Abstract

An emerging tool in airway biology is the precision-cut lung slice (PCLS). Adoption of the PCLS as a model for assessing airway reactivity has been hampered by the limited time window within which tissues remain viable. Here we demonstrate that the PCLS can be frozen, stored long-term, and then thawed for later experimental use. Compared with the never-frozen murine PCLS, the frozen-thawed PCLS shows metabolic activity that is decreased to an extent comparable to that observed in other cryopreserved tissues but shows no differences in cell viability or in airway caliber responses to the contractile agonist methacholine or the relaxing agonist chloroquine. These results indicate that freezing and long-term storage is a feasible solution to the problem of limited viability of the PCLS in culture.

Keywords: precision-cut lung slice, cryopreservation, airway contractility, airway smooth muscle

Clinical Relevance

An emerging tool in airway biology is the precision-cut lung slice (PCLS). Adoption of the PCLS as a model for assessing airway reactivity has been hampered by the limited time window within which tissues remain viable. Here we demonstrate that freezing and long-term storage is a feasible solution to the problem of limited viability of the PCLS in culture.

In preclinical models of airway reactivity, responses to constrictor or relaxant agonists are typically assessed using the intubated and ventilated living animal, the isolated airway smooth muscle (ASM) strip, or the isolated ASM cell. Assessment in the living animal offers the advantage of studying the airway in its native microenvironment (1), but because responses of individual airways are innately and dramatically heterogeneous (2–5), inference of airway behavior is indirect, complex, and often ambiguous (6, 7) and is costly in terms of time and money. The ASM strip (8–10) or ASM cell (4, 11–13) isolated from trachea or major bronchi provides a direct and unambiguous assessment of muscle contractility, but results so obtained may not be representative of responses of muscle from smaller airways. Moreover, such preparations lack the mechanical and humoral microenvironment provided by parenchymal tethering and other cellular components of the airway wall in situ. Accordingly, these preparations of isolated tissues and cells comprise an important tool but are of equivocal physiological relevance (14).

An attractive new preparation for studying reactivity of the small airway is the precision-cut lung slice (PCLS) (15–24). Using the PCLS, airway narrowing can be assessed by direct microscopic observation of individual airways of any size. Although there is no alveolar air–liquid interface and lung recoil is therefore not faithfully maintained, the muscle microenvironment roughly approximates in situ conditions (15). Additional practical advantages of the PCLS include ease of preparation, widespread applicability to nearly every animal species including human (22, 25), and suitability for high-resolution imaging (19, 21). In the PCLS, even responses to neural stimulation (20, 23) and stretch (18, 22, 24) have been evaluated.

The use of the PCLS for assessment of airway responsiveness is limited by tissue viability in culture, which lasts 3 to 6 days from the time of tissue harvest (19). This limitation imposes scheduling difficulties and severely constrains the number of slices that can be studied per lung. To overcome limited tissue viability, we describe here a new approach to collect, preserve, and then study the PCLS. Using the conventional cryopreservative dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (26, 27), we demonstrate that murine PCLSs can be frozen, stored, and thawed for study of airway reactivity at a later time.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Lungs were obtained from seven 20-week-old C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). All animal procedures were approved by the Boston University IACUC Committee.

PCLS

Preparation and culture.

Each PCLS was prepared as described previously (17). After tracheotomy, excised mouse lungs were insufflated with 1% low-melting-point agarose in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). The insufflated lungs were then placed in cold HBSS (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA). After the agarose gelled, the left lower lobe was separated and sectioned into 250-μm-thick slices using a tissue slicer (VF-300; Precisionary Instruments, Greenville, NC). Lung slices were incubated at 37°C in 1:1 DMEM/F-12 supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, kanamycin, and amphotericin B (Invitrogen, Cambridge, MA). Culture medium was changed once an hour for the first 4 hours and once a day thereafter.

Freezing and thawing.

For cryopreservation, we used 10% DMSO diluted in Dulbecco's modified Eagle/F-12 medium. Each single PCLS was placed in cryopreservation medium in individual cryovials and frozen at −80°C (Nalgene Mr. Frosty Freezing Container; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tewksbury, MA). After overnight freezing, each cryovial was transferred to liquid nitrogen for storage for up to 2 weeks. On the day of the experiment, each cryovial was thawed rapidly in a 37°C water bath. The PCLS was then carefully removed and washed once in fresh culture medium.

Measurement of Cytotoxicity: Lactate Dehydrogenase–Releasing Assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-releasing assay was performed using the CytoTox 96 non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, PCLSs were incubated for 18 hours in culture medium at 37°C. The amount of LDH released into the culture supernatant was used to determine the number of dead cells. Using the culture supernatant, cell death was quantified using a standard ELISA for LDH implemented at an optical density of 490 nm (SpectraMax M5; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). These measurements were normalized to total number of cells in the PCLS that were obtained in a representative set through standard procedures of lysis and sonication.

Measurement of Cell Enzymatic Activity Using MTT

MTT was performed using a Vybrant MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, PCLSs were incubated for 3 hours in culture medium containing 500 ng/ml MTT. The culture medium was then replaced with 100% DMSO, and the amount of dissolved formazan was quantified by examining the supernatant at an absorbance of 540 nm.

Preparation and Immunohistology in Thin Sections of PCLS

Never-frozen and frozen-thawed PCLSs were fixed for 20 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS solution, washed with PBS, and immersed overnight in a 30% sucrose/PBS solution. The PCLSs were then embedded in optical cutting temperature compound and sectioned to 10-μm-thick slices. Using a previously established protocol (28), the slices were immunostained with antibodies against the lung epithelium marker CC10 (1:500, T-18; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and the ASM marker α-smooth muscle actin (1:500, MS-113; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Live/Dead Staining and Imaging

The viability of the PCLS was tested using a commercially available kit (LIVE/DEAD kit L-3224; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, the PCLS was stained with 4 mM calcein-AM and 2 mM ethidium homodimer-1 in HBSS with calcium and magnesium, incubated at 37°C for 30 to 45 minutes, and imaged on an inverted microscope using a green fluorescent protein filter (bandpass filter [BP] 470/40) for calcein-AM and a Cy3 filter (BP 545/30) for ethidium homodimer-1 (DMI6000B; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Measurements of Airway Contraction and Relaxation

Using a ring of nylon mesh and a metal washer, each PCLS was secured in place within a 12-well plate. The multiwell plate was mounted on a computer-controlled translation stage and imaged using an inverted microscope (DMI6000B; Leica Microsystems, ). Intact airways were selected for imaging, and PCLSs were incubated sequentially with increasing doses of methacholine (MCh) (10−7, 10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 minutes each followed by 1 mM chloroquine (ChQ) (Sigma Aldrich) for 10 minutes. Each airway was maintained in the same plane of focus and imaged every minute for a duration of 35 minutes. From the acquired images, we quantified airway luminal area (Image J software; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and normalized its magnitude to the pretreatment baseline value. From the normalized data, we picked values corresponding to maximum constriction with each dose of MCh and maximum dilation with ChQ.

Statistics

For reasons addressed in the Discussion, fractional changes of airway luminal area of never-frozen PCLSs (n = 57 airways) versus frozen-thawed PCLSs (n = 46 airways) were compared using a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank-sum test (3). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. All data are reported as mean and SEM.

Results

Freezing-Thawing Does Not Increase Cell Death or Compromise Tissue Integrity

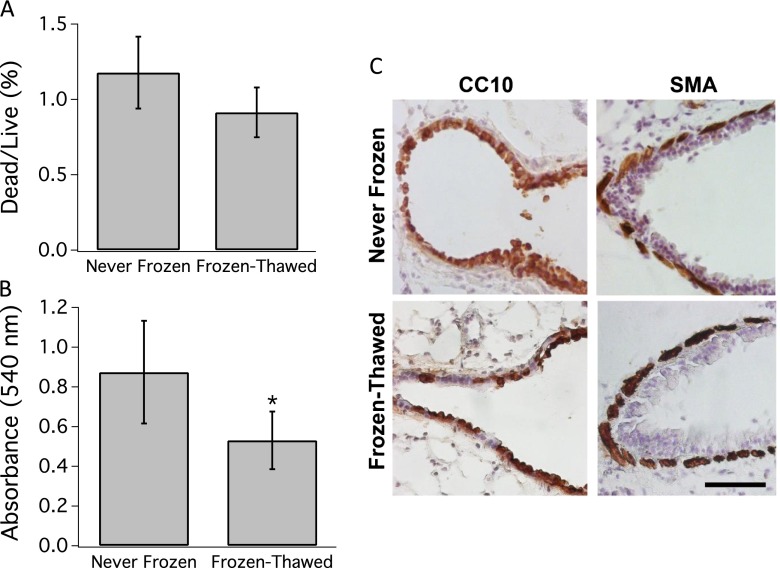

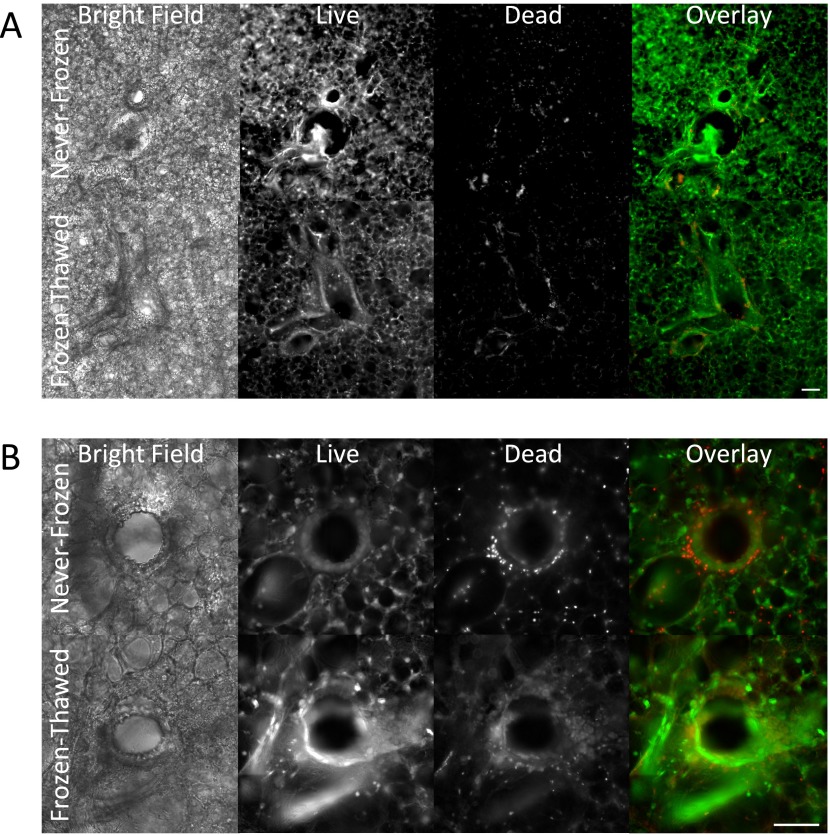

Ciliary beating in the airway epithelium was robust and qualitatively similar in never-frozen and the frozen-thawed PCLSs (see Video 1 in the online supplement). The LDH assay showed that cell death was slight (∼ 1%) and similar in the never-frozen and the frozen-thawed PCLSs (Figure 1A). The MTT assay showed that cell enzymatic activity was reduced in the frozen-thawed group (P < 0.05) (Figure 1B), but these changes fell well within the range previously reported for other cryopreserved tissues (29–31). Immunohistology of thin sections of the PCLS showed the airway epithelium and smooth muscle layers were intact to a similar extent in distal airways in never-frozen and frozen-thawed PCLSs (Figure 1C). Further microscopic observation showed that lung parenchyma, blood vessels, and airways of never-frozen and frozen-thawed PCLSs were structurally intact (Figures 2A and 2B). Associated cell death was minimal and predominantly localized along the edges of the PCLS and in the airway epithelium, although even there the vast majority of cells were alive (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 1.

Viability is preserved in frozen-thawed precision-cut lung slice (PCLS). (A) Lactate dehydrogenase assay shows no significant difference between frozen-thawed and never-frozen groups in the percentage of dead to live cells (n = 22 PCLSs in each group). (B) MTT assay showed a significant reduction in cell metabolic activity after freeze-thaw (*P < 0.05) but well within the acceptable range previously reported for other tissues. These data are reported as mean and standard deviation of formazan absorbance at 540 nm (n = 18 PCLSs in each group). (C) Images of distal airways from sections of never-frozen and frozen-thawed PCLSs immunostained for CC10 expression in the lung epithelium and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression in the airway smooth muscle. Cell nuclei were counterstained by hemotoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Figure 2.

Cell death in PCLS is minimal and predominantly localized to airway epithelium. (A) Representative bright field and florescence images of live-dead stained never-frozen or frozen-thawed PCLSs (original magnification: ×10). Scale bar = 200 μm. (B) Representative bright field and fluorescence images of live-dead stained never-frozen or frozen-thawed PCLSs (original magnification: ×20). Scale bar, 200 μm.

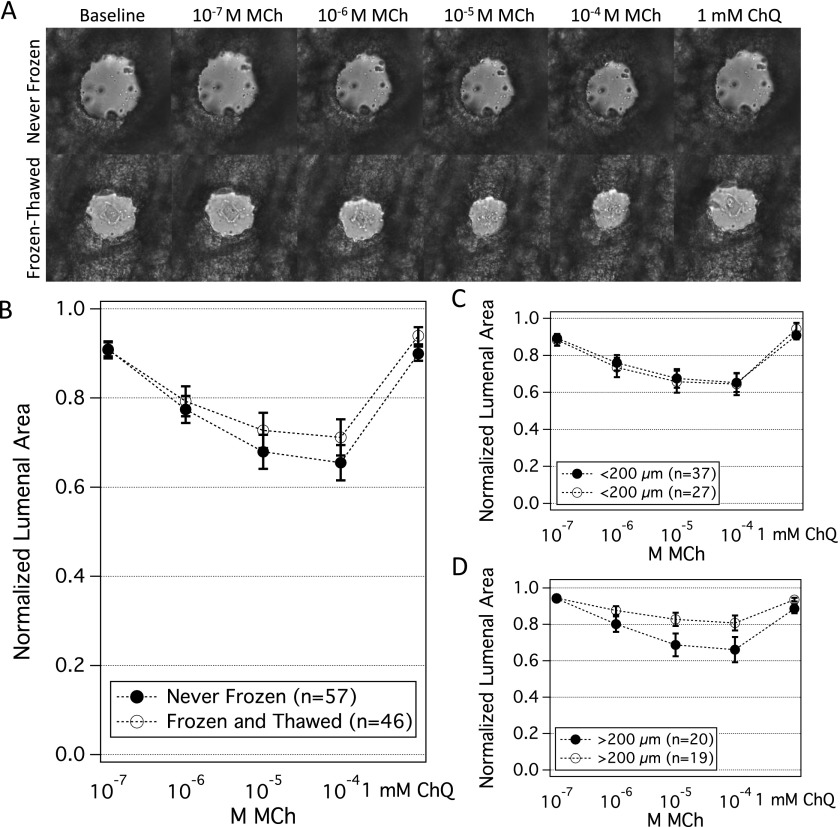

Freezing-Thawing Does Not Alter Contractile Response to MCh

In response to MCh (10−7 to 10−4 M), airway contractile responses in the never-frozen and the frozen-thawed groups were highly variable. These responses varied slightly with initial airway size, with smaller airways (< 200 μm) being more responsive (Figures 3C and 3D). Irrespective of initial airway size, contractile responses were not statistically different between the never-frozen and the frozen-thawed groups (P = 0.1–0.5) (Figures 3A–3D). For example, at 10−4 MCh, airway luminal area contracted to a mean value of 64 ± 9% (SEM) of the baseline in the never-frozen group (n = 57 airways), compared with a mean value of 69 ± 5% of baseline in the frozen-thawed group (n = 46 airways; P = 0.2). At a time resolution of 1 minute, we observed no differences in the rate of contraction with MCh between never-frozen and frozen-thawed airways (Figure E1). In addition, there was no significant difference in the values for half maximal effective concentration between the never-frozen and frozen-thawed groups (P = 0.24).

Figure 3.

Airway contractility is preserved in frozen-thawed PCLSs. In the never-frozen group, the mean diameter was 151 μm (range, 88–389 μm); in the frozen-thawed group, the mean diameter was 175 μm (range, 77–415 μm). (A) Representative images of airway contraction to methacholine (MCh) (10−7 to 10−4 M) and airway relaxation to chloroquine (ChQ) (1 mM) in the never-frozen and frozen-thawed groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) When pooled, airway contraction and relaxation in never-frozen (n = 57 airways) and frozen-thawed (n = 46 airways) PCLSs were not statistically different with MCh or ChQ (P = 0.2–0.4). Plotted are mean and SEM. (C, D) In both groups, individual airways contracted heterogeneously. To assess the role of initial airway size, we grouped airways into two bins: smaller than 200 μm (C) and larger than 200 μm (D). Within each airway size bin, never-frozen and frozen-thawed airways did not show significant differences in their responses to MCh and to ChQ (P = 0.1–0.5).

Freezing-Thawing Does Not Alter Relaxant Response to ChQ

To airways that were preconstricted with MCh, as described above, we administered the relaxant agonist ChQ (1 mM) (32). Relaxation responses were not statistically different between never-frozen and frozen-thawed groups (P = 0.21) (Figures 3A–3C). Airways relaxed to a mean of 90 ± 2% of the baseline in the never-frozen group (n = 57 airways) and to a mean of 94 ± 2% of the baseline in the frozen-thawed group (n = 46 airways). We also observed significant dilation in response to the relaxing agonist formoterol in airways from frozen-thawed PCLSs (Figure E2), which in pilot experiments was of a similar magnitude as observed in never-frozen PCLSs (data not shown).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate for the first time that it is possible to freeze and thaw the murine PCLS while maintaining unaltered responses to MCh and ChQ. Although cellular metabolic activity was somewhat reduced, cell death, ciliary beating, and airway narrowing were not appreciably affected. It remains unclear if this methodology might be useful to preserve nerve fiber endings, mast cells, or other receptor targets on ASM. These findings are of practical importance because the time window for measurement of airway responses in the never-frozen PCLS is limited to a few days (16, 19), whereas the time window for measurement in the frozen PCLS is demonstrated here to extend as long as 2 weeks.

Storage times substantially longer than 2 weeks are plausible because cryopreservation studies in other tissues typically find that the duration of storage does not appreciably affect viability (33–36), and in pilot studies we found no changes in airway contractility after 3 months. In slices of other organs, a variety of cryopreservation techniques have been used (26, 27, 37, 38), although airway contractile responses in general, and lung slices in particular, have never before been studied after cryopreservation. We used the conventional cryoprotectant DMSO and obtained satisfactory results using a high concentration. At this concentration, DMSO readily infiltrates the cell membrane, remains water-soluble even at low temperatures, and has low cytotoxicity (27). We chose a slow freezing rate of 1°C/min to prevent the formation of ice crystals inside cells. We chose a rapid thawing rate because pilot experiments showed less ciliary beating and more cell death in PCLSs that were thawed more slowly. These measurements were limited to 37°C, however, and do not preclude other conditions, including lower thaw temperatures. Ultimately, our method resulted in an average of 1% cell death in never-frozen and frozen-thawed PCLSs. The cell metabolic activity was significantly reduced in the frozen-thawed PCLSs but was well within the acceptable range previously reported for other tissues (29–31).

Innate biological variability of airway responsiveness across airways even within the same animal is quite large and does not follow a normal distribution (2, 3, 23). For example, Minshall and colleagues showed at the level of human lung slices that airway responses are remarkably heterogeneous even in the same lung donors (2). Even at the level of the underlying smooth muscle cell, cellular contractility and other cellular mechanical properties are known to be innately heterogeneous and distributed nonnormally, with geometric standard deviations of approximately 3 (4, 39–41). No factor of airway geometry can account for these non-Gaussian heterogeneities, which seem to be innate to the contractile units themselves. Accordingly, for statistical analysis of airway narrowing, we used the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

We found large variation in airway contractile response to MCh even for airways from the same animal, the same experimental condition, and the same initial size (Figures 3B–3D), consistent with earlier studies demonstrating innate biological heterogeneity of ASM contractility in tracheal smooth muscle strips, isolated ASM cells, and the human PCLS (2–5, 22, 42–44). Smaller airways were systematically more responsive, however. The airway narrowing that we observed was comparable in extent to recently published studies in the C57BL/6 mouse showing airway narrowing of approximately 40% with 10−4 M MCh, as compared with the 36% mean narrowing reported in our control at the same dose (45, 46).

To test the effects of cryopreservation on airways responsiveness, we used the contractile cholinergic agonist MCh and the dilating bitter tastant agonist ChQ. We chose ChQ because it causes a substantially greater bronchodilation in murine airways compared with β-agonists (32), and, as such, we reasoned that any differences in bronchodilation caused by cryopreservation would be made more apparent.

Together, the data reported here establish the frozen-thawed PCLS as a useful preparation for study of airway responsiveness. By freezing and storing the PCLS, timing of experiments becomes uncoupled from that of harvesting, and utilization of precious samples is maximized. It seems likely that similar results could be obtained using human tissues or genetically engineered laboratory animals, but this remains to be tested directly. Freezing and thawing thus makes feasible the notion of a PCLS bank and enables expanded use of this emerging ex vivo preparation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Quynh Dang and Kavitha Rajendran at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Dr. Mehmet Toner at Harvard Medical School, and Dr. Yan Bai and Dr. Linh Aven at Boston University School of Medicine for technical contributions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1R21HL112619 (A.F.), by a Parker Francis Foundation grant (R.K.), and by an American Asthma Foundation grant (X.A.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0166MA on December 6, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bates JH, Rincon M, Irvin CG. Animal models of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L401–L410. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minshall E, Wang CG, Dandurand R, Eidelman D. Heterogeneity of responsiveness of individual airways in cultured lung explants. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowther SD, Chapman ID, Morley J. Heterogeneity of airway hyperresponsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:606–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabry B, Maksym GN, Shore SA, Moore PE, Panettieri RA, Jr, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Selected contribution: time course and heterogeneity of contractile responses in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;91:986–994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King GG, Carroll JD, Müller NL, Whittall KP, Gao M, Nakano Y, Paré PD. Heterogeneity of narrowing in normal and asthmatic airways measured by HRCT. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:211–218. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00047503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tgavalekos NT, Musch G, Harris RS, Vidal Melo MF, Winkler T, Schroeder T, Callahan R, Lutchen KR, Venegas JG. Relationship between airway narrowing, patchy ventilation and lung mechanics in asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1174–1181. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00113606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tgavalekos NT, Tawhai M, Harris RS, Musch G, Vidal-Melo M, Venegas JG, Lutchen KR. Identifying airways responsible for heterogeneous ventilation and mechanical dysfunction in asthma: an image functional modeling approach. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005;99:2388–2397. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00391.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredberg JJ. Airway smooth muscle in asthma: perturbed equilibria of myosin binding. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S158–S160. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_2.a1q4-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredberg JJ, Jones KA, Nathan M, Raboudi S, Prakash YS, Shore SA, Butler JP, Sieck GC. Friction in airway smooth muscle: mechanism, latch, and implications in asthma. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996;81:2703–2712. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell ML, Lavoie TL, Lakser OJ, Dulin NO, Fredberg JJ, Gerthoffer WT, Seow CY, Mitchell RW, Solway J. MEK modulates force-fluctuation-induced relengthening of canine tracheal smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:630–637. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 2007;447:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An SS, Kim J, Ahn K, Trepat X, Drake KJ, Kumar S, Ling G, Purington C, Rangasamy T, Kensler TW, et al. Cell stiffness, contractile stress and the role of extracellular matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan R, Park CY, Lin YC, Mead J, Jaspers RT, Trepat X, Lenormand G, Tambe D, Smolensky AV, Knoll AH, et al. Reinforcement versus fluidization in cytoskeletal mechanoresponsiveness. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An SS, Bai TR, Bates JH, Black JL, Brown RH, Brusasco V, Chitano P, Deng L, Dowell M, Eidelman DH, et al. Airway smooth muscle dynamics: a common pathway of airway obstruction in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:834–860. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00112606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Held HD, Martin C, Uhlig S. Characterization of airway and vascular responses in murine lungs. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wohlsen A, Martin C, Vollmer E, Branscheid D, Magnussen H, Becker WM, Lepp U, Uhlig S. The early allergic response in small airways of human precision-cut lung slices. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:1024–1032. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00027502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai Y, Sanderson MJ. Modulation of the Ca2+ sensitivity of airway smooth muscle cells in murine lung slices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L208–L221. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00494.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dassow C, Wiechert L, Martin C, Schumann S, Müller-Newen G, Pack O, Guttmann J, Wall WA, Uhlig S. Biaxial distension of precision-cut lung slices. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;108:713–721. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00229.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanderson MJ. Exploring lung physiology in health and disease with lung slices. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlepütz M, Uhlig S, Martin C. Electric field stimulation of precision-cut lung slices. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110:545–554. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00409.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seehase S, Schlepütz M, Switalla S, Mätz-Rensing K, Kaup FJ, Zöller M, Schlumbohm C, Fuchs E, Lauenstein HD, Winkler C, et al. Bronchoconstriction in nonhuman primates: a species comparison. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:791–798. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00162.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavoie TL, Krishnan R, Siegel HR, Maston ED, Fredberg JJ, Solway J, Dowell ML. Dilatation of the constricted human airway by tidal expansion of lung parenchyma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:225–232. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0368OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlepütz M, Rieg AD, Seehase S, Spillner J, Perez-Bouza A, Braunschweig T, Schroeder T, Bernau M, Lambermont V, Schlumbohm C, et al. Neurally mediated airway constriction in human and other species: a comparative study using precision-cut lung slices (PCLS) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidovich N, Huang J, Margulies SS. Reproducible uniform equibiaxial stretch of precision-cut lung slices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304:L210–L220. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00224.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper PR, Panettieri RA., Jr Steroids completely reverse albuterol-induced beta(2)-adrenergic receptor tolerance in human small airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasper HU, Konze E, Kutinová Canová N, Dienes HP, Dries V. Cryopreservation of precision cut tissue slices (PCTS): investigation of morphology and reactivity. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2011;63:575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pegg DE. Principles of cryopreservation. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;368:39–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-362-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radzikinas K, Aven L, Jiang Z, Tran T, Paez-Cortez J, Boppidi K, Lu J, Fine A, Ai X. A Shh/miR-206/BDNF cascade coordinates innervation and formation of airway smooth muscle. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15407–15415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2745-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGowan I, Tanner K, Elliott J, Ibarrondo J, Khanukhova E, McDonald C, Saunders T, Zhou Y, Anton PA. Nonreproducibility of “snap-frozen” rectal biopsies for later use in ex vivo explant infectibility studies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1509–1512. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacRae JW, Tholpady SS, Ogle RC, Morgan RF.Ex vivo fat graft preservation: effects and implications of cryopreservation Ann Plast Surg 200452281–282.discussion 283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maas WJ, Leeman WR, Groten JP, van de Sandt JJ. Cryopreservation of precision-cut rat liver slices using a computer-controlled freezer. Toxicol In Vitro. 2000;14:523–530. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(00)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deshpande DA, Wang WC, McIlmoyle EL, Robinett KS, Schillinger RM, An SS, Sham JS, Liggett SB. Bitter taste receptors on airway smooth muscle bronchodilate by localized calcium signaling and reverse obstruction. Nat Med. 2010;16:1299–1304. doi: 10.1038/nm.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attarian H, Feng Z, Buckner CD, MacLeod B, Rowley SD. Long-term cryopreservation of bone marrow for autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson JO, Toner M. Long-term storage of tissues by cryopreservation: critical issues. Biomaterials. 1996;17:243–256. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85562-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riggs R, Mayer J, Dowling-Lacey D, Chi TF, Jones E, Oehninger S. Does storage time influence postthaw survival and pregnancy outcome? An analysis of 11,768 cryopreserved human embryos. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxe AW, Gibson GW, Kay S.Characterization of a simplified method of cryopreserving human parathyroid tissue Surgery 19901081033–1038.discussion 1038–1039 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Graaf IA, Draaisma AL, Schoeman O, Fahy GM, Groothuis GM, Koster HJ. Cryopreservation of rat precision-cut liver and kidney slices by rapid freezing and vitrification. Cryobiology. 2007;54:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Graaf IA, Koster HJ. Cryopreservation of precision-cut tissue slices for application in drug metabolism research. Toxicol In Vitro. 2003;17:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(02)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balland M, Desprat N, Icard D, Féréol S, Asnacios A, Browaeys J, Hénon S, Gallet F. Power laws in microrheology experiments on living cells: comparative analysis and modeling. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2006;74:021911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.021911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabry B, Maksym GN, Butler JP, Glogauer M, Navajas D, Fredberg JJ. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fabry B, Maksym GN, Butler JP, Glogauer M, Navajas D, Taback NA, Millet EJ, Fredberg JJ. Time scale and other invariants of integrative mechanical behavior in living cells. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:041914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.041914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell HW, Sparrow MP. Increased responsiveness to cholinergic stimulation of small compared to large diameter cartilaginous bronchi. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:298–305. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07020298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sparrow MP, Willet KE, Mitchell HW. Airway diameter determines flow-resistance and sensitivity to contractile mediators in perfused bronchial segments. Agents Actions Suppl. 1990;31:63–66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7379-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin C, Uhlig S, Ullrich V. Videomicroscopy of methacholine-induced contraction of individual airways in precision-cut lung slices. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2479–2487. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen C, Kudo M, Rutaganira F, Takano H, Lee C, Atakilit A, Robinett KS, Uede T, Wolters PJ, Shokat KM, et al. Integrin α9β1 in airway smooth muscle suppresses exaggerated airway narrowing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2916–2927. doi: 10.1172/JCI60387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kudo M, Melton AC, Chen C, Engler MB, Huang KE, Ren X, Wang Y, Bernstein X, Li JT, Atabai K, et al. IL-17A produced by αβ T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat Med. 2012;18:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]