammatory disorders in patients (Greten et al. 2004; Lewis and Pollard 2006; Pollard 2004). Humans with elevated TNF-α levels also have poor cancer outcomes (Balkwill et al. 2005; Balkwill and Coussens 2004; Balkwill and Mantovani et al. 2001). Likewise, our neutralization studies using anti-TNF-α anti-bodies in Rag2−/−andin ApcMin/+mice show that inflammation is absolutely required for maintenance of both IBD-associated and polyp-associated intestinal tumors in mice (Erdman, Rao, Poutahidis et al. 2009; Gounaris et al. 2007; Poutahidis et al. 2007; Poutahidis et al. 2009; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Treatment with anti-TNF-α in mice ablates cancer and normalizes expression of cyclooxygenase (Cox)-2, and downstream oncogenes c-myc (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006) and K-ras (Poutahidis et al. 2007) that are linked with cancer in humans.

Roles for TREG Cells and Inflammation on IBD-Associated CRC

Medical and scientific data from humans and mouse models indicate that it is the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory activities within the body that predicts the likelihood of developing diseases (Powrie and Maloy 2003). During pathogenic microbial challenges, a robust pro-inflammatory response mediated by CD4+CD45RBhi (TEFF) cells serves to eliminate pathogenic bacteria. Educated CD4+CD45RBl° TREG cells subsequently down-regulate inflammation and offer protection from destructive immune sequelae. Erdman et al. (2003) showed that IL-10–dependent functions of TREG cells protect from malignancy. Roles for TREG subsets in this process are not completely understood. Interestingly, antigen-specific, IL-10–dependent protection from IBD was enriched for in CD4+CD45RBl° CD25- cells (Kullberg et al. 2002). Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz et al. (2006) found that the greatest protection from cancer resided in both CD25+ and CD25- CD4+CD45RBl° TREG subsets, with the greatest potency arising from combined effects of CD4+ subsets (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Nonetheless, host inability to coordinate IL-10 and TREg to resolve inflammation and restore homeostasis greatly increases the risk for developing cancer.

TREG cells are pivotal in immune homeostasis and overall health due, at least in part, of coordinated activities of cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Powrie and Maloy 2003). A requirement for IL-10 in immune homeostasis has been amply demonstrated in murine models entirely lacking this cytokine that are highly susceptible to bacteria-triggered IBD (Asseman et al. 1999; Kullberg et al. 2002). Deficiency in IL-10 increases susceptibility to inflammation-associated mucinous carcinoma, resembling CRC, which carries a poor prognosis in humans (Boivin et al. 2003). Mice lacking IL-10 are susceptible to IBD-CRC after infection with H. hepaticus; however, their wt counterparts infected with H. hepaticus have only minimal bowel pathology (Erdman, Rao, Poutahidis et al. 2009; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003; Poutahidis et al. 2007). Poutahidis et al. (2007) proposed this difference is a result of interrelated activities of IL-10, TGFβ-1, and IL-6 in disrupted wound healing, an effect that is exacerbated in male mice. As predicted, lack of IL-10 leads to increased susceptibility to chronic inflammation with elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 (Kullberg et al. 2006; Poutahidis et al. 2007). Proposed interrelated roles for these cells and factors are shown in Figure 4.

In colitis-associated CRC, overexpression of IL-17 coincided not only with the site of H. hepaticus infection in the lower bowel, but also within lymph nodes throughout the body (Figure 5A). This finding supported a simplistic model, whereby CD4+ cells insufficient in IL-10 were preferentially recruited to a Th-17 phenotype when faced with a robust pro-inflammatory challenge (Awasthi et al. 2007; Bettelli and Kuchroo 2005; Bettelli et al. 2006; Bettelli, Korn et al. 2007; Bettelli, Oukka et al. 2007; Korn, Reddy et al. 2007; Korn, Oukka et al. 2007), in this case infection with H. hepaticus. This state was readily reversible using exogenous IL-10 (Poutahidis et al. 2007). Bacteria-triggered inflammation in mice mobilized neutrophils bearing TGF-β1 (Figure 5C) and IL-6 (Figure 5D), which may serve to inhibit TREG and promote a Th-17 host response. Depletion studies indicate an important role for innate immune cells such as neutrophils and for mast cells in malignancy (Gounaris et al. 2007; Erdman et al. 2009). Thus, under conditions of insufficient IL-10, there is poor regulation of inflammation and levels of IL-6, which contribute to cancer growth (Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003; Poutahidis et al. 2007). Taken together, these data support that individuals with insufficient IL-10 are more susceptible to uncontrollable inflammation and effects of IL-6 and Th-17, and they may show more frequent inflammation-associated cancers in response to pro-inflammatory challenges such as pathogenic enteric bacteria later in life.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical detection of critical inflammatory cells and cytokines in mouse models of intestinal cancer. The mesenteric lymph nodes of H. hepaticus–infected, IL-10–deficient 129 strain mice show large numbers of IL-17+ cells residing mainly in paracortical and medullary areas. IL-17+ cells are histomorphologically consistent with macrophages and lymphocytes (A). Adoptive transfer of IL-10−/− regulatory T cells into H. hepaticus–infected, Rag2-deficient mice rapidly promotes CRC with peritoneal invasion and simultaneously increases significantly the numbers of IL-17+ cells in lymph nodes (B). Neutrophils are found to be major sources of both TGF-β1(C) and IL-6 (D) within the colonic mucosa. Under these pro-inflammatory conditions, Foxp3+ cells are numerous in the mesenteric lymph nodes (E). Intratumoral Foxp3+ cells within adenomatous polyps of ApcMin/+ mice were numerous within regressing polyps after anti-TNFα–treated ApcMin/+ mice (F). 3,3-diaminobenzidine, hematoxylin counterstain. Bars: A–D, 50 µm; E–G, 25 µm.

Gut Bacterial Infections Trigger Protective IL-10–Dependent TREG Cells

To test directly whether infections earlier in life, such as childhood bacterial exposures in humans, may protect from immune-mediated diseases later in life, we have used a TREg cell titration as in Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain (2006). We found that potency to protect from IBD-associated CRC was increased when TREg cells came from wt donor mice that were previously exposed to H. hepaticus bacteria. Curiously, the lower dosages (1×105 cells) of TREg cells from uninfected donor mice (e.g., “hygienic” donors) actually had increased neoplastic epithelial invasion, matching what is observed under conditions of insufficient IL-10 in TREg cells. Taken together, these findings led us to postulate that individuals with insufficiently educated TREg, such as those arising under hygienic conditions, are predisposed to sustained inflammatory responses and subsequently have a lowered threshold for carcinogenesis (Erdman et al. 2005; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Erdman, Rao, et al. 2003). Proposed interrelated roles for bacteria, innate immunity, and TREg in health and under preneoplastic conditions are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Proposed carcinogenic and protective roles for gut bacteria in cancer. Chronic pathogenic intestinal bacterial infections trigger a well-established sequence of immune events leading to cancer. However, microbial exposures earlier in life also serve to reinforce IL-10– and TREG-mediated protection from inflammatory disorders, which, in turn, conveys protection from inflammation-associated cancers later in life. Stringent hygiene practices deprive the immune system of routine stimulation by bacterial products and IL-10 needed for efficient immune function. Thus, individuals with a na¨ıve immune system and weakened IL-10– and TREG-mediated inhibitory loop have increased susceptibility to uncontrolled inflammation and are at increased risk for inflammation-associated cancers. Insufficient early life microbial exposures in societies with stringent hygiene practices may serve to undermine protective immunity and lower the threshold for future carcinogenic events. Modified from Rao et al. (2007).

Roles for TREG Cells and Inflammation in Sporadic or Familial CRC

To test whether roles for TREg cells in sporadic or familial CRC also conform to the paradigm of IL-6 and IL-17 as in autoimmunity, we have examined C57BL/6 mice heterozygous for a mutation in the Apc gene (ApcMin/+). ApcMin/+ mice are genetically at risk for intestinal polyps and mimic early stages of sporadic CRC in humans (Moser et al. 1990; Powell et al. 1992). Although polyp-CRC is less clearly associated with overt inflammation than IBD-CRC, ApcMin/+ mice have higher systemic and intestinal levels of cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 than matched wt mice, indicative of subclinical inflammatory disease. Importantly, these data match findings of elevated inflammatory cytokine levels in human patients with colon cancer (Bromberg and Wang 2009).

An important role for pro-inflammatory lymphocytes in cancer was demonstrated by Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al., (2006), using adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhi (TEFF) cells, a cell-transfer paradigm otherwise used in mice to emulate autoimmunity in humans (Powrie and Maloy 2003). Cell transfer of TEFF increased tumor multiplicity and features of neoplastic invasion (Table 1), coincident with elevated expression levels of TNF-a, IL-6 and IL-17, but failed to induce IBD in ApcMin/+ mice (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Interestingly, female ApcMin/+ recipients of pro-inflammatory TEFF were at increased risk for mammary carcinoma (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Taken together with the finding that pathogenic gut bacterial infections may trigger carcinogenesis in distant sites such as mammary tissue in mice (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006), these data support the concept that health and disease throughout the body is subject to immune events arising in mucosal surfaces of the bowel.

Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain et al. (2006) used the TREG cell titration assay to test whether prior GI bacterial infections protect ApcMin/+ mice from intestinal polyps. TREG cells from H. hepaticus–infected donors consistently provided complete protection from cancer and more effectively suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 levels in tumor-prone tissues when compared with TREG from uninfected “hygienic” donor mice. These studies showed that protection from cancer is attributable to functions of TREG cells and is more dependent upon the prior conditions of the TREG rather than that of the recipient animals. In some cases, gut bacteria–imbued TREG protection from cancer was more significant in distant sites such as mammae in mice (Rao et al. 2007; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006). Amazingly, prior gut bacterial exposures also significantly enhanced ability of TREG to increase life expectancy in ApcMin/+ mice (Erdman, Rao, Olipitz et al., 2009). These findings raised the possibility that constructive functions of TREG may be applied therapeutically in a wide variety of chronic inflammatory disorders to improve overall health.

Foxp3+ Cell Localization in Cancer

Foxp3 is a widely accepted marker of TREG cells (Bettelli et al. 2006). We have found that under chronic inflammatory conditions, Foxp3+ TREG are increased in circulation and accumulate in large numbers in lymph nodes and surrounding tumors (Figure 5E). However, we have found that tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+ cells are seen primarily during regression of the tumors, as after treatment with anti-TNF-α antibody (Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006) (Figure 5F). In human CRC patients, intratumoral Foxp3+ cells were recently correlated with a favorable clinical outcome (Salama et al. 2009). One intriguing possibility is that TREG not only have diminished efficacy during inflammation but also differentiate directly into IL-17–producing cells (Koenen et al. 2008; Radhakrishnan et al. 2008) in the inflammatory milieu surrounding the growing tumor. In our hands, anti-inflammatory treatments such as anti-TNF-α or exogenous IL-10 led to significantly decreased counts of Foxp36+ cells in the periphery and increased Foxp3+ cells within the tumor parenchyma, commensurate with tumor regression.

Summary and Conclusions

It has been well established in humans and in mice that chronic bacteria-triggered inflammation increases the risk of colonic cancer (Bromberg and Wang 2009; Erdman, Rao, Poutahidis et al. 2009; Erdman, Poutahidis, et al. 2003; Gounaris et al. 2007; Poutahidis et al. 2007; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Boussahmain, et al. 2006; Poutahidis et al. 2009; Rao, Poutahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. 2006). Paradoxically, the risk of humans developing CRC is lower in countries that have less stringent hygiene practices with early life exposures to numerous pathogenic bacteria (ACS 2004; Fox et al. 2000). Accumulated data from our lab and others help explain this enigma. Microbial exposures early in life serve to reinforce the immune system through an IL-10– and TREG-mediated feedback loop, which, in turn, conveys protection from inflammatory challenges later in life and reduces the risk of inflammation-associated cancers. Sporadic intestinal cancers arising from adenomatous polyps fit this inflammatory bowel paradigm, even in the absence of overt IBD. TREG cells appear to restore intestinal homeostasis through immune tolerance to intestinal bacteria, as proposed by Kullberg et al. (2002), Powrie and Maloy (2003), and Mazmanian and coworkers (Chow and Mazmanian 2009; Mazmanian et al. 2008). Dysregulation of this protective process leads to chronic inflammation with elevated levels of IL-6, impaired TREG, and a Th-17 host response, as described by Bettelli and coworkers (Bettelli et al. 2006; Bettelli, Oukka, and Kuchroo 2007). Extrapolating these results to humans, individuals with a naı¨ve immune system and weakened IL-10– and TREG-mediated inhibitory loop would be more susceptible to uncontrollable elevations in inflammation and IL-6 and IL-17, and they would show more frequent inflammation-associated cancers in response to pro-inflammatory challenges later in life.

Taken together, these data help explain interrelated roles of gut bacteria, inflammation, and TREG cells. Although it is widely believed that TREG interfere with constructive antitumor host responses (Colombo et al. 2007; Curiel et al. 2004), our data show that TREG function in cancer similarly to other inflammatory disorders involving TNF-α, IL-6, and a Th-17 host response. Anti-inflammatory properties of TREG within the bowel clearly serve to routinely inhibit destructive process and promote health throughout the body. Under pro-inflammatory host conditions, however, TREG fail to inhibit inflammation and instead may fuel carcinogenic events by contributing to host pro-inflammatory responses. This outcome is displayed under conditions of insufficient IL-10 or with stringent hygiene practices in youth. Insufficient early life microbial exposures in modern society may serve to undermine protective immunity and lower the threshold for future carcinogenic events. Rao, Pou-tahidis, Ge, Nambiar, Horwitz, et al. (2006) first showed that neutralization of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is sufficient to induce intestinal tumor remission in ApcMin/+ mice. Therapeutic interventions such as infliximab and etanercept are widely used in human patients with inflammatory disorders (Ehrenstein et al. 2004; Pereg and Lishner 2005) and could rapidly be translated into CRC therapy in humans. These emerging data highlight the importance of better understanding TREG biology in cancer to exploit host immunity as a powerful tool in cancer therapy. Targeting the underlying inflammatory causes and reinforcing beneficial systemic roles for TREG may yield enormous benefits to eradicate cancer. Harnessing the power of the immune system may provide more effective and less toxic alternatives to traditional chemotherapy for treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chakib Boussahamian for assistance with histology, Tatiana Levkovich for technical support, and Brian Morrison for help with figures. This work was supported by NIH R01CA108854 (SEE), DOD Contract W81XWH-05-01-0460 (SEE), and Pythagoras II Grant 80860 (TP).

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IL

interleukin

- Rag

recombinase activating gene (lacking functional lymphocytes)

- TEFF

pro-inflammatory CD4+ effector T cell

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TREG

anti-inflammatory CD4+ regulatory T cell

- wt

wild type (genotype)

Footnotes

This material was presented on June 25, 2009 at the Society of Toxicologic Pathology meeting.

References

- American Cancer Society (ACS) Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Cancer Fact and Figures. ACS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:995–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badache A, Hynes NE. Interleukin 6 inhibits proliferation and, in cooperation with an epidermal growth factor receptor autocrine loop, increases migration of T47D breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Coussens LM. Cancer: An inflammatory link. Nature. 2001;431:405–406. doi: 10.1038/431405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltgalvis KA, Berger FG, Pena MM, Davis JM, Muga SJ, Carson JA. Interleukin-6 and cachexia in ApcMin /+ mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R393–R401. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00716.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ni1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berishaj M, Gao SP, Ahmed S, Leslie K, Al-Ahmadie H, Gerald WL, Bornmann W, Bromberg JF. Stat3 is tyrosine-phosphorylated through the interleukin-6/glycoprotein 130/Janus kinase pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R32. doi: 10.1186/bcr1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. IL-12- and IL-23-induced T helper cell subsets: Birds of the same feather flock together. J Exp Med. 2007;201:169–171. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: The third member of the effector T cell trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. T(H)-17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:345–350. doi: 10.1038/ni0407-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow TP, Russell R, Besselsen DG, Godfrey VL, Doetschman T, Dove WF, Pitot HC, Halberg RB, Itzkowitz SH, Groden J, Coffey RJ. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: Consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:762–777. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch JC, Byrd BF, Vaughn WK. The effects of long-term estrogen administration to women following hysterectomy. Front Horm Res. 1975;3:208–214. doi: 10.1159/000398277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow J, Mazmanian SK. Getting the bugs out of the immune system: Do bacterial microbiota “fix” intestinal T cell responses? Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo MP, Piconese S. Regulatory-T-cell inhibition versus depletion: The right choice in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:880–887. doi: 10.1038/nrc2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:238s–241s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 1999;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JM. Robbins Pathological Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. The gastrointestinal tract. [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ. Regulatory T cells and treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, Zhu Y, Wei S, Kryczek I, Daniel B, Gordon A, Myers L, Lackner A, Disis ML, Knutson KL, Chen L, Zou W. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein MR, Evans JG, Singh A, Moore S, Warnes G, Isenberg DA, Mauri C. Compromised function of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and reversal by anti-TNFalpha therapy. J Exp Med. 2004;200:277–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Omar EM, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2001;17 [Google Scholar]

- Engle SJ, Ormsby I, Pawlowski S, Boivin GP, Croft J, Balish E, Doetschman T. Elimination of colon cancer in germ-free transforming growth factor beta 1-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6362–6366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Fox JG, Sheppard BJ, Feldman D, Horwitz BH. Regulatory T cells prevent non-B non-T colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(Suppl 1):A524. [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Poutahidis T, Tomczak M, Rogers AB, Cormier K, Plank B, Horwitz BH, Fox JG. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes inhibit microbially induced colon cancer in Rag2-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:691–702. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Ihrig MM, Ge Z, Feng Y, Tomczak M, Rogers AB, Horwitz BH, Fox JG. CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory lymphocytes require interleukin 10 to interrupt colon carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6042–6050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Rogers AB, Taylor CL, Jackson EA, Ge Z, Lee CW, Schauer DB, Wogan GN, Tannenbaum SR, Fox JG. Nitric oxide and TNF-α trigger colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis in Helicobacter hepaticus-infected, Rag2-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1027–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812347106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman SE, Sohn JJ, Rao VP, Nambiar PR, Ge Z, Fox JG, Schauer DB. CD4+CD25+ regulatory lymphocytes induce regression of intestinal tumors in ApcMin /+ mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3998–4004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faubion WA, De Jong YP, Molina AA, Ji H, Clarke K, Wang B, Mizoguchi E, Simpson SJ, Bhan AK, Terhorst C. Colitis is associated with thymic destruction attenuating CD4+25+ regulatory T cells in the periphery. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1759–1770. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumo-rigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JG, Beck P, Dangler CA, Whary MT, Wang TC, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat Med. 2000;6:536–542. doi: 10.1038/75015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris E, Erdman SE, Restaino C, Gurish MF, Friend DS, Gounari F, Lee DM, Zhang G, Glickman JN, Shin K, Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Weissleder R, McNagny KM, Khazaie K. Mast cells are an essential hematopoietic component for polyp development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19977–19982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado S, Uchida K, Funabashi H, Iwata S, Nagata Y, Ando M, Onoue M, Matsuoka Y, Ohwaki M, Morotomi M. Intestinal microflora are necessary for development of spontaneous adenocarcinoma of the large intestine in T-cell receptor beta chain and p53 double-knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2395–2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobaek-Larsen M, Thorup I, Diederichsen A, Fenger C, Hoitinga MR. Review of colorectal cancer and its metastases in rodent models: Comparative aspects with those in humans. Comp Med. 2000;50:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–2352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo V, Bettelli E. Th17 cells: Effector T cells with inflammatory properties. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Reddy J, Gao W, Bettelli E, Awasthi A, Petersen TR, Backstrom BT, Sobel RA, Wucherpfennig KW, Strom TB, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Myelin-specific regulatory T cells accumulate in the CNS but fail to control autoimmune inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:423–431. doi: 10.1038/nm1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg MC, Jankovic D, Feng CG, Hue S, Gorelick PL, McKenzie BS, Cua DJ, Powrie F, Cheever AW, Maloy KJ, Sher A. IL-23 plays a key role in Helicobacter hepaticus-induced T cell-dependent colitis. J Exp Med. 203:2485–2494. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg MC, Jankovic D, Gorelick PL, Caspar P, Letterio JJ, Cheever AW, Sher A. Bacteria-triggered CD4(+) T regulatory cells suppress Helicobacter hepaticus-induced colitis. J Exp Med. 2002;196:505–515. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labayle D, Fischer D, Vielh P, Drouhin F, Pariente A, Bories C, Duhamel O, Trousset M, Attali P. Sulindac causes regression of rectal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:635–639. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90519-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006;66:605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley C, Parsonnet J. Gastric adenocarcinoma. In: Goedert JJ, editor. Infectious Causes of Cancer. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 389–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Zhang SM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Lee IM. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors, and risk of colorectal cancer among women in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:794–801. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Juan CY, Chang KJ, Chen WJ, Kuo ML. IL-6 inhibits apoptosis and retains oxidative DNA lesions in human gastric cancer AGS cells through up-regulation of anti-apoptotic gene mcl-1. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1947–1953. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloy KJ, Salaun L, Cahill R, Dougan G, Saunders NJ, Powrie F. CD4+CD25+ T(R) cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2003;197:111–119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marnett LJ, DuBois RN. COX-2: A target for colon cancer prevention. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:55–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082301.164620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher MW, Johnson RR, Vichaya EG, Young EE, Lunt S, Welsh CJ. Social conflict exacerbates an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:314–330. doi: 10.1177/1524838007303506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menetrier-Caux C, Montmain G, Dieu MC, Bain C, Favrot MC, Caux C, Blay JY. Inhibition of the differentiation of dendritic cells from CD34(+) progenitors by tumor cells: Role of interleukin-6 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1998;92:4778–4791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, Heim CM. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–1633. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek RM, Jr, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg D, Lishner M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention and treatment of cancer. J Intern Med. 2005;258:115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Haigis KM, Rao VP, Nambiar PR, Taylor CL, Ge Z, Watanabe K, Davidson A, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Rapid reversal of interleukin-6-dependent epithelial invasion in a mouse model of microbially induced colon carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2614–2623. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutahidis T, Rao VP, Olipitz W, Taylor CL, Jackson EA, Levkovich T, Lee CW, Fox JG, Ge Z, Erdman SE. CD4+ lymphocytes modulate prostate cancer progression in mice. Int J Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ijc.24452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, Bryan TM, Hamilton SR, Thibodeau SN, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–237. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Maloy KJ. Immunology. Regulating the regulators. Science. 2003;299:1030–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1082031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan S, Cabrera R, Schenk EL, Nava-Parada P, Bell MP, Van Keulen VP, Marler RJ, Felts SJ, Pease LR. Repro-grammed FoxP3+ T regulatory cells become IL-17+ antigen-specific autoimmune effectors in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:3137–3147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Breast cancer: Should gastrointestinal bacteria be on our radar screen? Cancer Res. 2007;67:847–850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Ge Z, Nambiar PR, Boussahmain C, Wang YY, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Innate immune inflammatory response against enteric bacteria Helicobacter hepaticus induces mammary adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7395–7400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VP, Poutahidis T, Ge Z, Nambiar PR, Horwitz BH, Fox JG, Erdman SE. Pro-inflammatory CD4+ CD45RB(hi) lymphocytes promote mammary and intestinal carcinogenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:57–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, Appelman HD, Fenoglio CM, Haggitt RC, Ahren C, Correa P, Hamilton SR, Morson BC, et al. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: Standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:931–968. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama P, Phillips M, Grieu F, Morris M, Zeps N, Joseph D, Platell C, Iacopetta B. Tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T regulatory cells show strong prognostic significance in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:186–192. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell WR, Gerner RE, Reich MP. Nonsteroid antiinflammatory drugs and tamoxifen for desmoid tumors and carcinoma of the stomach. J Surg Oncol. 1983;22:197–211. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930220314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Anver MR, Haines DC, Benveniste RE. Chronic active hepatitis in mice caused by Helicobacter hepaticus. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:959–968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JM, Anver MR, Haines DC, Melhorn JM, Gorelick P, Yan L, Fox JG. Inflammatory large bowel disease in immuno-deficient mice naturally infected with Helicobacter hepaticus. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss ST. Eat dirt—the hygiene hypothesis and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:930–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MP, Pounder RE. Helicobacter pylori: From the benign to the malignant. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(99)00657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills-Karp M, Santeliz J, Karp CL. The germless theory of allergic disease: Revisiting the hygiene hypothesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:69–75. doi: 10.1038/35095579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]