Abstract

Objective

To compare length of gestation following ART as calculated by three methods from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System (SART CORS) and vital records (birth and fetal death) in the Massachusetts Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal Data System (PELL).

Design

Historical cohort study

Setting

Database linkage analysis

Patients

Live or stillborn deliveries

Interventions

None

Main Outcome Measures

ART deliveries were linked to live birth or fetal death certificates. Length of gestation in 7,171 deliveries from fresh, autologous ART cycles (2004–2008) was calculated and compared to that of SART CORS using methods: M1=(Outcome Date − Cycle Start Date); M2=((Outcome date − Transfer Date)+17 Days); and M3=((Outcome Date − Transfer Date) + (14 Days + Day of Transfer)). Generalized estimating equation models were used to compare methods.

Results

Singleton and multiple deliveries were included. Overall prematurity (delivery <37 weeks) varied by method of calculation: M1=29.1%, M2=25.6%, M3=25.2%, and PELL=27.2%. ART methods, M1–3, varied from those of PELL by at least 3 days in over 45% of deliveries and by over a week in more than 22% of deliveries. Each method differed from every other (p < .001 across each comparison.)

Conclusions

Estimates of preterm birth in ART vary depending on source of data and method of calculation. Some estimates may overestimate preterm birth rates for ART conceptions.

Keywords: Gestational Age, ART, SART CORS, PELL, prematurity

Introduction

There has been considerable recent interest in exploring the health outcomes of ART pregnancies. It is well known that the greatest health risk in ART is that of multiple birth with its concomitant increase in prematurity and low birthweight babies (1–3). More recent data suggest that even among singleton outcomes, prematurity and low birthweight are increased (4, 5). For example, Schieve et al. in 2002, demonstrated that ART singletons born at >37 weeks gestation had a 2.6 fold risk of low birthweight as compared to national norms (5). The 2006 national ART surveillance data showed a 14.3% rate of prematurity in singleton ART deliveries (6) as compared to national rates of 10.5%(7).

Prematurity, birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation, relies on accurate calculation of gestational age. Despite its importance, it is well known that gestational age is not a fixed measurement (8, 9). In clinical practice, standard calculation of gestational age for most pregnancies relies on either the difference between the date of delivery and date of last menstrual period (LMP) or on clinical estimates. Though delivery date is known with some certainty, date of LMP is often less clearly known. Women may forget the LMP date, incorrectly determine the first date of their menstrual flow, have irregular menses, or simply not be willing to report this information to their obstetricians. Mid cycle or early pregnancy spotting may further complicate these estimates. Gestational age estimates are also complicated by individual differences in the follicular phase which can vary by as much as 14 days (10). Calculations of gestational age based on LMP have more recently been replaced or augmented by estimates based on early obstetrical ultrasound dating or postnatal assessments of maturity, although these also can lead to inaccurate results (8, 11). The question of which of the above methods best estimates gestational age has been the subject of longstanding debate. In contrast to spontaneously conceived pregnancies, it is possible to accurately estimate gestational age in ART pregnancies based directly on the date of fertilization (12).

The uncertainty in gestational age calculation is of particular concern in comparing rates of prematurity in ART deliveries to those of the general population. ART cycles have a cycle start date but are generally uncoupled from the actual start of the menstrual cycle and thus methods that rely on LMP cannot be used. Thus, while gestational age for ART may be more accurately calculated using fertilization date, when compared to the general population, the methods could potentially yield different rates of prematurity based simply on the method of calculation.

Methods for calculating gestational age have not often been compared directly. In the current study we had the unique opportunity to obtain gestational age estimates recorded on the live birth and fetal death certificates of babies delivered following ART in MA. We compared the gestational age in these vital records to that computed from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System (SART CORS) national ART database calculated by three different methods using cycle information available in the SART CORS database for ART births. The methods chosen had either been used previously for publications on gestational age in ART births that were directly compared with spontaneous pregnancy or they were presumed to be of value in helping to elucidate the source of information present on the birth certificate. Dates of retrieval and transfer relate directly to date of fertilization and these are available only for ART births. Our underlying hypothesis was that methods from SART CORS would yield gestational age values that differed from those of the birth certificates. The goal, therefore, was to compare length of gestation and rates of prematurity when calculations were done using each of the methods and thereby understand whether any of these calculations yield values consistent with those calculated from the birth certificate.

Materials and Methods

Data were obtained from two sources 1) the SART CORS online database, a system that contains cycle-based ART data from the majority of US ART clinics and 2) the birth certificates and fetal death records in the Massachusetts based Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal (PELL) data system, an ongoing population-based project that compiles data from statewide vital statistics systems. SART CORS data are collected by SART and reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in compliance with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (13). SART maintains HIPAA compliant business associates agreements with reporting clinics. The PELL system links records from live birth and fetal death certificates, hospital discharges of mothers and infants, and program data on early intervention and other State programs (14). The study took place under a Memorandum of Understanding executed between SART and the three entities that participate in the PELL project, Boston University, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human subjects approval was obtained from all entities and participating Universities. The project is known as the MA Outcome Study of Assisted Reproductive Technology, or MOSART. The study was approved by the SART Research Committee.

ART cycles with start dates between 2004 and 2008 and either patient zip code or treatment clinic located in MA were obtained from SART. SART CORS data for 10,138 ART cycles resulting in delivery between July 1 2004 and Dec 31 2008 were deterministically linked to PELL birth certificates using mother’s first and last name, mother’s date of birth, father’s name, and date of infant delivery. Methods for linkage have been described previously (15, 16). We linked 9,092 deliveries for a linkage rate of 89.7% overall and 95.0% for deliveries in which both mother’s zip code and clinic were located in MA. Gestational age from the PELL birth certificate was primarily calculated as the delivery date minus the date of LMP that was recorded on the live birth or fetal death certificate. LMP is recorded on these certificates by delivery room staff on the basis of information present in the clinical chart. When LMP is not available or improbable (11), the gestational age is estimated from early clinical obstetrical ultrasound dating or early postnatal assessments of maturity. Information on the birth/fetal death certificates indicated that this alternative estimation was used in 2.6% of deliveries. No information was available about whether or not the delivery room staff and the obstetrician had access to ART treatment records or knowledge of the fact that ART was used.

Estimates of gestational age from SART CORS were calculated using three methods. Method 1 used SART CORS outcome date minus the date of cycle start. This method was used so that we could assess how closely gestational age based on cycle start corresponded with the gestational age calculated from information on the birth certificate. Method 2 used the SART CORS outcome date minus the date of transfer and was calculated by taking this difference and adding 17 days. This method, that assumed a day 3 transfer and a 14 day follicular phase, was used for many years by SART as the automatic method of calculating gestational age in deidentified data released for research studies (personal communication). Method 3 used SART CORS outcome date minus date of transfer but then added 14 days plus the cycle day of transfer (ranging from 1–7 days). This calculation is equivalent to the outcome date minus the date of retrieval (or fertilization) plus 14 days. We used date of transfer in M2 and M3 rather than retrieval date to ultimately make the method applicable to calculating gestational age in frozen embryo transfer cycles where retrieval date is unavailable in the dataset.

We compared gestational age estimates of the 7,171 fresh, autologous deliveries from the 9,092 linked deliveries (SART CORS treatment data linked to vital records). Deliveries were limited to those with >20 weeks gestation as calculated by all of the methods and included both singleton and multiple deliveries. Differences in prematurity across the 4 methods of gestational age computation per delivery were tested using logistic regression for correlated binary data via generalized estimating equations (GEE) (17) and considered significantly different at P<0.05.

Results

The study population of 7,171 women who delivered the ART pregnancies was 86.3% non-Hispanic-White and ranged in age from 20 to 45 years old (mean 35 +/− 4 years). There were 5,173 singleton, 1,915 twin and 83 higher order multiple pregnancies. All deliveries were from fresh autologous cycles.

The rate of prematurity as calculated by each method is shown in Table 1. Rates of prematurity differed by calculation method resulting in up to 2% difference. Though small, the difference between methods was highly significant (P<0.0001).

Table 1.

| Gestational Age (weeks) | SART Method 1 (Outcome − Cycle Start) (%) | SART Method 2 (Outcome − Date of Transfer) + 17 Days) (%) | SART Method 3 (Outcome − Cycle Start)+ 14 Days + Day of Transfer***) (%) | PELL Live Birth/death Certificate (Delivery − LMP) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤28 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| 29–32 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| 33–36 | 22.1 | 19.2 | 18.8 | 20.4 |

| 37–41 | 70.5 | 73.9 | 74.3 | 71.0 |

| >41 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.7 |

| Prematurity (<37 Weeks) | 29.1 | 25.6 | 25.2 | 27.2 |

ART births include 7,171 singleton, twins, and high order multiples

p < 0.001 for each method as compared to every other method via generalized estimating equations (GEE).

Equivalent to using (Outcome Date − Day of Fertilization) + 14 days

Table 2 shows the discrepancy in gestational age between each of the methods from SART CORS and the vital records. Gestational age calculated by SART Method 1 (using cycle start date) differed from the calculation on the live birth/fetal death certificate by at least 1 day in 90.5% of deliveries. Using day of transfer by either Method 2 or 3, there was a discrepancy of at least one day in over 79% of deliveries. Relevant to Method 3, the percentage of transfers on < 3 days, day 3, day 4, day 5 and >day 5 were 3.2%, 84.3%, 0.5%, 11.8% and 0.2% respectively. A difference of at least 8 days, and in some cases over 2 weeks was found in more than 23% of deliveries using Method 2 or 3.

Table 2.

Discrepancy in Estimates of Length of Gestation Among ART Births Between SART Methods and Vital Records*

| Discrepancy (days) | SART Method 1 vs. PELL BC/FD (%) | SART Method 2 vs. PELL BC/FD (%) | SART Method 3 vs. PELL BC/FD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 days | 9.5 | 18.9 | 20.8 |

| 1–2 days | 30.7 | 32.3 | 30.6 |

| 3–4 days | 22.1 | 15.2 | 15.1 |

| 5–7 days | 12.9 | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| 8+ days | 24.8 | 23.9 | 23.9 |

ART births include 7,171 singleton, twins, and high order multiples

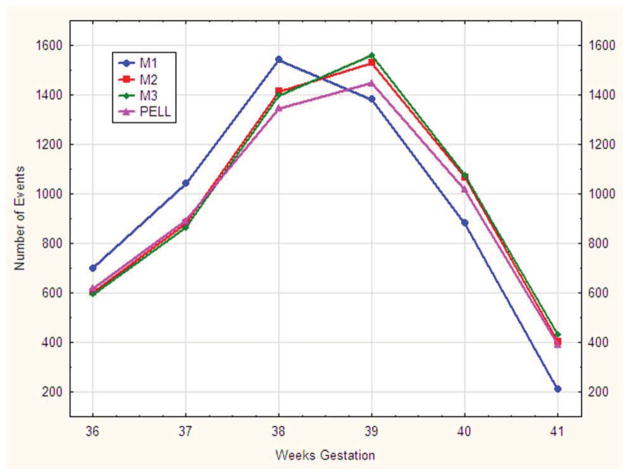

A more nuanced depiction of the four methods is shown in Figure 1 as the number of deliveries at each week, by week of gestation, for each of the four methods from 36 weeks through 41 weeks gestation. The distribution of births using Method 1 (using cycle start date) is shifted to the left compared with the other methods. Live birth and fetal death certificates estimated fewer term deliveries at 38, 39 and 40 weeks than SART Methods 2 and 3 (which used date of transfer). Methods 2 and 3 differ from each other only slightly, but significantly as they do so consistently with all the differences shifting the distribution to the right.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Live Births + Fetal Deaths by Four Methods of Calculating Gestational Age. Three methods of calculating gestational age from the national Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology database (M1, M2, M3) were compared with gestational age calculated from the Pregnancy to Early Live Longitudinal (PELL) system birth/fetal death certificate data.

Discussion

Studies have shown that ART pregnancies have an increased risk for preterm and very preterm delivery compared to the general population (3, 4, 6, 18). Prematurity has been shown to be increased even in singleton ART deliveries (6, 18). While it is likely that this observation will be supported by additional studies, and while many factors may be related to its expression, it is important to realize that gestational age itself is a flexible measure that is prone to error. Unlike birthweight, which can be measured by placing the baby on a scale, gestational age is a calculated measure the accuracy of which can vary. Gestational age depends on both the data recorded (for example LMP on the birth certificate) and the algorithm used to perform the calculation. When gestational age is calculated by one method for one population (e.g., ART deliveries) and another method for a comparison population (e.g., deliveries in the general population), the calculation itself can introduce error into the relative estimate of prematurity. The current study demonstrates that estimates of gestational age can vary significantly as a result of the method used for their calculation. By comparing four different methods of calculation of gestational age for the same deliveries, we have shown that alternative methods resulted in differences in as much as 3.9 percentage points in their estimate of prematurity. The data suggest that when different methods are used for comparison of subsets of a single population, the possibility exists for these differences to bias the results.

It is well known that gestational age is difficult to calculate and that estimates of gestational age are prone to error (12). Many factors contribute to this problem. Although gestational age is, in theory, most correctly estimated from the date of fertilization, in a spontaneous pregnancy this date is unknown. Instead of using date of fertilization, we have historically relied on LMP, the clearest evidence of the start of the cycle in which conception occurred and the easiest point from which to base a calculation. Unfortunately, LMP is often either unknown, irregular, or reported inaccurately. Even when LMP is correctly reported, the variability in the length of the follicular phase can introduce bias. The follicular phase, which averages 16.5 days in length, can vary from 9 to 23 days (10). As a result, the gestational age of spontaneous pregnancies can vary by as much as 14 days even when LMP is known with certainty.

In ART pregnancies, date of fertilization (or presumptive fertilization date in a frozen embryo transfer cycle) is from 2 to 7 days prior to the day of embryo transfer. Using this information, gestational age can be objectively calculated. The accurate calculation of gestational age in ART is often then compared with the inaccurate estimate for the spontaneous pregnancy. The discrepancy can mean that two very different measures are being compared. There may also be some misclassification of gestational age and/or birthweight even within the national ART data as shown previously (19). Differences between outcomes in ART deliveries and those of the general population are small in magnitude and studies of ART outcome therefore often rely on large population databases. Many of these studies are also retrospective. In the U.S., studies of ART outcome have utilized the SART CORS database or the CDC National ART Surveillance System (NASS) database and are often compared with National Vital Statistics data. The large numbers make it possible to better document small differences between populations. As shown by our results, methodological differences may be one underlying cause.

M3 is theoretically the best method for calculating gestational age because it uses both date of transfer and day of transfer, effectively calculating gestational age on the basis of date of fertilization. Beydoun proposed that this method be used as a standard and that estimates of birthweight for gestational age be recalibrated using ART deliveries (12). When calculated by this method ART deliveries had lowest prematurity rate (25.2%).

An interesting feature of the current study is that a difference in length of gestation by at least one day occurred more than 75% of the time when gestational age, calculated by any method from SART CORS, was compared to the matched information on the birth certificates. The calculation using cycle start date differed the most, making clear that cycle start date was not being entered on the birth certificate as the assumed LMP. However, estimates from the date of fertilization (M3) and the date of transfer (M2) also differed in over 75% of cases, and by as much as a week or more in 20% of cases. This raises the curious question of exactly what method is being used to enter the LMP on the birth certificate for ART deliveries. The estimate does not utilize ultrasound dating or postnatal assessments of maturity, since these were relied on in only the 2.6% of the birth certificates where LMP was missing or improbable. Our data suggest the need for further exploration of how LMP is recorded on birth certificates for ART pregnancies. This is particularly important as a recent study by Zhang et al (20) has shown that many ART pregnancies are not recorded as such on the birth certificate and it is therefore likely that the obstetrical staff do not routinely know when pregnancies were initiated by ART.

Until quite recently (2012), all datasets released by SART calculated the gestational age by a single method, date of outcome minus date of transfer plus 17 days, the method we call M2 (personal communication). This calculation was adequate when most transfers occurred on day 3, but the change to day 5 transfer in a substantial proportion of cycles makes this calculation inadequate for current use. Prior comparisons of gestational age according to day of transfer (21) and use of fresh versus frozen transfer (22) where percentage of day 3 and 5 transfer can differ, could have included some measure of error introduced by this issue. More recently released datasets used the M3 method of calculation to report gestational age (19).

There is no simple solution to developing a method by which national SART CORS data on gestational age can be compared with national vital records data. The best method to accomplish this is to use linked data, as we did in this study, and therefore present data calculated using the same methodology for all estimates. The cost and complication of such an endeavor would make it prohibitive for most studies, however. An alternate solution might be for SART and CDC to begin collecting gestational age estimates from birth certificates when these are available for data entry. Nevertheless, since many outcomes are reported by patients themselves, a significant portion of these would be missing. A better method might be to add a field for estimated gestational age at the time of the early obstetrical ultrasound used to assess clinical intrauterine gestation (8). This estimate could be used, along with the outcome date, to calculate gestational age in a method that would mirror newer methods that may soon replace LMP based methods for calculating gestational age in spontaneous pregnancies.

This study has several limitations. One limitation is the possibility of an imperfect linkage between PELL records and SART CORS deliveries. Given the multifaceted nature of the linkage process, however, it is highly unlikely that linkages are misclassified. Dates of cycle start, retrieval, and transfer used to calculate M1–3 could also be incorrect leading to inaccuracies in the calculated values, however these parameters are entered directly by the clinic from information easily available to them and are therefore likely among the most valid of SART CORS fields. Dates of outcomes in SART CORS can also be inaccurate and we have previously shown this to be the case in approximately 5% of cycles (23). In addition, M3, the most accurate method for gestational age estimation, can only be accurately calculated for fresh cycles, since day of transfer is known in these but not in frozen cycles. Finally, this paper is limited to deliveries in MA and there could be differences between the way information is recorded in this state and in the rest of the country.

In summary, we have shown that differences of length of gestation calculations can result in different estimates of prematurity. The method for calculating gestational age, therefore, could in turn change the reported rates of prematurity and small for gestational age babies. While these differences will likely not invalidate findings that the rate of prematurity is higher in ART pregnancies than in the general population, they may influence our estimates of the extent of that issue. Observation that the calculation of gestational age is fluid and can vary according to method should be listed as a limitation in all studies of ART outcomes particularly when compared to those of non-ART deliveries. Further, our third method of gestational age calculation (M3) should be used for all future studies using the SART CORS database.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank additional MOSART team members for analytic and programming contributions: Mark Hornstein, MD, Marlene Anderka, PhD, Bruce Cohen, PhD, Dmitry Kissin, PhD, Candice Belanoff, ScD, Daksha Gopal, Lan Hoang, Donna Richard, Katrina Plummer.

SART thanks all of its members for providing clinical information to the SART CORS database for use by patients and researchers. Without the efforts of SART members, this research would not have been possible.

This work was supported by R01 HD064595-01. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Armour KL, Callister LC. Prevention of triplets and higher order multiples: trends in reproductive medicine. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19:103–11. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulet SL, Schieve LA, Nannini A, Ferre C, Devine O, Cohen B, et al. Perinatal outcomes of twin births conceived using assisted reproduction technology: a population-based study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1941–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Rebar RW, Tasca RJ. Infertility, assisted reproductive technology, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;109:967–77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000259316.04136.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perri T, Chen R, Yoeli R, Merlob P, Orvieto R, Shalev Y, et al. Are singleton assisted reproductive technology pregnancies at risk of prematurity? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2001;18:245–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1016614217411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schieve LA, Meikle SF, Ferre C, Peterson HB, Jeng G, Wilcox LS. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. [see comment] N Engl J Med. 2002;346:731–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunderam S, Chang J, Flowers L, Kulkarni A, Sentelle G, Jeng G, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance--United States, 2006. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ, et al. Births: final data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2011;60:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Petersen DJ, Hulsey TC, Mor J. Discordance between LMP-based and clinically estimated gestational age: implications for research, programs, and policy. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:395–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin C, Hsia J, Berg CJ. Variation between last-menstrual-period and clinical estimates of gestational age in vital records. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:646–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fehring R, Schneider M, Raviele K. Variability in the phases of the menstrual cycle. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nursing. 2006;35:376–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GR, de Caunes F, Hulsey TC, Tompkins ME, Allen M. Validity of postnatal assessments of gestational age: a comparison of the method of Ballard et al. and early ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:891–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91357-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beydoun H, Ugwu B, Oehninger S. Assisted reproduction for the validation of gestational age assessment methods. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992. In: 42 USC 102–493, 1992.

- 14.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tomashek KM, Kotelchuck M, Barfield W, Nannini A, Weiss J, et al. Effect of late-preterm birth and maternal medical conditions on newborn morbidity risk. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e223–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Declercq E, Belanoff C, Diop H, Gopal D, Hornstein MD, Kotelchuck M, et al. Identifying women with indicators of subfertility in a statewide population database:Operationalizing the missing link in ART research. Fertility & Sterility. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.028. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotelchuck M, Hoang L, Stern JE, Diop H, Belanoff C, Declercq E. The MOSART database: Linking the SART CORS clinical database to the population-based Massachusetts PELL reproductive public health data system. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1465-4. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luke B, Brown MB, Grainger DA, Stern JE, Klein NA, Cedars MI. The effect of early fetal losses on singleton assisted-conception pregnancy outcomes. Fertility & Sterility. 2009;91:2578–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callaghan WM, Schieve LA, Dietz PM. Gestational age estimates from singleton births conceived using assisted reproductive technology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21 (Suppl 2):79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Macaluso M, Cohen B, Schieve L, Nannini A, Chen M, et al. Accuracy of assisted reproductive technology information on the Massachusetts birth certificate, 1997–2000. Fertility & Sterility. 2010;94:1657–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT, Coutifaris C. Extended embryo culture and an increased risk of preterm delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;120:69–75. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825b88fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Coutifaris C, Molinaro T, Barnhart KT. Ovarian stimulation and low birth weight in newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011;118:863–71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822be65f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luke B, Cabral H, Cohen BB, Loang L, Plummer K, Kotelchuck M. Comparison of measures in SART database and Massachusetts vital statistics. Fertility & Sterility. 2012;98:S260. [Google Scholar]