Cavβ1a acts as a voltage-gated calcium channel-independent regulator of gene expression in muscle progenitor cells and is required for their normal expansion during myogenic development.

Abstract

Voltage-gated calcium channel (Cav) β subunits are auxiliary subunits to Cavs. Recent reports show Cavβ subunits may enter the nucleus and suggest a role in transcriptional regulation, but the physiological relevance of this localization remains unclear. We sought to define the nuclear function of Cavβ in muscle progenitor cells (MPCs). We found that Cavβ1a is expressed in proliferating MPCs, before expression of the calcium conducting subunit Cav1.1, and enters the nucleus. Loss of Cavβ1a expression impaired MPC expansion in vitro and in vivo and caused widespread changes in global gene expression, including up-regulation of myogenin. Additionally, we found that Cavβ1a localizes to the promoter region of a number of genes, preferentially at noncanonical (NC) E-box sites. Cavβ1a binds to a region of the Myog promoter containing an NC E-box, suggesting a mechanism for inhibition of myogenin gene expression. This work indicates that Cavβ1a acts as a Cav-independent regulator of gene expression in MPCs, and is required for their normal expansion during myogenic development.

Introduction

The voltage-gated calcium channel (Cav) β subunit (Cavβ) was initially purified from rabbit skeletal muscle as part of the dihydropyridine receptor (now termed Cav1.1) complex (Curtis and Catterall, 1984). A total of four Cavβ genes have been cloned (Cacnb1–4), each with multiple splice variants (Buraei and Yang, 2010). Cavs contain an ER retention signal that is masked by Cavβ binding, allowing both proteins to traffic to the plasma membrane (Bichet et al., 2000). Cavβ interaction with Cavs also serves to modulate gating properties of the channel (Lacerda et al., 1991; Varadi et al., 1991). Cavβ subunits contain two protein interaction domains: Src homology 3 (SH3) and guanylate kinase (GK), which act both together and individually to regulate channel function (Takahashi et al., 2004, 2005; Miranda-Laferte et al., 2011).

Cavβ1a is the dominant β subunit isoform/splice variant in skeletal muscle, where it associates with Cav1.1 in transverse tubules and plays a critical role in excitation–contraction (EC) coupling, the process of converting an electrical stimulus to mechanical response. Cavβ1a is necessary for proper calcium channel expression in the transverse tubules (Gregg et al., 1996), and also functions to organize Cav1.1 into defined groups of four (tetrads), which pair to a single ryanodine receptor (RyR; Schredelseker et al., 2005, 2009). This strict geometrical organization and 4:1 stoichiometry is necessary for proper EC coupling. The β1-null mouse (Gregg et al., 1996) and the relaxed (redts25) zebrafish (Zhou et al., 2006) both show paralysis due to total lack of EC coupling, underscoring the importance of Cavβ1a in EC coupling. The β1-null mouse (hereafter called Cacnb1−/−) also shows severely reduced skeletal muscle mass at birth, attributed to a lack of activity during development.

In the last decade, over a dozen additional, noncalcium channel binding partners have been described in the literature for multiple Cavβ subunit isoforms (Béguin et al., 2001; Hohaus et al., 2002; Hibino et al., 2003; Grueter et al., 2006; Gonzalez-Gutierrez et al., 2007; Hidalgo and Neely, 2007; Kiyonaka et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008; Catalucci et al., 2009; Buraei and Yang, 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Tadmouri et al., 2012). Several additional reports show the nuclear localization of all four Cavβ subunits, either alone (Colecraft et al., 2002; Subramanyam et al., 2009) or when cotransfected with members of the RGK family of proteins (Béguin et al., 2006; Leyris et al., 2009). Two studies have demonstrated transcriptional regulation in vitro by the neuronal Cavβ3 (Zhang et al., 2010) and Cavβ4c subunits (Hibino et al., 2003), and a recent comprehensive work showed that Cavβ4 inhibits tyrosine hydroxylase expression in brain tissue (Tadmouri et al., 2012).

Although the role of Cavβ1a in mature skeletal muscle is well understood, its role in muscle progenitor cells (MPCs), if any, is not known. MPCs are capable of rapid proliferation during development, or after activation in response to muscle damage in adults, after which they can differentiate and fuse together into mature myofibers. Unlike mature myofibers, MPCs are capable of DNA replication and cell division while maintaining a commitment to the skeletal muscle lineage. Regulation of cell fate by myogenic transcription factors such as Pax7, MyoD, and myogenin is well understood; however, questions still remain about how these factors themselves are regulated.

We sought to define the physiological role for Cavβ subunits in the nucleus, specifically in MPCs. Here we report a pathway by which Cavβ1a regulates skeletal muscle mass during embryonic development by suppression of the Myog promoter.

Results

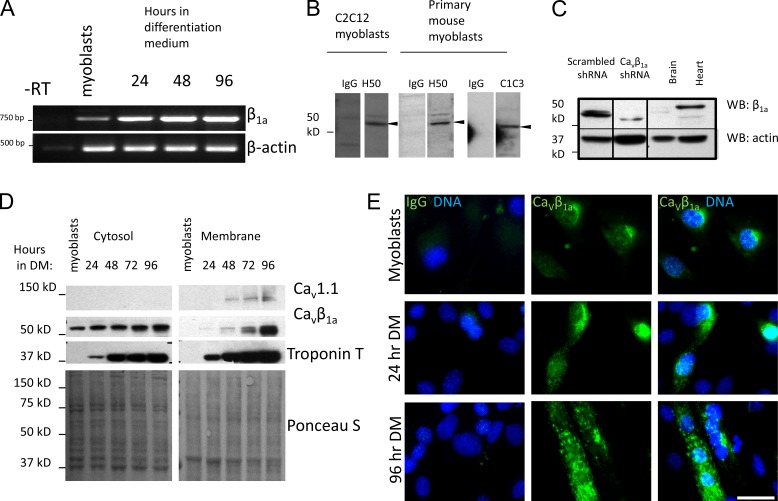

Cavβ1a expression in muscle progenitor cells

Although CaVβ subunits have been studied in myotubes, specifically the muscle-specific splice variant CaVβ1a (coded by the Cacnb1 gene), little is known about their expression in MPCs (myoblasts). A microarray study suggested that while Cacnb1 mRNA expression increases during differentiation, it still expresses in significant quantities in subconfluent, proliferating C2C12 myoblasts (Tomczak et al., 2004). Therefore, we sought to characterize Cacnb1 expression at the mRNA and protein level in C2C12 and primary mouse myoblasts. RT-PCR with primers to the muscle-specific Cacnb1 splice variant A (β1a), which codes for the CaVβ1a protein, detected CaVβ1a mRNA in subconfluent myoblasts, which increased during myogenic differentiation (Fig. 1 A). We next characterized CaVβ1a subunit protein expression in C2C12 and primary myoblasts, using two different CaVβ1a antibodies. A protein band close to the expected molecular weight of CaVβ1a (55 kD) appeared specifically in both C2C12 and primary myoblasts, using both antibodies, compared with isotype IgG controls (Fig. 1 B, CaVβ1a antibody clone H-50 was used for the remainder of experiments). CaVβ1a-specific shRNA-mediated knockdown of this protein band further confirmed its identity as CaVβ1a (Fig. 1 C). Additionally, although the antibody we used did label brain and cardiac protein bands (presumably other CaVβ isoforms), these had different molecular weights (Fig. 1 C). To examine CaVβ1a expression and localization during myogenesis, we analyzed cytosolic and membrane lysates collected from proliferating (subconfluent in growth medium [GM]) and differentiating C2C12 cells (24–96 h in differentiation medium [DM]) by Western blot (Fig. 1 D). In proliferating myoblasts, CaVβ1a appeared in the cytosolic but not plasma membrane fractions, whereas the CaV1.1 protein was absent, as expected (Bidaud et al., 2006). The absence of CaVβ1a in the membrane fraction of myoblasts suggests it does not interact with any channels, CaV1.1 or otherwise, indicating a nonchannel function. Cytosolic CaVβ1a protein expression increased mildly during differentiation, but showed a large increase in the membrane fraction after 48 h in DM, concomitantly with the appearance of CaV1.1, reaffirming the classical role of CaVβ1a as a CaV1.1 binding partner in mature skeletal muscle. Immunostaining of CaVβ1a showed a very faint nuclear and perinuclear signal in proliferating and early-fusing myoblasts. However, in fully differentiated myotubes a strong punctate signal was observed, presumably corresponding to CaVβ1a associated with CaV1.1 at the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 E). These results support the idea that myoblasts do not express CaVs, yet still express CaVβ1a. Thus, in MPCs, CaVβ1a exists in a spatially and temporally separate pool from its constituent CaV, raising the likelihood of CaV-independent functions.

Figure 1.

Cavβ1a expression in MPCs. (A) mRNA expression of Cavβ1a in primary MPCs cultured in GM (myoblasts) and after 24, 48, or 96 h in DM (−RT, nonreverse-transcribed control). (B) Expression of Cavβ1a protein in C2C12 myoblasts and primary MPCs detected by Western blot using antibody clones H-50 and C1C3. A distinct band was detected (arrowheads) with a molecular weight of ∼55 kD. Each lane represents individual strip cut from same membrane. (C) Western blot for Cavβ1a expression in C2C12 stably transfected with scrambled control or Cavβ1a-specific shRNA. Brain and heart protein lysates were also run as negative controls. (D and E) C2C12 myoblasts were grown to confluence in GM, then switched to DM for analysis at 24-h intervals. (D) Western blot for Cavβ1a and Cav1.1 in cytosolic and membrane fractions. Troponin T is a marker of myogenic differentiation and Ponceau S stain shows equal loading. (E) Immunofluorescent staining for endogenous Cavβ1a (green) and DNA (Hoechst stain, blue). Some nuclei are out of focus with visible Cavβ1a staining. Bar, 100 µm.

Nuclear Cavβ1a

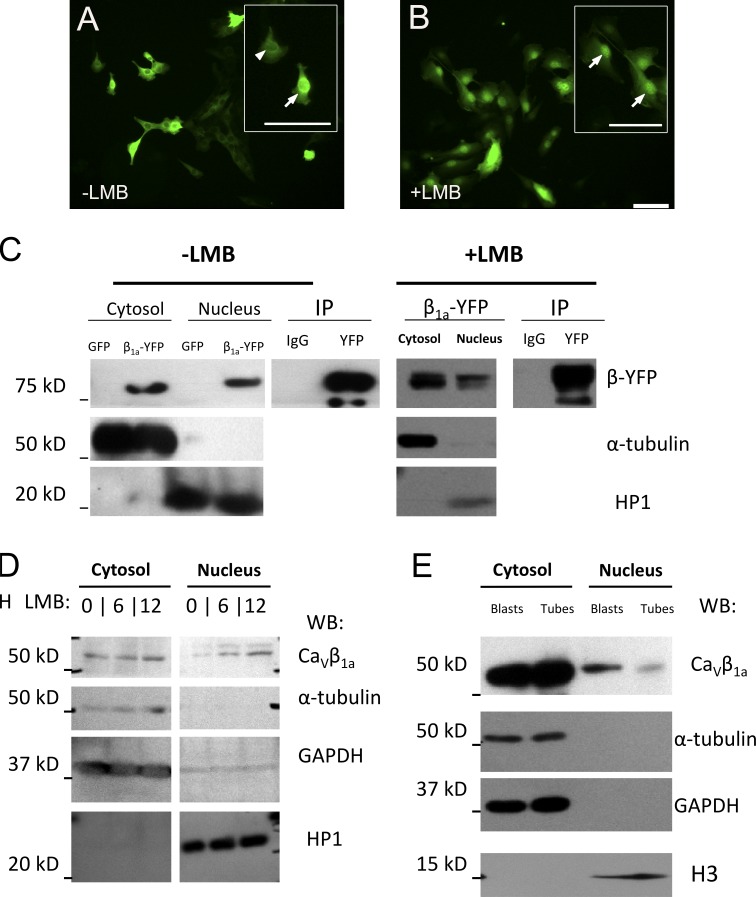

As other CaVβ subunits have been observed in the nucleus of various cell types, we hypothesized CaVβ1a may localize there in MPCs as well. Because our antibodies did not appear sensitive enough for clear immunofluorescent detection in C2C12 myoblasts, we constructed a recombinant adenoviral (RAd) vector to overexpress a Cavβ1a-YFP plasmid (Leuranguer et al., 2006) in these cells. Cavβ1a-YFP shows a predominantly cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 2 A), although some cells also exhibited substantial fluorescence in the nucleus. However, after 3 h of treatment with the CRM1 nuclear export channel blocker leptomycin-B (LMB), all cells exhibited Cavβ1a-YFP fluorescence predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 2 B). Cavβ1a antibody staining of these treated cells overlapped with YFP fluorescence in the nucleus (unpublished data). To further confirm the translocation of Cavβ1a-YFP into the nucleus of C2C12 myoblasts, we obtained pure cytosolic and nuclear fractions from Cavβ1a-YFP–expressing cells, and analyzed Cavβ1a-YFP protein expression by Western blot (Fig. 2 C). Cavβ1a-YFP was clearly present in the nucleus, even without LMB treatment. In both untreated and LMB-treated cells, Cavβ1a-YFP could be immunoprecipitated from nuclear fractions with an YFP antibody, further indicating the specific localization of Cavβ1a-YFP (Fig. 2 C). It is important to note that the expected and observed size of Cavβ1a-YFP is nearly 80 kD (Fig. 2 C), far above the size limit for passive diffusion into the nucleus (<50 kD), suggesting that Cavβ1a-YFP is rapidly and actively transported into the nucleus of C2C12 myoblasts. Furthermore, when examined carefully, the Cavβ1a-YFP band in nuclear fractions appears to be of a slightly higher molecular weight than cytosolic Cavβ1a-YFP, indicating that a possible post-translational modification is required for, or induced by, nuclear translocation.

Figure 2.

Cavβ1a-YFP and endogenous Cavβ1a translocate to the nucleus of myoblasts. (A) C2C12 myoblasts transfected with Cavβ1a-YFP, and (B) after treatment with LMB. Arrowhead indicates cell with predominantly cytoplasmic Cavβ1a-YFP, arrows indicate cells with predominantly nuclear Cavβ1a-YFP. Bars, 100 µm. (C) Detection and immunoprecipitation of Cavβ1a-YFP in the nuclear fraction of untreated and LMB-treated C2C12 myoblasts by Western blot. (D) Western blot for endogenous Cavβ1a in C2C12 myoblasts. Cytosolic and nuclear fractions of C2C12 myoblasts treated with LMB for 0, 6, and 12 h. (E) Comparison of Cavβ1a protein levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions in myoblasts vs. myotubes. Tubulin and GAPDH are cytosolic markers, and HP1 and H3 are nuclear proteins. Figures are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We next wanted to determine if endogenous Cavβ1a protein enters the nucleus of myoblasts. Immunostaining for endogenous Cavβ1a after LMB treatment in nontransfected cells did not detect any clear nuclear enrichment (unpublished data), likely due to a lack of sensitivity or epitope masking. To circumvent these issues, we performed a nuclear fractionation protocol and Western blot analysis, which is more sensitive and avoids epitope masking (Fig. 2 D). Compared with untreated cells, Cavβ1a is enriched in the nuclear fraction of 6- and 12-h LMB-treated C2C12 myoblasts. As Cavβ1a expression levels change in cytoplasmic and membrane fractions with myogenic differentiation, we also examined if Cavβ1a nuclear expression changes during this process (Fig. 2 E). Interestingly, while cytoplasmic Cavβ1a increases modestly with differentiation, nuclear Cavβ1a appears to decline, further underscoring a possible MPC-specific role for Cavβ1a in the nucleus. Close examination reveals that, like Cavβ1a-YFP, endogenous Cavβ1a also seems to exist as a slightly higher molecular weight species (Fig. 2, D and E) within the nucleus, supporting the notion of a post-translational modification. In sum, these data strongly suggest that Cavβ1a enters the nucleus of MPCs through some means of active transport.

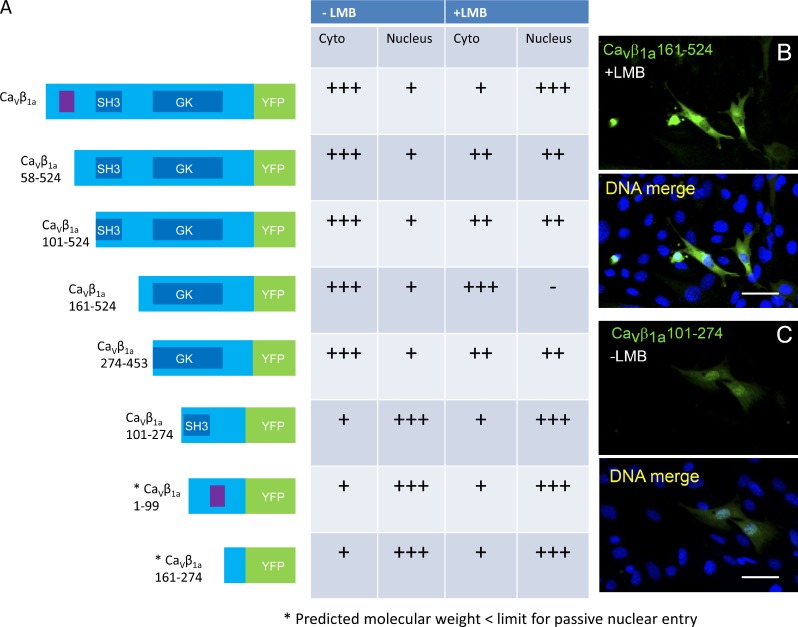

Cavβ1a possesses variable N- and C-terminal domains, as well as conserved SH3, HOOK, and GK domains. We wanted to determine which domain of Cavβ1a endows its ability to enter the nucleus, and also whether this is a specific ability of Cavβ1a, or a mechanism conserved in all Cavβ subunits. All four Cavβ subunit isoforms have been reported to enter the nucleus (Buraei and Yang, 2010), and data suggests that this ability may lie within the SH3 domain (Colecraft et al., 2002; Hibino et al., 2003). However, Cavβ1a also possesses a yeast nuclear localization sequence (NLS), KRKGRFKR (Hicks and Raikhel, 1995). This sequence, located in Cavβ1a’s N-terminal domain, is not highly conserved in other Cavβ subunits, and thus may confer in Cavβ1a a specific ability to enter the nucleus. We created various truncation mutants of the Cavβ1a-YFP protein and tested their individual ability to enter the nucleus in the presence and absence of LMB (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S1). All constructs except for CaVβ1a161-524 (lacking N terminus and SH3 domains; Fig. 3 B) showed enriched nuclear localization after LMB treatment, including the mutant lacking the putative yeast NLS. Several constructs lacking the GK domain showed strong nuclear localization without LMB; however, this could be attributed to low molecular weight. One exception is Cavβ1a-101-274 (Fig. 3 C), which contains SH3 and middle regions, and has a predicted molecular weight (47 kD when fused to YFP) close to the 50-kD barrier. Overall, these data suggest that the nuclear localization domain of Cavβ1a lies somewhere in the SH3 or middle region, in agreement with previous findings for other CaVβ subunits.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the CaVβ1a nuclear localization domain. (A) Diagram of constructed CaVβ1a-YFP truncation mutants and respective cytoplasmic and nuclear intensity in untreated and LMB-treated cells. Conserved SH3 and GK domains are noted in dark blue, putative NLS highlighted in purple, and YFP sequence in green. Construct names indicate amino acids remaining after truncation, with CaVβ1a-1-524 as full-length CaVβ1a. Table reflects relative intensity of cytoplasmic (Cyto) and nuclear Cavβ1a. (B) Enlarged image of CaVβ1a-161-524, which is absent from the nucleus after LMB treatment. (C) Enlarged image of CaVβ1a-101-274, which is present in the nucleus without LMB treatment. Nuclei (DNA) in all images were stained blue with Hoechst dye. Bars: (B and C) 50 µm.

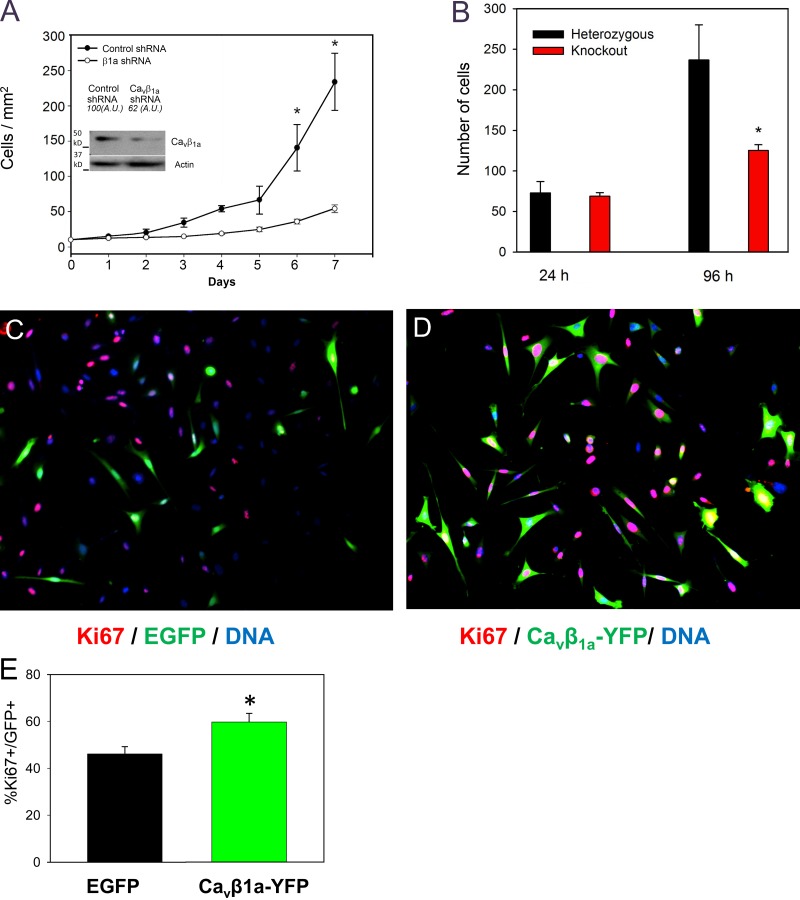

Effects of altering Cavβ1a expression on MPCs

Loss of the Cacnb1 gene in mice leads to a noticeable deficit in muscle mass in prenatal stages (Gregg et al., 1996). Though this was attributed to lack of EC coupling in myofibers, we hypothesized it may be due in part to the loss of Cavβ1a in MPCs as well. To test this, we examined the effects of knocking down Cavβ1a on C2C12 myoblast proliferation in vitro. Because C2C12 myoblasts are not excitable and do not express CaV1.1 (Fig. 1 D; Bidaud et al., 2006), any effect from reduction of Cavβ1a likely reflects a Cav-independent function of Cavβ1a. Stable transfection of cells with Cavβ1a shRNA achieved substantial reduction of Cavβ1a protein (Fig. 1 C). When observed in culture, Cavβ1a shRNA-transfected cells grew more slowly than controls. To verify this observation, clonal cultures of scrambled control and Cavβ1a-shRNA–transfected C2C12 myoblasts were plated at equal densities and then counted 24 and 48 h later. Two out of three Cavβ1a-shRNA–transfected cultures showed significantly fewer cells at 24 and 48 h compared with scrambled controls (Fig. S2). Similarly, knockdown of Cavβ1a in primary MPCs resulted in significantly impaired growth over 7 d in culture compared with controls, especially at later time points (Fig. 4 A). Cavβ1a knockdown cells showed more frequent AnnexinV-FITC staining than control cells in vitro, although the difference was not significant (P = 0.07; Fig. S3 A). To further evaluate the role of Cavβ1a in MPC proliferation, we cultured MPCs from E18.5 Cacnb1−/− embryos using FACS (Fig. S4 A). MPCs derived from Cacnb1−/− embryos also showed significantly less cell proliferation after 4 d in culture (Fig. 4 B) compared with heterozygous controls. Together, these data suggest that loss of Cavβ1a expression severely affects MPC expansion.

Figure 4.

Regulation of myoblast proliferation by Cavβ1a in vitro and in vivo. (A) Quantification of myoblast growth for 7 d after transfection with either scrambled control shRNA or Cavβ1a-targeted shRNA (Western blot of Cavβ1a knockdown is inset). (B) Quantification of MPCs cultured from Cacnb1+/− and Cacnb1−/− embryos for 4 d (n = 4). (C–E) Primary mouse myoblasts transfected with EGFP (C) or Cavβ1a-YFP (D) and stained 24 h later for Ki67 (red; n = 3). Bar, 100 µm. (E) Quantification of Ki67+/EGFP and Ki67+/Cavβ1a-YFP cells expressed as a percentage of total EGFP or Cavβ1a-YFP + cells. *, P < 0.05.

MPCs are prone to spontaneous differentiation even under proliferative conditions; thus, we hypothesized that overexpression of Cavβ1a may enhance proliferation in wild-type MPCs by preventing differentiation. To test this idea, we transfected primary MPCs with an EGFP control plasmid (Fig. 4 C) or Cavβ1a-YFP (Fig. 4 D), and then stained for the marker of proliferation, Ki67 (Gerdes et al., 1984). After 24 h in culture, a significantly higher percentage of Cavβ1a-YFP–transfected cells were also Ki67 positive, compared with EGFP/Ki67-positive cells (Fig. 4 E). Thus, increasing Cavβ1a expression level appears to enhance proliferation of MPCs, possibly by protecting against differentiation, further supporting the concept that Cavβ1a plays a critical role in MPC expansion.

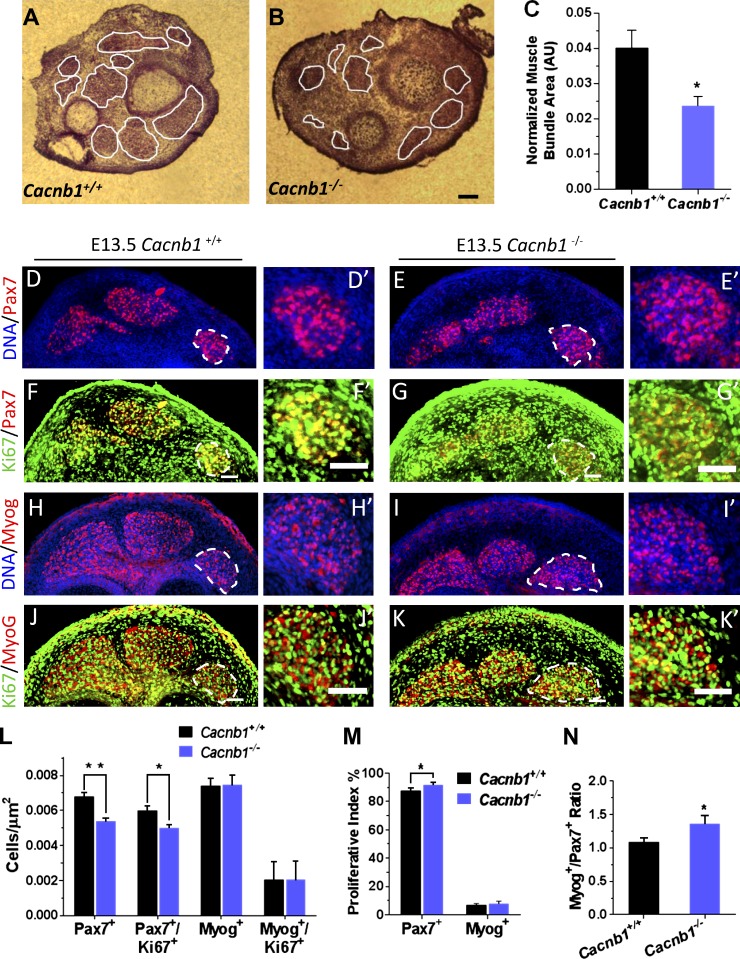

Due to the effects of Cavβ1a loss on MPC proliferation in vitro, we hypothesized that some of the deficits in muscle mass seen in Cacnb1−/− mice are due to impaired MPC proliferation, beyond the already known loss of Cav1.1 function and EC coupling. As Cacnb1−/− mice do not survive past birth, they must be studied at the embryonic stages. We chose to examine E13.5 embryos, as this time corresponds to the early stages of limb muscle development in mice, before complete innervation and large-scale muscle formation (Platzer, 1978; Ontell et al., 1995). Thus, effects from loss of EC coupling during development could be minimized, as most of the muscle cells at this time are newly formed myotubes or still in the progenitor phase. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of hind limbs from E13.5 embryos showed that the relative area of nascent muscle bundles was markedly smaller in Cacnb1−/− embryos compared with wild type, whereas the overall number of the muscle bundles was similar (Fig. 5, A–C). Thus, the deficit in muscle mass previously observed in Cacnb1−/− mice (Gregg et al., 1996) occurs very early during muscle development. To test whether impaired MPC growth contributed to the lower muscle mass seen in Cacnb1−/− embryos, we stained cross sections of Cacnb1+/+ (Fig. 5 D) and Cacnb1−/− (Fig. 5 F) hindlimbs for the MPC marker Pax7, and the proliferation marker Ki67. Compared with Cacnb1+/+, Cacnb1−/− mice had a significantly lower number of Pax7+ cells per µm2 at the same time during development (Fig. 5 L). Surprisingly, the percentage of proliferating (Ki67+) Pax7+ cells was significantly higher in Cacnb1−/− embryos (Fig. 5 M), suggesting a possible compensatory mechanism by the remaining Pax7+ MPCs. Importantly, this finding also indicates that loss of Cacnb1 expression does not impair Pax7+ MPC’s ability to divide, per se, and therefore must limit the Pax7+ MPC pool through more circuitous mechanisms. Accordingly, we measured AnnexinV-FITC/7AAD staining in E12.5 embryos by flow cytometry (Fig. S3 B) in order to see whether lower MPC numbers were due to increased rates of cell death on the preceding day. Similar to our in vitro results with Cavβ1a-shRNA in primary MPCs, Cacnb1−/− cells did not show an increase in any markers of apoptosis or necrosis. Next, we examined whether aberrant differentiation might explain reduced Pax7+ MPC pool size by quantifying the number of myogenin (a marker of terminally differentiated skeletal muscle)-positive cells in E13.5 embryos (Fig. 5, H–L). Cacnb1−/− embryos had a comparable number of myogenin+ cells to wild type, resulting in a higher ratio of myogenin+/Pax7+ cells (Fig. 5 N). The equal number of myogenin+ cells juxtaposed with smaller Pax7+ MPC pools suggests an increased preference for terminal differentiation in Cacnb1−/− embryos. Thus we conclude that loss of Cacnb1 causes aberrant and/or premature terminal differentiation, which in turn leads to depleted Pax7+ MPC pools and subsequently smaller muscle mass.

Figure 5.

Impaired skeletal muscle development in Cacnb1−/− mice. (A–C) H&E staining of early muscle bundles in E13.5 Cacnb1+/+ (A) and Cacnb1−/− (B) embryos (n = 3). Eosin positive bundles were traced, averaged, and normalized to overall cross section size (C). Bar, 100 µm. (D–N) Analysis of myogenic markers in Cacnb1+/+ and Cacnb1−/− E13.5 embryos. Cross sections from Cacnb1+/+ (D, F, H, and J) and Cacnb1−/− (E, G, I, and K) were stained for Pax7 (red) and Ki67 (green; D–G) or myogenin (red) and Ki67 (green; H–K). Nuclei (DNA) in all slides were stained blue with Hoechst dye. D′–K′ show magnified views of adjacent muscle bundles (dashed lines). Bars, 50 µm. (L) Quantification of absolute number of Pax7+ and myogenin+ cells, and absolute number of double-positive Pax7+/Ki67+ or myogenin+/Ki67+ cells, per µm2. (M) Proliferative index as measured by percentage of Pax7+ or myogenin+ cells that were also Ki67+. (N) Ratio of absolute number of myogenin+ to Pax7+ cells, per µm2. n = 3 embryos each, 3 histological sections quantified per embryo. Data are mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Chromatin binding of Cavβ1a

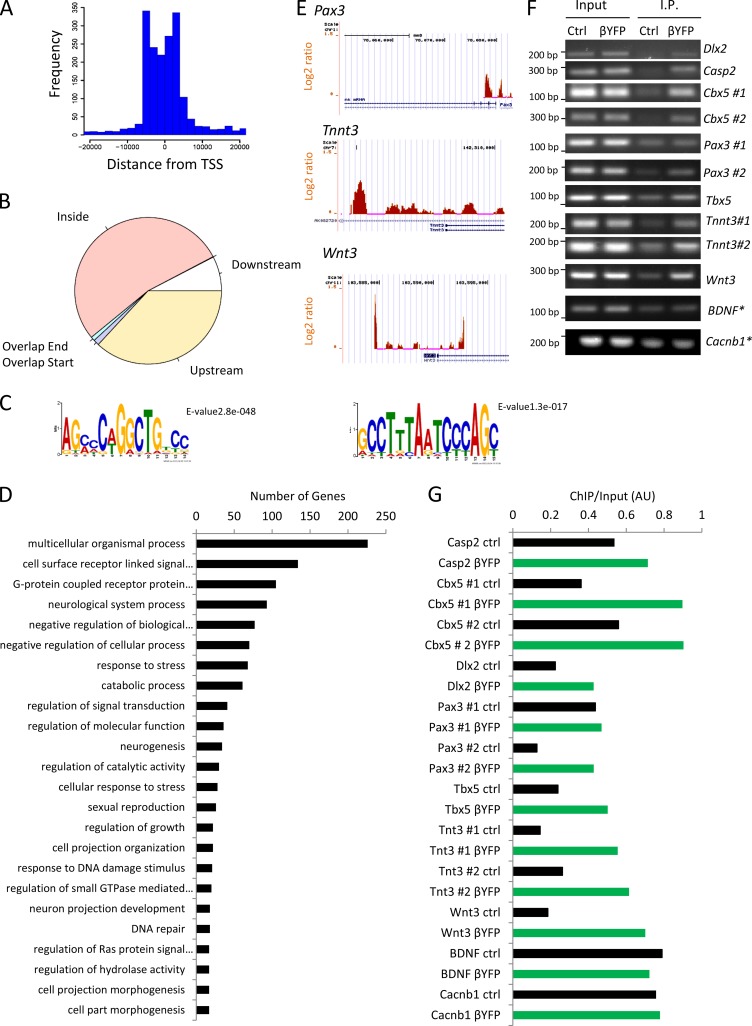

Our results demonstrate that Cavβ1a enters the nucleus of myoblasts and loss of Cavβ1a expression impairs MPC expansion. Therefore, we hypothesized that Cavβ1a may act as a transcriptional regulator. To test this question, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on-chip assays (Fig. 6). A Cavβ1a antibody was used to immunoprecipitate chromatin from C2C12 myoblasts, which was hybridized to promoter arrays containing 10-Kb coverage of 25,500 mouse genes at 35-bp resolution. Enriched Cavβ1a binding was detected in the promoter regions of 952 genes (Table S3). Binding peaks were enriched closest to the transcription start site (TSS) of most genes (Fig. 6 A), with the vast majority falling inside or upstream of the gene-coding region (Fig. 6 B). Motif analysis revealed two highly enriched DNA sequences (Fig. 6 C). The first motif contains a noncanonical, heptameric E-box sequence (CANNNTG), which has been previously reported (Virolle et al., 2002). Several other motifs containing canonical (CANNTG) and noncanonical (CANNGG, CANNTT) E-box motifs were also enriched, although to a lesser degree. The second motif contains a Bicoid-class homeodomain sequence: TAATCC (Noyes et al., 2008). Functional annotation of enriched peaks revealed Cavβ1a binds to the promoter regions of a broad set of genes, including many involved in signal transduction and stress response (Fig. 6 D). Normalized log2 (Cavβ1a/IgG) Cavβ1a-binding peaks at the promoter regions of genes of interest, namely transcription factors with known involvement in development, were visualized in the UCSC browser (Fig. 6 E). Secondary validation of these genes was tested by ChIP-PCR with a GFP/YFP antibody in untransfected and Cavβ1a-YFP–transfected myoblasts. Nearly all of the promoter regions tested showed greater than twofold enrichment, across multiple primer pairs, in the Cavβ1a-YFP–transfected cells, with the exception of negative controls (Fig. 6, F and G). Thus, Cavβ1a localizes to the promoter region of numerous genes in separate experimental designs.

Figure 6.

ChIP-on-chip analysis of Cavβ1a. (A) Histogram of Cavβ1a-binding distance from transcription start site. (B) Distribution of features of each Cavβ1a peak relative to overlapping or nearest genes. (C) Top two consensus Cavβ1a DNA-binding motifs. (D) Functional annotation of genes bound by Cavβ1a. Top 20 categories are shown. (E) Representative log2 (Cavβ1a/IgG) binding peaks on genes of interest in UCSC genome browser. Orange peaks indicate positive log2 Cavβ1a/IgG values and presumed sites of Cavβ1a chromatin binding; blue indicates negative enrichment. (F and G) Validation of ChIP-chip–identified target genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation using a GFP antibody in control and Cavβ1a-YFP–transfected C2C12 myoblasts. “#” indicates separate primer pairs used to test multiple sites on each promoter region. Asterisk indicates negative controls. Immunoprecipitated DNA intensity was normalized to input for control and Cavβ1a-YFP (G).

Global gene regulation by Cacnb1

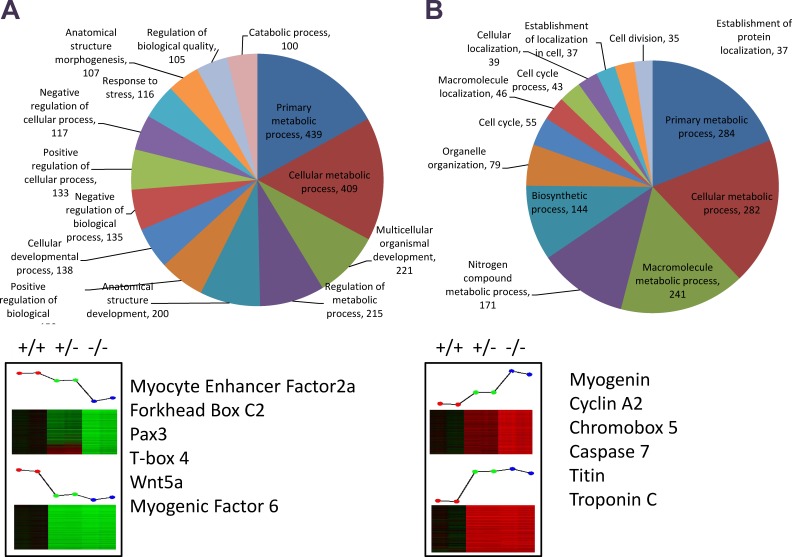

To further complement our ChIP-on-chip data, we used microarray analysis to examine changes in global gene expression in the presence or absence of Cavβ1a. Pure MPC cultures were isolated from Cacnb1+/+, Cacnb1+/−, and Cacnb1−/− mice (Fig. S4), and total RNA was extracted and used from microarray analysis (Fig. 7 and Table S5). We identified genes of interest as those that showed significant fold change in a Cacnb1 dose-dependent manner. Specifically, we identified 1,104 genes that decreased with decreasing Cacnb1 expression (negatively regulated by Cacnb1; Fig. 7 A) and 1,888 genes that increased with decreasing Cacnb1 expression (positively regulated by Cacnb1; Fig. 7 B). One gene negatively regulated by Cacnb1 (increased in Cacnb1−/−) of particular interest was the transcription factor myogenin (Myog). Myogenin is known to play a critical role in skeletal muscle development, and intriguingly was found in an increased ratio to Pax7+ cells in our exploration of early muscle development in Cacnb1−/− embryos. Further functional analysis highlighted many genes involved in cell cycle regulation and muscle development (Fig. 7, A and B). Of the genes identified from ChIP-on-chip, 40 showed increased expression in Cacnb1−/− cells, whereas 70 showed decreased expression, indicating that Cavβ1a may act as both a positive and negative regulator of gene expression at the chromatin level (Table S6).

Figure 7.

Microarray analysis of Cacnb1 wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and knockout (−/−) MPCs. Genes were selected based on dose-dependent correlation with Cacnb1 expression. Genes said to be up-regulated by Cacnb1 are lowest in −/− cells and functionally annotated in A, whereas genes said to be down-regulated by Cacnb1 are highest in −/− cells and functionally annotated in B. GOTERM “other” (1,640 for A and 234 for B) was omitted from charts in order to improve visibility of other categories. Genes of interest involved in cell cycle and muscle development are listed below pie charts. See also Fig. S3 and Table S4.

Cacnb1 regulates Myog

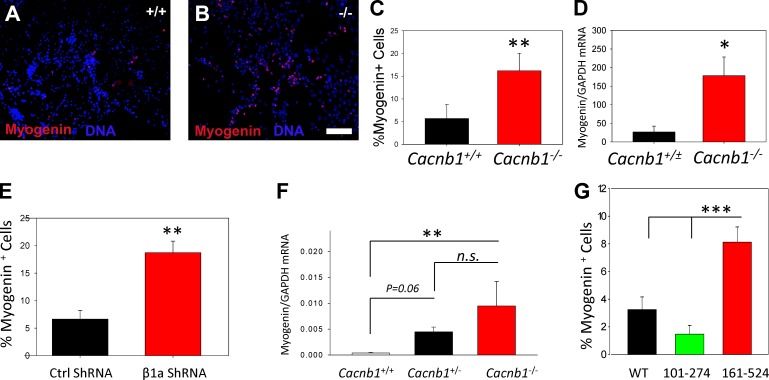

Myogenin acts as a switch for MPCs to transition from proliferation to differentiation, and previous studies have shown that precocious expression of myogenin can lead to MPC pool depletion (Schuster-Gossler et al., 2007; Van Ho et al., 2011). We therefore hypothesized that if Myog is inhibited by Cavβ1a, then the impaired MPC growth we observed when Cavβ1a was knocked down/out was due to aberrant myogenin expression in these cells. To confirm our microarray results, we generated myogenic explant cultures from E18 embryos and quantified myogenin expression using immunocytochemistry (Fig. 8, A–C) and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 8 D). After 3 d, cultures from Cacnb1−/− embryos had significantly more myogenin-positive cells than Cacnb1+/+ (Fig. 8 C). Myogenin mRNA was also approximately sevenfold higher overall in Cacnb1−/− cultures compared with Cacnb1+/+ and Cacnb1+/− (Fig. 8 D). Similarly, primary MPC cultures transfected with Cavβ1a shRNA showed a significantly higher percentage of myogenin-positive cells compared with controls (Fig. 8 E). To test whether loss of Cacnb1 increases myogenin in MPCs in vivo, we measured myogenin mRNA in the hindlimb buds of E11.5 Cacnb1+/+, Cacnb1+/−, and Cacnb1−/− embryos (Fig. 8 F) at a time which predates differentiated muscle formation in the developing limb (Taher et al., 2011). Myogenin mRNA was ∼10-fold and 25-fold higher in the limb buds of Cacnb1+/− and Cacnb1−/− embryos, respectively, compared with wild-type controls. Together, these results demonstrate that loss of Cavβ1a results in increased myogenin mRNA and protein, thus validating our microarray data, and also suggesting that Cavβ1a acts to inhibit myogenin expression. To test whether this inhibition was dependent on Cavβ1a nuclear entry, we used Cavβ1a-YFP mutants, which had shown the strongest and weakest nuclear localization (Fig. 3). Compared with full-length Cavβ1a-YFP, Cavβ1a-101-274-YFP (lacking GK domain and constitutively nuclear) showed an enhanced ability to suppress myogenin expression in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts, whereas Cavβ1a-161-524-YFP (lacking SH3 domain and constitutively cytoplasmic) was much less effective at inhibiting myogenin expression (Fig. 8 G).

Figure 8.

Cacnb1 modulates Myog expression in muscle progenitors. Representative images from Cacnb1+/+ (A) and Cacnb1−/− (B) E18.5 hindlimb explants cultures after 3 d in vitro. Bar, 100 µm. Cultures were then fixed and stained for myogenin (C; n = 5 and 3) or analyzed by quantitative PCR (D; n = 3 each, note that Cacnb1+/+ and Cacnb1+/− are pooled). (E) Quantification of myogenin-positive cells in control and Cavβ1a-shRNA–treated primary MPC cultures (n = 3 each). (F) qPCR for myogenin mRNA from hindlimb buds dissected from Cacnb1+/+, Cacnb1+/−, and Cacnb1−/− E11.5 embryos (n = 6–12 each). (G) Quantification of myogenin expression in differentiating (1 d DM) C2C12 myoblasts, transfected with full-length, nuclear (101–274), or cytoplasmic (161–524) Cavβ1a-YFP constructs (n = 6 each). Data are ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

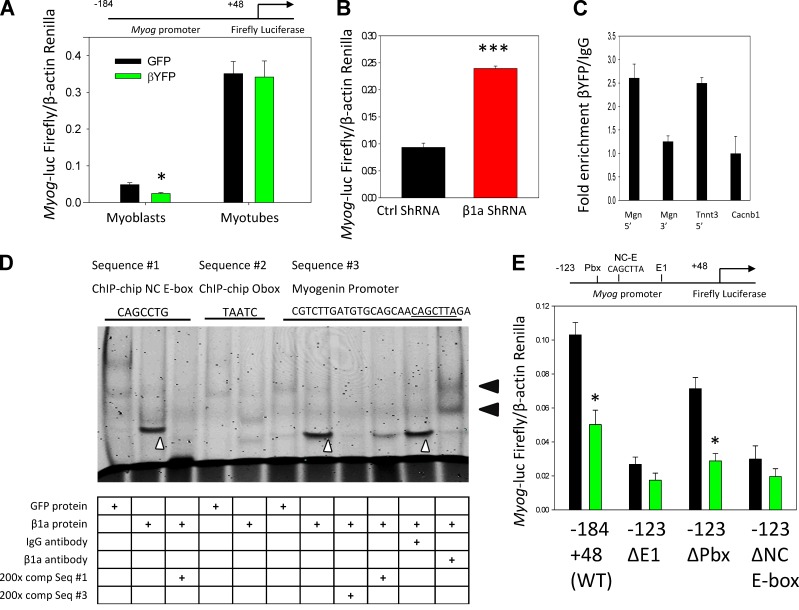

We next sought to determine how Cavβ1a regulates myogenin expression, hypothesizing that Cavβ1a may interact with the Myog promoter. To initially test this idea, we made use of a luciferase reporter gene linked to a core region of the myogenin promoter (−184 +44; Myog-luc; Berkes et al., 2004). When Myog-luc–expressing C2C12 myoblasts were cotransfected with Cavβ1a-YFP, we saw decreased reporter gene activation compared with EGFP-transfected controls (Fig. 9 A), suggesting that Cavβ1a represses myogenin gene expression via direct or indirect actions on the Myog promoter region. After two days in differentiation medium, Cavβ1a-YFP no longer suppressed Myog-luc activity, indicating that the Myog promoter escapes Cavβ1a regulation after terminal differentiation (Fig. 9 A). Conversely, C2C12 myoblasts cotransfected with Myog-luc and Cavβ1a shRNA showed significantly higher luciferase activation than controls (Fig. 9 B). Thus, loss of Cavβ1a protein enhances activation of the Myog promoter. In addition, ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 9 C) of Cavβ1a-YFP showed specific enrichment of the proximal Myog promoter, but not a region of intragenic DNA 3′ to the Myog gene. Although modest (approximately twofold), this level enrichment was comparable to Cavβ1a binding at the TnnT3 promoter region that we identified from our ChIP-on-chip experiments, versus another unbound region located in exon 5 of the Cacnb1 gene (Fig. 9 C).

Figure 9.

Cavβ1a action at the Myog promoter. (A) Myog-luc expression in GFP (black) or Cavβ1a-YFP (green) expressing myoblasts (n = 5) and myotubes (n = 6). (B) Myog-luc expression in control (black) and Cavβ1a-shRNA (red)–transfected C2C12 myoblasts (n = 3). (C) ChIP-qPCR showing relative fold enrichment of Cavβ1a-YFP pull-down of Myog promoter (Mgn 5′) and Tnnt3 promoter (Tnnt3), with Myog 3′ region (Mgn 3′) and Cacnb1 exon 5 (Cacnb1) as controls. (D) Gel shift assay using GFP protein (control) or Cavβ1a-YFP protein from Cos7 nuclear extracts. Mouse IgG is nonspecific antibody. A specific shift can be seen in lanes 2, 7, and 10 (white carats), and supershift induced by YFP antibody seen in lane 11 (black arrowheads). Fluorescently labeled probe sequences (top) were generated from ChIP-chip motif results (sequences #1 and #2) and from the Myog promoter (sequence #3; NC E-box motif underlined). Full probe sequences are available in Table S1. (E) Mutation analysis of Myog promoter. C2C12 were transfected with GFP (black) or Cavβ1a-YFP (green) and then wild-type (−184 +48) Myog-luc, or −123 +48 fragments with mutations in E1 E-box (ΔE1), Pbx1 (ΔPbx), or noncanonical E-box (ΔNC E-box; CAGCTTA sequence indicated in D has been mutated to TGGCTTA) Myog-luc constructs, n = 3 per group. Locations of mutations are indicated above. See Berkes et al. (2004) for origin of these constructs. Data are ± SEM; *, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

The proximal Myog promoter contains several conserved transcription factor–binding sites, leading us to examine which site(s) Cavβ1a might act on within this region. Motif analysis from our ChIP-on-chip data led us to investigate both canonical and noncanonical E-boxes, and homeobox motifs within the core (−184 +44) Myog promoter. In electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), addition of Cavβ1a-YFP protein caused a specific shift of a probe containing the NC E-box from our ChIP-on-chip consensus motif (9D). However, a probe containing the secondary homeodomain-binding motif (TAATCC) was not shifted by Cavβ1a-YFP. A probe from a portion of the Myog promoter containing both a homeodomain site (Pbx) and an adjacent NC E-box (CAGCTTA) similar to our consensus motif was shifted by Cavβ1a-YFP protein, and supershifted by addition of a GFP/YFP antibody. Importantly, the shift induced by Cavβ1a-YFP to the Myog promoter probe could be almost completely erased by using our ChIP-on-chip–identified NC E-box sequence as a competitor. Thus, Cavβ1a appears to interact with a heptameric NC E-box motif located in the proximal Myog promoter, although the higher affinity of Cavβ1a-YFP for the Myog promoter sequence than for our consensus motif suggests this fragment of the Myog promoter may contain additional sequences important for Cavβ1a binding. To better understand the relationship between Cavβ1a-YFP, canonical and noncanonical E-boxes, and homeodomain motifs, within the context of Myog promoter activity, we used Myog-luc mutant constructs (Berkes et al., 2004). Mutation of both canonical and noncanonical E-box motifs attenuated Cavβ1a-YFP–induced inhibition, whereas mutation of the homeodomain/Pbx-binding site actually enhanced inhibition by Cavβ1a-YFP (Fig. 9 E). We conclude that Cavβ1a binds to the proximal Myog promoter at a specific NC E-box motif, and that its binding affinity may be regulated by complex involvement from nearby homeodomain and E-box sites.

Because of its apparent involvement with canonical and noncanonical E-box sites, as well as homeodomain sites, we tested the ability of Cavβ1a-YFP to interact with E-box and homeodomain proteins known to bind to the Myog E-box–binding proteins. MyoD (Cheng et al., 1992), Mef2 (Edmondson et al., 1992), and homeodomain proteins Lef-1 (not expressed in myoblasts; Fig. S5 A) and Pbx1 (Berkes et al., 2004) all failed to co-precipitate with Cavβ1a-YFP (Fig. S5 B). Expression of Cavβ1a-YFP did not alter the subnuclear localization of MyoD or Mef2 (Fig. S5 C), suggesting that Cavβ1a does not act on the Myog promoter in concert with any of these proteins. Together, these results indicate that Cavβ1a does not bind the Myog promoter as part of a complex with MyoD, Mef2, or Lef-1, suggesting an interaction with other proteins.

Discussion

Cavβ1a has long been known solely for its essential role in skeletal muscle EC coupling. Though a few reports have intimated roles for the protein as a transcriptional regulator, a well-defined physiological context for Cavβ subunits outside of Cav-regulation has yet to be established. Here we show that the Cavβ1a subunit regulates skeletal muscle myogenesis in vivo during embryonic development via repressive actions on the Myog promoter in MPCs.

The idea of Cav-independent roles for Cavβ subunits has been suggested previously, which has been mainly tied to their nuclear translocation. Cavβ4c and Cavβ3 subunits have been shown to regulate transcription in vitro by direct suppression of Hp1 (Hibino et al., 2003) and Pax6(s) (Zhang et al., 2010), respectively, in a Cav-independent fashion. A precise physiological role for Cav-independent functions of Cavβ subunits has been elusive, but a few recent clues have emerged. Garrity and colleagues have also shown effects of morpholino-mediated Cavβ knockdown in zebrafish models: knockdown of Cavβ4 prevented normal epiboly in early zebrafish embryos, which could be rescued by a Cav-binding–deficient mutant Cavβ4 (Ebert et al., 2008). Interestingly, this group also found impaired cardiac progenitor cell proliferation in 24–30 and 30–36 h post-fertilization zebrafish embryos after Cavβ2 knockdown (Chernyavskaya et al., 2012). The latter finding is especially compelling in the context of our findings that Cavβ1a knockdown/gene knockout in muscle progenitor cells impairs their expansion in vitro and in vivo. Cavβ subunits may also have distinct nuclear functions in mitotic versus post-mitotic cells, as evidenced by recent papers showing specific actions for Cavβ4 in the nucleus of cerebellar neurons (Subramanyam et al., 2009; Tadmouri et al., 2012). An interesting future direction will be to explore the potential nuclear role of Cavβ1a in differentiated skeletal muscle.

A foundation of our study was the novel finding that Cavβ1a enters the nucleus of MPCs. An important question that remains is how do Cavβ1a, and Cavβ subunits, in general, travel to the nucleus? One possibility is that Cavβ subunits bind to other proteins, either in a conserved or isoform/tissue-specific fashion. Earlier works with other Cavβ subunits offered several different protein-binding partners that may be responsible for their nuclear translocation, including the aforementioned Hp1 and Pax6(s) proteins, as well as the RGK (Rad, Rem, Gem/Kir) family of proteins (Buraei and Yang, 2010), and B56δ and PP2A (Tadmouri et al., 2012). In our own assays, neither Hp1 nor the RGK protein Rem coprecipitated with Cavβ1a-YFP (unpublished data). We also did not see evidence of Cavβ1a interaction with Lef1 or several other proteins also known to regulate the Myog promoter (MyoD, Mef2, Pbx1), leaving this as an open question.

Another possibility is that Cavβ enters the nucleus based on an NLS specific to one or more isoforms of the protein. We believe this to be less likely, as Cavβ subunits do not possess a classical NLS, and truncation of a lysine/arginine-rich putative yeast NLS (Hicks and Raikhel, 1995) does not affect nuclear localization of our Cavβ1a-YFP constructs. Our work and other studies (Hibino et al., 2003; Takahashi et al., 2005) highlight the importance of the SH3 domain for Cavβ nuclear translocation. The apparent importance of the SH3 domain in nuclear localization across Cavβ isoforms suggests that this phenomenon is conserved, yet the individualized preference of Cavβ isoforms for nuclear binding partners paradoxically argues in favor of isoform-specific mechanisms of nuclear translocation. The SH3 domain contains a PxxP binding motif (Buraei and Yang, 2010), and may therefore bind multiple NLS-containing proteins in a tissue-specific fashion, offering a possible way to reconcile these findings.

Reduced skeletal muscle mass has been associated with loss of the Cacnb1 gene since the original creation of the knockout mouse (Gregg et al., 1996). This phenotype was viewed as similar to that seen in the dysgenic (Cav1.1 mutant; Pai, 1965; Knudson et al., 1989; Chaudhari, 1992), and dyspedic (RyR mutant; Takeshima et al., 1994), and therefore attributed to lack of EC coupling during development. Although the initial report looked at mice in the late prenatal stage (E18), we observed deficits in Cacnb1−/− muscle mass as early as E13.5, suggesting a sustained impairment during early muscle development. We also observed fewer Pax7+ MPCs in Cacnb1−/− hindlimbs, a deficit which cannot be explained by lack of EC coupling. Furthermore, myogenin mRNA was increased in the limb buds of E11.5 mutant mice, at a time that predates myotube formation (Taher et al., 2011) and thus EC coupling. It is possible that Cavs play some other role in MPC proliferation/expansion, beyond EC coupling. However, this appears unlikely, as our data from C2C12 myoblasts showed both the complete absence of Cav1.1 expression and the absence of Cavβ1a membrane localization, together suggesting the total absence of any functional Cavs in MPCs. Additionally, a previous report found no differences in the growth rate of MPCs isolated from wild-type and dysgenic mice (Pinçon-Raymond et al., 1991).

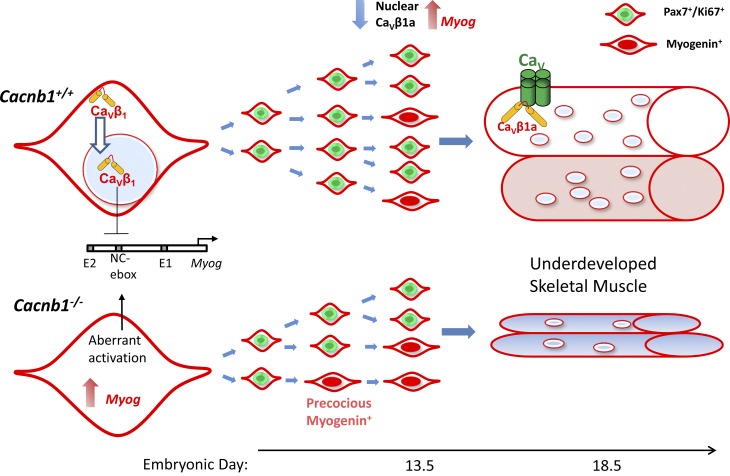

A key concept in the field of skeletal muscle development and regeneration is the need for precise balance between progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Terminal differentiation (e.g., myogenin expression) of MPCs is closely associated with their exit from the cell cycle, recently underscored by work showing that myogenin promotes the expression of the anti–cell cycle miRNA20a (Liu et al., 2012). Therefore, suppression of differentiation proteins, such as myogenin, is critical for normal MPC expansion. Several works in mutant mouse models (Schuster-Gossler et al., 2007; Van Ho et al., 2011) show that a decreased number of Pax3/Pax7+ MPCs during development is associated with an increase in myogenin+, and presumably terminally differentiated cells. This is consistent with our findings that Cacnb1−/− mice show a higher ratio of myogenin+/Pax7+ MPCs in hindlimbs at E13.5, which is preceded by significantly higher myogenin mRNA in hindlimb buds at E11.5. Based on our data, we propose a mechanism for this pathway by which Cavβ1a acts at the Myog promoter region to suppress its transcription (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Mechanism of CaVβ1a regulation of myogenesis. In Cacnb1+/+ MPCs, CaVβ1a enters the nucleus and acts on an NC E-box on the Myog promoter, suppressing Myog expression and allowing Pax7+ MPCs to proliferate in sufficient quantity. Following differentiation cues, CaVβ1a exits the nucleus and Myog is disinhibited, allowing terminal differentiation and fusion of myotubes. In Cacnb1−/− MPCs, Myog is not properly suppressed, leading to increased probability of Myog up-regulation and precocious differentiation. The number of myogenin-expressing cells is initially higher, but because their formation also depletes the Pax7+ progenitor pool, there are fewer precursors to form myogenin-positive cells at later time points. The final result is underdeveloped skeletal muscle.

The question of exactly how Cavβ1a regulates the Myog promoter is complex. Our ChIP-on-chip experiment did not identify Myog as a gene bound by Cavβ1a, yet our ChIP-qPCR and EMSA results indicated it was. A possible reconciliation for these findings is that Cavβ1a binds weakly or transiently to Myog (in agreement with our relatively low ChIP-qPCR enrichment), and perhaps acts to displace or rearrange a larger protein complex. The primary DNA consensus motif discovered for Cavβ1a was an NC (heptameric) E-box, followed by a Bicoid-class homeodomain motif. In addition, several hexameric NC E-boxes were identified (unpublished data). Cavβ1a-YFP bound to NC E-box sequences in EMSAs, but not homeodomain motifs, suggesting a selective association with E-box or NC E-boxes found adjacent to homeodomain sequences, while not acting directly on the homeodomain sequences themselves. The Myog promoter contains such an arrangement (Berkes et al., 2004), and EMSA and Myog-luc assays provided strong evidence that Cavβ1a localizes and acts on this element of the Myog promoter.

It is important to note that whereas Cavβ1a inhibits myogenin expression in MPCs, Cavβ1a expression actually increases during myogenic differentiation in vitro, a period well known to be marked by a transient increase in myogenin expression. Therefore, under normal circumstances it seems that the Myog promoter finds a way to escape Cavβ1a-mediated inhibition during differentiation. The apparent decline in Cavβ1a nuclear localization with myogenic differentiation offers a partial mechanism for this escape, although some visible Cavβ1a apparently remains in the nucleus of differentiated myotubes, suggesting additional regulatory mechanisms. The identification of cofactors involved in Cavβ1a regulation of the Myog promoter is critical for addressing this question.

Our work describes a highly novel role for Cavβ1a in MPCs, from the molecular to physiological level. The specific function of Cavβ1a in skeletal muscle and the generalized role (if any) for all Cavβ subunits in the nucleus are both important lines of research, and both should offer important insight into basic cellular function and human health and disease.

Materials and methods

RT-PCR and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells and tissue using TRIzol reagent. Primer sequences used for RT-PCR and ChIP-PCR, as well as product numbers for real-time TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems) are listed in Table S1. For real-time PCR, gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). mRNA was primed with random hexamers and reverse transcribed with Reverse Transcription III (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed on a GeneAmp PCR System 3700 (Applied Biosystems) under the default parameters for 35 cycles. For real-time PCR, samples were prepared using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan probes (Table S1) on a qPCR system (Mx3000P; Agilent Technologies), using the default parameters for 35 cycles.

Protein isolation and Western blot

Cytosolic and membrane fractionation were based on previous protocols (Leung et al., 1987; Taylor et al., 2009). In brief, C2C12 cells were collected with a rubber scraper, rinsed in ice-cold PBS, and lysed in ice-cold buffer A (20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 303 mM sucrose with complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) using a handheld glass homogenizer. Homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 90 min at 4°C in a rotor (model Ti 70i; Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was saved as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was rinsed with ice-cold PBS and resuspended with a glass homogenizer in fresh digitonin buffer (1% digitonin [wt/vol], 185 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, with complete protease inhibitor cocktail) as the membrane fraction.

For cytosolic and nuclear fractions, C2C12 myoblasts were lysed in Ontell buffer (Washabaugh et al., 2007; 19 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, and 0.1% Triton X-100; 300 µl buffer per 100 mg tissue) using 50–100 strokes of a glass homogenizer. Lysate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and supernatant was taken as cytosolic fraction. Pellet was rinsed twice in Ontell buffer, then resuspended in buffer 2 (0.5 M sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM DTT, and 0.6 M KCl) as the nuclear fraction.

Protein concentration was measured using Bradford or bicinchoninic protein assays with bovine serum albumin standards.

For Western blotting, proteins samples were mixed with 2× Laemmli buffer (2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 0.125 M Tris, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol; Laemmli, 1970). Samples to be probed for Cav1.1 were loaded in 8 M Urea buffer (8 M Urea, 20% SDS, 50 mM Tris, 0.004% BPB, 2 M Thiourea, and 1 mM DTT), boiled at 95°C for 5 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE using 10% polyacrylamide gels with 4.5% stacking gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and blotted using 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS + 0.02% Tween 20 for all antibody incubation steps. Proteins were visualized with ECL Plus (GE Healthcare).

Antibody clone, dilution, and product numbers are listed in Table S2.

Construction of recombinant adenoviral vector RAd-Cavβ1a-YFP

cDNA for Cavβ1a-EYFP (GenBank accession no. M25514.1, donated by K. Beam, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO; Leuranguer et al., 2006) was inserted into a RAd vector by a variant of the two-plasmid method (Hitt et al., 1998) using the AdMax plasmid kit (Microbix). cDNA coding for Cavβ1a-YFP was excised from plasmid Cavβ1a-YFP (with EcoR I and Hpa I at the 5′ and 3′ end, respectively) and inserted in the multiple cloning site (MCS) of shuttle pDC516 (one of the shuttle plasmids in the kit), which contains an expression cassette consisting of the mouse cytomegalovirus promoter (mCMV) and the simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation signal, immediately upstream and downstream of the MCS, respectively. Downstream of this cassette, pDC516 also contains an frt recognition site for the yeast FLP recombinase. The second plasmid of the kit, the genomic plasmid pBHGfrt(del)E1,3 FLP, consists of the entire genome of adenovirus 5 (Ad5), with deletions in the E1 and E3 regions. Upstream of the E1 deletion, pBHGfrt(del)E1,3 FLP contains an expression cassette for the gene for yeast FLP recombinase, and immediately downstream the E1 deletion there is an frt recognition site. Both plasmids were cotransfected in HEK293 cells, a line stably transfected with a portion of the Ad5 E1 genomic region. In cotransfected HEK293 cells, FLP recombinase is readily expressed and efficiently catalyzes the site-directed recombination of the expression cassettes of pDC516 into the left end of pBHGfrt(del)E1,3 FLP, thus generating the genome of the desired recombinant adenoviral vector, RAd-Cavβ1a-YFP. The newly generated RAd was rescued from HEK293 cell lysates, plaque purified, and then purified by ultracentrifugation in CsCl gradient and dialyzed. Final virus stock was titrated by a serial dilution plaque assay. RAd-GFP control was purchased from the UNC Vector Core Facility (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC).

Histology and immunofluorescent staining

Animal housing and procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Wake Forest Health Sciences. For timed embryo studies, breeding pairs were placed together overnight and separated the following morning. Pregnancy was confirmed by sustained weight gain over the next 10 days. Genotypes were confirmed by PCR. Hindlimbs from E13.5 embryos (n = 3 per genotype) were removed from the whole body and placed in disposable embedding molds containing cold PBS. Then, they were cryopreserved by sucrose gradient (0.25 M sucrose in PBS for 1 h, 0.5 M sucrose in PBS for 45 min, and finally 1.5 M sucrose in PBS for 30 min), embedded in tissue-freezing medium (Triangle Biomedical Sciences, Inc.), and frozen in dry ice–chilled isopentane. Tissue blocks were stored at −80°C until sectioning (modified from Le Grand et al., 2004). For immunofluorescent staining, cells and 12 µM transverse cryosections were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBST (0.05% Tween 20). Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed in embryo sections for Pax7 antigen using a steam pressure–based system (2100 Retriever; PickCell Laboratories) and a modified citrate buffer commercially available (R-Buffer A; Electron Microscopy Sciences). Once the retrieval cycle was completed, the slides were allowed to cool down inside the machine for at least 40 min. After antigen retrieval, slides were rinsed with PBST, blocked in 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C (see Table S2). Because both anti-Pax7 and anti-myogenin antibodies derived from a mouse host equivalent/analogous slides were chosen for each hindlimb and staining was performed separately for these antigens. Anti-Ki67 and nuclear staining (Hoechst) were included in every case. Slides were mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako). Hematoxylin Gill no. 2 and Eosin Y (Sigma-Aldrich) solutions were used for H&E staining, and slides were mounted with Cytoseal (Thermo Fisher Scientific). LMB (LC Laboratories) was added to culture medium at 20 nM for 3 h before fixation or lysate collection. For the E13.5 embryo immunostaining, one hindlimb of each subject was sectioned in order to completely span the region between the future knee and ankle. The tibia and fibula were used as reference to identify the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and peroneus brevis/longus developing muscles. A total of three sections per hindlimb containing these three muscle bundles were analyzed for every combination of antigens. Images were captured on a microscope (IX81; Olympus) with an Orca TC2 camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) at room temperature and analyzed using MetaMorph Basic software. Objective lenses used were: UPLFLN 10× 2PH; U PLAN FL 10× Phase OBJ, NA 0.3; IPLSAPO 20×; U PLAN S-APO 20×, NA 0.75 (Olympus). Each bundle perimeter was delimited based on discreet clusters of Pax7 or myogenin staining and the area was calculated. The number of Pax7+ and myogenin+ nuclei within was determined using MetaMorph. Co-labeling of Pax7 or myogenin and Ki67 was determined by additive image overlay in the same software. All counting experiments were performed with the operator blind to experimental conditions.

Cell death analysis and flow cytometry

Cells were isolated from hindlimbs of E12.5 embryos by enzymatic digestion, pre-plated for 1 h on plastic, and stained for AnnexinV-FITC and 7AAD for 15 min at room temperature. Flow cytometry was performed on a flow cytometer (Accuri B6; BD).

Molecular cloning

Cavβ1a-YFP truncation mutants were cloned by PCR using primer pairs containing EcoR1 and SalI restriction enzyme digest sequences (listed in Table S1) and inserted into the pEYFP_n1 vector (Takara Bio Inc.). Sequencing confirmed all constructs (DNA Sequencing Laboratory, Wake Forest University Health Sciences [WFUHS]).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), primary cell culture, and transfection

C2C12 (ATCC) myoblasts were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). FACS was performed as described previously (Griffin et al., 2010) in a FACSAria (BD). Embryos were harvested at E18.5 under sterile conditions. Skeletal muscle was dissected from the limbs, minced, washed in ice-cold PBS, and incubated in a collagenase type II/dispase I solution for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then triturated, passed through a 40-µm nylon mesh filter, washed, and labeled with α7-integrin APC and CD31/CD45-FITC–conjugated antibodies in PBS with 1% FBS for 30 min at 4°C and washed twice before FACS. MPCs were cultured on laminin (Invitrogen)-coated dishes in Ham’s F10 medium with 20% FBS and basic FGF (5 ng/ml, Promega; Rando and Blau, 1994). Differentiation was induced upon C2C12 myoblasts or MPCs reaching 90% confluence by placing cells in DMEM with 2% horse serum. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for transfection. 5 Cavβ1a-specific shRNA sequences from the RNAi Consortium (Open Biosystems) were individually tested in C2C12 myoblasts selected with 3 ng/µl puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). TRC 69052 showed the highest efficacy of Cavβ1a protein knockdown and was used for further experiments. MISSION SHC002 nontargeting shRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a control. Explant cultures were prepared from E18.5 mice as described previously (Smith and Merrick, 2010). In brief, hindlimb muscles were dissected and cut into roughly 1-mm3 cubes, which were then placed in 96-well culture dishes with growth medium for 3 d.

Microarray

Total RNA was prepared from FACS-sorted primary Cacnb1 +/+, +/−, and −/− MPCs and hybridized to GeneChip Mouse Genome 430A 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix) according to manufacturer’s instructions at the WFUHS Microarray Core Laboratory. CEL files were analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite (Partek) and grouped into nine categories of expression based on fold change between the three experimental groups. Functional annotation was performed using DAVID v6.7 software using GOTERM_BP_2 (Huang et al., 2009).

Luciferase assay

C2C12 myoblasts were infected with RAd Cavβ1a-YFP or RAd-GFP and 24 h later transfected with pMyog-firefly luciferase (a gift from S. Tapscott, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA; Berkes et al., 2004) and β-actin–Renilla luciferase. Cells were checked for equal density and viral transfection and harvested 12 h later at confluence in GM, or after 48 h in DM, and normalized firefly to Renilla luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega).

ChIP-on-chip and ChIP-PCR/qPCR

Chromatin was immunoprecipitated from subconfluent C2C12 myoblasts using a Cavβ1a antibody (H-50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or control rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), hybridized to GeneChip mouse promoter 1.0R arrays (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For ChIP buffer recipes, see Table S3. In brief, 5 × 107 C2C12 myoblasts were fixed in formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% for 10 min, quenched with 2.5 M glycine, washed with PBS, and collected with a rubber cell scraper. The pellet was washed three times in lysis buffer, resuspended in Pre-IP dilution buffer, and sonicated for 10 × 60 s on ice. Average chromatin fragment size was confirmed on an agarose gel to be 200–1,000 bp before proceeding. Chromatin was precleared with protein A–Sepharose beads, then incubated overnight with antibodies at 4°C. The next day, chromatin was incubated with protein A–Sepharose beads for 4 h at room temperature. Beads were pelleted and washed with ChIP washes 1 and 2 (twice each for 5 min), ChIP wash 3, TE, and finally chromatin was eluted twice with elution buffer at 65°C. Cross-linking was reversed by incubation with proteinase K overnight at 65°C, and DNA purified using cDNA Cleanup Columns (Affymetrix). DNA was randomly primed using Sequenase and primer A (GTTTCCCAGTCACGGTC(N)9; HPLC purified) and amplified using primer B (GTTTCCCAGTCACGGTC) and Taq polymerase. Amplification of fragments sized 200–2,000 bp was confirmed on an agarose gel. Samples were purified on a GeneChip Sample Cleanup Module (GE Healthcare). For ChIP-on-chip, DNA was fragmented, labeled, and hybridized to mouse promoter 1.0R arrays (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

ChIP-PCR/qPCR

ChIP-PCR/qPCR was performed using an anti-GFP antibody (see Table S2) for immunoprecipitation, following the same protocol used for ChIP-on-chip. Primers were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST. ChIP-PCR was performed on a GeneAmp PCR System 3700 (Applied Biosystems) under the default parameters for 35 cycles. ChIP-qPCR was performed on a qPCR system (Mx3000P; Agilent Technologies), using the default parameters for 40 cycles.

EMSA

Nuclear protein extracts were prepared from Cos7 cells (Holden and Tacon, 2011), expressing either GFP or Cavβ1a-YFP, and incubated with infrared dye–labeled oligos (see Table S1) for 30 min at room temperature, and an additional 30 min with antisera or an equivalent volume of PBS. Samples were run on 4–12% nondenaturing TBE gels.

ChIP-on-chip analysis

The average log2 (Cavβ1a/IgG) intensity value of the two biological replicates was computed for each probe position. Regions enriched for Cavβ1a relative to IgG were determined using CMARRT (Kuan et al., 2008) on the average log2 (Cavβ1a/IgG) at the FDR level of 0.05. Peak annotation, distance to TSS, and position to nearest gene were performed using ChIPpeakAnno (Zhu et al., 2010) and the Galaxy web platform (Blankenberg et al., 2010; Goecks et al., 2010). Refseq ID conversion to gene names and functional annotation were performed using DAVID v6.7 GOTERM_BP_ALL (Huang et al., 2009). For distance to TSS and peak position relative to nearest gene, peak coordinates were lifted over from mm8 to mm9 and then mapped to either the nearest or overlapping genes using the prebuilt transcription start sites annotation library for mouse genome TSS.mouse.NCBIM37. Peaks (log2 Cavβ1a/IgG intensity) were visualized in BedGraph format using the UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al., 2002; University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). Motif analysis was performed with MEME software (Bailey et al., 2009) and TOMTOM (Gupta et al., 2007).

For peak position, peaks not overlapping with a gene were tied to the nearest feature when generating the pie chart. “Overlap Start” and “Overlap End” correspond to peaks that overlap with gene transcription start and end site, respectively. “Upstream” and “Downstream” correspond to peaks that are upstream of gene transcription start site and downstream of gene transcription end site, respectively. “Inside” corresponds to peaks that are within gene region. “Inside” corresponds to peaks that cover the entire gene (especially for very short genes).

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed using SigmaPlot v11.0 with Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA repeated measures, with Holm-Sidak test applied post hoc when appropriate. An α-value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows representative images of all Cavβ1a-YFP mutants with and without LMB treatment. Fig. S2 shows the effect of shRNA-mediated knockdown of Cavβ1a in myoblast expansion in vitro. Fig. S3 shows the analysis of cell death in Cavβ1a knockdown and Cacnb1−/− cells. Fig. S4 shows isolation strategy of muscle precursor cells from E18.5 embryos using FACS. Fig. S5 shows the screening for Cavβ1a-binding partners at the Myog promoter using Co-immunoprecipitation and fluorescent colocalization. Table S1 lists the primers used throughout the paper for various functions (RT-PCR, cloning, shRNA, etc.). Table S2 lists the antibodies used throughout the paper for various experiments (Western blot, immunocytochemistry, immunohistochemistry, ChIP). Supplier, clone, antigen, host, and dilutions are included. Table S3 lists the buffers used in ChIP. Table S4 is a complete list of genes with promoter regions found to be enriched for Cavβ1a binding, and is related to Fig. 6 of the main text. Table S5 is a complete list of genes found to be differentially regulated by microarray analysis, between our three experimental groups. Genes are subdivided into the nine different patterns shown in Fig. S3. Table S5 is related to Fig. 7 of the main text. Table S6 displays a list of genes with promoter regions found to be ChIP enriched for Cavβ1a binding and also showing differential regulation in expression by microarray analysis; subdivided into ChIP-enriched genes that are up-regulated in Cacnb1−/− (left-hand column) and ChIP-enriched genes that are down-regulated in Cacnb1−/− (right hand column). Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201403021/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ronald Gregg and Dr. Weichun Lin for developing and providing the Cacnb1−/− mice; Dr. Jeff Chou, Dr. Lance Miller, and Lou Craddock from the Wake Forest Baptist Health Microarray Core Facility; and James Wood and Beth Hollbrook from the Wake Forest Baptist Health Flow Cytometry Core.

This work was supported by NIH/NIA grants R01AG15820, R01AG13934, F31AG039934, and T32AG033534; and the Translational Sciences Institute at Wake Forest Baptist Health.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- Cav

- voltage-gated calcium channel

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DM

- differentiation medium

- EC

- excitation–contraction

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GK

- guanylate kinase

- GM

- growth medium

- H&E

- hematoxylin & eosin

- LMB

- leptomycin-B

- MPC

- muscle progenitor cell

- NC

- noncanonical

- NLS

- nuclear localization sequence

- RAd

- recombinant adenoviral

- SH3

- Src homology 3

- TSS

- transcription start site

References

- Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S. 2009. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Web Server, Web Server issue):W202–W208 10.1093/nar/gkp335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguin P., Nagashima K., Gonoi T., Shibasaki T., Takahashi K., Kashima Y., Ozaki N., Geering K., Iwanaga T., Seino S. 2001. Regulation of Ca2+ channel expression at the cell surface by the small G-protein kir/Gem. Nature. 411:701–706 10.1038/35079621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguin P., Mahalakshmi R.N., Nagashima K., Cher D.H., Ikeda H., Yamada Y., Seino Y., Hunziker W. 2006. Nuclear sequestration of beta-subunits by Rad and Rem is controlled by 14-3-3 and calmodulin and reveals a novel mechanism for Ca2+ channel regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 355:34–46 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes C.A., Bergstrom D.A., Penn B.H., Seaver K.J., Knoepfler P.S., Tapscott S.J. 2004. Pbx marks genes for activation by MyoD indicating a role for a homeodomain protein in establishing myogenic potential. Mol. Cell. 14:465–477 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00260-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D., Cornet V., Geib S., Carlier E., Volsen S., Hoshi T., Mori Y., De Waard M. 2000. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the beta subunit. Neuron. 25:177–190 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80881-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaud I., Monteil A., Nargeot J., Lory P. 2006. Properties and role of voltage-dependent calcium channels during mouse skeletal muscle differentiation. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 27:75–81 10.1007/s10974-006-9058-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D., Von Kuster G., Coraor N., Ananda G., Lazarus R., Mangan M., Nekrutenko A., Taylor J. 2010. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 19:Unit 19.10 1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z., Yang J. 2010. The ß subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 90:1461–1506 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalucci D., Zhang D.H., DeSantiago J., Aimond F., Barbara G., Chemin J., Bonci D., Picht E., Rusconi F., Dalton N.D., et al. 2009. Akt regulates L-type Ca2+ channel activity by modulating Cavalpha1 protein stability. J. Cell Biol. 184:923–933 10.1083/jcb.200805063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari N. 1992. A single nucleotide deletion in the skeletal muscle-specific calcium channel transcript of muscular dysgenesis (mdg) mice. J. Biol. Chem. 267:25636–25639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T.C., Hanley T.A., Mudd J., Merlie J.P., Olson E.N. 1992. Mapping of myogenin transcription during embryogenesis using transgenes linked to the myogenin control region. J. Cell Biol. 119:1649–1656 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyavskaya Y., Ebert A.M., Milligan E., Garrity D.M. 2012. Voltage-gated calcium channel CACNB2 (β2.1) protein is required in the heart for control of cell proliferation and heart tube integrity. Dev. Dyn. 241:648–662 10.1002/dvdy.23746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colecraft H.M., Alseikhan B., Takahashi S.X., Chaudhuri D., Mittman S., Yegnasubramanian V., Alvania R.S., Johns D.C., Marbán E., Yue D.T. 2002. Novel functional properties of Ca(2+) channel beta subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J. Physiol. 541:435–452 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis B.M., Catterall W.A. 1984. Purification of the calcium antagonist receptor of the voltage-sensitive calcium channel from skeletal muscle transverse tubules. Biochemistry. 23:2113–2118 10.1021/bi00305a001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert A.M., McAnelly C.A., Srinivasan A., Linker J.L., Horne W.A., Garrity D.M. 2008. Ca2+ channel-independent requirement for MAGUK family CACNB4 genes in initiation of zebrafish epiboly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:198–203 10.1073/pnas.0707948105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D.G., Cheng T.C., Cserjesi P., Chakraborty T., Olson E.N. 1992. Analysis of the myogenin promoter reveals an indirect pathway for positive autoregulation mediated by the muscle-specific enhancer factor MEF-2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3665–3677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J., Lemke H., Baisch H., Wacker H.H., Schwab U., Stein H. 1984. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J. Immunol. 133:1710–1715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J., Nekrutenko A., Taylor J.; Galaxy Team. 2010. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11:R86 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Miranda-Laferte E., Neely A., Hidalgo P. 2007. The Src homology 3 domain of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels promotes endocytosis via dynamin interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 282:2156–2162 10.1074/jbc.M609071200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg R.G., Messing A., Strube C., Beurg M., Moss R., Behan M., Sukhareva M., Haynes S., Powell J.A., Coronado R., Powers P.A. 1996. Absence of the beta subunit (cchb1) of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor alters expression of the alpha 1 subunit and eliminates excitation-contraction coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:13961–13966 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin C.A., Apponi L.H., Long K.K., Pavlath G.K. 2010. Chemokine expression and control of muscle cell migration during myogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 123:3052–3060 10.1242/jcs.066241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter C.E., Abiria S.A., Dzhura I., Wu Y., Ham A.J., Mohler P.J., Anderson M.E., Colbran R.J. 2006. L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation mediated by phosphorylation of the beta subunit by CaMKII. Mol. Cell. 23:641–650 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., Bailey T.L., Noble W.S. 2007. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 8:R24 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H., Pironkova R., Onwumere O., Rousset M., Charnet P., Hudspeth A.J., Lesage F. 2003. Direct interaction with a nuclear protein and regulation of gene silencing by a variant of the Ca2+-channel beta 4 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:307–312 10.1073/pnas.0136791100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks G.R., Raikhel N.V. 1995. Protein import into the nucleus: an integrated view. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:155–188 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo P., Neely A. 2007. Multiplicity of protein interactions and functions of the voltage-gated calcium channel beta-subunit. Cell Calcium. 42:389–396 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitt M., Bett A., Prevec L., Graham F. 1998. Construction and propagation of human adenovirus vectors. Cell Biology. Celis J.E., editor Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1500–1512 [Google Scholar]

- Hohaus A., Person V., Behlke J., Schaper J., Morano I., Haase H. 2002. The carboxyl-terminal region of ahnak provides a link between cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels and the actin-based cytoskeleton. FASEB J. 16:1205–1216 10.1096/fj.01-0855com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden N.S., Tacon C.E. 2011. Principles and problems of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 63:7–14 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4:44–57 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D. 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12:996–1006 10.1101/gr.229102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S., Wakamori M., Miki T., Uriu Y., Nonaka M., Bito H., Beedle A.M., Mori E., Hara Y., De Waard M., et al. 2007. RIM1 confers sustained activity and neurotransmitter vesicle anchoring to presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Nat. Neurosci. 10:691–701 10.1038/nn1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson C.M., Chaudhari N., Sharp A.H., Powell J.A., Beam K.G., Campbell K.P. 1989. Specific absence of the alpha 1 subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor in mice with muscular dysgenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1345–1348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan P.F., Chun H., Keleş S. 2008. CMARRT: a tool for the analysis of ChIP-chip data from tiling arrays by incorporating the correlation structure. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2008:515–526 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda A.E., Kim H.S., Ruth P., Perez-Reyes E., Flockerzi V., Hofmann F., Birnbaumer L., Brown A.M. 1991. Normalization of current kinetics by interaction between the alpha 1 and beta subunits of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel. Nature. 352:527–530 10.1038/352527a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 227:680–685 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand F., Auda-Boucher G., Levitsky D., Rouaud T., Fontaine-Pérus J., Gardahaut M.F. 2004. Endothelial cells within embryonic skeletal muscles: a potential source of myogenic progenitors. Exp. Cell Res. 301:232–241 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung A.T., Imagawa T., Campbell K.P. 1987. Structural characterization of the 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel from rabbit skeletal muscle. Evidence for two distinct high molecular weight subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 262:7943–7946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuranguer V., Papadopoulos S., Beam K.G. 2006. Organization of calcium channel beta1a subunits in triad junctions in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 281:3521–3527 10.1074/jbc.M509566200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyris J.P., Gondeau C., Charnet A., Delattre C., Rousset M., Cens T., Charnet P. 2009. RGK GTPase-dependent CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel inhibition is independent of CaVbeta-subunit-induced current potentiation. FASEB J. 23:2627–2638 10.1096/fj.08-122135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.C., Zha X.H., Faralli H., Yin H., Louis-Jeune C., Perdiguero E., Pranckeviciene E., Muñoz-Cànoves P., Rudnicki M.A., Brand M., et al. 2012. Comparative expression profiling identifies differential roles for Myogenin and p38α MAPK signaling in myogenesis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:386–397 10.1093/jmcb/mjs045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Laferte E., Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Schmidt S., Zeug A., Ponimaskin E.G., Neely A., Hidalgo P. 2011. Homodimerization of the Src homology 3 domain of the calcium channel β-subunit drives dynamin-dependent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 286:22203–22210 10.1074/jbc.M110.201871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes M.B., Christensen R.G., Wakabayashi A., Stormo G.D., Brodsky M.H., Wolfe S.A. 2008. Analysis of homeodomain specificities allows the family-wide prediction of preferred recognition sites. Cell. 133:1277–1289 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontell M., Ontell M.P., Buckingham M. 1995. Muscle-specific gene expression during myogenesis in the mouse. Microsc. Res. Tech. 30:354–365 10.1002/jemt.1070300503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai A.C. 1965. Developmental genetics of a lethal mutation, muscular dysgenesis (Mdg), in the mouse. II. Developmental analysis. Dev. Biol. 11:93–109 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90039-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinçon-Raymond M., Vicart P., Bois P., Chassande O., Romey G., Varadi G., Li Z.L., Lazdunski M., Rieger F., Paulin D. 1991. Conditional immortalization of normal and dysgenic mouse muscle cells by the SV40 large T antigen under the vimentin promoter control. Dev. Biol. 148:517–528 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90270-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platzer A.C. 1978. The ultrastructure of normal myogenesis in the limb of the mouse. Anat. Rec. 190:639–657 10.1002/ar.1091900303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando T.A., Blau H.M. 1994. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J. Cell Biol. 125:1275–1287 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schredelseker J., Di Biase V., Obermair G.J., Felder E.T., Flucher B.E., Franzini-Armstrong C., Grabner M. 2005. The beta 1a subunit is essential for the assembly of dihydropyridine-receptor arrays in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:17219–17224 10.1073/pnas.0508710102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schredelseker J., Dayal A., Schwerte T., Franzini-Armstrong C., Grabner M. 2009. Proper restoration of excitation-contraction coupling in the dihydropyridine receptor beta1-null zebrafish relaxed is an exclusive function of the beta1a subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 284:1242–1251 10.1074/jbc.M807767200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]