Abstract

Background

A majority of Ethiopians rely on traditional medicine as their primary form of health care, yet they are in danger of losing both their knowledge and the plants they have used as medicines for millennia. This study, conducted in the rural town of Fiche in Ethiopia, was undertaken with the support of Southern Cross University (SCU) Australia, Addis Ababa University (AAU) Ethiopia, and the Ethiopian Institute of Biodiversity (EIB), Ethiopia. The aim of this study, which included an ethnobotanical survey, was to explore the maintenance of tradition in the passing on of knowledge, the current level of knowledge about medicinal herbs and whether there is awareness and concern about the potential loss of both herbal knowledge and access to traditional medicinal plants.

Methods

This study was conducted using an oral history framework with focus groups, unstructured and semi-structured interviews, field-walk/discussion sessions, and a market survey. Fifteen people were selected via purposeful and snowball sampling. Analysis was undertaken using a grounded theory methodology.

Results

Fourteen lay community members and one professional herbalist provided information about 73 medicinal plants used locally. An ethnobotanical survey was performed and voucher specimens of 53 of the plants, representing 33 families, were collected and deposited at the EIB Herbarium. The community members are knowledgeable about recognition of medicinal plants and their usage to treat common ailments, and they continue to use herbs to treat sickness as they have in the past. A willingness to share knowledge was demonstrated by both the professional herbalist and lay informants. Participants are aware of the threat to the continued existence of the plants and the knowledge about their use, and showed willingness to take steps to address the situation.

Conclusion

There is urgent need to document the valuable knowledge of medicinal herbs in Ethiopia. Ethnobotanical studies are imperative, and concomitant sustainable programmes that support the sustainability of herbal medicine traditions may be considered as a way to collect and disseminate information thereby supporting communities in their efforts to maintain their heritage. This study contributes to the documentation of the status of current traditional herbal knowledge in Ethiopia.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Herbal medicine, Traditional medicine, Ethnobotany

Background

Ethiopia has been described as one of the most unusual and important sources of biodiversity in the world [1], yet is perilously close to losing much of this rich diversity due to deforestation, land degradation, lack of documentation of species in some areas as well as of traditional cultural knowledge, and potential acculturation [2-5]. Intertwined with the irretrievable loss of important species of animals and plants is the risk of loss of traditional herbal medicine knowledge.

An estimated 80 to 90 per cent of Ethiopians use herbal medicine as a primary form of health care [6-9]. Despite significant recent improvements in modern health care, many rural communities continue to have limited access to modern health care due to availability and affordability [10,11]. It is widely acknowledged that the wisdom of both professional and lay healers in applying traditional medicine to support health and manage illness may be lost to future generations unless urgent efforts are made to document and disseminate the knowledge [3,4,7,12,13] and to engage the younger generation who may no longer be interested in learning the traditional methods [4,7,14]. Therefore Ethiopians, particularly those in rural areas, face an uncertain future in regard to ready access to affordable modern medical services and access to their traditional remedies.

Tradition

Herbalism is one aspect of traditional medicine practice in Ethiopia as it is in many other countries [15]. Herbs have traditionally been used in the home to treat family sickness, and occasionally traditional healers may be consulted. Traditional healers may be from the religious traditions of Cushitic Medicine, regional Arabic-Islamic medical system, or the Semitic Coptic medical system practiced by Orthodox Christian traditional healers [3], who are also referred to in Amharic as debteras. There may be many variations in approach within each system [16]. Spiritual methods are often used in combination with herbal applications particularly by the debteras, and the knowledge is traditionally passed down through the male line. When it comes to household herbal knowledge in the lay sphere, it is also generally considered that knowledge, in accordance with tradition, is preferentially passed on to a favourite child, usually a son [3,12,17,18], although a 2003 study by Gedif and Hahn [17] into the use of herbs for self-care, which primarily interviewed mothers, acknowledged mothers as the “de facto healers of the family treating accidents and ailments with medicinal plants”.

Significance of the study

This study examined whether (i) knowledge was transferred to the current generation of lay community members in Fiche, (ii) lay people are knowledgeable about the medicinal use of herbs, (iii) lay people continue to practice herbal medicine in the treatment of sickness within the home. An aim of the study was also to determine whether or not there is enthusiasm for the preservation of knowledge and skills for future generations. The ethnobotanical survey that constituted part of this research helped to identify the plants used by local community members, for future planting in their household and community gardens. To our knowledge, no ethnobotanical exploration had previously been conducted in this area (personal communication, TA). The information gained from this study may inform further studies and projects aimed at documenting herbal knowledge in communities and supporting continued practice and sustainability of traditional herbal medicine in Ethiopia and elsewhere.

Materials and methods

This case study was conducted using an oral history method, a technique for historical documentation which mirrors the cultural practice of passing on knowledge as an oral tradition, and encourages the subjects to present their experience of a specific event or period in the past [19]. It is a process of narrative building and within that framework the story of domestic life emerges. This gives contextual background to the information. A thematic analysis was applied to all interviews.

Ethics

Official collaboration with, and permission from, the Ethiopian Institute of Biodiversity and Addis Ababa University to conduct research ensured that the collection of local medicinal knowledge was compliant with current Ethiopian regulations relating to Access and Benefit Sharing. Ethics approval (No. ECN-10-24) from the Human research Ethics Committee of Southern Cross University was granted, and verbal permission was sought from and granted by each informant, with full explanation given in the local language as to the purpose of the research. Permissions were recorded on film.

Participants

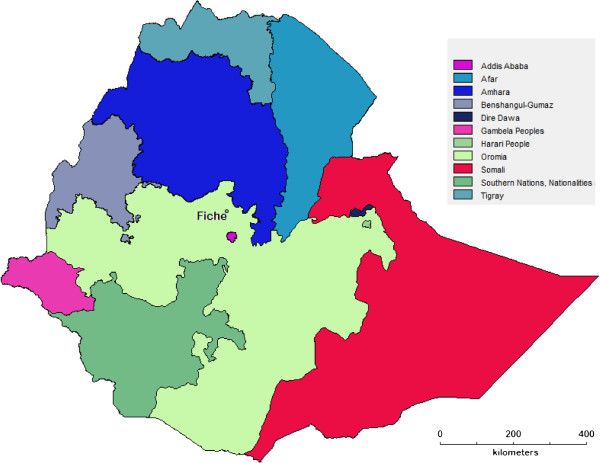

The focus of the case study was the town of Fiche, in the North Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Fiche is located 115 km north of Addis Ababa, 9°48′N and 38°44′E, at an elevation of 2700 metres above sea level, with a town population in 2007 of 27,493 [20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Ethiopia showing Fiche.

Fieldwork was conducted in January and February 2011. Six informants were initially recruited via purposeful sampling by a tertiary-educated, local representative who is knowledgeable about local herbs (referred to herein as ‘M8’) and who is planning a herbal garden at Fiche (called “Doyu-Armon”). M8 speaks English and provided some translation. The criterion for the sampling was being known in the community to have knowledge of medicinal plants and their use to treat ailments. Further informants were recruited thereafter by snowball sampling. The 15 informants consisted of 14 community members (8 males and 6 females) and a professional herbalist (male) of the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian tradition. In addition to the professional herbalist, three of the males and two of the females were considered by the community to be particularly skilled in herbal knowledge. Informants were aged between 39 and 70, with an average age of mid-forties. Informants are referred to as Male (M) or Female (F) and assigned a number.

Informants’ education levels varied from illiterate (80% of informants), to secondary school education completed (10% of informants), with one tertiary-educated informant (M8, who initiated the recruitment of informants and provided some translation) and they belonged to either the Amhara or Oromo ethnic groups. All spoke Amharic and one (M8) was also fluent in English. In addition to the informants, some incidental data was contributed by one of the authors (TA of the Ethiopian Institute of Biodiversity) in his capacity as translator and collector of voucher specimens.

The first informants recruited (2 women and 4 men including the professional herbalist) were identified by the local representative (M8) as persons with significant relevant knowledge, and subsequent informants were recruited by snowball sampling. This sampling method was effective and convenient as it utilised local knowledge to identify appropriate informants.

The first focus group (FG1, six people) provided an introduction of the lead researcher to the community and established the reasons for her presence. Following this session, more people came forward, interested in being part of the process. The professional herbalist was considered a respected Elder and his encouragement to the group was evident. The field-walk/discussion sessions were conducted in two household gardens and the escarpment (open pasture) above the River Jemma Gorge. The market survey was conducted at the Saturday market in Fiche, and the information was obtained from the vendors of the herbs who were mainly women.

Data collection

Field data were collected on six days during January and February 2011. A combination of focus groups (3), individual interviews (5), field-walk/discussion sessions (4) and one local market survey were conducted, with a tertiary-educated translator present at each session. Interview sites, all of which were in Fiche, were: Household garden (HG), homes of community members (H1 and H2), Doyu-Armon garden site (site for planned garden) (D-A), Escarpment above River Jemma Gorge (E) and Fiche Saturday market (M). The Jemma River is a tributary of the Blue Nile. Table 1 shows the timetable of fieldwork.

Table 1.

Timetable of fieldwork

| Present: | Session | Where | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1, M1, M8, R |

Field-walk 1 (W1) |

HG |

1 hour |

| F1, M1, M3, M4, PH, M8, R |

Focus group 1 (FG1) |

H2 |

2 hours |

| PH, M8, R |

Individual interview 1 (I1) |

H2 |

1 hour |

| F1, E, M8, R |

Field-walk 2 (W2) |

HG |

1 hour |

| Collection of voucher specimens | |||

| F1, E, M8, R |

Field-walk 3 (W3) |

HG |

1 hour |

| Collection of voucher specimens | |||

| F6, E, M8, R |

Individual interview 2/field-walk (I2) |

Next to D-A on pasture |

½ hour |

| + voucher specimen collection from Doyu-Armon garden site | |||

| Female stallholders, E, R |

Market survey (M) |

M |

1 hour |

| F4, F5, M8, R |

Individual interviews 3 + 4 (I3) |

H2 |

1 hour |

| M1, M2, M3, M5, M7, M8, F1, F4, F5, E, R |

Focus group 2 (FG2) |

H2 |

3 hours |

| M6, M8 |

Individual interview 5 (I5) |

H1 |

20 minutes |

| M1, M3, M5, M7, M8, E, R |

Field-walk 4 (W4) |

E |

2 hours |

| Collection of voucher specimens | |||

| F1, F2, F3, M1, M3, M5, M7, M8, E, R | Focus group 3 (FG3) | H | 2 hours |

Codes: F = Female, M = Male, PH = Professional Herbalist, E = Ethnobotanist (TA), R = Researcher (Ed’A), HG = Household garden, H1 and H2 = homes of householders, E = Escarpment above River Jemma.

Additional file 1 shows a plant collection site on the escarpment above River Jemma, as well as extracts of interviews.

The plant specimens collected by the Ethnobotanist (author TA) with the assistance of the informants were pressed, dried and identified following standard procedure and lodged at the EIB Herbarium in Addis Ababa. Translation was provided by TA and M8. All interview and focus group session translations were transcribed directly onto computer by the lead researcher, and all sessions were filmed, with the permission of participants. Later viewing of film footage provided useful review of data. In this way visual dynamics between informants could be viewed and further nuance from discussion picked up without the distraction of the recording process. Footage of 2 focus groups was viewed by a second translator to check areas where translation was indistinct, ambivalent, or not understood by the principal researcher. Other discussions, researcher observations and comments were recorded by hand into a notebook at the time, and a daily journal of all activities, with observations, comments and reflections, was written at the end of each day.

Interviews and focus groups were semi-structured. In an effort to ensure the women and men contributed equally during the mixed focus group discussions, an opening question (“How did you learn?”) was directed to each person individually. In this way, informants were able to provide in-depth answers in an individual manner as well as collectively. Occasional prompting, especially on the field-walk activities, would include the questions “What do you use this herb for?” How do you use this herb?” and “What do you call this herb?” allowing uninterrupted flow of discussion unless it strayed significantly from the topic, in which case an appropriate question was asked. Some contextual information was given by the free discussion in this way, often providing additional (unprompted) cultural background.

Data analysis

Grounded theory was applied as a method to conceptualise the data and identify themes. Grounded theory is a method which allows themes to emerge through analysis of data and may provide further deep, thick context to a theory by exposing underlying processes [21]. In keeping with this approach to interpretive analysis, transcripts from each interview were analysed repeatedly to identify emerging themes, and concept codes were assigned (open coding). Coding formed the basis for categories, and the data were examined within categories. Seven category headings were identified and under these all the data were accounted for. Data were examined for herb names, for disease names, and for formulas or prescriptions, and a quantitative list constructed The existing literature was examined for documented uses in Ethiopia of the herbs mentioned and included in this list as a commentary.

Results and discussion

Given that the research was conducted in a language and culture different from that of the principal researcher, some discussion of method with this aspect in mind is pertinent.

The intensive biography interview style of data collection associated with the oral history method allows a researcher to learn about informants’ lives from their own perspective [22]. The open discussion of memories, within the context of talking about herbs given to an informant as a child, gave the researcher the opportunity to observe and learn about informants within the context of their home life. Traditional medicine studies undertaken in Ethiopia are not often conducted in this way, with the perspective of an outsider exploring the current situation of the threat of loss of an important tradition, keeping cultural context at the forefront. Whilst being an outsider may on the one hand be seen as a limitation, on the other hand the researcher’s presence and interest in their plight highlighted outside interest and gave the community a sense that others considered their knowledge important and of value. The potentially negative issue of being an ‘outsider’ was ameliorated by the facts that the principal researcher is a herbalist in her own country, is able to speak a little of the language, was introduced to the community by a trusted member of that community and had previously visited Ethiopia (although not this area) on several occasions. The initiation of a programme to support establishment of a medicinal herb garden in the area (Botanica Ethiopia, see Additional file 2), also demonstrated tangible ongoing support to the community beyond the research programme.

According to Bryman [19], oral history testimonies have provided a method for the voices of the marginalised to be heard. It is not just people who may be marginalised, but also cultural traditions. In respect to the community group in Fiche, important cultural traditions and associated knowledge may be marginalised because community members may not have a strong voice in determining the future of those traditions. Further, the female members of this community may find their knowledge marginalised because despite the acknowledgement that women practice herbal medicine in the home [17,23], the prevalent belief [3,12,17,18] is that men (both professional traditional healers and in the family) are the prime holders of the knowledge. Time constraints of daily household chores may further restrict women’s participation in both receiving and passing on knowledge, and having that knowledge may not receive the importance it deserves [9].

The grounded theory approach to analysis was helpful, especially given the particular complexities associated with this study viz. the principal researcher was collecting data while immersed in a language, culture and environment different from her own. Repetition of certain words (translated) provided an opportunity to identify themes. For instance, the word “learnt” appeared at least once per person interviewed in describing different events, not surprising given the question asked but this provided a focus for analysis on first pass. In association with the words “learnt” or “remembered” would be a reference to a family member or influential person. The word “childhood” appeared frequently in this context. Another theme that emerged related to accessibility, availability and sustainability of herbs with subcodes referring to “disappeared”, “inaccessible”, “not available”, “hard to find”. Once emergent themes were identified, data were fragmented to lift coded elements out of the context of each interview [24] to list comments and information by group. Fragmented data were then reconnected and reviewed within the context of each interview. Throughout data collection, the researcher was critically aware that words emerged via translation and might have been influenced by translator bias. Mindful of this, the researcher would at times repeat the answer and ask for it to be translated back to the informants for verification. Table 2 lists the themes that emerged from coding.

Table 2.

Themes Subthemes that emerged via the coding process were clustered into major themes

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| How knowledge is acquired from previous generation |

People learnt from parents or other elders in the oral tradition |

| People learnt from the treatment of their own illnesses as children | |

| Awareness of loss of herbs |

Now some herbs are difficult to access |

| Some herbs are disappearing | |

| There is degradation of land | |

| Need to make effort to grow the herbs in household gardens | |

| Conservation of herbs |

Herbs need to be taken care of in the wild |

| Wildcrafting is endangering some species | |

| Passing on knowledge |

Children may not be interested in learning about the herbs |

| It is important to share the knowledge to save the herbs | |

| Safety and dosage |

Some herbs are toxic |

| Some herbs are dangerous if combined | |

| Some herbs are dangerous if the dosage is too high | |

| Dosages adjusted for children | |

| Gender |

Women in general know more about application than men |

| It is mostly women who sell the herbs in the marketplace | |

| Women have less time | |

| Herb usage | Herbs are used in the home to treat family members for a range of illnesses or conditions |

| Herbs are important | |

| Herbs are easily identified | |

| Herbs are sold in the market place |

Fourteen lay community members (6 females and 8 males) and one professional herbalist provided information about 73 medicinal plants from 42 families. Voucher specimens of 53 of these, representing 33 families, were collected and deposited at the Herbarium of the EIB in Addis Ababa. The families contributing the most taxa were Asteraceae (6), Solanaceae (6), Lamiaceae (5) and Fabaceae (5). The major classes of indications cited by informants were gastrointestinal complaints (25 plants) including megagna (12), tapeworm infection (8) and hepatitis (5); psychiatric conditions (7) and respiratory complaints (5).

All herbs named, their uses, and a comparison with uses elsewhere in the literature, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Herb data chart

| Botanical and family name [25] | Local name (Amharic) | Voucher no. | Use | Preparation | Informant (code) | Quotes and observations | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Achyranthes aspera L. Amaranthaceae |

Telenj/qay telenj |

1933 |

Part of a recipe for shotelay (Rhesus factor incompatibility in pregnancy) combined with Serabizu (Thalictrum rhynchocarpum), Quechine (Indigofera zavattarii), Y’imdur embway (Cucumis ficifolius), Tefrindo (Gomphocarpus purpurascens), Tult (Rumex nepalensis) |

The herbs are dried, chopped together and put in a cotton pouch to be hung around the pregnant woman’s neck in the seventh month. When the baby is born it is taken off the mother and put on the baby |

M3 |

“To be collected on a Wednesday or a Friday, having abstained from sexual relations, and having not spoken to anybody on the morning of the collecting day. The herbs are dried outside the house, chopped together and put in a cotton pouch. The cotton must be spun by a lady in menopause, and spun with her left hand not her right hand. The pouch is put on the lady’s neck and as soon as she gives birth it is taken from her and put on the baby’s neck….this is my specialty“ |

Anti-fertility [26] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fresh pulverised leaf or its juice is placed in the nostril or its juice is sniffed for epistaxis. The crushed fresh leaf is also placed in the genitalia as a remedy for menorrhagia and to stop post-partum haemorrhage [27] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes zoster, blood clotting[28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wound [29] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wound [30] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vaginal fumigation [31] |

| |

|

|

Wounds (kusil) |

Leaves rubbed and put on cut or wound |

F1 |

|

|

|

Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. |

Mrenz |

2016 |

Psychiatric disease (likuft) |

Used in a formula (see Solanum incanum) |

F3 |

|

Antiarrhythmic, vasoconstrictor, hypertensive agent, Na/K ATPase inhibitor [32] |

| Apocynaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Actiniopteris semiflabellata Pic.Serm |

Menna |

|

Burn (severe) |

Powdered roasted plant applied topically |

M2 |

“It was immediately cured by a shamagalay (old man) around the church. The doctor’s treatment had not worked. I asked the shamagalay why this worked better than the clinic treatment. He said it was to contain the wound so that it did not affect the bone” |

|

| Pteridaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Albizia anthelmintica Brongn. |

Musena |

|

Taeniasis |

Musena and Enkoko (Embelia schimperi) given but not in combination |

M7 |

Drink either with tella (local beer) |

Bark powder is cooked with meat and soup is taken as tenifuge [33] |

| Fabaceae |

|

|

|

The bark is mixed with Nug (Guizotia abyssinica) and sugar |

M5 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The bark is mixed with Nug (Guizotia abyssinica), chopped together |

F2 |

“If you take musena you may never see the segments…it kills all internally, it is digested. There will not be another infection” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

F1, F4 |

“We buy the Musena from the market” |

|

|

Allium cepa L. |

Shinkurt |

|

Taeniasis |

As part of a formula comprising Arake (spirit brewed with fermented grains) with Kosso (Hagenia abyssinica), Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis), Zingibil (Zingiber officinale) and Quorofa (Cinnamomum verum) |

F2 |

The herbs are used in the brewing of Arake |

Widely used as a medicinal plant worldwide |

| Amaryllidaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allium sativum L. |

Nech shinkurt |

|

Asthma |

3-4 cloves chopped and mixed with honey, dissolved by Kosso arake (spirit brewed with fermented grains and Hagenia abyssinica) |

F2 |

“The Kosso arake dissolves the Nech shinkurt. The Nech shinkurt can have a kind of side effect on the stomach (gastritis). If you want to protect yourself you may take lightly roasted Talba (Linum usitatissimum) or Abish (Trigonella foenum-graecum)” |

For common cold, malaria, cough, lung TB…asthma…parasitic infections, diarrhoea (etc.) [34] |

| Amaryllidaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Widely used as a medicinal plant worldwide |

|

Aloe debrana |

|

|

Wounds (kusil) |

|

M1 |

“A wound that is infected and very dry, contracted, they will use Aloe debrana and it will relax” |

|

| Christian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Xanthorrhoeaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aloe pulcherrima M.G.Gilbert & Sebsebe |

Sete eret |

2000 |

Asthma |

The sap is boiled with water. Sugar is added. This is filtered to about ½ teacup. Drink this and suck on a lemon. Do this for four days. |

M6 |

“You will burp the lemon taste, not the bitter aloe taste. After using this recipe I am free from asthma” |

“The species grows….in Gonder, Gojam, Welo and Shewa floristic regions. It is so far not known anywhere else. It occurs in a very sporadic manner, mainly on cliffs, and almost always in inaccessible places” [35] |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aloe spp. |

Eret |

|

Burn |

The burn is washed first with warm water and salt, then Eret placed on top |

F1 |

“We do not use alcohol to wash it like the doctors do” |

|

| Xanthorrhoeaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Andrachne aspera Spreng. |

Tekeze |

|

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

The root is chewed for stomach treatment and nausea (anti-emetic) |

M1, F1 |

“Not during pregnancy” |

Ascariasis, stomach distention, malaria, asthma, gastritis, liver disease and as anti-emetic [36] |

| Phyllanthaceae |

|

|

Snake bite |

The root is chewed, followed by lots of water. Will cause to vomit |

F1 |

|

|

|

Artemisia absinthium L. |

Ariti |

2024 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

Mixed with Tej sar (Cymbopogon citratus) and made into an infusion and filtered, and drunk |

F4 |

“Ariti tastes bitter, like Kosso” (Hagenia abyssinica) |

The juice of the powdered leaves is taken with honey to treat stomach ache [37] |

| Asteraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Mixed with Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis), and Zingibil (Zingiber officinale) made into an infusion, filtered and drunk |

M3 |

Remembers megagna as a childhood illness. “The pain immediately disappeared when this mixture was drunk” |

Cholagogic, digestive, appetite-stimulating, wound-healing, anticancer, antiparasitic [38] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Found on sale in Fiche market, as part of a fragrant bouquet (with Tej sar – Cymbopogon citratus, Ujuban – Ocimum basilicum var. thyrsiflorum, and Tenadam – Ruta chalepensis) |

|

|

Artemisia abyssinica Sch.Bip. ex A. Rich Asteraceae |

Chikugn |

1999 |

Evil Eye, combined with Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis) and Shinkurt (Allium cepa) |

Take the dried skin of a hyena and put the herbs in a pouch of the leather as a charm around the neck. |

M6 |

“I used to suffer from evil eye in childhood. If that is prepared and is smelling in the house, someone who is suffering from evil eye will start shouting and moving around; they will tie him down by force and apply in his nose. If you apply this, he will tell you the person with the evil eye up to the seventh generation” |

Anti-leishmanial, intestinal problems, bronchitis and other inflammatory disorders, cold and fever, anorexia, colic, infectious diseases (bacterial, protozoal), headache, amenorrhoea and dysmenorrhoea [39] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eye infection – topically [40] |

| |

|

|

Psychiatric disease (lekeft) |

|

F1 |

|

Haemostatic (nose), tonsillitis, cold, constipation, rheumatism [41] |

| |

|

|

|

Take Chikugn (Artemisia abyssinica) and three young leaves of Set eret (Aloe pulcherrima) with Nech shinkurt (Allium sativum), Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis), the whole plant of Tekeze (Andrachne aspera), along with the leaves of Chat (Catha edulis) and Ye ahiya joro (Verbascum sinaiticum): chop together. The juice is applied to the nose |

F2 |

“My father was told by somebody” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whole herb is use for tonsillitis [42] |

| |

|

|

Fumigant for milk machinery |

|

F1 |

|

|

|

Asparagus africanus Lam. |

Seriti |

1928 |

Rituals such as circumcision, and giving birth |

Branch hung in the doorway |

M1 |

Considered cleansing because “women are unclean just after giving birth” |

Fresh pulverised root taken mixed with water to stimulate milk secretion. The use of the plant against gouty arthritis and as abortifacient have been recorded [43] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M8 |

|

|

| Asparagaceae |

|

|

Hung on the door where Tella (local beer) is being made, as protectant against uncleanliness (someone who is menstruating, or has recently had sexual relations) |

|

F1 |

|

|

|

Brucea antidysenterica J.F. Mill |

Fit aballo, aballo |

2013 |

Eczema (chiffe) |

The leaves are collected and dried, the powder is then applied to the skin |

F2 |

“I had this disease in childhood” |

Bullad (weight loss, fever, itching, diarrhoea) [28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evil eye (tied around neck) [30] |

| Simaroubaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cancer treatment, diarrhoea, evil eye, leishmaniasis, rabies, scabies, skin disease, wound [12] |

|

Calpurnia aurea(Aiton) Benth. |

Digita |

2008 |

Child with diarrhoea (tekmet) |

The leaves of the young shoots from seven plants of Digita are rubbed in the hands for the juice; the juice is mixed with water Dosage is very important, depending on the age of the child |

F3 |

“5 year old, 1 teaspoon, just once. This is what I had as a child”. Some discussion about the toxicity of this plant |

Decoction of the fresh leaf has been used against hypertension. Quinolizidine alkaloid, calpurnine, has been isolated [44] |

| Fabaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M1 |

“The stem bark is poisonous. The dosage should be measured carefully. Only the young shoots are used. Even then one has to be very careful.” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diarrhoea [45] |

| |

|

|

|

|

F1 |

“You can become crazy from it. If you go crazy, then you are going to die” |

Amoebiasis, giardiasis [30] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kuruba (diarrhoea) [28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Used as a fish poison or as a cure for dysentery [46] |

|

Capparis tomentosa |

Gumero |

|

Psychiatric disease |

In formula (see Solanum incanum) |

F3 |

|

Bleeding after delivery [30] |

| Lam. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Capparaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Catha edulis (Vahl) Endl. |

Chat |

|

Psychiatric disease |

In formula (see Artemisia abyssinica) |

F2 |

Frequently observed sold in streets |

Ephedrine has been isolated from this plant. Possesses psychostimulant properties [47] |

| Celastraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chenopodium murale L. |

Sinko |

1930 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

The young shoots are collected with scissors and rubbed through a sieve as used for the domesticated grass Tef (Eragrostis tef) |

F4 |

|

|

| Amaranthaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cinnamomum verum J. Presl |

Qorofa |

|

Taeniasis |

In formula (see Allium cepa) |

F1 |

|

|

| Lauraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Croton macrostachyus Hochst. Ex.Delile Euphorbiaceae |

Bisana |

2007 |

Skin rash |

Mixed with egg yolk and applied to the skin |

F1 |

|

Aphasia, ascariasis, constipation, eye disease, haemorrhoid, induction of abortion, purgative, ringworm, taeniasis, stomach ache, venereal disease control [12] |

| |

|

|

Skin rash |

The fresh bud is cut and the fluid applied to the rash. If the problem is on the head, the head is shaved and bud fluid applied |

M8 |

|

|

| |

|

|

Dandruff |

|

|

|

Scabies, kuruba (diarrhoea), hepatitis, Tinea versicolour [28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria [30] |

|

Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf |

Tej sar |

2004 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

Mixed with Ariti (Artemisia absinthium) |

F5 |

Found at the marketplace as part of a fragrant bouquet |

Treatment of heart, chest and stomach complaints [48] |

| Poaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stomach ache, smallpox, common cold [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ascariasis [30] |

|

Datura stramonium L. |

Astenagir/Astenagirt |

1940 |

Hallucinogenic |

|

M8, E |

|

Eye disease (‘crying eyes’) (topical), bad breath (smoke inhaled, fungus infection of the head (topical), mumps (topical), relief of toothache (vapour inhaled), rheumatic pain (vapour inhaled), treatment of burn (topical), wound (topical) [12] |

| Solanaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Swelling (topical), toothache (inhalation), dandruff (topical) [49] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Swelling, toothache, dandruff, wounds [28] |

|

Echinops kebericho Mesfin |

Kerbericho |

2001 |

|

To dispel nightmares in children |

E |

Found on sale in Fiche marketplace |

Constipation, headache, heart pain, stomach ache, typhus [12] |

| Asteraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fumigant after childbirth. Typhus fever. Stomach ache. Snake repellent in the house. Intestinal pains [50] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lung TB, leprosy, syphilis [51] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cough [49] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evil eye [28] |

|

Embelia schimperi Vatke Myrsinaceae |

Enkoko |

2032 |

Taeniasis |

Chopped with Musena (Albizia anthelmintica) and Nug (Guizotia abyssinica) and eaten |

M3 |

|

Powder of fruit mixed with water and taken as taenicide [52] |

| |

|

|

|

With Musena (Albizia anthelmintica) and Nug (Guizotia abyssinica), taken with a drink of Tella (local beer) |

M1 |

“Must be taken simultaneously with Tella. Drink, then jump up and down to dissolve internally. (M7) |

Taeniasis, disinfectant [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taeniasis, ascariasis [48] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tapeworm [30] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M5 |

If not taken with Tella, you will become dizzy and fall” (M5) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M7 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M2 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M1 |

“Enkoko and Musena are both deadly” |

|

| |

|

|

|

With Meterre (Glinus lotoides) and Kosso (Hagenia abyssinica) |

M8 |

“I remember my mother giving me this combination” |

|

| |

|

|

|

The ripe fruits are collected and the exocarp removed. Fruit swallowed directly using water |

F2 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M3 |

“It is ok to take Enkoko, Musena and Nug together” |

|

|

Eucalyptus globulus Labill. |

Nech bahirzaf |

2027 |

Fever with headache (mich), colds |

Apply rubbed leaves directly to nose |

F5 |

|

Leaves are boiled with water and the vapour inhaled to treat cough, flu and sore throat [53] |

| Myrtaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Euclea racemosa L. |

Dedaho |

2028 |

Warts of the rectum |

The root is to be collected early in the morning before urination. The root is dug up then boiled, and a full small teacup of the filtrate must be drunk before food. After the medicine is drunk well prepared food is eaten and well prepared Tella (local beer) is drunk |

M6 |

“Finally a kind of faeces will come out. If this does not happen initially, then the process is repeated the next day” |

Gonorrhoea, uterine prolapse, haemostatic, gastritis, diarrhoea, cataract, acne, chloasma, eczema, constipation, rabies, vitiligo, epilepsy [54] |

| Ebenaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Euphorbia tirucalli L. |

Qencheb |

2026 |

Scorpion bite |

The skin around the bite is slashed, and the milky sap applied |

M5 |

“The scorpion has a venom that gives gland pain for three days. After this application I was ok. Previously with a bite I suffered for three days. This time I was back at work in three hours. I had a small glandular response this time” |

Reported use in India for scorpion bite [55] |

| Euphorbiaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Galium simense Fresen. |

Chogogit |

1998 |

Skin fungus (qworqwor) |

The leaf is rubbed to get the juice which is applied to the affected place; the plant is then discarded. When applied, it irritates and causes a little bleeding. The next day it is washed off, and the patient has to wear newly washed clothing |

E |

“It will never come again” |

Extract of fresh leaves and inflorescences is used in Ethiopia to dress new wounds and cuts [56] |

| Rubiaceae |

|

|

|

|

M1 |

|

Snake bite [13] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M6 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M8 |

|

|

|

Glinus lotoides L. |

Meterre |

2031 |

Taeniasis |

Mixed with Nug (Guizotia abyssinica) and Musena (Albizia anthelmintica). Taken orally as a paste |

F1, F5 |

|

Ascariasis, taeniasis, diabetes [12] |

| Molluginaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Cleaned and ground with Nug (Guizotia abyssinica), added sugar and eaten before food. Fast until noon before taking it, then the first meal afterwards should be soup. |

E |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

Tapeworm – fruit powder mixed with Nug is taken orally [28] |

| |

|

|

|

Meterre with Nug OR Musena with Nug |

M1, M7, M8 |

Remembers mother giving him all three |

|

| |

|

|

|

Meterre, Enkoko (Embelia schimperi) and Nug (Guizotia abyssinica) |

M8 |

|

|

|

Gomphocarpus purpurascens A. Rich. |

Tefrindo |

2005 |

Rhesus Factor problem in pregnancy (shotelay), as part of formula |

|

M3 |

|

|

| Asclepiadaceae |

|

|

(see Achyranthes aspera) |

|

|

|

|

|

Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass. |

Nug |

|

Taeniasis |

Used as a binder with many preparations, mentioned here for tapeworm infection |

F1 |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

|

| Asteraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M1 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M2 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M3 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M5 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M7 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M8 |

|

|

|

Hagenia abyssinica J.F. Gmel |

Kosso |

2025 |

Taeniasis |

The flower taken with Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis), Shunkurt (Allium cepa), Zingibil (Zingiber officinale) and Qorofa (Cinnamomum verum) |

F1 |

|

Female flowers are employed as a taenicide against Taenia saginata[57] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eye disease, hypertension, scabies, m[12] |

| Rosaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Provides a strong and widely used anthelmintic [46] |

|

Hordeum vulgare L. Poaceae |

Gebs |

|

Hypertension |

Taken as a fermented barley drink. Gebs (germinated barley), Mashilla (Sorghum spp.) are baked together like a bread. This is broken up and fermented together with beqil (malt starter), brewed and distilled. Drunk from a shot glass |

F1 |

|

Hordenine with diuretic and in large doses with hypertensive action has been isolated [58] |

|

Indigofera zavattarii Chiov. |

Quechine |

|

Rhesus factor problem in pregnancy (shotelay) |

In formula: see Achyranthes aspera |

M3 |

|

|

| Fabaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jasminum grandiflorum L. |

Tembelel |

1957 |

Abdominal pain |

The root is chewed |

M1 |

|

|

| Oleaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Laggera tomentosa (Sch.Bip.) |

Shiro kese |

1943 |

Unexplained stomach problems (megagna) |

Leaves crushed and inhaled |

PH |

|

|

| Asteraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Laggera crispata (Vahl) Hepper & J.R.I. Wood |

Ras kebdo |

1929 |

Dandruff (forefore) |

Leaf rubbed and applied to the scalp |

F5 |

|

|

| Asteraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leonotis ocymifolia (Burm.f.) Iwarsson Lamiaceae |

Feres zeng |

1942 |

Headache (ras metat) |

The collected leaves are rubbed between hands and put into nostrils to inhale |

F6 |

“Particularly for headaches with tonsillitis. It cures it well. If not, the patient should be taken to the doctor. Go to a traditional medicine healer for headaches with tonsillitis” |

|

| |

|

|

|

OR |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The juice is squeezed out and drunk with coffee. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Ulcer of the neck (nkersa) |

Chopped leaves are applied to the ulcer for 24 hours |

M7 |

“People here assume it is cancer of the neck, but it is an ulcer. My uncle tried many things but finally he cured me with this” |

|

| |

|

|

For sick chickens |

With Aya joro (Verbascum sinaiticum) |

F1 |

|

|

|

Lepidium sativum L. Brassicaceae |

Feto |

2020 |

Unexplained stomach problems (megagna) |

Ground, mixed with lemon juice and water |

F5 |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

Skin problems, fever, eye diseases, amoebic dysentery, abortion and asthma, intestinal complaints [59] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aphrodisiac, gastritis, headache, ringworm, buda beshita (evil eye) mich (fever with headache) [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stomach ache [30] |

|

Leucas abyssinica (Benth.) Briq. |

Aychedamo |

1941 |

Eye infection |

|

E |

|

For eye diseases, twigs of Leucas abyssinica are crushed and coated on eyes [60] |

| Lamiaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Linum usitatissimum L. Linaceae |

Talba |

|

Demulcent |

Option as protective against gastritis when used with Allium sativum in treatment for asthma |

F2 |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

|

|

Lippia adoensis Hochst. Ex Walp. Var.Koseret Sebesebe |

Koseret |

1931 |

Bee attractant |

|

F1 |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

Dried leaves powdered together with barley eaten to get relief from stomach complaints [61] |

| Verbenaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria, fever, aphrodisiac [62] |

|

Malva verticillata L. Malvaceae |

Lut |

1935 |

Expulsion of placenta in cow |

The root is dug up and chopped and given as a decoction to cow |

F6 |

|

|

|

Maytenus arbutifolia (Hochst. Ex A. Rich.) R. Wilczek |

Atat |

2023 |

Psychiatric disease (in formula – see Solanum incanum) |

|

F3 |

|

A number of Maytenus spp. Are used in traditional medicine to treat various disorders including tumors. A tumor inhibitor, maytansine, has been extracted [46] |

| Celastraceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Myrsine africana L. Primulaceae |

Kechemo |

2022 |

Taeniasis |

Fruits are collected, chopped and filtered. Filtrate is drunk to expel tapeworm |

F2 |

“If Kechemo does not work, go for one of the other ones – Musena (Albizia anthelmintica), Enkoko (Embelia schimperi), Kosso (Hagenia abyssinica)” |

Fruit powder paste with Nug seed is taken against tapeworm and ascariasis [63] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Twigs used as a toothbrush [46] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. Solanaceae |

Tembaho |

2029 |

Repels snakes from garden |

|

F1, E |

|

|

|

Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. Ex Benth. Lamiaceae |

Demakese |

1926 |

Fever with headache (mich) |

Rub in the hand and squeeze to get juice, add to coffee or drink |

F5 |

Demonstrated putting a gabi – heavy cotton shawl – over the head for inhalation of vapour |

The fresh leaves are squeezed and the juice sniffed to treat coughs and colds. The juice is also used as eye rinse to treat eye infections. The crushed leaves are put in the nostrils to stop nose bleeding [64] |

| |

|

|

Influenza or cold |

OR |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Fever with headache |

Boil the leaves, place on a hot iron pan and inhale the vapour |

|

Found on sale in Fiche market |

Cough, cold, headache, eye infection, hematuria, mich (fever with headache) [12] |

| |

|

|

|

OR |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Apply rubbed leaves directly into the nose |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Juice in coffee |

F6 |

“If the juice of Demakese is red when the herb is rubbed by a person, then the person has mich. If it is green, it is not mich. The mother or the daughter will apply this” |

Kusil (wound), mich (fever) [28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mich [29] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mich [4] |

|

Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. Cactaceae |

Culcal |

|

Haemorrhage in childbirth |

In a formula (see Periploca linearifolia) |

M3 |

|

|

|

Otostegia fruticosa |

Tinjut |

1932 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

|

F1 |

Found on sale in Fiche market |

Insecticide, disinfectant, as a fumigant [12] |

| (Forssk.) Schweinf. ex Penzig |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lamiaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Periploca linearifolia Quart.-Dill. & A.Rich. Apocynaceae |

Tikur hareg |

|

Haemorrhage in childbirth |

Combined in a formula with Culcwal (Opuntia ficus-indica) and Qeret (unidentified). All are chopped together and then the juice is collected separately (filtered), used as ink to write on paper as a charm hung around the neck |

M3 |

“The debtera will write a charm with the filtrate and put it on her neck, and the blood will stop” |

|

| |

|

|

Prepared by debtera: |

A potion is prepared, buried in the ground for a week. When opened, the inky fluid is used as an ink to write a spell, or charm. Alternatively, the ink is used to tattoo into the skin with a needle |

M3 |

“The debtera will use this with other herbs to make a potion. This is put in a bottle and buried for seven days before September 11 (Addis amet – New Year’s Day). When opened it will have an inky constituency. The debtera will then use a pen made from Arundo (bamboo), and will write on white paper. It is then worn on the neck. Another way is to tattoo the ink into the skin with a needle” |

|

| |

|

|

To keep the wife from straying |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

To stop enemies from attacking |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

To prevent bullets from penetrating |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

To keep devils away |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

To stop pain |

|

|

|

|

|

Phytolacca dodecandra L’Herit |

Endod |

1927 |

Bilharzia |

|

E |

|

Molluscide against Bilharzia [46] |

| |

|

|

Contraception |

The whole roots of 7 young plants without branch, flower or fruit (sterile) are collected, being careful to get it all, on a Friday or a Monday. These are chopped and then mixed with honey, which is collected in October. The woman should take it at the end of menstruation |

F1 |

Debate on this application. Some say the woman should sleep with her husband on the day she takes the medication. “If she sleeps with her husband the ovary will not be badly affected” (M1). “If she goes to the doctor they will clean up that one and she will become pregnant” (F1). “She has to continue sexual relations to stop her ovary being badly affected” (M1). “She has to go to hospital” (M3). Some say it does not matter; used as a contraceptive, the woman will stay without child for 5–6 years. If she wants to become pregnant, she has to take an antidote (merfchow) – another plant. M7 says “If she takes the endod she is permanently sterile”. F1 says “If you spray poison on a flower, it will die”. M2 says “I gave it to my wife and 18 other people. No-one has given birth after that. My wife now wants to have a baby and cannot” |

Ascariasis, eczema, gonorrhoea, infertility, liver disease, malaria, rabies, soap substitute, syphilis [12] |

| Phytolaccaceae |

|

|

|

|

M1 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M2 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

M3 |

|

Rabies [4] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M7 |

|

|

| |

|

|

Skin blisters (ekek) – viral infection |

The chopped fruit is mixed with water as a wash for the hands |

M8 |

|

|

|

Podocorpus falcatus (Thunb.) R.Br.ex Mirb. Podocarpaceae |

Zegba |

|

Hepatitis formula |

Formula: |

M2 |

“My uncle took the leaf of Zegba and leaf of Togor and leaf of Nechilo. Then the root of Chifrig and the young shoot of Yerzingero addis and then Embwacho and the whole plant of Serabizu and the young shoot of Gesho. All this was put together, chopped, added to water and stirred. This is applied to whole body of the child every morning for seven day, starting on a Wednesday or a Friday and it must be a cloudy day. But it must not be too cloudy” |

Four species of Podocarpus including Podocarpus falcatus all exhibited strong inhibition against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, klebsiella pneumonia and Candida albicans[65] |

| |

|

|

|

Zegba |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Togor leaf (unidentified) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Nechilo (unidentified) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Chifrig (Sida massoika) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Yezingero addis (unidentified) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Embwacho (Rumex nervosus) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Serabizu (Thalictrum rhynchocarpum) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Gesho (Rhamnus prinoides) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Topical application |

|

|

|

|

Polygala hottentotta |

Etse adin |

1996 |

Anti-venom |

|

F5 |

|

|

| C. Presl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Polygalaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rhamnus prinoides L’Herit |

Gesho |

1952 |

Hepatitis (in formula) |

|

|

Found on sale in Fiche marketplace |

|

| Rhamnaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rhus retinorrhoea Steud. Ex A.Rich. Anacardiaceae |

Tilum |

2009 |

Wounds |

Rubbed in hands and then put on wound |

M4 |

|

|

|

Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. Polygonaceae |

Mekmeko |

2012 |

Hypertension |

|

F1 |

|

Gonorrhoea, lung TB, leprosy, fever [66] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Itching skin [4] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extracts drunk to control ‘mild form of diabetes’ [46] |

|

Rumex nepalensis Spreng. Polygonaceae |

Tult |

1936 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

The root is dug out and chewed. If Tult is not available, then the leaves of Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis) may be used instead |

M2 |

Childhood memory of use. “Tult is very bitter. I was forced to chew it, I would be beaten if I did not chew it” |

Amoebiasis, tonsillitis, uterine bleeding [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal cramp, child diarrhoea, toothache, liver disease, eye infection [4] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stomach ache [13] |

| |

|

|

Rhesus factor problem in pregnancy |

Part of formula (see Achyranthes aspera) |

M3 |

|

|

|

Rumex nervosus Vahl. |

Embwacho |

2011 |

Eye problems |

Leaves are collected, dried and pounded |

F5 |

Remembers this from childhood |

For dysentery, roots powder of Rumex nervosus mixed with melted butter. Stomach ache, roots in a honey paste dressing. Warts (kintarot), roots powder on cut edge [49] |

| Polygonaceae |

|

|

Wound (kusil) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Hepatitis |

In formula (see Podocarpus falcatus) |

M2 |

|

|

| |

|

|

Roundworm |

Stem chopped with salt |

M1 |

‘My father collected embwacho and he kept a stem and chopped it in small pieces, added salt, gave it to me and forbade me from eating for one hour. After three days there was expulsion of worms and no problem since then” |

|

|

Ruta chalepensis L. |

Tenadam |

1997 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

In formula (see Artemisia absinthium) |

M3 |

“The pain immediately disappeared” |

Snakebites, headaches, abdominal pain, strained eye, head lice, fever, poor blood circulation, local paralysis, nervous tension, cough, asthma, infected wound, rheumatism. An infusion is also used as a tea to treat headaches, cold, heart pain, earache and intestinal disorder. Dried fruits boiled with milk are used against diarrhoea, or with Tella (local beer) or “wet” (stew) against influenza [67] |

| Rutaceae |

|

|

|

Chew the leaves |

M2, M4 |

Use if Tult (Rumex nepalensis) not available |

|

| |

|

|

|

Combine with Dingetegna (Taverniera abyssinica) and wood ash mixed with a little water |

F1 |

Will cause to vomit |

|

| |

|

|

Colic in baby |

|

M3 |

Tenadam and Ariti (Artemisia absinthium) have the same use for treating the stomach” |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

PH |

Found on sale in Fiche marketplace |

Stomach problems [68] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evil eye and ‘flu’ [28] |

|

Sansevieria ehrenbergii Schweinf. Ex Baker |

Wonde cheret |

|

Ear infections |

|

F1 |

|

|

| Asparagaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sida massaica Vollesen |

Chifrig |

1956 |

Roundworm |

The whole part is ground and made into an infusion, filtered and drunk |

F5 |

|

|

| Malvacaeae |

|

|

Hepatitis |

In formula (see Podocarpus falcatus) |

M2 |

|

|

|

Solanum americanum Miller |

Y’ayit Awut |

1937 |

Gonorrhoea |

Leaves eaten as a vegetable. Root chopped, infused and drunk |

E |

|

|

| Solanaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solanum anguivi Lam. |

Zerch embway |

1938 |

Scabies |

|

E |

|

Lymphadenitis [4] |

| Solanaceae |

|

|

Nosebleed |

Root used to brush teeth, the nosebleed will stop |

F5 |

|

|

| |

|

|

Gonorrhoea |

Root infusion |

E |

|

|

|

Solanum incanum L. |

Embway |

2030 |

Psychiatric disease (lekeft) (in formula) |

Young shoots (without branch), combined with: |

F3 |

|

Stomach problem, snake bite, chest pain, tonsillitis, mich[68] |

| Solanaceae |

|

|

Nosebleed |

Mrenz root (Acokanthera schimperi) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Gumero root (Capparis tomentosa) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Atat (Maytenus arbutifolia) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

All plants are combined and all the juice is applied through the left nostril. The combination may also be inhaled from smoke |

M6 |

“A nun showed me” |

|

|

Stephania abyssinica (Quart.-Dill.& A.Rich.) Walp. |

Y’ayit joro/Shinet |

2002 |

Toothbrush |

Teeth brushed with the root |

M5 |

|

Rabies [29] |

| Menispermaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Used in traditional medicine to treat various stomach disorders and syphilis [46] |

|

Taverniera abyssinica A. –Rich. |

Dingetegna |

|

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

Taken with Tenadam (Ruta chalepensis) and Amed (wood ash), mixed together with a little water and drunk |

F1 |

“Will cause to vomit” |

“Sudden disease”, headache, stomach ache [12] |

| Fabaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vomiting, dysentery [28] |

|

Thalictrum rhynchocarpum Dill. Quart.-Dill & A.Rich. |

Serabizu |

2003 |

Rhesus factor problem in pregnancy (shotelay) as part of formula- see Achyranthes aspera |

|

M3 |

|

Menorrhagia [12] |

| Ranunculaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urinary tract infection [29] |

| |

|

|

As part of hepatitis formula (see Afrocarpus podocarpus) |

|

M2 |

|

|

|

Thymus schimperi Ronniger |

Tosigne |

1955 |

Whooping cough |

Boiled leaves, drunk as a tea |

F4 |

Found on sale in Fiche marketplace |

Used medicinally for headaches and coughs [69] |

| |

|

|

|

|

F5 |

|

|

| Lamiaceae |

|

|

Hypertension |

Boiled leaves, drunk as a tea |

F4 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

F5 |

|

|

|

Trigonella foenum-graecum L. |

Abish |

|

Demulcent |

Mixed with garlic in the treatment of asthma (see Allium sativum), to protect against gastritis which may be caused by strong application of Allium sativum |

F2 |

Found on sale in Fiche marketplace |

Used in treating skin and stomach disorders [46] |

| Fabaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Verbascum sinaiticum Benth. |

Ye ahiya joro |

2034 |

Sick chickens |

Together with Feres zeng (Leonotis ocymifolia) |

F1 |

|

|

| Scrophulariaceae |

|

|

Psychiatric disease (lekeft) |

In formula (see Artemisia abyssinica) |

F2 |

|

|

|

Verbena officinalis L. |

Aqwarach/ |

1950 |

Tonsillitis |

Chewed |

F5 |

“My mother would chew it, and she has to take 2 birr* for this. Unless they take the money they cannot be cured. If you refuse, it does not work” |

Leaf and/or root juice taken against diarrhoea. Decoction of leaf employed as gargle for tongue disease, sore throat and toothache [70] |

| |

Attuch/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Verbenaceae |

Telenz/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Hulegeb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

*Birr is the unit of currency in Ethiopia |

Dysentery, digestive after eating raw meat, eczema, eye disease, heart disease, heart pain, indigestion, induction of diarrhoea and emesis to relieve indigestion, insomnia, liver disease, malaria, mumps, snake/rabid dog bite, sore throat, stomach ache, stomach trouble, tongue disease, tonsillitis [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stomach disorder, Herpes zoster, ear problems, evil eye, snake bite, ascariasis [28] |

|

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal |

Gizawa |

2033 |

Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) |

Root is peeled then used as a fumigant by burning it and inhaling the smoke |

M4 |

“Gizawa is my favourite medication. Especially for the stomach. Use the root, peel it, then use it as a fumigant” |

Decoction of the root powder taken for rheumatoid arthritis. Bark powder mixed with butter applied as a remedy for swelling [71] |

| Solanaceae |

|

|

Bad spirits (Satan beshita) |

Adaptogen: whole system |

F1 |

“Gizawa is an all-out treatment for the whole system” |

|

| |

|

|

Evil eye (buda) |

|

F1 |

“Gizawa is like salt, it can go with anything. For devil spirit, epilepsy, buda. Not for wounds or physical sickness.” |

Evil spirit exorcism, joint infection, arthritis, malaria [12] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chest pain, mich, typhoid, evil eye [68] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M8, PH |

Old saying: “Why did your child die if you had Gizawa growing in your garden?” |

Narcotic properties. Decoctions are used as pain killers [46] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Main actions: Adaptogen, antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal, anti-inflammatory, chondroprotective, anticancer, anxiolytic and antidepressant [72] |

|

Zehneria scabra Sond. |

Hareg resa/Shahare |

1954 |

Dandruff (forefore) |

|

F2 |

|

Amenorrhoea, intelligence boost, mich (fever with headache) [12] |

| Cucurbitaceae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Eye problem (possibly trachoma) |

The eyelid is peeled back and rubbed with the back of the leaf. The eyes should be covered and protected from the light until healed. |

F1, M8 |

“The women use it” |

Mich (fever with headache), stomach ache, wart [49] |

| |

|

|

|

|

M8 |

|

Leprosy, wound dressing, measles, anthelmintic [73] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mich [28] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malaria [29] |

|

Zingiber officinale Roscoe. |

Zingibil |

|

Taeniasis |

As part of formula with Kosso (see Hagenia abyssinica) |

F1 |

|

Widely used as a medicinal plant worldwide |

| Zingiberaceae | Unexplained stomach ache (megagna) | As part of formula with Ariti (see Artemisia absinthium) and Tenadam (see Ruta chalepensis) | M3 |

Code: M = Male; F = Female; PH = Professional herbalist; E = Ethnobotanist.

Each informant contributed information about the herbs with which they were particularly familiar. Because discussions were allowed to flow in an unstructured way, this did not lead to a fidelity rating for all the herbs as agreement was not specifically sought from each informant on any one herb and no prompts were given. The two occasions where there was significant consensus on use of herbs for specific diseases was in the discussion of herbs for taeniasis and the discussion of the use of Calpurnia aurea for childhood diarrhoea (see Safety).

How herbal knowledge was acquired

All of the informants (15) described memories of being treated with herbs for illness as a child. All said they subsequently continued to learn, either from parents or knowledgeable elders, or both (see Table 4)

Table 4.

How herbal knowledge was acquired

| Informant | Exposed to treatment as child | Learnt from both parents | Learnt only from mother | Learnt only from father | Learnt from others* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female |

6 |

3 |

|

2 |

1 |

| Male |

9 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| TOTAL | 15 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

*Others learnt from include “relatives”, “grandmother”, “nun”, “people around the church”.

The two males who had learnt from both parents said that they had learned more from their fathers. One male who learnt only from his mother said that his father had died when he was young. The professional herbalist had learned from both his grandfather (a priest) and his mother.

Awareness of loss of herbs

There was recognition that some herbs are becoming less accessible, in part due to land degradation and accessibility. When the professional herbalist raised this issue during focus group 2, there was agreement from all present (6 men and 3 women). Examples of comments are:

“In the old days herbs were everywhere around the house and in the backyard because people planted them, and also they were growing naturally (referring to the observation in the past that herbs were tolerated or encouraged to grow around human habitation). Now I have to travel for two days to find some herbs. Even in the forest areas, some don’t exist any more at all…Now everyone is looking for herbs, but no-one plants and looks after them” (PH)

“There is degradation of land, deforestation. Marginally the herbs are still available” (F4)

“Initially the Set eret (Aloe pulcherrima) was found close by, but now it is difficult to find this plant, it is only in inaccessible areas now” (M6)

Conservation of herbs

Informants demonstrated an understanding of conservation practices in their wildcrafting of the herbs. When Aloe pulcherrima plants were dug up during a field-walk/discussion session (W4), the underground stems were planted for future growth, and an informant helping with collection and identification said:

“We don’t want to take the whole plant because we use that to keep it growing here” (M5)

In a focus group session (FG1), conservative practices were referred to by the professional herbalist:

“Some use six herbs for this [formula]. This means more uprooting of plants. I will use only three herbs for this, that means fewer plants used” (PH)

Passing on knowledge

Following a discussion as to whether the younger generation is less likely to be interested in learning about herbal medicine, some informants underscored this issue with their own family experience:

“Of my 29 children, four (male priests) have been taught. Two of the children of the priests are interested, two are not” (PH)

“I have five children. If they are interested, I will pass it on” (M3)

Community awareness of the threat to the future of traditional herbal medicine has been noted elsewhere in Ethiopia [14].

It has been stated that the younger generation in Ethiopia is increasingly losing interest in learning about the herbs [13,29]. However three children (boys between seven and ten years of age) who joined the field-walk/discussion activities offered some information about the herbs they saw. A nine-year-old boy who worked as a shepherd at the site of a field-walk/discussion excursion, demonstrated in-depth knowledge including recognition and use of medicinal herbs. He was the son of an informant considered a skilled herbalist. The fact that these boys were children of informants, who were knowledgeable about the herbs and used them medicinally, meant that they were more likely to have been exposed to herbal lore in the family setting.

With the possible exception of some herbal medicine education included in religious instruction (there are some known ancient texts held by the Church), due to illiteracy or lack of time, recipes or formulae for herbal treatments continue to be taught to family members solely by demonstration and practical use in the oral tradition of their antecedents.

There is a frequently stated understanding that secrecy is an obstacle to the sharing of knowledge, particularly in the domain of the predominantly male professional herbalists [4,68,74]. In contrast to this, and perhaps reflecting increased awareness of the potential for loss, the professional herbalist at Fiche was keen to be involved and fully supported the Botanica Ethiopia objectives of establishing herbal gardens (Additional file 2), contributing and encouraging discussion and collaboration. When the purpose of the research was explained, he said:

“Teruneew. (It is good). This must happen. What we are doing is important for the herbs”

Another professional herbalist in the area later supported this statement during a spontaneous conversation. The fact that both herbalists were supportive of the establishment of a community “healing herbs” Association as part of the Botanica Ethiopia initiative, with one of the herbalists becoming Deputy Chairperson of the Association, firmly demonstrated willingness to participate in sharing knowledge.

Safety

All participants showed awareness of safety issues and dosage importance.

The importance of safety was discussed in relation to dosages of herbs used for contraception, for children, and with herbs known to have strong activity against taeniasis (tapeworm infection). A focus group debate (FG3) centred on the use of the herb Phytolacca dodecandra (Endod) for contraceptive purposes.

“I gave this to my wife and she never fell pregnant again. Once you take it you are sterile for life” (M5)

“If you spray poison on a flower, it will die” (F1)

Discussions of herbs used for taeniasis showed consensus in the use of certain herbs (FG1, FG2 and FG3), but debate arose around safety in combining the herbs (FG2). Taeniasis is an epidemic infection in Ethiopia, largely due to the custom of eating raw meat [75]. The discussions focused on four herbs: Glinus lotoides (Meterre), Embelia schimperi (Enkoko), Albizia anthelmintica (Musena) and Hagenia abyssinica (Kosso) with Guizotia abyssinica (Nug) used as a binder to make a paste with the other herb(s). Informants were concerned about the potential for these herbs to cause toxicity and debated the merits of combining what they described as potent herbs. Each of the informants agreed that the four herbs mentioned were important, but there was disagreement as to whether they should be combined (considered dangerous by some) or used separately, and there were varying opinions on how the herbs should be taken. Table 5 summarises this discussion.

Table 5.

Discussion of herbs for taeniasis

|

Informant (M) = Male (F) = Female |

Local names and discussion | Botanical names |

|---|---|---|

| F1, F4, F5 |

Meterre with Nug |

Glinus lotoides + Guizotia abyssinica OR |

|

OR Musena with Nug |

Albizia anthelmintica + Guizotia abyssinica |

|

| The oil-containing Nug seed is ground to a paste and used to mix with the herbs for oral administration |

|

|

| F2 |

First preference is Kechemo |

Myrsine africana |

| If this does not work, then one of the following |

|

|

| a) Enkoko. Collect the ripe fruits, remove the outside and swallow the fruit directly using water |

Embelia schimperi |

|

| OR |

|

|

| b) Musena, the inflorescence, with Nug |

Albizia anthelmintica +Guizotia abyssinica |

|

| OR |

|

|

| c) Kosso, the inflorescence with Nug |

Hagenia abyssinica + Guizotia abyssinica |

|

| FI |