Abstract

In the present study, GRL008, a novel nonpeptidic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitor (PI), and darunavir (DRV), both of which contain a P2-bis-tetrahydrofuranyl urethane (bis-THF) moiety, were found to exert potent antiviral activity (50% effective concentrations [EC50s], 0.029 and 0.002 μM, respectively) against a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate of HIV-1 (HIVA02) compared to ritonavir (RTV; EC50, >1.0 μM) and tipranavir (TPV; EC50, 0.364 μM). Additionally, GRL008 showed potent antiviral activity against an HIV-1 variant selected in the presence of DRV over 20 passages (HIVDRVRP20), with a 2.6-fold increase in its EC50 (0.097 μM) compared to its corresponding EC50 (0.038 μM) against wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 (HIVWT). Based on X-ray crystallographic analysis, both GRL008 and DRV showed strong hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) with the backbone-amide nitrogen/carbonyl oxygen atoms of conserved active-site amino acids G27, D29, D30, and D30′ of HIVA02 protease (PRA02) and wild-type PR in their corresponding crystal structures, while TPV lacked H-bonds with G27 and D30′ due to an absence of polar groups. The P2′ thiazolyl moiety of RTV showed two conformations in the crystal structure of the PRA02-RTV complex, one of which showed loss of contacts in the S2′ binding pocket of PRA02, supporting RTV's compromised antiviral activity (EC50, >1 μM). Thus, the conserved H-bonding network of P2-bis-THF-containing GRL008 with the backbone of G27, D29, D30, and D30′ most likely contributes to its persistently greater antiviral activity against HIVWT, HIVA02, and HIVDRVRP20.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease (PR) is a critical viral component that is required for viral maturation and infectivity (1, 2). Due to rapid and error-prone viral replication, drug-resistant HIV-1 variants are inevitably selected during therapy with all currently available antiretroviral agents (3). Accumulation of mutations in the protease-encoding gene results in the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV-1 variants carrying a protease with an altered three-dimensional structure (4). Darunavir (DRV) (Fig. 1), the latest FDA-approved protease inhibitor (PI), which contains bis-tetrahydrofuranyl urethane (bis-THF) as the P2 moiety, has been shown to have a high genetic barrier (5, 6), a feature of a drug or regimen that delays or prevents the occurrence of genetic evolution of HIV-1 to acquire drug resistance-associated mutations, allowing the virus to overcome the antiretroviral activity of the very drug or regimen and to become capable of propagating despite treatment with the very drug or regimen. However, HIV-1 also ultimately develops high levels of resistance to DRV both in vitro and in vivo (7, 8). In order to suppress the propagation of such PI-resistant HIV-1 protease variants, the development of novel PIs with greater antiviral activities and higher genetic barriers is urgently needed.

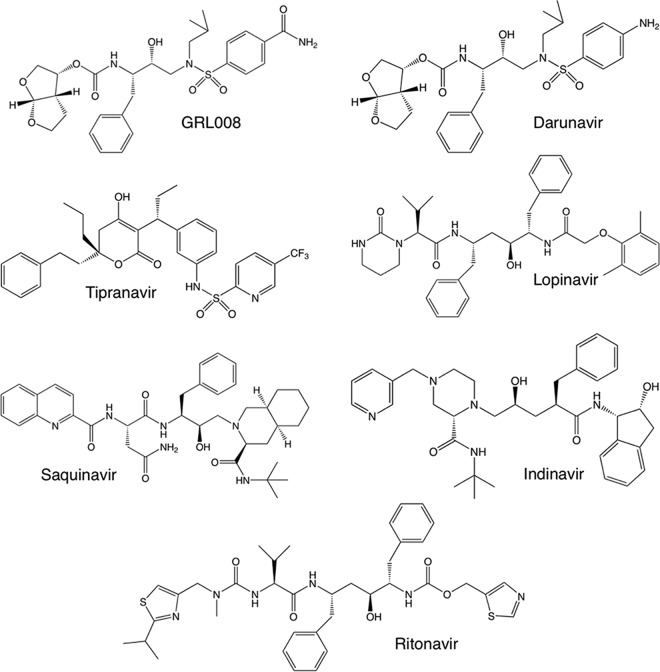

FIG 1.

Structures of protease inhibitors used in this study. GRL008 is a novel experimental HIV-1 PI, while DRV, tipranavir, lopinavir, saquinavir, indinavir, and ritonavir are FDA-approved PIs. Both GRL008 and DRV contain bis-THF as the P2 moiety. GRL008 and DRV contain benzene carboxamide and aniline, respectively, as the P2′ moieties.

Previously, two structurally related nonpeptidic PIs, GRL007 and GRL008, were designed based on the crystal structure of wild type HIV-1 protease (PRWT) in complex with DRV (PDB ID 4HLA) to replace one of the crystallographic bridging water molecules seen between the P2′ aniline moiety of DRV and G48′ of PRWT (9). Both GRL007 and GRL008 contain bis-THF as the P2 moiety, while the former has benzene carboxylic acid and the latter has benzene carboxamide as the P2′ moiety. Both compounds were evaluated against wild-type HIV-1 (HIVWT) (9). While both GRL007 and GRL008 showed greater enzyme inhibitory activities than the parent compound (DRV), GRL007 failed to inhibit the replication of HIVWT at up to 1 μM due to its poor cell penetration capability. On the other hand, GRL008 achieved higher intracellular concentrations as DRV comparably did and showed favorable antiviral activity against HIVWT (9).

In the present study, GRL008 (Fig. 1) was evaluated against an MDR clinical isolate of HIV-1 (HIVA02) (10, 11) that contained eight amino acid substitutions, L10I, K45R, I54V, L63P, A71V, V82T, L90M, and I93L, in its protease (PRA02). The antiviral activity of GRL008 was also evaluated against HIV-2ROD and an HIV-1 variant selected with DRV over 20 passages (HIVDRVRP20) (7). In addition, GRL008, DRV, ritonavir (RTV), and tipranavir (TPV) were individually cocrystallized with PRA02, and a structure-function evaluation of each agent was performed. Crystal structures of PRWT in complex with GRL008, DRV, RTV, and TPV were published previously, with the following Protein Data Bank (PDB) identification codes: 4I8Z, 4HLA, 1HXW, and 2O4P, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protease inhibitors.

Indinavir (IDV), lopinavir (LPV), RTV, saquinavir (SQV), and TPV were provided by the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. DRV was synthesized as described previously (12). GRL008 was synthesized by Arun K. Ghosh and coworkers (details of the synthetic procedures will be published separately).

Antiviral assays.

Antiviral assays were performed as described previously (9). Briefly, human MT-4 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum) and were exposed to HIVWT (HIV-1NL4–3), HIVA02, HIV-2ROD, or HIVDRVRP20 in the presence of various concentrations (1 μM, 100 nM, 10 nM, and 1 nM) of the PIs. Fifty TCID50 doses (the TCID50 is the inoculum size of HIV-1 that causes a cytopathic effect in 50% of the target cells, i.e., the 50% tissue culture infective dose) were used to infect the MT-4 cells. Infected cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence of PIs. An MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide)-based colorimetric assay was performed to assess cell viability on day 5. Assays were conducted in triplicate. The antiviral data are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Anti-HIVa activity of GRL008 in comparison with activities of FDA-approved protease inhibitors

| PI | Mean EC50 (μM) ± SD (fold change)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1NL4-3c | HIV-2ROD | HIV-1A02 | HIV-1DRVRP20 | |

| GRL008 | 0.038 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.006 | 0.029 ± 0.001 (0.8) | 0.097 ± 0.028 (2.6) |

| DRV | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.0057 ± 0.0028 | 0.002 ± 0.001 (2.0) | 0.05 ± 0.004 (50) |

| TPV | 0.128 ± 0.09 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 0.364 ± 0.14 (2.8) | 0.34 ± 0.03 (2.7) |

| LPV | 0.029 ± 0.01 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.474 ± 0.22 (16.3) | >1 (>34.0) |

| IDV | 0.039 ± 0.02 | ND | 0.526 ± 0.15 (13.5) | ND |

| RTV | 0.034 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | >1 (>29.0) | >1 (>29.0) |

| SQV | 0.017 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.107 ± 0.08 (6.3) | ND |

The amino acid substitutions identified in the proteases of HIV-1A02 and HIV-1DRVRP20 compared to the wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 were as follows: L10I/K45R/I54V/L63P/A71V/V82T/L90 M/I93L and L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/L63P/A71T/V82A/L89M, respectively.

The fold change is the ratio of the EC50 of the inhibitor against HIV-1A02 or HIV-1DRVRP20 and the corresponding EC50 against HIV-1NL4-3. ND, not determined.

The EC50s of GRL008, TPV, and SQV against wild-type HIV-1 (HIV-1NL4-3) were obtained from data previously published (9).

Expression and purification of PRA02.

Expression and purification of PRA02 was performed as described previously (9). Briefly, the inclusion bodies containing PRA02 were extracted with 3 M guanidine HCl (GnCl), the mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded on a Sephadex 200 column that was preequilibrated with 4 M GnCl. Protease-containing fractions were pooled and further purified by using a reverse-phase column. Fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the purity of PRA02 was determined to be >95%.

Protease refolding and cocrystallization with PIs.

Protease refolding was performed as described previously (9). Briefly, lyophilized PRA02 was dissolved in 1 ml of a 50% acetic acid solution and then added dropwise to 29 ml of refolding buffer (50 mM sodium acetate [pH 5.2], 5% ethylene glycol, 10% glycerol, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and a 10- to 20-fold molar excess of PI) while stirring on ice. Refolding was continued at 4°C with constant stirring overnight. The refolded protease-drug complex was concentrated using Amicon filters (3-kDa molecular mass cutoff) by centrifugation at 4,000 × g. The final protease concentration was determined to be 2 mg/ml. The hanging drop vapor diffusion method was used for cocrystallization of PRA02-drug complexes. Two microliters of the PRA02-drug complex was mixed with 2 μl of well solution per drop. Ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride grid screens (Hampton Research, CA) were used to obtain preliminary crystallization hits. Crystals were usually obtained in 1 to 2 days at room temperature (298 K). Cocrystals of PRA02 in complex with GRL008, DRV, TPV, or RTV were obtained using 1.6 M ammonium sulfate (in 0.1 M citric acid buffer at pH 5.0), 1 M sodium chloride (in 0.1 M citric acid buffer at pH 5.0), 2.4 M ammonium sulfate (in 0.1 M HEPES buffer at pH 7.0), and 3 M sodium chloride (in 0.1 M HEPES buffer at pH 7.0), respectively. Cocrystals were obtained as clusters of plates that were carefully dissociated using microtools, and individual crystals were picked up into nylon loops. Glucose (30%) was used as cryoprotectant for all the cocrystals. Cryo-coated cocrystals were instantaneously frozen in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray diffraction data collection and processing details.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory IL. Diffraction data for PRA02-GRL008 and PRA02-RTV were collected at the SER-CAT (Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team) facility, beam line 22-ID (insertion device; wavelength, 1.0 Å) equipped with a Mar300 charge-coupled-device (CCD) detector. Diffraction data for PRA02-TPV were collected at the LS-CAT (Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team) facility, beam line 21-ID (wavelength, 0.98 Å) equipped with an MX225 CCD detector, while the diffraction data for PRA02-DRV were collected using a Rigaku 007 HF rotating anode X-ray generator (Cu Kα wavelength, 1.54 Å) equipped with multilayer focusing mirrors and a Saturn A200 CCD detector. Sample temperature, crystal to detector distance, and frame width were 100 K, 200 mm, and 1°, respectively, at the synchrotron, while they were 95 K, 100 mm, and 0.5°, respectively, on the Rigaku generator. Diffraction data for PRA02-GRL008 and PRA02-RTV were processed and scaled using HKL2000 (13); data for PRA02-TPV and PRA02-DRV were processed using iMOSFLM (14) and scaled using SCALA (15) through the CCP4 interface (16, 17). Details of diffraction data processing results are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

X-ray diffraction data and structure refinement details for PRA02 in complex with GRL008, DRV, TPV, or RTV

| Parameter | PRA02-GRL008 | PRA02-DRV | PRA02-TPV | PRA02-RTV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB entry | 4NJS | 4NJT | 4NJU | 4NJV |

| Diffraction data | ||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 35.37–1.80 | 28.83–1.95 | 34.62–1.80 | 34.81–1.80 |

| Unit cell | ||||

| a (Å) | 44.632 | 44.95 | 45.35 | 45.952 |

| b (Å) | 57.995 | 57.60 | 57.54 | 58.219 |

| c (Å) | 88.111 | 86.48 | 86.70 | 86.866 |

| α (°) | 90.000 | 90.000 | 90.000 | 90.000 |

| β (°) | 90.030 | 90.020 | 90.020 | 90.020 |

| γ (°) | 90.000 | 90.000 | 90.000 | 90.000 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Solvent content (%) | 53.34 | 52.27 | 52.96 | 54.02 |

| No. of unique reflections | 41,155 (1,909)a | 31,996 (4,519) | 41,189 (5,915) | 40,844 (1,408) |

| Mean [I/σ(I)] | 23.1 (1.9) | 7.6 (2.1) | 10.1 (2.9) | 18.71 (1.8) |

| Rmergeb | 0.090 (0.478) | 0.097 (0.472) | 0.089 (0.456) | 0.089 (0.398) |

| Data redundancy | 3.8 (2.2) | 3.2 (2.8) | 4.2 (4.1) | 3.4 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.9 (92.3) | 98.5 (95.7) | 99.1 (98.6) | 96.6 (67.0) |

| Structure refinement data | ||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 35.37–1.80 | 22.47–1.95 | 34.62–1.80 | 34.81–1.80 |

| No. of reflections used | 40,957 | 31,875 | 41,166 | 40,761 |

| Rcrystc | 0.1823 | 0.1996 | 0.1840 | 0.1868 |

| Rfreed | 0.2161 | 0.2425 | 0.2211 | 0.2160 |

| No. of PRA02 dimers/AU | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| No. of protein atoms/AU | 3,044 | 3,064 | 3,044 | 3,064 |

| No. of ligand molecules/AU | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| No. of ligand atoms/AU | 80 | 76 | 84 | 200 |

| No. of water molecules | 378 | 420 | 375 | 359 |

| Mean temp factors | ||||

| Protein (Å2) | 22.538 | 18.339 | 20.142 | 21.705 |

| Main chains (Å2) | 20.390 | 16.818 | 17.930 | 19.213 |

| Side chains (Å2) | 24.870 | 19.966 | 22.542 | 24.373 |

| Ligand (Å2) | 17.672 | 15.725 | 16.28 | 22.574 |

| Water molecules (Å2) | 32.114 | 26.305 | 30.263 | 31.957 |

| RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| RMSD bond angle (Å) | 1.160 | 1.261 | 1.185 | 1.279 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||

| Most favored (%) | 97.8 | 96.5 | 98.1 | 97.8 |

| Additional allowed (%) | 1.9 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σ|I − <I>|/ΣI.

Rcryst = Σ ‖Fobs| − |Fcalc‖/Σ|Fobs|.

A test set of 5% of the reflections was used for the Rfree analysis.

Structure solutions and refinement.

Structure solutions were obtained by the molecular replacement (MR) method. Initial MR was performed using MOLREP (18) through the CCP4 interface for PRA02 with the protease taken from PDB ID 4HLA as a search model. Amino acid substitutions were modeled into 4HLA by using Maestro (version 9.3; Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY). Final MR solution of PRA02 was obtained using BALBES (19), an automated molecular replacement pipeline available from the York Structural Biology Laboratory server (http://www.york.ac.uk/chemistry/research/ysbl). Structure solutions were directly refined using REFMAC5 (20) through the CCP4 interface. Initial coordinates for GRL008, DRV, RTV, and TPV were taken from crystal structures (PDB IDs 4I8Z, 4HLA, 1HXW, and 2O4P, respectively). The PIs were fit into the electron density by using ARP/wARP ligands (21, 22) through the CCP4 interface. Refinement libraries for GRL008 were prepared using the PRODRG server (23) as described previously (9). Solvent molecules were built using the ARP/wARP solvent-building module through the CCP4 interface. After building water molecules, the final models were refined using the simulated annealing method from phenix.refine (Phenix, version 1.8.2-1309) (24) on the NIH Biowulf Linux cluster. Details of the refinement statistics are given in Table 2. The final refined structures were used for structural analysis. Hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) were calculated by using cutoff values for distance (maximum distance between the donor and acceptor heavy atoms was 3.0 Å) and angles (minimum donor, 90°, and minimum acceptor, 60°). H-bonds with a distance of >3.0 Å were considered as weak interactions. Hydrophobic contacts were calculated between two carbon atoms (one from PI and one from PRWT or PRA02) with a 4-Å distance cutoff.

Protein structure accession numbers.

The final refined coordinates for the crystal structures of PRA02-GRL008, PRA02-DRV, PRA02-TPV, and PRA02-RTV were deposited in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) under accession IDs 4NJS, 4NJT, 4NJU, and 4NJV, respectively.

RESULTS

GRL008 is highly active against HIVA02.

Cell-based antiviral assays using human MT-4 cells exposed to HIVA02 revealed that GRL008 is highly active against HIVA02, with an EC50 of 0.029 μM. GRL008 and DRV, both of which contain a P2 bis-THF moiety, had <1- and 2-fold changes in their EC50s against HIVA02 compared to their corresponding EC50s against HIVWT (Table 1). In contrast, as shown in Table 1, the EC50s of RTV against HIVWT and HIVA02 were 0.034 μM and >1 μM, respectively, resulting in a >29-fold increase in the EC50 against HIVA02. Similarly, LPV and IDV showed >16- and >13-fold increases in their EC50s, respectively, against HIVA02 in comparison to their corresponding EC50s against HIVWT. Although lesser changes in the EC50s were seen for IDV than for LPV, the EC50 of IDV (0.526 μM) was still greater than that of LPV (0.474 μM) against HIVA02. TPV and SQV showed 2.8- and >6-fold changes, respectively, in their EC50s against HIVA02 compared to their corresponding EC50s against HIVWT. However, SQV had greater antiviral potency against HIVA02 (EC50, 0.107 μM) than TPV (EC50, 0.364 μM). Among the seven PIs tested, based on their antiviral activities, RTV, LPV, IDV, and TPV were the least effective against HIVA02, all with EC50s in the high nanomolar concentration range (364 nM to >1,000 nM). The substantial changes in the EC50s for these drugs demonstrate the multidrug resistance profile of HIVA02. Comparative analysis of the EC50s against HIVA02 given in Table 1 shows that the antiviral potency of GRL008 is >34-fold higher than RTV, >16-fold higher than LPV, >18-fold higher than IDV, 3.7-fold higher than SQV, and >12-fold higher than TPV. These results suggest that GRL008 has a desirable genetic barrier similar to that of DRV and can effectively inhibit multi-PI-resistant strains of HIV-1, such as HIVA02.

GRL008 shows favorable antiviral activities against HIV-2ROD and HIVDRVRP20.

The favorable antiviral activity of GRL008 against HIVWT and HIVA02 prompted us to further evaluate it against HIV-2ROD and HIVDRVRP20. Antiviral assays using human MT-4 cells exposed to either HIV-2ROD or HIVDRVRP20 showed that GRL008 was equipotent against HIVWT (EC50, 0.038 μM) and HIV-2ROD (EC50, 0.03 μM). LPV showed slightly better antiviral activity (EC50, 0.014 μM) than GRL008 against HIV-2ROD. Both TPV and RTV showed lesser antiviral activities against HIV-2ROD, with EC50s of 1.8 μM and 0.26 μM, respectively. While DRV showed a 50-fold increase in its EC50 against HIVDRVRP20 (0.05 μM) compared to its EC50 against HIVWT (0.001 μM), GRL008 showed only a 2.6-fold increase in its EC50 against HIVDRVRP20 (0.097 μM) compared to its EC50 against HIVWT (0.038 μM). TPV showed a 2.7-fold increase in its EC50 against HIVDRVRP20 (0.34 μM) compared to its EC50 against HIVWT (0.128 μM). However, GRL008 showed a 3.5-fold-greater antiviral activity against HIVDRVRP20 than TPV. RTV failed to inhibit HIVDRVRP20 even at a 1.0 μM concentration. These results suggest that GRL008 has a greater genetic barrier than most of the PIs evaluated in this study.

Crystal structures of PRA02 in complex with PIs.

Crystal structures of PRA02 in complex with GRL008, RTV, or TPV were solved to a resolution of 1.8 Å, while the structure of PRA02 in complex with DRV was solved to a resolution of 1.95 Å (Table 2). All structures were solved in the space group P21, with two dimers of PRA02 per asymmetric unit (AU), in agreement with the predicted number of PRA02 dimers per Matthew's coefficient values (25), which were precalculated before molecular replacement. As shown in Fig. S1a, in the supplemental material, the overall R factors (wRfac), as calculated using MOLREP, were high, with low scores when one PRA02 dimer per AU was obtained as a solution. When two dimers of PRA02 per AU were obtained as a solution, the wRfac values decreased, with a relatively proportional increase in the corresponding scores (see Fig. S1a) for each of the structure solutions. No significant root mean square deviation (RMSD) in the Cα atoms of the two PRA02 dimers within the AU was observed for any of the four structure solutions (see Fig. S1b). RMSD values of <1.0 Å were considered biologically insignificant. Continuous difference electron density was observed for GRL008, DRV, RTV, and TPV, with map correlation coefficient values of 0.94, 0.89, 0.78, and 0.88, respectively, in their corresponding maps. Based on the electron density maps, one molecule of GRL008, DRV, or TPV was fit into the active site of each PRA02 dimer. On the other hand, two molecules of RTV were fit into the active site of each PRA02 dimer. Thus, two molecules of GRL008, DRV, or TPV were fit per AU, while four molecules of RTV were fit per AU. The Rcryst and Rfree values improved significantly (see Fig. S1c and d, respectively) with the two-step refinement of structure solutions containing two PRA02 dimers per AU. The RMSDs in bond lengths and bond angles significantly improved (Table 2) by using the libraries for ligands that were geometry optimized through the semiempirical quantum mechanical method of refinement, eLBOW-AM1 (26) during refinement conducted using phenix.refine. Ramachandran plots showed no significant deviations for the protein, suggesting an overall good quality of stereochemistry.

GRL008, DRV, and TPV showed minor changes in their binding profiles in the active site of PRA02 compared to their interactions with PRWT.

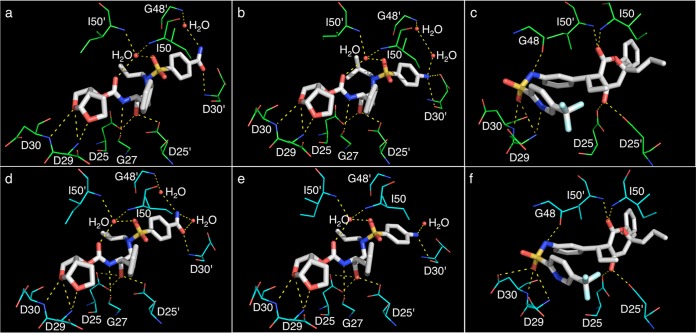

Crystal structures of PRA02 in complex with GRL008, DRV, or TPV showed two PRA02 dimers per AU, with each PRA02 dimer bound to one molecule of the PI. No major differences in the binding profiles of three PIs were seen between the two PRA02 dimers (within the AU) in their corresponding structures. As shown in Fig. 2, the P2 bis-THF moiety of GRL008 (panel d) and DRV (panel e) showed three strong H-bonds with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 (two contacts) and D30 (one contact). In the case of TPV, two strong H-bonds, one each with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 and D30, were seen (Fig. 2f). TPV showed two additional H-bonds in the S2 binding pocket of PRA02, one with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of G48 and one with the side chain δ-oxygen atom of D30 (Fig. 2f). One strong H-bond with G27 was seen for both GRL008 and DRV but not for TPV. The P2′ moieties, benzene carboxamide (GRL008) and aniline (DRV), showed one strong H-bond each with the backbone amide nitrogen and the backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms of D30′, respectively. TPV, due to lack of P2′ polar atoms, did not show any H-bonds in the S2′ binding pocket of PRA02. The transition-state mimic hydroxyl group of all three PIs showed at least one H-bond each with the δ-oxygen atoms from the side chains of both D25 and D25′ (Fig. 2d, e, and f). Both GRL008 and DRV showed two H-bonds each, with a conserved bridging water molecule, which in turn had H-bonds with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of the PRA02 flap residues, I50 and I50′ (Fig. 2d and e). TPV showed direct H-bonds with I50 and I50′ (Fig. 2f) without a bridging water molecule, as seen in its corresponding wild-type protease structure (PDB ID 2O4P) (Fig. 2c). In addition, the P2′ moieties of GRL008 and DRV showed H-bonds with two and one water molecules, respectively. In the case of GRL008, one of the water molecules, interacting with its P2′ moiety, showed a bridging H-bond with the backbone amide nitrogen atom of G48′ (Fig. 2d). As shown in Fig. 2a, a similar profile was seen in the crystal structure of PRWT in complex with GRL008 (PDB ID 4I8Z). As shown in Fig. 2b, DRV showed two water molecules and an H-bonding network between the P2′ aniline moiety and G48′ of PRWT (PDB ID 4HLA). However, as shown in Fig. 2e, such an H-bonding network was not seen in the crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with DRV (PDB ID 4NJT). No major changes in the binding orientation were seen for any of the three PIs compared to their corresponding binding profiles against PRWT.

FIG 2.

Hydrogen bonding profiles of GRL008, DRV, and TPV. H-bonds formed by GRL008, DRV, and TPV with PRWT (a, b, and c, respectively) and with PRA02 (d, e, and f, respectively) in their corresponding crystal structures are shown as yellow dashed lines. In all panels, the carbon atoms of the inhibitors are shown as white thick sticks, while the corresponding carbon atoms of PRWT and PRA02 residues are shown as green and cyan thin sticks, respectively. Nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and fluorine atoms are shown as blue, red, yellow, and light cyan sticks, respectively. Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red spheres. All H-bonds were calculated as the distances between two heavy atoms, with a maximum distance cutoff of 3.0 Å and minimum angle cutoff for donor of 90° and for acceptor of 60°. The P2 bis-THF moiety of GRL008 and DRV shows three conserved H-bonds with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 and D30 in both PRWT (a and b) and PRA02 (d and e). While TPV shows similar three H-bonds with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 and D30 in PRWT (c), the sulfonyl oxygen of TPV shows two H-bonds, one each with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of D29 and D30 and one H-bond with the side chain δ-oxygen atom of D30 from PRA02 (f). Additionally, the P2′ moieties of GRL008 and DRV show one conserved H-bond, each with the backbone of D30′ (a, b, d, and e). Both GRL008 and DRV have a direct H-bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of G27 (a, b, d, and e). No H-bonds with D30′ or G27 were seen with TPV; instead, three direct H-bonds, one each with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of G48 and the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of I50 and I50′, were seen with TPV (c and f). In the cases of GRL008 and DRV, bridging H-bonds were seen with the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of I50 and I50′ via a conserved water molecule (a, b, d, and e). While the P2′ benzene carboxamide moiety of GRL008 showed a conserved bridging H-bond with G48′ from both PRWT and PRA02 via a water molecule (a and d, respectively), such conserved bridging H-bonds were not seen for the P2′ aniline moiety of DRV with G48′ of PRA02 (e). Overall, no significant changes in the H-bonding profiles were seen for GRL008, DRV, and TPV against PRA02 compared to their profiles against PRWT in their respective crystal structures.

As shown in Fig. 3, both GRL008 and DRV showed conserved hydrophobic interactions with residues L23, V32, G49, T82, L23′, A28′, V32′, T82′, and I84′ in the corresponding S1, S2, S1′, and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. GRL008 showed additional hydrophobic interactions with residues A28 and I50, while DRV showed additional hydrophobic interactions with residues D29 and P81′. Overall, the profiles of hydrophobic contacts for GRL008 and DRV were similar to their corresponding profiles against PRWT structures, PDB IDs 4I8Z and 4HLA, respectively. TPV is involved in multiple hydrophobic interactions with residues R8, L23, A28, D29, V32, G49, I50, P81, T82, R8′, G27′, A28′, V32′, G49′, I50′, and I84′ in the corresponding S1, S2, S1′, and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. No significant deviation was seen in the profile of hydrophobic contacts for TPV against PRA02 compared to its corresponding profile against PRWT structure (PDB ID 2O4P). Thus, the binding profiles of GRL008, DRV, and TPV in the active site of PRA02 were comparable to their corresponding profiles in the active site of PRWT.

FIG 3.

Hydrophobic interactions of GRL008 and DRV. (a and b) Profiles of hydrophobic interactions for GRL008 (a) and DRV (b) in the active site of PRA02 and PRWT. The protease binding pockets (S2, S1, S1′, and S2′) are shown as arcs and are labeled. The corresponding protease amino acids that form the hydrophobic contacts with either GRL008 or DRV are listed for each binding pocket accordingly. Residues shown in green are from PRWT structures (PDB IDs 4I8Z and 4HLA for GRL008 and DRV, respectively), while the residues in red are from PRA02. In both panels, the amino acid residues are labeled 1 to 99 for monomer 1 and 1′ to 99′ for monomer 2. Both GRL008 and DRV showed slightly altered but persistent contacts in all the binding pockets that were comparable to their corresponding wild-type profiles, thus supporting their higher antiviral activities.

RTV shows an altered binding orientation in the active site of PRA02.

The crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with RTV showed two PRA02 dimers per AU. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, the P2′ thiazolyl moiety of RTV showed two alternate binding orientations, RTV-1 and RTV-2, in the active site of PRA02. Superposition of RTV-1 onto RTV-2 is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material for clarity. RTV-1 (Fig. 4a) showed a previously reported binding orientation seen in the active site of PRWT (PDB ID 1HXW). RTV-2 (Fig. 4b) shows the altered binding of the P2′ thiazolyl moiety, which contributes to a significant loss of contacts in the S2 and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. In order to verify the alternate conformations of the P2′ thiazolyl group of RTV, the average individual B factors of all five atoms (C1, C2, S3, C4, and N5) from the P2′ thiazolyl group were analyzed (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) and it was found that the individual B factors support the two conformations.

FIG 4.

Hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts for RTV in the active site of PRA02. (a and b) H-bonds made by RTV-1 (a) and RTV-2 (b) (alternate conformations of the P2′ thiazolyl moiety of RTV, highlighted by red circles) in the active site of PRA02. In both panels, the carbon atoms of RTV are shown as white thick sticks, while the carbon atoms of corresponding amino acid residues from PRA02 are shown as green thin sticks. Nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms are shown as blue, red, and yellow sticks, respectively. Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red spheres, and the H-bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines. While RTV-1 (a) showed a profile comparable to its corresponding profile with PRWT (PDB ID 1HXW), RTV-2 (b) showed an altered binding orientation for the P2′ thiazolyl group, with an average root mean square deviation of 3 Å, resulting in loss of a critical H-bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of D30′. The P3 isopropyl group also showed a slightly altered binding orientation but was not biologically significant. (c) Profile of hydrophobic contacts made by RTV in the active sites of PRWT and PRA02. The binding pockets are represented as arcs and are labeled accordingly. The corresponding amino acids from PRWT and PRA02 that are involved in hydrophobic interactions with RTV are shown in green and red, respectively. For PRA02, only RTV-2 is shown here because the binding profile of RTV-1 in the active site of PRA02 is similar to that of its corresponding profile in the active site of PRWT. RTV-2 showed significant loss of contacts in the S2 and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02, thus supporting its weaker antiviral activity. Superposition of RTV-1 and RTV-2 is shown in Fig. S2 of the supplemental material.

Two conserved H-bonds, one with the backbone amide nitrogen atom of D29 and one with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of G48, were seen for both RTV-1 and RTV-2 in the S2 binding pocket of PRA02. Two and one H-bonds were seen with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms of G27 and G27′, respectively, for both RTV-1 and RTV-2. The transition-state mimic hydroxyl group of both RTV-1 and RTV-2 showed one H-bond each with the side-chain δ-oxygen atoms of both D25 and D25′. The P2′ thiazolyl group of RTV-2 showed a significant change in the binding orientation, with an average RMSD of 3 Å compared to that of RTV-1, resulting in loss of a critical H-bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of D30′. Both RTV-1 and RTV-2 showed a conserved water molecule that bridges H-bonds between RTV and the backbone amide nitrogen atoms of I50 and I50′. Two additional water molecules were seen for both RTV-1 and RTV-2 that are involved in H-bonding with the P3 and P2 moieties of RTV. Overall, the profiles of H-bonds for both RTV-1 and RTV-2 were similar to that of the wild-type structure (PDB ID 1HXW). However, the P2′ moiety of RTV-2 showed major conformational changes that resulted in the loss of a critical H-bond with D30′.

As shown in Fig. 4c, RTV-1 showed a profile of hydrophobic contacts similar to that of RTV, based on the PRWT crystal structure (PDB ID 1HXW), while RTV-2 showed loss of hydrophobic contacts in the S1, S2, and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. The isopropyl group from the P3 isopropylthiazolyl moiety showed minor changes in binding orientation, with an average RMSD of 1 Å, but still maintained hydrophobic contacts with Pro81. Nine amino acids (D29, G49, T82, I84, R8′, G49′ I50′, P81′, and T82′) from the S3, S1, and S1′ binding pockets of PRA02 showed conserved hydrophobic interactions with both RTV-1 and RTV-2. RTV-2 showed complete loss of hydrophobic contacts in the S2 and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. Thus, the loss of contacts in the S1, S2, and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02 should well explain the loss of antiviral activity of RTV against HIVA02.

DISCUSSION

The present structure-function data provide insights into the structural basis for the greater antiviral activity of a P2 bis-THF-containing novel PI, GRL008, and should help us understand the drug resistance mechanism of the clinical isolate HIVA02 toward RTV and other PIs. HIVA02 was initially isolated at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center from a treatment-experienced male patient (age 44 years) who had been heavily treated with the PIs IDV, RTV, and SQV, along with reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors abacavir (ABC), 3′-azido-2′-dideoxythymidine (AZT), 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI), 3′-thiacytidine (3TC), 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC), and 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (d4T), as a part of 39-month antiviral therapy (10). Antiviral assays with viral isolates obtained by culturing the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the patient's blood sample showed 4- to >5,000-fold-increased resistance against IDV, RTV, SQV, and the RT inhibitors mentioned above (10). In the present study, the antiviral assays showed that both GRL008 and DRV, which contain the bis-THF group as the P2 moiety, were highly active with a desirable genetic barrier against HIVA02, with no significant change in their EC50s against HIVA02 compared to those against HIVWT. LPV was much less effective in inhibiting the replication of HIVA02 than inhibiting HIVWT replication in the cell-based antiviral assays. The lower antiviral activity of LPV against HIVA02 could be partially attributed to its structural resemblance to RTV, which was used in the treatment regimen of the patient described above. Although TPV was able to inhibit the replication of HIVA02, GRL008 was found to be >12-fold more potent than TPV in this cell-based antiviral assay. As predicted, HIVA02 was resistant to IDV, RTV, and SQV, in view of the fact that the patient failed the treatment with these three PIs. Achievement of higher anti-HIV-1 activity and a greater genetic barrier in combination with lower cytotoxicity and high oral bioavailability represent major critical goals in the design of novel PIs. For example, TMC-126, an analog of DRV that contains P2 bis-THF and P2′ methoxy benzene groups, was previously shown to have a greater antiviral potency than DRV, with a desirable genetic barrier (27), but could not be used further due to its poor oral bioavailability. Similarly, GRL007 (an analog of GRL008) showed poor cell penetration properties in spite of its picomolar enzyme inhibitory activity (9). It is noteworthy that GRL008 has a desirable therapeutic window due to its greater antiviral activity, lower cytotoxicity (50% cyotoxic concentration, >100 μM), and greater cell penetration capability, similar to that of DRV (9), thus making it a desirable compound to be further evaluated against multi-PI-resistant strains of HIV-1, including DRV-resistant strains.

It was previously noted that DRV resistance-associated amino acid substitutions are not clinically seen and the correlation for the occurrence of such DRV resistance-associated amino acid substitutions in conjunction with other PI resistance amino acid substitutions (such as L10I, I54V, V82T, and L90M, which are seen in PRA02) is very low (8). However, we recently selected a highly DRV-resistant strain of HIV-1 in vitro by using a mixture of multi-PI-resistant (but DRV-sensitive) clinical HIV-1 strains as a starting viral population (7). In an attempt to examine the genetic barrier of GRL008, it was further evaluated against one of the DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants, HIVDRVRP20 (7) and was found to be potent, with only a 2.6-fold increase in its EC50 above that for HIVWT. Although TPV showed a similar 2.7-fold increase in its EC50 against HIVDRVRP20, the absolute EC50 of GRL008 was 3.5-fold lower than that of TPV, suggesting that GRL008 is overall a better PI than TPV against HIVDRVRP20.

The P2 bis-THF moiety of both GRL008 and DRV showed strong H-bonds with the backbone of conserved active-site amino acids D29 and D30 of PRA02. The P2′ benzene carboxamide moiety of GRL008 was designed to replace one of the bridging water molecules seen with DRV (Fig. 2a and b) in the S2′ pocket (9). In the present study, the crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with GRL008 showed a conserved profile of a bridging H-bond with G48′ via a water molecule (Fig. 2d), as was seen in its corresponding interactions with PRWT (PDB ID 4I8Z) (Fig. 2a). This suggests that the amino acid substitutions in PRA02 do not affect the binding profile of GRL008 in either the S2 or S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. On the other hand, of the two bridging water molecules in the S2′ pocket of PRWT in complex with DRV (PDB ID 4HLA) (Fig. 2b), only one was seen in the structure of PRA02 in complex with DRV (Fig. 2e). Taken together, the crystal structures confirmed that both GRL008 and DRV, bound in the active site of PRA02, do not have notable changes in their binding orientations; this evidence thus supports their greater conserved antiviral activities. These structural analyses may further explain in part the conserved and greater antiviral activity of GRL008 against HIVDRVRP20.

The crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with TPV did not show major changes in the binding orientation of TPV (Fig. 2f) compared to that with PRWT (PDB ID 2O4P) (Fig. 2c). However, the EC50 of TPV against HIVA02 was >12-fold greater than that of GRL008. The P2′ region of TPV lacks polar groups, and hence no H-bonds were seen in the S2′ binding pocket of either PRA02 or PRWT, while both GRL008 and DRV showed persistent, strong H-bonds with the backbone of D30′ in the S2′ binding pocket of PRA02. TPV has been shown to have a greater genetic barrier against multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants due to its unique mechanism of minor loss of binding affinity through entropy/enthalpy compensation against amino acid substitutions in the protease (28). In the present study, TPV showed a 2.8-fold change in its EC50 against HIVA02 versus HIVWT, while GRL008 and DRV showed <1- and 2-fold changes, respectively, in their EC50s against HIVA02. Furthermore, based on Lipinski's rule of five (29) and the logP values of TPV (7.0) and DRV (2.9) obtained from the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), it is apparent that DRV and analogs such as GRL008 have favorable oral bioavailabilities in addition to greater antiviral potencies than TPV against HIVA02.

In this study, IDV, RTV, and SQV showed much lower antiviral activities against HIVA02 than against HIVWT (Table 1). In particular, RTV showed a >29-fold increase in its EC50 against HIVA02 compared to its EC50 against HIVWT. In order to understand the RTV resistance mechanism of HIVA02, the crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with RTV was solved and analyzed. Morissette et al. previously showed that RTV undergoes a conformational polymorphism (30) that lowers its solubility and compromises its anti-HIV-1 activity. In the present study, the EC50 of RTV against HIVWT (Table 1) was within 2-fold of the EC50s of LPV, IDV, and SQV against HIVWT, suggesting that the lowered solubility of RTV may not play a critical role in the loss of its activity against HIVA02. The crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with RTV showed an altered binding orientation of the P2′ thiazolyl moiety of RTV in the S2′ binding pocket of PRA02 (Fig. 4a and b), with an RMSD of 3 Å. In order to understand the binding profiles of RTV, the crystal structure of PRA02 in complex with RTV was compared in detail to its corresponding wild-type structure (PDB ID 1HXW). In the case of the PRA02 structure, the H-bond between the P2′ thiazolyl group of RTV and D30′ was seen for RTV-1 (Fig. 4a), which closely resembled its corresponding binding orientation in the active site of PRWT (PDB ID 1HXW). On the other hand, the H-bond between the P2′ thiazolyl moiety of RTV-2 and D30′ of PRA02 was lost (Fig. 4b). This loss of contact was not seen in the case of RTV interactions with PRWT (PDB ID 1HXW), suggesting that the conformational polymorphism of RTV may not be the reason for loss of its antiviral activity against HIVA02.

Based on the binding profile of RTV-1, one could hypothesize that RTV-1 (Fig. 4a) inhibits the replication of HIVA02 at least by 50% due to its close resemblance to its corresponding wild-type structure (PDB ID IHXW). However, it has been shown previously that the presence of less than 25% of active viral protease can support viral propagation, due to the formation of mature and infectious viral particles (31). Additionally, mutations at codons 10, 54, 63, 71, 82, and 84 have been known to cause HIV-1 resistance against RTV (32), and PRA02 consists of amino acid substitutions L10I, I54V, L63P, A71V, and V82T. The combination of active-site and non-active-site amino acid substitutions has been shown to cause a significant loss of binding affinity to RTV (42- to 1,330-fold increase in the Ki values compared to that for PRWT) due to loss of direct contacts as well as altered protease-flap dynamics (33, 34). As shown in Fig. 4b, RTV-2 has a complete loss of direct contacts in the S2 and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02. Furthermore, the substitution L63P has been previously shown to enhance viral fitness in combination with L90M (35). PRA02 contains both amino acid substitutions L63P and L90M. Thus, the enhanced replication fitness of HIVA02 in combination with loss of contacts for RTV in the active site of PRA02 may well explain the compromised activity of RTV (EC50, >1 μM) against HIVA02 in the antiviral assays. In the case of patients, a study based on the Abbott M97-720 trial showed that low-level viremia could persist at least for 7 years in patients on an LPV/RTV regimen, partially due to latent viral reservoirs (36). Based on our structural analysis, amino acid substitutions (both active site and non-active site) in PRA02 caused an altered binding orientation of RTV in the active site, resulting in a significant loss of contacts in the S2 and S2′ binding pockets of PRA02 and, consequently, causing HIV-1 resistance to RTV. Thus, our present data not only explain the mechanism for RTV resistance but also help explain the retained antiviral potency of a novel P2 bis-THF-containing PI (GRL008) against HIVA02.

In conclusion, the conserved H-bonding network of P2 bis-THF-containing PIs, such as GRL008 and DRV, with the backbone of conserved active-site amino acids G27, D29, D30, and D30′ of PRA02 and PRWT most likely contributes to their antiviral activities against HIVA02 and HIVWT, with minimal changes in the EC50s. In particular, GRL008 proved to have a favorable antiviral activity against HIVDRVRP20, a finding that warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (H.M.), by a grant for the Global Education and Research Center aiming at the control of AIDS (Global Center of Excellence supported by Monbu-Kagakusho), Promotion of AIDS Research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan, by a grant to the Cooperative Research Project on Clinical and Epidemiological Studies of Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (Renkei Jigyo; grant 78, Kumamoto University) of Monbukagakusho (H.M.), and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM53386; A.K.G.).

We thank the Advanced Photon Source (APS) for X-ray diffraction data collection. Use of the APS was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 (LS-CAT) and contract W-31-109-Eng-38 (SER-CAT). Use of LS-CAT sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (grant 085P1000817). Supporting institutions for SER-CAT may be found at www.ser-cat.org/members.html. We thank the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent program for providing IDV, LPV, RTV, SQV, and TPV. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 April 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00107-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, Davis LJ, Heimbach JC, Dixon RA, Scolnick EM, Sigal IS. 1988. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:4686–4690. 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng C, Ho BK, Chang TW, Chang NT. 1989. Role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protease in core protein maturation and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 63:2550–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shafer RW, Rhee SY, Pillay D, Miller V, Sandstrom P, Schapiro JM, Kuritzkes DR, Bennett D. 2007. HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase mutations for drug resistance surveillance. AIDS 21:215–223. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011e691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yedidi RS, Proteasa G, Martinez JL, Vickrey JF, Martin PD, Wawrzak Z, Liu Z, Kovari IA, Kovari LC. 2011. Contribution of the 80s loop of HIV-1 protease to the multidrug-resistance mechanism: crystallographic study of MDR769 HIV-1 protease variants. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67:524–532. 10.1107/S0907444911011541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, Ogata H, Bilcer G, Devasamudram T, Kincaid JF, Boross P, Wang Y-F, Tie Y, Volarath P, Gaddis L, Harrison RW, Weber IT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2003. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethan-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3123–3129. 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh AK, Anderson DD, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. 2012. Enhancing protein backbone binding: a fruitful concept for combating drug-resistant HIV. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51:1778–1802. 10.1002/anie.201102762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh Y, Amano M, Towata T, Danish M, Leshchenko-Yashchuk S, Das D, Nakayama M, Tojo Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2010. In vitro selection of highly darunavir-resistant and replication-competent HIV-1 variants by using a mixture of clinical HIV-1 isolates resistant to multiple conventional protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 84:11961–11969. 10.1128/JVI.00967-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsuya Y, Liu TF, Rhee SY, Fessel WJ, Shafer RW. 2007. Prevalence of darunavir resistance-associated mutations: patterns of occurrence and association with past treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1177–1179. 10.1086/521624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yedidi RS, Maeda K, Fyvie WS, Steffey M, Davis DA, Palmer I, Aoki M, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Garimella H, Das D, Wingfield PT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2013. P2′ benzene carboxylic acid moiety is associated with decrease in cellular uptake: evaluation of novel nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors containing P2 bis-tetrahydrofuran moiety. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:4920–4927. 10.1128/AAC.00868-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshimura K, Kato R, Yusa K, Kavlick MF, Maroun V, Nguyen A, Mimoto T, Ueno T, Shintani M, Falloon J, Masur H, Hayashi H, Erickson J, Mitsuya H. 1999. JE-2147: a dipeptide protease inhibitor (PI) that potently inhibits multi-PI-resistant HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:8675–8680. 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis DA, Brown CA, Singer KE, Wang V, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield P, Maeda K, Harada S, Yoshimura K, Kosalaraksa P, Mitsuya H, Yarchoan R. 2006. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by a peptide dimerization inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. Antiviral Res. 72:89–99. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh AK, Leshchenko S, Noetzel M. 2004. Stereoselective photochemical 1,3-dioxolane addition to 5-alkoxymethyl-2(5H)-furanone: synthesis of bis-tetrahydrofuranyl ligand for HIV protease inhibitor UIC-94017 (TMC-114). J. Org. Chem. 69:7822–7829. 10.1021/jo049156y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326. 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie AG. 2006. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:48–57. 10.1107/S0907444905039107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:72–82. 10.1107/S0907444905036693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. 2003. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:1131–1137. 10.1107/S0907444903008126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67:235–242. 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. 1997. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30:1022–1025. 10.1107/S0021889897006766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. 2008. BALBES: a molecular replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64:125–132. 10.1107/S0907444907050172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53:240–255. 10.1107/S0907444996012255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamzin VS, Wilson KS. 1993. Automated refinement of protein models. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 49:120–147. 10.1107/S0907444992006747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwart PH, Langer GG, Lamzin VS. 2004. Modelling bound ligands in protein crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2230–2239. 10.1107/S0907444904012995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DMF. 2004. PRODRG: a tool for high throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:1355–1363. 10.1107/S0907444904011679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:213–221. 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews BW. 1968. Solvent content of protein crystals. J. Mol. Biol. 33:491–497. 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. 2009. Electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65:1074–1080. 10.1107/S0907444909029436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura K, Kato R, Kavlick MF, Nguyen A, Maroun V, Maeda K, Hussain KA, Ghosh AK, Gulnik SV, Erickson JW, Mitsuya H. 2002. A potent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor, UIC-94003 (TMC-126), and selection of a novel (A28S) mutation in the protease active site. J. Virol. 76:1349–1358. 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1349-1358.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzammil S, Armstrong AA, Kang LW, Jakalian A, Bonneau PR, Schmelmer V, Amzel LM, Freire E. 2007. Unique thermodynamic response of tipranavir to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease drug resistance mutations. J. Virol. 81:5144–5154. 10.1128/JVI.02706-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. 2001. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46:3–26. 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morissette SL, Soukasene S, Levinson D, Cima MJ, Almarsson O. 2003. Elucidation of crystal form diversity of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir by high-throughput cyrstallization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:2180–2184. 10.1073/pnas.0437744100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose JR, Babe LM, Craik CS. 1995. Defining the level of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease activity required for HIV-1 particle maturation and infectivity. J. Virol. 69:2751–2758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmit JC, Ruiz L, Clotet B, Raventos A, Tor J, Leonard J, Desmyter J, De Clercq E, Vandamme AM. 1996. Resistance-related mutations in the HIV-1 protease gene of patients treated for 1 year with the protease inhibitor ritonavir (ABT-538). AIDS 10:995–999. 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzammil S, Ross P, Freire E. 2003. A major role for a set of non-active site mutations in the development of HIV-1 protease drug resistance. Biochemistry 42:631–638. 10.1021/bi027019u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clemente JC, Moose RE, Hemrajani R, Whitford LRS, Govindasamy L, Reutzel R, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M, Goodenow MM, Dunn BM. 2004. Comparing the accumulation of active- and nonactive-site mutations in the HIV-1 protease. Biochemistry 43:12141–12151. 10.1021/bi049459m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Picado J, Savara AV, Sutton L, D'Aquila RT. 1999. Replication fitness of protease inhibitor-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:3744–3752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer S, Maldarelli F, Wiegand A, Bernstein B, Hanna GJ, Brun SC, Kempf DJ, Mellors JW, Coffin JM, King MS. 2008. Low-level viremia persists for at least 7 years in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3879–3884. 10.1073/pnas.0800050105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.