Abstract

Background

Echinacea plant preparations (family Asteraceae) are widely used in Europe and North America for common colds. Most consumers and physicians are not aware that products available under the term Echinacea differ appreciably in their composition, mainly due to the use of variable plant material, extraction methods and the addition of other components.

Objectives

To assess whether there is evidence that Echinacea preparations are effective and safe compared to placebo in the prevention and treatment of the common cold.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL 2013, Issue 5, MEDLINE (1946 to May week 5, 2013), EMBASE (1991 to June 2013), CINAHL (1981 to June 2013), AMED (1985 to February 2012), LILACS (1981 to June 2013), Web of Science (1955 to June 2013), CAMBASE (no time limits), the Centre for Complementary Medicine Research (1988 to September 2007), WHO ICTRP and clinicaltrials.gov (last searched 5 June 2013), screened references and asked experts in the field about published and unpublished studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing mono‐preparations of Echinacea with placebo.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently assessed eligibility and trial quality and extracted data. The primary efficacy outcome was the number of individuals with at least one cold in prevention trials and the duration of colds in treatment trials. For all included trials the primary safety and acceptability outcome was the number of participants dropping out due to adverse events. We assessed trial quality using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool.

Main results

Twenty‐four double‐blind trials with 4631 participants including a total of 33 comparisons of Echinacea preparations and placebo met the inclusion criteria. A variety of different Echinacea preparations based on different species and parts of plant were used. Evidence from seven trials was available for preparations based on the aerial parts of Echinacea purpurea.

Ten trials were considered to have a low risk of bias, six to have an unclear risk of bias and eight to have a high risk of bias. Ten trials with 13 comparisons investigated prevention and 15 trials with 20 comparisons investigated treatment of colds (one trial addressed both prevention and treatment).

Due to the strong clinical heterogeneity of the studies we refrained from pooling for the main analysis. None of the 12 prevention comparisons reporting the number of patients with at least one cold episode found a statistically significant difference. However a post hoc pooling of their results, suggests a relative risk reduction of 10% to 20%. Of the six treatment trials reporting data on the duration of colds, only two showed a significant effect of Echinacea over placebo. The number of patients dropping out or reporting adverse effects did not differ significantly between treatment and control groups in prevention and treatment trials. However, in prevention trials there was a trend towards a larger number of patients dropping out due to adverse events in the treatment groups.

Authors' conclusions

Echinacea products have not here been shown to provide benefits for treating colds, although, it is possible there is a weak benefit from some Echinacea products: the results of individual prophylaxis trials consistently show positive (if non‐significant) trends, although potential effects are of questionable clinical relevance.

Plain language summary

Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold

Preparations of the plant Echinacea are widely used in some European countries and in North America for common colds. Echinacea preparations available on the market differ greatly as different types (species) and parts (herb, root or both) of the plant are used, different manufacturing methods (drying, alcoholic extraction or pressing out the juice from fresh plants) are used and sometimes also other herbs are added.

We reviewed 24 controlled clinical trials with 4631 participants investigating the effectiveness of several different Echinacea preparations for preventing and treating common colds or induced rhinovirus infections. Our review shows that a variety of products prepared from different Echinacea species, different plant parts and in a different form have been compared to placebo in randomized trials. Due to the significant differences in the preparations tested, it was difficult to draw strong conclusions. Five trials were rated as having a low risk of bias in all five categories of the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. Five more trials were rated as low risk of bias, having an unclear risk of bias in only one category. Eight trials were rated as having a high risk of bias in at least one category and the remaining six as having an unclear risk of bias.

The majority of trials investigated whether taking Echinacea preparations after the onset of cold symptoms shortens the duration, compared with placebo. Although it seems possible that some Echinacea products are more effective than a placebo for treating colds, the overall evidence for clinically relevant treatment effects is weak. In general, trials investigating Echinacea for preventing colds did not show statistically significant reductions in illness occurrence. However, nearly all prevention trials pointed in the direction of small preventive effects. The number of patients dropping out or reporting adverse effects did not differ significantly between treatment and control groups in prevention and treatment trials. However, in prevention trials there was a trend towards a larger number of patients dropping out due to adverse events in the treatment groups.

The evidence is current to July 2013.

Background

Description of the condition

Common cold is the most frequent disease in humans. A large US‐American survey showed that over 70% of the population annually was suffering from at least one viral respiratory tract infection. The authors concluded that the economic burden in the USA was almost USD 40 billion annually (Fendrick 2003). Viral agents causing common colds are mostly picornaviruses (rhinoviruses and enteroviruses), coronaviruses, adenoviruses, parainfluenza viruses and respiratory syncytial viruses (Denny 1995; Monto 1987). The incidence of the common cold has a peak in the winter months. There are several different hypotheses and explanations for this. One is that cooling of the nasal airway decreases the effectiveness of local respiratory defenses such as mucociliary clearance and leucocyte phagocytosis (Eccles 2002).

Description of the intervention

Extracts of the plant Echinacea (of the family Asteraceae) are widely used by consumers and practitioners in some European countries and in the US for preventing and treating upper respiratory tract infections (Barrett 2003). In the US mainstream market, Echinacea preparations are among the second top‐selling herbal products (Blumenthal 2005).

Assessment of the effectiveness of Echinacea preparations is complicated by the limited comparability of the available preparations for the following reasons.

Three different species are in medical use: Echinacea purpurea (E. purpurea),Echinacea pallida (E. pallida) and Echinacea angustifolia (E. angustifolia).

Different parts of the plant are used (root, herb, flower or whole plant).

Different methods of extraction are used.

In some preparations other plant extracts or homeopathic components are added.

The evidence available from clinical trials on its effectiveness has been considered inconsistent in several reviews (Barrett 1999; Caruso 2005; Linde 2006; Melchart 1994; Melchart 1999). Two meta‐analyses pooling trials using different heterogeneous Echinacea preparations for the treatment of induced rhinovirus infections (Schoop 2006b) or the common cold (Shah 2007) found more positive results for the effect of Echinacea. These results have to be interpreted with caution, as the great heterogeneity of tested Echinacea preparations makes comparison and pooling of data methodologically questionable.

How the intervention might work

The exact mechanisms of action for the immunomodulating effects of Echinacea preparations are unclear. Four classes of compounds are known to contribute to the immunomodulatory activity of Echinacea extracts: alkamides, glycoproteins, polysaccharides and caffeic acid derivatives (CADs). Phenolic compounds include caffeic, cichoric, caftaric and chlorogenic acid, as well as cynarin and echinacoside and are found in differing concentrations in the roots of both E. angustifolia and E. purpurea but also in the aerial parts of E. purpurea. Alkamides (alkylamides; fatty acid amides) are characteristic constituents of E. angustifolia roots, but are also found in roots and aerial parts of E. purpurea. Flavonoids, essential oils, polyacetylenes, ketones and pyrrolizidine alkaloids have also been isolated from Echinacea species. It is important to note that the pharmacologic effects associated with the constituents of Echinacea may result from independent or synergistic interactions with single or multiple constituents.

E. purpurea extracts rich in glycoproteins, polysaccharides and CADs have long been reported to demonstrate immunoactivity. Research in mice more than two decades ago demonstrated activation of macrophages and natural killer cells (Bauer 1989). Since then, numerous studies have supported these findings and have reported a variety of additional effects on adaptive and innate immune mechanisms (Chavez 2007; Gurbuz 2010; Hall 2007; Ramasahayam 2011; Ritchie 2011; Sadigh‐Eteghad 2011; Yamada 2011; Zhai 2007).

In contrast, early research on alkamide‐rich extracts of E. angustifolia and E. purpurea suggested anti‐inflammatory activity (Müller‐Jakic 1994). Since then, however, studies have reported immunoactivity attributable to alkamides (Lalone 2009; Matthias 2008) and have suggested that influences on inflammatory pathways are complex, with both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory effects reported (Birt 2008; Qiang 2013; Yu 2013). Echinacea alkamides have been shown to be absorbed into the blood (Matthias 2005; Woelkart 2005b; Woelkart 2006; Woelkart 2008) and appear to exert a variety of effects through the endocannabinoid system (Chicca 2009; Woelkart 2005a; Woelkart 2007). Research on the effects of gene expression and signaling pathways is well underway (Altamirano‐Dimas 2007; Gertsch 2004; Uluisik 2012).

In addition to research on immune and inflammatory pathways, indications of antiviral activity have been reported (Bodinet 2002; Ghaemi 2009; Sharma 2006). Finally, recent research suggests potential anti‐anxiety properties (Haller 2013), potentially due to neuro‐synaptic modulation in the hippocampus (Hajos 2012).

In summary, while it is clear that variousEchinacea extracts and constituents have demonstrated pharmacological activities in a variety of biological assays, there is as yet no evidence‐based conceptual framework to explain howEchinacea might effectively prevent or treat acute respiratory infections.

Why it is important to do this review

The common cold has a high prevalence and although it is a self limiting condition effective treatment options which lessen the severity and duration of symptoms would be of major importance. Echinacea products are widely used but their effectiveness is uncertain. We completed a first version of this review in 1998 (Melchart 1999), updated it in 2006 (Linde 2006) and again in 2008 (Linde 2008). The last literature search was conducted in 2007 and did not detect new publications on the issue. Now, six years later, several new trials have been published and evidence may have changed. Therefore, a major update of this review was necessary.

Objectives

To assess whether there is evidence that Echinacea preparations are effective and safe compared to placebo in the prevention and treatment of the common cold.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

We included studies if participants were:

individuals with non‐specific viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) with a clinical diagnoses of common cold, influenza‐like syndrome or viral URTI (it was not possible to apply a standard definition of common cold across all trials);

volunteers without acute URTIs but treated for preventative purposes (prevention studies);

volunteers without acute URTIs but challenged with rhinovirus treated for preventative or therapeutic purposes (or both).

We did not include studies of individuals suffering from other URTIs with a defined etiology (for example influenza) or a more specific symptomatology (for example acute sinusitis, angina tonsillaris).

Types of interventions

We included trials of oral Echinacea mono‐preparations versus placebo. We excluded trials on combinations of Echinacea and other herbs and trials comparing Echinacea with no treatment or another treatment than placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Selected trials had to include clinical outcome measures related to occurrence (prevention studies) and severity or duration of infections (prevention and treatment studies). We excluded trials focusing solely on physiological parameters (such as phagocytosis activity). We did not include or exclude studies based on their primary outcome measure if at least one clinically relevant outcome measure listed above was reported.

Primary outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome measure for prevention trials was the number of participants experiencing at least one cold episode.

The primary efficacy outcome measure for treatment trials was duration in days.

The primary outcome for safety and acceptability for both prevention and treatment trials was the number of participants dropping out due to side effects or adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary efficacy outcome measures for prevention trials were the number of participants experiencing more than one cold episode; cold duration in days; severity scores.

Secondary efficacy outcome measures for treatment trials were total severity and duration measures (e.g. area under the curve); severity of symptoms at days two to four and at days 5 to 10; in trials with very early onset of treatment also the number of participants who developed the 'full picture of a cold'.

Secondary safety and acceptability outcome measures for both prevention and treatment trials were the total number of drop‐outs and the number of participants reporting side effects or adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this 2013 update we searched for new studies published since the last publication of our review and also searched for older trials. This was done as search methods have evolved over time and the inclusion criteria of our reviews have changed considerably.

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 5, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 5 June 2013) which contains the Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialized Register, MEDLINE (1946 to May week 4, 2013), EMBASE (1991 to June 2013), CINAHL (1981 to June 2013), AMED (1985 to February 2012), LILACS (1981 to June 2013) and Web of Science (1955 to June 2013).

We used the following search strategy to search CENTRAL and MEDLINE. We combined the MEDLINE search strategy with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐maximizing version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011).

MEDLINE (Ovid)

1 Echinacea/ 2 echinac*.tw. 3 coneflower*.tw. 4 ("E. purpurea" or "E. angustifolia" or "E. pallida").tw. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

We adapted the search strategy to search EMBASE (Appendix 1), CINAHL (Appendix 2), AMED (Appendix 3), LILACS (Appendix 4) and Web of Science (Appendix 5). Searches for the first review (published in 1999) and the 2007 update are described in Appendix 6.

Searching other resources

We searched WHO ICTRP and clinicaltrials.gov (latest search 8 October 2012), the Centre for Complementary Medicine Research (1988 to September 2007) and CAMBASE (latest search 5 June 2013). We screened bibliographies of identified trials and review articles for further potentially relevant publications. We contacted experts in the field and asked about further published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (MKV) screened the titles and abstracts, where available, of all identified references and eliminated non‐human studies and trials without a control group. We obtained and checked further copies of all other references for eligibility. At least two review authors independently checked all potentially relevant publications or reports identified by the screening process for fulfillment of the selection criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We assessed eligibility of trials in which one of the review authors was involved by review authors not involved in the trial.

Data extraction and management

At least two authors independently extracted descriptive information on patients, interventions, outcomes, results, drop‐outs and side effects using a standard data extraction form. Details on extraction of outcomes used for analyses are described below. Trials in which review authors were involved were extracted and assessed by review authors not involved in the trial. We contacted trial authors or manufacturers and sponsors and asked them to provide lacking or additional data if the information in the available publications or reports was incomplete. A pharmacist with specific expertise on Echinacea (KAW) extracted information on the Echinacea preparations.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included trials using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011b). We assessed the generation of the random sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. For an overall assessment we considered as low risk of bias only trials in which at least four of the five items were rated as low risk and none high risk. Any trial with one or more items rated as high risk was considered high risk in the overall assessment. The remaining trials were considered as unclear risk.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous efficacy outcomes we calculated risk ratios (RR) and for safety/adverse event outcomes we calculated odds ratios (OR). For continuous efficacy outcomes we calculated mean differences (MD) if the same scale of measure was used (e.g. number of days) and standardized MD if measurement tools or scales varied. For all effect estimates we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

In all trials individual patients were randomized. However, in one trial (Taylor 2003) investigating early self treatment more than one cold could be treated by participants (on average participants treated about 1.5 cold episodes) and the results for duration and severity presented in the publication were based on the number of cold episodes. For effect size calculation we used the number of cold episodes, because using the number of patients would only lead to a small change of the weight of this trial.

Dealing with missing data

In case of missing outcome data we tried to obtain additional information from study authors. If, in case of continuous outcomes, means were presented but standard deviations were missing we calculated standard deviations from standard errors, P values or confidence intervals as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Section 7.7.3 (Higgins 2011a). In case of missing dichotomous data we assumed that no event occurred.

Data synthesis

We expected a priori that meaningful quantitative meta‐analyses of the studies would not be possible for the following reasons: 1) a variety of Echinacea preparations are used in trials (phytochemical comparability is unclear); 2) the approach of studies differs (some investigate prevention, some self treatment, some treatment, some treatment and/or prevention of experimentally induced colds); 3) outcome measures differ in the trials; and 4) the presentation of results in available reports often includes insufficient detail to allow effect size estimation. However, we aimed to calculate effect size estimates for relevant outcome measures in single trials whenever possible. If an outcome was probably measured but data for effect size calculation were not reported we documented this.

For our main analysis we had predefined criteria to consider pooling (fixed‐effect model) of data from different trials: 1) treatment given for the same purpose (prevention or treatment); 2) use of the same or a very similar (regarding plant species, part and extraction mode) preparation and in similar dosage; and 3) at least two trials that met the criteria 1 and 2. Because of these criteria we ended up with multiple subgroups and most subgroups consisted of only one trial (with a maximum of two trials when criteria were met for pooling) we decided to run additional exploratory random‐effects meta‐analyses including all available trials regardless of the type of Echinacea product tested. For these meta‐analyses studies with more than one Echinacea group were entered only once (pooling data from the Echinacea groups) to avoid duplicate use of placebo data. The meta‐analyses serve to provide a crude overview of the overall direction and magnitude of the available study results and to investigate consistency and heterogeneity of the findings. We considered pooled effect sizes as clinically interpretable – at least with caution – when a) at least two‐thirds of trials measuring an outcome actually could be included in the meta‐analysis; b) at least five trials could be pooled; c) the I² statistic was ≤ 40%; and d) the P value of the Chi² test for heterogeneity was ≥ 0.25. All other pooled effect sizes were not considered clinically interpretable and only used to check whether results differed between studies.

Duration of colds was analyzed and reported in highly variable manner in the primary studies. While only two presented MD with some measure of variability (the measure we would have preferred for meta‐analysis), some provided median duration and P values from log rank text, Cox regression or a Wilcoxon rank sum test. According to our protocol we included only the two trials reporting mean duration. To provide at least a crude summary of study findings in a post hoc secondary analysis we used an overall estimate of effect for each study rather than summary data for each intervention group for an inverse variance analysis. For this exploratory analysis we interpreted medians as means for calculating the MD and calculated standard errors as if P values were derived from a t‐test. We did not pool findings from individual studies due these liberal assumptions and the heterogeneity of the study findings but included the resulting forest plot only for giving a graphical impression of the overall evidence.

In general we used the number of patients randomized when calculating effect estimates for dichotomous outcome and the number of patients analyzed for continuous measures. However, for some study approaches this was considered inappropriate. For example, in five trials of self treatment, participants were randomized to receive an Echinacea product or placebo medication to take at home but told to take their medication only in case a cold occurred. In these cases we used the number of patients in whom a cold actually occurred for analyses.

In the case of pooling we examined heterogeneity between trials by calculating a Chi² test, the I² statistic and the Tau² statistic. An I² statistic value of 0% to 40% was not considered to be important heterogeneity; 40% to 60% was considered moderate heterogeneity; 60% to 90% was considered substantial and an I2 statistic value greater than 90% indicated considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We generated funnel plots for meta‐analyses including at least four studies. We carried out all calculations in RevMan 2012, version 5.2.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

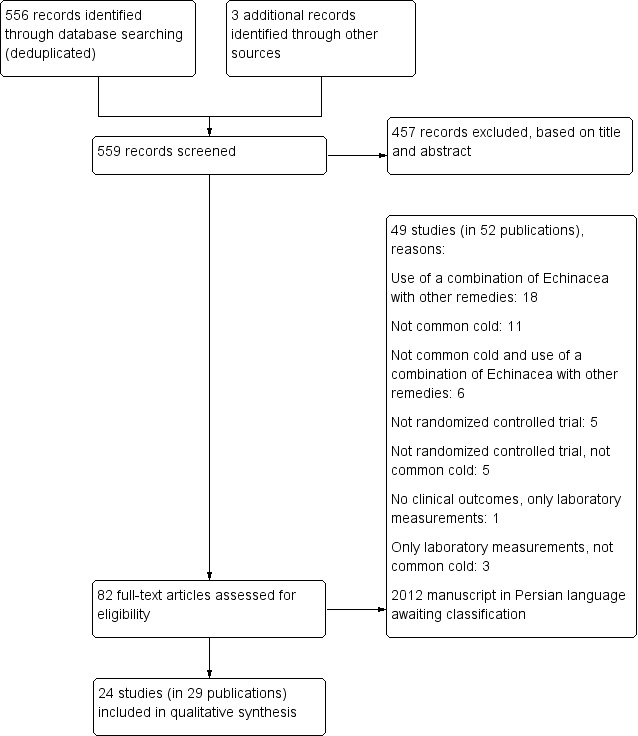

The database searches identified a total of 556 hits (Figure 1). Three additional records were identified through other sources. We identified a total of 82 full‐text articles describing trials which tested preparations of Echinacea in humans (alone or in combination with other plant extracts).

1.

study flow diagram.

Included studies

Twenty‐four studies (in 29 publications) met the inclusion criteria (Characteristics of included studies table). Of these, 15 had been included in the previous version of the review (Barrett 2002; Brinkeborn 1999; Bräunig 1992; Dorn 1997; Galea 1996; Goel 2004; Goel 2005; Grimm 1999; Hoheisel 1997; Kim 2002a; Lindenmuth 2000; Melchart 1998; Schulten 2001; Taylor 2003; Yale 2004), two of the now included studies on induced colds had initially been excluded in the previous version of the review (Sperber 2004; Turner 2000) and seven studies have been newly included (Barrett 2010; Hall 2007; Jawad 2012; O'Neill 2008; Tiralongo 2012; Turner 2005; Zhang 2003). One study (Taylor 2003) was in children, the other 23 in adults. Three trials (Brinkeborn 1999; Bräunig 1992; Melchart 1998; Turner 2005) had more than one experimental group receiving an Echinacea product (different dosage in one and different extracts in three) so there were a total of 33 comparisons of an Echinacea preparation with placebo. One study had both a placebo and a no treatment control group (Kim 2002a) and one study had a no treatment and an unblinded Echinacea group in addition to the blinded Echinacea and placebo groups (Barrett 2010).

Twelve trials originated from the USA, five from Germany, three from Canada, two from Sweden, one from the United Kingdom and one from Australia. Two trials from the USA and one from Canada were only available as unpublished manuscripts (Galea 1996; Kim 2002a; Zhang 2003).

Excluded studies

Forty‐nine studies (in 53 publications) did not meet the inclusion criteria (Characteristics of excluded studies table; Figure 1). In 19 studies Echinacea in combination with other remedies was used. Eleven studies examined other conditions than common cold. Six studies examined other conditions than common cold using Echinacea in combination with other remedies. Ten studies were not randomized controlled trials, five of which also examined other conditions than common cold. Four studies only examined laboratory measurement results, without clinical outcomes and three of them examined other conditions than common cold.

Among the 49 excluded studies there was one which was included in the previous version of this review (Spasov 2004). It was an unblinded study without placebo control.

Study approaches

As described in the methods section, we separated prevention trials (treatment of healthy volunteers without cold symptoms to avoid occurrence of colds or reduce severity and duration of occurring cold) and treatment trials (treatment of individuals with colds or of early cold symptoms).

Ten studies were prevention trials (with a total of 13 Echinacea groups). In four of these trials 431 healthy volunteers (Hall 2007) or persons being challenged by inoculation with rhinovirus (Sperber 2004; Turner 2000; Turner 2005) were treated over a shorter period (two to four weeks). Six trials including 1391 participants (Grimm 1999; Jawad 2012; Melchart 1998; O'Neill 2008; Tiralongo 2012; Zhang 2003) treated healthy volunteers over a longer period (6 to 16 weeks) for preventative purposes.

Fifteen studies (with 20 comparisons) were categorized as treatment trials, but among these studies two different approaches were used: five placebo‐controlled trials with a total of seven Echinacea groups (Brinkeborn 1999; Galea 1996; Goel 2004; Goel 2005; Taylor 2003) investigated self treatment. Healthy volunteers were randomized and instructed to start treatment only if they caught a cold. These trials randomized a total of 1910 participants (range 150 to 559). However, 846 did not start treatment as they did not catch a cold during the study period; therefore only 1064 (62 to 436) actually started treatment. In 10 trials with a total of 13 Echinacea groups (Barrett 2002; Barrett 2010; Bräunig 1992; Dorn 1997; Hoheisel 1997; Kim 2002a; Lindenmuth 2000; Schulten 2001; Turner 2005; Yale 2004) individuals with cold symptoms were randomized and treated. These 10 trials included a total of 1538 participants (range 57 to 359 in each). Typically, they tried to start treatment as early as possible. Three trials (Hoheisel 1997; Schulten 2001; Turner 2005) explicitly not only investigated duration and severity of symptoms but also tried to prevent the development of a 'full cold' by treatment of first symptoms. Two of these trials were performed in industrial plants where employees could access treatment very fast (Hoheisel 1997; Schulten 2001). Development of a "full cold" was also tested by one trial examining experimental rhinovirus colds (Turner 2005).

Echinacea preparations tested

In the 33 experimental groups of the 24 included trials, widely different Echinacea preparations were used (Table 1). A large proportion of the preparations used in the trials were pressed juices (stabilized with alcohol), alcohol tinctures or tablets made from dried extracts. In six trials preparations from the pressed juice of the aerial parts of E. purpurea were used (Grimm 1999; Hoheisel 1997; Schulten 2001; Sperber 2004Taylor 2003; Yale 2004). In five of these six trials (Grimm 1999; Hoheisel 1997; Schulten 2001; Sperber 2004; Taylor 2003) the same product was used. Preparations based on E. purpurea root alone were used in two trials, with three experimental groups (Bräunig 1992; Zhang 2003). An identical product based on a mixture of E. purpurea root (5%) and herb (95%) was used in two trials with three experimental groups (Brinkeborn 1999; Jawad 2012). One of these trials (Brinkeborn 1999) tested two different concentrations of the same product. Two trials by the same study group (Goel 2004; Goel 2005) investigated the effectiveness of an extract of 'various' parts of E. purpurea. The particular aspect of this preparation was that it was standardized for its content of three bioactive components (alkamides, cichoric acid and polysaccharides).

1. Details of the preparations used in the included trials.

| Reference | Preparation | Manufacturer | Species, part | Extraction | Content details | Galenic form | Dosage | Treatment period | Remarks |

| Barrett 2002 | Not reported | Shaklee Tecninca, Pleasanton, California | Unrefined E. ang. root (50%), E. purp. herb (25%) and root (25%) | Not applicable (dried Echinacea) | 0.20% to 0.26% echinacoside, 0.77% to 0.84% dichroic acid, 0.82% alkamides, 0.03% chlorogenic acid, 0.33% cafeolytartaric acid | Capsules | 6 x 4 capsules (6 g) during first 24 hours, then 3 x 4 capsules (3 g/day) | 10 days | — |

| Barrett 2010 |

Not reported | MediHerb, Warwick, Queensland, Australia | E. purp. root, E.ang. root | Not reported | 2.1 mg of alkamides per tablet | Tablets | 4 x 2 tablet during first 24 hours, then 4 x 1 tablet per day for the next 4 days; that means 10.2 g of dried Echinacea root during first 24 hours, 5.1 g during each of the next days | 5 days | — |

| Brinkeborn 1999, Group 1 | Echinaforce | Bioforce, Roggwil, Switzerland | E. purp. herb (95%) and root (5%) | Alcoholic aqueous extract | 6.78 mg crude extract | Tablets | 2 x 3 (40.68 mg/day) | Max. 7 days | — |

| Brinkeborn 1999, Group 2 | No brand name | Bioforce, Roggwil, Switzerland | E. purp. herb (95%) and root (5%) | Alcoholic aqueous extract | 48.27 mg crude extract | Tablets | 2 x 3 (289.62 mg/day) | Max. 7 days | — |

| Brinkeborn 1999, Group 3 | No brand name | Bioforce, Roggwil, Switzerland | E. purp. root | Alcoholic aqueous extract | 29.60 mg crude extract | Tablets | 2 x 3 (177.6 mg/day) | Max. 7 days | — |

| Bräunig 1992, group 1 | Not reported | Not reported | E. purp. root | 55% v/v ethanolic extract, DER 1:5 | Not reported | Tincture | 180 drops (900 mg/day) | Probably 8 to 10 days | — |

| Bräunig 1992, group 2 | Not reported | Not reported | E. purp. root | 55% v/v ethanolic extract, DER 1:5 | Not reported | Tincture | 90 drops (450 mg/day) | Probably 8 to 10 days | — |

| Dorn 1997 | Not reported | Not reported | E. pallida root | Not reported | Not reported | Tincture | 90 drops (900 mg/day) | 8 to 10 days | — |

| Galea (unpublished) | Not reported | Local pharmacist | E. ang. (part not specified) | Not reported | Powder standardized at 4% content of echinacoside | Capsules | 3 x 1 (750 mg/day) | 10 days | — |

| Goel 2004 | Echinilin | Natural Factors Nutritional Products, Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada | E. purp. (various parts) | Aqueous and alcoholic extract combined to a 40% ethanolic formulation | Standardized for 0.25 mg/ml alkamides, 2.5 mg/ml cichoric acid, 25 mg/ml polysaccharides | Liquid | 10 x 4 ml day 1, then 6 days 4 x 4 ml | 7 days | Extract standardized on the basis of 3 known active components |

| Goel 2005 | Echinilin | Natural Factors Nutritional Products, Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada | E. purp. (various parts) | Aqueous and alcoholic extract combined to a 40% ethanolic formulation | Standardized for 0.25 mg/ml alkamides, 2.5 mg/ml cichoric acid, 25 mg/ml polysaccharides | Liquid | 8 x 5 ml day 1, then 6 days 3 x 5 ml | 7 days | Extract standardized on the basis of 3 known active components |

| Grimm 1999 | Echinacin | Madaus AG, Cologne, Germany | E. purp. aerial parts | Fresh expressed juice of whole flowering plants harvested without roots, containing 22% alcohol | Not reported | Liquid | 2 x 4 ml day | 8 weeks | — |

| Hall 2007 | Echinacea Standardized | Nature´s Way, Springville, UT (USA) | E. purp. (part not specified) | Not reported | Not reported | Capsules | 8 capsules/day (3 x 2 with each meal and 2 at bedtime) | 4 weeks | — |

| Hoheisel 1997 | Echinagard (Echinacin) | Madaus AG, Cologne, Germany | E. purp. aerial parts | Fresh expressed juice of whole flowering plants harvested without roots, stabilized with 20% ethanol | Not reported | Liquid | 20 drops every 2 hours day 1, then 3 x 20 drops/day | Max. 10 days | — |

| Jawad 2012 | Echinaforce drops | A. Vogel, Bioforce, Switzerland | E. purp. (95% herb, 5% roots) | Alcohol (57%) extract from freshly harvested E. purp. | 5 mg/100g of dodecatetraenoic acid isobutylamide | Liquid | 3 x 0.9 ml/day (2400 mg of extract/day); in case of cold: 5 x 0.9ml/day (4000 mg of extract/day) | 4 months | Each single dose was diluted in water and retained in mouth for 10 seconds |

| Kim (unpublished) | Not reported | Nature's Way products, Inc. R/O America's Natural healthcare Company, Springville, Utah | E. purp. herb (80%), E. ang. roots (20%) | No detailed information; final tincture with 25% to 35% alcohol | Not reported | Liquid | 101 ml (1000 mg dry plant) per day | At least 5 days | — |

| Lindenmuth 2000 |

Echinacea Plus herbal tea | Dry extract ingredient by Emil Flachsmann AG, Zurich, Switzerland | E. purp. and E. ang. aerial parts; E. purp. roots | E. purp. root water soluble dry extract DER 6:1 | 1.275 mg per tea bag serving | Tea bag | 5 to 6 cups day 1, titration to one cup on day 5 | 5 days | — |

| Melchart 1998 Group 1 | No brand name | Plantapharmazie, Göttingen, Germany | E. ang. root | 30% ethanolic extract, DER 1:11 | Extract contained 1007.9 µg/ml glycoproteins/polysaccharides and echinacoside | Tincture | 2 x 50 drops | 12 weeks (intake on 5 days per week) | — |

| Melchart 1998 Group 2 | No brand name | Plantapharmazie, Göttingen, Germany | E. purp. root | 30% ethanolic extract, DER 1:11 | Extract contained 1026.2 µg/ml glycoproteins/polysaccharides and cichoric acid | Tincture | 2 x 50 drops | 12 weeks (intake on 5 days per week) | — |

| O'Neil 2008 | No brand name | Natures Resource, Mission Hill, California | E. purp. (part not specified) | Not reported | Not reported | Capsules | 3 x 2 capsules/day (1 capsule containing 300 mg E. purp.) | 8 weeks | — |

| Schulten 2001 | Echinacin | Madaus AG, Cologne, Germany | E. purp. aerial parts | Fresh expressed juice of whole flowering plants harvested without roots, stabilized with 20% ethanol, DER 1.7‐2.5:1 | Not reported | Liquid | 2 x 5 ml/day | 10 days | — |

| Sperber 2004 | EchinaGuard | Madaus AG, Cologne, Germany | E. purp. aerial parts | Pressed juice in 22% alcohol base | Not reported | Liquid | 3 x 2.5 ml/day | 14 days | — |

| Taylor 2003 | Echinacin | Madaus AG, Cologne, Germany | E. purp. aerial parts | Pressed juice, combined with syrup | Not reported | Liquid (dried pressed juice dissolved in syrup) | 2 x 3.75 ml/day (children 2 to 5 years), 2 x 5 ml/day (6 to 11 years) | Max. 10 days | — |

| Tiralongo 2012 | MediHerb | Integria Healthcare Pty Ltd., Australia | E. purp. root, E. ang. root | Extract, details not reported | Tablets standardized for a content of 4.4 mg alkylamides with 112.5 mg E. purp. 6:1 extract and 150 mg E. ang. 4:1 extract (detailed alkamide composition is summarized in a table with e.g. a content of 1.504 mg/tablet dodecatetraenoic acid isobutyl amides) | Tablets | Priming dose 2 x 1 tablet/day, flying dose 2 x 2 tablets/day, overseas dose 2 x 1 tablet/day, after‐travel dose 2 x 1 tablet/day, sick dose 2 x 3 tablets/day | 35 days if 1 week of travel (14 days primary dose, 7 days overseas, 14 days after‐travel dose) or 63 days if 5 weeks of travel (11 days with priming dose, 10 days flying dose, 25 days overseas dose, 10 days flying dose and 7 days after travel dose) | — |

| Turner 2005 Group 1 and 4 | No brand name | Not reported | E. ang. root | Extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide | No polysaccharides, 73.8% alkamides, no echinacosides | Liquid | 3 x 1.5 ml/day (3 x equivalent of 300 mg Echinacea root) | 13 days (virus challenge on day 8) | — |

| Turner 2005 Group 2 and 5 | No brand name | Not reported | E. ang. root | Extraction with 60% ethanol | 48.9% polysaccharides, 2.3% alkamides, no echinacosides, 0.16 mg/ml cynarine) | Liquid | 3 x 1.5 ml/day (3 x equivalent of 300 mg Echinacea root) | 13 days (virus challenge on day 8) | — |

| Turner 2005 Group 3 and 6 | No brand name | Not reported | E. ang. root | Extraction with 20% ethanol | 42.1% polysaccharides, 0.1% alkamides, no echinacosides | Liquid | 3 x 1.5 ml/day (3 x equivalent of 300 mg Echinacea root) | 13 days (virus challenge on day 8) | — |

| Turner 2000 | No brand name | Not reported | E. purp. and E. ang. | 4% phenolic extract | 0.16% cichoric acid, almost no echinacosides or alkamides | Capsules with powder | 3 x 300 mg/day | 19 days (virus challenge on day 14) | — |

| Yale 2004 | EchinaFresh | Enzymatic Therapy, Green Bay, Wisconsin | E. purpurea aerial parts | Pressed juice | Standardized for a content of 2.4% soluble beta‐1,2‐D‐fructofuranosides | Capsules with freeze dried juice | 3 x 1 capsule/day | 7 days, if symptoms not resolved max. 14 days | — |

| Zhang 2003 | No brand name | Not reported | E. purp. root | Root powder | 4.4 mg cichoric acid | Capsules with 294 mg powder | 1 capsule/day | 8 weeks | — |

E. ang: Echinacea angustifolia E. pallida: Echinacea pallida E. purp: Echinacea purpurea v/v: volume/volume

The 14 remaining Echinacea preparations were only used in one trial each: tinctures or extracts prepared from E. pallida root (Dorn 1997), E. angustifolia root (Melchart 1998) or E. angustifolia, without information on the plant parts used (Galea 1996); a dried plant preparation based on 50% E. angustifolia root, 25% E. purpurea root and 25% E. purpurea herb (Barrett 2002); a preparation based on E. purpurea root and E. angustofolia root, without information on extraction details (Barrett 2010); a tincture from 80% E. purpurea herb and 20% E. angustifolia root (Kim 2002a); a preparation based on an extract of E. purpurea root and E. angustofolia root (extraction details not reported) (Tiralongo 2012); a 4% phenolic extract of E. purpurea and E. angustofolia (Turner 2000); three preparations based on E. angustofolia root using three different extraction methods (20% alcohol; 60% alcohol and CO2) (Turner 2005); two kinds of E. purpurea capsules (parts and extraction details not reported (Hall 2007; O'Neill 2008); and a tea preparation based on dry extracts from the aerial parts of E. purpurea and E. angustifolia (Lindenmuth 2000).

Outcome measurement

All 10 prevention trials investigated the occurrence of cold. Other outcomes, like the number of people with more than one cold episode, duration and severity scores were only measured in some of the prevention trials. Among the self treatment and treatment trials, methods for outcome measurements and the results actually presented varied greatly (there were differences regarding instruments used, timing of measurements, type of analysis and descriptive statistics).

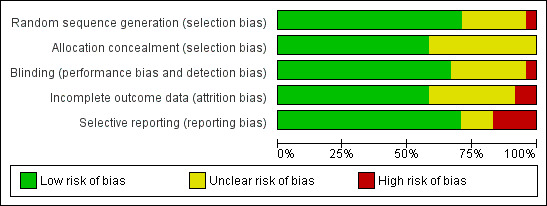

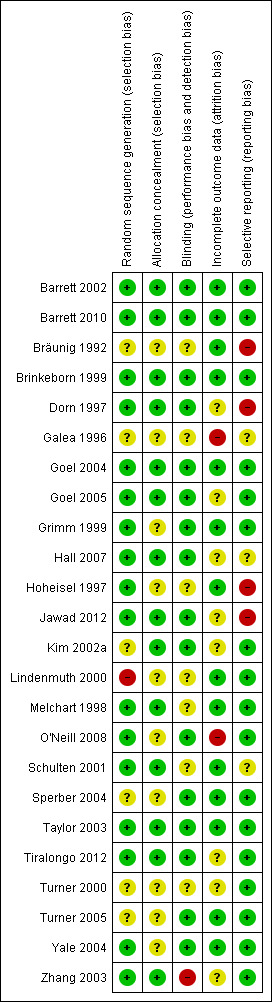

Risk of bias in included studies

'Risk of bias' judgements are given in the Characteristics of included studies table and in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We rated five trials (Barrett 2002; Barrett 2010; Brinkeborn 1999; Goel 2004; Taylor 2003) as having a low risk of bias in all five categories of the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011b). We rated five more trials as low risk of bias, having an unclear risk of bias in only one category. We rated eight trials as having a high risk of bias (Bräunig 1992; Dorn 1997; Galea 1996; Hoheisel 1997; Jawad 2012; Lindenmuth 2000; O'Neill 2008; Zhang 2003) and six as having an unclear risk of bias.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation was performed appropriately in at least 17 studies. Additional information by authors and sponsors was taken into account. In one study (Lindenmuth 2000), allocation to groups appeared to follow an alternating sequence rather than true randomization. However, the allocation process was handled by an independent and blinded secretary after inclusion of participants in the trial. This study was already included in the previous version of the review. An adequate method of concealment was used in at least 14 studies (taking into account additional information received from authors and sponsors). In 10 studies sufficiently detailed information on allocation concealment was not reported.

Blinding

All 24 trials were described as blinded. In 16 trials we considered the risk of performance and detection bias as low. One older trial was not adequately blinded (Bräunig 1992). In this three‐armed trial, one Echinacea group received 180 drops daily while the other Echinacea group and the placebo group received 90 drops. One trial was performed among employees of the manufacturer (Schulten 2001) who may have recognized the taste of their Echinacea product; the success of blinding was not tested. In one trial capsules filled with vegetable oil were used as placebo and may have been distinguishable from Echinacea capsules by taste (Galea 1996). In two more trials (Hoheisel 1997; Lindenmuth 2000) Echinacea preparation and placebo could possibly have been distinguishable by taste. Thirteen trials reported a test for the success of blinding. In 11 trials blinding seemed to have been successful while in two there was evidence of some unblinding (Melchart 1998) or major unblinding (Zhang 2003).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was considered low in 14 trials, having reported less than 20% attrition and performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis or reported generally less than 5% attrition. The risk of attrition bias was unclear in three and high in seven trials.

Selective reporting

We assessed 17 trials as having a low risk of reporting bias. In four trials important relevant outcomes are not reported/examined (Bräunig 1992; Hall 2007; Hoheisel 1997; Jawad 2012). In two trials the reports are not systematically biased, but outcomes have been reported insufficiently to allow effect size calculation (Galea 1996; Schulten 2001).

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes for prevention trials and for treatment or self treatment trials

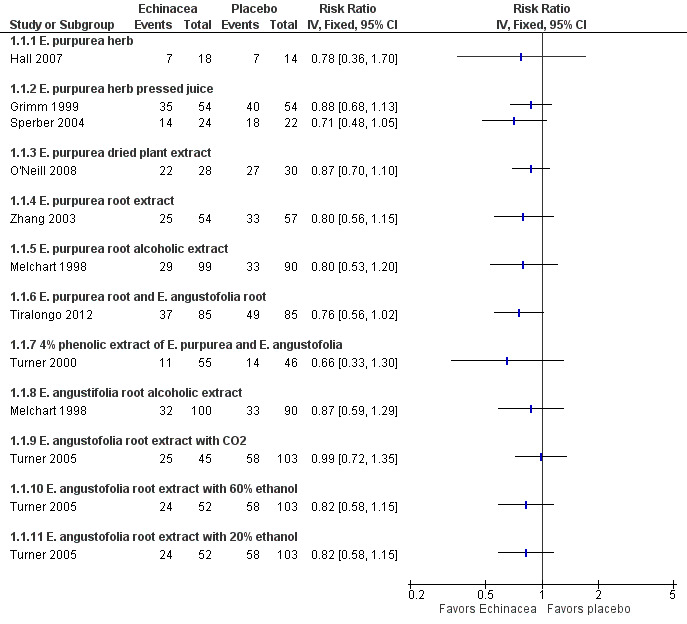

Primary efficacy outcome measure for prevention trials: number of participants experiencing at least one cold episode

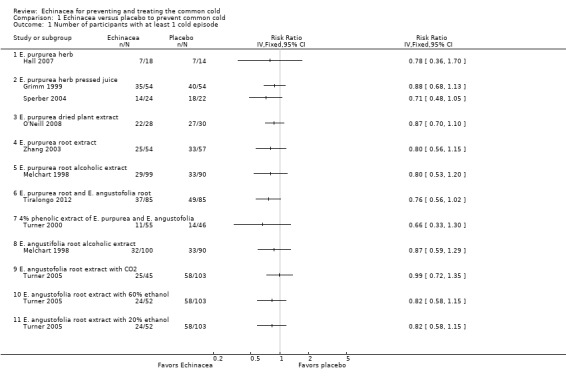

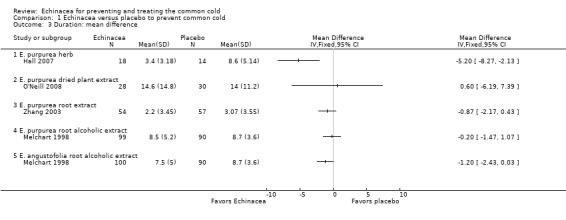

Nine of the 10 prevention trials reported the number of patients experiencing at least one cold. None of the 12 comparisons of Echinacea preparations and placebo in these nine trials (Grimm 1999; Hall 2007; Melchart 1998; O'Neill 2008; Sperber 2004; Tiralongo 2012; Turner 2000; Turner 2005; Zhang 2003) demonstrated statistically significant results in comparison to placebo (Figure 4; Analysis 1.1).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, outcome: 1.1 Number of participants with at least 1 cold episode.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 1 Number of participants with at least 1 cold episode.

Only two trials investigated the same Echinacea product; the pooled risk ratio (RR) also did not show significant effects over placebo (RR 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67 to 1.02; P = 0.07). However, in our exploratory meta‐analysis pooling all trials (1167 patients totally), regardless of the product used, prophylactic treatment with Echinacea products was associated with a reduced risk of experiencing a cold (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.92; P < 0.001). Study findings were highly consistent across studies with an I² statistic of 0%, a Tau² of 0.00 and a P value of 0.98 in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. The funnel plot showed some asymmetry (Eggers test p = 0.03) but point estimates in the single trials were similar and including only the four most precise trials in meta‐analysis reduced the pooled estimate only marginally (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.96). We could not include the largest prevention study (Jawad 2012) in the quantitative analyses as it did not report the number of patients with at least one cold but only the total number of cold episodes. There were 149 cold episodes in the Echinacea group versus 188 in the placebo group; this finding seems very compatible with the reduced RR suggested by our meta‐analysis.

The observed risk ratio of 0.83 in our meta‐analysis corresponds to an absolute risk reduction of 10% (95% CI 5% to 16%) and a number needed to treat of 10 (95% CI 6 to 20). As more participants in the control groups experienced a cold the absolute risk reduction in the four most precise trials was 11% (94% CI 4% to 19%) and the number needed to treat 9 (95% CI 5 to 25) in spite of the slightly larger risk ratio of 0.85.

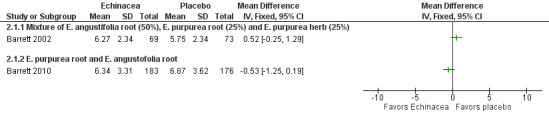

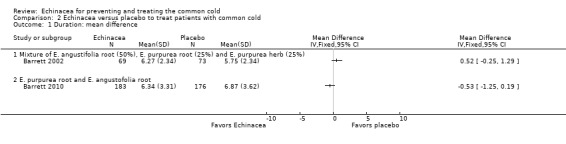

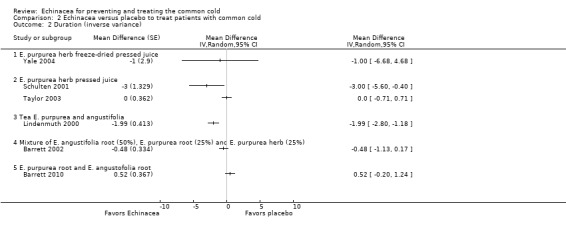

Primary efficacy outcome measure for treatment or self treatment trials: duration in days

Only one trial of a mixture of 50% E. angustifolia root, 25% E. purpurea root and 25% E. purpurea herb (Barrett 2002) and one trial of a mixture of E. purpurea root and E. angustifolia root (Barrett 2010) reported the mean duration of colds (Figure 5; Analysis 2.1). Neither trial found a significant difference compared to placebo. A total of six trials could be included in our post hoc secondary inverse variance analysis also using other data on duration (Analysis 2.2). Study findings were heterogeneous (I² statistic = 77%, Tau² = 0.88, P = 0.0002 in Chi² test) with two trials (Lindenmuth 2000; Schulten 2001) finding a significantly shorter duration in the Echinacea group.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, outcome: 2.1 Duration: mean difference.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 1 Duration: mean difference.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 2 Duration (inverse variance).

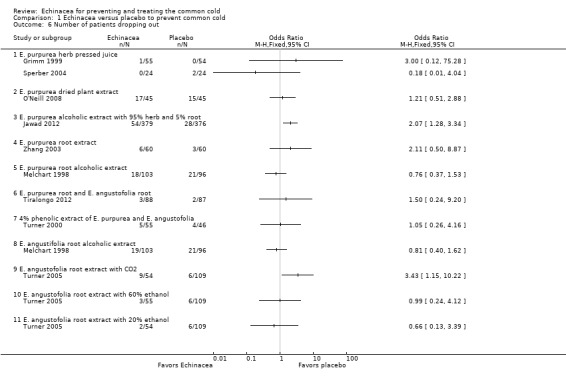

Primary safety and acceptability outcome for prevention trials: number of participants dropping out due to side effects or adverse events

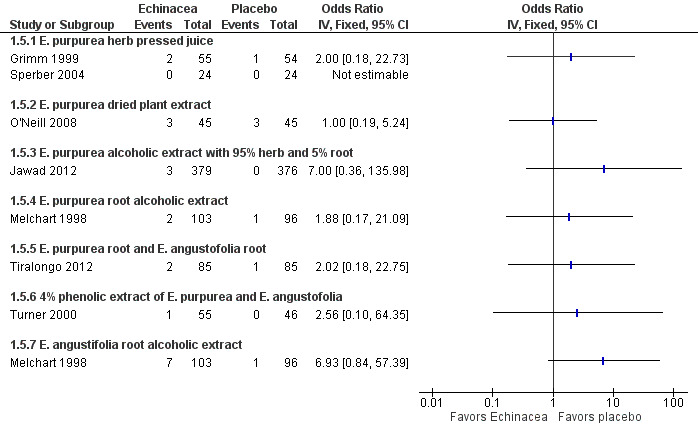

Our main outcome measure for the safety and acceptability analysis, the number of patients dropping out due to adverse effects, was reported in eight comparisons in seven studies (Grimm 1999; Jawad 2012; Melchart 1998; O'Neill 2008; Sperber 2004; Tiralongo 2012; Turner 2000; see Figure 6; Analysis 1.5). There were no significant differences in the single trials but the confidence intervals are wide as the number of patients dropping out was generally low. If study findings were pooled regardless of the Echinacea product used (heterogeneity indicators I² statistic = 0%; Tau² = 0.00; P = 0.87 in Chi² test) 2.4% in Echinacea groups dropped out from the studies due to side effects compared to 0.8% from the placebo groups (odds ratio (OR) 2.17, 95% CI 0.85 to 5.53; P = 0.10).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, outcome: 1.5 Number of patients dropping out due to adverse effects.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 5 Number of patients dropping out due to adverse effects.

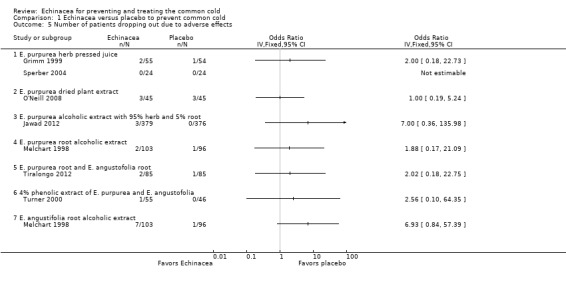

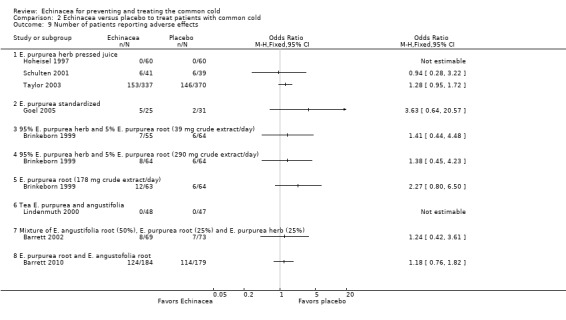

Primary safety and acceptability outcome for treatment or self treatment trials: number of participants dropping out due to side effects or adverse events

For 11 trials (14 comparisons) the number of patients dropping out due to side or adverse effects could be extracted. Only three of 1088 patients who received an Echinacea product and none of the 930 patients who received placebo dropped out for these reasons (Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 7 Number of patients dropping out due to adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes for prevention trials and for treatment or self treatment trials

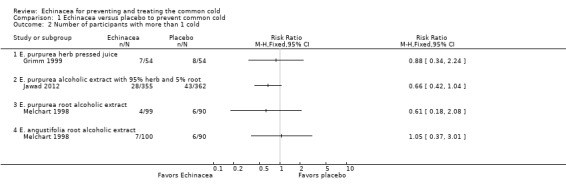

Secondary efficacy outcome measures for prevention trials: number of participants experiencing more than one cold episode; cold duration in days; severity scores

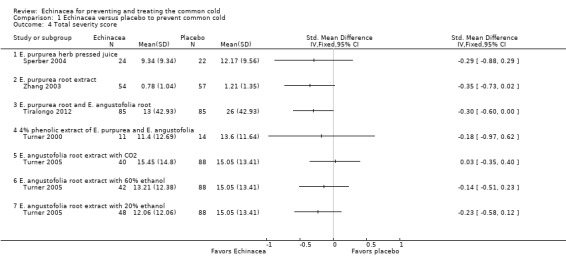

Three trials (with four comparisons) reported the number of patients with more than one cold episode (Analysis 1.2). None of the trials found significant differences but confidence intervals were very wide. Four trials (with five comparisons) reported the duration of cold episode (Analysis 1.3). Only one small trial (Hall 2007) found a very large (5.2 days on average) statistically significant effect over placebo. Point estimates in the other comparisons vary between 1.2 days shorter to 0.6 days longer duration in the Echinacea groups. Five trials (with seven comparisons) presented sufficient data for calculations on effect sizes for severity of cold episodes (Analysis 1.4). Again, none of the single trials found a significant effect over placebo. However, as study findings were similar across trials (I² statistic = 0% and Tau² = 0.00 and P = 0.86 in Chi² test) we report the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) for this outcome which is ‐0.24 (95% CI ‐0.07 to ‐0.40; P = 0.005), indicating a small effect over placebo.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 2 Number of participants with more than 1 cold.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 3 Duration: mean difference.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 4 Total severity score.

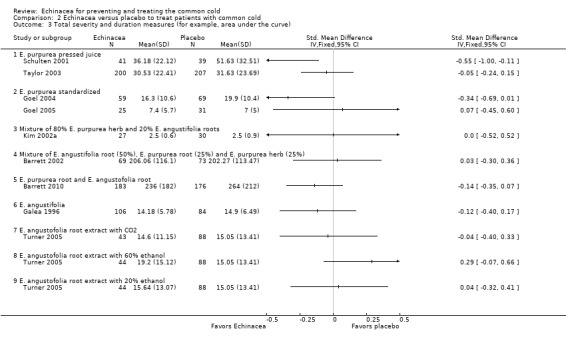

Secondary efficacy outcome measures for treatment or self treatment trials: total severity and duration measures; severity of symptoms at days two to four and at days 5 to 10; in trials with very early onset of treatment also the number of participants who developed the 'full picture of a cold'

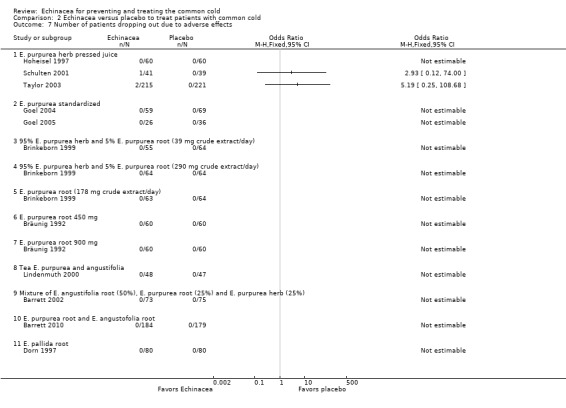

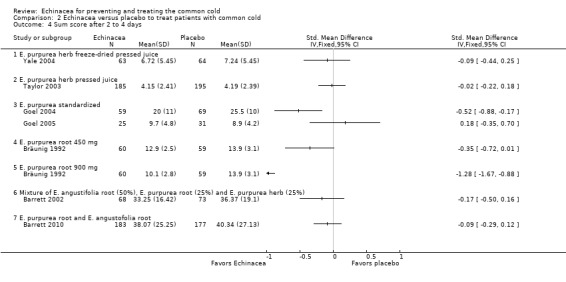

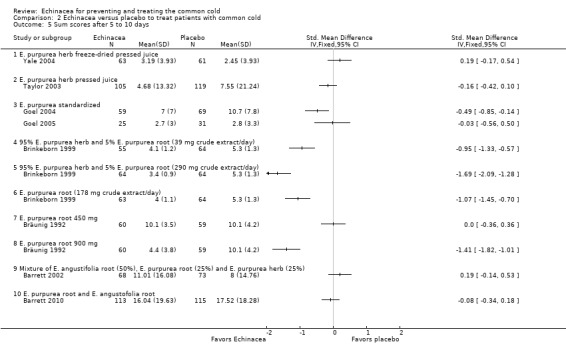

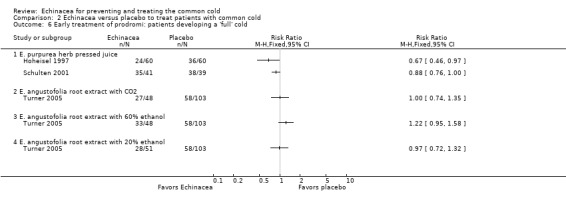

In nine trials (nine comparisons) measures integrating both severity and duration were presented in sufficient detail, or were provided by the authors, to calculate effect sizes (Analysis 2.2). The two trials on E. purpurea herb pressed juice preparations also reporting duration again reported conflicting results (Schulten 2001; Taylor 2003). The pooled SMD was not significant (SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.75 to 0.23; P = 0.30; I² statistic = 76%). This applies also to two trials testing a standardized extract of E. purpurea (SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.57 to 0.21; P = 0.20; I² = 40%). Trials of other extracts did not find any significant differences. While heterogeneity seems limited (I² statistic = 17%; Tau² 0.00; P = 0.29 in Chi² test) our SMD from meta‐analysis of all available studies has to be interpreted with great caution (SMD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.02; P = 0.10). Data on severity scores after two to four days (Analysis 2.4) and five to 10 days of treatment (Analysis 2.5) were reported in seven trials (eight comparisons) and eight trials (11 comparisons), respectively. Significant differences were found in two comparisons after two to four days and four comparisons after five to 10 days. As study findings were heterogeneous (I² statistic = 76% and 90%, respectively) we do not report a pooled effect estimate of all pooled data. For the standardized E. purpurea extract tested in two trials pooled SMDs were non‐significant (after two to four days: SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.88 to 0.48; P = 0.56 and after five to 10 days SMD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.75 to ‐1.00; P = 0.18). Only three trials reported the number of patients developing a "full" cold after the early treatment of prodromes (self treatment) (Analysis 2.6). For the two studies using the same Echinacea product (E. purpurea herb pressed juice) the pooled RR was non‐significant (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.14; P = 0.21).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 4 Sum score after 2 to 4 days.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 5 Sum scores after 5 to 10 days.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 6 Early treatment of prodromi: patients developing a 'full' cold.

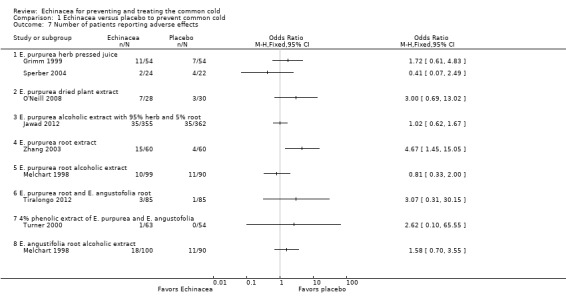

Secondary safety and acceptability outcomes for prevention trials: total number of drop‐outs and the number of participants reporting side effects or adverse events

For 12 comparisons in nine trials the number of patients dropping out (Analysis 1.6) has been reported. Two studies reported that significantly more patients were dropping out in the Echinacea group than in the placebo group (Jawad 2012 and the comparison using E. angustofolia root extracted with CO2 in Turner 2005). The other trials found no significant differences in the number of drop‐outs. As study results seem broadly consistent (I² statistic = 8%, Tau² = 0.02; P = 0.37 in Chi² test) we also report pooled results. The percentage of participants in the Echinacea groups terminating studies early was 12.7% compared to 9.0% in the placebo groups (OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.91; P = 0.06). For nine comparisons in eight trials the number of persons reporting adverse effects (Analysis 1.7) has been reported. Results were non‐significant in all trials except for one trial which found significantly fewer persons reporting adverse effects in the placebo group (Zhang 2003). In most of the trials there was a trend towards fewer adverse effects in the placebo groups. As some heterogeneity cannot be ruled out (I² statistic = 25%, Tau² = 0.10; P = 0.23 in Chi² test) our pooled findings are hard to interpret. 11.8% versus 8.6% of patients reported side or adverse effects (RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.35; P = 0.09).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 6 Number of patients dropping out.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold, Outcome 7 Number of patients reporting adverse effects.

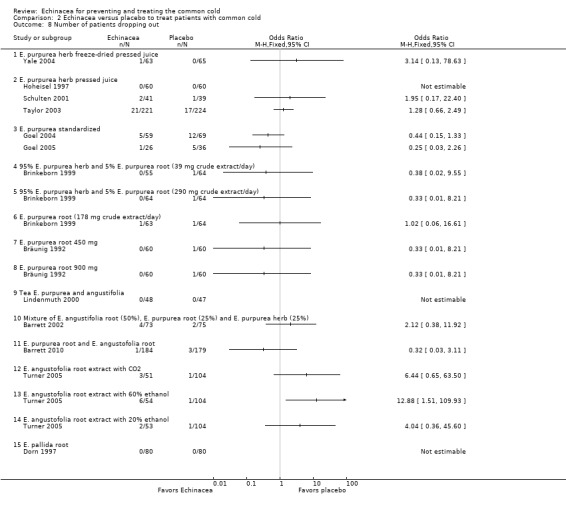

Secondary safety and acceptability outcomes for treatment or self treatment trials: total number of drop‐outs and the number of participants reporting side effects or adverse events

Numbers of participants dropping out were similar in Echinacea and placebo groups in the trials presenting these data (Analysis 2.8 to Analysis 2.9), except for E. angustofolia root extracted with 60% ethanol which led to more drop‐outs in the Echinacea group (Turner 2005). The number of patients reporting adverse effects did not differ significantly between treatment and control groups in the single trials. Heterogeneity was low (I² statistic = 0%, Tau² = 0.00, P = 0.84 Chi² test). Meta‐analysis showed a significant difference in the number of patients reporting side effects in the placebo groups (32.6%) and in the treatment groups (34.1%) (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.60, P = 0.03). One trial in children using a preparation made from pressed juice of E. purpurea herb found an increased frequency of rash in the experimental group (Taylor 2003).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 8 Number of patients dropping out.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Echinacea versus placebo to treat patients with common cold, Outcome 9 Number of patients reporting adverse effects.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our review shows that a variety of products prepared from different Echinacea species, different plant parts and in different forms have been compared to placebo in randomized trials. These preparations contain quite different amounts of bioactive components and hence are not biochemically comparable. Furthermore, trial approaches and methods for cold assessment were highly variable. Taken together, results from prevention trials suggest that a number of Echinacea products slightly reduce the risk of getting a cold in healthy individuals. If this conclusion is true, the lack of significance in individual trials could be due to a lack of statistical power (too few patients included in single studies). Although it seems possible that some Echinacea products also have effects over placebo for treating colds, the overall evidence for clinically relevant treatment effects over placebo is weak.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

For our review we could identify and include three unpublished trials which did not find significant effects over placebo (Galea 1996; Kim 2002a; Zhang 2003). We are also aware of at least one further unpublished, negative trial from the USA. During the search for an earlier review on Echinacea (Melchart 1994) one of the authors was informed by an expert in the field through personal communication that there were several negative trials from Germany (however, possibly partly of combinations). It seems possible that there are additional unpublished trials, though we think that it is unlikely that the conclusions of our review would change substantially; the evidence regarding treatment effects is weak and cannot justify recommendations to take Echinacea or a specific product. All single prevention trials included in our review yielded non‐significant results. Particularly in smaller trials, P values were far from statistically significant.

Quality of the evidence

The great heterogeneity of preparations tested makes conclusions difficult. Several of the newer trials tested products which were standardized on the content of a bioactive ingredient. However, the available research indicates that the clinical effects of (some) Echinacea preparations are likely to be due to several components which may have synergistic effects. Two of the tested products were standardized for known bioactive components, namely alkamides, cichoric acid and polysaccharides (Goel 2004; Goel 2005; Tiralongo 2012). Components (or one component) of the study medication have been analyzed and documented for several trials (Barrett 2002; Barrett 2010; Galea 1996; Jawad 2012; Melchart 1998; Turner 2000; Turner 2005; Yale 2004; Zhang 2003). Testing preparations that have been standardized to specific components seems like a desirable way to move forward. The quality of the included trials was heterogeneous as we considered 38% of the trials to have a high risk of bias while we considered 42% of the trials to have a low risk of bias.

In 2005, a further systematic review on the effectiveness of Echinacea for the treatment (not prevention) of colds was published (Caruso 2005). The authors concluded that the possible therapeutic effectiveness of Echinacea had not been established. A major criticism was that most studies (apart from two negative trials) lacked a proof of blinding. While we agree that successful blinding is crucial for the validity of a trial, we find it problematic to overemphasize this criterion when assessing the available evidence. First, the vast majority (93%) of placebo‐controlled RCTs provide no evidence of blinding success and, of those that do, the majority report less than satisfactory results (Fergusson 2004). Second, participant guesses at the end of a trial are also influenced by the perceived outcome and are not necessarily evidence of bias. Nevertheless, we agree with the authors of this review that the available evidence is far from convincing and that a lack of blinding can be a relevant problem in trials of Echinacea products.

Potential biases in the review process

Study selection and data extraction were performed by at least two review authors independently. Studies in which one of the authors were involved were handled by another review author. We checked study findings entered for effect size calculation against the original publications. However, it was a major challenge for the authors of this review to summarize the results of the included studies in a manner that is both concise and reflects the heterogeneity adequately. In our main analysis we did not pool studies unless they clearly investigated comparable Echinacea products. Yet, deviating from our protocol, we included some pooled estimates from meta‐analysis across different Echinacea preparations in the text. We believe that this decision is justified as a) it allows us to check whether study findings are consistent across studies and products and b) it provides a crude idea of the possible size of potential effects. However, we urge that these results have to be interpreted with caution and should not be interpreted as 'average' effects of Echinacea products.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A meta‐analysis (Schoop 2006b) of the three trials on induced rhinovirus infections included in our review (Sperber 2004; Turner 2000; Turner 2005) found that the likelihood of participants experiencing a clinical cold was significantly lower in the Echinacea groups. The results were pooled, although different Echinacea preparations were examined in the trials. These findings could indicate that the trials were too small to detect a small effect of the tested preparations. This conclusion is consistent with our results.

In 2007 another meta‐analysis of RCTs investigating the effectiveness of Echinacea products for preventing and treating common colds was published (Shah 2007). This review drew more favorable conclusions, especially on the effect of Echinacea on the cold duration, than we do. Shah 2007 used different inclusion criteria and also included trials investigating combinations of Echinacea. These authors heavily relied on meta‐analysis, pooling findings from studies investigating very different Echinacea preparations and from treatment and prevention trials in one analysis. If all these trials are interpreted as investigating the same treatment for the same purpose, then the evidence can be considered as more positive and the conclusions reasonable. For our main analysis we refrained from pooling studies testing different Echinacea preparations.

Other complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions for prevention and treatment have been investigated in systematic reviews. The evidence that vitamin C supplementation or probiotics used for prevention of the common cold, and zinc used for treatment of the common cold, are effective (Hao 2011; Hemilä 2013; Singh 2013a) is stronger than the evidence for Echinacea. Evidence for the effects of other CAM interventions is similarly limited (Pelargonium sidoides, Timmer 2009) or even weaker (saline nasal irrigation, Kassel 2010; increased fluid intake Guppy 2011; heated humidified air, Singh 2013b; garlic, Lissiman 2012; and Chinese medical herbs, Zhang 2010).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The most important recommendation for consumers and clinicians is to be aware that the available Echinacea products differ greatly. The overwhelming majority of these products have not been tested in clinical trials. It has been shown that labeling of products marketed in health food stores can be incorrect (Gilroy 2003). Our exploratory meta‐analyses suggest that at least some Echinacea preparations may reduce the relative risk of catching a cold by 10% to 20%. A risk reduction of 15% would mean that if 500 out of 1000 persons receiving a placebo would catch a cold this figure would be 425 of 1000 persons with an Echinacea product. This is clearly a small effect of unclear clinical relevance. Furthermore, we cannot say which Echinacea products have an effect of this size, or a greater or lesser effect. While there are some hints that both alcoholic extracts and pressed juices that are based primarily on the aerial parts of E. purpurea have beneficial effects on cold symptoms in adults, the evidence for clinically relevant treatment effects is weak. There are still many remaining doubts due to the fact that not all trials using such preparations show even a trend towards an effect.

As randomized controlled trials include limited numbers of participants and often exclude persons with relevant co‐morbidity, a review of such trials can only contribute limited knowledge on safety issues. The number of patients dropping out or reporting adverse effects did not differ significantly between treatment and control groups in prevention and treatment trials. However, in prevention trials there was a trend towards a larger number of patients dropping out due to side effects or reporting side effects in the treatment groups.The most relevant potential adverse effects of Echinacea preparations are probably allergic reactions (Huntley 2005; Mullins 2002). One trial suggested an absolute 5% increase in rash in children (Taylor 2003). Parenteral application of Echinacea preparation should be discouraged, as there is no evidence of either safety or effectiveness.

Implications for research.

In principle, further research is clearly desirable given the widespread use of Echinacea products. However, given the multiplicity and diversity of products on the market applying the knowledge gained from such studies will remain a challenge to persons without in‐depth knowledge of herbal preparations. The use of chemically well‐defined preparations is recommended to improve comparability of results from different studies. It would be desirable if experts in research on common colds could develop recommendations for a core set of outcome measures to be used and reported in randomized clinical trials. Trials investigating the prevention of colds need large sample sizes as the potential effects of Echinacea products are likely to be small.

Feedback

Duration of Echinacea dosage

Summary

I wish to comment on the Cochrane review 'Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold'. It is claimed in the Hot Topic of the Month (Relief from coughs and colds), August 2001, p. 5, para. 6.1, that "the German drug regulatory authority recommends that it be used for no longer than eight weeks at a time". I have asked the Consumer Network about the evidence for this and been told that it is not available. Nevertheless, I think that if it is indeed a recommendation of the German drug regulatory authority, it should be mentioned in both the review and the abstract.

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of my criticisms.

Reply

We appreciate this comment. It is correct that the German drug regulatory authority recommends that Echinacea preparations should not be taken for longer than eight weeks at a time. While there is no evidence that longer intake can be harmful, such a precaution seems justified in the absence of data on long‐term use. We included a statement on this issue in the review conclusion section 'Implications for practice'.

Klaus Linde

Contributors

David Potter Comment posted 02/06/2005

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 July 2014 | Amended | A mistake in the Abstract regarding treatment trials reporting data on the duration of colds has been corrected. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1997 Review first published: Issue 1, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 June 2013 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Change to authorship byline: new first author Marlies Karsch‐Völk. Dieter Melchart was not involved in this update. Inclusion criteria changed: now only randomized controlled trials and also studies on induced rhinovirus infections included. Outcome measures changed: duration of cold is now a primary outcome of treatment trials. Conclusions changed: possibly slight effect of Echinacea in the prevention of colds. Evidence for treatment effectiveness is weak. |

| 5 June 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. Seven new studies were included (Barrett 2010; Hall 2007; Jawad 2012; O'Neill 2008; Tiralongo 2012; Turner 2005; Zhang 2003). Two formerly excluded studies are now included (Sperber 2004; Turner 2000). One formerly included study is now excluded (Spasov 2004) and 12 new trials were excluded (Di Pierro 2012; Hauke 2002; Heinen‐Kammerer 2005; Isbaniah 2011; Minetti 2011; Narimanian 2005; Naser 2005; Saunders 2007; Schapowal 2009; Schoop 2006a; Wahl 2008; Yakoot 2011). |

| 15 March 2010 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted |

| 6 August 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 8 May 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 16 January 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 5 October 2007 | New search has been performed | Conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 12 September 2005 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 1 June 2005 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback and reply added. |

| 16 November 1998 | New search has been performed | Review first published. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Thorning (Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane ARI Group) for her help with the literature search and Liz Dooley (Managing Editor of the Cochrane ARI Group) for her patience when waiting for this update to be completed. Furthermore we would like to thank Dieter Melchart for his contribution to the previous versions of the review. The authors would also like to thank the following people for commenting on drafts of this review: Janet Wale, Ann Fonfa, Ajima Olaghere, Steven Yale, Zaina AlBalawi, Sree Nair, Mark Jones and Meenu Singh. We are indebted to the authors of primary studies who provided additional information, often to a considerable extent.

Bruce Barrett is supported by a K24 Mid‐Career Investigator Award from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. David Kiefer is a post‐doctoral research fellow, supported by a T32 National Research Service Award from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Embase.com search strategy

#10 #1 AND #9 #9 #4 NOT #8 #8 #5 NOT #7 #7 #5 AND #6 #6 'human'/de #5 'animal'/de OR 'nonhuman'/de OR 'animal experiment'/de #4 #2 OR #3 #3 random*:ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR crossover*:ab,ti OR 'cross‐over':ab,ti OR (doubl* NEXT/1 blind*):ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR trial:ti #2 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp #1 1922 #1.6 #1.1 OR #1.2 OR #1.3 OR #1.4 OR #1.5 #1.5 coneflower*:ab,ti #1.4 'e. purpurea':ab,ti OR 'e. pallida':ab,ti OR 'e.angustifolia':ab,ti #1.3 'echinacea purpurea'/de OR 'echinacea extract'/de OR 'echinacea purpurea extract'/de OR 'echinacea pallida extract'/de OR 'echinacea angustiflora extract'/de #1.2 echinac*:ab,ti #1.1 'echinacea'/exp

Appendix 2. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

S15 S5 and S14 S14 S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 S13 TI placebo* OR AB placebo* S S12 TI clinic* W1 trial* OR AB clinic* W1 trial* S11 (MH "Quantitative Studies") S10 (MH "Placebos") S9 TI random* OR AB random* S8 TI ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) W1 (blind* or mask*)) OR AB ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) W1 (blind* or mask*)) S7 PT clinical trial S6 (MH "Clinical Trials+") S5 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 S4 TI coneflower* OR AB coneflower* S3 TI ("E. purpurea" or "E. pallida" or "E. angustifolia") OR AB ("E. purpurea" or "E. pallida" or "E. angustifolia") S2 TI echinac* OR AB echinac* S1 (MH "Echinacea")

Appendix 3. AMED (Ovid) search strategy

1 exp echinacea/ 2 echinac*.tw. 3 1 or 2 4 randomized controlled trials/ 5 exp clinical trials/ 6 random allocation/ 7 double blind method/ 8 (clin* adj25 trial*).tw. 9 ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj25 (blind* or mask*)).tw. 10 placebos/ 11 placebo*.tw. 12 random*.tw. 13 or/4‐12 14 3 and 13

Appendix 4. LILACS (BIREME) search strategy

> Search > MH:"Echinacea angustifolia" OR MH:"Echinacea purpurea" OR MH:echinacea OR MH:HP4.018.251.105 OR MH:HP4.018.251.116 OR MH:B01.650.940.800.575.100.100.310 OR echinac$ OR "E. angustifolia" OR "E. pallida" OR "E. purpurea"

Appendix 5. Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) search strategy

| # 3 | 209 | #2 AND #1 Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=All Years Lemmatization=On |

|

| # 2 | 1,292,302 | Topic=(random* or placebo* or ((singl* or doubl*) NEAR/1 blind*) or allocat* or crossover* or "cross over") OR Title=(trial) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=All Years Lemmatization=On |

|

| # 1 | 1,605 | Topic=(echinac* OR "E. purpurea" OR "E. angustifolia" OR "E. pallida" OR coneflower*) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=All Years Lemmatization=On |

Appendix 6. Previous searches

For the first publication of this review in The Cochrane Library, 1999, Issue 1 (Melchart 1999) the following sources were searched:

MEDLINE (1966 to 1998): all hits for Echinac* screened;

EMBASE (1991 to 1998): all hits for Echinac* screened;

the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group Specialized Register: all hits for Echinac* screened;

the database of the Cochrane Field Complementary Medicine: all hits for Echinac* screened;

the database Phytodok (Munich, specialized on Phytomedicine) screening all clinical studies for Echinac*;

bibliographies of identified articles;

existing reviews;

manufacturers and researchers in the field (who were contacted to identify published and unpublished trials);

proceedings of phytomedicine congresses (International Congresses on Phytomedicine and Congresses of the German Society of Phytotherapy) (screened).

For the 2007 update we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 3); PubMed (1997 to September 2007); EMBASE (1998 to April 2007); AMED (to August 2005) and the Centre for Complementary Medicine Research (in Munich) (1988 to September 2007). We also contacted experts and screened references of reviews.

We searched PubMed and CENTRAL using the following terms combined with the highly sensitive search strategy devised by Dickersin (Dickersin 1994). 1 exp ECHINACEA/ 2 Echinacea 3 or/1‐2

We searched EMBASE and AMED using adapted terms. We searched the database of the Centre of Complementary Medicine Research in Munich for controlled trials of Echinacea.

We screened bibliographies of identified trials and review articles for further potentially relevant publications. We contacted experts in the field and asked about further published and unpublished studies.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Echinacea versus placebo to prevent common cold.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of participants with at least 1 cold episode | 9 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 E. purpurea herb | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 E. purpurea herb pressed juice | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 E. purpurea dried plant extract | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 E. purpurea root extract | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 E. purpurea root alcoholic extract | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.6 E. purpurea root and E. angustofolia root | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.7 4% phenolic extract of E. purpurea and E. angustofolia | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.8 E. angustifolia root alcoholic extract | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.9 E. angustofolia root extract with CO2 | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.10 E. angustofolia root extract with 60% ethanol | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.11 E. angustofolia root extract with 20% ethanol | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Number of participants with more than 1 cold | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 E. purpurea herb pressed juice | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 E. purpurea alcoholic extract with 95% herb and 5% root | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 E. purpurea root alcoholic extract | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |