LETTER

The Mycobacterium abscessus group is an increasingly recognized cause of antibiotic-resistant lung infection (1–3). The efficacy of available antibiotics must be optimized. Continuous infusion of active β-lactam agents has the potential to maximize the time blood antibiotic concentrations exceed the MIC of infecting strains (T>MIC) (4, 5). We conducted a pilot study to evaluate the steady-state concentration (Css) of cefoxitin in blood.

Cefoxitin is an intravenous β-lactam antibiotic used in combination regimens for M. abscessus therapy, with recommended doses “up to 12 g/day” (6). Our standard practice has been to give 2 g twice a day (BID) to three times a day (TID) for ≥2 months (3). More-frequent intermittent dosing is often impractical, and higher doses cause toxicity (2). Of note, the breakpoint for cefoxitin “susceptibility” is ≤16 μg/ml (7), and MICs for clinical specimens are often higher. Doses required to achieve T>MIC via continuous infusion may be larger than expected.

Cefoxitin has a half-life of 40 to 60 min when given to persons with normal renal function (8), and a 2-g bolus given to healthy adults produces a mean maximum serum concentration of 244 μg/ml and a mean area under the serum concentration-time curve (0 to ∞) of 129 h · μg/ml (9). The time corresponding to a greater than “susceptible” MIC is approximately 3 h per dose. Extrapolating from pharmacokinetic data from bolus infusion in healthy volunteers, the Css average of 2 g cefoxitin given over 8 h (or 6 g over 24 h) is expected to be approximately 16 μg/ml. Css should be achieved within 5 half-lives (5 h).

We gave three female, non-cystic fibrosis M. abscessus patients aged 64 to 76 years a single 2-g dose of cefoxitin over 8 h. This was not a therapeutic trial. In order to minimize excess risk to participants, we did not increase the study dose beyond what was prescribed for treatment. Each participant had a calculated creatinine clearance ≥ 45 ml/min (Cockcroft-Gault). Blood was drawn hourly. Cefoxitin levels were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography. Individual patient data were fit to a one-compartment intravenous infusion model using the following formula: Ct = Css × (1-e−k × t), where Ct is the concentration at time t, Css is the average steady-state concentration, and k is the elimination rate constant (10). All patients gave informed consent. The study was Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved.

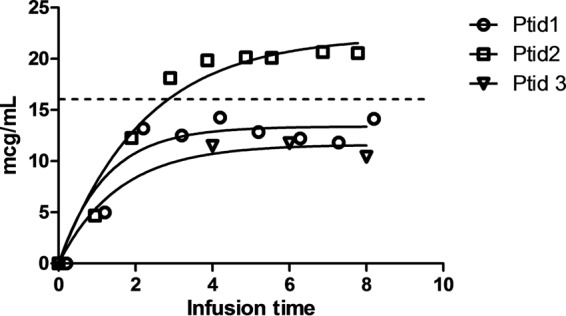

Individual patient data and cefoxitin concentration-time curves are plotted in Fig. 1. Graphically, the model fit, and curves plateaued during infusion, indicating that Css was achieved. The median Css was 13 μg/ml (range, 11 to 22 μg/ml). One patient achieved a Css > 16 μg/ml. There were no side effects related to the study dose.

FIG 1.

Serum cefoxitin concentration during an infusion of 2 g over 8 h. Individual data were fit to a one-compartment intravenous infusion model to estimate the steady-state concentration (Css) (10). Ptid1 was a 64-year-old female with estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) = 56.4 ml/min: Css, 13.37 μg/ml (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.47 to 15.28 μg/ml). Ptid2 was a 68-year-old female with CrCl = 47.0 ml/min: Css, 22.21 μg/ml (95% CI, 19.02 to 25.40 μg/ml). Ptid3 was a 79-year-old female with CrCl = 47.1 ml/min: Css, 11.27 μg/ml (95% CI, 8.80 to 13.75 μg/ml). Ptid3 completed only 4 blood draws. The dashed line at 16 μg/ml represents the MIC breakpoint for cefoxitin susceptibility (7).

For continuous infusion of cefoxitin to be effective, Css must be >MIC. MICs for isolates in this study were ≤16 μg/ml. However, the MIC for 72% of 44 isolates from other patients at our institution was ≥32 μg/ml. Our data suggest that in future studies of cefoxitin continuous infusion, the dose will need to be greater than 6 g in 24 h. Higher MICs can be targeted by increasing the dose rate proportionally to the increase in MIC (assuming linear pharmacokinetics). Higher doses may be accompanied by toxicity (2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Charles Daley and Max Salfinger reviewed the manuscript.

This work was supported by a microgrant from the National Jewish Health Department of Medicine and by the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1 TR000154).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 April 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, Jackson LA, Raebel MA, Blosky MA, de Oca RM, Shea YR, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Olivier KN. 2010. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 182:970–976. 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeon K, Kwon OJ, Lee NY, Kim B, Kook Y, Lee S, Park YK, Kim CK, Koh W. 2009. Antibiotic treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease: a retrospective analysis of 65 patients. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 180:896–902. 10.1164/rccm.200905-0704OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarand J, Levin A, Zhang L, Huitt G, Mitchell JD, Daley CD. 2011. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:565–571. 10.1093/cid/ciq237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasiakou SK, Sermaides GJ, Michalopoulos A, Soteriades ES, Falagas ME. 2005. Continuous versus intermittent administration of antibiotics: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:581–589. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70218-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JA, Webb S, Paterson D, Ho KM, Lipman J. 2009. A systematic review of clinical benefits of continuous infusion of β-lactam antibiotics. Crit. Care Med. 37:2071–2078. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a0054d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Lademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ, Winthrop K. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 175:367–416. 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CLSI. 2011. Susceptibility testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardiae, and other aerobic Actinomycetes; approved standard—second edition. CLSI document M24–A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merck & Co. Inc. 2003. Mefoxin® (cefoxitin for infusion). Package insert. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dailys/03/Jun03/060403/03p-0227-cp00001-03-exhibit-b-vol1.pdf Accessed 15 February 2014

- 9.Ko H, Cathcart KS, Griffith DL, Peter GR, Adams WJ. 1989. Pharmacokinetics of intravenously administered cefmetazole and cefoxitin and effects of probenecid on cefmetazole elimination. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:356–361. 10.1128/AAC.33.3.356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowland M, Tozer TN. 2011. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: concepts and applications, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]