Abstract

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of allergic asthma by orchestrating and perpetuating airway inflammation and remodeling responses. In this study, we evaluated the IL-17RA signal transduction and gene expression profile in ASM cells from subjects with mild asthma and healthy individuals. Human primary ASM cells were treated with IL-17A and probed by the Affymetrix GeneChip array, and gene targets were validated by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Genomic analysis underlined the proinflammatory nature of IL-17A, as multiple NF-κB regulatory factors and chemokines were induced in ASM cells. Transcriptional regulators consisting of primary response genes were overrepresented and displayed dynamic expression profiles. IL-17A poorly enhanced IL-1β or IL-22 gene responses in ASM cells from both subjects with mild asthma and healthy donors. Interestingly, protein modifications to the NF-κB regulatory network were not observed after IL-17A stimulation, although oscillations in IκBε expression were detected. ASM cells from subjects with mild asthma up-regulated more genes with greater overall variability in response to IL-17A than from healthy donors. Finally, in response to IL-17A, ASM cells displayed rapid activation of the extracellular signal–regulated kinase/ribosomal S6 kinase signaling pathway and increased nuclear levels of phosphorylated extracellular signal–regulated kinase. Taken together, our results suggest that IL-17A mediated modest gene expression response, which, in cooperation with the NF-κB signaling network, may regulate the gene expression profile in ASM cells.

Keywords: IL-17RA, signal transduction, gene expression, airway smooth muscle cells

Clinical Relevance

IL-17A is key cytokine involved in many airway diseases, including asthma. Identifying the gene response of IL-17 in airway smooth muscle cells may pave the way to identifying critical pathways for targeting airway remodeling.

IL-17 plays an important and protective role in host defense by promoting the expansion, mobilization, and activation of neutrophils in response to extracellular pathogens (1). Effector functions of IL-17 include granulopoiesis, neutrophil recruitment via CXC-chemokines, and the production of antimicrobial proteins for the clearance of pathogens (2). T helper (Th) 17–associated cytokine IL-22 is also indispensable for the control of bacterial infections, as it acts on the epithelium in synergy with IL-17A to up-regulate crucial host defense genes (3). IL-17A has also been demonstrated to orchestrate airway inflammation by cooperating with and inducing proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, granulocyte colony–stimulating factor and CXC-chemokines from epithelial, fibroblast, vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells (4). Of note, the IL-17R signal transduction pathway mediates synergistic responses to TNF, Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, IL-1β and IL-22 via a TNF receptor–associated factor (TRAF)-2/5–splicing factor-2 signaling mechanism regulating mRNA stability (5–7). In our study, we aimed to further characterize the IL-17RA signal transduction pathway by identifying downstream mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), regulatory NF-κB kinases, and the gene expression profile induced by IL-17A in human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells.

Dysregulated IL-17 and Th17 responses can promote chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis (8). In the airways, increased levels of IL-17A and the presence of neutrophils are associated with chronic inflammatory disorders, such as cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma (9). Of note, sputum levels of IL-17A correlates with the severity of airway hypersensitivity (9) and IL-17A immunoreactive cells have been observed within smooth muscle bundles and in the airway lumen of patients with moderate to severe asthma (10). ASM cells regulate the bronchomotor tone and modulate airway inflammation by secreting cytokines, growth factors, and matrix proteins, and by expressing cell adhesion and costimulatory molecules (11). Notably, activated CD4+ CD25+ CD134+ T cells have been demonstrated to directly interact with myocytes during the infiltration of the airway wall in an experimental model of allergic asthma (12–14). Alveolar macrophages were also recently identified as a central source of IL-17A in asthmatic airways, and were observed to mediate acute pulmonary inflammation via the release of IL-1β (15, 16). Inducible natural killer cells, which coexpress IL-17A and IL-22, were also observed to mediate ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (17). Taken together, we hypothesized that IL-17A, in cooperation with local cytokines, may trigger effector functions in ASM cells, which contributes to, or exacerbates, airway inflammation.

In this study, we observed that the majority of the genes up-regulated by IL-17A 2 hours after stimulation were transcriptional regulators consisting mainly of primary response (PR) genes. IL-22 also up-regulated IL-17A gene targets, but similarly to IL-1β, the addition of IL-17A did not induce synergistic responses. IL-17A activated a distinctive gene subset in ASM cells from individuals with mild asthma, and included proinflammatory genes, such as Il6 and Cxcl10. IL-17A also induced the phosphorylation of the extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK)/ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK), c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and the 70-kD ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K). The combination of IL-17A with IL-1β increased nuclear levels of phosphorylated ERK. Despite up-regulating several NF-κB–dependent genes involved in the negative feedback of NF-κB, IL-17A was not observed to activate markers of the IκB-regulatory network unless combined with IL-1β. Taken together, our observations suggest that IL-17A up-regulates PR genes, which, in cooperation with the NF-κB signaling network, may regulate the IL-17A gene expression profile in ASM cells.

Materials and Methods

Bronchial Human ASM Cells

In accordance with procedures approved by the Research Ethics Committees of King’s College Hospital and the Human Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba, bronchial human ASM cells were obtained by deep endobronchial biopsy from the right middle or lower lobe bronchi of three healthy (methacholine provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1 > 16 mg/ml; FEV1 = 104 ± 1%; mean age, 31 ± 8 yr; two males, one female) and three glucocorticoid-naive subjects with mild atopy and asthma (methacholine provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1 = 0.52 ± 0.59 mg/ml; FEV1 = 84 ± 6%; mean age, 31 ± 3 yr; three males) volunteers (Table 1). Smooth muscle bundles were isolated from surrounding tissue using fine needles. Cells were grown by explant culture from ASM bundle fragments using methods described previously (18, 19). Fluorescent immunocytochemistry confirmed that near-confluent, FBS-deprived cells stained positive for smooth muscle–specific α-actin, desmin, and calponin (>95%). For the antibody profiling array and Western blot assays, immortalized human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) ASM cells were used as previously described (20). For all experiments, human ASM cells were used between passages 3 and 5. Unless stated otherwise, all other reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (Oakville, ON, Canada).

Table 1:

Donor Clinical Information: Human Bronchial Biopsies Were Abstracted from Six Patients between the Ages of 25 and 40 Years

| |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Sex | (Yr) | Smoker | Status | FEV1 | FEV1% Pred | PC20 | Therapy | Atopy | Allergen |

| 1 | M | 40 | ES | Healthy | 5.03 | 131 | >16 | — | No | — |

| 2 | M | 24 | NS | Healthy | 3.95 | 82 | >16 | — | No | — |

| 3 | F | 31 | NS | Healthy | 3.69 | 105 | >16 | — | No | — |

| 4 | M | 31 | NS | Asthmatic | 3.85 | 85 | 0.41 | Sal | No | — |

| 5 | M | 30 | NS | Asthmatic | 4.46 | 89 | 1.34 | Sal | Yes | Cat |

| 6 | M | 33 | NS | Asthmatic | 3.35 | 78 | 0.25 | Sal | Yes | Cat, HDM |

Definition of abbreviations: ES, ex-smoker; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1% Pred, percentage of predicted FEV1; HDM, house dust mite; NS; nonsmoker; PC20, provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1; Sal, salbutamol.

Cell Culture and Western Blot

As previously described, confluent human ASM cells were growth-arrested by FBS-deprivation for 48 hours in DMEM media and were stimulated in fresh FBS-free media with or without recombinant human IL-17A (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or IL-22 (10 ng/ml) (20). Recombinant human IL-17A and IL-22 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and IL-1β was purchased from PeproTech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). Cell extracts were collected by the M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) supplemented with the complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Bioscience, Laval, PQ, Canada). Western blotting was performed following standard laboratory procedures. Anti-human phosphorylated and total protein antibodies against p38, ERK, stress-activated protein kinase/JNK, phospho-IκB kinaseα/β, IkBα, IkBβ, IkBε, p65, p50, and secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against IL-17R, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activator 1 (ACT-1), TRAF6, and TGF-β activated kinase were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and H3 were obtained from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Human proteome profiler phospho-MAPK antibody array kit was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Optical band density was captured with a Fluorchem 8,800 Imaging System, AlphaEase FC software v3.1.2 (Alpha Innotech Corp., Santa Clara, CA) and integrated density values were determined using ImageJ v1.45 processing software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Gene Expression Array

IL-17A–induced transcripts were collected 2 hours after stimulation from primary human ASM cells of three subjects with mild asthma and three healthy normal donors. Total RNA was extracted by the RNeasy method (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada), and RNA purity and integrity was evaluated by electrophoretic trace with the Agilent 2,100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Technical and platform-specific procedures for the genome-wide, DNA-based whole transcript sense target Affymetrix HuGene v1.0 GeneChip were contracted to the University Health Network Microarray Centre Affymetrix Service (Toronto, ON, Canada). Quality control metrics were evaluated by the Affymetrix Expression Console software v1.1.1, and expression data were normalized by the Robust Multichip Analysis algorithm. Statistical analysis, data visualization, and gene annotation searches were performed with the Partek Genomics Suite v6.3 (St. Louis, MO), MultiExperiment Viewer v4.4.1 (Boston, MA), and Bioconductor v2.3 and Ingenuity Pathways Analysis v7.6 (Redwood City, CA) software. In compliance with Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME) guidelines, the microarray dataset was deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE35643. Functional annotation and gene classification analysis were performed with the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery v2008 Web-based program, as listed on the Gene Ontology website (21).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

Confluent primary human ASM cells were growth arrested for 48 hours by FBS deprivation and were stimulated for 2 and 6 hours in fresh FBS-free media containing IL-17A (10 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-22 (10 ng/ml), or vehicle. Total RNA was purified using the Qiagen RNeasy kit. Relative levels of mRNA were assessed with the ABI 7,500 Real-Time PCR System (ABI, Foster City, CA). Product specificity was determined by melting curve analysis, and calculation of the relative amount of each cDNA species was determined by the ΔΔ cycle threshold method. The amplification of target genes in stimulated cells was normalized to the respective glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels, and results are presented as fold increases over unstimulated controls. Primers were purchased from TIB Molbiol (Adelphia, NJ) and are listed in Table E1 in the online supplement.

Results

IL-17A Activates the Expression of NF-κB Regulatory Factors

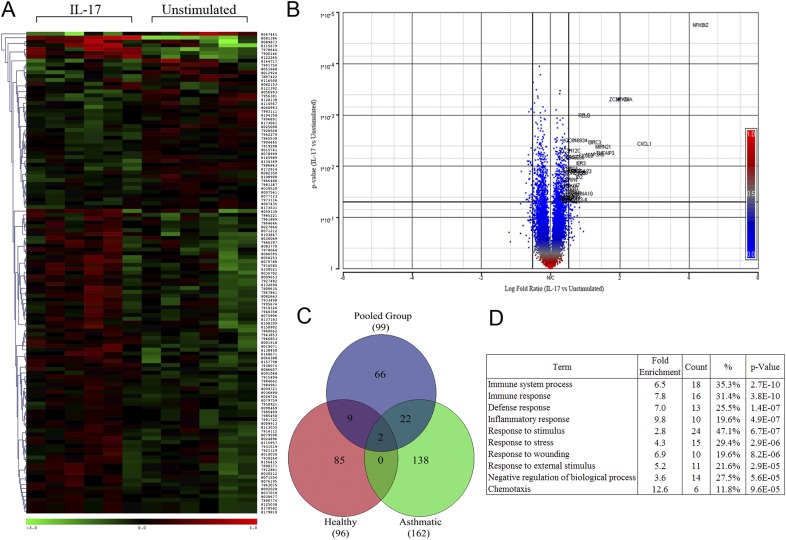

To evaluate IL-17A–inducible gene transcripts, primary human ASM cells from three subjects with mild asthma and three healthy donors were treated for 2 hours with IL-17A (10 ng/ml) and probed with the Affymetrix GeneChip array. The 2-hour time point was carefully chosen to identify PR gene targets and avoid confounding autocrine mechanisms mediating indirect or late-phase gene expression responses. Results from all subjects were pooled to uncover a common subset of genes mediated by IL-17A, irrespective of the health status. Statistical analysis identified 99 gene targets that were significantly up-/down-regulated (P ≤ 0.05, fold ≥ or ≤ 1.2; Figures 1A–1C), including several NF-κB regulatory factors, transcriptional regulators, and chemokines, as listed in Table 2. IL-17A mediated a modest fold increase in gene expression whereby four genes achieved approximately greater than twofold increases over unstimulated controls (Nfkbiz > Cxcl1 > Nfkbia > Zc3 h12a; Figure 1B). Gene ontology analysis revealed that the majority of the up-regulated genes largely localized in the cytoplasm and nuclear regions, and were mainly categorized as a response to stimulus and immune system process. Transcriptional regulators represented the greatest fraction of gene function, whereas chemotaxis and inflammatory response genes represented the greatest fold induction categories (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

IL-17A–inducible gene targets in primary human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells. (A) Heat map of significantly up-/down-regulated genes 2 hours after IL-17A stimulation in primary human ASM cells from six independent donors (P ≤ 0.05, fold ≥, ≤ 1.15). (B) Volcano plot demonstrating the distribution of gene expression (log2 fold) and probability values of IL-17A–stimulated cells over unstimulated conditions (P ≤ 0.05, fold ≥ 1.2). (C) Comparative analysis of significantly up-regulated genes from the pooled group versus those of the group of individuals with mild asthma and the healthy group (P ≤ 0.05, fold ≥ 1.15). (D) Functional annotation of IL-17A–induced biological processes of significantly up-regulated genes by IL-17 (P ≤ 0.05, fold ≥ 1.2).

Table 2:

IL-17A Gene Targets in Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cells from All Subjects

| P Value | Fold | Entrez ID | Name | Description | Location | Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.000 | 4.48 | 64,332 | NFKBIZ* | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, zeta | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 2 | 0.000 | 1.98 | 80,149 | ZC3H12A* | Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12A | Unknown | Other |

| 3 | 0.000 | 2.08 | 4,792 | NFKBIA | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, alpha | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 4 | 0.001 | 1.40 | 5,971 | RELB | V-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog B | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 5 | 0.003 | 1.55 | 330 | BIRC3 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| 6 | 0.003 | 2.55 | 2,919 | CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha) | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| 7 | 0.005 | 1.21 | 85,463 | ZC3H12C* | Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12C | Unknown | Other |

| 8 | 0.005 | 1.72 | 7,128 | TNFAIP3* | TNF-α–induced protein 3 | Nucleus | Other |

| 9 | 0.006 | 1.55 | 1,326 | MAP3K8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 | Cytoplasm | Kinase |

| 10 | 0.006 | 1.41 | 2,920 | CXCL2 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| 11 | 0.006 | 1.25 | 54,897 | CASZ1 | Castor zinc finger 1 | Nucleus | Enzyme |

| 12 | 0.008 | 1.35 | 8,870 | IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 13 | 0.011 | 1.22 | 79,165 | LENG1 | Leukocyte receptor cluster member 1 | Unknown | Other |

| 14 | 0.012 | 1.27 | 6,648 | SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| 15 | 0.012 | 1.26 | 6,236 | RRAD | Ras-related associated with diabetes | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| 16 | 0.012 | 1.24 | 4,791 | NFKB2 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 2 (p49/p100) | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 17 | 0.015 | 1.33 | 3,398 | ID2 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 2, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 18 | 0.024 | 1.21 | 83,940 | TATDN1 | TatD DNase domain containing 1 | Unknown | Other |

| 19 | 0.029 | 1.24 | 874 | CBR3 | Carbonyl reductase 3 | Cytoplasm | Enzyme |

| 20 | 0.030 | 1.22 | 6,348 | CCL3 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | Extracellular space | Cytokine |

| 21 | 0.032 | 1.27 | 3,383 | ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | Plasma membrane | Transcription regulator |

| 22 | 0.035 | 1.22 | 14,6850 | PIK3R6 | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit 6 | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 23 | 0.039 | 1.20 | 4,616 | GADD45B | Growth arrest and DNA-damage–inducible, beta | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 24 | 0.046 | 1.22 | 8,747 | ADAM21 | ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 | Plasma Membrane | Peptidase |

| 25 | 0.049 | 1.23 | 7,597 | ZBTB25 | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 25 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

Definition of abbreviations: ADAM, A disintegrin and metalloproteinase; BTB, born to bind; TatD, twin arginine translocation D.

Up-regulated genes 2 hours after IL-17 stimulation compared with unstimulated controls. Gene list is sorted on probability values (P ≤ 005 and F ≥ 12) and excludes genes not categorized by the National Center for Biotechnology Information RefSeq accession format as a mature transcript product (prefix NM).

Genes validated by quantitative RT-PCR.

IL-17A Differentially Activates Specific Gene Targets in ASM Cells of Individuals with Asthma

To investigate whether IL-17A activated a different gene expression profile in ASM cells of individuals with asthma, data from patients with a history of mild asthma (Table 1) were stratified from our gene array results. Principal component analysis demonstrated that the mean response to stimulation, based on the gene expression profile from subjects with mild asthma and healthy individuals, was moderately altered, but that the status of each group could be clearly differentiated. A total of 24 overlapping genes between the pooled group and the group of subjects with asthma (Figure 1C) were largely associated with proinflammatory processes and are partially listed in Table 3. Furthermore, IL-17A–stimulated ASM cells from individuals with asthma produced 1.7 times more significantly up-regulated genes (162 vs. 96 genes) than stimulated ASM cells from healthy individuals (Figure 1C). Of note, Nfkbiz and Pttg1 were the only two common transcripts listed between the groups, and Nfkbiz had the greatest fold increase over unstimulated controls in both the group of individuals with asthma (4.5-fold) and the healthy group (3.2-fold). A table of up-regulated genes sorted on probability values for healthy ASM cells is listed in Table E2.

Table 3:

IL-17A Gene Targets from Airway Smooth Muscle Cells from Individuals with Mild Asthma

| P value | Fold | Entrez ID | Name | Description | Location | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | 1.52 | 1326 | MAP3K8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 | Cytoplasm | Kinase |

| 0.003 | 1.22 | 26873 | OPLAH | 5-oxoprolinase (ATP-hydrolysing) | Unknown | Enzyme |

| 0.005 | 1.31 | 392376 | OR13C2 | Olfactory receptor, family 13, subfamily C, member 2 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.006 | 1.54 | 8870 | IER3 | Immediate early response 3 | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 0.007 | 1.20 | 55319 | C4ORF43 | Chromosome 4 open reading frame 43 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.007 | 1.24 | 337879 | KRTAP8-1 | Keratin-associated protein 8-1 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.008 | 1.78 | 80149 | *ZC3H12A | Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12A | Unknown | Other |

| 0.008 | 1.25 | 85376 | RIMBP3 | RIMS binding protein 3 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.009 | 1.42 | 127069 | OR2T10 | Olfactory receptor, family 2, subfamily T, member 10 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.009 | 1.24 | 338328 | GPIHBP1 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchored high density lipoprotein binding protein-1 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.009 | 1.20 | 343069 | HNRNPCL1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C-like 1 | Nucleus | Other |

| 0.010 | 4.52 | 64332 | *NFKBIZ | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 0.010 | 1.23 | 9232 | PTTG1 | Pituitary tumor-transforming 1 | Nucleus | Transcription regulator |

| 0.011 | 1.35 | 623 | *BDKRB1 | Bradykinin receptor B1 | Plasma Membrane | G-protein coupled receptor |

| 0.012 | 2.51 | 2919 | CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha) | Extracellular Space | Cytokine |

| 0.014 | 1.32 | 2162 | F13A1 | Coagulation factor XIII, A1 polypeptide | Extracellular Space | Enzyme |

| 0.015 | 1.34 | 3569 | *IL6 | Interleukin-6 (interferon, beta 2) | Extracellular Space | Cytokine |

| 0.016 | 1.26 | 4057 | LTF | Lactotransferrin | Extracellular Space | Peptidase |

| 0.017 | 1.40 | 3627 | CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | Extracellular Space | Cytokine |

| 0.017 | 1.22 | 4033 | LRMP | Lymphoid-restricted membrane protein | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 0.018 | 1.33 | 7100 | TLR5 | Toll-like receptor 5 | Plasma Membrane | Transcription regulator |

| 0.019 | 1.96 | 4792 | *NFKBIA | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha | Cytoplasm | Other |

| 0.019 | 1.89 | 2920 | CXCL2 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | Extracellular Space | Cytokine |

| 0.020 | 1.40 | 390637 | LOC390637 | Chromosome 15 open reading frame 58 | Unknown | Other |

| 0.023 | 1.28 | 388531 | RGS9BP | Regulator of G protein signaling 9 binding protein | Unknown | Other |

Up-regulated genes 2 hours after IL-17 stimulation compared with unstimulated controls. Gene list is sorted on probability values (P ≤ 005 and F ≥ 12) and excludes genes not categorized by the National Center for Biotechnology Information RefSeq accession format as a mature transcript product (prefix NM); underlined genes are shared with the pooled group.

Genes validated by quantitative RT-PCR.

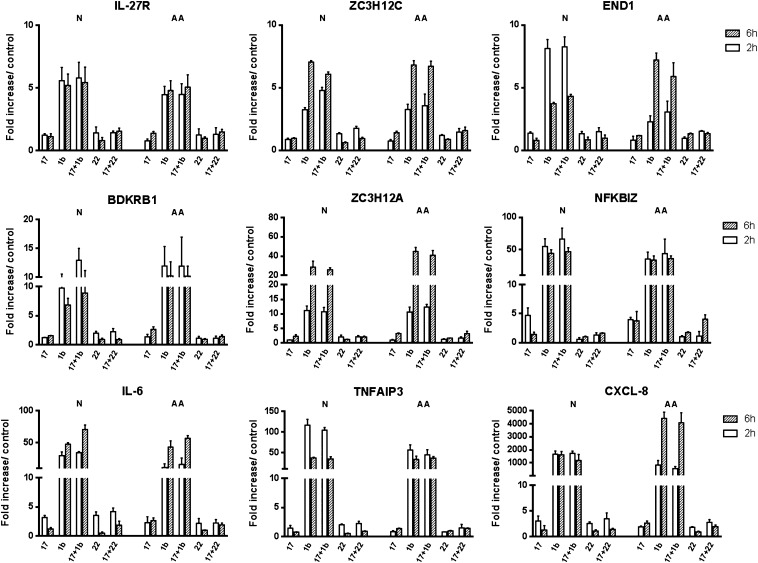

IL-17A Gene Targets Are Up-Regulated by IL-1β and IL-22

To validate the results from the GeneChip array, nine genes mediating various cellular functions, including previously reported IL-17A gene targets, were selected for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. IL-1β and Th17 cytokine IL-22 were included in the assay to assess whether IL-17A could mediate any additive or synergistic effect between the two cytokines. Our results demonstrate that, after 2 hours, analyzed transcripts were up-regulated by IL-17A and that Nfkbiz yielded the greatest fold increase in both ASM cells from healthy individuals and those with atopy and asthma (4.8 ± 1.4 fold vs. 3.9 ± 0.3, respectively; Figure 2). Of note, IL-17A did not significantly enhance IL-1β or IL-22 responses (Figure 2), conceivably due to the optimal cytokine concentrations used and to the short time point, which may not fully account for mRNA stability mechanisms (20, 22).

Figure 2.

Validation of IL-17A gene targets by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Response levels from nine genes selected from the GeneChip array analysis were confirmed in independent experiments by qRT-PCR. Synergistic responses between IL-17A and IL-1β or IL-22 (10 ng/ml) were equally assessed in primary human ASM cells from three individuals with atopy and asthma and three healthy, normal donors. Results were normalized to respective glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase levels, and are presented as the mean fold increase over unstimulated controls at 2 and 6 hours after cytokine stimulation.

To assess the dynamic gene expression profile induced by IL-17A, transcript levels from atopic asthmatic and healthy normal ASM cells were also analyzed 6 hours after stimulation. As previously reported for activating NF-κB ligands, such as TNF, LPS, and IL-1β, we observed distinct temporal trends where transcripts had either a sustained or an up-/down-regulated expression profile (23, 24). This effect was most notable in IL-1β–stimulated conditions where Zc3 h12a, End1, and Tnfaip3/A20 had the greatest divergent fold change in expression between 2 and 6 hours in cells from healthy donors (Figure 2). Expression levels in cells from individuals with atopy and asthma also revealed significant changes under IL-1β stimulation, such as for End1, Zc3 h12a, and Cxcl8. Conversely, IL-17A had minimal impact on the temporal expression profile induced by IL-1β, albeit increased levels of IL-6 at the 6-hour time point in cells from healthy donors. IL-22 elicited comparable gene expression responses to IL-17A, where Il6 and Cxcl8 had the greatest initial fold induction levels in cells from both individuals with atopy and asthma and healthy individuals.

IL-17A Is a Modest Activator of the NF-κB Regulatory Network

Based on our gene array results and on previous reports assessing the canonical NF-κB pathway in the IL-17R signal transduction, we investigated whether IκB proteins and kinases known to regulate the NF-κB pathway were activated by IL-17A. Although 15 NF-κB–dependent genes were up-regulated by IL-17A, which included regulatory members of the IκB family and Tnfaip3/A20 (Figure 2, Table E3), no observable change, with the exception of oscillating IκBε protein levels, was noted 1 hour after stimulation (Figure 3). In contrast, the combination of IL-17A with IL-1β decreased the expression of IκBα and slightly enhanced the nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 (Figures 3B and E1). Our results suggest that IL-17A poorly activates NF-κB regulatory factors, but can enhance the activating properties of IL-1β when added in combination.

Figure 3.

Activation state and synergistic response of the regulatory NF-κB network. Immortalized human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) ASM cells from three independent individuals were stimulated with IL-17A or IL-1β (10 ng/ml) (A) for up to 1 hour, or (B) in combination for 15 minutes. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were extracted and protein levels of NF-κB regulatory factors were assessed. C, cytoplasmic; IKK, IκB kinase; N, nuclear.

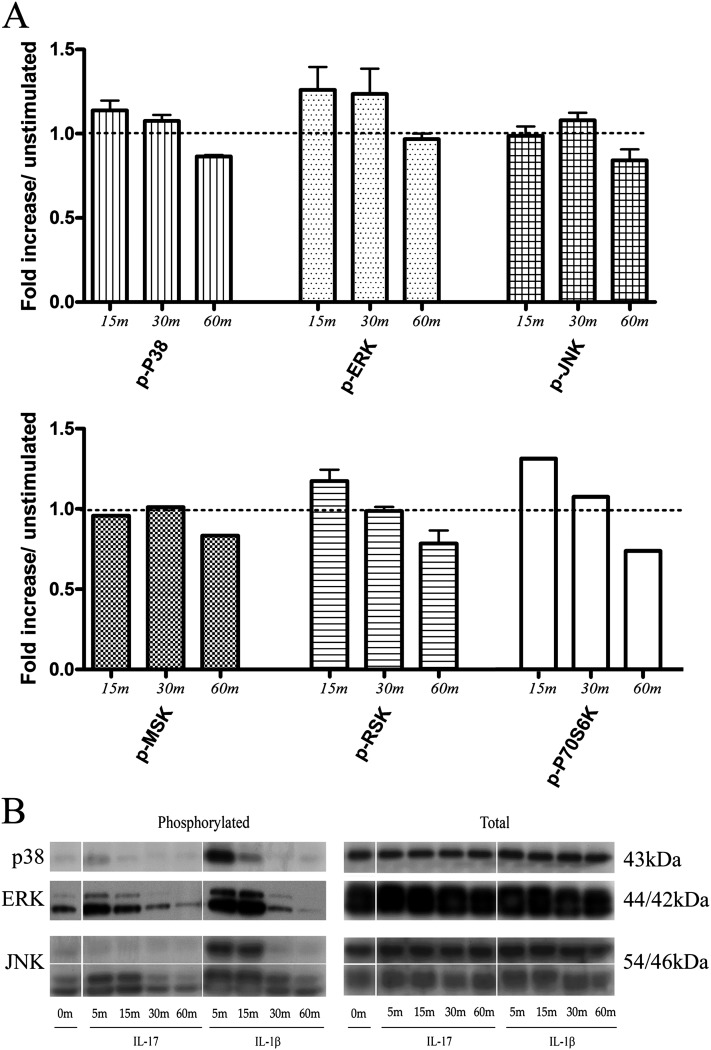

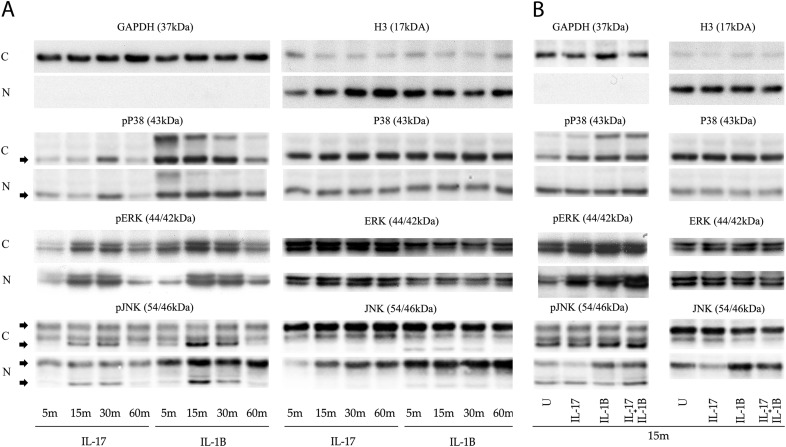

IL-17A Activates the ERK–RSK MAPK Pathway

To determine which kinases mediate the signal transduction pathway of the IL-17R, adaptor proteins, MAPKs, and downstream targets were probed by Western blotting methods. Phospho-MAPK array and conventional Western blots from ASM cells demonstrated robust ERK phosphorylation after stimulation with IL-17A and IL-1β (10 ng/ml) at 15 and 30 minutes (Figures 4 and 5). Subcellular Western blot analysis from fractionated extracts of human ASM cells further demonstrated an active role for ERK and JNK, as both phosphorylated kinases could be detected in the nucleus (Figure 5A). Notably, phosphorylated levels of ERK were significantly increased when combining IL-17A with IL-1β (Figures 5B and E2). In contrast, p38 activity was modest and transient. Interestingly, RSK1, a downstream target of ERK, was rapidly phosphorylated within 15 minutes of IL-17A stimulation in contrast to the mitogen and stress–activated protein kinase, a p38-ERK downstream homolog (Figure 4). Finally, expression levels of IL-17R and associated adaptor proteins, TRAF6, ACT-1, and kinase TAK1, were also measured and showed little variation, with the exception of TAK1, which migrated at a slightly higher molecular weight after IL-1β stimulation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway. Immortalized hTERT ASM cells from three independent individuals were stimulated with IL-17A or IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for up to 1 hour. (A) Profiling antibody array and validation by (B) Western blot was used to quantify MAPK kinases at 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after stimulation. ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; MSK, mitogen and stress–activated protein kinase; RSK, ribosomal S6 kinase.

Figure 5.

Nuclear translocation and synergistic response of MAPKs. Immortalized hTERT ASM cells from three independent individuals were stimulated with IL-17A or IL-1β (10 ng/ml) (A) for up to 1 hour, or (B) in combination for 15 minutes. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were extracted and MAPK levels were assessed.

Discussion

Previously, we demonstrated that IL-17A induced chemokine gene expression in human ASM cells (20, 25, 26). In this study, we investigated the IL-17RA signal transduction and gene expression profile in human ASM cells from individuals with mild asthma and healthy individuals. We observed that the gene expression profile of ASM cells stimulated with IL-17A from individuals with mild asthma contained significantly more up-regulated genes, such as Il6 and Cxcl10, in comparison to healthy donors. In response to IL-1β, ASM cells of individuals with atopy and mild asthma had lower expression levels of End1 and Tnfaip3/A20 at the 2-hour time point and up-regulated levels of End1 and Cxcl8 at the 6-hour time point (Figure 2). Comparative cluster analysis between the microarray gene lists for both groups revealed that 33 genes in the pooled group were mutually up-regulated in the healthy group or the group of individuals with asthma (Figure 1C). Although the remainder of the statistically up-regulated genes in the pooled group were not listed in either the healthy or asthma groups, doubling the population size to include values from both healthy and asthmatic ASM cells uncovered a subset of common genes, which had not achieve significance in either group alone. The poor overlap between the groups may be attributable to the fact that IL-17A induces modest gene expression levels at the 2-hour time point.

The recruitment of NF-κB to target promoters has been demonstrated to occur in two distinct waves: constitutively bound factors and nucleosome-free regions mediate the rapid induction of PR genes, whereas a late (≥ 4 h), nucleosomal modifying and/ or protein synthesis–dependent mechanism mediates the transcription of NF-κB–dependent secondary response (SR) genes (23, 27). Notably, nucleosome remodeling is required for the efficient recruitment of IκBζ to the transcriptional control regions of SR genes (28). Nfkbiz is a PR gene that localizes to the nucleus and triggers the induction of a subset of TLR- and IL-1–dependent, but not TNF-inducible, SR genes (29). Of Interest, Nfkbiz was previously reported to be up-regulated in response to IL-17A (30) and to platelet-derived growth factor (30). Mechanistically, IκBζ has a transcriptional activity domain that is constitutively suppressed by the ankyrin-repeat motif on the carboxy-terminal that is liberated when bound to the NF-κB p50 subunit (31). As such, NF-κB1 (p50)–deficient cells do not express IκBζ-dependent genes, such as Il6 and Il12b (29). In line with a regulatory role for IκBζ to mediate IL-17A–inducible SR genes, knockdown of IκBζ by small interfering RNA significantly diminishes hBD2 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells (30). Because IκBζ transcript levels decreased in response to IL-17 over time, IκBζ may be a selective coregulator of the NF-κB transcriptome, and may contribute to the specificity of the IL-17A response by coactivating SR genes.

The ZC3H12 protein family are TLR-, IL-1β-, and TNF-inducible genes containing a CCCH-type zinc-finger motif mediating RNase activity (32). Based on amino acid sequence alignment, ZC3H12 family members share homology with the tandem zinc-finger protein-36 (ZFP36) family, suggesting that the two groups may share functional features (33). ZFP36 (tristetraprolin) is an RNA-binding protein that suppresses inflammation by destabilizing and decreasing the half-life of mRNAs. Interestingly, ZFP36 was reported to suppress the transcriptional activity of NF-κB–dependent promoters by impairing the nuclear import of the p65 subunit in structural cells (34). Similarly, ZC3H12A was reported to negatively regulate NF-κB p65 promoter-binding activity and to destabilize the 3′ untranslated region of IL-6 mRNA, albeit not for Cxcl1, Cxcl10, Ccl5, or Nfkbia in murine macrophages (32, 35). Transfection of Zc3 h12a in endothelial cells up-regulated the expression of several CXC-chemokines and angiogenic factors, suggesting that ZC3H12A may regulate the expression of a subset of NF-κB–dependent genes (36). In line with a regulatory role for ZnF proteins to modulate the IL-17A gene profile, transcript levels of Zc3 h12a and Zc3 h12c increased 6 hours after stimulation with IL-17, and may be delayed to regulate SR genes by interacting with mRNA from NF-κB target genes.

NF-κB oscillations were previously proposed as a possible mechanism for IL-17A to mediate specificity in the gene expression profile (30). Inducible IκBε and IκBβ mediate the delayed removal of nuclear NF-κB and complement the rapid and strong feedback mechanism of IκBα (37). As such, delayed kinetics and ratios of inducible IκBα/β/ε can mediate nuclear NF-κB translocation dynamics and alter the gene expression profile (38). IκBδ (p100 homodimers) can also alter the activity of NF-κB (p50-RelA) in response to pathogen-triggered signals mediated by TLRs and alter the expression of SR genes, such as for CCL5 (39). Although IL-17A up-regulated mRNA levels of Ikbia, Ikbie, and Nfkb2 (p100) as observed in our gene array results, no post-translational modifications or nuclear translocation of IκB family members were observed by blotting methods other than for oscillating IκBε levels. In addition, we were unable to detect post-translational modifications to the IκB kinase-α/β after IL-17A stimulation. The difficulty in detecting any significant degradation products or post-translational modifications of regulatory NF-κB factors induced by IL-17A correlates with its poor ability to activate NF-κB (5, 22).

Activation of p38, ERK, and JNK by IL-17A in stromal cells has been previously demonstrated by immunoblotting and functional inhibitor assays (5). In ASM cells, p38 and ERK are both rapidly activated within 5 minutes, but express different activation profiles (26). p38 phosphorylation is transient and reported to mediate mRNA stabilization mechanisms (22, 40), whereas ERK phosphorylation is sustained, and mediates the activation of NF-κB and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (41). Activated ERK was also previously observed in the nucleus when combining IL-17A with TNF, which directly (or via downstream kinases, such as RSK) regulate transcription factors, coactivators, and nucleosomal proteins (42, 43). RSK has been demonstrated to mediate chromatin remodeling responses by phosphorylating histone (H)3 on serine (S)10, which recruits acetyltransferase complexes and activates the transcription of immediate-early genes (44). p70S6K, which we observed to be rapidly phosphorylated in response to IL-17A, also shares downstream targets with RSK, and has previously been reported to promote the assembly of the translation preinitiation complex (45). Of interest, RSK- and mitogen and stress–activated protein kinase-1–cAMP response element binding protein pathways have previously been demonstrated to mediate IL-17F signal transduction in normal human bronchial epithelial cells (46, 47). Our observations suggest that ERK-RSK and p70S6K kinases may play a key function in the IL-17R signal transduction, and that this pathway may mediate the nucleosome remodeling response required for gene transcription.

Taken together, our microarray analysis identified several PR genes induced by IL-17A that consisted largely of NF-κB regulatory factors, transcription regulators, and chemokines. IL-17A induced modest gene expression levels and poorly combined with IL-1β or IL-22 to enhance the gene expression response. IL-17A also up-regulated a distinctive proinflammatory gene expression profile in ASM cells of individuals with mild asthma, which may exacerbate airway inflammation. Collectively, our results suggest that IL-17A mediates a modest gene expression response and that the MAPK–NF-κB signaling network may regulate the IL-17A gene signature.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Andrew Halayko for providing the immortalized human telomerase reverse transcriptase airway smooth muscle cell line. They dedicate this article to the memory of their colleague, Dr. Stuart Hirst.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant MOP 53104 and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grant 386289-2011 (A.S.G.), and the Dr. Hadwen Trust and Asthma UK grant 07/034 (S.J.H.). S.D. is supported by a CIHR Canada Graduate Studentship.

Author Contributions: S.D. and A.S.G. conceived the study. S.D. and A.S.G. analyzed the data and S.D. drafted the manuscript. S.J.H., T.H.L., and A.S.G. contributed materials required for the study and provided key feedback on the study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0267OC on January 6, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Louten J, Boniface K, de Waal Malefyt R. Development and function of Th17 cells in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, Karim R, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M, Fouser LA. Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang YH, Liu YJ. The IL-17 cytokine family and their role in allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen F, Gaffen SL. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine. 2008;41:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zrioual S, Ecochard R, Tournadre A, Lenief V, Cazalis MA, Miossec P. Genome-wide comparison between IL-17A– and IL-17F–induced effects in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3112–3120. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun D, Novotny M, Bulek K, Liu C, Li X, Hamilton T. Treatment with IL-17 prolongs the half-life of chemokine CXCL1 mRNA via the adaptor TRAF5 and the splicing-regulatory factor SF2 (ASF) Nat Immunol. 2011;12:853–860. doi: 10.1038/ni.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nembrini C, Marsland BJ, Kopf M.IL-17–producing T cells in lung immunity and inflammation J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009123986–994.quiz 995–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ramli W, Prefontaine D, Chouiali F, Martin JG, Olivenstein R, Lemiere C, Hamid Q. T(h)17-associated cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1185–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazaar AL, Panettieri RA., JrAirway smooth muscle: a modulator of airway remodeling in asthma J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005116488–495.quiz 496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazaar AL, Albelda SM, Pilewski JM, Brennan B, Pure E, Panettieri RA., Jr T lymphocytes adhere to airway smooth muscle cells via integrins and CD44 and induce smooth muscle cell DNA synthesis. J Exp Med. 1994;180:807–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos-Barbon D, Presley JF, Hamid QA, Fixman ED, Martin JG. Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells drive airway smooth muscle remodeling in experimental asthma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1580–1589. doi: 10.1172/JCI19711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakonarson H, Kim C, Whelan R, Campbell D, Grunstein MM. Bi-directional activation between human airway smooth muscle cells and T lymphocytes: role in induction of altered airway responsiveness. J Immunol. 2001;166:293–303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakonarson H, Grunstein MM. Autocrine regulation of airway smooth muscle responsiveness. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;137:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song C, Luo L, Lei Z, Li B, Liang Z, Liu G, Li D, Zhang G, Huang B, Feng ZH. IL-17–producing alveolar macrophages mediate allergic lung inflammation related to asthma. J Immunol. 2008;181:6117–6124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, Zhu M, Iwakura Y, Savage PB, DeKruyff RH, et al. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gueders MM, Hirst SJ, Quesada-Calvo F, Paulissen G, Hacha J, Gilles C, Gosset P, Louis R, Foidart JM, Lopez-Otin C, et al. MMP-19 deficiency promotes tenascin-C accumulation and allergen-induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;43:286–295. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0426OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan V, Burgess JK, Ratoff JC, O’Connor BJ, Greenough A, Lee TH, Hirst SJ. Extracellular matrix regulates enhanced eotaxin expression in asthmatic airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:379–385. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragon S, Rahman MS, Yang J, Unruh H, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17 enhances IL-1beta–mediated CXCL-8 release from human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1023–L1029. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00306.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, Li X, Hamilton T. IL-17 enhances chemokine gene expression through mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 2007;179:4135–4141. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Two waves of nuclear factor kappaB recruitment to target promoters. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1351–1359. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.12.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Essen D, Engist B, Natoli G, Saccani S. Two modes of transcriptional activation at native promoters by NF-kappaB p65. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman MS, Yang J, Shan LY, Unruh H, Yang X, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17R activation of human airway smooth muscle cells induces CXCL-8 production via a transcriptional-dependent mechanism. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MS, Yamasaki A, Yang J, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Gounni AS. IL-17A induces eotaxin-1/CC chemokine ligand 11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of MAPK (ERK1/2, JNK, and p38) pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:4064–4071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tullai JW, Schaffer ME, Mullenbrock S, Sholder G, Kasif S, Cooper GM. Immediate-early and delayed primary response genes are distinct in function and genomic architecture. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23981–23995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702044200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayama H, Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, Yamamoto M, Mizutani T, Kuwata H, Iba H, Matsumoto M, Honda K, Smale ST, Takeda K. Class-specific regulation of pro-inflammatory genes by MYD88 pathways and IkappaBzeta. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12468–12477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto M, Yamazaki S, Uematsu S, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Kuwata H, Takeuchi O, Takeshige K, et al. Regulation of Toll/IL-1–receptor–mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IkappaBzeta. Nature. 2004;430:218–222. doi: 10.1038/nature02738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao CY, Kim C, Huang F, Wu R. Requirements for two proximal NF-kappaB binding sites and IkappaB-zeta in IL-17A-induced human beta-defensin 2 expression by conducting airway epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15309–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708289200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motoyama M, Yamazaki S, Eto-Kimura A, Takeshige K, Muta T. Positive and negative regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB–mediated transcription by IkappaB-zeta, an inducible nuclear protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7444–7451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsushita K, Takeuchi O, Standley DM, Kumagai Y, Kawagoe T, Miyake T, Satoh T, Kato H, Tsujimura T, Nakamura H, et al. ZC3H12A is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang J, Song W, Tromp G, Kolattukudy PE, Fu M. Genome-wide survey and expression profiling of CCCH-zinc finger family reveals a functional module in macrophage activation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schichl YM, Resch U, Hofer-Warbinek R, de Martin R. Tristetraprolin impairs NF-{kappa}B/p65 nuclear translocation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29571–29581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang J, Wang J, Azfer A, Song W, Tromp G, Kolattukudy PE, Fu M. A novel CCCH-zinc finger protein family regulates proinflammatory activation of macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6337–6346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niu J, Azfer A, Zhelyabovska O, Fatma S, Kolattukudy PE. Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 promotes angiogenesis via a novel transcription factor, MCP-1–induced protein (MCPIP) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14542–14551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802139200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kearns JD, Basak S, Werner SL, Huang CS, Hoffmann A. IkappaBepsilon provides negative feedback to control NF-kappaB oscillations, signaling dynamics, and inflammatory gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:659–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashall L, Horton CA, Nelson DE, Paszek P, Harper CV, Sillitoe K, Ryan S, Spiller DG, Unitt JF, Broomhead DS, et al. Pulsatile stimulation determines timing and specificity of NF-kappaB–dependent transcription. Science. 2009;324:242–246. doi: 10.1126/science.1164860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shih VF, Kearns JD, Basak S, Savinova OV, Ghosh G, Hoffmann A. Kinetic control of negative feedback regulators of NF-kappaB/rela determines their pathogen- and cytokine-receptor signaling specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9619–9624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henness S, van Thoor E, Ge Q, Armour CL, Hughes JM, Ammit AJ. IL-17A acts via p38 MAPK to increase stability of TNF-alpha–induced IL-8 mRNA in human ASM. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1283–L1290. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00367.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel DN, King CA, Bailey SR, Holt JW, Venkatachalam K, Agrawal A, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Interleukin-17 stimulates C-reactive protein expression in hepatocytes and smooth muscle cells via p38 MAPK and ERK1/2–dependent NF-kappaB and C/EBPbeta activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27229–27238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703250200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen RH, Sarnecki C, Blenis J. Nuclear localization and regulation of ERK- and RSK-encoded protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JW, Wang P, Kattah MG, Youssef S, Steinman L, DeFea K, Straus DS. Differential regulation of chemokines by IL-17 in colonic epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:6536–6545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merienne K, Pannetier S, Harel-Bellan A, Sassone-Corsi P. Mitogen-regulated RSK2-CBP interaction controls their kinase and acetylase activities. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7089–7096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7089-7096.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Li W, Williams M, Terada N, Alessi DR, Proud CG. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90(RSK1) and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 2001;20:4370–4379. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Huang SK, Homma T, Odaka M, Watanabe S, Suzuki S, Ieki K, Matsukura S, Kurokawa M, et al. The IL-17F signaling pathway is involved in the induction of IFN-gamma–inducible protein 10 in bronchial epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawaguchi M, Fujita J, Kokubu F, Huang SK, Homma T, Matsukura S, Adachi M, Hizawa N. IL-17F–induced IL-11 release in bronchial epithelial cells via MSK1-CREB pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L804–L810. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90607.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]