Abstract

Background

Predisaster risk factors are related to postdisaster psychopathology even at relatively low levels of disaster exposure. A history of panic attacks (PA) may convey risk for postdisaster psychopathology and has been linked to a wide range of psychiatric disorders in Western and non-Western samples. The present study examined the main and interactive effects of pretyphoon PA and level of typhoon exposure in the onset of posttyphoon posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression (MDD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in a Vietnamese sample of typhoon survivors.

Methods

Typhoon Xangsane interrupted a Vietnamese epidemiological mental health needs assessment, providing a rare opportunity for preand posttyphoon assessments. Hierarchical logistic regression analyses evaluated whether the main and interactive effects of typhoon exposure severity and PA history were significantly related to posttyphoon diagnoses, above and beyond age, health status, pretyphoon psychiatric screening results, and history of potentially traumatic events.

Results

PA history moderated the relationship between severity of typhoon exposure and posttyphoon PTSD and MDD, but not GAD. Specifically, greater degree of exposure to the typhoon was significantly related to increased likelihood of postdisaster PTSD and MDD among individuals without a history of PA, above and beyond variance accounted for by pretyphoon psychiatric screening results. Individuals with a history of PA evidenced greater risk for postdisaster PTSD and MDD regardless of severity of typhoon exposure.

Conclusions

Preexisting PA may affect the nature of the relationship between disaster characteristics and prevalence of postdisaster PTSD and MDD within Vietnamese samples.

Keywords: anxiety/anxiety disorders, depression, GAD/generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks/agoraphobia, PTSD/posttraumatic stress disorder, stress, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Natural disasters are a significant public health concern because they affect the well being of a substantial number of individuals simultaneously; indeed, exposure has been related to risk for anxiety disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and mood disorders.[1–6] Therefore, it is important to understand what factors predict the onset of psychiatric disorders following exposure to disasters. Dose–response theory posits that as the magnitude of life stress increases, the likelihood of developing various forms of illness, as well as the severity of such illness, increases.[7] This theory has been applied in the traumatic stress literature, with consistent relationships being found between degree of trauma exposure (e.g. degree of personal threat, injury severity, duration of event, degree of acute life disruption) and subsequent onset or severity of psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD[8, 9] and depressive disorders.[10, 11] The degree of exposure to disasters is generally related to postdisaster psychiatric functioning, with greater disaster exposure being related to increased odds of postdisaster psychopathology.[1, 12] However, it is clear that trauma “dose” does not account for a majority of variance in posttrauma functioning.[8] For example, some individuals who experience relatively low levels of disaster exposure will meet criteria for new psychiatric disorders following exposure. Preexisting vulnerability factors, in addition to disaster-specific characteristics, are clearly important for identifying at-risk individuals in the wake of a disaster.

A history of panic attacks (PA) is one such preexisting vulnerability factor likely to be relevant to predicting postdisaster psychopathology. Prospective studies have found that PAs are a risk marker for a broad range of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorders,[13,14] major depressive disorder (MDD),[13–16] substance use disorders,16 and psychotic disorders.[17] Furthermore, existing theory and research conducted among trauma survivors from Cambodia indicate that PAs and PTSD may potentiate one another, presumably through activation of fear networks. For example, it has been documented that the reexperiencing symptoms of PTSD can trigger PAs in such populations.[18] It is also possible that PAs are related to increased likelihood of psychopathology following an extreme stressor due to shared familial liability,[19] increased emotional and physiological fear responding during a traumatic event (i.e. a causal relationship), or a combination of the two. However, epidemiological investigations of PA and posttrauma psychopathology in non-Western populations are lacking. With regard to disaster exposure, PAs experienced during a disaster (i.e. peri-traumatic PAs) appear to be related to short term (e.g. one year postdisaster), but not necessarily long term, psychiatric diagnoses;[20–22] however, disaster studies examining panic-relevant risk have not explicitly examined the role of preexisting PAs.

To our knowledge, no studies have examined in a single model the relationships among a predisaster PA history, degree of disaster exposure, and postdisaster psychopathology. Additionally, there is limited disaster research available from non-Western samples.[5] Past studies have found relationships between PAs and psychopathology, particularly PTSD, in nondisaster, trauma-exposed Southeast Asian samples;[23, 24] however, our understanding of the role of PA history in relation the postdisaster context is lacking.

The current study takes advantage of unique data collected from a sample of individuals living in Da Nang, Vietnam who were exposed to Typhoon Xangsane in 2006. Typhoon Xangsane, equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane, was responsible for at least 72 deaths, hundreds of severe injuries, hundreds of millions of dollars in damages to Vietnam, and was responsible for leaving several hundred thousand Vietnamese homeless.[25, 26] A mental health needs assessment was being conducted in Vietnam through the Da Nang Department of Health and the Khanh Hoa Health Service when the typhoon hit, interrupting data collection, but allowing for an unplanned prepost disaster study. As is rarely the case in disaster studies due to the unpredictable nature of disasters, the current study has the benefit of inclusion of pretyphoon psychiatric data, allowing us to better control for preexisting psychopathology than is typically the case. Finally, the data collection team was able to respond to the disaster very quickly, with a second wave of data collection occurring only a couple of months after the typhoon struck, allowing for ideal assessment of typhoon-related constructs.

The aim of the current study was to examine the main and interactive effects of pretyphoon PA history and degree of typhoon exposure in the onset of posttyphoon PTSD, MDD, and GAD, above and beyond the variance accounted for by psychiatric functioning assessed pretyphoon and history of potentially traumatic events (PTE). It was hypothesized that: (1) the main effects of severity of typhoon exposure and PA history would be related to increased odds of typhoon-related PTSD, MDD, and GAD; and (2) above and beyond the main effects, PA history would moderate the relationship between severity of typhoon exposure and posttyphoon PTSD, MDD, and GAD, such that individuals with a PA history would display elevated risk for psychopathology even at relatively low levels of exposure.

METHOD

Full methodological details are provided elsewhere.[27] In brief, in 2006, the Da Nang Department of Health and the Khanh Hoa Health Service, in cooperation with several nongovernment organizations (NGOs) were conducting a mental health needs assessment using the World Health Organization’s (WHO) brief screener. The initial data collection (Wave 1) occurred between August and October of 2006, with Typhoon Xangsane striking Da Nang province on October 26th. NGO study personnel consulted with the Disaster Research Education and Mentoring Center (DREM), in organizing Wave 2 (occurring between January 8 and January 15, 2007), a reassessment via clinical interview of approximately 800 participants who had been screened prior to the typhoon. All measures were peer-reviewed by both Vietnamese experts and consultants in the United States prior to administration; however, due to the short timeframe, no back-translation of the interview was possible.

For Wave 1, Vietnamese lay interviewers from Da Nang and Khanh Hoa received 6 days of training plus 1 day to review the measures prior to administration in the field. Surveys were completed within each household with interviews lasting approximately 2 hr each. For Wave 2, lay interviewers and physician interviewers conducted assessments and received the same training as the interviewers in Wave 1. Rates of all DSM-IV diagnoses were consistent between interviewer types.[28] The present investigation utilizes the posttyphoon (Wave 2) clinical interview diagnoses, as well as pretyphoon self-report data (Wave 1).

SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS

Wave 1 participants were recruited through a four-stage cluster sampling strategy,[27] with random selection of 30 communes per province, three hamlets per commune, and 30 households per hamlet occurring. Household members ages 11 and older were offered participation. When Typhoon Xangsane hit Da Nang province, Wave 1 had been completed in 21 of the 30 communes. A subsample of Wave 1 adults from Da Nang was surveyed again posttyphoon (Wave 2). All Wave 1 participants aged 18 and over from Da Nang were pooled in a sample frame, and persons were randomly selected via computer, resulting in the selection of an average of 38 persons at each commune with a potential 20 substitutes per commune being generated in case participants could not be reached. These procedures yielded a total of 798 completed interviews, with full data available for 762 participants. Wave 2 participants were significantly older than those completing only Wave 1 [mean age (SD) = 41.7 years (16.5) and 34.8 years (18.6), respectively; t = −9.87, P < .001]. Wave 1 and 2 participants did not significantly differ with regard to sex distribution (% women = 52.4 and 56.0%, respectively).

VARIABLES

Demographic Variables (Wave 1)

Standard demographic variables were assessed (i.e. sex, marital status, occupational status, age).

General Health Status (Wave 1)

Item #1 of the WHO, Short Form-36 (SF-36, Version 2) was administered to assess individuals’ overall health status.[29, 30] Specifically, individuals were asked, “In general, would you say your health is ‘Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair, or Poor’,” and consistent with past work,[27] responses were dichotomized as 1 = Good Health (“excellent,” “very good,” or “good”) versus 2 = Poor Health (“fair” or “poor”).

Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20 (Wave 1)

The SRQ-20 is a 20-item self-report screening measure developed by the WHO to assess the likelihood of an individual meeting criteria for any psychiatric disorder.[31] Respondents mark items dichotomously to indicate the presence or absence of symptoms over a 30-day recall period. Items include symptoms related to somatic (e.g. “Do you often have headaches?”); cognitive (e.g. “Do you have trouble thinking clearly?”), and emotional symptoms (e.g. “Do you feel nervous, tense, or worried?”) relevant to a range of psychiatric conditions. Results are reported as “case” or “noncase” (i.e. positive versus negative screen); however, the contribution of individual items to a positive screen may be suggestive of a particular category of mental disorder. Based on recommendations in the literature[32, 33] and by the WHO,[31] a cut-off of 7/8 (i.e. 7 = probable negative screen; 8 = probable positive screen) was utilized. The SRQ-20 has been found to be reliable and valid in Vietnamese populations,[34] and high internal reliability was found in the present sample (Chronbach’s α = .87).

PTSD (Wave 2)

Posttyphoon PTSD was assessed via the National Women’s Study PTSD module (NWS-PTSD),[35] a widely used measure in population-based epidemiological research originally modified from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. The NWS-PTSD has demonstrated concurrent validity and several forms of reliability (e.g. temporal stability, internal consistency, and diagnostic reliability)[36, 37] and was validated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), PTSD Field Trial against a well-established structured diagnostic interview administered by trained mental health professionals (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCID-IV[38]). We defined PTSD based on DSM-IV symptom requirements (i.e. 3 avoidance, 1 intrusion, and 2 arousal symptoms), including functional impairment. Past research in Southeast Asian populations has supported the use of a PTSD diagnosis based on DSM-IV criteria.[39] Among individuals endorsing traumatic event exposure, Cronbach’s α was .86.

MDD (Wave 2)

Posttyphoon MDD was measured using a modified version of the SCID-IV[38] that targets MDD criteria using yes/no response formats for each DSM-IV symptom. Following DSM-IV criteria, respondents met criteria for MDD if they had five or more depressive symptoms for at least 2 weeks. Support for internal consistency and convergent validity exist for this measure.[37] Cronbach’s α for this sample for individuals screening into the module was .82.

GAD (Wave 2)

Posttyphoon GAD was also measured using a modified version of the SCID-IV,[38] with items corresponding directly to DSM-IV criteria for GAD using yes/no response options. A positive diagnosis of GAD required excessive and poorly controlled anxiety and worry occurring more days than not “since the typhoon,” as well as three of six hallmark GAD symptoms, including restlessness, fatigue, concentration problems, irritability, tension, and sleep disturbance. This scale showed good internal consistency in the current sample among individuals screening into the module (Cronbach’s α = .85).

PA History (Wave 2)

Pretyphoon PAs were measured posttyphoon using a modified version of the SCID-IV[38] that included yes/no questions corresponding directly to DSM-IV criteria. Participants were designated as having a pretyphoon PA history if: (1) they endorsed four or more DSM-IV PA symptoms occurring within a single panic episode, and (2) the age at the Wave 1 assessment was greater than the age of onset of the PAs. A dichotomous variable was created (0 = no pretyphoon PA history, 1 = pretyphoon PA history). Participants (n = 44) endorsing PA onset post-Wave 1 were coded as having no history of pretyphoon PAs.

PTE Exposure (Wave 2)

Participants were asked if they had been exposed to (1) a natural disaster (other than the current typhoon), (2) a serious motor vehicle accident, (3) a weapon attack, (4) an attack without a weapon, (5) military combat or a war zone, and (6) sexual exploitation/violence. All lifetime events were assessed for Criterion A2, and a dichotomous variable of at least one previous Criterion A PTE versus no previous Criterion A PTE exposures was created.

Typhoon Exposure (Wave 2)

As reported in our prior research with hurricanes,[6, 26, 40] typhoon exposure was measured as a sum of yes–no responses (possible range = 0–7) to the following questions: (1) “Did you evacuate from the place you were living because of the storm?” (2) “Whether you evacuated or not, were you personally present when Typhoon-force winds or major flooding occurred?” (3) “Did the storm damage the place you were living or other personal property?” (4) “Because of the typhoon damage, were you unable to live in your home?” (5) “Whether you evacuated or not, how afraid were you during the typhoon that you might be killed or seriously injured during the storm?” (assessed on a 4-point scale and dichotomized as 0 = little to no threat of injury, 1 = moderate to severe threat of injury to be consistent with past work[27] and to avoid giving additional weight to one item in a 7-item scale comprised of dichotomous items) (6) “Were you injured during or after the storm?” and (7) “Was any member of your family injured or killed during or after the storm?”

DATA ANALYTIC PLAN

Analyses were conducted in PASW Statistics 18.0. First, bivariate relations were evaluated between the predictor and criterion variables using χ2 analyses. Second, a series of hierarchical logistic regression analyses was conducted to evaluate whether the main and interactive effects of typhoon exposure severity and PA history (yes/no) were significantly related to typhoon-related diagnoses of PTSD, MDD, and GAD. The covariates of PTE history (yes/no), pretyphoon psychiatric screening results (i.e. SRQ-20 caseness; yes/no), age, and health status were entered into step one of the regression equations, given that these factors have evidenced significant bivariate relationships with posttyphoon diagnoses in this sample. Conversely, other factors such as religious affiliation, sex, and marital status were not included due to a lack of significance in past investigations with this sample.[27] The main effects of typhoon exposure severity (mean centered) and PA history were entered at step two. The interaction term (product of main effects) was entered at step three. The criterion variables were diagnoses of posttyphoon PTSD, MDD, and GAD. The forms of significant interactions were subsequently examined both graphically[41] and statistically[42] to examine the significance of the relationship between the predictor (i.e. typhoon exposure) and outcome variables at both values of the moderator (i.e. PA history) above and beyond the covariates.

RESULTS

See Table 1 for sample characteristics. Individuals with, compared to without, a history of one or more PTEs were more likely to endorse a history of PAs (20.5 versus 4.1%, respectively; χ2 = 50.56, P < .001). As shown in Table 2, severity of typhoon exposure was categorized as low (severity score of 0–2), moderate (score of 3–4), or high (score of 5–7) for presentation of descriptive data in order to facilitate interpretation (i.e. categories were not utilized in the primary analyses). Pretyphoon PA history was significantly related to PTSD (χ2 = 41.73, P < .001), MDD (χ2 = 71.91, P < .001), and GAD (χ2 = 10.50, P = .001) diagnoses at the bivariate level. Severity of typhoon exposure also was significantly related to PTSD (χ2 = 20.81, P < .001), MDD (χ2 = 58.37, P < .001), and GAD (χ2 = 8.56, P < .05) diagnoses.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 762)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or% |

|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 55.9 |

| Age (years) | 41.2 (16.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 18.9 |

| Married | 70.1 |

| Divorced/separated | 2.8 |

| Widowed | 8.3 |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed/unable to work | 3.0 |

| Retired | 13.9 |

| Works in the home | 8.8 |

| Student | 4.2 |

| Employed | 70.1 |

| General health status (% “poor health”) | 71.3 |

| Criterion A traumatic event history (% positive) | 45.1 |

| Natural disaster (other than current typhoon) | 23.5 |

| Serious motor vehicle accident | 18.5 |

| Attacked with a weapon | 6.7 |

| Attacked (no weapon) | 4.1 |

| Combat or war zone exposure | 21.8 |

| Sexual exploitation/violence | 10.1 |

| Pretyphoon panic attack history (% positive) | 18.1 |

| Pretyphoon SRQ-20 Screen (% positive) | 19.5 |

| Posttyphoon psychiatric diagnosesa | |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2.5 |

| Major depression | 5.9 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.2 |

| Panic disorder | 9.3 |

1.7% of the sample met criteria for comorbid PTSD and MDD posttyphoon.

TABLE 2.

Pretyphoon panic attack history and typhoon exposure severity in relation to rates of typhoon-related PTSD, major depression, and GAD

| Variable | % (n) PTSD |

% (n) Major depression |

% (n) GAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panic attack history | |||

| Negative (81.9%) | 0.9 (6) | 2.8 (17) | 1.4 (9) |

| Positive (18.1%) | 10.7 (14) | 24.0 (25) | 5.8 (8) |

| Typhoon exposure | |||

| Low (32.5%) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (2) | 0.4 (1) |

| Moderate (48.2%) | 2.4 (9) | 4.3 (15) | 2.4 (9) |

| High (19.2%) | 7.4 (11) | 20.3 (25) | 4.7 (7) |

| Total sample | 2.6 (20) | 5.9 (42) | 2.2 (17) |

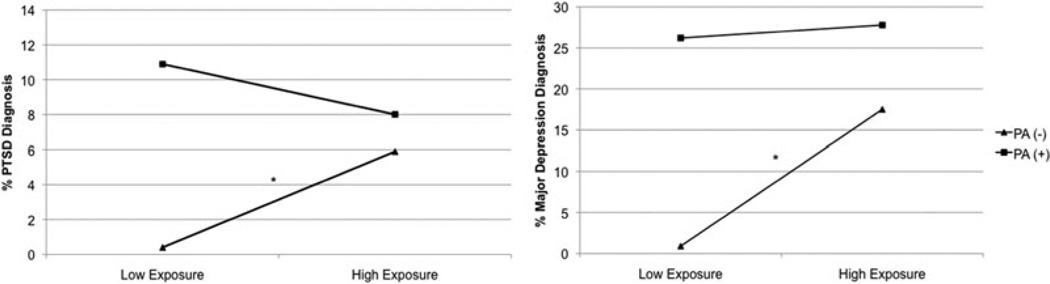

A positive PTE history and pretyphoon SRQ-20 caseness were significantly related to increased odds of meeting criteria for PTSD and MDD (see Table 3). The main effects of typhoon exposure severity and pretyphoon PA history significantly predicted PTSD and MDD diagnoses, with greater levels of typhoon exposure and a history of PAs being related to increased odds of diagnoses. The interaction term significantly predicted PTSD and MDD diagnoses above and beyond the main effects and covariates. Examination of the interactions indicated that: (a) the relationship between severity of typhoon exposure and PTSD was significant only among individuals without (OR = 2.51, 95% CI = 1.33–4.71, β = .92, P < .01) compared to with (OR = .70, 95% CI = .44–1.74, β = –.13, P = .70) a PA history, and (b) the relationship between severity of typhoon exposure and MDD also was significant only among individuals without (OR = 4.03, 95% CI = 2.37–6.84, β = 1.39, P < .001) compared to with (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = .77–2.88, β = .40, p = .24) a PA history (see Fig. 1).1 For GAD, pretyphoon SRQ-20 caseness and greater severity of typhoon exposure were the only variables in the model related to increased likelihood of a GAD diagnosis.

TABLE 3.

Logistic regression results: prediction of typhoon-related PTSD, major depression, and GAD

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | β | Wald coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | .99 | .95–1.02 | −.02 | .86 |

| General health status | 1.08 | .30–3.89 | .08 | .02 |

| PTE history | 5.29* | 1.43–19.65 | 1.67 | 6.20 |

| Pretyphoon SRQ-20 caseness | 3.80* | 1.22–10.83 | 1.34 | 6.23 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Typhoon exposure | 1.64* | 1.06–2.55 | .49 | 4.82 |

| Pretyphoon panic attack history | 5.38** | 1.85–15.71 | 1.68 | 9.50 |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Interaction term | .36* | .14–.88 | −1.04 | 5.05 |

| Major depression | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | 1.01 | .99–1.03 | .01 | 1.01 |

| General health status | 2.67 | .97–7.37 | .98 | 3.57 |

| PTE history | 3.26** | 1.45–7.36 | 1.18 | 8.13 |

| Pretyphoon SRQ-20 caseness | 2.26* | 1.12–4.59 | .82 | 5.12 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Typhoon exposure | 2.57*** | 1.79–3.70 | .95 | 26.24 |

| Pretyphoon panic attack history | 6.35*** | 2.80–14.40 | 1.85 | 19.53 |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Interaction term | .31** | .14–.67 | −1.18 | 8.91 |

| GAD | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | .99–1.05 | .02 | 1.21 |

| General health status | 4.81 | .58–39.90 | 1.57 | 2.12 |

| PTE history | 1.33 | .41–4.31 | .28 | .22 |

| Pretyphoon SRQ-20 caseness | 3.31* | 1.16–9.44 | 1.20 | 5.02 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Typhoon exposure | 1.66* | 1.07–2.58 | .51 | 5.11 |

| Pretyphoon panic attack history | 1.91 | .60–6.10 | .65 | 1.18 |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Interaction term | .97 | .36–2.70 | −.02 | .00 |

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001.

Figure 1.

Pretyphoon panic attack history moderating the relationship between typhoon exposure severity and PTSD/major depression diagnoses.

Note: Low and high exposure = 1 SD below and above the mean on typhoon exposure severity; * = significant slope based on statistical probing analyses.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the role of pretyphoon PA history and severity of typhoon exposure in the development of posttyphoon PTSD, MDD, and GAD in a representative sample of Vietnamese typhoon survivors. Consistent with hypotheses, higher levels of typhoon exposure and a history of PAs were associated with increased odds of posttyphoon diagnoses of PTSD and MDD, above and beyond age, health status, PTE history, and Wave 1 psychiatric screening. Greater typhoon exposure, but not PA history, was associated with increased odds of posttyphoon GAD.

Enhancing the previously established link between severity of disaster exposure to increased likelihood for postdisaster psychiatric disorders, the novel contribution of the current study is in sampling survivors from a non-Western community and in the availability of pretyphoon psychiatric screening data. The previously displayed relationships between PAs and a variety of types of psychopathology[43] were replicated in this study among Vietnamese typhoon survivors, although limited to posttyphoon PTSD and MDD, but not GAD.

Above and beyond the main effects, PA history moderated the relationship between severity of typhoon exposure and posttyphoon PTSD and MDD, but not GAD. Specifically, degree of typhoon exposure was significantly related to postdisaster PTSD and MDD among individuals without a history of PAs. However, the relationship between severity of exposure and posttyphoon PTSD and MDD was not significant among those with a history of PAs. Individuals with a history of PAs may be more sensitive to the impact of any level of trauma on subsequent psychiatric functioning. This finding is consistent with the available, albeit limited, laboratory data indicating that panic reactivity is related to decreased tolerance to subsequent stressors.[44] Replication of the findings is needed to draw firm conclusions about the nature of the observed relationships.

Assessment of PA history may aid in the identification of those at increased risk for postdisaster psychopathology, as well as provide a potential opportunity for the development of early intervention programs. For example, a brief interoceptive exposure intervention postdisaster to decrease reactivity to symptoms of arousal (e.g. Anxiety Sensitivity Amelioration Training[45]) may be beneficial for those with a PA history. Existing literature provides some evidence for the efficacy of behavioral interventions on postdisaster distress,[46] as well as psychological first aid.[47] Conversely, individuals without preexisting psychiatric vulnerabilities who are potentially high-risk may be best identified by external factors (e.g. degree of disaster exposure). The current findings also may provide ancillary support for the utility of investigating combined treatments among individuals from Southeast Asia who suffer from cooccurring PTSD and PAs, such as that reported by Hinton et al.[48] It is possible that addressing PAs and anxiety sensitivity (i.e. fear of anxiety and related sensations[49]) explicitly in such treatments could be beneficial for preventing relapse of PTSD and related conditions, as well as facilitating primary PTSD treatment efforts.

The study has a number of limitations, many stemming from the deviations from its original design as a needs assessment survey, which did not include a thorough psychiatric assessment. First, the temporal relationships among PTE history, pretyphoon PAs, pretyphoon psychiatric diagnoses, and posttyphoon functioning cannot be definitively determined given the study design. For example, pretyphoon PA history was assessed posttyphoon (i.e. at Wave 2). It is possible that individuals experiencing greater levels of distress following the typhoon were more likely to endorse a lifetime history of PAs, or that pretyphoon PAs reflect greater rates of pretyphoon psychiatric diagnoses; therefore replication utilizing prospective assessment for all key variables is needed. Second, measures were not validated in Vietnamese populations specifically. Third, a new set of interviewers was added to the second wave of data collection. Although no differences were noted on DSM-IV diagnoses, interviewer effects may be present. Fourth, all data relied on participants’ self-report. Fifth, the current study did not assess individual differences in anxiety sensitivity, a well-established vulnerability factor for panic-spectrum psychopathology and PTSD in Western and Southeast Asian populations,[50–52] which limits our ability to conclude that a history of PAs rather than anxiety sensitivity accounted for the observed effects. In addition, the SRQ-20 screens for past 30-day psychiatric symptoms (lifetime data are not available), and diagnostic data on lifetime psychiatric diagnoses were not obtained at Wave 1 (only Wave 2). Similarly, a number of community and family variables may be important to consider in future investigations of disaster responding.[5] Taken together, there are a number of important pretyphoon characteristics that were not adequately assessed in the current investigation and should be considered in alternate explanations of the present findings. Sixth, participants in Wave 2 of the study were significantly older than those only participating in Wave 1. It is unclear whether this has an effect on the current findings, but one could question the generalizability of the Wave 2 sample to the original full sample. Finally, there is evidence indicating that culture-specific manifestations of panic exist (e.g. “orthostatic PAs” – dizziness experienced as a result of standing up from sitting or lying down).[53] Therefore, future studies in non-Western samples, particularly disaster-exposed samples that have not been targeted in past investigations of orthostatic panic, would benefit from a broader, culturally informed assessment.

CONCLUSION

The present study documented a moderating role of predisaster PAs in the relationship between severity of disaster exposure and postdisaster PTSD and MDD in a representative sample of Vietnamese typhoon survivors. Further study regarding the nature of this relationship may aid in surveillance efforts and development of tailored interventions for individuals vulnerable to postdisaster psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from Atlantic Philanthropies to the Community Health Centers of Da Nang and Khanh Hoa, Vietnam, with personnel and technical support from the Veterans for America Foundation. Special thanks to Anne Seymour for her assistance in coordinating international efforts of the research team.

Contract grant sponsor: Atlantic Philanthropies.

Footnotes

Note that examination of Fig. 1 reveals that for those with a history of panic attacks, the frequency of PTSD diagnosis is slightly higher among those with lower, compared to higher, levels of typhoon exposure; however, statistical probing indicated that this difference is not statistically significant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meewisse M, Olff M, Kleber R, et al. The course of mental health disorders after a disaster: predictors and comorbidity. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:405–413. doi: 10.1002/jts.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cukor J, Wyka K, Jayasinghe N, et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in utility workers deployed to the World Trade Center following the attacks of September 11, 2001. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28:210–217. doi: 10.1002/da.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan F, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among adolescents following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:44–53. doi: 10.1002/jts.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thavichachart N, Tangwongchai S, Worakul P, et al. Post-traumatic mental health establishment of the Tsunami survivors in Thailand. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;3:5–11. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, et al. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part 1 an empirical review of the empirical literature 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part II summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002;65:240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyler AR, Masuda M, Holmes TH. Magnitude of life events and seriousness of illness. Psychosom Med. 1971;33:115–122. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197103000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaysen D, Rosen G, Bowman M, et al. Duration of exposure and the dose-response model of PTSD. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:63–74. doi: 10.1177/0886260508329131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollica RF, McInnes K, Pham T, et al. The dose-effect relationships between torture and psychiatric symptoms in Vietnamese ex-political detainees and a comparison group. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:543–553. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih RA, Schell TL, Hambarsoomian K, et al. Prevalence of PTSD and major depression following trauma-center hospital-ization. J Trauma. 2010;69:1560–1566. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e59c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence, characteristics, and long-term sequelae of natural disaster exposure in the general population. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:661–679. doi: 10.1023/A:1007814301369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinley DJ, Walker JR, Enns MW, et al. Panic attacks as a risk for later psychopathology: results from a nationally representative survey. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28:412–419. doi: 10.1002/da.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed V, Wittchen H. DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: How specific are panic attacks? J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, et al. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:618–626. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baillie AJ, Rapee RM. Panic attacks as risk markers for mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:240–244. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0892-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin RD, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early anxious/withdrawn behaviours predict later internalising disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:874–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pitman RK, et al. The panic attack-posttraumatic stress disorder model: applicability to orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugees. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37:101–116. doi: 10.1080/16506070801969062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chantarujikapong SI, Scherrer JF, Xian H, et al. A twin study of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, panic disorder symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder in men. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams RE, Boscarino JA. A structural equation model of perievent panic and posttraumatic stress disorder after a community disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:61–69. doi: 10.1002/jts.20603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams RE, Boscarino JA. Perievent panic attack and depression after the world trade center disaster: a structural equation model analysis. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2011;13:69–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Person C, Tracy M, Galea S. Risk factors for depression after a disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:659–666. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235758.24586.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinton D, Hinton S, Pham T, et al. ‘Hit by the wind’ and temperature-shift panic among Vietnamese refugees. Transcult Psychiatry. 2003;40:342–376. doi: 10.1177/13634615030403003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinton DE, Pollack MH, Pich V, et al. Orthostatically induced panic attacks among Cambodian refugees: flashbacks, catastrophic cognitions, and associated psychopathology. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12:301–311. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhry P, Ruysschaert G. Climate change and human development in Vietnam. Hum Dev Report. 2007;46:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iglesias G Asian Disaster Preparedness Center. Safer cities. Bangkok: Asian Disaster Preparedness Center; 2006. Promoting safer housing construction through CBDRM: Community-designed safe housing in post-Xangsane Da Nang City. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amstadter AB, Acierno R, Richardson LK, et al. Posttyphoon prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder in a Vietnamese sample. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:180–188. doi: 10.1002/jts.20404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amstadter AB, Richardson L, Acierno R, et al. Does interviewer status matter? An examination of lay interviewers and medical doctor interviewers in an epidemiological study in Vietnam. Int Persp Victimol. 2010;5:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Galea S, et al. Psychological sequelae of the 2004 Florida hurricanes: implications for post-disaster intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:S103–S108. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A User’s Guide to the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) Geneva: World Health Organization; [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuan T, Harpham T, Huong N. Validity and reliability of the self-reporting questionnaire 20 items (SRQ-20) in Vietnam. Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2004;14:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harpham T, Reichenbaum M, Oser R, et al. Measuring mental health in a cost-effective manner. Health Policy Planning. 2003;18:344–349. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giang KB. Self-Reported Illness, Mental Distress and Alcohol Problems in a Rural District in Vietnam. Stockholm: The Department of Health Sciences, Karolinska Instituet; 2006. Assessing Health Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilpatrick D, Resnick H, Saunders B, et al. The National Women’s Study PTSD Module. Charleston, SC: National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina; 1989. pp. 358–364. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, et al. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and co-morbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer RL, Williams J, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, et al. Assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder in Cambodian refugees using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: psychometric properties and symptom severity. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:405–409. doi: 10.1002/jts.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick D, et al. Risk and protective factors for psychopathology among older versus younger adults after the 2004 Florida hurricanes. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221327.97904.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen J, Cohen P. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. Applied Multivariate Regression for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinley DJ, Walker JR, Enns MW, et al. Panic attacks as a risk for later psychopathology: results from a nationally representative survey. Depression Anxiety. 2011;28:412–419. doi: 10.1002/da.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall EC, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, et al. Panic reactivity to voluntary hyperventilation challenge predicts distress tolerance to bodily sensations among daily cigarette smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:313–321. doi: 10.1037/a0012752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K, et al. Anxiety Sensitivity Amelioration Training (ASAT): a longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:302–319. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basoglu M, Salcioglu E, Livanou M, et al. Single-session behavioral treatment of earthquake-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized waiting list controlled trial. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:1–11. doi: 10.1002/jts.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson J, et al. A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:537–552. doi: 10.1002/jts.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: a cross-over design. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:617–629. doi: 10.1002/jts.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:938–946. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olatunji BO, Wolitzky-Taylor KB. Anxiety sensitivity and the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:974–999. doi: 10.1037/a0017428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, et al. Neck-focused panic attacks among Cambodian refugees: a logistic and linear regression analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:119–138. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hinton DE, Pham T, Tran M, et al. CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:429–433. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048956.03529.fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hinton DE, Hinton L, Tran M, et al. Orthostatic panic attacks among Vietnamese refugees. Transcult Psychiatry. 2007;44:515–544. doi: 10.1177/1363461507081640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]