Abstract

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is characterized by the t(15;17)(q22;q21), but additional chromosomal abnormalities (ACA) and other rearrangements can contribute in the development of the whole leukemic phenotype. We hypothesized that some ACA not detected by conventional techniques may be informative of the onset of APL. We performed the high-resolution SNP array (SNP-A) 6.0 (Affymetrix) in 48 patients diagnosed with APL on matched diagnosis and remission sample. Forty-six abnormalities were found as an acquired event in 23 patients (48%): 22 duplications, 23 deletions and 1 Copy-Neutral Loss of Heterozygocity (CN-LOH), being a duplication of 8(q24) (23%) and a deletion of 7(q33-qter) (6%) the most frequent copy-number abnormalities (CNA). Four patients (8%) showed CNAs adjacent to the breakpoints of the translocation. We compared our results with other APL series and found that, except for dup(8q24) and del(7q33-qter), ACA were infrequent (≤3%) but most of them recurrent (70%). Interestingly, having CNA or FLT3 mutation were mutually exclusive events. Neither the number of CNA, nor any specific CNA was associated significantly with prognosis. This study has delineated recurrent abnormalities in addition to t(15;17) that may act as secondary events and could explain leukemogenesis in up to 40% of APL cases with no ACA by conventional cytogenetics.

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is characterized by the t(15;17)(q22;q21) and the corresponding fusion gene PML-RARA. Additional chromosomal abnormalities (ACA) have been traditionally analyzed by conventional cytogenetics and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). In the last decade, the single-nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A) has become a powerful tool to perform what has been called “molecular karyotyping”, because it increases the resolution of conventional cytogenetics and detects a wider spectrum of abnormalities than FISH and other targeted techniques. Moreover, SNP-A are able to uncover regions of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH), a known phenomenon that occurs in cancer and which is not detectable by conventional cytogenetics.[1]

Most reports studying ACA in APL with SNP-A have used low resolution arrays or have not systematically matched tumor and germline sample,[2], [3] which is the only certain way to rule out copy-number variations (CNV).[4] Our interest in the clinical impact of ACA in APL was addressed in previous studies,[5], [6] but these were performed with conventional cytogenetics and FISH. We hypothesize that there may be some ACA not detected by conventional techniques that could be detected by high resolution SNP-A karyotype.

In this report, we have performed SNP-A in a series of APL patients to learn the incidence of cryptic ACA, as well as to study any possible clinical or biologic association.

Methods

Ethics Statement

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of our hospital (CEIB; Comité Ético de Investigación Biomédica). According to the Spanish law, written informed consent was obtained from all patients to participate in this study.

Patients and samples

Patients consecutively diagnosed with APL between November 1998 and February 2011 in the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe with available tumor and germline DNA sample were selected for this study. DNA was provided by Biobank La Fe. Tumor DNA was obtained from bone marrow cells at diagnosis. Matched germline DNA was obtained from bone marrow or peripheral blood when qRT-PCR was negative for PML-RARA rearrangement. Conventional cytogenetics, FISH or RT-PCR for the detection of PML-RARA fusion were performed in every case, as well as tests for mutation detection of FLT3-ITD and D835 as previously described.[7] Patients were enrolled in three consecutive multicenter PETHEMA trials (LPA96, LPA99, and LPA2005).[8], [9] Clinical data as well as treatment outcome and follow-up were collected prospectively.

SNP-A

Samples (500ng) were genotyped with Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 6.0 according to manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix Santa Clara, C.A., U.S.A.). DNA copy number and paired LOH analysis were performed using the Genotyping Console and the Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) software (Affymetrix). Filters applied for the detection of segmental copy-number abnormalities (CNA) were ≥10 consecutive markers in a region of at least 10Kb, and for regions of CN-LOH, ≥50 markers in at least 100Kb. All abnormalities found in the remission sample were ruled out and assumed as non-somatic. In addition, every potential abnormality was checked in the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation). Size, position, and location of genes were identified with UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). The human reference sequence used for alignment was the GRCh37/hg19assembly.

SNP-A data from other APL series

We compared our results with other APL series, namely APL cases from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network with publicly available SNP-A data (n = 20), the series of Akagi et al. (n = 47) and the series of Nowak et al. (n = 93).[2], [3] Lesions found in the TCGA cohort are listed in Table S1 in Appendix S1. Lesions found in the series of Akagi et al. and Nowak et al. were listed in the corresponding report.[2], [3]

Conversion of hg18 to version hg19 was done in these cases using the “Batch Coordinate Conversion (liftOver)” Tool from the UCSC Genome Browser, with a minimum ratio of bases that remapped >0.95.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used to analyze differences in the distribution of categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze differences in mean ranks. Unadjusted time-to-event analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier estimate and for comparisons, log-rank tests. Last update on clinical data was performed on March 2012. Median follow-up of patients alive was 77 months (range 13–151 mo.).

To investigate any possible association of the SNP-A abnormalities with clinical and biological characteristics, patients were divided according to the presence or not of CNA, the number of CNA and any recurrent CNA with n>3, such as +8/8q and CNA adjacent to the translocation breakpoints. Regarding the other APL series, we had available data for overall survival (OS) analysis from TCGA (n = 20) and Nowak et al. cohort (n = 89), and for relapse-free survival (RFS) from Nowak et al. cohort (n = 72 patients who achieved complete remission).

All computations were performed using the statistical package SPSS, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided P value below .05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of CNA and CN-LOH by SNP-A analysis

A total of 48 patients were included in this study. Main clinical and genetic characterization of our cohort is summarized in Table 1. Conventional cytogenetic studies were successful in 40 patients (83%). Seven of these patients (18%) had ACA (Table 1). SNP-A analysis revealed 46 abnormalities in 23 patients (48%). These consisted of 23 heterozygous deletions, 22 duplications and 1 CN-LOH (Figure 1). Ten (21%), 7 (15%) and 5 (12%) patients had one, two, and three or more anomalies, respectively.

Table 1. Main characteristics of our series.

| Characteristics | Median (range) |

| Age | 43 (17–76) |

| Leukocyte count (×109/L) | 2.2 (0–59) |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 9.0 (4.2–15.2) |

| Platelet count (x109/L) | 24.5 (2–168) |

| Bone marrow blasts (%) | 90 (53–100) |

| n (%) | |

| Male gender | 26 (54) |

| Therapy-related APL | 3 (6) |

| Mophologic variant | |

| Classical | 35 (73) |

| Hypogranular | 13 (28) |

| Risk group (Sanz et al)2 | |

| Low | 9 (19) |

| Intermediate | 26 (54) |

| High | 13 (27) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| t(15;17)(q22;q21) | 28 (58) |

| t(15;17)(q22;q21) and additional chromosomal abnormalities | 7 (15) |

| Cryptic translocation* | 5 (10) |

| Non-evaluable* | 8 (17) |

| PML-RARA isoform type | |

| Bcr-1 | 28 (58) |

| Bcr- 2 | 2 (4) |

| Bcr- 3 | 18 (38) |

| FLT3 mutational status | |

| FLT3-ITD | 9 (19) |

| FLT3-D835 | 1 (2) |

| Treatment Protocol | |

| LPA-96 | 3 (6) |

| LPA-99 | 22 (46) |

| LPA-2005 | 23 (48) |

*PML-RARA was diagnosed by FISH or RT-PCR.

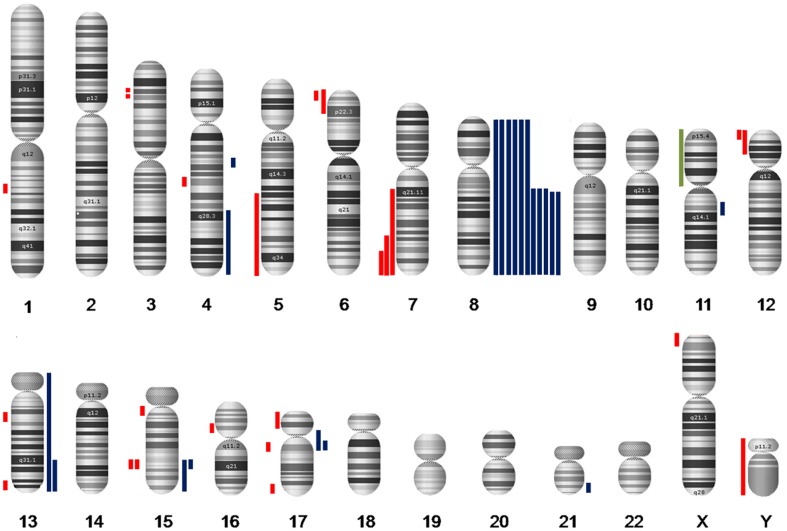

Figure 1. Karyogram of APL according to SNP-A analysis in our series.

Coloured bars depict the extension of abnormalities. Gains appear in blue at the right of each chromosome; losses in red and CN-LOH in green, at the left side of it.

A detailed list of the CNA and CN-LOH found in our series is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Median size of interstitial and telomeric CNA was 0.30 Mb (range, 0.11–19.38) and 77.48 Mb (range 3.45–146.36), respectively (Figure S1 in Appendix S1). No statistical difference in size was found for interstitial CNA (median size 0.46 Mb for duplications vs. 0.15 Mb for deletions).

Table 2. Detailed list of abnormalities found in our series (n = 48).

| APL_ID | Copy Number State | Chr | Cytoband | Start Position | End Position | Size (Mb) |

| Duplication of chr. 8 | ||||||

| 6 | 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 |

| 23 | 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 |

| 37 | 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 |

| 1 | 1 | 6 | p25.1–p24.3 | 4883499 | 7409514 | 2.53 |

| 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 | |

| 11 | 3 | 8 | q13.2-qter | 68579063 | 146364022 | 77.48 |

| 1 | X | p22.33 | 0 | 3454962 | 3.45 | |

| 26 | 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 |

| 3 | 11 | q13.4 | 72283371 | 72418939 | 0.14 | |

| 1 | 12 | p13.33 | 1027361 | 1134264 | 0.11 | |

| 33 | 1 | 7 | q21.11-qter | 82589142 | 159119708 | 76.53 |

| 3 | 4 | q27-qter | 123059206 | 191020138 | 67.96 | |

| 3 | 8 | q12.3-qter | 65285149 | 146364022 | 81.08 | |

| 40 | 1 | 7 | q31.32-qter | 121167520 | 159138663 | 37.97 |

| 3 | 8 | q12.3-qter | 65108706 | 146364022 | 81.26 | |

| 46 | 1 | 5 | q21.3-qter | 107659808 | 180915260 | 73.26 |

| 3 | 8 | q12.3-qter | 63759284 | 146364022 | 82.6 | |

| 47 | 1 | 7 | q33-qter | 137199691 | 159138663 | 21.94 |

| 3 | 8 | q13.2-qter | 68825854 | 146364022 | 77.54 | |

| CNA in t(15;17) breakpoints | ||||||

| 7 | 3 | 15 | q24.1 | 74168174 | 74304138 | 0.14 |

| 20 | 1 | 15 | q24.1 | 74691249 | 75117832 | 0.43 |

| 1 | 17 | q12 | 37959105 | 38079219 | 0.12 | |

| 3 | 21 | q22.13–q22.2 | 39661746 | 39772776 | 0.11 | |

| 32 | 1 | 17 | pter-p11.2 | 0 | 19050914 | 19.05 |

| 1 | Y | complete | 0 | 59373566 | 59.37 | |

| 3 | 15 | q24.1-qter | 74326556 | 102459244 | 28.13 | |

| 3 | 17 | p11.2–q21.2 | 19093472 | 38477259 | 19.38 | |

| 36 | 3 | 8 | complete | 0 | 146364022 | 146.36 |

| 3 | 13 | complete | 0 | 115169878 | 115.17 | |

| 3 | 15 | q24.1 | 74145053 | 74314995 | 0.17 | |

| 3 | 17 | q21.2 | 38505591 | 38673928 | 0.17 | |

| Others | ||||||

| 3 | 1 | 16 | p12.1 | 24507155 | 24661476 | 0.15 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | q24.2 | 167718498 | 168149489 | 0.43 |

| 10 | 1 | 4 | q24 | 105743315 | 105897864 | 0.15 |

| 13 | 1 | 12 | pter-p12.3 | 0 | 18489408 | 18.49 |

| 3 | 13 | q31.1-qter | 85060629 | 115169878 | 30.11 | |

| 21 | 1 | 17 | q25.3 | 76335284 | 76796083 | 0.46 |

| 22 | 3 | 4 | q21.3 | 87551324 | 87700668 | 149.34 |

| 25 | 1 | 6 | p25.1-p22.3 | 5544745 | 15635655 | 10.09 |

| 1 | 15 | q11.2-q12 | 23641501 | 27343875 | 3.7 | |

| 28 | CN-LOH | 11 | p15.5-p12 | 198509 | 42278838 | 42.08 |

| 29 | 1 | 3 | p24.2 | 24782029 | 28427029 | 3.65 |

| 1 | 3 | p22.3 | 34388000 | 35859690 | 1.47 | |

| 1 | 13 | q14.11 | 40282116 | 40786721 | 0.5 | |

| 1 | 13 | q33.2-q33.3 | 105672486 | 109302864 | 3.63 | |

| 1 | 13 | q33.3 | 109671057 | 109798831 | 0.13 | |

Recurrent SNP-A lesions

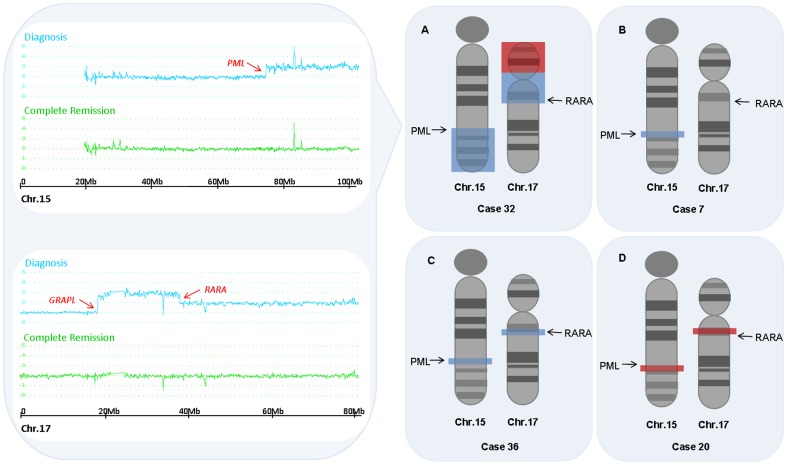

The most common abnormality was a duplication of +8/8q (11 patients, 23%), followed by a deletion of 7q (3 patients, 6%). Of note, 7 out of 11 +8/8q had not been detected by conventional cytogenetics. Four cases (8%) showed CNA adjacent to the breakpoints of the t(15;17) translocation (Figure 2). In case APL_20, two partial deletions were 0.5 Mb telomeric to PML and 0.5 Mb centromeric to RARA. In case APL_32, the SNP-A showed two large amplifications adjacent to the PML and the RARA gene and, additionally, a heterozygous partial deletion of 17p contiguous to the amplification. The breakpoint was in the coding region of GRAPL gene instead of the centromere. This event corresponds to an isochromosome of the derivative chromosome 17 of the translocation t(15;17) [ider(17)(q10)t(15;17)], which is occasionally seen in some APL cases by conventional cytogenetics. We could not confirm it in this case because no evaluable metaphases were obtained. In case APL_36, two small amplifications were found involving the PML and the RARA genes, and in case APL_7, a small amplification included part of the coding region of the PML gene. These 2 cases were among the 5 patients with cryptic translocation by conventional cytogenetics of our series.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of CNA adjacent to the translocation breakpoints found in our series.

On the left panel, the Smooth Signal of chromosome 15 and 17 from case APL_32 are represented. Results from diagnosis sample are shown in blue and from complete remission sample, in green. On the right, chromosomes 15 and 17 are depicted with G-banding and arrows pointing the location of the PML and RARA genes. Areas shaded in blue show regions duplicated and in red, deleted. Panel (A) corresponds to isochromosome der(17)t(15;17); Panel (B) shows a small duplication of the PML gene, and in panel (C) both the PML and the RARA genes are duplicated. These two cases had a cryptic t(15;17) by CC, that was revealed by FISH. In panel (D) two small deletions are found distally to the translocation breakpoints.

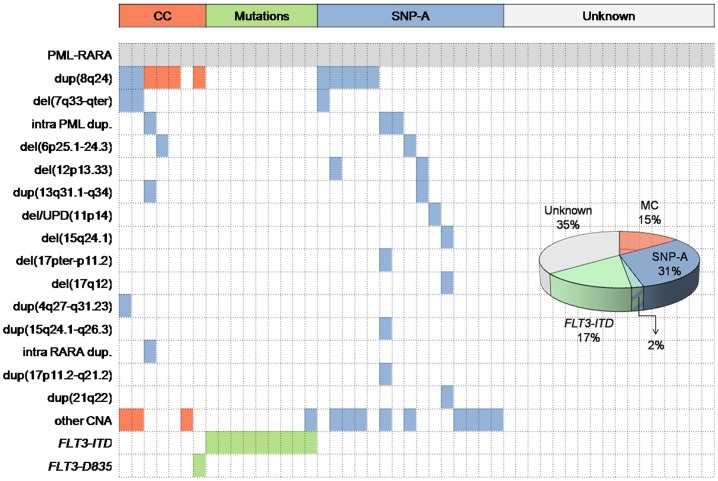

Except for the 3 patients that had del(7q) and +8/8q concomitantly, no other association with clinical or biologic variables was observed. Conventional cytogenetics and FLT3 mutation analysis revealed a secondary event to t(15;17) in 16 cases (33%). SNP-A uncovered cryptic additional abnormalities in 15 additional cases (31%). One third of cases still had no known secondary event (Figure 3). Patients carrying FLT3-ITD mutations had less frequently SNP-A anomalies (32% of mutations in patients without CNA vs. 4% in patients with at least one CNA; P = .016).

Figure 3. Heatmap and pie chart depicting abnormalities found in our series in addition to the t(15;17).

Each column represents one patient. Abnormalities are listed in the Y axis and coloured in the corresponding row of the heatmap. Abnormalities detected by Conventional Cytogenetics (CC) (red) and FLT3 mutations (green) are frequent events; however, SNP-A revealed an important proportion of patients with potentially leukemogeneic abnormalities (blue). Dup: duplication: del: deletion; CNA: copy-number abnormality.

Comparison with other series

The analysis of the type, size and number of lesions in each series is shown in Table 3. The series of Nowak et al. had fewer cases without CNA (17% in Nowak's series vs. 52%, 65% and 60% in our series, TCGA' and Akagi's series, respectively; P.001 in all three pairwise comparisons) and more abnormalities per case (median of 2 abnormalities in Nowak's series vs. 0 in all other report; P<.001 in all three pairwise comparisons). They also reported more deletions than duplications (65% of deletions in Nowak's series vs. 50% in this report and 29% in Akagi's series; P = .027 and .002, respectively) and a smaller size of each lesion (median size of 0.19 Mb vs. 18.77 Mb, 9.53 Mb and 45.11 Mb in this report, TCGA' and Akagi's series; P<.001, = .018 and <.001, respectively). Akagi et al. reported more CN-LOH (21% of CN-LOH vs. 2% and 3% in this report and Nowak's series; P = .009 and <.001, respectively).

Table 3. Comparison of type, size and number of SNP-A abnormalities in reported APL series.

| Akagi et al. | TCGA | Nowak et al. | This Report | |

| Number of patients | n = 47 | n = 20 | n = 93 | n = 48 |

| Array type | 50 k & 250 K | SNP 6.0 | SNP 6.0 | SNP 6.0 |

| Use of germline sample | 7 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | 48 (100%) |

| Patient's abnormalities | ||||

| No CNA | 28 (60%) | 13 (65%) | 16 (17%) | 25 (52%) |

| Trisomy 8/8q+ | 8 (17%) | 2 (10%) | 25 (27%) | 11 (23%) |

| Others | 11 (23%) | 5 (25%) | 52 (56%) | 12 (25%) |

| CNA types | ||||

| Duplications | 17 (50%) | 7 (54%) | 83 (32%) | 22 (48%) |

| Deletions | 10 (29%) | 6 (46%) | 171 (65%) | 23 (50%) |

| CN-LOH | 7 (21%) | 1 (5%)* | 7 (3%) | 1 (2%) |

| Total | 34 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 261 (100%) | 46 (100%) |

| CNA per case | ||||

| median | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| media | 0.72 | 0.75 | 2.78 | 0.96 |

| range | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–14 | 0–5 |

| Size (Mb) | ||||

| median | 45.11 | 9.53 | 0.19 | 18.77 |

| media | 55.06 | 25.65 | 16.38 | 41.72 |

| range | 0.02–146.36 | 0.13–146.36 | 0.001–191.15 | 0.11–146.36 |

*one Uniparental Tetrasomy has been included both in duplication and CN-LOH group.

CNA: Copy-Number Abnormality. CN-LOH: Copy-Neutral Loss of Heterozygocity.

The common deleted region (CDR) or the common gained region (CGR) of the CNA found in our series were delineated taking into account the boundaries reported by us and the other APL series (Table 4). Many CDR/CGR harbored well-known genes implicated in leukemia, such as MYC, NF1, TP53 or EZH2. In every series, CGR 8(q24) was, by far, the most frequent abnormality (ranging from 10% to 25%), followed by CDR 7(q33-qter) (ranging from 2% to 6%). The remaining CDR/CGR were present in a lower frequency (≤3% of patients). One third (n = 68 out of 208) of the whole cohort carried at least one of the recurrent CDR/CGR. Most of the abnormalities found in our series (70%; n = 32) were recurrent in the other series, and the remaining CNA were known abnormalities in myeloid neoplasms, such as 5q- and –Y.

Table 4. Minimal deleted or gained regions found in APL series, their frequency and the genes included in each region.

| Minimal deleted region (MDR) | Proximal | Distal | Size (Mb) | Akagi et al. (n = 47) | TCGA (n = 20) | Nowak et al. (n = 93) | This Report (n = 48) | Total n = 208 | Genes |

| del(6p25.1–24.3) | 5600438 | 7409514 | 1,81 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 3 (1%) | FARS2, NRN1, F13A1, LY86, RREB1, CAGE1. |

| del(6p24.1) | 12278913 | 13386241 | 1,11 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | EDN1, PHACTR1, TBC1D7, GF0D1. |

| del(7q33-qter) | 137199691 | 158861884 | 21,66 | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 10 (5%) | several genes including LUC7L2, EZH2. |

| del/UPD(11p14) | 22936456 | 30671304 | 7,73 | 3 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | LUZP2, ANO3, MUC15, SLC5A12, BBPX1, CCDC34, LGR4, LIN7C, BDNF, METTL15, KCNA4, FSHB, MPPED2. |

| del(12p13.33) | 1027361 | 1134264 | 0,11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 2 (1%) | RAD52, ERC1. |

| del(15q24.1) | 74691249 | 75117832 | 0,43 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | SEMA7A, UBL7, ARID3B, CLK3, EDC3, CYP1A1, CSK, LMAN1L. |

| del(17pter-p11.2) | 0 | 18935523 | 18,94 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | several genes including TP53. |

| del(17q12) | 37959105 | 38079219 | 0,12 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | IKZF3, GSDMB, ZPBP2, ORMDL3. |

| Minimal gained region (MGR) | |||||||||

| dup(4q27–q31.23) | 123059206 | 150420462 | 27,36 | 0 | 0 | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (3%) | several genes. |

| dup(8q24) | 122538604 | 132023578 | 9,48 | 8 (17%) | 2 (10%) | 23 (25%) | 11 (23%) | 44 (21%) | several genes including MYC. |

| dup(13q31.1–q34) | 85060629 | 115108397 | 30,05 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (2%) | several genes. |

| dup(15q24.1) intra PML | 74262253 | 74304138 | 0,04 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (3%) | PML. |

| dup(15q24.1–q26.3) | 74326556 | 102364660 | 28,04 | 2 (4%) | 0 | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (3%) | several genes including PML. |

| dup(17q21.2) intra RARA | 38505591 | 38673928 | 0,17 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | RARA. |

| dup(17p11.2–q21.2) | 21550542 | 38477259 | 16,93 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | several genes including NF1, RARA |

| dup(21q22) | 39661746 | 39772776 | 0,11 | 2 (4%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | KCNJ15, ERC. |

Two patterns of CNAs adjacent to the t(15;17) breakpoints were found recurrently. The first one was the pattern corresponding to ider(17)(q10)t(15;17) (5 cases, 2%). The breakpoint leading to deletion of 17p was found within the coding region of the GRAPL gene, the GRAP gene, or even more centromeric. The second recurrent pattern was the duplication of the PML locus without reciprocal duplication of the RARA locus, (5 cases, 2%).

We observed again that CGR 8(q24) and CDR 7(q33-qter) appeared concomitantly [80% of deletions in 7(q33-qter) in patients with dup(8q24) vs. 18% in patients without dup(8q24); P <.001].

Correlation with clinical data

No single CNA showed an association with clinical variables or a prognostic impact in terms of OS and RFS, as was also the case of those cases with cryptic CNA that were not observed by conventional cytogenetics, and those with 0, 1 or ≥2 CNAs revealed by SNP-A.

We analyzed next every recurrent CDR/CGR in the series with available survival data. All three series had independent similar OS and RFS. No recurrent CDR/CGR showed a prognostic value; however, patients who carried ≥1 recurrent CDR/CGR showed a shorter 3-year OS (86% vs. 75%; P = .05), and RFS (90% vs. 78% in patients having 0 vs. ≥1 recurrent lesion; P = .05) (Figure S2 in Appendix S1).

Discussion

This study shows that high-resolution SNP-A analysis reveals ACA in roughly half the patients with APL (48%). Most of them (90%) had not been properly detected by conventional cytogenetics. Systematic use of matched diagnosis and molecular remission sample in every single case has allowed us to ascertain the somatic nature of these lesions. Moreover, the majority of them were recurrent (70%) but of low frequency (≤3%), and accounted for a secondary event in up to 40% of APL cases with no ACA by conventional cytogenetics.

Our analysis showed a low burden of CNA in our series, which is in line with previous reports of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (AML),[10] and even lower than AML of any kind,[11] suggesting that few additional lesions are needed in this type of leukemias. These findings differ widely from the results reported by Nowak et al.,[3] where they found three times more lesions per case and with a much smaller size. It could be possible that these differences are due to the lack of systematic use of germline sample and assumption of some CNV as somatic when not reported in public CNV databases.

Among the SNP-A abnormalities, +8/8q was the most frequent in our series and the other reports.[2], [3] Trisomy 8 is known to be the most frequent chromosomal abnormality in APL [5] and very common in myeloid neoplasms. However, SNP-A analysis allowed for a three-fold detection of duplications in chromosome 8 in our series. Of note, the CGR had a size of 9.5Mb and comprised few genes, including MYC as the most probable candidate gene, which has been shown to be deregulated and amplified in several types of leukemias and lymphomas.[12], [13] The second most recurrent abnormality was del(7q), which appeared in association with dup(8q24), both common CNA in myeloid neoplasms. Regarding CN-LOH, most series of APL and other translocation-associated leukemias have reported a very low rate (<5%),[3], [10], [14] which is in line with our findings and suggest a very low frequency of this event in APL.

CNA in the boundaries of t(15;17) breakpoints were disclosed in some patients. This also occurs in other supposedly balanced translocations in an even higher frequency (around 25% of core binding factor AML and 10% in CML).[10], [14] Two patterns seemed to be recurrent: the first one corresponded to an isochromosome derivative of chromosome 17(t15;17). Isochromosome 17q [i(17q)] is not monocentric but a dicentric chromosome. It has a breakpoint cluster region located at 17p11.2, which is a genetically unstable region that contains multiple low-copy repeats and segmental duplications.[15] We located the breakpoint region at the GRAPL gene. Other authors have located the breakpoint at the GRAP gene [3] or more centromeric in a non-coding region,[2] but all of them are within this breakpoint cluster region. This region has shown susceptibility to rearrangement and explains the relative high frequency of i(17q) in hematologic and non-hematologic cancers, as well as deletions in this area in Smith-Magenis syndrome.[15], [16] The fact that the i(17q) harbours the t(15;17) indicates that the i(17q) occurs as a secondary event, that in addition will produce an extra RARA-PML transcript.[17]

Cases with duplication of the PML gene were recurrent, and also similar cases have been reported before.[18] It is interesting that some of these cases had a cryptic t(15;17) according to conventional cytogenetics. APL cases with cryptic t(15;17) may be due to small interstitial insertions of PML or RARA genes one beside the other [19] or even ectopic to the natural gene loci. [18], [20], [21] Small deletions very close to the translocated genes have been reported in 10-30% of patients with CBF-AML [t(8;21) and inv(16)] and CML [t(9;22)], usually involving the translocated genes.[10], [14] Less frequently (∼1%), some cases have been described in such leukemias with deletions located in more telomeric or centromeric regions from the translocated gene, [10], [14] resembling our case APL_20. The study of such cases with imbalanced translocations may help to elucidate the mechanisms that give rise to the t(15;17).

The parallel study of FLT3-ITD mutations and CNA by SNP-A showed a mutually exclusive association of these events. This is in agreement with previous studies [2] and supports the hypothesis that tyrosin kinase activation through FLT3-ITD mutations is a sufficient cooperating event to produce APL and therefore, other genomic aberrations such as CNAs are not needed. In our series, FLT3 mutations and conventional cytogenetics revealed an additional abnormality in one third of patients. Interestingly, SNP-A analysis uncovered one additional third of patients from this cohort that carried acquired CNA/CN-LOH in the leukemic blasts. Most of those abnormalities were infrequent (≤3% of patients) but recurrent, indicating a role of these lesions in the development of APL and therefore the capability of high-resolution SNP-A karyotype to reveal hidden leukemogenic events. The majority of these recurrent CNAs and also some non-recurrent are well-known abnormalities in myeloid neoplasms. This suggests that additional events which occur after the t(15;17) are not necessarily exclusive of APL, but common with acute myeloid leukemia and other hematologic neoplasms. Likewise, these facts highlight the wide degree of heterogeneity seen in the cooperating events that contribute to APL.

Still another third of patients had neither FLT3 mutations nor ACA. Probably, more advanced technologies such as next-generation sequencing will help to elucidate the abnormalities acquired in these cases.

No independent association with prognosis could be established for any recurrent CNA, although we are aware of the small size of our series for this type of analysis. Even the most frequent CNA, dup(8q24), that has been assigned a prognostic value in certain hematologic neoplasms,[22], [23] was not related to the patient's outcome, as was also the case in previous reports of APL.[3], [5] However, patients who lacked an available remission sample, such as those who died before achieving complete remission, were not included in this study. This last fact may constitute a selection bias.

Carrying one or more CDR/CGR showed a trend towards a worse prognosis, although our cohort was heterogeneous for survival analysis and besides, multivariate analysis could not be performed. More solid evidence will therefore be required to confirm this finding. However, it is true that similar results have been reported before in other hematologic neoplasms [24]-[26] revealing that the more lesions in the cell's genome, the more complexity and poorer prognosis the disease has.

In summary, these data demonstrate an acquired lesion in leukemic blasts in 40% of patients with no ACA by conventional cytogenetics. The low frequency and recurrence of these ACA indicate the broad spectrum of abnormalities that can occur after the t(15;17) and are required for the leukemic transformation. Whether this picture can be fully explained using more comprehensive technology remains to be seen.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information file. Table S1. Lesions found in the 20 APL cases of the TCGA cohort. Figure S1. Graphic representation of the size and type of Copy Number Abnormalities (CNA) in our series. Figure S2. Survival curves of the reported APL series according to the number of CDR/CGR.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ana Martín, Elena Bellmunt and Raquel Amigó from “Biobank La Fe” for their help in sample processing and supply. We also thank the TCGA Research Network for access to the SNP-A results and associated clinical data described in the text.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Grant “Rio Hortega” (CM10/00321, CM11/00343), the Health Research Program (PI12/01047), the program “Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer” (RD12/0036/0014) and the “Red Cooperativa de Biobancos Hospitalarios” (RD09/0076/00021) from “Instituto de Salud Carlos III”, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain, (www.isciii.es); the research grant 2013/0327 from the “Instituto Investigación Sanitaria Hospital La Fe”, (www.iislafe.es); and the Excellence Research Project (PROMETEO/2011/025) granted by Generalitat Valenciana, (www.cece.gva.es). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. O'Keefe C, McDevitt MA, Maciejewski JP (2010) Copy neutral loss of heterozygosity: a novel chromosomal lesion in myeloid malignancies. Blood 115: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akagi T, Shih LY, Kato M, Kawamata N, Yamamoto G, et al. (2009) Hidden abnormalities and novel classification of t(15;17) acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) based on genomic alterations. Blood 113: 1741–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nowak D, Klaumuenzer M, Hanfstein B, Mossner M, Nolte F, et al. (2012) SNP array analysis of acute promyelocytic leukemia may be of prognostic relevance and identifies a potential high risk group with recurrent deletions on chromosomal subband 1q31.3. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 51: 756–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heinrichs S, Li C, Look AT (2010) SNP array analysis in hematologic malignancies: avoiding false discoveries. Blood 115: 4157–4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cervera J, Montesinos P, Hernandez-Rivas JM, Calasanz MJ, Aventin A, et al. (2010) Additional chromosome abnormalities in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy. Haematologica 95: 424–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernandez JM, Martin G, Gutierrez NC, Cervera J, Ferro MT, et al. (2001) Additional cytogenetic changes do not influence the outcome of patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with an ATRA plus anthracyclin based protocol. A report of the Spanish group PETHEMA. Haematologica 86: 807–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barragan E, Montesinos P, Camos M, Gonzalez M, Calasanz MJ, et al. (2011) Prognostic value of FLT3 mutations in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy. Haematologica 96: 1470–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanz MA, Martín G, González M, León A, Rayón C, et al. (2004) Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: a multicenter study by the PETHEMA group. Blood 103: 1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanz MA, Montesinos P, Rayón C, Holowiecka A, de la Serna J, et al. (2010) Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia based on all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline with addition of cytarabine in consolidation therapy for high-risk patients: further improvements in treatment outcome. Blood 115: 5137–5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuhn MW, Radtke I, Bullinger L, Goorha S, Cheng J, et al. (2012) High-resolution genomic profiling of adult and pediatric core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia reveals new recurrent genomic alterations. Blood 119: e67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walter MJ, Payton JE, Ries RE, Shannon WD, Deshmukh H, et al. (2009) Acquired copy number alterations in adult acute myeloid leukemia genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 12950–12955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delgado MD, Albajar M, Gomez-Casares MT, Batlle A, Leon J (2013) MYC oncogene in myeloid neoplasias. Clin Transl Oncol 15: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slack GW, Gascoyne RD (2011) MYC and aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Adv Anat Pathol 18: 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huh J, Jung CW, Kim JW, Kim HJ, Kim SH, et al. (2011) Genome-wide high density single-nucleotide polymorphism array-based karyotyping improves detection of clonal aberrations including der(9) deletion, but does not predict treatment outcomes after imatinib therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 90: 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barbouti A, Stankiewicz P, Nusbaum C, Cuomo C, Cook A, et al. (2004) The breakpoint region of the most common isochromosome, i(17q), in human neoplasia is characterized by a complex genomic architecture with large, palindromic, low-copy repeats. Am J Hum Genet 74: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen KS, Manian P, Koeuth T, Potocki L, Zhao Q, et al. (1997) Homologous recombination of a flanking repeat gene cluster is a mechanism for a common contiguous gene deletion syndrome. Nat Genet 17: 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manola KN, Karakosta M, Sambani C, Terzoudi G, Pagoni M, et al. (2010) Isochromosome der(17)(q10)t(15;17) in acute promyelocytic leukemia resulting in an additional copy of the RARA-PML fusion gene: report of \ases and review of the literature. Acta Haematol 123: 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koshy J, Qian YW, Bhagwath G, Willis M, Kelley TW, et al. (2012) Microarray, gene sequencing, and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analyses of a cryptic PML-RARA translocation. Cancer Genet 205: 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldschmidt N, Yehuda-Gafni O, Abeliovich D, Slyusarevsky E, Rund D (2010) Interstitial insertion of RARalpha gene into PML gene in a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) lacking the classic t(15;17). Hematology 15: 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haraguchi K, Ohno N, Tokunaga M, Itoyama T, Gotoh M, et al. (2009) Masked t(15;17) APL with the insertion of PML-RARalpha fusion gene in 4q21. Leuk Res 33: 1552–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garcia-Casado Z, Cervera J, Valencia A, Pajuelo JC, Mena-Duran AV, et al. (2006) A t(17;20)(q21;q12) masking a variant t(15;17)(q22;q21) in a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 168: 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Such E, Cervera J, Costa D, Solé F, Vallespí T, et al. (2011) Cytogenetic risk stratification in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica 96: 375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, et al. (2012) Revised International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Blood 120: 2454–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parkin B, Erba H, Ouillette P, Roulston D, Purkayastha A, et al. (2010) Acquired genomic copy number aberrations and survival in adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 116: 4958–4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tiu RV, Gondek LP, O'Keefe CL, Huh J, Sekeres MA, et al. (2009) New lesions detected by single nucleotide polymorphism array-based chromosomal analysis have important clinical impact in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 27: 5219–5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schweighofer CD, Coombes KR, Majewski T, Barron LL, Lerner S, et al. (2013) Genomic Variation by Whole-Genome SNP Mapping Arrays Predicts Time-to-Event Outcome in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Comparison of CLL and HapMap Genotypes. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD 15: 196–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information file. Table S1. Lesions found in the 20 APL cases of the TCGA cohort. Figure S1. Graphic representation of the size and type of Copy Number Abnormalities (CNA) in our series. Figure S2. Survival curves of the reported APL series according to the number of CDR/CGR.

(DOC)