Abstract

Highly pathogenic Avian influenza (HPAI) is a notifiable viral disease caused by avian influenza type A viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family. Type A influenza genome consists of eight segments of negative-sense RNA. RNA segment 2 encodes three proteins, PB1, PB1-F2, and N40, which are translated from the same mRNA by ribosomal leaky scanning and reinitiation. Since these proteins are critical for viral replication and pathogenesis, targeting their expression can be one of the approaches to control and resist HPAI. MicroRNAs are short noncoding RNAs that regulate a variety of biological processes such as cell growth, tissue differentiation, apoptosis, and viral infection. In this study, a set of 300 miRNAs expressed in chicken lungs were screened against the HPAI virus (H5N1) segment 2 with different screening parameter like thermodynamic stability of heteroduplex, seed sequence complementarity, conserved target sequence, and target-site accessibility for identifying miRNAs that can potentially target the transcript of segment 2 of H5N1. Chicken miRNAs gga-mir-133c, gga-mir-1710, and gga-mir-146c* are predicted to target the expression of PB1, PB1-F2, and N40 proteins. This indicates that chicken has genetic potential to resist/tolerate H5N1 infection and these can be suitably exploited in designing strategies for control of avian influenza in chicken.

Keywords: chicken, miRNA, H5N1, PB1, PB1-F2, N40

Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is a notifiable viral disease caused by avian influenza type A viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family. It affects poultry in which mortality may reach up to 100%.1,2 This causes significant economic losses to the poultry industry and raises a great public health threat due to potential host jump from animals to humans.3 Despite stringent control measures in the form of mass culling of poultry in and around the site of outbreak, re-emergence of avian influenza in poultry is frequently observed. Vaccination is unable to provide sufficient protection against HPAI virus (H5N1) of subsequent outbreaks, due to the characteristic genetic shift and drift seen in this virus.3 In view of the fact that poultry lines are developed by several generations of selection and planned breeding to meet the production requirements, protecting such valuable line against avian influenza is the need of the hour. Several anti-influenza drugs are used in case of humans; however, therapy is not recommended in poultry due to threat to effectiveness of the same antivirals as therapeutics for human influenza.4 Development of influenza-resistant chicken lines is advocated as a possible measure to control avian influenza in poultry. Although transgenesis is reported in poultry, the expression of transgene may not be consistent over generations. Moreover, since chicken is a popular protein source to the human population, genetic modification of chicken would raise several issues pertaining to genetically modified foods, etc. It appears judicious to first screen the chicken genome for possible endogenous products that can confer protection or resistance to H5N1 infection so that further strategies can be developed to exploit them without introduction of exogenous genes.

MicroRNAs (miRNA), that are short, endogenous, noncoding RNAs, regulate a variety of biological processes such as cell growth, tissue differentiation, apoptosis, and viral infection by sequence-specific targeting of mRNAs.5,6 They act at sequence level to regulate gene expression, either by degrading mRNA of target protein or by causing translational repression of target protein by inhibiting mRNA of target protein, thus act as master switches in many biological pathways.7–9

Recently, miR-181 has been identified as a positive regulator of immune response, and miR-181 mimics have been shown to strongly hinder porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication in vitro by specifically binding to a highly (over 96%) conserved region in the downstream of open reading frame (ORF) 4 of the viral genomic RNA.10 miR-181b is reported to inhibit the replication of mink enteritis virus (MEV) in the feline kidney (F18) cell line by targeting the MEV non-structural protein 1 (NS1) mRNA in the coding region.11 The H5N1 genome contains eight segments of negative-sense RNA (13.5 kb) of which the segment 2 encodes three proteins, PB1, PB1-F2, and N40, which are translated from the same mRNA by ribosomal leaky scanning and reinitiation.12 The sequence-specific targeting of this segment can result in the downregulation of three viral proteins and affect the viral replication in host cells. Strategies such as use of candidate miRNAs or the use of the mimics of these miRNAs can be used for providing protection to chicken against avian influenza. The lungs are a major site of replication of H5N1 in chicken.13 In this study, we screened a set of 300 miRNAs expressed in lungs of chicken, with an intent to identify endogenously expressed chicken miRNAs that can potentially target the segment 2 of H5N1.

Materials and Methods

Selection of target sequence

The sequence of segment 2 of influenza A virus H5N1 (A/chicken/India/CA0301/2011(H5N1)) having accession number CY092122 was selected as the target sequence for the study, because this was a complete sequence of segment 2 of H5N1 and had the codon sequence for PB1, PB1-F2, and N40. The whole sequence was retrieved from the NCBI database.

Selection of miRNAs for targeting segment 2 of influenza A virus

A set of 300 miRNA that were identified to be expressed in chicken lungs, by high throughput sequencing (unpublished), were included in the study and screened for presence of target site in the transcript of segment 2 of H5N1.

Filtering of miRNAs for target identification

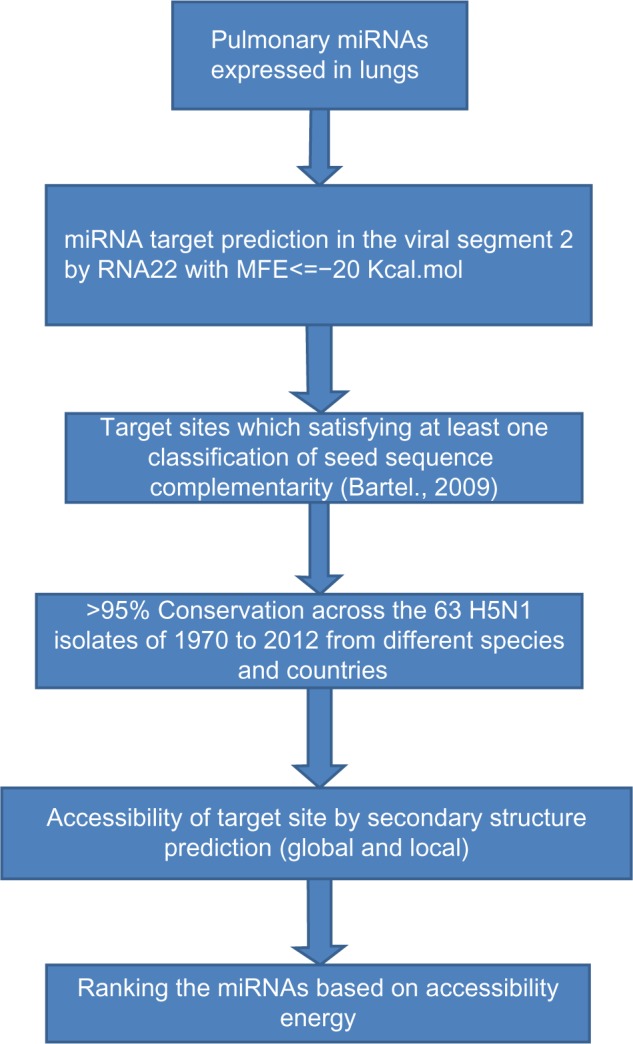

Four successive filters were used to identify chicken miRNAs with potential binding site in segment 2 of H5N1 virus (Fig. 1). The miRNAs were first filtered for the thermodynamic stability of heteroduplex between miRNA and mRNA target site, based on minimum folding energy (MFE). The second criterion used was satisfaction of at least one type of seed sequence complementarity. This was followed by screening for conservation of miRNA target sites across 64 randomly selected H5N1 isolates between 1970 and 2012. Finally, the accessibility of the target sites on the predicted secondary structure of the viral mRNA was also taken into consideration.

Figure 1.

Work flow for the prediction of pulmonary chicken miRNAs that target expression of protein from segment 2 of HPAIV (H5N1).

Identification of miRNAs targets in segment 2 of influenza A virus

In the first step of filtering, RNA22 miRNA target detection algorithm9 (http://cbcsrv.watson.ibm.com/rna22.html) was used for identification of site in target mRNA. Keeping the maximum number of allowed UN-paired bases set to zero in a seed sequence of 6 bases and the minimum number of paired bases in heteroduplex as 14, each individual miRNA was screened for the presence of target sites in the segment 2 of H5N1. Based on the thermodynamics of the miRNA and target-site heteroduplex, all miRNAs with one or more target site in segment 2 of H5N1 with MFE of hybridization < −20 kcal/mol were selected for further screening.

Target sites with seed sequence complementary

miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression is a sequence-specific process. The complementarity of the miRNA seed sequence and the target site are critical for effective targeting. Hence, the target sites of the miRNAs were further filtered for the type of seed sequence complementarity as described by Bartel (2009). Only those that showed at least one of the types of complementarity necessary for effectiveness of miRNA14 were selected for further analysis.

Conservation of target sequence

Avian influenza virus H5N1 is known to undergo antigenic drift and shift due to changes in its gene sequences. In order to be targeted by a chicken miRNA, it is necessary that the target site should lie in the conserved regions of H5N1 genome. A total of 63 complete sequences of segments 2 of H5N1 isolated in 24 different Asian, European, American, and African nations from 1959 to 2012 were included. They were selected so as to include H5N1 isolated from different avian species including chicken, turkey, goose, bean goose, muscovy duck, mallard duck, wild duck pigeon, crow, swan, black-nested grebe, whooper swan, quail, and magpie. The sequences were downloaded and aligned using MEGA5 software. Only those miRNAs whose target sites were conserved across at least 95% of the isolates were selected for further analysis.

Target-site accessibility by RNA folding structure

As a measure to further strengthen the target-site prediction procedure, accessibility of the target site was the next criteria. Accessibility of the target sites was evaluated based on the secondary structure of the target mRNA. The “mfold Web Server” (http://mfold.rna.albany.edu.) was used for RNA folding form with default parameters. Two types of folds, namely the global fold, which was the secondary structure of the complete coding sequence, and the regional fold, which was the secondary structure obtained by folding about 220 bases with 100 bases on either sides of the target site sequence, were included in the study. The presence of at least three unpaired nucleotides in the sequence complimentary to the seed sequence was taken as the filter criteria.

Ranking of predicted miRNA target

The accessibility energy of the identified miRNA targets was used for ranking the miRNAs identified to target the segment 2 of H5N1. The MFE of regional folding with constraint of unpairing at the target site (ΔGunpaired) compared with that of the native fold (ΔGfree) to assess the free energy of unfolding (ΔGopen). The accessibility energy of the miRNA target sites were calculated as: accessibility energy (ΔΔG) = ΔGduplex − ΔGopen, where, ΔGopen = ΔGfree − ΔGunpaired. The miRNA with the lower accessibility energy was ranked best.

Results

Identification of miRNAs targets in segment 2 of influenza A virus

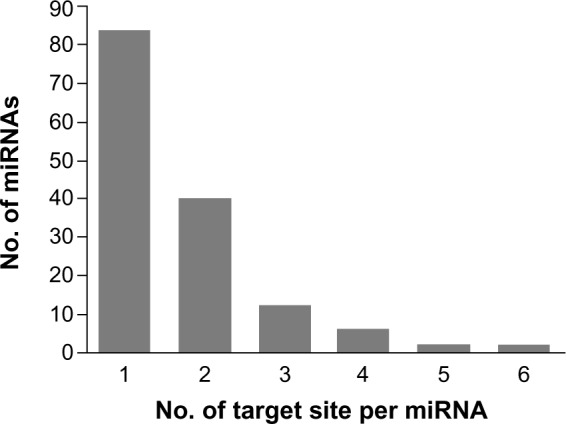

On screening, the 300 miRNAs expressed in the chicken lungs, for target sites in the segment 2 of H5N1 virus, 146 miRNAs showed 253 targets (Supplementary Table 1) in the transcript of segment 2 with MFE of heteroduplex less than −20 kcal/mol. While 84 miRNAs had single target sites, some of the miRNAs had more than one target site and even up to six target sites (Fig. 2). The target sites were identified all along the length of the segment transcript including the 5′-UTR, 3′-UTR, and the Coding sequence (CDS) of the genes coded by the segment.

Figure 2.

Distribution of microRNAs against the number of target sites (MFE ≤ −20 kcal/mol) identified per miRNA in segment 2 of HPAIV (H5N1).

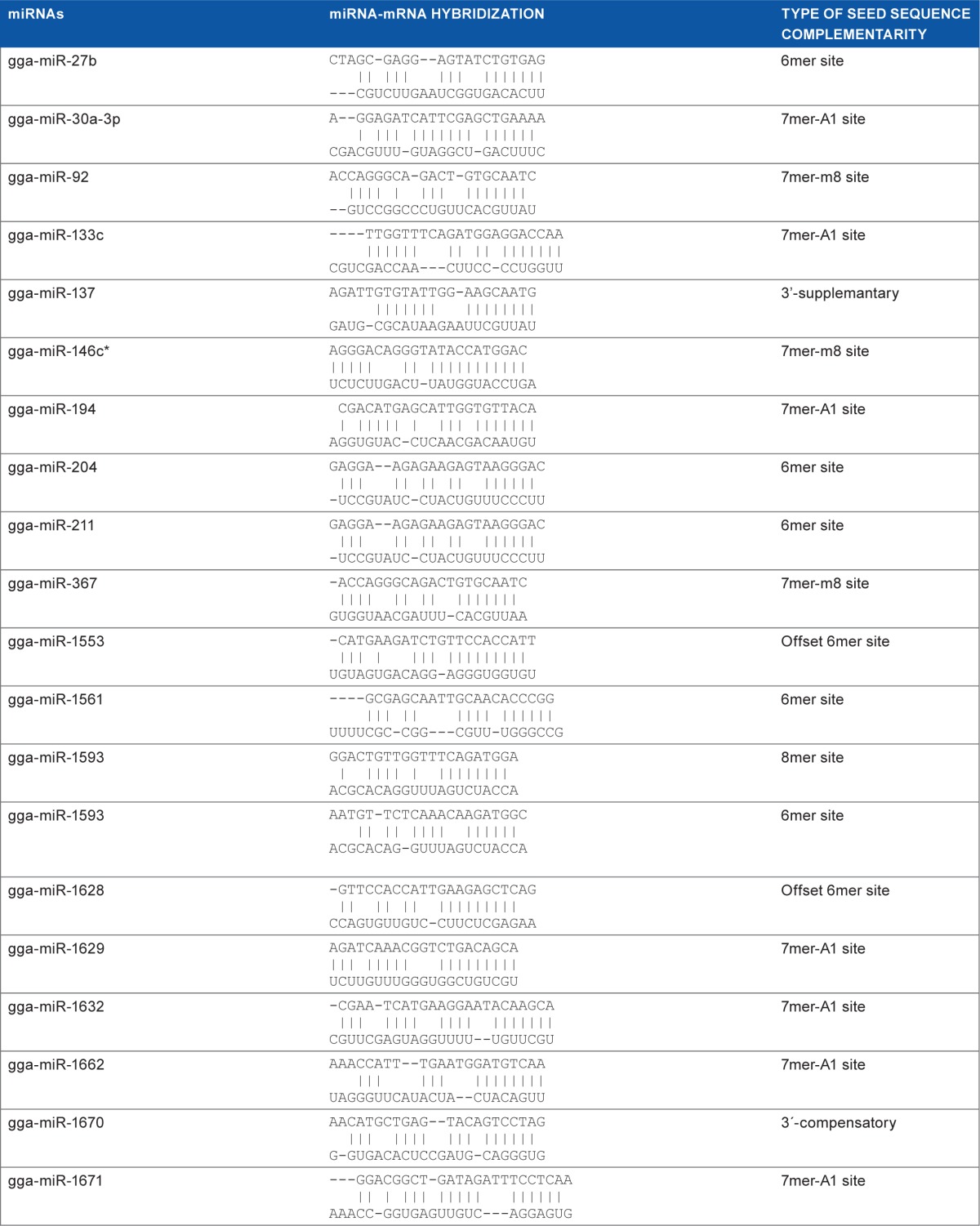

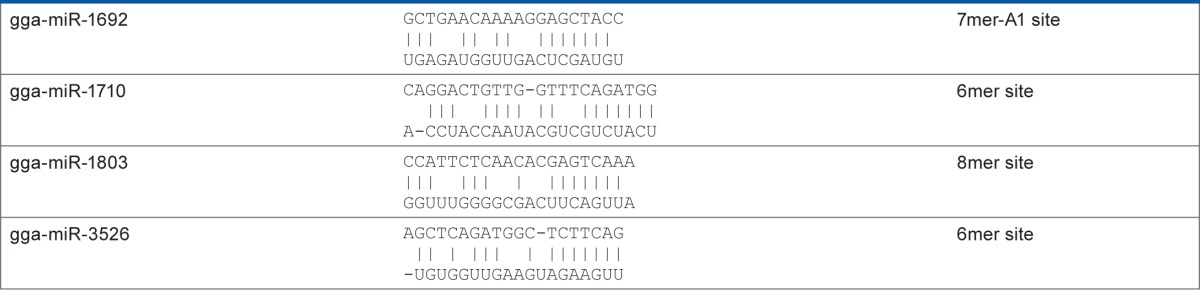

Seed sequence complementarity and conservation of target sites

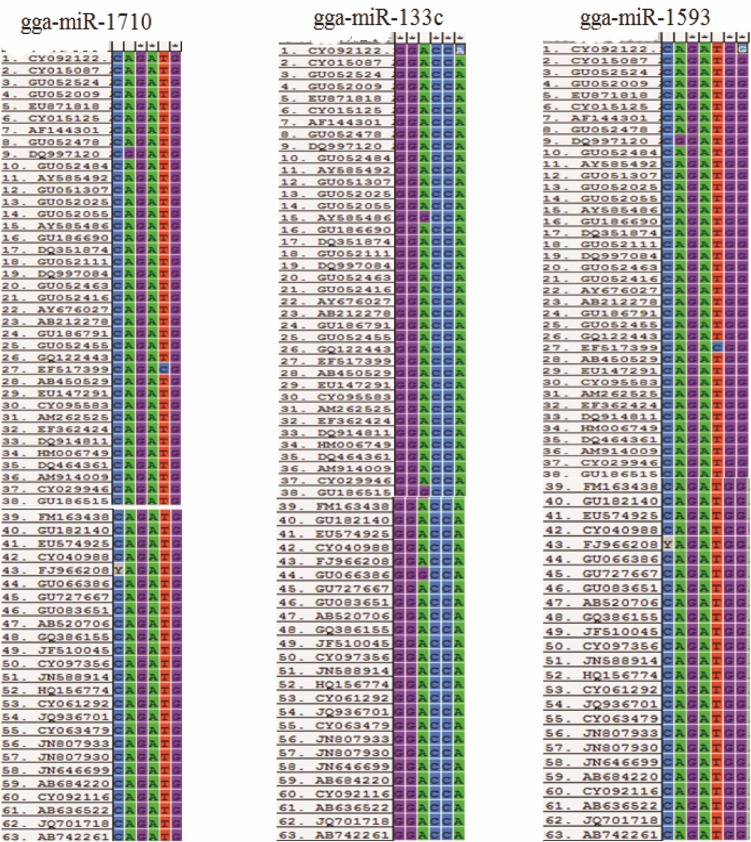

Complementarity between the target site and the seed sequences of the miRNAs have been identified as an important factor for the effectiveness of miRNA-mediated knocking down. On screening, the target-miRNA hybrid predicted by RNA22 was reported for complementarity types.14 Twenty-four miRNAs–mRNA hybrids were found to have target sites with seed sequence complementarity necessary for effective miRNA targeting (Table 1, Supplementary data file). Of these, 11 were found to be conserved across more than 95% of the sequence of segment 2 of the 63 different isolates of H5N1 included for the analysis (Fig. 3, Table 2). The miRNA gga-miR-1593 had two target sites that satisfied the criteria of seed sequence complementarity but only one of them was sufficiently conserved.

Figure 3.

Alignment report complementary site of the seed sequence of miRNAs across segment 2 of 63 H5N1 isolates.

Table 2.

Homology of target site sequence across segment 2 of 63 HPAIV (H5N1) isolates from different avian species in 24 different countries, reported between years 1970 and 2012. ”+” indicates 100% homology of target sequence.

| ACC. NO. | HOST SPECIES | COUNTRY | YEAR | CHICKEN miRNAs (LOCATION OF TARGET SITE WITH REFERENCE TO CY092122) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gga-miR-1671(505 to 527) | gga-miR-3526(1653 to 1671) | gga-miR-1803(2042 to 2062) | gga-miR-1670(1261 to 1282) | gga-miR-1553(2253 to 2274) | gga-miR-1628(2264 to 2285) | gga-miR-1692(657 to 676) | gga-miR-1593(1050 to 1070) | gga-miR-1593(1786 to 1806) | gga-miR-1629(475 to 495) | gga-miR-27b(796 to 816) | gga-miR-30a-3p(1735 to 1756) | gga-miR-92(1883 to 1903) | gga-miR-133c(1792 to 1813) | gga-miR-137(279 to 300) | gga-miR-146c*(126 to 147) | gga-miR-194(1587 to 1608) | gga-miR-204(582 to 603) | gga-miR-211(582 to 603) | gga-miR-367(1883 to 1903) | gga-miR-1561(738 to 758) | gga-miR-1632(1385 to 1407) | gga-miR-1662(14 to 35) | gga-miR-1710(1784 to 1805) | ||||

| CY092122 | Chicken | India | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CY015087 | Chicken | United Kingdom | 1959 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| GU052524 | Chicken | United Kingdom | 1959 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| GU052009 | Mallard | USA | 1975 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| EU871818 | Turkey | Canada | 1983 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| CY015125 | Turkey | United Kingdom | 1991 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| AF144301 | Goose | China | 1996 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| GU052478 | Avian | Italy | 1997 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| DQ997120 | Chicken | China | 1997 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| GU052484 | Duck | Hong Kong | 1998 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| AY585492 | Duck | China | 1999 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| GU052025 | Goose | Hong Kong | 1999 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| AY585486 | Duck | China | 2000 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| GU052055 | Goose | Hong Kong | 2000 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| GU051307 | Mallard | USA | 2000 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| DQ351874 | Chicken | China | 2001 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| GU186690 | Duck | Hong Kong | 2001 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| GU052111 | Goose | Viet Nam | 2001 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| DQ997084 | Chicken | China | 2002 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| GU052463 | Goose | Hong Kong | 2002 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| GU052416 | Chicken | Indonesia | 2003 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| AY676027 | Chicken | South Korea | 2003 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| AB212278 | Duck | Japan | 2003 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| GQ122443 | Chicken | Indonesia | 2004 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| GU052455 | Magpie | South Korea | 2004 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| GU186791 | Wild Duck | USA | 2004 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| EU147291 | Avian | Russia | 2005 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| CY095583 | Mallard | Italy | 2005 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| EF517399 | Mallard | Canada | 2005 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| AB450529 | Pigeon | Thailand | 2005 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| DQ914811 | Chicken | China | 2006 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| DQ464361 | Swan | Germany | 2006 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| EF362424 | Chicken | India | 2006 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| HM006749 | Chicken | Laos | 2006 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| AM262525 | Chicken | Nigeria | 2006 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| GU182140 | Chicken | China | 2007 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| AM914009 | Bl.nest-ed Grebe | Germany | 2007 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| FM163438 | Chicken | Poland | 2007 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| GU186515 | Turkey | USA | 2007 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| CY029946 | Chicken | Kuwait | 2007 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| GU727667 | Duck | China | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| GU066386 | Chicken | India | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| EU574925 | Chicken | Israel | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| FJ966208 | Crow | India | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| CY040988 | Chicken | Laos | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| GQ386155 | Bean Goose | Russia | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| JN588914 | Chicken | Combodia | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| GU083651 | Chicken | India | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| CY097356 | Mallard | USA | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| AB520706 | Whoop-er Swan | Mangolia | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| JF510045 | Wild Duck | South Korea | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| CY063479 | Chicken | Bhutan | 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| CY061292 | Chicken | India | 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| HQ156774 | Chicken | Bangladesh | 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| JQ936701 | Chicken | Myanmar | 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| JN807933 | Duck | South Korea | 2010 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| AB684220 | Chicken | Japan | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| CY092116 | Chicken | India | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| JQ701718 | Duck | Combodia | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| JN646699 | Duck | China | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| AB636522 | Muscovy Duck | Viet Nam | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| JN807930 | Quail | South Korea | 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| AB742261 | Duck | Viet Nam | 2012 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

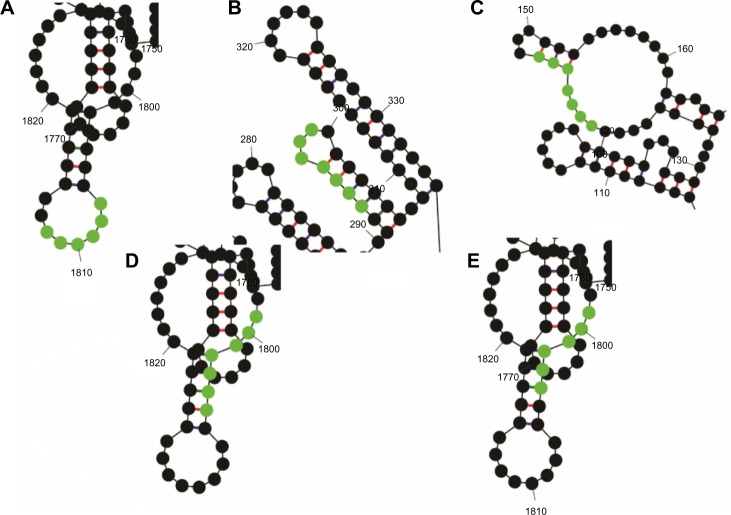

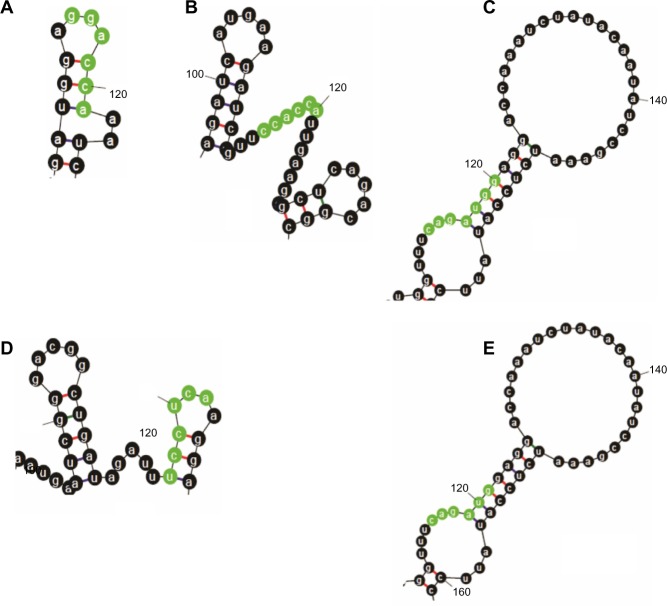

Target site accessibility

The miRNAs gga-miR-133c, gga-miR-137, gga-miR-146c*, gga-miR-1593, and gga-miR-1710 had accessible targets on transcript-based global folding structures (Fig. 4), while gga-miR-133c, gga-miR-1553, gga-miR-1593, gga-miR-1671, and gga-miR-1710 show accessibility to target site based on the regional folding (Fig. 5). Those miRNAs that show accessibility to the target site by both folding methods may be assumed to have higher probability of being effective in down regulation of the target proteins as the secondary structure of RNA is a dynamic one in a live cell.

Figure 4.

MicroRNA target sites of (A) miR-133c, (B) miR-137, (C)miR-146c*, (d)miR-1593, and (e) miR-1710, highlighted from the secondary structure of mRNA from segment 2 of H5N1 in global folding.

Figure 5.

MicroRNA target sites of (A) miR-133c, (B) miR-1553, (C) miR-1593, (d) miR-1671 and (e) miR-1710, highlighted from the secondary structure of mRNA from segment 2 of H5N1 in regional folding. The regional folding was obtained by inclusion of 10 bases on either side of the target sequence for secondary structure prediction.

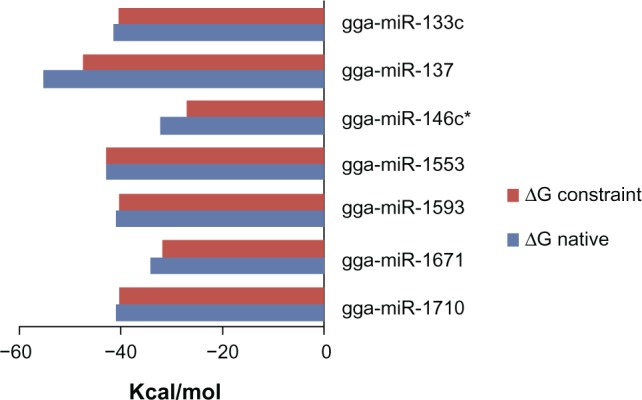

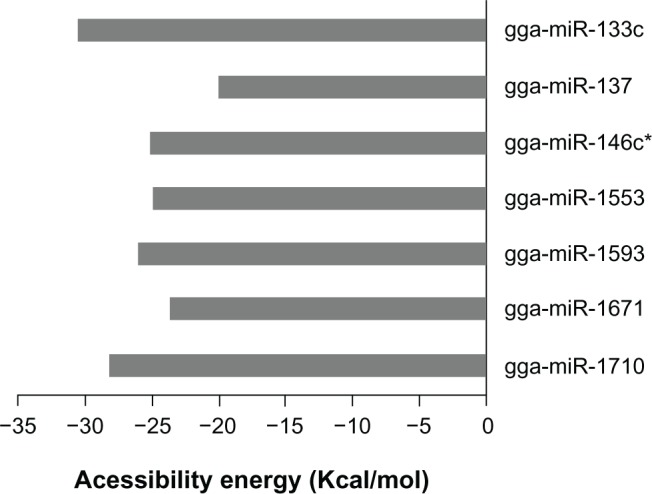

Ranking of miRNAs by accessibility energy

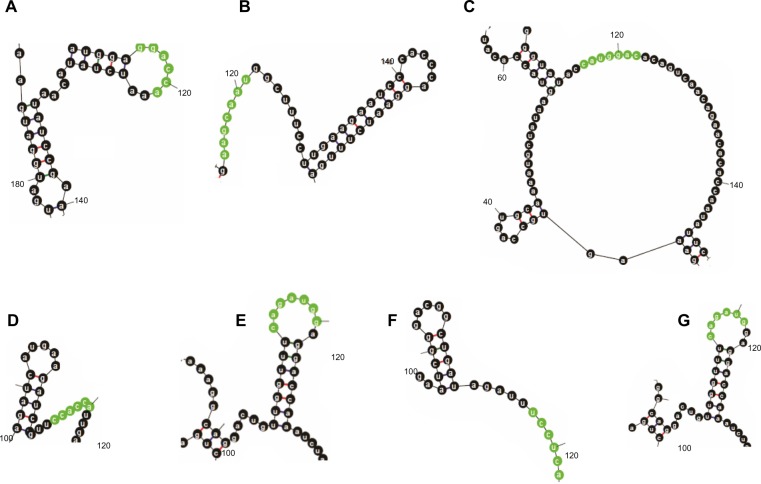

The accessibility energy is an indicator of the thermodynamic feasibility of the process of miRNA–mRNA hybridization while the former is in its secondary structure. Hence, this is a suitable parameter to rank the effectiveness of the predicted miRNAs (Fig. 5). The basis here is the difference between the MFE of native folding and the MFE of folding, such that the base pairing at the seed sequence complementary site is inhibited (Figs. 6 and 7). On ranking the miRNAs based on the accessibility energy, gga-mir-133c was found to be the best followed by gga-mir-1710 and gga-mir-146c* (Fig. 8). Of these, the first two also show accessibility to target site both on global folding and regional folding. Those miRNA that show accessibility to the target site by both folding methods may be assumed to have higher probability of being effective in down regulation of the target proteins as the secondary structure of RNA is a dynamic one in a live cell.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the MFE value (ΔG) of native secondary structure and secondary structure with a constraint to prohibit base pairing at the miRNA target site.

Figure 7.

MicroRNA target sites of (A) miR-133c, (B) miR-137, (C) miR-146c*, (d) miR-1553, (e) miR-1593, (F) miR-1671, and (G) miR-1710, highlighted from the secondary structure of mRNA from segment 2 of H5N1 in regional folding with a constraint to prohibit base pairing at the target site.

Figure 8.

Accessibility energy of miRNAs target site on the mRNA from segment 2 of H5N1.

Discussions

The segment 2 of HPAI (H5N1) encodes proteins PB1, PB1-F2, and N40, which contribute significantly to host and virus interaction. PB1, the core component of the viral polymerase, has been linked to inter-strain differences in pathogenicity and host range.15,16 PB1-F2 is an alternative translation product of the viral PB1 segment which is a pro-apoptotic mitochondrial viral pathogenicity factor.17 Expression of full-length PB1-F2 increases the pathogenesis of the influenza A virus, causing slower viral clearance and increased viral titers in the lungs.18 It is assumed to be an important contributor to pathogenicity of pandemic influenza viruses.19 N40 represents an N-terminally deleted form of PB1 and lacks transcriptase function but interacts with PB2 and the polymerase complex in the cellular environment.20 The deletion of N40 is reported to result in the attenuation of the virus possibly due to the simultaneous change in the PB1 sequence.12 All this makes the segment 2 of H5N1 suitable for sequence-specific targeting studies.

The first criteria for target identification as free energy below −20 kcal/mol for miRNA-target hybridization were based on reports of similar target prediction studies with reference to influenza virus. Some researchers have used a cutoff free energy of −17 kcal/mol for predicting miRNA targets in PB1 gene of H1 N121 and some have used a threshold free energy of −15 kcal/mol while predicting the binding site of miRNA to NS1 gene of H1 N1 and H5N1.33 The complete length of segment 2 was screened for target sites of the miRNAs as three different proteins were expressed from the same segment and the same target site may have a different impact on the different proteins. Although most investigation into metazoan miRNA function has been for sites in 3′-UTRs, experiments using artificial sites show that targeting can occur in 5′-UTRs and open ORFs.22,23 The mRNA and protein expression of genes containing target sites both in coding regions and 3′-UTRs are reported to be mildly but significantly more regulated than those containing target sites in 3′-UTRs only.24

Seed sequence complementarity is critical for effective miRNA targeting. Although perfect complementarity is not necessary for effective silencing of expression in animal, specific pattern of seed sequence complementarity have been reported to be effective on the basis of experimentation and prediction.12 Hence, the target sites predicted by the RNA22 were analyzed to classify them as per seed sequence complementarities. AIV is known to show genetic drift before an miRNA can be identified to target its gene, it was important that it should be conserved. Also change in the sequence at the target site would alter the thermodynamics of hybridization as well as seed sequence complementarity thus affecting the effectiveness. It is conventional to screen for conservation of the target site in majority of target-prediction databases like TargetScan, miRanda, etc. This filter was also necessary as the purpose of the study was to identify genetic components of chicken genome that can target the viral gene expression, and unless the target site is conserved, there would not be consistence in results.

The targets identified by our approach were not predicted by the ViTa database, which predicts targets of host miRNAs in viral genes.25 This might be due to the fact that the target identification tools in its pipeline is miRanda26 and TargetScan,27 while we have used RNA22 here. Although miRranda is an efficient tool, it underestimates miRNAs with single but perfect base pairing as against those with multiple target sites. On the other hand, TargetScan identifies only those sites that are conserved across several species. Conservation across several species was not an important factor here, as the rationale of this study was data mining of chicken miRNAs only for the presence of genetic factors in chicken, if any, which can potentially affect the expression of critical H5N1 genes.

Accessibility is an important factor for targeted downregulation by miRNA. Long et al (2007) suggested that the presence of at least four consecutive nucleotides complementary to any part of miRNA in unpaired state in secondary structure of target RNA is required for initiation of the binding process between the target and the miRNA.28 Robin et al (2005) proposed screening based on the presence of only three consecutive nucleotides complementary to the seed sequence as unpaired.29 Here, the presence of only three consecutive unpaired nucleotides complementarity to the seed sequence was used as filter criteria to improve precision of the target prediction, because this gives due importance to the seed sequence complementarity while screening for the unpaired stretches in the secondary structure of target sequence. The folding algorithm cannot warranty the reliable structures of long sequences.30 The protein involved in the recognition of RNA strand are expected to hinder the formation of long-range interactions, thus making target accessibility a matter of local secondary structure.31 However, the predicted local folding may also not represent the exact secondary structure of an RNA molecule. Hence, for the study, global as well as regional folding of the mRNA was considered.

Conclusion

The chicken genome has miRNAs that can potentially target the expression of the genes expressed from the segment 2 of H5N1 virus. The position of target of gga-miR-133c on segment 2 transcript is 1792–1813. Hence, it can target the PB1 and N40 protein by binding in their coding region and PB1-F2 by binding at 3′-UTR. The gga-miR-146c* targets position 126–147 and hence can inhibit PB1 and PB1-F2 at the coding regions and N40 at the 5′-UTR. This indicates that these host miRNAs have potential for regulating the expression of multiple viral proteins namely, PB1, PB1-F2, and N40. Since these miRNA are being expressed in the chicken lungs, they may be useful for inhibition of H5N1 replication or the development of resistance against H5N1 infection in chicken. However, the miRNAs identified to target genes of segment 2 are targeting the different proteins at different location with reference to their ORF; hence, they might have variable extent of impact on the regulation of these gene expressions. Those miRNAs that show accessibility to the target site by both folding methods may be assumed to have higher probability of being effective in down regulation of the target proteins as the secondary structure of RNA is a dynamic one in a live cell.

Owing to the fact that miRNAs are pleiotropic in their effect, these shortlisted miRNAs may have other off-target effects as well. Several databases like the miRDB32 or TargetScan.27 provide list of target genes for each of these miRNAs in chicken, but they bioinformatically predicted based on orthology and other parameters. Here, the effective impact of the miRNAs on these predicted host gene targets cannot be compared with their inhibitory impact on segment 2 genes of H5N1 as the pipeline for prediction are different. Hence, the biological usefulness and effectiveness of these miRNAs for the inhibition of H5N1 replication in chicken needs to be evaluated further by biological experimentations such as in vitro virus challenge and luciferase reporter assays, etc. However, the bioinformatics approach of this study has aided in narrowing down on three miRNAs for targeting the segment 2 of H5N1, from the given 300 miRNAs expressed in chicken lungs. This approach of in silico screening and short listing, before taking up biological experimentation, would save enormous resources that go into the conducting of wet laboratory experiments especially in the case of H5N1, which is a BSL3 agent.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary File 1. List of target site identified by RNA22 with MFE ≤ −20 kcal/mol.

Supplementary File 2. RNA22 output data of miRNA–mRNA hybridization.

Table 1.

MicroRNAs with seed sequence complementarity necessary for effective mRNA targeting.

|

|

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AM, AK. Analyzed the data: AM. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: AK. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: AM, AAR. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: AK, MAVN, AM, AAR, RS, AM. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: AK, MAVN, AM, AAR. Made critical revisions and approved final version: AM. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: JT Efird, Associate Editor

FUNDING: The authors thank Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for financial assistance in the form of a Junior Research Fellowship during the course of this work.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

This paper was subject to independent, expert peer review by a minimum of two blind peer reviewers. All editorial decisions were made by the independent academic editor. All authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including (but not limited to) use of any copyrighted material, compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests disclosure guidelines and, where applicable, compliance with legal and ethical guidelines on human and animal research participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander DJ. A review of avian influenza in different bird species. Vet Microbiol. 2000;74:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OIE . Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (Mammals, Birds, and Bees) 5th ed. Paris, France: OIE; 2004. pp. 258–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebmann T, Zelicoff A. Vaccination against influenza: role and limitations in pandemic intervention plans. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(8):1009–19. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Use of antiviral drugs in poultry, a threat to their effectiveness for the treatment of human avian influenza. 2005. Available at http://www.who.int/foodsafety/micro/avian_antiviral/en/

- 5.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miska EA. How microRNAs control cell division, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:563–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–73. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo X, Zhang Q, Gao L, Li N, Chen X, Fenga W. Increasing expression of microRNA 181 inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication and has implications for controlling virus infection. J Virol. 2013;87(2):1159. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02386-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun JZ, Wang J, Yuan D, et al. Cellular microRNA miR-181b inhibits replication of mink enteritis virus by repression of non-structural protein 1 translation. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tauber S, Ligertwood Y, Quigg-Nicol M, Dutia BM, Elliott RM. Behaviour of influenza A viruses differentially expressing segment 2 gene products in vitro and in vivo. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:840–9. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.039966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chamnanpood C, Sanguansermsri D, Pongcharoen S, Sanguansermsri P. Detection of distribution of avian influenza H5N1 virus by immunohistochemistry, chromogenic in situ hybridization and real-time PCR techniques in experimentally infected chickens. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42(2):303–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartal DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taubenberger JK, Kash JC. Influenza virus evolution, host adaptation, and pandemic formation. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:440–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naffakh N, Tomoiu A, Rameix-Welti MA, van der Werf S. Host restriction of avian influenza viruses at the level of the ribonucleoproteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:403–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmolke M, Manicassamy B, Pena L, et al. Differential contribution of PB1-F2 to the virulence of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus in mammalian and avian species. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(8):e1002186. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conenello GM, Zamarin D, Perrone LA, Tumpey T, Palese P. A single mutation in the PB1-F2 of H5N1 (HK/97) and 1918 influenza A viruses contributes to increased virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(10):e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamarin D, Ortigoza MB, Palese P. Influenza A virus PB1-F2 protein contributes to viral pathogenesis in mice. J Virol. 2006;80:7976–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00415-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wise HM, Foeglein A, Sun J, et al. A complicated message: identification of a novel PB1-related protein translated from influenza A virus segment 2 mRNA. J Virol. 2009;83:8021–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00826-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song L, Liu H, Gao S, Jiang W, Huang W. Cellular microRNAs inhibit replication of the H1 N1 influenza A virus in infected cells. J Virol. 2010;84(17):8849–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00456-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloosterman WP, Wienholds E, Ketting RF, Plasterk RH. Substrate requirements for let-7 function in the developing zebrafish embryo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6284–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA. Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5′ UTR as in the 3′UTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9667–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang Z, Rajewsky N. The impact of miRNA target sites in coding sequences and in 3′UTRs. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu PW, Lin LZ, Hsu SD, Hsu JB, Huang HD. ViTa: prediction of host microRNAs targets on viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D381–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enright A, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks D. MicroRNA targets in. Drosophila Genome Biol. 2003;5(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long D, Lee R, Williams P, Chan CY, Ambros V, Ding Y. Potent effect of target structure on microRNA function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:287–94. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robins H, Li Y, Padgett RW. Incorporating structure to predict microRNA targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(11):4006–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500775102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doshi K, Cannone J, Cobaugh C, Gutell R. Evaluation of the suitability of free-energy minimization using nearest-neighbor energy parameters for RNA secondary structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tafer H, Ameres SL, Obernosterer G, et al. The impact of target site accessibility on the design of effective siRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:578–83. doi: 10.1038/nbt1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X. miRDB: a microRNA target prediction and functional annotation database with a wiki interface. RNA. 2008;14(6):1012–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.965408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koparde P, Singh S. Prediction of micro RNAs against H5N1 and H1 N1 NS1 protein: a window to sequence specific therapeutic development. J Data Mining Genomics Proteomics. 2010;1:2–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1. List of target site identified by RNA22 with MFE ≤ −20 kcal/mol.

Supplementary File 2. RNA22 output data of miRNA–mRNA hybridization.