Abstract

Context

Adverse perinatal circumstances have been associated with increased risk of autism. Women exposed to childhood abuse experience more adverse perinatal circumstances than women unexposed, but whether abuse is associated with autism in offspring is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether maternal exposure to childhood abuse is associated with risk of autism, and whether possible increased risk is accounted for by higher prevalence of adverse perinatal circumstances among abused women, including gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use, intimate partner abuse, prior abortion, pregnancy less than 37 weeks, low birth weight, alcohol use, and smoking during pregnancy.

Design and Setting

Nurses’ Health Study II, a population-based longitudinal cohort of 116,430 women.

Patients or Other Participants

Participants with data on childhood abuse and child’s autism status (97% White). Controls were randomly selected from among children of women who did not report autism in offspring (N mothers of children with autism = 451; N mothers of children without autism=52,498).

Main Outcome Measure

Autism spectrum disorder, assessed by maternal report, validated with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised in a subsample.

Results

Exposure to abuse was associated with increased risk of autism in children in a monotonically increasing fashion. The highest level of abuse was associated with the greatest prevalence of autism (1.8% versus 0.7% in women not abused, P = 0.005) and the greatest risk for autism adjusted for demographic factors (risk ratio=3.7, 95% confidence interval=2.3, 5.8). All adverse perinatal circumstances were more prevalent in women abused except low birth weight. Adjusted for perinatal factors, the association of maternal abuse with autism was slightly attenuated (highest level of abuse, risk ratio = 3.0, 95% confidence interval=1.9, 4.9).

Conclusions

We identify an intergenerational association between childhood exposure to abuse and risk for autism in the subsequent generation. Adverse perinatal circumstances accounted for only a small portion of this increased risk.

Keywords: Autism, childhood abuse, birth weight, smoking, intimate partner abuse, prenatal factors

Introduction

Although the etiology of autism is mostly unknown, many hypotheses focus on the perinatal period as potentially critical for the development of autism. Prematurity1, low birth weight1,2, gestational diabetes, hypertension3, prolonged1 or very short labor4, maternal uterine bleeding5, being small for gestational age6, and gestation less than 35 weeks7 have been associated with elevated risk of autism. Additionally, maternal smoking,6 use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,8 and exposure to intimate partner violence in the prenatal period9 have been associated with higher risk of having a child with autism. Before and during pregnancy, women exposed to childhood abuse are more likely than those unexposed to experience circumstances and engage in behaviors that may be detrimental to the fetus, including smoking10,11, drug use11–14, overweight15,16, stress11,17 and intimate partner violence victimization18–20. Experience of childhood abuse is also associated with unintended pregnancy21, preterm labor22 and low birth weight11. Thus, maternal exposure to childhood abuse may be a risk factor for autism. Yet, to our knowledge, the association between maternal exposure to childhood abuse and risk of autism has not been examined.

In this paper we assess the relationship between maternal exposure to childhood abuse and risk of autism in a large population-based cohort. We further examine several perinatal exposures as possible mediators of the potentially elevated risk of autism in children of women exposed to childhood abuse.

Methods

Sample

We use data from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), a cohort of 116,430 female nurses originally recruited in 1989 from 14 populous U.S. states and followed up with biennial questionnaires. We examine data from women who reported whether they had ever had a child with autism spectrum disorder and who answered a supplemental 2001 questionnaire about childhood abuse (n=54,963 women). The Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board approved this research. Completion and return of questionnaires sent by U.S. mail constitutes implied consent.

Measures

Selection of cases and controls

In the 2005 biennial questionnaire, we asked respondents if they had a child diagnosed with autism, Asperger’s syndrome, or other autism spectrum disorder. In 2007–2008 we sent a follow-up questionnaire to 756 women currently participating in NHS II who responded that they had a child with any of these diagnoses, querying the affected child’s sex, birth date, and diagnoses (response rate=84%, n=636).

Some cases were excluded based on responses to the follow-up questionnaire. If women reported any of the following overlapping circumstances, they were excluded: they did not have a child with autism (n=32); the affected child was adopted (n=9); they did not want to participate (n=20); or they did not report the child’s birth year (n=71). Women who reported the affected child had trisomy 18, Fragile X, an XXY genotype, or Down, Angelman, Jacobsen’s, or Rett’s syndrome were also excluded (n=11). Here we refer to ‘cases’ as children meeting these inclusion criteria; we use ‘autism’ to refer to autism spectrum disorder. Of the remaining 549 cases, 98 women did not participate in the questionnaire assessing childhood abuse, leaving 451 cases. Women who reported they had a child with autism in the 2005 questionnaire but were not included in the analyses (N=389) were similar to women who reported a child with autism and were included in analyses (N=451) on year of birth (median = 1957 for both groups), marital status (83.0% of women not included were married versus 85.8% of included women), and smoking status at NHSII enrollment in 1989 (10.3% of excluded women were smokers versus 11.0% of included women).

Autism diagnosis was validated in a subsample of cases by telephone interview of 50 randomly selected mothers who indicated willingness to complete the interview (81% of mothers were willing to be interviewed), using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)23,24. Women who agreed to participate in the validation substudy were similar in the ASD diagnoses reported in their child to women who were not willing to participate (women willing to participate: 25% reported autism, 51% Asperger’s, and 25% pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS); women not willing to participate: 25% reported autism, 49% Asperger’s, and 23% PDD-NOS). Women not willing to participate in the validation study also did not differ from those willing to participant on child’s year of birth, sex, low birth weight prevalence or prematurity status.

In this substudy, 43 children (86%, 95% confidence interval=74%, 93%) met ADI-R criteria for an autism diagnosis, defined by meeting cutoff scores in all 3 domains and having onset by age 3 years; the remaining individuals met the onset criterion and communication domain cutoff, and either missed full diagnosis by one point in one domain (n=5) or met cutoffs in one or two domains only (n=2). The ADI-R provides an algorithm for full autistic disorder but not autism spectrum disorder. It is important to note that all children in the validation study demonstrated autistic behaviors. Children who did not meet full ADI-R criteria narrowly missed, thus may be on the autism spectrum.

Controls were parous women who reported never having a child with autism and who responded to the 2001 questionnaire reporting year and sex of each birth and childhood abuse. To assure independence of maternal characteristics among controls, we randomly selected one birth per woman with data on childhood abuse from among her live births (n= 52,498). At baseline in 1989, women included in our analyses were more likely to have ever been pregnant (91% versus 68%), less likely to smoke (29% versus 36%), and more likely to be White (97% versus 94%) compared with women not included.

Maternal exposure to childhood abuse

Abuse experiences were assessed in 2001. Combined childhood physical and emotional abuse before age 12 years was assessed with 5 questions from the Physical and Emotional Abuse Subscale of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire25 querying the frequency of people in the family: 1) hitting so hard it left bruises, 2) punishing in a way that seemed cruel, 3) insulting, 4) screaming and yelling, and 5) punishing with a belt or other hard object. For each item, response options included never, rarely, sometimes, often, or very often true. Responses were assigned values from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) and were summed following questionnaire scoring recommendations. In a validation study, the scale had good internal consistency (Chronbach’s α=0.94) and test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.82) over a 2- to 6-month interval25. The resulting scale was divided approximately into quartiles to calculate risk ratios and to investigate a possible dose-response relationship between severity of child abuse and risk of autism.

Sexual abuse occurring in two time periods was assessed, before age 12 years and age 12 to 17 years. For each time period, two questions queried unwanted sexual touching by an adult or older child and forced or coerced sexual contact by an adult or older child26. Response options included never, once, or more than once. To create a single measure, we assigned one point for each “once” answer and two points for each “more than once” answer. We then grouped these points for analysis as follows: 0 points was considered no abuse, 1 or 2 points was considered “mild” abuse, 3 or 4 points was considered “moderate” abuse, and 5 or more points was considered “severe” sexual abuse.

As exposure to high levels of both sexual and physical and emotional abuse could be associated with greater risk of autism in offspring than exposure to either type alone, we also created a measure of combined physical, emotional and sexual abuse by summing the physical/emotional and sexual abuse measures.

Potential mediators

In 2001, birth weight, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, and lifetime exposure to intimate-partner emotional, physical and sexual abuse was assessed. Birth weight was by maternal report in five categories: below 5, 5 to 5.4, 5.5 to 6.9, 7.0 to 8.4, 8.5 to 9, and above 9 pounds. Smoking during pregnancy was assessed with a single question: “how many cigarettes did you smoke per day during this pregnancy?” Responses were dichotomized as any/none. Alcohol use during pregnancy was assessed with the question: “on average, how much alcohol did you drink per week during this pregnancy?” As very few women had more than 1 drink/week, response options were coded as none, 1, or 2 or more drinks/week.27 Lifetime history of intimate partner abuse was assessed in 2001 with a modified version of the Assessing Abuse Scale28. Fear of partner and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were each assessed with one question: “Have you ever been made to feel afraid of your spouse/significant other?” (fear of partner); “Have you ever been emotionally abused by your spouse/significant other?” (emotional abuse); “Have you ever been hit, slapped, kicked or otherwise physically hurt by your spouse/significant other?” (physical abuse); “Has your spouse/significant other ever forced you into sexual activities?” (sexual abuse). Following these questions, respondents indicated the calendar years in which any of the types of abuse occurred. We included abuse in the year before the birth year as a potential mediator as abuse in the calendar year before the birth year has been associated with risk of autism.9 Having had an abortion prior to the birth of the index child was coded dichotomously based on lifetime history of abortions, including ages at occurrences, assessed in 1993 and updated in 1997, 1999, and 2001. Gestational diabetes was coded dichotomously from questions regarding history of gestational diabetes and year of diagnosis, assessed retrospectively in 1989 and updated biennially. Lifetime history and age at occurrences of toxemia/preeclampsia during pregnancy, defined for the respondent as “raised blood pressure and proteinuria” was assessed in 1989 and updated biennially.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use was assessed biennially from 1996 to 20078,29. Women were asked whether in the past two years they had regularly used Paxil, Prozac, or Zoloft. Women using any of these were coded as having used a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) in the perinatal period for births occurring in the two years queried by the questionnaire. As the first SSRI (Prozac) was available in the US in 198830, all women who gave birth prior to 1988 were coded as not having used an SSRI during pregnancy. Additionally, women were asked in 1993 whether they had ever used Prozac or Zoloft. Women who reported never having used these were coded as not having used SSRIs during births in 1993 or earlier. Women who reported that they had ever used an SSRI and whose child was born between 1989 to 1993 were excluded from analyses using this variable. Although these women had used an SSRI sometime during the 4-year time period queried, it is unknown whether they used an SSRI during the pregnancy that occurred during these years. Maternal age at child’s birth was coded as: less than 25, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, and 40 years or older. Year of child’s birth was continuous, and maternal childhood socioeconomic status was measured by the maximum of her parents’ education in her infancy.

Analyses

We first ascertained whether maternal physical/emotional, sexual, and combined abuse were associated with risk of autism in children using χ2 tests. We next examined the prevalence of perinatal risk factors by maternal childhood abuse status. To determine whether maternal childhood abuse was associated with risk of autism in children after adjusting for potential confounders, we modeled autism risk with either maternal childhood physical/emotional abuse, sexual abuse, or combined sexual, physical, and emotional abuse adjusted for maternal childhood socioeconomic status, maternal age at birth, birth year, and child’s sex.

To examine potential mediation by perinatal risk factors, we modeled autism risk as a function of combined maternal sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, perinatal risk factors and potential confounders. We assessed mediation proportion using the SAS Mediate macro31,32. Finally, we conducted models stratified by child’s sex to investigate possible sex-specific relationships between maternal childhood abuse and autism risk.

We used generalized estimating equations with a log link and Poisson distribution to estimate risk ratios33. To calculate statistical significance for the prevalence of gestational risk factors by combined childhood physical, emotional and sexual abuse, we modeled each risk factor as a dichotomous dependent variable with childhood abuse as the independent variable using generalized estimating equations with a log link and binomial distribution. To calculate statistical significance for the prevalence of alcohol use, which was measured in three levels, we used ordered logistic regression with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution.

Results

Approximately 3% of women (n = 1788, 3.4%) were exposed to serious sexual abuse. Prevalence of autism was elevated but not statistically significantly in children of women exposed to serious sexual abuse compared with children of women unexposed to sexual abuse (1.3% of children of women exposed were autistic versus 0.8% of children of women unexposed, P = 0.11). Women exposed to physical and emotional abuse were more likely to have a child with autism (highest quartile abuse, 1.1% of children were autistic; no abuse, 0.7% of children were autistic, P = 0.003). The highest level of mother’s combined sexual, physical, and emotional abuse was associated with the greatest prevalence of autism in children (1.8% of children versus 0.7% of children of women not abused, P = 0.005).

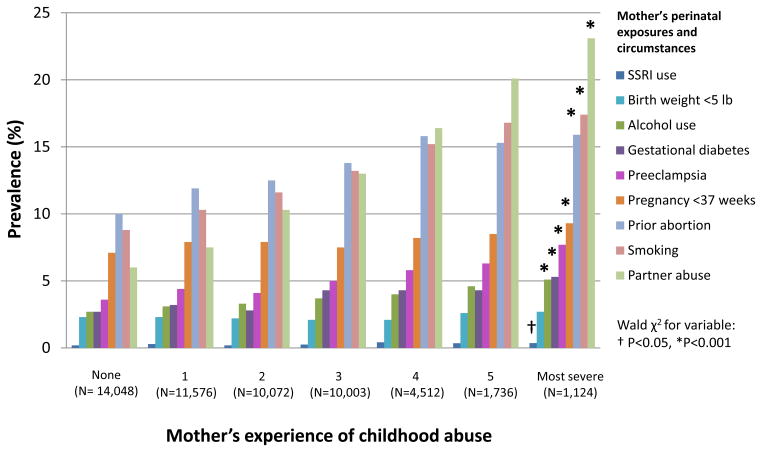

Mother’s combined childhood physical, emotional and sexual abuse was associated with increased prevalence of nearly all adverse circumstances in the perinatal period, in dose-response fashion (Figure). Women exposed to the highest level of abuse, compared with women not exposed to abuse, were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (17.4% versus 8.8%), drink alcohol (5.1% versus 2.8% had more than 1 drink/week), have gestational diabetes (5.3% versus 2.7%), preeclampsia (7.7% versus 3.6%), a prior abortion (15.9% versus 10.0%), gestation of less than 37 weeks (9.4% versus 7.1%), use selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the perinatal period (0.4%, versus 0.2%), and be victimized by intimate partner abuse in the year before the birth year (23.3% versus 6.1%). Women exposed to childhood abuse were not statistically significantly more likely to give birth to a child who weighed less than 5 pounds; however, they were more likely to have a child who did not weigh 7 to 8.5 lbs, the birth weight range that has been associated with lowest infant mortality34.

Figure.

Perinatal adverse circumstances by mother’s exposure to childhood physical, emotional and sexual abuse, Nurses’ Health Study II (n=52,949)

In models adjusted for demographic variables (but not perinatal risk factors), women exposed to either sexual or physical/emotional abuse were more likely to have a child with autism in a monotonically increasing fashion (Table 1, Models 1 and 2). Combined sexual, physical and emotional abuse was also associated with risk of autism in a monotonically increasing fashion (Table 2, Model 1). The 1,125 women exposed to the highest level of combined physical, emotional and sexual abuse in childhood were at greatest risk of having a child with autism compared with women unexposed to childhood abuse (risk ratio = 3.7, 95% confidence interval = 2.3, 5.8, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Mother’s exposure to childhood sexual or physical and emotional abuse and risk of autism in her child, Nurses’ Health Study II (N autism cases = 451, N controls = 52,498)†

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N | Risk ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

| Childhood sexual abuse | |||

| None | 35,175 | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| Mild | 12,595 | 1.2 (1.0. 1.5) | |

| Moderate | 3,391 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | |

| Severe | 1,788 | 2.0 (1.3, 3.1)** | |

| Childhood physical and emotional abuse | |||

| None | 18,342 | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| 2nd quartile | 11,516 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | |

| 3rd quartile | 10,545 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | |

| Top quartile | 12,546 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1)*** | |

Models are adjusted for mother’s age at birth, year of birth of the child, mother’s socioeconomic status in childhood, and sex of child.

Wald χ2 significant: ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

Table 2.

Mother’s exposure to combined sexual, physical, and emotional childhood abuse and risk of autism in her child, with and without perinatal risk factors, Nurses’ Health Study II, (N autism cases = 447; N controls = 52,478)†

| Model 1: Unadjusted for perinatal factors | Model 2: Adjusted for perinatal factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N | Risk ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||

| Childhood physical, emotional, and sexual abuse | |||

| 0: None | 14,008 | 1.0 [Reference] | 1.0 [Reference] |

| 1 | 11,551 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| 2 | 10,045 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) |

| 3 | 9,969 | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) |

| 4 | 4,497 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.3) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) |

| 5 | 1,731 | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.4) |

| 6: Most severe | 1,124 | 3.7 (2.3, 5.8)*** | 3.0 (1.9, 4.8)*** |

| Birth weight (pounds) | |||

| Less than 5 | 2.2 (1.2, 3.7) | ||

| 5 to 5.4 | 1.3 (0.6, 2.9) | ||

| 5.5 to 6.9 | 1.2 (1.0, 1.6) | ||

| 7 to 8.4 | 1.0 [Reference] | ||

| 8.5 to 9.9 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | ||

| 10 or more | 1.3 (0.8, 2.2) | ||

| Gestational diabetes | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5)*** | ||

| Smoking during pregnancy | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | ||

| Abortion prior to birth | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | ||

| Alcohol during pregnancy | |||

| None | 45,745 | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| 1 drink/week | 5,142 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | |

| 2 or more drinks/week | 1,745 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | |

| Preeclampsia | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | ||

| Intimate partner abuse | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8)* | ||

| Pregnancy length (weeks) | |||

| Less than 37 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | ||

| 37 to 42 | 1.0 [Reference] | ||

| 43 or more | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | ||

Models are adjusted for mother’s age at birth, year of birth of the child, mother’s socioeconomic status in childhood, and sex of child.

Wald χ2 for variable as a whole significant at: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

In the model including perinatal risk factors, childhood abuse remained highly significantly associated with increased risk for autism, although risk ratio estimates were slightly attenuated (Table 2, Model 2). The perinatal factors we examined statistically accounted for 7% of the association between child abuse and autism risk, although this estimate did not statistically differ from zero. Models stratified by sex showed similarly elevated risk of autism in female and male children of women exposed to childhood abuse, and an abuse-by-sex interaction term was not statistically significant. As only 125 women were exposed to SSRIs in the perinatal period, models including SSRI use would not converge. We therefore excluded SSRI use as a potential mediator.

We conducted further analyses to identify which of the perinatal factors were most important in mediating the association between childhood abuse and risk of autism in offspring. We calculated mediation for each perinatal factor separately, adjusted for maternal childhood SES and age at birth, and the birth year and sex of the child. In these analyses, we found gestational diabetes (mediation=3.5%) and abortion prior to the birth (mediation=3%) to be the strongest mediators of the child abuse/autism relationship. Smoking during pregnancy mediated 2% of the association, and the remaining variables mediated 1% or less.

As childhood abuse was strongly associated with most of the perinatal factors examined, we conducted additional analyses to investigate whether child abuse might explain the statistical relationship between the perinatal factors and autism, in other words, whether childhood abuse might confound the association between these factors and autism. We examined the association of autism with each perinatal factor in separate models, adjusted for demographic factors, with and without childhood abuse as an additional independent variable.

In these analyses, the associations between autism and prior abortion, smoking, and intimate partner violence were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for childhood abuse (attenuation range, 12 to 19%). The association of gestational diabetes and autism was very slightly attenuated. The associations of pregnancy <37 weeks and low birth weight with autism were not attenuated after adjusting for childhood abuse. Preeclampsia and alcohol use were not associated with autism.

Discussion

We found maternal exposure to abuse in childhood was associated with elevated risk of autism in a monotonically increasing fashion. Notably, women exposed to the highest level of physical/emotional abuse, comprising one-quarter of the women in our study, were at 60% elevated risk of having a child with autism compared with women not exposed to abuse. Additionally, we found that an array of perinatal factors were associated with both child abuse history and autism risk. However, these factors accounted for only a small part of the relationship between maternal abuse history and autism. No prior studies have examined early-life maternal exposures to stressors as possible risk factors for autism, however, several maternal stressors in the prenatal period have been associated with risk of autism, such as stressful life events9,35,36, though findings are mixed37.

Our results are consistent with at least four possibilities. First, additional unmeasured perinatal adverse circumstances associated with childhood abuse, such as infection38–40, poor diet41, insufficient prenatal care2, medication use8, illegal drug use11, and stressful life events17,42,43, may account for all of the association we found.

Second, the experience of childhood abuse and its behavioral, psychological and physical sequelae may cause alterations to the mother’s biological systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, and the immune system, which may in turn directly increase risk of autism in children. Childhood abuse has been associated with dysregulated HPA axes in both women44–46 and their infants47. Dysregulation of the HPA axis has been observed in persons with autism48, and it has been hypothesized that dysregulation of the maternal HPA axis affects the fetal brain49,50. Additionally, exposure to acute psychosocial stressors may increase secretion of androgen51,52, and some evidence suggests that exposure to high prenatal concentrations of androgen is associated with autistic traits.53,54 However, whether childhood abuse leads to persistently elevated maternal androgens is unknown. Immune dysfunction has also been associated with exposure to childhood abuse55–60. Immune dysfunction and inflammation, including neuroinflammation, are more prevalent in persons with autism61–66. Maternal inflammation affects the developing brain and maternal inflammation and immune function67–69 have been hypothesized to be causes of autism70–74.

Third, mother’s exposure to childhood abuse may, through epigenetic75,76 or other mechanisms, increase her biological reactivity to physical and psychological stressors through sensitization of the central nervous system45, dysregulation of the HPA axis77, and effects on the prefrontal cortex that impact the threat-appraisal response system78. Hyperreactivity to stressors may in turn negatively affect the developing fetus through effects on the mother and fetus’ HPA and HPG axes and immune system function79.

Fourth, mother’s exposure to abuse in childhood may be an indicator of genetic risk for autism, as mental illness in parents is associated with child abuse perpetration80–82, and several studies have suggested that genetic risk for autism may overlap with genetic risk for other mental disorders7,83–86. Thus, perpetration of child abuse by the grandparents and experience of abuse in childhood by the mother may be indicators of genetic risk for autism in the child.

Our study identifies an intergenerational association between a woman’s childhood exposure to violence and risk for a severe developmental disorder in her children. Given the numerous sequelae of the adverse perinatal circumstances we examined87–92, it is likely that children of women exposed to childhood abuse suffer from higher prevalence of a constellation of additional health problems compared with children of women who were not abused. Prior studies of the association between childhood abuse and perinatal risk factors have generally been conducted in small samples with a limited range of outcomes examined.93,94 Thus, the present study is the most comprehensive examination to date of the relationship between maternal childhood abuse and perinatal risk factors in a large population-based sample.

Our results should be considered in light of two important limitations. First, child’s autism, participant’s childhood abuse and participants’ gestational exposures were by participant report. Report of autism was validated by the ADI-R, an instrument with good reliability and validity24,95. While this approach is consistent with a large body of epidemiologic research, it does not constitute a diagnosis. Self-report of health-related circumstances in this cohort of professional nurses has been highly accurate in multiple validation studies.96–98 Nonetheless, misreporting of autism, childhood abuse exposure, or gestational exposures may have biased our results. Second, women reported their exposure to childhood abuse after knowing that they had a child with autism. If knowledge of their child’s autism status affected their report of experience of childhood abuse, this may have biased our results. However, women’s experience of childhood abuse was not queried in the context of her children’s autism status. Childhood abuse and autism were assessed in separate questionnaires four years apart, thus reducing likelihood of bias.

If the association we identify here between maternal childhood abuse and autism is due in part to direct or indirect effects of abuse (as opposed to shared genetic risk for abuse exposure and autism), this has several implications for clinical practice. First, we provide another compelling reason to increase efforts to prevent childhood abuse. Second, we identify a population at elevated risk of having a child with autism, women with a history of moderate or serious childhood abuse. Third, given the suggestion of mediation of autism risk through adverse perinatal circumstances, we suggest a possible means of reducing autism risk in children of these women, namely, though prevention of adverse perinatal circumstances.

In terms of research, studies examining perinatal risk factors for autism should consider potential confounding by maternal childhood abuse. Maternal abuse was strongly associated with nearly every perinatal risk factor we examined, and adjustment for abuse attenuated the associations of several perinatal risk factors with autism. If maternal abuse increases risk of autism through mechanisms not mediated by perinatal risk factors, or if maternal abuse is an indicator of genetic risk for autism, studies examining perinatal risk factors may find statistical associations with autism even if the factors play no causal role in autism etiology. If childhood abuse is associated with autism primarily through shared genetics, mental disorders that specifically increase risk for child abuse perpetration may overlap genetically with those that increase risk for autism. Future work should further investigate causal mechanisms by which maternal child abuse may be associated with autism.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Roberts and Weisskopf conceived the study. Dr. Roberts wrote the first draft of the manuscript, conducted the data analyses, had full access to all the data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Weisskopf, Lyall, Ascherio, and Rich-Edwards collected the data, edited drafts for important intellectual content, and approved the manuscript for submission. This study was funded by DOD W81XWH-08-1-0499, USAMRMC A-14917 and NIH 5-T32MH073124-08. The Nurses’ Health Study II is funded in part by NIH CA50385.

Abbreviations

- RR

Risk ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ADI-R

Autism Diagnostic Interview- Revised

- PDD-NOS

pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified

- HPA axis

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- HPG axis

hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest. We have not submitted these or similar results elsewhere.

The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brimacombe M, Ming X, Lamendola M. Prenatal and birth complications in autism. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burd L, Severud R, Kerbeshian J, Klug MG. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism. J Perinat Med. 1999;27:441–450. doi: 10.1515/JPM.1999.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krakowiak P, Walker CK, Bremer AA, Baker AS, Ozonoff S, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2012 doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasson EJ, Bower C, Petterson B, de Klerk N, Chaney G, Hallmayer JF. Perinatal Factors and the Development of Autism: A Population Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:618–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juul-Dam N, Townsend J, Courchesne E. Prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors in autism, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified, and the general population. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E63. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hultman CM, Sparen P, Cnattingius S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology. 2002;13:417–423. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, Vestergaard M, Olesen AV, Agerbo E, Schendel D, Thorsen P, Mortensen PB. Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:916–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi123. discussion 926-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, Odouli R, Hendrick V. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and childhood autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts AL, Lyall K, Rich-Edwards JW, Ascherio A, Weisskopf MG. Maternal exposure to intimate partner abuse prior to birth is associated with risk of autism in offspring. doi: 10.1177/1362361314566049. (Under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 (Suppl 2):S125–140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney ER. Childhood victimization: Relationship to adolescent pregnancy outcome. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:569–575. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:444 e441–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lester BM, Tronick EZ, LaGasse L, Seifer R, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Wright LL, Smeriglio VL, Lu J, Finnegan LP, Maza PL. The Maternal Lifestyle Study: Effects of Substance Exposure During Pregnancy on Neurodevelopmental Outcome in 1-Month-Old Infants. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1182–1192. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Lividoti Hibert EN, Jun HJ, Todd TJ, Kawachi I, Wright RJ. Abuse in childhood and adolescence as a predictor of type 2 diabetes in adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulder EJH, Robles de Medina PG, Huizink AC, Van den Bergh BRH, Buitelaar JK, Visser GHA. Prenatal maternal stress: effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Human Development. 2002;70:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charil A, Laplante DP, Vaillancourt C, King S. Prenatal stress and brain development. Brain Res Rev. 2010;65:56–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coker AL, Sanderson M, Dong B. Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2004;18:260–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: Maternal complications and birth outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;93:661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, Williamson DF, McMahon PM, Santelli JS, Nordenberg DF, Felitti VJ, Kendrick JS. Unintended pregnancy among adult women exposed to abuse or household dysfunction during their childhood. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horan DL, Hill LD, Schulkin J. Childhood sexual abuse and preterm labor in adulthood: an endocrinological hypothesis. Women’s Health Issues. 2000;10:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(99)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward-King J, Cohen IL, Penning H, Holden JJ. Brief report: telephone administration of the autism diagnostic interview--revised: reliability and suitability for use in research. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2010;40:1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0987-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore D, Gallup G, Schussel R. Disciplining Children in America: A Gallup Poll Report. The Gallup Organization; Princeton, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valenzuela CF, Morton RA, Diaz MR, Topper L. Does moderate drinking harm the fetal brain? Insights from animal models. Trends in Neurosciences. 2012;35:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Severity and frequency of injuries and associated entry into prenatal care. JAMA. 1992;267:3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadjikhani N. Serotonin, pregnancy and increased autism prevalence: is there a link? Med Hypotheses. 2010;74:880–883. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shorter E. Before Prozac: The troubled history of mood disorders in psychiatry. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertzmark E, Fauntleroy J, Skinner S, Jacobson D, Spiegelman D. The SAS mediate macro. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Channing Laboratory; Boston: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin DY, Fleming TR, De Gruttola V. Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Stat Med. 1997;16:1515–1527. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970715)16:13<1515::aid-sim572>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox AJ, Russell IT. Birthweight and perinatal mortality: II. On weight-specific mortality. International journal of epidemiology. 1983;12:319–325. doi: 10.1093/ije/12.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronald A, Pennell CE, Whitehouse AJO. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;1 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beversdorf DQ, Manning SE, Hillier A, Anderson SL, Nordgren RE, Walters SE, Nagaraja HN, Cooley WC, Gaelic SE, Bauman ML. Timing of prenatal stressors and autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-5037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Christensen J, Precht DH, Lu M, Olsen J. A nationwide study on the risk of autism after prenatal stress exposure to maternal bereavement. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1102–1107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atladóttir H, Thorsen P, Østergaard L, Schendel D, Lemcke S, Abdallah M, Parner E. Maternal Infection Requiring Hospitalization During Pregnancy and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fatemi SH, Earle J, Kanodia R, Kist D, Emamian ES, Patterson PH, Shi L, Sidwell R. Prenatal viral infection leads to pyramidal cell atrophy and macrocephaly in adulthood: implications for genesis of autism and schizophrenia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:25–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1015337611258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez J, Pavao J, Baumrind N, Kimerling R. The Relationship Between Child Abuse and Adult Obesity Among California Women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts AL, McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC. Adulthood stressors, history of childhood adversity, and risk of perpetration of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, Pedersen MG, Webb RT, Baker PN, Kenny LC, Mortensen PB. Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Archives of general psychiatry. 2008;65:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heim C, Newport DJ, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:575–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brand SR, Brennan PA, Newport DJ, Smith AK, Weiss T, Stowe ZN. The impact of maternal childhood abuse on maternal and infant HPA axis function in the postpartum period. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marinović-Ćurin J, Marinović-Terzić I, Bujas-Petković Z, Zekan L, Škrabić V, Đogaš Z, Terzić J. Slower cortisol response during ACTH stimulation test in autistic children. Eur Child Adolesc Psych. 2008;17:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD, Chicz-DeMet A, Dunkel-Schetter C, Porto M. Maternal stress, HPA activity, and fetal/infant outcome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;814:266–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wadhwa PD, Dunkel-Schetter C, Chicz-DeMet A, Porto M, Sandman CA. Prenatal psychosocial factors and the neuroendocrine axis in human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:432–446. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lennartsson AK, Kushnir MM, Bergquist J, Billig H, Jonsdottir IH. Sex steroid levels temporarily increase in response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy men and women. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2012;84:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schoofs D, Wolf OT. Are salivary gonadal steroid concentrations influenced by acute psychosocial stress? A study using the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2011;80:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voracek M. Fetal androgens and autism. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2010;196:416. doi: 10.1192/bjp.196.5.416. author reply 416–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knickmeyer R, Baron-Cohen S, Fane BA, Wheelwright S, Mathews GA, Conway GS, Brook CGD, Hines M. Androgens and autistic traits: A study of individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, Poulton R, Caspi A. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:243–250. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flier JS, Underhill LH, Chrousos GP. The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis and Immune-Mediated Inflammation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:1351–1363. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slopen N, Lewis TT, Gruenewald TL, Mujahid MS, Ryff CD, Albert MA, Williams DR. Early life adversity and inflammation in African Americans and Whites in the Midlife in the United States Survey. Psychosomatic Medicine. 72:694–701. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e9c16f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slopen N, Kubzansky L, McLaughlin K, Koenen K. Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dietert RR, Dietert JM. Potential for early-life immune insult including developmental immunotoxicity in autism and autism spectrum disorders: Focus on critical windows of immune vulnerability. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part B-Critical Reviews. 2008;11:660–680. doi: 10.1080/10937400802370923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herbert MR. Contributions of the environment and environmentally vulnerable physiology to autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:103–110. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328336a01f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Annals of neurology. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jyonouchi H, Geng L, Ruby A, Zimmerman-Bier B. Dysregulated innate immune responses in young children with autism spectrum disorders: their relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms and dietary intervention. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;51:77–85. doi: 10.1159/000084164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jyonouchi H, Sun S, Le H. Proinflammatory and regulatory cytokine production associated with innate and adaptive immune responses in children with autism spectrum disorders and developmental regression. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2001;120:170–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmerman AW, Jyonouchi H, Comi AM, Connors SL, Milstien S, Varsou A, Heyes MP. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum markers of inflammation in autism. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;33:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martin LA, Ashwood P, Braunschweig D, Cabanlit M, Van de Water J, Amaral DG. Stereotypies and hyperactivity in rhesus monkeys exposed to IgG from mothers of children with autism. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008;22:806–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wills S, Cabanlit M, Bennett J, Ashwood P, Amaral DG, Van de Water J. Detection of autoantibodies to neural cells of the cerebellum in the plasma of subjects with autism spectrum disorders. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ashwood P, Van de Water J. Is autism an autoimmune disease? Autoimmunity Reviews. 2004;3:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Licinio J, Alvarado I, Wong ML. Autoimmunity in autism. Molecular psychiatry. 2002;7:329. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Onore C, Careaga M, Ashwood P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ashdown H, Dumont Y, Ng M, Poole S, Boksa P, Luheshi GN. The role of cytokines in mediating effects of prenatal infection on the fetus: implications for schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry. 2006;11:47–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boksa P. Effects of prenatal infection on brain development and behavior: a review of findings from animal models. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2010;24:881–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jonakait GM. The effects of maternal inflammation on neuronal development: possible mechanisms. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Champagne FA, Weaver IC, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Champagne FA, Weaver IC, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Natural variations in maternal care are associated with estrogen receptor alpha expression and estrogen sensitivity in the medial preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4720–4724. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Essex MJ, Klein MH, Cho E, Kalin NH. Maternal stress beginning in infancy may sensitize children to later stress exposure: effects on cortisol and behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:776–784. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loman MM, Gunnar MR. Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus Suppressive Effects of Stress on Immune Function: Implications for Immunoprotection and Immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16:300–317. doi: 10.1159/000216188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roberts AL, Glymour MM, Koenen KC. Does maltreatment in childhood affect sexual orientation in adulthood? Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0021-9. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ronan KR, Canoy DF, Burke KJ. Child maltreatment: Prevalence, risk, solutions, obstacles. Australian Psychologist. 2009;44:195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Ehrensaft MK, Crawford TN. Associations of parental personality disorders and axis I disorders with childrearing behavior. Psychiatry. 2006;69:336–350. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2006.69.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burbach JPH, van der Zwaag B. Contact in the genetics of autism and schizophrenia. Trends in Neurosciences. 2009;32:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM, Cnattingius S, Savitz DA, Feychting M, Sparen P. Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1357–1362. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hodge D, Hoffman C, Sweeney D. Increased Psychopathology in Parents of Children with Autism: Genetic Liability or Burden of Caregiving? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2011;23:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yirmiya N, Shaked M. Psychiatric disorders in parents of children with autism: a meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adams KM, Li H, Nelson RL, Ogburn PL, Jr, Danilenko-Dixon DR. Sequelae of unrecognized gestational diabetes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178:1321–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hollander MH, Paarlberg KM, Huisjes AJM. Gestational Diabetes: A Review of the Current Literature and Guidelines. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2007;62:125–136. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000253303.92229.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shea AK, Steiner M. Cigarette Smoking During Pregnancy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:267–278. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. The Lancet. 371:261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ross MG, Beall MH. Adult Sequelae of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Seminars in Perinatology. 2008;32:213–218. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anderson CM. Preeclampsia: Exposing Future Cardiovascular Risk in Mothers and Their Children. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leeners B, Richter-Appelt H, Imthurn B, Rath W. Influence of childhood sexual abuse on pregnancy, delivery, and the early postpartum period in adult women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leeners B, Neumaier-Wagner P, Quarg AF, Rath W. Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) experiences: an underestimated factor in perinatal care. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85:971–976. doi: 10.1080/00016340600626917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Bildt A, Sytema S, Ketelaars C, Kraijer D, Mulder E, Volkmar F, Minderaa R. Interrelationship between autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic (ADOS-G), autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R), and the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) classification in children and adolescents with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:129–137. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022604.22374.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tomeo CA, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, Berkey CS, Hunter DJ, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Buka SL. Reproducibility and Validity of Maternal Recall of Pregnancy-Related Events. Epidemiology. 1999;10:774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:570–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health. 1997;6:49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]