Abstract

Rhythmic oscillations within the 3-12 Hz theta frequency band manifest in the rodent hippocampus during a variety of behaviors and are particularly well characterized during spatial navigation. In contrast, previous studies of rhythmic hippocampal activity in primates under comparable behavioral conditions suggest it may be less apparent and possibly less prevalent, or even absent, compared to the rodent. We compared the relative presence of low frequency oscillations in rats and humans during spatial navigation by employing an oscillation detection algorithm (“P-episode” or “BOSC”) to better characterize their presence in microelectrode local field potential (LFP) recordings. This method quantifies the proportion of time the LFP exceeds both a power and cycle duration threshold at each frequency, characterizing the presence of 1) oscillatory activity compared to background noise, 2) the peak frequency of oscillatory activity, and 3) the duration of oscillatory activity. Results demonstrate that both humans and rodents have hippocampal rhythmic fluctuations lasting, on average, 2.75 and 4.3 cycles, respectively. Analyses further suggest that human hippocampal rhythmicity is centered around ~3Hz while that of rats is centered around ~8Hz. These results establish that low frequency rhythms relevant to spatial navigation are present in both the rodent and human hippocampus, albeit with different properties under the behavioral conditions tested.

Keywords: rodent, human, hippocampus, delta, theta, spatial navigation

Previous studies have demonstrated the existence and functional relevance of the rodent hippocampal theta (3-12 Hz) rhythm, relating it to arousal, movement, spatial navigation, and memory (Green and Arduini, 1954; Vanderwolf, 1969; Winson, 1978). Theta amplitude correlates with movement speed (McFarland et al., 1975), abolishing the rodent theta rhythm impairs spatial memory (Winson, 1978), and hippocampal place cells systematically vary their firing relative to theta oscillations (O’Keefe and Recce, 1993) to encode spatial location (Jensen and Lisman, 2000). During movement, theta activity typically manifests in rodents as a continuous voltage fluctuation that persists until the cessation of movement (Vanderwolf, 1969). Although the exact relationship between the theta rhythm and behavior is still being delineated (Buzsaki, 2005), there is little debate that the rodent theta rhythm exists and has functional relevance to spatial memory and navigation.

In contrast, there has been only mixed evidence for hippocampal theta in nonhuman primates (Green and Arduini, 1954; Skaggs et al., 2007; Stewart and Fox, 1991). Stewart and Fox observed 7-9Hz theta activity in anesthetized monkeys along with “considerable amounts of low-frequency EEG” activity, which likely included oscillations in the delta band and lower theta band. In addition, these authors and others (Robinson, 1980) made the qualitative observation that theta activity in primates typically occurs in shorter “bouts” of activity compared to the more continuous rodent theta rhythm. Together, these difficulties in consistently identifying a continuously observable, frequency specific primate homologue to the rodent hippocampal theta rhythm have led to questions about the existence of theta oscillations in the non-human primate, and, by extension, humans altogether (Skaggs et al., 2007).

This view stands in contrast to early evidence from human hippocampal depth recordings from clinical populations that have demonstrated oscillatory activity in the 3-12 Hz range (Arnolds et al., 1980; Brazier, 1968; Halgren et al., 1978b), although the behavioral correlates and relation to rodent theta in some reports is more controversial (Halgren et al., 1978b; Robinson, 1980). Similar to rodents, human hippocampal/medial temporal lobe (MTL) low frequency oscillations have been associated with sleep (Bodizs et al., 2001; Cantero et al., 2003), spatial navigation (Cornwell et al., 2008; Ekstrom et al., 2005; Watrous et al., 2011), and memory (Lega et al., 2011). These studies have found that delta (1-4 Hz) and theta (4-8 Hz) oscillations increase during exploration, such as real (Arnolds et al., 1980) and virtual movement (Ekstrom et al., 2005; Watrous et al., 2011), and that theta coordinates the timing of hippocampal neurons (Jacobs et al., 2007) during memory encoding (Rutishauser et al., 2010). These parallels between humans and rodents suggest that theta activity may serve a similar functional role in both species.

Although there appear to be functional parallels between human and rodent low frequency hippocampal oscillations, important distinctions remain. Human intracranial (Lega et al., 2011; Mormann et al., 2008; Rutishauser et al., 2010) and magnetoencephalography (de Araujo et al., 2002) studies have identified prominent behavior-related hippocampal and medial temporal lobe activity centered at ~3Hz, lying at the interface of the canonical delta and theta frequency bands. Other studies, though, have observed changes in both delta and theta bands in the human hippocampus (Ekstrom et al., 2005; Mormann et al., 2008; Watrous et al., 2011). Together, these findings are consistent with the observation that low-frequency oscillations occur at a lower peak frequency in larger animals (Miller, 1991; Penttonen, 2003; Robinson, 1980). Another potential difference between rat and human low frequency oscillations is the qualitative observation that human oscillations often occur in short bursts (Cantero et al., 2003) rather than as a nearly continuous signal in rodents (Vanderwolf, 1969), although intracranially recorded raw traces from the hippocampus (Ekstrom et al., 2005; Watrous et al., 2011) and MTL (Watrous et al., in press) typically show oscillations lasting several cycles. Thus, previous observations indicate that there may be differences in both the frequency and duration of human low-frequency oscillations compared to rodents, though this issue has yet to be addressed systematically.

We sought to clarify this issue by comparing human hippocampal activity during virtual navigation and rodent hippocampal activity during Barnes Maze exploration. One challenge in conducting such inter-species comparisons deals with comparing real and virtual navigation. Rodent virtual navigation experiments have demonstrated hippocampal place cell activity, theta oscillations, and phase precession (Harvey et al., 2009) in the absence of vestibular motion inputs (Chen et al., 2013), supporting the idea that virtual navigation can be used as an experimental proxy for studying navigation related neural activity. Consistent with this, we have identified the behavioral correlates of the human data reported here previously (Watrous et al., 2011), finding behavior-related lowfrequency power modulations associated with changes in virtual movement speed, spatial view, and task demands

In this report, we assessed recordings of human and rodent LFP data quantitatively using a validated oscillatory detection algorithm (known as either P-episode or BOSC) (Caplan et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 2011) to better characterize and compare rodent and human theta oscillations. Briefly, this algorithm performs time-frequency decomposition using wavelets to estimate power values, regresses out the background 1/f signal, and then subjects the remaining signal for each epoch of interest to power and duration threshold criteria. Values exceeding these power criteria for a minimum duration are marked as oscillatory events and the resulting dependent measure is the proportion of recording time oscillatory events are observed (P-episode) (van Vugt et al., 2007). The method thus accounts for background noise, allowing more direct comparisons between different frequency bands, and allows direct quantification of the duration (number of cycles) of an ongoing oscillation.

We analyzed a total of 284 human hippocampal recordings from seven patients with pharmacologically intractable epilepsy, excluding data from all electrodes implanted in subsequently resected tissue. Details regarding the general recording procedures and navigation tasks used in each species have been published previously (Fedor et al., 2010; Watrous et al., 2011). The current results are novel as they are based on P-episode/BOSC. We also analyzed 30 recordings from 5 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats with implanted hippocampal CA3/CA1 bipolar fissure microelectrodes similar to our human recordings (i.e., Fried-Behnke electrodes).

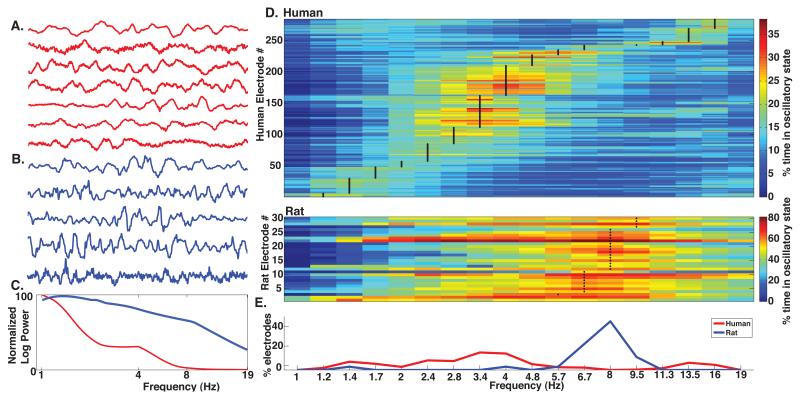

We first compared the peak frequency exhibited by human and rodent hippocampal LFPs during the spatial navigation tasks (humans, virtual navigation; rats, Barnes maze). Visual inspection of raw traces from each individual (5 rodents and 7 humans) showed rhythmic voltage fluctuations from ~3 to 8 Hz, with recordings from the human hippocampus (Fig 1A) exhibiting lower frequency oscillations compared to rodents (Fig 1B,C). We confirmed this impression by first calculating P-episode (cycle duration criteria >= 1) for each species and electrode and identified the frequency at which each electrode showed maximal activity (Fig 1D; black lines and dots indicate peak detected frequency at each electrode in humans and rodents, respectively). The largest proportion of human recordings showed maximal activity at 3.4 Hz, consistent with numerous other studies showing prominent activity at this frequency (Bodizs et al., 2001; Brazier, 1968; Huh, 1988; Jacobs et al., 2007; Lega et al., 2011; Zaveri et al., 2001). In contrast, none of the rodent recordings showed maximal activity at this frequency (Fig 1D). Instead, the largest proportion (50%) of rodent recordings showed maximal oscillatory activity at 8Hz, consistent with the notion of Type I (atropine-resistant) theta during rodent locomotor behavior (Kramis et al., 1975; Vanderwolf, 1969). None of the human recordings showed maximal activity at 8Hz, leading to a significant difference in the distribution of peak frequencies between species (Figure 1E; p < 0.001 two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). These results confirm the presence of human hippocampal theta activity and suggest that the majority of low frequency oscillatory activity in humans manifests at a lower peak frequency compared to rodents during spatial navigation.

Figure 1.

Theta is present in humans at a lower frequency compared to rodents during spatial navigation. A) Examples of human hippocampal raw LFP traces, each from a separate patient, during virtual navigation, showing prominent low frequency oscillations. B) Examples of raw LFP traces, each from a different rat, during the Barnes Maze, also showing prominent low frequency oscillations. C) Example power spectral density plots for a human electrode (red) and a rodent electrode (blue) during navigation. D) Proportion of time oscillatory activity was detected as a function of frequency for 284 human hippocampal recordings (top) and 30 rodent recordings (bottom). Black vertical lines (humans) and dots (rats) indicate the peak frequency at which oscillatory activity was detected for each recording. Note the difference in color scale for humans and rodents. E) Proportion of electrodes with peak activity at each frequency.

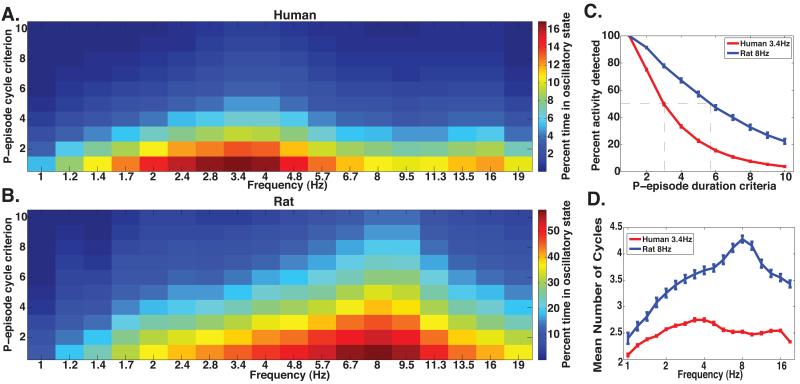

While the data demonstrates a difference in peak frequency, it is also important to assess transient vs. sustained oscillatory bouts of theta activity. To this end, we calculated P-episode for each hippocampal recording and varied the duration criteria for identifying oscillatory activity. To do this, we investigated oscillatory activity lasting from 1 to 10 cycles (as shown in Figure 2A-B, 10 cycles appeared to be the upper limit, in our data set, for detecting oscillations). Figure 2A shows the percentage of time oscillatory activity was detected at each frequency and duration criteria averaged across our human recordings. Comparing this to a similar plot derived from our rodent recordings (Fig 2B) demonstrated two quantitative species differences in LFP oscillations. First, at the 1-cycle duration criteria, significantly more oscillatory activity was detected at the rodent peak frequency of 8Hz compared to the human peak frequency of 3.4 Hz (p<0.001,Mann-Whitney test). Second, when increasing the number of cycles used in our duration cutoff, the amount of detectable oscillatory activity decreased more rapidly in human recordings compared to those of the rodent (Figure 2C). This suggests that rat low frequency oscillations lasted a greater number of cycles than human low frequency oscillations. This result is visually evident by looking at the “color spread” along the vertical axis in Figures 2A and 2B and was quantitatively evaluated in two ways. The slope of these functions across all sampled recordings was significantly more negative (steeper) in humans (Figure 2C; p<0.001, Mann-Whitney test) and the average P-episode duration criteria at which half of the maximum activity was detected was lower in humans than in rodents (p<0.001, Mann-Whitney test, 3.2 and 5.8, respectively). These findings indicate a more rapid decline in detected activity at increasing cycles criteria in humans compared to rats, suggesting that human low frequency oscillations lasted fewer numbers of cycles on average.

Figure 2.

Human theta is less continuous compared to rodent theta. A) Proportion of time each frequency was detected averaged across all 284 human recordings and at increasing Pepisode duration criteria. B) Similar to A, but for 30 rodent recordings. C) Proportion of time oscillatory activity was detected at the human peak frequency of 3.4 Hz and the rodent peak frequency of 8 Hz. Gray dashed lines correspond to the half-maximum P-episode duration criteria at the human and rodent peak frequency. D) Average number of cycles for each detected oscillatory event for humans and rodents. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean across electrodes.

To approach this same issue with a slightly different analysis, we also calculated the average number of cycles for each detected oscillatory event across electrodes using a minimal duration criteria of at least 1 cycle. Human oscillatory activity lasted significantly fewer cycles compared to rodents (Figure 2D, p<0.002 at each frequency, Mann-Whitney test). Whereas human activity lasted 2.75 cycles at the peak-detected frequency of 3.4 Hz, rodent 8Hz activity lasted 4.3 cycles. It is important to note that rodent low frequency oscillations lasted greater numbers of cycles across all frequency bands from 1-19Hz although this difference was most pronounced at the peak preferred frequencies, as shown in Figure 2D. Thus, both analyses confirmed the presence of human hippocampal low frequency oscillations at a lower peak frequency and indicate that human activity is less continuous compared to rodents.

Finally, we assessed how low-frequency activity varied during movement. In our human recordings, we calculated the percent time oscillatory activity was detected between 1-10 Hz during the top and bottom quartile of virtual movement speed (referred to as fast and slow movement, respectively). In our rat recordings, we compared the same measures during a period in which movement was restricted in the start box with active exploration of the Barnes maze. This analysis was conducted on all rodent data and a subset of the human data (n=240 electrodes) for which we had data in both conditions. In both data sets, we detected greater oscillatory activity at higher frequencies during movement compared to either slow or still periods, suggesting that movement resulted in increased oscillatory activity at higher frequencies. In humans, a 2 × 14 condition by frequency ANOVA revealed main effects of frequency and condition and a frequency by condition interaction (each F(1,6718) > 5, and all p < .001). These results are consistent with previous findings that have shown oscillatory power increases with movement speed (Ekstrom et al., 2005; Watrous et al., 2011) and qualitative observations, based on raw traces, that movement results in a frequency increase (Ekstrom et al., 2005). For the rodent data, a 2 × 14 condition by frequency ANOVA revealed main effects of frequency and condition and a frequency by condition interaction (each F(1,938) > 2.85, and all p < .001). These findings are also consistent with previous rodent studies demonstrating increases in running speed result in both increases in theta power and frequency (Czurko et al., 1999; Geisler et al., 2007; McFarland et al., 1975; Mitchell et al., 2008).

Using a novel computational method to better characterize oscillatory activity in humans and rats during spatial navigation tasks, we find that oscillations in the human hippocampus occur at a lower frequency (~3.4Hz as compared to ~8Hz) and are less continuous than rodent theta. These findings are consistent with qualitative observations suggesting such frequency (Lega et al., 2011; Miller, 1991) and continuity (Arnolds et al., 1980; Stewart and Fox, 1991) differences between rodents and primates. While previous reports have suggested such differences, no previous study has directly compared recordings between species. Although our results assessing hippocampal low-frequency activity is potentially confounded by studying patients with epilepsy, our results are consistent with previous research investigating the spectral properties of the medial temporal lobe invasively in clinical populations (Brazier, 1968; Huh, 1988; Zaveri et al., 2001) and non-invasively in healthy participants (Cornwell et al., 2008; de Araujo et al., 2002). Additionally, we only analyzed electrodes drawn from areas that did not show epileptogenic activity and thus would be more likely to be directly involved in behavior.

How might human and rodent hippocampal oscillations be interpreted given these differences? Previous analysis from our group (Watrous et al., 2011) and others (Bodizs et al., 2001; Jacobs et al., 2007; Lega et al., 2011) suggest functional parallels between human hippocampal low frequency oscillations and rodent (type I) theta. More broadly, numerous studies have shown the importance of human hippocampal activity at 3-8 Hz across a variety of behaviors (Arnolds et al., 1980; Axmacher et al., 2010; Brazier, 1968; Halgren et al., 1978a; Rutishauser et al., 2010). Within this band, the distinction between delta and theta activity is less clear, with some studies showing similar effects in these frequency bands (Jacobs et al., 2007; Watrous et al., 2011) and others functionally dissociating activity in these bands (Lega et al., 2011; Rutishauser et al., 2010). One possibility is that such distinctions only emerge during different behaviors, which could be tested by comparing human hippocampal activity in the delta and theta band across multiple hippocampally-dependent behaviors. Regardless of the resolution of these issues, our results indicate that navigation-related human hippocampal oscillations peak, in terms of prevalence, at or near 3Hz, at least during a spatial navigation task similar to that used in rodents. This activity impinges on the classical boundaries of delta and theta and questions the utility of defining activity based upon these boundaries.

We also observed differences in the duration of oscillatory activity, in terms of number of detected cycles, between species. Oscillations in both species, however, lasted roughly comparable amounts of total time. Human oscillations at 3.4 Hz had a period of ~290ms and lasted an average of 2.75 cycles for a total duration of ~800ms while rodent oscillations at 8Hz had a period of 125ms and lasted an average of 4.3 cycles for a total duration of ~540ms. Although previous work suggested that the number of oscillatory cycles, rather than total duration, is the critical factor in determining the computational capacity of a given rhythm (discussed in Van Vugt et al, 2007), our results do not allow us to determine which factor (cycle length or total duration) is most behaviorally-relevant. Comparing oscillatory duration between species during correct vs. incorrect behavior may be one way to address this issue as this would provide a more direct link to successful vs. unsuccessful computational processing in the hippocampal circuit.

To our knowledge, these results provide the first direct, quantitative comparison of human and rodent hippocampal activity during spatial navigation, a hippocampally-dependent (Burgess, 2008; Mitchell et al., 2008) behavior known to elicit theta activity in each species (Ekstrom et al., 2005; Kahana et al., 1999; Watrous et al., 2011). One potential limitation with our study is that there are a number of differences between rats and humans that are difficult, if not impossible, to fully equate, including differences in body morphology, different visual and other sensory systems, different reliance on behavioral strategies (verbal vs. non-verbal), and differences in hippocampal connectivity. Of particular importance here, we tested our patients in virtual reality, due to constraints of the clinical testing environment, while rats freely explored the Barnes Maze. Theta oscillations are present in VR in rodents (Harvey et al., 2009; Terrazas et al., 2005) although direct comparisons of real and VR navigation suggest an overall reduction in power and frequency (Chen et al., 2013). Compared to the frequency differences between species reported here, the decrease in rodent peak frequency during VR was relatively small (less than 1 Hz reduction) and the decrease in the theta index, a measure of power at the peak frequency, showed only a modest reduction between conditions. These differences thus would be unlikely to account for the observed decrease in peak frequency (~5 Hz) and significantly lower cycle duration (~2.8 vs. 4.3) we observed in our human compared to rat data. Future studies will aim to compare low frequency oscillations during human real and VR navigation but based on the Chen et al. study, we expect that our results in VR would represent a lower bound for oscillatory activity detected during real navigation. In conclusion, our results help better establish the existence of low-frequency oscillations during navigation in humans, a likely analogue of type I theta in rats, and suggest important differences in how these manifest during behaviors in which they are consistently observed in rodents.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sloan Foundation, Hellman Young Investigator Award, Grant Sponsor: NINDS; Grant Number: RO1NS076856, and the Bronte Epilepsy Research Program. We thank Jeremy Caplan for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Arnolds DE, Lopes da Silva FH, Aitink JW, Kamp A, Boeijinga P. The spectral properties of hippocampal EEG related to behaviour in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;50(3-4):324–8. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(80)90160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Cohen MX, Fell J, Haupt S, Dumpelmann M, Elger CE, Schlaepfer TE, Lenartz D, Sturm V, Ranganath C. Intracranial EEG correlates of expectancy and memory formation in the human hippocampus and nucleus accumbens. Neuron. 2010;65(4):541–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodizs R, Kantor S, Szabo G, Szucs A, Eross L, Halasz P. Rhythmic hippocampal slow oscillation characterizes REM sleep in humans. Hippocampus. 2001;11(6):747–53. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier MA. Studies of the EEG activity of limbic structures in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1968;25(4):309–18. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(68)90171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N. Spatial cognition and the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:77–97. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Theta rhythm of navigation: link between path integration and landmark navigation, episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus. 2005;15(7):827–40. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantero JL, Atienza M, Stickgold R, Kahana MJ, Madsen JR, Kocsis B. Sleep-dependent theta oscillations in the human hippocampus and neocortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(34):10897–903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10897.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan JB, Madsen JR, Schulze-Bonhage A, Aschenbrenner-Scheibe R, Newman EL, Kahana MJ. Human theta oscillations related to sensorimotor integration and spatial learning. J Neurosci. 2003;23(11):4726–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04726.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, King JA, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. How vision and movement combine in the hippocampal place code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(1):378–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215834110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell BR, Johnson LL, Holroyd T, Carver FW, Grillon C. Human hippocampal and parahippocampal theta during goal-directed spatial navigation predicts performance on a virtual Morris water maze. J Neurosci. 2008;28(23):5983–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5001-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czurko A, Hirase H, Csicsvari J, Buzsaki G. Sustained activation of hippocampal pyramidal cells by ‘space clamping’ in a running wheel. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(1):344–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo DB, Baffa O, Wakai RT. Theta oscillations and human navigation: a magnetoencephalography study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(1):70–8. doi: 10.1162/089892902317205339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom AD, Caplan JB, Ho E, Shattuck K, Fried I, Kahana MJ. Human hippocampal theta activity during virtual navigation. Hippocampus. 2005;15(7):881–9. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M, Berman RF, Muizelaar JP, Lyeth BG. Hippocampal theta dysfunction after lateral fluid percussion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(9):1605–15. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler C, Robbe D, Zugaro M, Sirota A, Buzsaki G. Hippocampal place cell assemblies are speed-controlled oscillators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):8149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JD, Arduini AA. Hippocampal electrical activity in arousal. J Neurophysiol. 1954;17(6):533–57. doi: 10.1152/jn.1954.17.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, Babb TL, Crandall PH. Activity of human hippocampal formation and amygdala neurons during memory testing. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978a;45(5):585–601. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(78)90159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, Babb TL, Crandall PH. Human hippocampal formation EEG desynchronizes during attentiveness and movement. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978b;44(6):778–81. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(78)90212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Collman F, Dombeck DA, Tank DW. Intracellular dynamics of hippocampal place cells during virtual navigation. Nature. 2009;461(7266):941–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AM, Whitten TA, Caplan JB, Dickson CT. BOSC: A better oscillation detection method, extracts both sustained and transient rhythms from rat hippocampal recordings. Hippocampus. 2011;22(6):1417–28. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh K, Meador KJ, Loring DW. Spectral analysis of human hippocampal EEG: behavioral activation. J Epilepsy. 1988;1(3):151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Kahana MJ, Ekstrom AD, Fried I. Brain oscillations control timing of singleneuron activity in humans. J Neurosci. 2007;27(14):3839–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4636-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Lisman JE. Position reconstruction from an ensemble of hippocampal place cells: contribution of theta phase coding. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83(5):2602–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ, Sekuler R, Caplan JB, Kirschen M, Madsen JR. Human theta oscillations exhibit task dependence during virtual maze navigation. Nature. 1999;399(6738):781–4. doi: 10.1038/21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramis R, Vanderwolf CH, Bland BH. Two types of hippocampal rhythmical slow activity in both the rabbit and the rat: relations to behavior and effects of atropine, diethyl ether, urethane, and pentobarbital. Exp Neurol. 1975;49(1 Pt 1):58–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lega BC, Jacobs J, Kahana M. Human hippocampal theta oscillations and the formation of episodic memories. Hippocampus. 2011;22(4):748–61. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland WL, Teitelbaum H, Hedges EK. Relationship between hippocampal theta activity and running speed in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88(1):324–8. doi: 10.1037/h0076177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. Springer-Verlag; Berlin and New York: 1991. Cortico-hippocampal interplay and the representation of contexts in the brain. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DJ, McNaughton N, Flanagan D, Kirk IJ. Frontal-midline theta from the perspective of hippocampal “theta”. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86(3):156–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormann F, Osterhage H, Andrzejak RG, Weber B, Fernandez G, Fell J, Elger CE, Lehnertz K. Independent delta/theta rhythms in the human hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2008;2:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.003.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Recce ML. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3(3):317–30. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttonen M, Buzsaki G. Natural logarithmic relationship between brain oscillators. Thalamus & Related Systems. 2003:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE. Hippocampal rhythmic slow activity (RSA; theta): a critical analysis of selected studies and discussion of possible species-differences. Brain Res. 1980;203(1):69–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(80)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser U, Ross IB, Mamelak AN, Schuman EM. Human memory strength is predicted by theta-frequency phase-locking of single neurons. Nature. 2010;464(7290):903–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Permenter M, Archibeque M, Vogt J, Amaral DG, Barnes CA. EEG sharp waves and sparse ensemble unit activity in the macaque hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98(2):898–910. doi: 10.1152/jn.00401.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Fox SE. Hippocampal theta activity in monkeys. Brain Res. 1991;538(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas A, Krause M, Lipa P, Gothard KM, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Self-motion and the hippocampal spatial metric. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(35):8085–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt MK, Sederberg PB, Kahana MJ. Comparison of spectral analysis methods for characterizing brain oscillations. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162(1-2):49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26(4):407–18. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrous AJ, Fried I, Ekstrom AD. Behavioral correlates of human hippocampal delta and theta oscillations during navigation. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105(4):1747–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.00921.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrous AJ, Tandon N, Conner CR, Pieters T, Ekstrom AD. Frequency-specific network connectivity increases underlie accurate spatiotemporal memory retrieval. Nature Neuroscience. doi: 10.1038/nn.3315. in press. doi:10.1038/nn.3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winson J. Loss of hippocampal theta rhythm results in spatial memory deficit in the rat. Science. 1978;201(4351):160–3. doi: 10.1126/science.663646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaveri HP, Duckrow RB, de Lanerolle NC, Spencer SS. Distinguishing subtypes of temporal lobe epilepsy with background hippocampal activity. Epilepsia. 2001;42(6):725–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]