Abstract

In vitro activity of the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] was inhibited by ZnCl2 with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 15 μM. Growth of Acinetobacter baumannii or Escherichia coli harboring aac(6′)-Ib in cultures containing 8 μg/ml amikacin was significantly inhibited by the addition of 2 μM Zn2+ in complex with the ionophore pyrithione (ZnPT).

TEXT

A large number of aminoglycoside-resistant isolates owe this property to the presence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (1). The aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] is responsible for resistance to amikacin (AMK) and other aminoglycosides in Acinetobacter as well as bacteria from the families of Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Vibrionaceae (1, 2). Although one way to deal with the problem of rising resistance levels is to generate new aminoglycoside variants, this path has proven to be slow and costly (3). Alternative ways include the inhibition of expression of the resistance gene using antisense strategies (4) or the identification of inhibitors of the resistance enzyme (1, 5, 6).

Zn+2 ions participate in numerous cellular processes, such as facilitating proper folding of proteins and intervening in protein interactions with macromolecules (7). Zn+2 is also required to be present in some DNA-binding proteins, such as transcription factors (7, 8). Improper binding of Zn+2 to p53 has been proposed as one cause of loss of function that leads to cancer (8). Zn+2 is also an inhibitor of several biological processes and enzymes, such as virulence of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (9), replication of coronavirus and arterivirus through inhibition of the RNA polymerase (10), deoxycholate-mediated apoptosis (11), the protease of human rhinovirus (12), the HIV reverse transcriptase (13), and an acid phosphatase (14). Here, we show that Zn+2 is also an inhibitor of AAC(6′)-Ib and, when in complex with the ionophore pyrithione, induces reduction of the level of resistance to AMK in Acinetobacter baumannii and E. coli harboring aac(6′)-Ib.

A. baumannii A155, A110, and A144 are clinical isolates that naturally carry aac(6′)-Ib (15). A. baumannii A118(pJHCMW1) and A118(pMET1) (16) were obtained by transformation of the clinical strain A118 (16) with the plasmids pJHCMW1 or pMET1, which carry aac(6′)-Ib (17, 18). E. coli TOP10(pNW1) includes the aac(6′)-Ib gene in the low-copy-number plasmid pNW1 (4). E. coli XL10-Gold(pBADMW131) (5) was used to express the enzyme for purification. Bacterial cultures were carried out in Lennox Luria (L) or Mueller-Hinton medium (19). MICs were determined by the gradient diffusion method (Etest method) with commercial strips (bioMérieux) using the procedures recommended by the supplier. Acetyltransferase activity was determined by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 412 nm when Ellman's reagent [5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB)] reacts with the coenzyme A (CoA)-SH released from acetyl-CoA after acetylation of the substrate (20), using as the source of enzyme a partially purified His-Patch containing thioredoxin-fused protein as described before with the indicated additions (5). The tested cations are those shown in Fig. 1A. Growth inhibition assays were carried out in Mueller-Hinton broth in microtiter plates with the specified additions using the BioTek Synergy 5 microplate reader. When testing the action of ZnPT, the cultures contained dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.5%. Cultures were carried out for 20 h at 37°C in 100-μl volumes with shaking, and optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured every 20 min.

FIG 1.

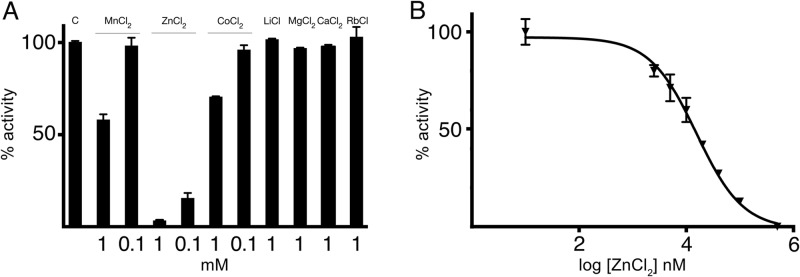

Effect of zinc on AAC(6′)-Ib activity. (A) KAN acetylating activity of AAC(6′)-Ib in the presence of different cations. Compounds were added at the indicated concentrations, and the activity was compared to that observed in the absence of additions (C). (B) The percentage of acetylating activity of KAN by AAC(6′)-Ib was calculated for reaction mixtures containing different concentrations of ZnCl2.

An initial assessment of cations as inhibitors of AAC(6′)-Ib showed that Zn+2 significantly interfered with the acetylating reaction when using kanamycin (KAN) (Fig. 1A), AMK, or tobramycin (TOB) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) as the substrates. Slight inhibition in the presence of Mn+2 or Co+2 was also noted. Next we determined the strength of inhibition using KAN as the substrate, and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was 15 μM (Fig. 1B). The ability of Zn+2 to interfere with AAC(6′)-Ib-mediated resistance to aminoglycosides in growing cells was tested using AMK, an antibiotic currently in use and generally reserved for treatment of severe infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens (21). To determine if the inhibition of AAC(6′)-Ib activity observed in vitro occurs in vivo with a concomitant reduction in levels of resistance to aminoglycosides in resistant A. baumannii, we first determined the MICs of AMK in the presence or absence of ZnCl2. Table 1 shows that there was a reduction of levels of resistance to AMK in A. baumannii A118 harboring pJHCMW1 or pMET1 when the test was done in the presence of 0.8 mM ZnCl2. Since A. baumannii is known for a high genetic variability, we extended these analyses to include the strains A155, A110, and A144, which naturally include this gene. In all cases, we observed a similar ZnCl2-induced reduction in MIC of AMK (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility levels in the presence of Zn+2

| Strain | ZnCl2 concn (mM) | ZnPT concn (μM) | MICa of AMK (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii A118(pJHCMW1) | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 4 | |

| A. baumannii A118(pMET1) | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| A. baumannii 155 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 4 | |

| 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| 0 | 10 | 0.5 | |

| A. baumannii 144 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 8 | |

| A. baumannii 110 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 2 | |

| E. coli TOP10(pNW1) | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| 0 | 2 | 8 | |

| 0 | 4 | 3 |

MICs were determined by Etest with the addition of the indicated ZnCl2 and ZnPT concentrations.

A. baumannii A155 was chosen as a model for further experiments and was used for growth curves in the presence or absence of 8 μg/ml AMK and different concentrations of ZnCl2. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2A and B, the addition of ZnCl2 to aac(6′)-Ib-harboring A. baumannii cultures resulted in inhibition of resistance to AMK. However, the ZnCl2 concentrations needed to observe a significant reduction in resistance levels were too high. We thought that the cause behind the need for such high concentrations could be that Zn+2 ions do not reach the cytoplasm at sufficient concentrations because of low permeability or the action of efflux pumps. Therefore, we tested the action of ZnPT, a coordination complex that stimulates the internalization of Zn+2 inside cells (10). MICs of AMK in the presence of 4 and 10 μM ZnPT were 3 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, suggesting more efficient uptake of zinc (Table 1). Growth curves of A. baumannii A155 cultured in the presence or absence of 8 μg/ml AMK and 2 μg/ml ZnPT showed significant inhibition of growth when the antibiotic and ZnPT were present (Fig. 2C and D). Figures 2C and D also show that ZnPT is not toxic at the concentrations used in the assay and, as expected, the addition of 2 μM ZnCl2 did not change the ability of the cells to grow in 8 μg/ml AMK. As can be seen in Fig. 2D, the cells in culture containing ZnPT start to partially recover after about 8 h of incubation. If transcription and translation continue during the initial incubation period, accumulation of enough molecules of AAC(6′)-Ib could overcome the action of the Zn+2, explaining the reinitiation of growth. Alternatively, detoxification systems could be induced or expressed at higher levels with the effect of lowering the intracellular concentration of Zn+2.

FIG 2.

Comparison of the effects of ZnCl2 and ZnPT on resistance to AMK. A. baumannii A155 (panels A to D) or E. coli(pNW1) (panels E to H) were cultured in 100 μl Mueller-Hinton broth in microtiter plates at 37°C, with the additions indicated in the figure, and the OD600 was periodically determined. Panels A, C, E, and G show the effect of addition of ZnCl2 (A and E) or ZnPT (C and G) on cell growth. Panels B, D, F, and H show the effect of addition of ZnCl2 (B and F) or ZnPT (D and H) on resistance to 8 μg/ml AMK.

As it can be observed in Fig. 2E and F, unlike the case of A. baumannii, ZnCl2 at concentrations up to 1 mM were unable to inhibit resistance to AMK in E. coli harboring aac(6′)-Ib. To test if the strong effect observed when ZnPT was added to A. baumannii cultures also occurs in the case of E. coli, we measured MIC values and performed growth curve assays in the same conditions. Table 1 shows that addition of 2 and 4 μM ZnPT results in a decrease in MIC from 16 to 8 and 3 μg/ml, respectively. Figures 2G and H show that ZnPT efficiently reverses resistance to AMK, strongly suggesting that if the zinc ions are able to reach the cytoplasm, they can exert their inhibitory activity in E. coli. Incubation in the presence of 2 μM ZnPT and absence of AMK showed that the complex has minimum, if any, toxic effect, which may be the cause of the longer lag (Fig. 2G). These results confirmed that the inhibition of growth observed in Fig. 2H must be due to the inhibition of resistance to AMK.

While the quest for inhibitors of resistance enzymes has been intensive and very successful in the case of β-lactamases (22), the same cannot be said for inhibitors of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. The efforts have been very limited, and consequently the number of identified inhibitors is small (reviewed in references 1, 2, 3, and 6). Here, we found that Zn2+, a well-known inhibitor of numerous enzymes, also inhibits the AAC(6′)-Ib-mediated acetylation of aminoglycosides. Attempts to determine the mechanism of inhibition through enzyme kinetic assays yielded inconclusive results, and its elucidation awaits further structural analyses. In the presence of ZnCl2, the MIC of AMK of A. baumannii harboring aac(6′)-Ib was reduced but only when ZnCl2 concentrations were as high as 0.5 mM, and concentrations up to 1 mM did not affect the resistance to AMK of E. coli cells carrying the gene. This could be due to reduced permeability or active efflux of the Zn+2 ions. Systems that reduce accumulation of cations in the cytoplasm have been identified in bacteria. In particular, several kinds of Zn+2 export systems have been characterized, including P-type ATPases, RND (resistance-nodulation-division) transport systems, and cation diffusion facilitators transporters (23). Proteins belonging to these families have been shown to participate in excess Zn+2 detoxification in diverse bacteria (24, 25). However, bacteria tightly regulate zinc homeostasis, and there are instances in which bacteria activate zinc uptake. One such system consisting of an ABC transporter and a negative regulator, known as Zur, has been identified in A. baumannii. This system helps counter the action of calprotectin, which protects against infection by chelating zinc and depleting the environment of free ions (26). This strong tendency to keep Zn+2 homeostasis may result in inhibition of uptake or efflux of the ions, reducing the intracellular concentration and avoiding inactivation of the enzyme. A way to overcome this limitation could be to induce an increase in the intracellular Zn2+ concentration using a zinc-ionophore complex, a strategy successfully used previously to induce inhibition of replication of coronavirus and arterivirus by zinc (10). Growth of A. baumannii and E. coli harboring aac(6′)-Ib was severely inhibited when cultured in the presence of 8 μg/ml AMK and 2 μM ZnPT, suggesting that lack of enough molecules reaching the cytosol was the reason for the failure of low concentrations of ZnCl2 to reverse the resistance phenotype. Interestingly, in the case of A. baumannii, the cells started to grow after a few hours in culture in the presence of the antibiotic and ZnPT. One possible explanation is the accumulation of enough molecules of AAC(6′)-Ib that could overcome the action of the Zn+2. Conversely, the cell could induce expression of known or unknown detoxification systems that elevate the efflux of Zn+2 ions.

Zinc is essential for human life and is required by more than 300 enzymes and 1,000 transcription factors (27). Its concentration in plasma is estimated at 12 to 16 μM, and its deficiency has been associated with serious conditions (28). Furthermore, zinc is currently used to treat a number of diseases, such as the common cold (29), diarrhea in children (30), and the genetic disorder known as Wilson's disease (31), and to treat immune defects and reduce incidence of infection and relapse in ageing people (32). The inhibition of AAC(6′)-Ib caused by zinc could result in the utilization of this element to treat resistant infections in combination with aminoglycosides.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant 2R15AI047115-04 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (to M.E.T.), a grant from CSUPERB (to M.E.T.), and a UBACyT 2011-2012 grant (to M.S.R.). D.L.L. was supported in part by a grant from Associated Students Inc., from CSUF.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 May 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00129-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. 2010. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updat. 13:151–171. 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez MS, Nikolaidis N, Tolmasky ME. 2013. Rise and dissemination of aminoglycoside resistance: the aac(6′)-Ib paradigm. Front. Microbiol. 4:121. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houghton JL, Green KD, Chen W, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2010. The future of aminoglycosides: the end or renaissance? Chembiochem 11:880–902. 10.1002/cbic.200900779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soler Bistue AJ, Martin FA, Vozza N, Ha H, Joaquin JC, Zorreguieta A, Tolmasky ME. 2009. Inhibition of aac(6′)-Ib-mediated amikacin resistance by nuclease-resistant external guide sequences in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:13230–12235. 10.1073/pnas.0906529106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin L, Tran T, Adams C, Alam JY, Herron SR, Tolmasky ME. 2013. Inhibitors of the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] identified by in-silico molecular docking. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23:5694–5698. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labby KJ, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2013. Strategies to overcome the action of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes for treating resistant bacterial infections. Future Med. Chem. 5:1285–1309. 10.4155/fmc.13.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namuswe F, Berg JM. 2012. Secondary interactions involving zinc-bound ligands: roles in structural stabilization and macromolecular interactions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 111:146–149. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loh SN. 2010. The missing zinc: p53 misfolding and cancer. Metallomics 2:442–449. 10.1039/c003915b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane JK, Byrd IW, Boedeker EC. 2011. Virulence inhibition by zinc in Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 79:1696–1705. 10.1128/IAI.01099-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. 2010. Zn(2+) inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001176. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AF, Longpre J, Loo G. 2012. Inhibition by zinc of deoxycholate-induced apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 113:650–657. 10.1002/jcb.23394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordingley MG, Register RB, Callahan PL, Garsky VM, Colonno RJ. 1989. Cleavage of small peptides in vitro by human rhinovirus 14 3C protease expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 63:5037–5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenstermacher KJ, DeStefano JJ. 2011. Mechanism of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibition by zinc: formation of a highly stable enzyme-(primer-template) complex with profoundly diminished catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286:40433–40442. 10.1074/jbc.M111.289850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox R, Thurman D. 1978. Inhibition by zinc of soluble and cell wall acid phosphatases of zinc-tolerant and non-tolerant clones of Anthoxanthum odoratum. New Phytol. 80:17–22. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1978.tb02260.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez MS, Vilacoba E, Stietz MS, Merkier AK, Jeric P, Limansky AS, Marquez C, Bello H, Catalano M, Centron D. 2013. Spreading of AbaR-type genomic islands in multidrug resistance Acinetobacter baumannii strains belonging to different clonal complexes. Curr. Microbiol. 67:9–14. 10.1007/s00284-013-0326-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramirez MS, Don M, Merkier AK, Bistue AJ, Zorreguieta A, Centron D, Tolmasky ME. 2010. Naturally competent Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolate as a convenient model for genetic studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1488–1490. 10.1128/JCM.01264-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarno R, McGillivary G, Sherratt DJ, Actis LA, Tolmasky ME. 2002. Complete nucleotide sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae multiresistance plasmid pJHCMW1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3422–3427. 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3422-3427.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soler Bistue AJ, Birshan D, Tomaras AP, Dandekar M, Tran T, Newmark J, Bui D, Gupta N, Hernandez K, Sarno R, Zorreguieta A, Actis LA, Tolmasky ME. 2008. Klebsiella pneumoniae multiresistance plasmid pMET1: similarity with the Yersinia pestis plasmid pCRY and integrative conjugative elements. PLoS One 3:e1800. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green KD, Chen W, Garneau-Tsodikova S. 2012. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of the aminoglycoside resistance acetyltransferase Eis from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ChemMedChem 7:73–77. 10.1002/cmdc.201100332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig W. 2012. Aminoglycosides, p 712–726 In Grayson ML. (ed), Kucers' the use of antibiotics. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drawz SM, Bonomo RA. 2010. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:160–201. 10.1128/CMR.00037-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hantke K. 2001. Bacterial zinc transporters and regulators. Biometals 14:239–249. 10.1023/A:1012984713391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anton A, Weltrowski A, Haney CJ, Franke S, Grass G, Rensing C, Nies DH. 2004. Characteristics of zinc transport by two bacterial cation diffusion facilitators from Ralstonia metallidurans CH34 and Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:7499–7507. 10.1128/JB.186.22.7499-7507.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grass G, Fan B, Rosen BP, Franke S, Nies DH, Rensing C. 2001. ZitB (YbgR), a member of the cation diffusion facilitator family, is an additional zinc transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:4664–4667. 10.1128/JB.183.15.4664-4667.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hood MI, Mortensen BL, Moore JL, Zhang Y, Kehl-Fie TE, Sugitani N, Chazin WJ, Caprioli RM, Skaar EP. 2012. Identification of an Acinetobacter baumannii zinc acquisition system that facilitates resistance to calprotectin-mediated zinc sequestration. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003068. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad AS. 2013. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: its impact on human health and disease. Adv. Nutr. 4:176–190. 10.3945/an.112.003210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wellinghausen N, Rink L. 1998. The significance of zinc for leukocyte biology. J. Leukoc. Biol. 64:571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fashner J, Ericson K, Werner S. 2012. Treatment of the common cold in children and adults. Am. Fam. Physician 86:153–159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazzerini M, Ronfani L. 2013. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1:CD005436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purchase R. 2013. The treatment of Wilson's disease, a rare genetic disorder of copper metabolism. Sci. Prog. 96:19–32. 10.3184/003685013X13587771579987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stefanidou M, Maravelias C, Dona A, Spiliopoulou C. 2006. Zinc: a multipurpose trace element. Arch. Toxicol. 80:1–9. 10.1007/s00204-005-0009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.